Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1: A Perfectly Normal Family

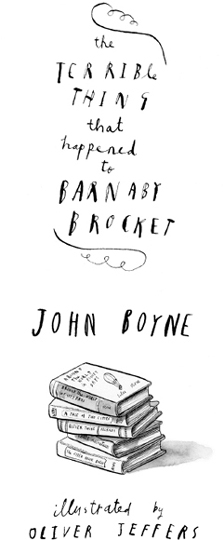

Chapter 2: The Mattress on the Ceiling

Chapter 3: Barnaby the Kite

Chapter 4: The Best Day of Barnaby’s Life So Far

Chapter 5: The Magician on the Bridge

Chapter 6: The Terrible Thing that Happened at Mrs Macquarie’s Chair

Chapter 7: Approaching from a North-westerly Direction

Chapter 8: The Coffee Farm

Chapter 9: Something to Read at Last

Chapter 10: The Worst Jeremy Potts Ever

Chapter 11: The Cotton-Bud Prince

Chapter 12: A Star is Born

Chapter 13: Little Miss Kirribilli

Chapter 14: The Photograph in the Newspaper

Chapter 15: The Fire in the Studio

Chapter 16: The Little Jelly that Caused So Much Trouble

Chapter 17: The Postcard that Smelled Like Chicken

Chapter 18: Freakitude

Chapter 19: Setting Free the Freaks

Chapter 20: Stanley’s Wish List

Chapter 21: 20,000 Leagues Above the Earth

Chapter 22: The Space Walk

Chapter 23: Everything They’ve Told You is True

Chapter 24: Whatever Normal Means

Chapter 25: That Familiar Floating Feeling

Chapter 26: The Most Magnificent City in the World

About the Author

Also by John Boyne

Copyright

For Philip Ardagh

About the Book

There’s nothing unusual about the Brockets.

Boring, respectable and proud of it, they turn up their noses at anyone different. But from the moment Barnaby Brocket comes in to the world, it’s clear he’s anything but normal. To his parents’ horror, Barnaby defies the laws of gravity – and floats.

Then one fateful day, the Brockets decide enough is enough. Barnaby has to go . . .

Betrayed, frightened and alone, Barnaby floats into the path of a very special hot air balloon – and so begins a magical journey around the world.

Chapter 1

A Perfectly Normal Family

THIS IS THE story of Barnaby Brocket, and to understand Barnaby, first you have to understand his parents; two people who were so afraid of anyone who was different that they did a terrible thing that would have the most appalling consequences for everyone they loved.

We begin with Barnaby’s father, Alistair, who considered himself to be a completely normal man. He led a normal life in a normal house, lived in a normal neighbourhood where he did normal things in a normal way. His wife was normal, as were his two children.

Alistair had no time for people who were unusual or who made a show of themselves in public. When he was sitting on a Metro train and a group of teenagers were talking loudly nearby, he would wait until the next stop, jump off and move to a different carriage before the doors could close again. When he was eating in a restaurant – not one of those fancy new restaurants with difficult menus and confusing food; a normal one – he grew irritated if his evening was spoiled by waiters singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to some attention-seeking diner.

He worked as a solicitor at the firm of Bother & Blastit in the most magnificent city in the world – Sydney, Australia – where he specialized in last wills and testaments, a rather grim employment that suited him down to the ground. It was a perfectly normal thing, after all, to prepare a will. Nothing unusual in that. When clients came to see him in his office, they often found themselves a little nervous, for drawing up a will can be a difficult or distressing matter.

‘Please don’t upset yourself,’ Alistair would say on such occasions. ‘It’s perfectly normal to die. We all have to do it one day. Imagine how awful it would be if we lived for ever! The planet would collapse under all that excess weight.’

Which is not to say that Alistair cared very much about the planet’s welfare; he didn’t. Only hippies and new age types worried about things like that.

There is a belief held by some, particularly by those who live in the Far East, that each of us – you included – comprises one half of a couple separated before birth in the vast and complex universe, and that we spend our lives searching for that detached soul who can make us feel whole again. Until that day comes, we all feel a little out of sorts. Sometimes completeness is found through meeting someone who, on first appearances, seems to be the opposite of who we are. A man who likes art and poetry, for example, might end up falling in love with a woman who spends her afternoons up to her elbows in engine grease. A healthy-eating lady with an interest in outdoor sports might find herself drawn to a fellow who enjoys nothing more than watching them from the comfort of his living-room armchair with a beer in one hand and a sandwich in the other. It takes all sorts, after all. But Alistair Brocket always knew that he could never share his life with someone who wasn’t as normal as he was, even though that in itself would have been a perfectly normal thing to do.

Which brings us to Barnaby’s mother, Eleanor.

Eleanor Bullingham grew up on Beacon Hill, in a small house overlooking the northern beaches of Sydney. She had always been the apple of her parents’ eyes, for she was indisputably the best-behaved girl in the neighbourhood. She never crossed the street until the green man appeared, even if there wasn’t a car anywhere in sight. She stood up to let elderly people take her seat on the bus, even if there were dozens of empty seats already available to them. In fact, she was such a well-mannered little girl that when her grandmother Elspeth died, leaving her a collection of one hundred vintage handkerchiefs with her initials, EB, carefully embroidered onto each one, she resolved one day to marry a man whose surname also began with B in order that her inheritance would not go to waste.

Like Alistair, she became a solicitor, specializing in property work, which, as she told anyone who asked her, she found frightfully interesting.

She accepted a job at Bother & Blastit almost a year after her future husband, and was a little disappointed at first when she looked around the office to discover how many of the young men and women employed there were behaving in a less than professional manner.

Very few of them kept their desks in any sort of tidy condition. Instead, they were covered with photographs of family members, pets or, worse, celebrities. The men tore their used takeaway coffee cups into shreds as they talked loudly on the telephone, creating an unsightly mess for others to clean up later, while the women appeared to do nothing but eat all day, buying small snacks from a trolley that reappeared every few hours laden down with sweet treats in brightly coloured packaging. Yes, this was normal behaviour by the current standards of what was normal, but still, it wasn’t normal normal.

At the beginning of her second week at the firm, she found herself walking up two flights of stairs to a different department in order to deliver a hugely important document to a colleague who needed it without a moment’s delay or the whole world would grind to a halt. Opening the door, she tried not to stare at the signs of disorder and squalor that lay before her in case it made her regurgitate her breakfast. But then, to her surprise, she saw something – or someone – who made her heart give the most unexpected little leap, like an infant gazelle hurdling triumphantly across a stream for the first time.

Sitting at a corner desk, with a neat pile of paperwork before him separated into colour-coded groups, was a rather dashing young man, dressed in a pinstripe suit and sporting neatly parted hair. Unlike the barely house-trained animals who were working around him, he kept his desk tidy, the pens and pencils gathered together in a simple storage container, his documents laid out efficiently before him as he worked on them. There wasn’t a picture of a child, a dog or a celebrity anywhere in sight.

‘That young man,’ she asked a girl sitting at the desk closest to her, stuffing her face with a banana nut muffin, the crumbs falling across her computer keyboard and getting lost for ever between the keys. ‘The one sitting in the corner. What’s his name?’

‘You mean Alistair?’ said the girl, running her teeth along the inside of the wrapper just in case there was any sticky toffee sauce left behind. ‘The most boring man in the universe?’

‘What’s his surname?’ asked Eleanor hopefully.

‘Brocket. Rotten, isn’t it?’

‘It’s perfect,’ said Eleanor.

And so they were married. It was the normal thing to do, particularly after they had been to the theatre together (three times), a local ice-cream parlour (twice), a dancehall (only once; they hadn’t liked it very much – far too much jiving going on, too much of that nasty rock and roll music), and on a day trip to Luna Park, where they took photographs and made pleasant conversation until the sun began to descend and the lights gleaming from the clown’s giant face made him look even more terrifying than usual.

Exactly a year after their happy day, Alistair and Eleanor, now living in a normal house in Kirribilli on the Lower North Shore, welcomed their first child, Henry, into the world. He was born on a Monday morning on the stroke of nine o’clock, weighed precisely seven pounds and appeared after only a short labour, smiling politely at the doctor who delivered him. Eleanor didn’t cry or scream when she was giving birth, unlike some of those vulgar mothers whose antics polluted the television airwaves every night; in fact, the birth was an extremely polite affair, ordered and well-mannered, and nobody took any offence at all.

Like his parents, Henry was a very well-behaved little boy, taking his bottle when it was offered to him, eating his food, looking absolutely mortified whenever he soiled his nappy. He grew at a normal rate, learning to speak by the time he turned two and understanding the letters of the alphabet a year later. When he was four, his kindergarten teacher told Alistair and Eleanor that she had nothing good or bad to report about their son, that he was perfectly normal in every way, and as a reward they bought him an ice cream on the way home that afternoon. Vanilla flavoured, of course.

Their second child, Melanie, was born on a Tuesday three years later. Like her brother, she presented no problems to either nurses or teachers, and by the time her fourth birthday had arrived, when her parents were already looking forward to the arrival of another baby, she was spending most of her time reading or playing with dolls in her bedroom, doing nothing that might mark her out as different from any of the other children who lived on their street.

There was really no doubt about it: the Brocket family was just about the most normal family in New South Wales, if not the whole of Australia.

And then their third child was born.

Barnaby Brocket emerged into the world on a Friday, at twelve o’clock at night, which was already a bad start as Eleanor was concerned that she might be keeping the doctor and nurse from their beds.

‘I do apologize for this,’ she said, perspiring badly, which was embarrassing. She had never perspired at all when giving birth to Henry or Melanie; she had simply emitted a gentle glow, like the dying moments of a forty-watt bulb.

‘It’s quite all right, Mrs Brocket,’ said Dr Snow. ‘Children will appear when they appear. We have no way of controlling these things.’

‘Still, it is rather rude,’ said Eleanor before letting loose a tremendous scream as Barnaby decided that his moment was upon him. ‘Oh dear,’ she added, her face flushed from all these exertions.

‘There’s really nothing to worry about,’ insisted the doctor, getting himself into position to catch the slippery infant – rather like a rugby player stepping back on the field of play, one foot rooted firmly in the grass behind him, the other pressed forward in the soil, his two hands outstretched as he waits for the prize to be thrown in his direction.

Eleanor screamed again, then lay back, gasping in surprise. She felt a tremendous pressure building inside her body and wasn’t sure how much longer she could stand it.

‘Push, Mrs Brocket!’ said Dr Snow, and Eleanor screamed for a third time as she forced herself to push as hard as she could while the nurse placed a cold compress on her forehead. But rather than finding this a comfort, she began to wail loudly and then uttered a word she had never uttered in her life, a word that she found extremely offensive whenever anyone at Bother & Blastit employed it. It was a short word. One syllable. But it seemed to express everything she was feeling at that particular moment.

‘That’s the stuff,’ cried Dr Snow cheerfully. ‘Here he comes now! One, two, three, and then a final giant push, all right? One . . .’

Eleanor breathed in.

‘Two . . .’

She gasped.

‘Three!’

And now there was a terrific sensation of relief and the sound of a baby crying. Eleanor collapsed back on the bed and groaned, glad that this horrible torture was over at last.

‘Oh dear me,’ said Dr Snow a moment later, and Eleanor lifted her head off the pillow in surprise.

‘What’s wrong?’ she asked.

‘It’s the most extraordinary thing,’ he said as Eleanor sat up, despite the pain she was in, to get a better look at the baby who was provoking such an abnormal response.

‘But where is he?’ she asked, for he wasn’t being cradled in Dr Snow’s hands, nor was he lying at the end of the bed. And that was when she noticed that both doctor and nurse were not looking at her any more, but were staring with open mouths up towards the ceiling, where a new-born baby – her new-born baby – was pressed flat against the white rectangular tiles, looking down at the three of them with a cheeky smile on his face.

‘He’s up there,’ said Dr Snow in amazement, and it was true: he was. For Barnaby Brocket, the third child of the most normal family who had ever lived in the southern hemisphere, was already proving himself to be anything but normal by refusing to obey the most fundamental rule of all.

The law of gravity.

Chapter 2

The Mattress on the Ceiling

BARNABY WAS DISCHARGED from hospital three days later and brought home to meet Henry and Melanie for the first time.

‘Your brother’s a little different to the rest of us,’ Alistair told them over breakfast that morning, choosing his words carefully. ‘I’m sure it’s only a temporary thing but it’s very upsetting. Just don’t stare at him, all right? If he thinks he’s getting a reaction, it will only encourage his foolishness.’

The children looked at each other in surprise, unsure what their father could possibly mean by this.

‘Does he have two heads?’ asked Henry, reaching for the marmalade. He liked a bit of marmalade on his toast in the mornings. Although not in the evenings; then, he preferred strawberry jam.

‘No, of course he doesn’t have two heads,’ replied Alistair irritably. ‘Who on earth has two heads?’

‘A two-headed sea monster,’ said Henry, who had recently been reading a book about a two-headed sea monster named Orco which had caused any amount of mayhem beneath the Indian Ocean.

‘I can assure you that your brother is not a two-headed sea monster,’ said Alistair.

‘Does he have a tail?’ asked Melanie, gathering up the empty bowls and stacking them neatly in the dishwasher. The family dog, Captain W. E. Johns, a canine of indeterminate breed and parentage, looked up at the word ‘tail’ and began to chase his own around the kitchen, spinning in a circular direction until he fell over and lay on the floor, panting happily, delighted with himself.

‘Why would a baby boy have a tail?’ asked Alistair, sighing deeply. ‘Really, children, you have the most extraordinary imaginations. I don’t know where you get them from. Neither your mother nor I have any imagination at all and we certainly didn’t bring you up to have one.’

‘I’d like to have a tail,’ said Henry thoughtfully.

‘I’d like to be a two-headed sea monster,’ said Melanie.

‘Well, you don’t,’ snapped Alistair, glaring at his son. ‘And you aren’t,’ he added, pointing at his daughter. ‘So let’s just get back to being normal human beings and make sure this place is spick and span, all right? We have a guest coming this morning, remember.’

‘But he’s not a guest, surely,’ said Henry, frowning. ‘He’s our little brother.’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Alistair after only the briefest of pauses.

It was a little over an hour later when Eleanor pulled up outside in a taxi, holding a restless Barnaby in her arms.

‘You’ve got a lively one there,’ said the driver as he turned the engine off, but Eleanor ignored the remark as she disliked getting into conversations with strangers, particularly those who worked in the service industry. Her handbag fell into the gap between the two front seats, and as she reached for it, she let go of the baby for a moment and he floated off her knees, drifted upwards and bumped his head on the ceiling.

‘Ow,’ gurgled Barnaby Brocket.

‘You want to keep a hold of that lad,’ remarked the taxi driver, staring at him with world-weary eyes. ‘He’ll get away from you if you’re not careful.’

‘Thirty dollars, was it?’ asked Eleanor, handing across a twenty and a ten as she realized that yes, he might. If she wasn’t careful.

As she entered the house, the children ran to greet their mother, almost knocking her over in their excitement.

‘But he’s so small,’ said Henry in surprise. (In this regard at least, Barnaby was perfectly normal.)

‘He smells delicious,’ said Melanie, giving him a good sniff. ‘Like a mixture of ice cream and maple syrup. What’s his name anyway?’

‘Can we call him Jim Hawkins?’ asked Henry, who had taken to classic adventure stories in a big way.

‘Or Peter the Goatherd?’ asked Melanie, who always followed where her elder brother led.

‘His name is Barnaby,’ said Alistair, coming over now and placing a kiss on his wife’s cheek. ‘After your grandfather. And your grandfather’s grandfather.’

‘Can I hold him?’ asked Melanie, reaching forward, her arms outstretched.

‘Not just now,’ said Eleanor.

‘Can I hold him?’ asked Henry, whose arms reached further than his sister’s, as he was three years older.

‘No one is holding Barnaby,’ snapped Eleanor. ‘No one except your father or me. For the time being anyway.’

‘I’d rather not hold him just now, if it’s all the same to you,’ said Alistair, staring at his son as if he was something that had escaped from a zoo and should be sent back there before he caused any damage to the soft furnishings.

‘Well, he’s your responsibility too,’ snapped Eleanor. ‘Don’t think I’m taking care of this . . . this . . .’

‘Baby?’ suggested Melanie.

‘Yes, I suppose that’s as good a word as any. Don’t think I’m taking care of this baby all on my own, Alistair.’

‘I’m happy to help, of course,’ said Alistair, looking away. ‘But you are his mother.’

‘And you’re his father!’

‘He seems to have bonded with you though. Look at him.’

Alistair and Eleanor looked down at Barnaby’s face and he smiled up at them, kicking his arms and legs in delight, but neither parent smiled back. Henry and Melanie looked at each other in surprise. They weren’t used to their parents speaking in such a brusque fashion. They fished out the present they’d bought the previous day by pooling their pocket money.

‘It’s for Barnaby,’ said Melanie, handing it across. ‘To welcome him into the family.’ In her hands she held a small gift-wrapped box, and Eleanor felt her heart soften a little at the welcome they were showing their little brother. She reached out to take the gift, but the moment she did so, Barnaby began to float upwards once again, his blanket slipping away from him and falling to the floor as he drifted towards the ceiling, which was a much further distance to travel than the roof of the taxi cab. It was also much harder on his head.

‘Ow,’ grunted Barnaby Brocket, his tiny body stretched out flat as he looked down at his family, a decidedly grumpy expression on his face now.

‘Oh, Alistair!’ cried Eleanor, throwing up her arms in despair. Henry and Melanie said nothing; they simply stared up with their mouths wide open and expressions of wonder on their faces.

Captain W. E. Johns appeared, yawning, roused from sleep, and looked at the family that kept him fed, watered and imprisoned before following the direction of the children’s gaze until he too saw Barnaby on the ceiling, at which point his tail began to wag fiercely and he started to bark.

‘Bark!’ he barked. ‘Bark! Bark! Bark!’

A little later – although not quite as soon as you might expect – Alistair climbed on a chair to retrieve his son, taking charge of him now as Eleanor had retired to bed with a mug of hot milk and a headache. Reluctantly, he gave Barnaby his bottle, then changed his nappy, placing a new one under the baby’s bottom just as Barnaby decided to go again, in a perfect golden arc in the air. Finally he placed him in his basket, clipping the straps from Henry’s rucksack across the top so he couldn’t float up; at last Barnaby went to sleep and probably dreamed of something funny.

‘Melanie, keep an eye on your brother,’ said Alistair, positioning his daughter in the seat next to him. ‘Henry, come with me please.’

Father and son crossed the garden to their neighbour’s house and knocked on the front door.

‘What do you need, Brocket?’ asked grumpy old Mr Cody, picking a flake of tobacco from between his front teeth and flicking it to the ground between their feet.

‘The loan of your van,’ explained Alistair. ‘And its accompanying trailer. Just for an hour or two, that’s all. And of course I’ll compensate you for the gas.’

Permission granted, Alistair and Henry drove across the Harbour Bridge into the city and made their way to a department store on Market Street, where they purchased three large mattresses, each of which was designed for a double bed, a box of twelve-inch nails and a hammer. Returning home, they dragged the mattresses into the living room, where Melanie was sitting exactly where they’d left her, staring at her sleeping baby brother.

‘How was he?’ asked Alistair. ‘Any problems?’

‘No,’ said Melanie, shaking her head. ‘He’s been asleep the whole time.’

‘Good. Well, take him into the kitchen, there’s a good girl. I have a job to do in here.’

He took two ladders from the garden shed and placed them at either end of the living room, then climbed one, holding the left-hand side of a mattress as he did so, while Henry climbed the other, holding the right.

‘Keep it steady now,’ said Alistair as he took the first long nail from his breast pocket and used the hammer to pin the corner of the mattress to the ceiling. The nail went through easily enough but met a bit of resistance in the floorboards of the upstairs room. Still, it didn’t take too long until he got it right.

‘Now the other corner,’ he said, moving his ladder across and nailing the next part of the mattress in place. He continued doing this for almost an hour, using twenty-four nails in total, and by the time he finished, the previously white ceiling had been covered over by the rather flowery design of a David Jones Bellissimo plush medium mattress.

‘What do you think?’ asked Alistair, looking down at his son for approval.

‘It’s unusual,’ replied Henry, considering it.

‘I’ll give you that,’ agreed Alistair.

By now, the sound of all that hammering had woken Barnaby and he was making a series of unintelligible gurgling sounds from his basket as Melanie tickled him under the chin and arms and generally made a nuisance of herself. Eleanor’s headache had grown worse too, and she’d come downstairs to find out what all that infernal banging was about. When she saw what her husband had done to the living-room ceiling, she stared at him, speechless, for a moment, wondering whether everyone in the house had gone quite mad.

‘What on earth . . .?’ she asked, struggling for words, but Alistair simply smiled at her and brought the basket into the centre of the living room, where he unclipped the rucksack cords to allow Barnaby to float upwards once again. This time, however, he didn’t bang his head against the ceiling and he didn’t say ‘Ow’. Instead, he had a much softer landing and seemed perfectly content to be left up there, playing with his fingers and examining his toes.

‘It works,’ said Alistair in delight, turning to his wife, expecting her to be pleased by what he had done, but Eleanor, a perfectly normal woman, was aghast.

‘It looks ridiculous,’ she cried.

‘But it won’t be for long,’ said Alistair. ‘Just until he settles down, that’s all.’

‘But what if he never settles down? We can’t leave him up there for ever.’

‘Trust me, he’ll get tired of all this floating business in due course,’ insisted Alistair, trying to be optimistic, despite the fact that he felt anything but. ‘Just wait, you’ll see. But until then we can’t have him bumping his head every time he gets away from us. He’ll damage his brain.’

Eleanor said nothing, just looked miserable. She lay down on the sofa and stared up at her son, stranded eleven feet above her, and wondered what she had ever done to deserve such a terrible misfortune. She was a perfectly normal woman, after all. She wasn’t the type to have a floating baby.

In the meantime, Alistair and Henry went about their business, installing the second mattress in the kitchen, directly over the place where Barnaby’s basket would be kept, and the third in his and Eleanor’s bedroom, for when he was asleep in his cot beside them at night.

‘All done,’ said Alistair, coming downstairs and finding Eleanor still lying on the sofa while Melanie sat on the floor next to her, reading Heidi for the seventeenth time. ‘Where’s Barnaby?’

Melanie pointed her index finger upwards but uttered not a word; her eyes were pinned to the page. Peter the Goatherd was speaking and she wanted to hear his every syllable. That boy had wisdom beyond his years.

‘Oh yes,’ said Alistair, frowning, wondering what he should do next. ‘Do you think it’s all right to leave him up there for the rest of the day?’

Melanie continued to read until she reached the end of a long paragraph, and then picked up her bookmark. She placed it carefully between pages 104 and 105 and set the novel on the cushion beside Eleanor before looking directly at her father. ‘You’re asking me whether she should leave Barnaby on the ceiling of our living room for the rest of the day,’ she said coolly.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ said Alistair, unable to look his daughter in the eye.

‘Barnaby,’ she repeated. ‘Who is only a few days old. You want to know whether I think it’s all right to just leave him stranded up there.’

There was a long pause.

‘I don’t care for your tone,’ said Alistair eventually, his voice quiet and filled with shame.

‘The answer to your question is no. No, I don’t think it’s all right to leave him up there like that.’

‘Well then,’ said Alistair, reaching for a chair in order to retrieve the boy. ‘Perhaps you could have just said so.’

At that moment the doorbell rang. It was Mr Cody from next door looking for the keys to his Ute and, having received no immediate answer, marching in to retrieve them without so much as a by-your-leave. Alistair put Barnaby back in his basket but forgot to tie the straps, and in a moment the boy was on the ceiling once again, resting comfortably against the mattress.

Mr Cody, who had lived a long time, fought in two world wars, shaken the hand of Roald Dahl, and seen many unusual things across seven decades, some of which he had understood and some of which he hadn’t, looked up and cocked his head to one side. He stroked his chin with one hand and ran his tongue slowly across his lips, first the upper lip, then the lower. Finally, shaking his head, he turned to Eleanor.

‘That’s not normal, that,’ he said, at which point Eleanor burst into tears and fled upstairs to throw herself on her bed, determined not to open her eyes in case she had to see the awful monstrosity of the third mattress pinned above her.

Chapter 3

Barnaby the Kite

WHEN FOUR YEARS passed and nothing had changed, Barnaby’s family had to accept that this wasn’t a phase after all; it was just the way their son had been born. Alistair and Eleanor took him to a local doctor, who examined him thoroughly and suggested that they give him a couple of pills and call him again in the morning, but this did nothing to improve matters. They took him to see an out-of-town specialist who placed him on a course of antibiotics, but still he continued to float, although he became completely immune to a bad flu that was raging through Kirribilli that week. Finally they drove him into the centre of Sydney for an appointment with a famous consultant, who simply shook his head and said that the boy would grow out of it in time.

‘Boys usually grow out of everything in the end,’ he said, smiling as he passed across a rather large invoice for the rather short time he’d spent examining Barnaby. ‘Their trousers. Their good behaviour. Their willingness to respect parental authority. You simply have to be patient, that’s all.’

None of which helped Alistair or Eleanor in the least and, in fact, only served to frustrate them even more.

Now Barnaby slept in the lower bunk in Henry’s room, where a couple of blankets had been stitched to the underside of his brother’s bed to prevent him from hitting his head against the springs.

‘It’s nice to be able to see our ceiling again, isn’t it?’ said Alistair, when the mattress in their bedroom was finally taken down. Eleanor nodded but said nothing. ‘It needs a fresh coat of paint though,’ he added, filling the space left by her silence. ‘There’s a great yellow square where the mattress used to be. You can make out the flower design.’

There was a whole set of difficult circumstances associated with Barnaby’s use of the bathroom, but perhaps it would be indelicate to go into them here. Suffice it to say that taking a shower was very difficult, a bath was out of the question, and using the toilet presented such a set of challenges that even a skilled contortionist would have found himself not quite up to the task.

In the evenings, when they would occasionally light up the barbecue for their evening meal, the family would sit around the garden table, Alistair, Eleanor, Henry and Melanie taking the four seats under the large sun shade while Barnaby hovered beneath its pointed peak, prevented from drifting off into the atmosphere by the strong green canvas that held him in place. He was banned from putting tomato ketchup on his hot dogs or burgers as it had a terrible habit of falling down on one or all of their heads.

‘But I like tomato ketchup,’ Barnaby would complain, thinking this was most unfair. He could, of course, say more than ‘Ow’ by now.

‘And I prefer not to have to shampoo my hair every day,’ replied his father.

At such times, Captain W. E. Johns would sit on the ground staring up at the boy, awaiting instructions; the dog had decided that this floating child was his sole master and would take direction from no other.

through