ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2RE 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books Ind Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Penchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2008

1

Copyright © Deyan Sudjic, 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by

any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner

and the above publisher of this book

Design by YES

978-0-14-190010-0

| Introduction: A World Drowning in Objects | |

| 1. | Language |

| 2. | Design and its Archetypes |

| 3. | Luxury |

| 4. | Fashion |

| 5. | Art |

| Sources of Quotations | |

| Picture Acknowledgements | |

| Index | |

Introduction

Never have more of us had more possessions than we do now, even as we make less and less use of them. The homes in which we spend so little time are filled with things. We have a plasma screen in every room, displacing state-of-the-art cathode-ray television sets just five years old. We have cupboards full of sheets; we have recently discovered an obsessive interest in the term ‘thread count’. We have wardrobes stacked high with shoes. We have shelves of compact discs, and rooms full of games consoles and computers. We have gardens stocked with barrows and shears and cutters and mowers. We have rowing machines we never exercise on, dining tables we don’t eat at, and triple ovens we don’t cook in. They are our toys: consolations for the unremitting pressures of acquiring the means to buy them and which infantilize us in our pursuit of them.

The middle classes have kitchens full of electric appliances that we buy, dreaming of the domestic fulfilment that we hope they will bring. Just as when fashion brands put their names to children’s clothes, a new stainless steel kitchen allows us the alibi of altruism when we buy it. We are secure in the belief that these are not indulgences but investments in the family. And our children have actual toys: boxes and boxes of them that they discard within days. And, with childhoods that grow shorter and shorter, the nature of these toys has also changed. McDonald’s has become the world’s largest distributor of toys, almost all of them branded merchandise linked to a film.

Nor have our possessions ever been bigger. They have swelled to match the obesity epidemic that afflicts most Western cultures. In part it’s the result of what is known as product maturity. When every household that is ever going to buy a television set has done so, all that is left for manufacturers is to persuade owners to replace their old sets by inventing a new category. Sometimes it’s a miniature version, but, preferably for the manufacturer, it will be bigger and so better than the previous designs. As a result TV screens have gone from 28 inches to 60 inches. Domestic ovens have turned into ranges. Refrigerators have become bloated wardrobes.

Like geese force fed grain until their livers explode, to make foie gras, we are a generation born to consume. Geese panic at the approach of the man with a metal funnel ready to be rammed forcibly down their throats, while we fight for a turn at the trough that provides us with the never-ending deluge of objects that constitutes our world. Some of us camp outside Apple stores to be the first to buy an iPhone. Some of us pay any price to collect replicas of running shoes from the 1970s. A few of us even use the Bentley Arnage to tell our fellow Premiership footballers that we are worth £10m, rather than the £2.5m that it takes to be able to afford to run a Continental.

The intricacies of model numbers, provenance and pedigree sustain a drooling pornography that fetishises sunglasses and fountain pens, shoes and bicycles, and almost anything that can be traded, collected, categorized, organized and ultimately posessed and owned.

It is just possible that we might be on the verge of a wave of revulsion against the phenomenon of manufacturing desire, against the whole avalanche of products that threatens to overwhelm us. However, there is no sign of it yet, despite the outbreak of millenarian anxiety about the doom that faces us if we go on binge-flying. Even the return of the selling of indulgences, a practice abandoned by the medieval church and now resurrected in the form of carbon offset payments, is not stopping us from changing cellphones every six months.

In my own life, I have to acknowledge that I have been fascinated by the glossy sheen of consumption while at the same time nauseous with self-disgust at the volume of what we all consume, and the shallow but sharp emotional tug that the manufacture of want exerts on us.

Objects, so many people believe, are the unarguable facts of everyday life. Dieter Rams, who for two decades was head of design at Braun, the German consumer electronics company, certainly did. He used to describe Braun’s shavers and food mixers as English butlers, discreetly invisible when not needed, but always ready to perform effortlessly when called upon. Such things have become rather more than that.

‘Clothes, food, cars, cosmetics, baths, sunshine are real things to be enjoyed in themselves,’ John Berger claimed in Ways of Seeing, (1972) the best-read contemporary analysis of visual culture to be published in the past half-century. He made a distinction between ‘real’ objects and what he saw as the manipulations of capitalism that make us want to consume them. ‘It is important… not to confuse publicity with the pleasure or benefits to be enjoyed from the things it advertises,’ he argued. ‘Publicity begins by working on a natural appetite for pleasure. But it cannot offer the real object of pleasure.’

Berger wrote Ways of Seeing from an uncomfortable vantage point halfway between Karl Marx and Walter Benjamin. His book was an attempt to demolish the conventional tradition of connoisseurship, and to establish a more political understanding of the visual world.

Publicity is the life of this culture [the culture of capitalism] – in so far as without publicity capitalism could not survive – and at the same time publicity is its dream.

Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their own interests as narrowly as possible. This was once achieved by extensive deprivation. Today in the developed countries it is being achieved by imposing a false standard of what is, and what is not desirable.

But even before the collapse of Communism and the explosion of the economies of China and India, understanding objects was more complicated than that. It is not just the imagery of advertising that is marshalled to manufacture desire. The ‘real’ things that Berger regards as having authentic qualities – the car with a door that shuts with an expensive click, and which evokes a 60-year tradition in doing so, the aircraft that integrate fuel efficiency with engineering elegance, and which makes mass tourism possible – are themselves susceptible to the level of analysis that he applies to the late portraits of Frans Hals and to Botticelli’s allegories. They are calculatingly designed to achieve an emotional response. Objects can be beautiful, witty, ingenious, sophisticated, but also crude, banal or malevolent.

If he were writing Ways of Seeing today, what Berger calls ‘publicity’ might just as well have been described as ‘design’. Certainly there is no shortage of those who have come to understand the word in as negative a way as Berger saw publicity.

Overuse of the word ‘designer’ has rubbed it clean of earlier meanings, or left it as a synonym for the cynical and the manipulative. Bulthaup, a German kitchen manufacturer whose products are essential props in any design conscious interior, even forbids the use of the word ‘design’ in any of its advertising. Nevertheless the design of objects can offer a powerful way of seeing the world. Berger’s book belongs to a crowded literature of art. However, since Roland Barthes wrote Mythologies in 1957, and the imprecisions of Jean Baudrillard’s The System of Objects, first published a decade later, few critics have subjected design to the same close analysis. It is an unfortunate gap. The architectural historian Adrian Forty comes close to Berger’s point of view with his book Objects of Desire (1986). But now that the world of objects has erupted so convulsively, spraying product unstoppably in every direction, there is a quantitatively and qualitatively different story to tell from the conventional narrative of the emergence of modernism as the deus ex machina to make sense of the machine age.

Both Barthes and Baudrillard were strikingly uninterested in any discussion of the role of the designer, preferring instead to regard the disposition of things as the physical manifestation of a mass psychology. Baudrillard, for example, professed to see the modern interior not as the product of design as a creative activity, but as the triumph of bourgeois values over an earlier, earthier reality:

We have more freedom in the modern interior, but this freedom is accompanied by a subtler formalism, and a new moralism. Everything now indicates the obligatory shift from eating, sleeping and procreating, to smoking, drinking, entertaining, discussing, looking and reading. Visceral functions have given way to functions determined by culture. The sideboard used to hold linen, crockery or food. The functional elements of today house books, knick knacks, a cocktail bar or nothing at all.

But this is special pleading from a boulevardier. Rather than repressing our primal desires, it seems that our material culture is more interested in indulging them.

Our relationship with our possessions is never straightforward. It is a complex blend of the knowing and the innocent. Objects are far from being as innocent as Berger suggested, and that is what makes them too interesting to ignore.

Chapter One

To start with the object that is closest to hand, the laptop with which I write these words was bought at an airport branch of Dixons. There is no one but me to blame for my choice. Not even what Berger called publicity. Some shops are designed to seduce their customers. Others leave them to make up their own minds.

Dior and Prada hire Pritzker Prize-winning architects to build stores on the scale of grand opera to reduce shoppers to an ecstatic consumerist trance. Not Dixons. A generic discount electronics store at Heathrow is no place for the seductions, veiled or unveiled, of the more elaborate forms of retailing. Nor can I ever remember Dixons advertising itself to try to persuade me to enter its doors, even if the companies whose products it sells do. In an airport, there isn’t the space or the time to be charmed or hypnotized, for nuances or irony. Transactions here are of the most brutal kind. There are no window displays. No respectful men in Nehru jackets and electronic ear prosthetics open doors for you. There are no layers of tissue paper wrapping for your purchases, or crisp new banknotes for your change. There is just the inescapable din of a mountain of objects piled high and sold not that cheaply to divert you.

As the waves of economy-class passengers ebb and flow on their way to the 7 a.m. departure for Düsseldorf, a few will browse among the digital cameras and the cellphones, and a few more will pick up a voltage adaptor. Every so often one of them will produce a credit card and buy something, knuckles white as they key in their PIN code for fear they will miss their flight. Consumption here is, on the face of it, the most basic of transactions – shorn of ceremony and elaboration, reduced to its raw essentials. Yet, even in an airport, buying is no simple, rational decision. Like an actor performing without make up, stripped of proscenium arch and footlights, the laptop that eventually persuaded me that I had to have it did it all by itself.

It was a purchase based on a set of seductions and manipulations that was taking place entirely in my head, rather than in physical space. And to understand how the laptop succeeded in making me want it enough to pay to take it away is to understand something about myself, and maybe also a little about the part that design has to play in the modern world. What I certainly did not have uppermost in my mind was that it would be the fifth such machine that I had owned in eight years.

By the time I reached the counter, even if I didn’t know it, I had already consigned my old computer to the electronics street market in Lagos where redundant hard drives go for organ harvesting. Yet my dead laptop was no time-expired piece of transistorized, Neolithic technology. In its prime, in the early weeks of 2004, it had presented itself as the most desirable, and most knowing piece of technology that I could ever have wanted. It was a computer that had been reduced to the aesthetic essentials. Just large enough to have a full-size keyboard, it had a distinctive, sparely elegant ratio of width to depth. The shell and the keys were all white. The catch holding down the lid blinked occasionally to show that it guarded a formidable electronic brain even when you weren’t directly engaged with it. Turn the machine over and you could spot lime-green flashes of light tracking across its belly, telling you exactly how much power the lithium battery had left. This was just another decorative flourish with a utilitarian alibi, but it tapped directly into the acquisitiveness vein.

Apple’s designers were quick to understand the need to make starting a computer for the first time as simple as locating the on switch. They have become equally skilled at visual obsolescence.

When I bought my first laptop, in the Apple store in New York in 2003, I really believed that we were going to grow old together. This was going to be an investment in my future, a possession that was so important to me that it would last a lifetime. I knew perfectly well that it was an object manufactured in tens of thousands. Yet somehow it also seemed to be as personal and engaging an acquisition as a bespoke suit. It turned out to be just one episode in Apple’s transition from producing scientific equipment to consumer not-very-durables.

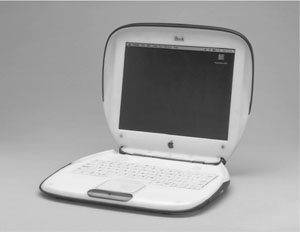

Launched in 1999, Apple’s iBook range came and went in seven years, moving from frivolous citrus fruit to serious-looking black for the MacBook.

Apple takes the view that its route to survival in a world dominated by Bill Gates’s software and Chinese hardware is to use design as a lure to turn its products into aspirational alternatives to what its competitors are selling. It expects to sell fewer machines, but it charges more for them. This involves serial seduction. The company has to make most of its customers so hungry for a new product that they will throw away the last one every two years.

The idea that I could be junking something so soon that had so recently seemed to promise so much would once have been inconceivably profligate. But this was exactly the dream of the American marketing pioneers in the 1930s. They had been determined to persuade the world to consume its way out of the Depression. The advertising pioneer Earnest Elmo Calkins coined the term ‘consumer engineering’. In Consumer Engineering: A New Technique for Prosperity, published in 1932, he suggested that ‘Goods fall into two classes: those which we use, such as motor cars, and safety razors, and those which we use up, such as toothpaste, or soda biscuits. Consumer engineering must see to it that we use up the kind of goods we now merely use.’ Apple has made it happen, just at the moment that the world is beginning to understand that there are limits to its natural resources. It has given the relentless cycle of consumption a fashionable gloss, cynically endorsed by hipsters in black jeans and black T-shirts, rather than corporate suits.

The immediate predecessor of the all-white Apple that I used to own was a semi-transparent, citrus-tinted jelly mould that established Jonathan Ive’s name as the Harley Earl of the information age. Earl was the Detroit car designer responsible for elevating tail fins in the 1950s higher and higher every season. He was the creative master of chrome. Ive, the British-born designer who has become as much a part of the Apple identity as Steve Jobs, has done the same with polycarbonate.

My new laptop was an impulse buy, but not that much of one. I knew that I wanted, though I can’t really say needed, a new machine, because the white one, just two years old, had already lost the use of its screen once. Fixing it took an astounding six weeks while Apple sent it to Amsterdam for a new motherboard. If the same thing had happened again it would have cost 60 per cent of the price of buying a new machine, and what came back would have been notably underequipped in comparison with the latest model in the Apple catalogue. I could also still remember that I had been forced to replace two successive keyboards because the letters had rubbed away within weeks, leaving the machine even more minimal than I had bargained for. And so I was in a frame of mind to open my wallet.

At Heathrow, there were two Apple models to choose from. The first was all white, like my last one. The other was the matt black option. Even though its slightly higher specification made it more expensive, I knew as soon as I saw it that I would end up buying it. The black version looked sleek, technocratic and composed. The purist white one had seemed equally alluring when I bought it, but the black MacBook now seemed so quiet, so dignified and chaste by comparison. The keys are squares with tightly radiused corners, sunk into a tray delicately eroded from the rest of the machine. The effect is of a skilfully carved block of solid, strangely warm, black marble, rather than a lid on top of a box of electronic components.

Black has been used over the years by many other design-conscious manufacturers to suggest seriousness, but it was a new colour for Apple. It is no coincidence that black is the colour of weapons: the embodiment of design shorn of the sell factor. Black is a non-colour, used for scientific instruments that rely on precision rather than fashion to appeal to customers. To have no colour implies that you are doing would-be purchasers the honour of taking them seriously enough not to try fobbing them off with tinsel. Of course this is precisely the most effective kind of seduction. And in the end black too becomes an empty signal, a sign devoid of substance.

No sooner had my new laptop come out of the box than it was clear that, while Apple’s design team, credited on the back of the instruction manual for creating this prodigy, had been clever, they had not been clever enough. They had managed the impressive trick of concealing a preloaded digital camera in the screen. It’s an arrangement that offers the memorable conjuring trick, as you go through the on-line registration process, of suddenly presenting you with your own image blinking back. But the design team at Cupertino had not addressed a technically less demanding issue with the same concentration.

While the machine is black, the cables are white. And so is the transformer, a visually intrusive rectangular box. As is the equally intrusive power plug. There is nothing about this lack of colour coordination that makes the computer work any less fluently, and yet I could feel my sense of disappointment rising as I unwrapped my purchase. How could this portal to the future have such shaky, inconsistent foundations? It felt like discovering Al Gore at the wheel of a Hummer.

What is it about consistency that seems to bestow the authority of logic, rigour and calculation? The origins of the aesthetic vocabulary of the MacBook come at just a few steps removed from the spirit of the Bauhaus that sanctified the geometry of the cube, the sphere and the cone. For the latest generation of its products Apple has borrowed a formal uniform that suggests modernism, integrity and high-minded seriousness (as opposed to the playfulness of all that citrus-fruit-coloured plastic it used to sell). Yet an essential part of that uniform is consistency. Apple couldn’t manage to do something as obvious as match the laptop and the cables, casting doubt on the integrity of the whole conception. A tree has consistency: the outline of its silhouette, the shape of a leaf, the rings on its trunk, the shape of its roots are all formed by the same DNA; and they are all of a piece. And at some level we look for man-made objects to reflect, or mimic, this quality. When they are revealed not to have it, we are disappointed.

Disappointing in a different way is Apple’s introduction of a magnetic latch connecting the machine to its power cable. It certainly stops you from inadvertently bringing the machine crashing to the floor. If you trip over the cable, it comes away with no more than the lightest pressure. But it also means that the power cord and transformer from the previous model – accessories that cost a far from negligible £100 as a separately purchased item when I left the first ones behind in a Venetian hotel room – are now utterly redundant.

Even worse, I already knew what the impact of my actually possessing this highly desirable, and desired, object would have on that svelte surface. The very first time it came out of its foamed plastic wrapping, my fingerprints would start to burn indelible marks into its infinitely vulnerable finishes. The trackpad would start to fill up with a film of grease that, as time went on, would take on the quality of a miniature duck pond. Electrostatic buildup would coat the screen with hair and dandruff. The designers, so ingenious and skilful in so many ways, were evidently still unwilling to acknowledge the imperfections of the human body when it comes into contact with the digital world. However, for true believers, there is a way to protect a MacBook. You can buy a film to wrap the machine in a whole-body condom to insulate it from all human contact.

Laptops are by no means the only consumer objects to be betrayed by their owners. Simply by using them, we can destroy almost all the things that we persuaded ourselves to love. When it was new, the metal-coated plastic body of my mobile phone from Nokia served to suggest that it was the last word in technology. Within a few months, under the constant pressure of my restless fingers, it turned into an unsightly lump of dumb polycarbonate, apparently scarred by the most scabrous of skin diseases as the metallic finish flaked away to reveal grey plastic under the polished surface. And, while its physical shape suggested a genuine attempt to create an object with which you might want to share your waking hours, other aspects of its performance are less engaging. The way that you have to negotiate the sequence of screen-based transactions and controls to operate its camera, or reach the Internet, is as awkward as attempting to use its keypad while wearing welder’s gloves.

The idea that our possessions reflect the passing of time is hardly a new concept. The traces of life as it is lived once seemed to add authority to an object, like those battered old black Nikons that Vietnam-era war photographers lugged around the killing fields of South East Asia, the shiny logo taped over to avoid the attention of snipers, the heavy brass body showing through the chipped black paint. These were objects to be treated with a certain respect. They were the product of craftsmen, ingenious mechanical contrivances that, at the press of a button, would lift the mirror that allowed you to see through the lens. These were objects with the sheer physical presence to reflect their intelligence and their value. They would last and last, delivering the performance promised by the skill with which opticians had ground their lenses, and the care with which the metallic blades that defined their shutter apertures had been designed. These are not qualities that diminish with the years.

Possessions that stayed with us for decades could be understood as mirroring our own experiences of time passing. Now our relationship with new possessions seems so much emptier. The allure of the product is created and sold on the basis of a look that does not survive physical contact. The bloom of attraction wilts so rapidly that passion is spent almost as soon as the sale is consummated. Desire fades long before an object grows old. Product design has come to resemble a form of plastic surgery, something like a Botox injection to the forehead, suppressing frown lines to create a brief illusion of beauty. It’s only the SIM cards embedded in our phones that have the ability to learn from us, to mark our friendships and our routines through the numbers that we record on them and to make meaningful patterns out of them.

Nikon started making its F series single-lens reflex cameras in 1959. The black body signalled that it was aimed at professionals.

But these, like our Google records, can be the source of well-justified paranoia as much as of comfort.

There is an effective, emotionally manipulative advertising campaign for one particular Swiss watch company whose pitch is that you never actually own one of its products: you just look after it for the next generation. It is an insight into the class-consciousness that is another way to understand the language of objects. Alan Clark’s diaries record an acid description of his fellow Conservative minister Michael Heseltine as looking like the kind of man who had to buy his own furniture. The suggestion was that it was only the vulgar, or the socially unfortunate, who would wish to do anything so crass as to buy a new dining table rather than inherit one. (Curiously, it was Clark’s father, the art historian and former director of the National Gallery Kenneth Clark, who was responsible for Civilisation, the television series and accompanying book that provoked John Berger to riposte with Ways of Seeing.)

While the watch campaign does successfully suggest a certain aura around a product, it does not challenge the essentially fleeting and ever more transient nature of our relationship with our possessions. Until the end of the 1980s, a camera was designed to last a lifetime. A telephone was leased from the government, and built to withstand industrial use. A typewriter was once something that would keep a writer company for an entire career. I still have my father’s portable. Its laminated-cardboard base has come unglued, spilling out from under its black-fabric-covered plywood box. Its keys have rusted together, the bell is stuck, and the tattered ribbon is worn through with multiple imprints from the lower-case e. From a practical point of view it is entirely useless. But I still can’t bear to throw it out, even though I know that someday whoever clears out my own house will face the same dilemma that I did. To discard even a useless object that I don’t look at from one year to the next is somehow to discard part of a life. But to keep it unused is to experience silent reproach every time you open the cupboard door. The same reproach is projected by a wall full of unread books. And once read they ask, quietly at first, but then more and more insistently, will we ever read them again?

So many product categories have not just been transformed, they have been entirely eliminated. We have lived through a period that, like the great dinosaur extinctions, has wiped out the beasts that roamed the landscape of the first industrial age. And, in the wake of the extinctions, the evolutionary process has accelerated wildly out of control. Those industrial objects that have survived have a life cycle measured in months, rather than decades. Each new generation is superseded so fast that there is never time to develop a relationship between owner and object.

Just a few of these useless objects re-enter the economic cycle as part of the curious ecology of collecting. But collecting is in itself a very special kind of fetish, perhaps one that is best understood as an attempt to roll back the passing of time. It might also be an attempt to defy the threat of mortality. To collect a sequence of objects is, for a moment at least, to have imposed some sense of order on a universe that doesn’t have any.

Objects are the way in which we measure out the passing of our lives. They are what we use to define ourselves, to signal who we are, and who we are not. Sometimes it is jewellery that takes on this role, at other times it is the furniture that we use in our homes, or the personal possessions that we carry with us, or the clothes that we wear.