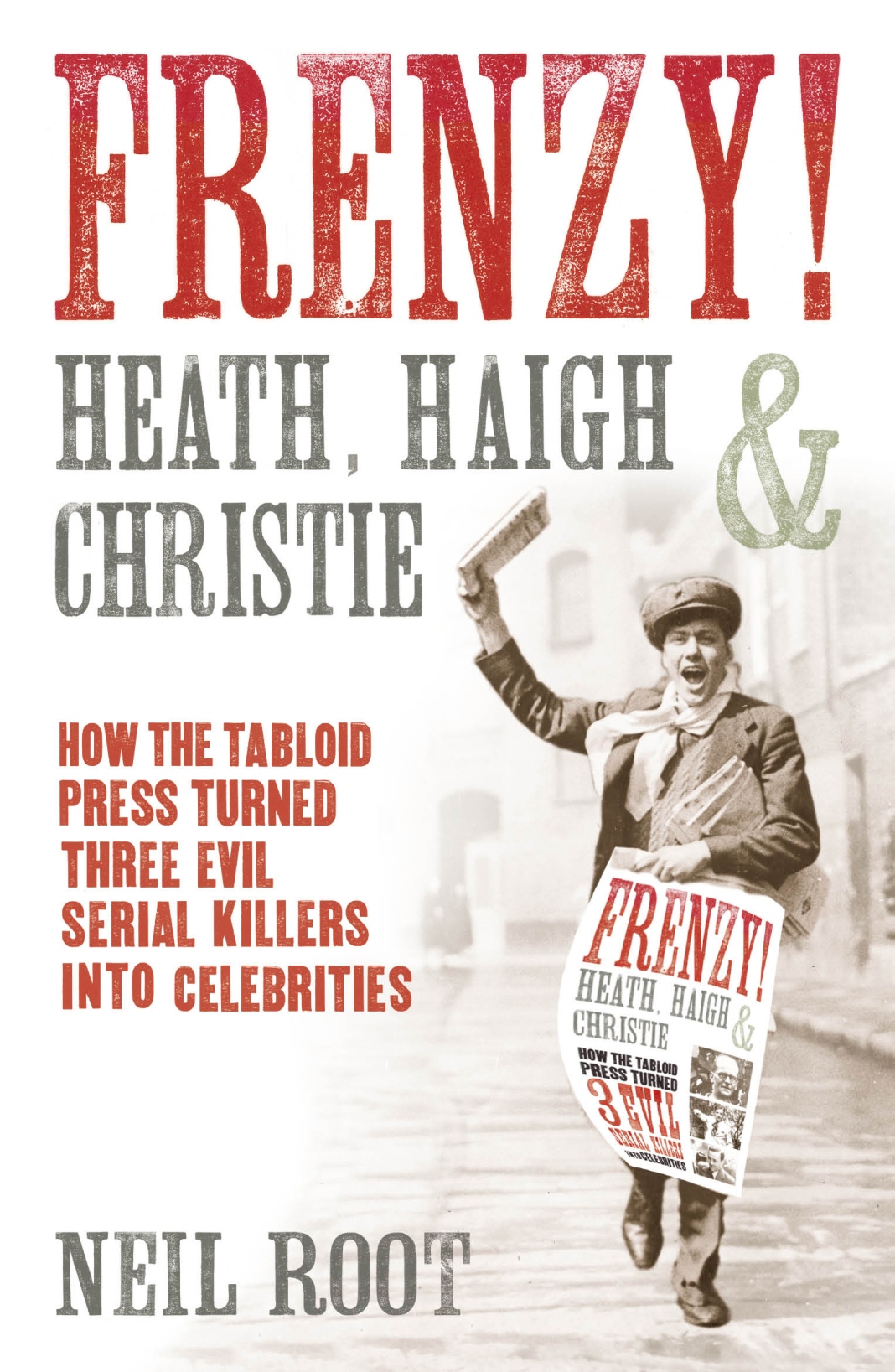

Murder has transfixed the popular press for centuries. But it was in the second half of the twentieth century that murder began saturating front pages and making these monsters what we today recognise as ‘modern celebrities’.

It was three serial killers, caught and executed in the few years after the end of the Second World War, who precipitated a level of furore never seen before. Neville Heath, a ‘charming’ sadist who killed two women; John George Haigh, the ‘Acid Bath Killer’ who killed between six and nine men and women; and John Christie, the ineffectual necrophile, who killed between six and eight women.

The modern news coverage finds its roots with these three men whom the crime historian Donald Thomas called the ‘Postwar Psychopaths’. Their crimes were the first to generate a tabloid frenzy the like of which we see all around us today. It was not only the murderers who captured the public’s imagination. It was the detectives who hunted them down, the judiciary who tried them, and the man who executed them, the legendary hangman Albert Pierrepoint.

This book tells the stories of these three infamous serial killers against the backdrop of the tabloid frenzy that surrounded them.

Neil Root was born in London in 1971. He is a graduate of the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Manchester. As well as being a writer, he is a lecturer and teacher in English Literature and Language. He has worked abroad in several countries. He has a special interest in true crime, psychology and history, and has read and researched widely on these subjects. He lives in London.

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Postscript

Bibliography

Index

Copyright

IN THE TWENTY-FIRST century the society in which we live is a twenty-four-hour television news and Internet culture. Breaking news is on air and online within hours, sometimes minutes or even seconds. This is especially true when it comes to murder cases, the dark and sensational details of the extraordinary actions and sad misfortunes of others keeping viewers and surfers gripped. This has in turn put pressure on the tabloid press, its readership drifting away to the new media. Pages and pages in newspapers are devoted to gruesome events and tales, sometimes with a level of detail that is truly chilling. Just how did we get to this incredible level and detail of murder coverage?

Murder has transfixed the popular press since the mid-nineteenth century, a statement which says a lot about human nature and society, as tabloids mirror their readership. Editors know what people want and deliver it, week in and week out. Murder is the rarest form of crime and yet it gets far more coverage than any other. Why is this? The answer must be because the public wants to read about it. In the second half of the twentieth century murder saturated front pages as never before. Three British serial killers caught and executed in the few years after the end of the Second World War provoked a level of coverage never seen before, the precursor to the press frenzies which surround serial murder today. Neville Heath, a ‘charming’ sadist who killed two women; John George Haigh, the acid bath killer, who killed between six and nine men and women; and John Christie, the ineffectual necrophile who killed between six and eight women – modern news coverage was born with the stories of these three men who crime historian Donald Thomas called the ‘post-war psychopaths’.

Post-war London was a bleak and ravaged city, blitzed and scarred by German bombs. The chaos and savagery of war had desensitised people and in many ways cheapened human life. The population of cities all over Britain but particularly London had seen and experienced terrible things. Almost everybody had lost a loved one.

In the midst of this devastation, the underworld thrived and the crime rate shot up. As Colin Wilson points out in A Criminal History of Mankind, in 1946 crime was at twice the level of 1939, a doubling of robberies, burglaries, rapes and crimes of violence. Although in 1954 overall crime was lower than in 1945, only robbery and burglary had fallen sharply, due to greater affluence. Violent offences and sex crimes had doubled again since the end of the war.

Between 1946 and 1953 serial killers Neville Heath, John George Haigh and John Christie became the macabre pin-ups of their age and set the tone for the news frenzy which surrounds multiple or gruesome murders today. Heath mutilated and murdered two young women with a brutal ferocity not seen in Britain since Jack the Ripper, with the possibility of a further victim. Haigh killed between six and nine men and women for financial gain, dismembering and dissolving them in acid baths, and perhaps drinking blood from their necks. Christie strangled between six and eight women, performing necrophilia on their bodies and burying them in his garden or under the floorboards, or storing them in a kitchen cupboard.

The police files on Neville Heath (closed extract: 260 pages and fourteen photographs) have never been declassified. This author made a Freedom of Information request for the files in November 2010, but after long consideration it was decided by the Freedom of Information assessor that they could not be released to the public. This is because of an exemption clause to access. To quote the assessor, ‘This exemption applies to information in the extract that relates to an unconnected murder that remains unsolved, and this information may be used to reinvestigate this case in the future.’ This tells us that Neville Heath was a strong suspect for a further murder during the police investigation of June–July 1946, something which has not until now been known. We may never know if indeed Heath did claim a third victim, but this tells us that it is possible.

The crimes and lives of these murderers have been documented before. The most recent biography of Neville Heath was published in 1988, the last of John George Haigh in the 1950s, although he was the subject of the 2002 television drama A is for Acid. John Christie is by far the most notorious, largely because of the miscarriage of justice which resulted in the execution of his upstairs neighbour Timothy Evans in 1950 for the murder of his wife and baby. Ludovic Kennedy’s 1961 book Ten Rillington Place is the definitive work on Christie and Evans, and updated editions were produced. However, under the Freedom of Information Act, more information has been obtained from the archives, details that shine new light on the extraordinary crimes of Heath, Haigh and Christie. All of this material is included in this book and helps us get closer to the truth.

An angle that Ludovic Kennedy did not cover on the Christie–Evans case was the effect of the massive media interest at the time on the charging, conviction and execution of Timothy Evans. The pressure on the police and judiciary meant that Evans was not given a fair trial. The proof of this is that Ludovic Kennedy’s book, which was prefaced by an open letter to the Home Secretary of the day, gained Evans a posthumous pardon in 1966. The contribution of tabloid news coverage to this infamous miscarriage of justice will also be explored here.

Heath, Haigh and Christie (and Evans) were not the only names to emerge from this darkness. Albert Pierrepoint, Britain’s number-one executioner, hanged all four of these men, and no exploration of the role of the tabloids would be complete without him. As the popular newspapers warmed to their newfound ability to scandalise and sensationalise, he himself became a celebrity. Executioners were required to be discreet and to conduct themselves in a respectful manner and above all avoid any contact with the press. However, when Pierrepoint retired in 1956 over what he regarded as unpaid fees, he went to Empire News and the Sunday Chronicle, who paid him in excess of five hundred thousand pounds in today’s money for a series of sordid stories called The Hangman’s Own Story. In 1974 Pierrepoint published his autobiography in book form.

Tabloids were also directly involved in payments to Heath, Haigh and Christie. The Sunday Pictorial (later the Sunday Mirror) paid huge sums for the inside stories of both Neville Heath in 1946 (although the Daily Mail got the initial story) and John Christie in 1953, and paid their legal costs. The News of the World did the same for John George Haigh in 1949. Incredibly, it was the News of the World that got the full confession from Haigh, not the police. As a direct result of the cavalier and intemperate press coverage of the murders, laws governing the payment of the legal fees of victims and criminals, the withholding of evidence and many other aspects of how the media cover such crimes were changed.

The tabloid journalists of the 1940s and ’50s are an intrinsic part of this story. Crime correspondents had a minor celebrity of their own in the days when the tough crime novels of Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane were flying out of bookshops. In the famous Picture Post magazine in 1947 there was a photographic feature on ‘Fleet Street’s Murder Gang’, accompanied by a photograph of the legendary News of the World crime correspondent Norman Rae. The photograph shows him with his ear to an old-fashioned telephone ‘phoning in his latest scoop’. Rae is part of this story. It is a little-known fact that he arranged to meet Christie without the knowledge of the police while the killer was on the run.

In the end Rae missed his scoop: Christie’s story was ghostwritten for the Sunday Pictorial in 1953 by the equally legendary Harry Procter, who had also got the scoop on Neville Heath in 1946 for the Daily Mail. Incredibly, Procter had actually met Heath twice before his first murder, but it was the Sunday Pictorial which got the full inside story from Heath’s mouth from his death cell, the paper which Procter would move to in the 1950s. Rae was responsible for the ‘confessional’ story of John George Haigh in 1949, and he was the source of many other crime scoops in a long career. Rae and Procter did more than anybody else to stir up the tabloid frenzy around Heath, Haigh and Christie, with the authority of their editors and the expense accounts of their newspapers behind them. Harry Procter would later write his memoirs about his career in Fleet Street entitled The Street of Disillusion. The title says it all. The roles played by members of Fleet Street’s Murder Gang are a key strand of this tale.

Other members of the Murder Gang in this period included Hugh Brady of the Daily Mail, who died in 1949; Charles Leach of the Exchange Telegraph Co.; Jimmy Reid of the Sunday Dispatch; Cecil Catling of the Star; Victor Toddington of the Evening Standard; E. V. Tullet of the Sunday Express; Fred Redman of the Sunday Pictorial; Percy Hoskins of the Daily Express; Gerald Byrne of Empire News (who wrote books on Heath and Haigh soon after they were executed); Reginald Foster of the News Chronicle; Sam Jackett of the Evening News; William Ashenden of the Daily Graphic; Stanley Bishop of the Daily Herald; W. G. Finch of the Press Association; Arthur Tietjen of the Daily Mail; and Harold Whittall of the Daily Mirror. But it is Norman ‘Jock’ Rae and Harry Procter who concern us here.

This was the first time killers had been paid for their stories while in custody, the money going to their families after they were hanged. This was especially important to John George Haigh, who was very close to his mother and wanted to give her a substantial amount of money to improve her life. Never before had the public been exposed to so much sensational information about serial murder. The more the tabloids printed, the more the public lapped it up. The more horrible the better. It was the dawn of a new age. Ludovic Kennedy wrote in Ten Rillington Place, ‘Christie was in the papers every day eclipsing in interest even the death of Queen Mary.’ Heath, Haigh and Christie cultivated their notoriety and basked in their fame. Heath made prodigious efforts to look his best at his trial; Haigh thrived on his perverse celebrity and vampire revelations, and contemporary photographs show him smiling and waving at the crowds outside various courts; and Christie boasted about his murder count being higher than Haigh’s.

The coverage of these three psychopaths and their crimes was the true beginning of contemporary tabloid murder reporting. It was also the birth of the serial murderer as criminal celebrity in Britain. Whipped into a frenzy of excitement by the newspapers, women in particular crowded to catch glimpses of these dangerous men, many fainting at the sight of them in court. This book tells the stories of these serial killers against the backdrop of the tabloid frenzy that surrounded them.

A MAN SITS in the front passenger seat of a Ford Anglia E494A motor car directly outside Wood Green town hall in north-east London. He is built for comfort rather than speed, wearing a heavy black overcoat over his crumpled double-breasted suit, the white display handkerchief in his left breast pocket obscured. His hat has a lighter band sitting above the rim encircling the black felt, covering his closely cropped grey hair and balding pate. If this were a cartoon, the man would have a ‘Press’ sign tucked into his hatband, but this is very much real life. Next to him is a driver, assigned to him by his newspaper. Few hacks have a personal driver, and this shows he is something special.

It’s wet and windy in the after-midnight darkness on the High Road. The town hall looming above the car, an imposing building partially revealed by the street lights, was originally a private residence known as Earlham Grove House with grounds covering twenty-eight acres. The man is sweating, and not just because of his heavy clothes. He is anxious: he is taking a huge risk.

It’s possible a passer-by might recognise the man if he were not sitting slouched in his seat and they could see his face, but the streets are almost deserted. Six years earlier a photograph of him had appeared in the Picture Post, showing him placing a telephone call in a betting office, the sign above his head reading ‘BETTING, WRITING OR PASSING SLIPS STRICTLY PROHIBITED’. The caption of the picture read, ‘Fleet Street crime reporter Norman Rae of News of the World phones the news desk with the latest scoop.’ The article entitled ‘Fleet Street’s Murder Gang’ had appeared on 17 May 1947. But if nobody recognises Norman Rae tonight, most will be familiar with his name. The News of the World has a circulation of eight million a week and, as now, is only published on Sundays. Rae is the paper’s chief crime correspondent.

Norman Rae is a living legend in Fleet Street. Born in Aberdeen in 1896, he is a no-nonsense gruff Scot. He joined the News of the World in the early 1930s, after lying about his age to serve in the Highland Division in the First World War. Since then he has built a reputation as the crime reporter in Fleet Street, a man who can sniff out and secure the most sensational murder stories. An earlier break was getting the inside story on Dr Buck Ruxton in 1936, an Indian doctor practising in Lancashire who killed his wife in a jealous rage and murdered their housemaid because she witnessed the crime. Ruxton then dismembered the bodies, packed the parts into parcels and threw them randomly from a train travelling through Scotland. He was caught because the newspaper he had wrapped the body parts in included a supplement only published in a small part of Lancashire. Rae met Ruxton several times and got the inside scoop, making his name. Since then many other exclusives have followed, the most memorable being the full story of acid bath killer John George Haigh in 1949.

Rae is now fifty-six years old and a veteran of tabloid murder. It is almost 1.30 a.m., and his Ford Anglia, a two-door black saloon, is filling up with the pungent smell and whirling smoke of Rae’s Player’s cigarette and his driver’s Craven A. As the windows are closed against the heavy rain outside, visibility is not good from the car. It’s almost the time of the rendezvous. Rae has arranged to meet John Reginald Halliday Christie, who has been on the run from the police for seven days, since the trussed-up bodies of three women were discovered in a papered-over alcove in his kitchen at 10 Rillington Place in Notting Hill, west London. Christie has been staying in a fleapit hostel in King’s Cross, wandering aimlessly through the smoggy city by day.

Three years earlier his upstairs neighbour Timothy Evans was hanged for the murder of his wife Beryl and baby Geraldine. Christie will later confess to murdering Beryl, and it is highly probable that he killed Geraldine too. Norman Rae covered the arrest, trial and execution of Evans for the News of the World, and Christie kept newspaper cuttings of his work. The previous day – in fact, just two hours ago at 11.20 p.m. – Christie had telephoned the newspaper from a public phone box and asked for Rae. Christie was out of money, cold, wet and hungry, and wanted to sell his story in return for a hot meal. Rae agreed, as long as Christie undertook to surrender himself to the police immediately afterwards. Rae knows the huge risks he is taking in meeting Christie. There is a huge manhunt on for the serial killer and all the papers are following it. But Rae’s bloodhound instinct for a big scoop overrides any moral qualms he may have had.

It’s now 1.30. Rae nods to his driver, steps out of the car and braves the rain on the pavement. Just then and purely coincidentally, a policeman on the beat walks past. Rae cannot believe his bad luck. He hears rustling in some bushes in the near-blackness and knows that it’s Christie making his escape. He will be caught just two days later by a policeman next to Putney Bridge in south-west London and Rae will never get his scoop. Christie will sell his full story to Rae’s rival, the equally legendary Harry Procter of the Sunday Pictorial, who had secured the story of the sadistic killer Neville Heath in 1946.

It was less than three weeks since Mr Justice Finnemore had donned the black cap and, shedding tears of pity for humanity, sentenced John Christie to death for multiple murder, adding the traditional ‘May God have mercy on your soul,’ mercy which Christie had not shown his victims. In the condemned cell the balding and stooped fifty-five-year-old, his huge domed forehead creased with tension, ineffectual and pathetic and indistinguishable in a crowd if it were not for his depraved crimes, was brought to his feet as the execution party arrived. It was a few minutes before nine o’clock in the morning.

A chaplain had spent the last hour with Christie in quiet contemplation, but now God’s representative was sidelined as Britain’s chief executioner Albert Pierrepoint entered the cell, followed by his assistant, the chief prison officer and another officer. In silence Christie’s glasses were removed and his hands pinioned tightly behind his back. Pierrepoint and his assistant had arrived at the prison the afternoon before and observed Christie from a distance to weigh up the length of drop required, and tests had been carried out, with a bag of sand standing in for Christie, to confirm the gallows were in good working order. That bag of sand had been left hanging all night to stretch the rope.

Christie hadn’t been held at Pentonville before and during his trial, but at Brixton. While there he was examined by a succession of psychiatrists, all of whom felt nauseated and repulsed by him. At Brixton Christie had bragged about his murders to other inmates, comparing himself to another serial killer hanged just a few years before, acid bath killer John George Haigh. Like Haigh, Christie had killed at least six people, but said that he had been aiming for twelve victims. This bravado was totally at odds with his nondescript personality and appearance. His trial had lasted four days, and the jury took just an hour and twenty minutes to unanimously find him guilty. After he was condemned to death and sent to Pentonville to await execution, he was very withdrawn. One man who had known Christie during the First World War visited him just two days before his execution. Christie told him, ‘I don’t care what happens to me now. I have nothing left to live for.’

Christie was quiet as he was led to the gallows, the prison officers on either side of him. The sheriff, the prison governor and the medical officer were waiting as Christie came in and was escorted to stand on the trapdoors through which he would drop, the spot marked in the interests of speed and efficiency. Christie’s feet were placed directly across where the trapdoors divided. Pierrepoint then put a white cap over Christie’s head and placed the noose around his neck, while his assistant pinioned his legs to prevent him from trying to jump off the trapdoors. Everything ready, Pierrepoint pulled the gallows lever. Christie went down swiftly and smoothly. The medical officer then inspected his broken body in the pit below the trapdoors and satisfied himself that he was medically dead. After the body was left hanging for an hour, an inquest on Christie took place before he was buried in the prison grounds in an unconsecrated grave.

IT’S LATE EVENING and the weather is cool but not unpleasant and the crowds are bustling in and out of the station entrance. Outside, the newspaper boy has long since shut down his stand for the night, the late edition of the twopenny Evening Standard already on its way to wrapping tomorrow’s fish-and-chip supper. Soldiers on leave walk past the Edwardian splendour of Bailey’s Hotel just south of the station with girlfriends on their arms. A tin-hatted air raid warden crosses the road, his torch pointed down and covered with tissue, obeying his own instruction ‘Put that light out!’ The white band on his arm matches the stripes painted down the middle of the road and the horizontal stripes daubed on the lamp posts to help drivers unable to use their headlamps in the blackout.

The war is still raging. Just the day before, the first V2 rocket, Hitler’s new secret weapon, had hit the area of Chiswick a few miles south-west of Gloucester Road. Travelling at 3,000 miles an hour and carrying a ton of explosive, the V2 was even more powerful than the V1 ‘doodlebugs’ that had brought terror to the streets of London that summer, reminding Londoners of the sustained devastation of the Blitz four years earlier.

Two men walk briskly down Gloucester Road. They are fortified in the chilly air by the beer they have drunk at tenpence a pint at the Goat, a gaudy Victorian pub in nearby High Street Kensington. One is tall and slim, the other slightly shorter but well built. They are both thirty-five years old, smartly dressed in well-cut suits and ties, two youngish men about wartime town. The taller man with the angular face and styled mop of dark hair and pencil moustache is William McSwan, a Scot known to his friends as Mac. The man next to him is John George Haigh, whom Mac counts as his trusted friend and drinking buddy. Haigh has always been known within his family as George, but Mac calls him John. They have known each other for eight or nine years, although they lost touch for much of that time and only recently met again.

Haigh first met Mac in late 1935, when Mac’s father Donald advertised for a secretary/chauffeur. Donald McSwan had previously been a local government minister in Scotland, but relocated to London with his wife Amy and son William to join the London County Council. Soon after he invested some of his savings in an amusement arcade in Tooting, south-west London, and his son William was employed as manager of the arcade, which operated pinball tables. Haigh quickly became trusted by the McSwans, especially Mac, the two of them frequenting the Goat in the evenings. Haigh was always able to impress those around him. When Haigh moved on, he and the McSwans lost contact. It was only in the late summer of 1944 that Mac ran into Haigh again in the Goat, a meeting that Haigh no doubt wanted and perhaps planned to happen, and not just to rekindle the friendship.

For the previous two weeks they have spent a great deal of time together in the evenings. Haigh is now a salesman and bookkeeper for a small company, Hurstlea Products Ltd, in Crawley, West Sussex. His patter and personable manner are key assets in selling products, and his shrewd mind is adept at figures. But his expensive lifestyle is beyond his average salary. He is now running out of funds and seeking an opportunity to make some quick cash.

Mac has no idea that his friend was released from HM Prison Lincoln the previous year after serving a sentence for fraud and forgery. Nor that while in prison Haigh had done experiments on mice with sulphuric acid he stole from the prison tinsmith’s workshop, observing how the creatures dissolved. These tests had a purpose – little that Haigh does lacks a purpose, whether menial gestures or life decisions. His easy manner belies the fact that even his smiles are not spontaneous. Mac may know about Haigh’s car accident a few months before, when he suffered a head injury that caused bleeding into his mouth. But as they approach their destination, Mac is relaxed and grateful to his friend. Firstly, Haigh, always good with his hands, has promised to repair a broken pin table for him, although Mac’s father has already sold the amusement arcade, a fact not lost on Haigh over the previous fortnight. Secondly, and far more importantly, Haigh has promised to help his old friend with a pressing problem. Mac has been worried for some time. He is due to be conscripted into the army but is not a natural soldier and he has no wish to die. Haigh has promised to help him disappear until the war is over, leaving his business and personal affairs in the capable hands of his jovial friend. Mac has no idea how completely his drinking partner wants to help him.

Haigh is the dominant party in the friendship – socially at ease, interesting and proactive in conversation, the milder-mannered Mac happy to laugh along at his daring jokes and ideas. Haigh’s side-parted hair remains immaculately slicked back even though he wears no hat in the breezy night, his thin lips pursed between smiles, the upper topped by a small moustache that the vain Haigh likes to think makes him resemble the popular matinee idol Ronald Colman. If ever Mac wondered that his friend was not what he seemed, the clue is in his eyes. Slightly Asian in shape, his dark pupils stare out like fish eyes. Even when his lips are parted in a mechanised smile, those eyes are cold and scheming.

They chat cheerfully as they arrive at their destination directly opposite the Underground station, a basement room at 79 Gloucester Road which Haigh rents as a workshop. The bonhomie continues as Haigh thrusts out his arm to gesture his friend to go first. Mac is happy tonight, as with the help of his friend he is going to avoid being sent to war. As they walk down the steps into the small basement yard, fingering the ornate wrought-iron railings as they descend, Mac sees the blacked-out window complying with wartime regulations. Haigh knows what war is about, having experienced death at first hand. A few years before, during an air raid, he was chatting to a nurse and when the explosions got close took refuge in a doorway. A few minutes later he saw the nurse’s head rolling along the street. As they reach the door of the basement, little does Mac know that he is seeing his last natural light, the dark milky sea turning pitch black above him his last experience of open sky.

Inside, the basement room is sparsely furnished: a wooden work table, an oil drum, some small machine parts and tools. Mac doesn’t know that the forty-gallon oil drum is meant for him or that his friend has been accumulating quantities of acid by posing as ‘Technical Liaison Officer’ to ‘Union Group Engineering’ and suddenly acquiring a science degree on his business card. The carboys of acid may or may not be there that night. The focal point of the room is a drain in the middle of the floor, and this is impossible for Mac to miss. They continue to chat, Haigh showing Mac something he is working on.

Mac doesn’t see it coming. He’s hit with great force from behind on the back of the head. Once on the ground, two further blows make certain he is dead, the third transmitting to Haigh a ‘squashy’ feeling. The weapon is a blunt instrument – perhaps a leg removed from a pin table or more likely a piece of heavy metal piping that Haigh had procured in advance. Haigh then strips Mac of his watch, wallet and National Identity Card. Haigh’s eyes are still staring and intense, the windows to a clinical coldness and a frozen soul, but there are no smiles any more.

There are two theories about what happens next. In the first, Haigh panics and locks the door of the basement, hails a taxi and goes to a late-night drinking club in nearby Bayswater, where a few drinks calm him down. He then returns to the basement at about 2.30 a.m. and begins to clear up. This is when he possibly made an incision in Mac’s neck and gathered a cup of blood which he then drank, but this may well not have happened. The mice experiments demonstrating the effect of acid on animal tissue have given Haigh his big idea. If there is no body, there can surely be no murder charge. It takes Haigh two or three days to order the acid, and by then Mac is beginning to smell. The body worries Haigh, but it’s not a guilty conscience. This is Haigh’s first murder, and his panic is due to fear of hanging for murder rather than any belated compassion. When the acid arrives, Mac is placed in the oil drum and Haigh waits overnight for his friend to dissolve. The sludgy remains are then poured down the cellar drain.

The alternative theory is that Haigh buys a mincing machine from a shop called Gamages in Holborn and some swimming trunks (to wear while he works) in Bayswater. Then he greases the floor of the basement to prevent bloodstains. He cuts Mac into small pieces over the following three days, before chopping up the bones and boiling and mincing them. The floor is then washed with hot caustic soda to remove any evidence and it all goes down the drain. There is little to support this story, but the occupants next door to 79 Gloucester Road later say that the basement was very noisy at this time. The truth may be a mixture of the two versions.

After Mac’s disappearance Haigh wastes no time. Sending letters to Mac’s parents, Donald and Amy, apparently from their son in hiding, he manages to secure large sums of money from them over the following months which they think he is passing on to their son. Haigh’s cunning mind and beady eyes are now working overtime, revelling in his own ingenuity. Corpus delicti: no body, no proof of murder. These will not be the last dealings that Haigh has with the McSwan family. Mac’s murder has desensitised him, made him feel invincible. As he walks jauntily down the Gloucester Road with a spring in his step every day, perhaps whistling a favourite tune, nobody knows that the well-dressed man of business is a mercenary psychopath. But then why should they? Mac knew him well for years and had no idea at all.

Pointing at a small bluish scar on his forehead, John George Haigh’s father John spoke in an austere voice as he delivered one of his parables to his young son.

‘This is the brand of Satan. I have sinned, and Satan has punished me. If ever you sin, Satan will mark you with a blue pencil likewise.’

‘Well … mother isn’t marked,’ said the rapt son after a moment’s thought.

‘No, she is an angel,’ said his father.

Years later the son would learn that the cause of his father’s scar was a fragment of burning coal spat from the fire, but in John George Haigh’s eyes, his mother Emily would never fall from her angelic pedestal.

When John George was born to John and Emily Haigh in Stamford, Lincolnshire on 24 July 1909 Emily was already forty, and he was her only child. John had lost his job as a foreman at an electricity plant in Stamford just three months before his son’s birth. Emily would later say that the financial and emotional instability this caused at the time had affected her son in the womb and twisted his mind. John and Emily called their newborn George at home to avoid confusion with his father.

Soon after his son was born, John Haigh managed to find work further north at the Lofthouse Colliery in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, and they soon relocated to a small village called Outwood close to Wakefield. This was not such a wrench for them, as John and Emily were originally of Yorkshire stock, sturdy and strong-minded. Significantly in the light of later events, there was not a shred of mental illness in the family history, but a strong case could be made for religious mania. The Haighs were devout members of the Plymouth Brethren, an evangelical, non-ritualistic and anti-clerical branch of Protestantism. The Haighs followed the inflexible strictures of the sect to the very letter and line of the Old Testament. The household that John George Haigh was born into was therefore different from most homes of the time. His grandparents had been among the pioneers of the Brethren, holding informal assemblies instead of worshipping in church. Ascetic and God-fearing, the Brethren’s piety shut them off from the world at large, which they considered full of sinners and dangerous to their souls.

John Senior spoke in negatives: ‘Thou shalt not …’; ‘Do not …’ No entertainment or sport of any kind was allowed. No magazines or newspapers, just the Bible in its oldest, purest form. This strong sense of sacrifice and austerity was the source of the Brethren’s strength, and control the means of building it. John Senior promised that to behave righteously ‘would please the Lord’. Heaven and the afterlife were the reward for obeying; eternal damnation and descent into Hell the punishment for disobedience. ‘It is a sin to be happy in this world,’ John Senior was fond of saying. The next life mattered far more than this. Young George, his only child, was steeped in this rhetoric from the moment he could grasp meaning. ‘The worms that will destroy this body’ were irrelevant if a life of sacrifice were followed, John Senior told his son, and the soul was all that mattered. But from an early age George began to develop his own idea about eternal sleep – physical death meant nothing, merely being another sacrifice.

With evil and corruption from the outside world being devilish threats and temptations to be steadfastly avoided, John built a ten-foot (three metre) fence around their garden. Young George was truly penned in. There were no peering or prying eyes, no chatting neighbours. His mother Emily was George’s beacon, his light; all of his trust went into her. He loved John Senior, but feared him in equal measure. The two emotions dominated the young boy: love of his parents and their beliefs, tempered by fear, a microcosm of his love and fear of God. His enforced separation from his peers (as far as possible) added to the strength of his beliefs, just as John and Emily wished. When George became John George Haigh the man, he would stay on deeply loving terms with his parents, especially his mother, until he died.

George loved animals as a little boy, nurturing the rabbits he was allowed, as they were God’s creatures, and even secretly feeding the dogs of strangers in the street. He was also prone to accidents, like many young children. At the age of seven he hit his ear hard on a wardrobe in the bedroom, drawing blood, and a few years later cut his scalp when he fell down the stairs. On neither occasion was medical help sought, Emily’s caring hands keeping it in the family. Also aged seven, George entered a private preparatory school with a strict disciplinary regime, no doubt to John’s satisfaction. It was at about this time, during the First World War, that John and Emily took their son on his first holiday to the seaside. However, while there a German Zeppelin raid occurred, and George was so disturbed by the destruction he saw that the family rushed home to Outwood and the high fence.

In 1920 at the age of eleven George entered Wakefield Grammar School, meant for children in the area with the most academic potential, remaining there until the age of seventeen. His teachers later remembered him as a ‘mischievous boy’, undoubtedly trying to find a semblance of individuality outside the parental home. Flashes of the later John George Haigh were beginning to appear. He had a quick mind, and his parents’ strictures meant that he was always very well groomed and dressed, a habit that remained a lifelong one for him. He was also becoming a good liar, seeking to avoid the displeasure and reprimands of John Senior for minor misdemeanours which to a Brethren father were major lapses.

John George was also developing a deep passion for music, becoming entranced by the sound of the imposing pipe organ in Wakefield Cathedral, and soon he was playing the piano very well himself. John George had a good voice too, and this led to him being awarded a choral scholarship to the cathedral choir. The angelic image of the choirboy suited him in the context of his family, even though churchgoing in the conventional sense was not the Brethren way. The irony of this phase in his life would later seem almost grotesque, but there was an element to the time he spent in the cathedral that was less innocent than appearances suggested.

He would later say that he spent many hours in the cathedral staring at a statue of the bleeding Christ, a physical embodiment of the Messiah he had avidly read about and whose life and teachings his father had drummed into his head. But this could also be early evidence of John George Haigh’s unhealthy interest in blood. He also claimed that he drank his own urine from the age of eleven, but this has never been verified. Much of what Haigh said later must be viewed with caution – he was an expert manipulator, and would soon start putting that to profitable use.

As a teenager, John George began to have religious or at least spiritual dreams, although perhaps this is not surprising considering how much of his waking life was consumed with such matters. In some Christ would appear, and in one a ladder featured and helped him climb to the moon. John and Emily naturally saw this as religiously significant. Was he subconsciously trying to escape the strictures of his family? It does show that he had a vivid imagination and a strong inner life. He was also living in two worlds: the repressed one of his parents and the Brethren, and the world of the cathedral, where his real personality could manifest itself. This got him into the habit of living his life in compartments, concealing aspects of himself when it suited him in order to gain the confidence of people.

When he was seventeen, in 1926, Haigh left Wakefield Cathedral. Alongside his musical talent and passion, he was interested in machines and so went to work for a motor engineering firm to train as a mechanic, although after a while the physical labour the job entailed began to pall. Fastidious in appearance and lazy by nature, even the lure of learning how engines worked was not enough, and he took a desk job with an insurance company. He did well there, and soon found that his shrewd and calculating mind made him a natural at sales. In 1930, at the age of twenty-one, Haigh moved on to work for a company specialising in insurance, estate agency and advertising. This venture was quickly very successful, and Haigh proved himself an excellent broker, securing a £30,000 contract to insure a dam-building project in Egypt. However, his future tendencies came to the fore, and he was fired after being suspected of stealing money from an office cash box. The irrepressible Haigh then founded an advertising agency, Northern Electric Newspapers Ltd, and this was even briefly floated on the London Stock Exchange.

The year 1934 was a watershed for Haigh. Three weeks short of his twenty-fifth birthday, on 6 July he married twenty-one-year-old beauty Beatrice Hammer. He moved out of his parents’ house in Outwood and stopped attending Brethren assemblies. What they thought of this is not recorded, but it is unlikely they were happy about it, having controlled him for so long. This was the real beginning of his waywardness, his disposition for dishonesty starting to grow. Haigh had realised there were easier ways of making money than working for a living.

A newspaper article about a car swindle inspired him to have a go himself. These were the Depression years, and while Britain did not suffer as greatly as the USA, they were times of great hardship. Many businesses got into trouble or closed down and unemployment was rising. Haigh approached a garage in financial difficulty and through it bought cars, paying in instalments. He would forge the signatures and handwriting of real people he didn’t know but probably found in a telephone directory, and then sell the cars on after only one or two small payments had been made. Haigh discovered that he possessed a natural ability for forgery and this would become the focus of his future criminal career. It worked well for a few months, and he made a lot of money, but then he was caught. On 22 November 1934 he was sentenced to fifteen months for fraud and forgery at Leeds Assizes.

‘May God give me time to redeem the past, and to make you happy in your later years,’ wrote Haigh to his horrified parents from prison. While incarcerated he received a letter from the Plymouth Brethren politely ostracising him, as he had brought shame on them. He was shocked and devastated, this having been the very centre of his existence since he was a baby. His mother Emily later thought that this embittered her only son and changed him, but of course he was already a convicted criminal when he received the letter. For John and Emily, finding reasons for their son’s criminality would prove increasingly difficult. In their eyes he had been brought up strictly, correctly and in a God-fearing environment. It was not their nurture but the world that had ruined him, diseased his pure nature, the very reason John had erected that fence years earlier.

Haigh was released on 8 December 1935 and returned to live with his parents. While he was in prison, Beatrice – they had been married just over four months when he was convicted – had discovered she was pregnant, had the baby, given it up for adoption and left him. John and Emily now gave him the money to start a dry-cleaning business with a financial partner. This was immediately successful, Haigh’s natural sales ability being a great asset. Soon after the first shop opened, it was cleaning over 2,000 garments a week, but fate then dealt a cruel blow. Haigh’s partner was killed in a car accident and, short of money, he was forced to put the firm into voluntary liquidation. In 1936, he went south for the first time, to London.

There he answered an advertisement for a secretary/chauffeur to the McSwans, a family then living in Wimbledon who would play a major part in Haigh’s life over the next ten years, and be for ever linked to his name. As we have seen, he impressed them and became great friends with the son, William or Mac. After some months working for the McSwans, Haigh moved on, turning criminal again. He set up fake solicitor’s offices using the name of reputable real firms and sold imaginary shares in genuine companies at below-market prices, hooking the greedy. Deposits for share options flooded in, and Haigh often bought goods with the proceeds so as not to have too much unexplained cash, then swiftly moved on. He was now a fully fledged confidence man, a ‘grifter’, repeating the scam in different locations in and around London. But once again Haigh was caught – in Guildford, Surrey. On 24 November 1937 he was sentenced to four years at Surrey Assizes for dishonestly obtaining over £3000, a small fortune then.

Haigh was in prison when the Second World War broke out in September 1939, not being released until 13 August 1940, on licence, just before the Battle of Britain and the Blitz started. He became a fire warden in Victoria, central London, not far from the Houses of Parliament. It was during this time that he saw a nurse he had been talking to decapitated by a German bomb. In February 1941 Haigh, like every fit young man, registered for military service, although he never intended to fight and in 1943 would fail to attend a military medical board. He had just been released from prison yet again. On 11 June 1941, still on licence, he was sentenced to twenty-one months hard labour for stealing household goods and sent to Lincoln Prison, not far from his birthplace Stamford.

‘If you are going to go wrong, go wrong in a big way, like me. Go after women – rich, old women who like a bit of flattery. That’s your market, if you are after big money,’ Haigh is reported to have said to other prisoners. He may not have followed his own advice yet (at least there is no proof that he had) but this would prove to be his eventual modus operandi. He got on well with the other prisoners – he was gregarious, boastful and mischievous, the Brethren boy nowhere to be seen any more. Inmates on outside work duty would supply him with field mice they caught, but they probably did not know what he was doing with them. Haigh’s work duty was in the prison tinsmith’s shop, and he dissolved the mice in sulphuric acid he obtained there. He found that within ten minutes the acid darkened and the temperature rose to one hundred degrees Celsius. After thirty minutes only black sludge remained of the mice.