PENGUIN BOOKS

FIASCO

Thomas E. Ricks is the Washington Post’s senior Pentagon correspondent. Until the end of 1999 he had covered the US military for the Wall Street Journal, where he was a reporter for seventeen years. He has reported on US military activities in Somalia, Haiti, Korea, Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Kuwait, Turkey, Afghanistan and Iraq. This book is based on his reporting in Washington and Iraq and on a steady stream of e-mails to and from soldiers at all levels serving in the field. Thomas E. Ricks has been a member of two teams that won Pulitzer Prizes for national reporting. He has lived in Afghanistan and Hong Kong and is the author of Making the Corps and A Soldier’s Duty.

THE AMERICAN MILITARY ADVENTURE IN IRAQ

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Penguin Press, a member of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2006

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2006

Published in Penguin Books with a new Preface 2007

Published with a Postscript 2007

2

Copyright © Thomas E. Ricks, 2006, 2007

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Excerpt from Meet the Press, program of February 8, 2004 © 2006 NBC Universal, Ins.

For the war dead

Know your enemy, know yourself,

One hundred battles, one hundred victories.

SUN TZU, ancient Chinese military strategist,

as quoted in Jeffrey Race’s War Comes to Long An

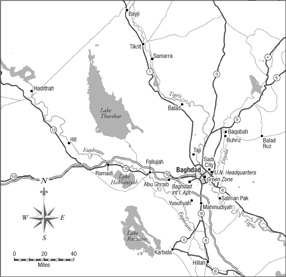

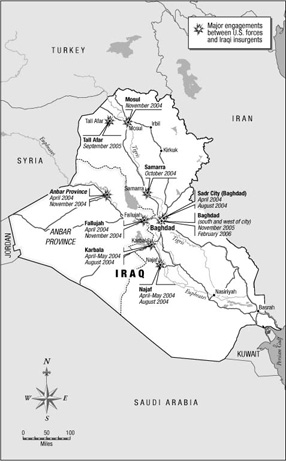

The Sunni “Triangle”: Heart of the Insurgency

Cast of Characters

Acronyms & Contractions

PART I

CONTAINMENT

1. A Bad Ending

2. Containment and Its Discontents

3. This Changes Everything: The Aftermath of 9/11

4. The War of Words

5. The Run-up

6. The Silence of the Lambs

PART II

INTO IRAQ

7. Winning a Battle

8. How to Create an Insurgency (I)

9. How to Create an Insurgency (II)

10. The CPA: “ Can’t Produce Anything”

11. Getting Tough

12. The Descent into Abuse

PART III

THE LONG TERM

13. “The Army of the Euphrates” Takes Stock

14. The Marine Corps Files a Dissent

15. The Surprise

16. The Price Paid

17. The Corrections

18. Turnover

19. Too Little, Too Late?

Afterword: Betting Against History

Postscript: April 2007

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

President George W. Bush

Vice President Richard B. Cheney

I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff and national security adviser

National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice

Secretary of State Colin L. Powell

Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage

CIA Director George Tenet

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld

Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz

Under Secretary for Policy Douglas Feith

Lawrence Di Rita, chief Pentagon spokesman

Air Force Gen. Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Army Lt. Gen. George Casey, director of the Joint Staff; later replaced Sanchez in Iraq

Marine Lt. Gen. Gregory Newbold, director of operations, the Joint Staff

Gen. Eric Shinseki, chief of staff of the U.S. Army

Richard Perle, chairman, Defense Policy Board

Ret. Marine Col. Gary Anderson, consultant to Wolfowitz

Army Gen. Tommy R. Franks, commander; retired mid-2003

Army Lt. Gen. John Abizaid, deputy commander; promoted to replace Franks

Air Force Maj. Gen. Victor Renuart, director of operations

Army Col. John Agoglia, deputy chief of plans

Gregory Hooker, senior intelligence analyst for Iraq

Army Lt. Gen. David McKiernan, commander, Coalition Forces Land Component Command (CFLCC), the ground component of the invasion force

Army Col. Kevin Benson, chief planner at CFLCC

Ret. Army Lt. Gen. Jay Garner, chief of the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, first senior U.S. civilian official in Iraq

Amb. L. Paul “Jerry” Bremer III, chief, Coalition Provisional Authority; replaced Garner

Ret. Army Lt. Gen. Joseph Kellogg, Jr., deputy to Bremer

Army Col. Paul Hughes, strategic adviser

Maj. Gen. Paul Eaton, first chief of training for Iraqi army

Marine Col. T. X. Hammes, staff, Iraqi security forces training program

Keith Mines, CPA representative in al Anbar province

Army Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, senior U.S. commander

Army Brig. Gen. Barbara Fast, senior intelligence officer for Sanchez

Ret. Army Col. Stuart Herrington, consultant to Fast

Army Maj. Gen. David Petraeus, commander, 101st Airborne Division, later returned to oversee the training of Iraqi forces

Col. Joe Anderson, a brigade commander in the 101st Airborne

Maj. Isaiah Wilson, first served as an Army historian, later as strategist for Petraeus

Army Maj. Gen. Charles Swannack, Jr., commander, 82nd Airborne Division

Col. Arnold Bray, commander of a brigade of the 82nd Airborne

Army Maj. Gen. Raymond Odierno, commander, 4th Infantry Division

Army Col. David Hogg, a brigade commander in 4th ID

Army Lt. Col. Christopher Holshek, commander of a civil affairs unit attached to Hogg’s brigade

Army Lt. Col. Steve Russell, commander of an infantry battalion in the 4th ID

Army Lt. Col. Nathan Sassaman, another of Odierno’s battalion commanders

Army Lt. Col. Allen West, commander of a 4th ID artillery battalion

Army Lt. Col. David Poirier, commander of MP battalion attached to 4th ID

Army Col. Teddy Spain, commander of U.S. military police forces in Baghdad

Army Capt. Lesley Kipling, communications officer on Spain’s staff

Army Brig. Gen. Martin Dempsey, commander, 1st Armored Division

Army Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, commander of U.S. military detention operations

Army Col. David Teeples, commander, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment

Maj. Gen. James Mattis, commander, 1st Marine Division

Army Col. Alan King, civil affairs officer, 3rd Infantry Division; later a tribal affairs specialist at CPA

David Kay, head, Iraq Survey Group, U.S. government organization searching for weapons of mass destruction

Ahmed Chalabi, leader of the Iraqi National Congress, an exile political group

Amb. John Negroponte, replaced Bremer

Amb. Zalmay Khalilzad, replaced Negroponte

Gen. Casey, promoted and replaced Sanchez

Kalev Sepp, adviser to Casey on counterinsurgency

Army Maj. Gen. John Batiste, commander 1st Infantry Division

Army Capt. Oscar Estrada, civil affairs officer attached to 1st ID in Baqubah

Army Col. H. R. McMaster, commander, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment

Col. Clarke Lethin, chief of operations, 1st Mari ne Division

Col. John Toolan, commander, 1st Marine Regiment

Retired Marine Gen. Anthony Zinni, former chief, U.S. Central Command

Rep. Ike Skelton of Missouri, senior Democrat, House Armed Services Committee

Patrick Clawson, deputy director, Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Judith Miller, national security reporter, New York Times

Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, Shiite leader and Iraq’s most important political figure

Moqtadr al-Sadr, nationalist Shiite cleric

AAR |

After Action Reviews |

AC-130 |

Attack-Cargo-130 (transport aircraft fitted with weapons) |

ACLU |

American Civil Liberties Union |

ACR |

Armored Calvary Regiment |

AD |

Armored Division |

AGM |

Air-to-Ground Missile |

AH |

Attack Helicopter |

AID |

Agency for International Development |

AIM |

Air Intercept Missile |

AMRAAM |

Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile |

AO |

Area of Operation |

AWOL |

Absent With-Out Leave |

BCT/DIV |

Brigade Combat Team / Division |

BDE |

Brigade (sic) (1,500 to 3,000 soldiers with mixed specialties) |

CA |

Civil Affairs |

CALL |

Center for Army Lessons Learned |

CAP |

Combined Action Platoon |

casevac |

Casualty Evacuation |

Centcom |

Central Command |

CFLCC |

Coalition Force Land Component Command |

CG |

Commanding General |

CIA |

Central Intelligence Agency |

CID |

Criminal Investigation Division |

CinC |

Commander in Chief |

CJTF-7 |

Combined Joint Task Force - 7 |

CMOC |

Civil Military Operations Center |

CNN |

Cable News Network |

COIN |

COunter INsurgency |

CPA |

Coalition Provisional Authority |

CRS |

Congressional Research Service |

CSIS |

Center for Strategic and International Studies |

CTC |

Combat Training Center |

DEPSECDEF |

Deputy Secretary of Defense |

DIA |

Defense Intelligence Agency |

DoD |

Department of Defense |

EPW |

Enemy Prisoners of War |

FID |

Foreign Internal Defense |

FIF |

Free Iraqi Fighters |

FM |

Field Manual |

FOB |

Forward Operating Base |

FRE |

Former Regime Elements |

FSE |

Fire Support Element |

GAO |

Government Accounting Office (old name) |

GAO |

General Accountability Office (new name) |

GOP |

Grand Old Party |

GWOT |

Global War on Terror |

H & I |

Harassment and Interdiction |

HUMINT |

Human Intelligence |

IBAS |

Individual Body Armor System |

ICDC |

Iraqi Civil Defense Corps |

ICE |

Interrogation Control Element |

ID |

Infantry Division |

IED |

Improvised Explosive Device |

IFC |

Intelligence Fusion Center |

INC |

Iraqi National Congress |

ISC |

Intelligence Systems Command |

ISF |

Iraqi Security Force |

ISG |

Iraq Survey Group |

ISST |

Iraqi Stabilization Study Team |

JDAM |

Joint Direct Attack Munition |

JPOTF |

Joint Psychological Operations Task Force |

JTF |

Joint Task Force |

LoC’s |

Lines of Communication |

M-240 |

Military [rifle] -240 (11 kg. or 24 lbs.) |

M-249 |

Military [rifle] -249 [SAW] (7 kg. or 15 lbs.) |

M-4 |

Military [rifle] -4 (3 kg. or 6½ lbs.) |

MEF |

Marine Expeditionary Force |

MET |

Mobile Exploitation Team |

MI |

Military Intelligence |

MNF |

Multi-National Force |

MP |

Military Police |

MPRI |

Military Professional Resources Incorporated |

MRE |

Meal, Ready to Eat |

MSR |

Main Supply Routes |

NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

NCO |

Non-Commissioned Officer |

NIA |

New Iraqi Army |

NIC |

New Iraqi Corps |

NIE |

National Intelligence Estimate |

Noforn |

Not to be seen by foreign governments |

NSC |

National Security Council |

NTC |

National Training Center |

OH |

Observation Helicopter |

OIF |

Operation Iraqi Freedom |

ORHA |

Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance |

OSD |

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

PBXIH-135 |

Polymer Bonded eXplosive, Insensitive High explosive-135 |

PE-4 |

Plastic Explosive -4 |

PFC |

Private First Class |

PGM/PGW |

Precision Guided Munitions or Precision Guided Weapons |

PM |

Prime Minister |

PSD |

Personal Security Details |

PUC |

Person Under Control |

RIP/TOA |

Relief In Place / Transfer Of Authority |

ROE |

Rules Of Engagement |

ROTC |

Recruit Officers’ Training Corps |

RPG |

Rocket Propelled Grenade |

SASO |

Security (Stability) And Support Operations |

SAW |

Squad Automatic Weapon (M-249) |

SCIRI |

Supreme Council of Islamic Revolution in Iraq |

SEAL |

SEa, Air Land commandos |

SF |

Special Forces |

SGCC |

Strategic Guidance for Combatant Commanders |

Signit |

Signal Intercept Intelligence |

SIPRNET |

Secret (formerly Secure) Internet Protocol Router NETwork |

sitrep |

Situation report |

SOF |

Special Operations Forces |

SOP’s |

Standard Operating Procedures |

SSI |

Strategic Studies Institute |

SVTC |

Secure Video TeleConference |

TCP |

Traffic Control Point |

TF |

Task Force |

TFIH ICE |

Task Force Iron Horse Interrogation Control Element |

THI |

Tactical Human Intelligence |

TOA |

Transfer Of Authority |

TPFDL |

Time-Phased Force Deployment List |

TTP |

Tactical Techniques and Procedures |

UH-60 |

Utility Helicopter-60, also known as a Black Hawk |

UN |

United Nations |

UPI |

United Press International |

VFW |

Veterans of Foreign Wars |

WMD |

Weapons of Mass Destruction |

Acronym list compiled by Bill Nye, the Science Guy | |

President George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003 ultimately may come to be seen as one of the most profligate actions in the history of American foreign policy. The consequences of his choice won’t be clear for decades, but it already is abundantly apparent in mid-2006 that the U.S. government went to war in Iraq with scant solid international support and on the basis of incorrect information—about weapons of mass destruction and a supposed nexus between Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda’s terrorism—and then occupied the country negligently. Thousands of U.S. troops and an untold number of Iraqis have died. Hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent, many of them squandered. Democracy may yet come to Iraq and the region, but so too may civil war or a regional conflagration, which in turn could lead to spiraling oil prices and a global economic shock.

This book’s subtitle terms the U.S. effort in Iraq an adventure in the critical sense of adventurism—that is, with the view that the U.S.-led invasion was launched recklessly, with a flawed plan for war and a worse approach to occupation. Spooked by its own false conclusions about the threat, the Bush administration hurried its diplomacy, short-circuited its war planning, and assembled an agonizingly incompetent occupation. None of this was inevitable. It was made possible only through the intellectual acrobatics of simultaneously “worst-casing” the threat presented by Iraq while “best-casing” the subsequent cost and difficulty of occupying the country.

How the U.S. government could launch a preemptive war based on false premises is the subject of the first, relatively short part of this book. Blame must lie foremost with President Bush himself, but his incompetence and arrogance are only part of the story. It takes more than one person to make a mess as big as Iraq. That is, Bush could only take such a careless action because of a series of failures in the American system. Major lapses occurred within the national security bureaucracy, from a weak National Security Council (NSC) to an overweening Pentagon and a confused intelligence apparatus. Larger failures of oversight also occurred in the political system, most notably in Congress, and in the inability of the media to find and present alternate sources of information about Iraq and the threat it did or didn’t present to the United States. It is a tragedy in which every major player contributed to the errors, but in which the heroes tend to be anonymous and relatively powerless—the front-line American soldier doing his best in a difficult situation, the Iraqi civilian trying to care for a family amid chaos and violence. They are the people who pay every day with blood and tears for the failures of high officials and powerful institutions.

The run-up to the war is particularly significant because it also laid the shaky foundation for the derelict occupation that followed, and that constitutes the major subject of this book. While the Bush administration—and especially Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, and L. Paul Bremer III—bear much of the responsibility for the mishandling of the occupation in 2003 and early 2004, blame also must rest with the leadership of the U.S. military, who didn’t prepare the U.S. Army for the challenge it faced, and then wasted a year by using counterproductive tactics that were employed in unprofessional ignorance of the basic tenets of counter-insurgency warfare.

The 2003 U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq can’t be viewed in isolation. The chain of events began more than a decade earlier with the botched close of the 1991 Gulf War and then it continued in the U.S. effort to contain Saddam Hussein in the years that followed. “I don’t think you can understand how OIF”— the abbreviation for Operation Iraqi Freedom, the U.S. military’s term for the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq—“without understanding the end of the ’91 war, especially the distrust of Americans” that resulted, said Army Reserve Maj. Michael Eisenstadt, an intelligence officer who in civilian life is an expert on Middle Eastern security issues.

The seeds of the second president Bush’s decision to invade were planted by the unfinished nature of the 1991 war, in which the U.S. military expelled Iraq from Kuwait but ended the fighting prematurely and sloppily, without due consideration by the first president Bush and his advisers of what end state they wished to achieve. In February 1991, President Bush gave speeches that encouraged Iraqis “to take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein the dictator to step aside.” U.S. Air Force aircraft dropped leaflets on fielded Iraqi units urging them to rebel. On March 1, Iraqi army units in Basra began to do just that.

But when the Shiites of cities in the south rose up, U.S. forces stood by, their guns silent. It was Saddam Hussein who continued to fight. He didn’t feel defeated, and in a sense, really wasn’t. Rather, in the face of the U.S. counterattack into Kuwait, Saddam simply had withdrawn from that front to launch fierce internal offensives against the Shiites in the south of Iraq in early March and then, a few weeks later, against the Kurds in the north when they also rose up. An estimated twenty thousand Shiites died in the aborted uprising. Tens of thousands of Kurds fled their homes and crossed into the mountains of Turkey, where they began to die of exposure.

The U.S. government made three key mistakes in handling the end of the 1991 war. It encouraged the Shiites and Kurds to rebel, but didn’t support them. Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, in the euphoria of the war’s end, approved an exception to the no-fly rule to permit Iraqi helicopter flights—and Iraqi military helicopters were promptly used to shoot up the streets of the southern cities. Army Capt. Brian McNerney commanded an artillery battery during the 1991 war. “When the Iraqi helicopters started coming out, firing on the Iraqis, that’s when we knew it was bullshit,” he recalled fifteen years later, when he was serving as a lieutenant colonel in Balad, Iraq. “It was very painful. I was thinking, ‘Something is really wrong.’ We were sitting in a swamp and it began to feel lousy.”

Second, the U.S. government assumed that Saddam’s regime was so damaged that his fall was inevitable. “We were disappointed that Saddam’s defeat did not break his hold on power, as … we had come to expect,” the first president Bush and his national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, wrote in their 1998 joint memoir, A World Transformed.

Third, the U.S. military didn’t undercut the core of Saddam Hussein’s power. Much of his army, especially elite Republican Guard units, were allowed to leave Kuwait relatively untouched. Army Col. Douglas Macgregor, who fought in one of the 1991 conflict’s crucial battles, later called the outcome a “hollow” victory. “Despite the overwhelming force President George H. W. Bush provided, Desert Storm’s most important objective, the destruction of the Republican Guard corps, was not accomplished,” he wrote years later. “Instead, perhaps as many as 80,000 Iraqi Republican Guards, along with hundreds of tanks, armored fighting vehicles, and armed helicopters escaped to mercilessly crush uprisings across Iraq with a ruthlessness not seen since Stalin.”

Having incited a rebellion against Saddam Hussein, the U.S. government stood by while the rebels were slaughtered. This failure would haunt the U.S. occupation twelve years later, when U.S. commanders were met not with cordial welcomes in the south but with cold distrust. In retrospect, Macgregor concluded, the 1991 war amounted to a “strategic defeat” for the United States.

The most senior official in the first Bush administration urging that more be done in the spring of 1991 to help the rebellious Shiites was Paul Wolfowitz, then the under secretary of defense for policy. Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, Joint Chiefs chairman Colin Powell, and National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft disagreed—and so thousands of Shiites were killed as U.S. troops sat not many miles away. This is one reason that many neoconservatives would later view Powell not as the moral paragon many Americans do but rather as someone willing to sit on his hands as Iraqis (and later, Bosnians) were killed on his watch.

Back then Powell was more often than not an ally of Cheney, who then was an unquestioned member of the hard-nosed realist school of foreign policy. “I was not an enthusiast about getting U.S. forces and going into Iraq,” Cheney later said. “We were there in the southern part of Iraq to the extent we needed to be there to defeat his forces and to get him out of Kuwait, but the idea of going into Baghdad, for example, or trying to topple the regime wasn’t anything I was enthusiastic about. I felt there was a real danger here that you would get bogged down in a long drawn-out conflict, that this was a dangerous, difficult part of the world.” Sounding like a determined foreign policy pragmatist, Cheney said that Americans needed to accept that “Saddam is just one more irritant, but there’s a long list of irritants in that part of the world.” To actually invade Iraq, he said, “I don’t think it would have been worth it.”

Likewise, Schwarzkopf would write in his 1992 autobiography, “I am certain that had we taken all of Iraq, we would have been like the dinosaur in the tar pit— we would still be there, and we, not the United Nations, would be bearing the costs of that occupation.”

Wolfowitz, for his part, penned an essay on the 1991 war two years later that listed the errors committed in its termination. “With hindsight it does seem like a mistake to have announced, even before the war was over, that we would not go to Baghdad, or to give Saddam the reassurance of the dignified cease-fire ceremony at Safwan,” he wrote in 1993. “Even at the time it seemed unwise to allow Iraq to fly its helicopters, and all the more so to continue allowing them to do so when it became clear that their main objective was to slaughter Kurds in the North and Shia in the South.” He pointed the finger at unnamed members of that Bush administration—“some U.S. government officials at the time”—who seemed to believe that a Shia-dominated Iraq would be an unacceptable outcome. And, he added, it was “clearly a mistake” not to have created a demilitarized zone in the south that would have been off-limits to Saddam’s forces and maintained steady pressure on him. Finally, he cast some ominous aspersions on the motivations of unnamed senior U.S. military leaders—presumably Powell and Schwarzkopf. The failure to better protect the Kurds and Shiites, he charged, “in no small part reflected a miscalculation by some of our military commanders that a rapid disengagement was essential to preserve the luster of victory, and to avoid getting stuck with postwar objectives that would prevent us from ever disengaging.”

Wolfowitz seemed at this point to be determined that if he ever again got the chance to deal with Iraq policy, he would not defer to such military judgments about the perceived need to avoid getting stuck in Iraq. A decade later he would play a crucial role in the second Bush administration’s drive to war, and this book will return repeatedly to examine his statements and actions. It is unusual for so much attention to be focused on a second-level official of subcabinet rank, but Wolfowitz was destined to play an unusually central role on Iraq policy. Andrew Bacevich, a Boston University foreign policy expert, is better placed than most to understand Wolfowitz, having first served a full career in the Army, and then taught at Johns Hopkins University’s school of international affairs while Wolfowitz was its dean. “More than any of the other dramatis personae in contemporary Washington, Wolfowitz embodies the central convictions to which the United States in the age of Bush subscribes,” Bacevich wrote in 2005. He singled out “in particular, an extraordinary certainty in the righteousness of American actions married to an extraordinary confidence in the efficacy of American arms.”

There was one bright point for Wolfowitz in the muddled outcome of the 1991 war: the U.S.-led relief operation in northern Iraq. As it celebrated its swift triumph, the Bush administration grew increasingly embarrassed at seeing Saddam Hussein’s relentless assault on the Kurds drive hordes of refugees into the snowy mountains along the Turkish-Iraqi border. The United States responded with a hastily improvised relief operation that gradually grew into a major effort, bringing tens of thousands of Kurds down from the mountains, and at first feeding and sheltering them, and later bringing them home. Largely conducted out of public view, Operation Provide Comfort was historically significant in several ways. It was the U.S. military’s first major humanitarian relief operation after the Cold War, and it brought home the point that with the Soviet rivalry gone, it would be far easier to use U.S. forces overseas, even in sensitive areas on or near former Eastern Bloc territory. It involved moving some Marine Corps forces hundreds of miles inland in the Mideast, far from their traditional coastal areas of operation—a precursor of the way the Marines would be used in Afghanistan a decade later. It employed unmanned aerial vehicles to gather intelligence. In an other wave of the future for the U.S. military establishment, it was extremely joint—that is, involving the Army, Marine Corps, Air Force, Navy, Special Operations troops, and allied forces. But most significantly, it was the first major long-term U.S. military operation on Iraqi soil. And in that way it would come to provide Wolfowitz with a notion of how U.S. policy in Iraq might be redeemed after the messy end of the 1991 war. In retrospect, Provide Comfort also becomes striking because it brought together so many American military men who later would play a role in the U.S. occupation of Iraq in 2003.

Provide Comfort began somewhat haphazardly, without clear strategic goals. It was initiated as an effort simply to keep Iraqi Kurds alive in the mountains, and so at first was seen just as a matter of air-dropping supplies for about ten days to stranded refugees. Next came a plan to build tent camps to house those people. But United Nations officials counseled strongly against setting up refugee camps in Turkey for fear they would become like the Palestinian camps in Lebanon that never went away. So U.S. forces first tried to create a space back in Iraq where the refugees could go, and ultimately decided simply to push back the Iraqi military sufficiently to permit the Kurds to return to their homes.

“And we carved out that area in the north,” recalled Anthony Zinni, then a Marine brigadier general who was chief of staff of Provide Comfort. Once that last step had been taken, he said, it became clear that “we were saddling ourselves with an open-ended commitment to protect them in that environment.”

Wolfowitz flew out to northern Iraq to see the operation. “We were pushing the Iraqis real hard,” then Army Lt. Gen. Jay Garner, the commander of the operation, would recall. The leading edge of the U.S. push was a light infantry battalion commanded by an unusual Arabic-speaking lieutenant colonel named John Abizaid, who in mid-2003 would become the commander of U.S. military operations in the Mideast. Abizaid was fighting what he would later call a “dynamic ‘war’ of maneuver.” He was operating aggressively but generally without shooting to carve out a safe area for the Kurds by moving around Iraqi army outposts. He also had the advantage of having U.S. Air Force warplanes circling overhead, ready to attack. Wary of having American troops behind them, with routes of retreat cut off by the planes overhead, the Iraqi forces would then fall back and yield control of territory. “We moved our ground and air forces around the Iraqis in such a way that they could fight or leave—and they left,” Abizaid said later.

American troops were pushing farther and farther south into Iraq. Alarms went off in Washington when officials at the State Department and National Security Council learned just how far south U.S. forces had thrust. In the words of the Army’s official history of Provide Comfort, “They expressed concern that the operation was getting out of hand.” In the words of Gen. Garner, looking back, “The State Department went berserk.” Orders soon arrived from the Pentagon to pull Abizaid’s battalion back to the town of Dahuk.

Zinni recalled that Wolfowitz was interested in seeing how this nervy mission was being conducted. With Garner, the two met briefly at an airfield built for Saddam Hussein at Sirsenk in far northern Iraq. How was the U.S. military operating? Wolfowitz asked. Well, Zinni explained, this Lt. Col. Abizaid is pushing out the Iraqi forces, and we’ve got more and more space here inside Iraq for the Kurds, and we’ve kind of created a “security zone,” or enclave, of some thirty-six hundred square miles.

“I started giving the brief and he really, really got into it,” recalled Zinni. “This was capturing him in some way, this was turning some lights on in his head. He was very interested in it. He was very excited about what we were doing there, in a way that I didn’t quite understand.” Zinni was puzzled. He had thought of the effort as a humanitarian mission—worth doing but without much political meaning. Wolfowitz saw it differently. “It struck me that he saw more in this than was there,” Zinni said. Carving out parts of Iraq for anti-Saddam Iraqis would become a pet idea of Wolfowitz’s in the coming years.

That meeting in Sirsenk would be one of the few times that Zinni and Wolfowitz would meet. But over the next fourteen years the two men would become the yin and yang of American policy on Iraq, with one working near the top of the U.S. military establishment while the other would be a sharp critic of the policy the first was implementing. Wolfowitz departed the Pentagon not long after his review of Provide Comfort, when the first Bush administration left office, and returned to academia.

Zinni went fairly quickly from being chief of staff in northern Iraq to deputy commander at Central Command, and then to the top job in that headquarters, overseeing U.S. military operations in Iraq and the surrounding region, from the Horn of Africa to Central Asia. In his command his main task was overseeing the containment of Iraq. In that capacity, he would be “kind of a groundbreaker for Marine four stars,” showing that a Marine could handle the job of being a “CinC” (commander in chief), or regional military commander, an Air Force general recalled. Other Marines had held those top slots, but until Zinni none had really distinguished himself in handling strategic issues.

Wolfowitz, by contrast, spent the 1990s in opposition. His path intertwined briefly with Zinni’s in the 2000 presidential election campaign, when both endorsed the Bush-Cheney ticket, though for very different reasons. After a year, Zinni would go into opposition against the Bush administration’s drive toward war with Iraq, while Wolfowitz would became one of the architects of that war.

They are very different men: Zinni is a Marine’s Marine who still speaks in the accents of working-class Philadelphia, while Wolfowitz is a soft-spoken Ivy League political scientist, the son of an Ivy League mathematician. Yet both men are bright and articulate and utterly sincere. Retired Col. Gary Anderson, who knew Zinni in the Marines and later consulted with Wolfowitz on Iraq policy, said it was this very similarity between the two men that so divided them. “They both believe in their bones what they are saying,” he observed. “Neither one is in any way disingenuous.”

Former deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage, who has worked closely with both and who has been an ideological ally of Wolfowitz but a close friend of Zinni, when asked to compare the two, said, “They have more similarities than differences.” Both are smart and tenacious, and both have strong interests in the Muslim world, from the Mideast to Indonesia—the latter a country in which both have done some work. “The main difference,” Armitage continued, “is that Tony Zinni has been to war, and he’s been to war a lot. So he understands what it is to ask a man to lose a limb for his country.”

Wolfowitz later would say that “realists” such as Zinni did not understand that their policies were prodding the Mideast toward terrorism. If you liked 9/11, he would say after that event, just keep up policies such as the containment of Iraq. Zinni, for his part, would come to view Wolfowitz as a dangerous idealist who knew little about Iraq and had spent no real time on the ground there. Zinni would warn that Wolfowitz’s advocacy of toppling Saddam Hussein through supporting Iraqi rebels was a dangerous and naive approach whose consequences hadn’t been adequately considered. Largely unnoticed by most Americans during the 1990s, these contrasting views amounted to a prototype of the debate that would later occur over the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq.

For over a decade after the 1991 war, it was the policy associated with Gen. Zinni that prevailed, even through the first year of the presidency of George W. Bush. The aim of the U.S. government, generally in its words and certainly in its actions, was containment of Iraq: ringing Saddam Hussein with military forces, building up ground facilities in Kuwait, running intelligence operations in Kurdish areas, flying warplanes over much of his territory, and periodically pummeling Iraqi military and intelligence facilities with missiles and bombs. The Saddam Must Go school associated with Paul Wolfowitz was a dissident minority voice, generally disdained by those holding power in the U.S. government.

Had all the steps that became part of the containment policy over the course of 1991 and 1992 been taken at once, they might have delivered a culminating blow to Saddam’s regime, especially if combined with a few other moves, such as seizing southern Iraq’s oil fields and turning them over to rebel forces, or making them part of larger demilitarized zones. Rather, seemingly as a result of inattention at the top of the U.S. government, a series of more limited steps were taken, like slowly heating a warm bath, and Saddam Hussein’s regime found ways to live with them. In April 1991 a no-fly zone was created in the north to protect the Kurds through a U.S. declaration that Iraqi aircraft couldn’t operate in the area. Some sixteen months later a similar zone was established to aid the battered Shiites of the south, with U.S. warplanes flying out of Saudi Arabia and from carriers in the Persian Gulf. None of the other possible steps was taken.

Looking back, Zinni said, “We were piecemealing things without the coherence of a strategy. I’m not saying that the piecemealing things when it came about weren’t necessary or didn’t make sense, but they needed to be reviewed, and we needed some sort of strategic context back here to put them all inside of.” It was a problem he would try to address when he became chief of Central Command in 1997.

But overall, he thought, the policy worked. “We contained Saddam,” he said. “We watched his military shrink to less than half its size from the beginning of the Gulf War until the time I left command, not only shrinking in size, but dealing with obsolete equipment, ill-trained troops, dissatisfaction in the ranks, a lot of absenteeism. We didn’t see the Iraqis as a formidable force. We saw them as a decaying force.”

Operation Northern Watch, the northern no-fly zone, was typical of U.S. military operations in and around Iraq after the 1991 war: It was small-scale, open-ended, and largely ignored by the American people. U.S. aircraft were occasionally bombing a foreign country, but that was hardly mentioned in the 2000 presidential campaign. Iraqis occasionally were killed by U.S. attacks, but not U.S. pilots.

Northern Watch was based at Incirlik Air Base, an old Cold War NATO base in south-central Turkey originally picked for its proximity to the underbelly of the Soviet Union, but now convenient for its nearness to the Middle East. A typical day at the base late in 2000 began with four F-15C fighter jets taking off, each bristling with weaponry: heat-seeking Aim-9 Sidewinder missiles near the wingtips, bigger radar-guided Aim-7 Sparrows on pylons closer in, and four even bigger AMRAAM missiles under each fuselage. Each taxied to the arming area, where their missiles were activated, and screamed down the runway, the engines sounding like giant pieces of paper being ripped.

The fighters were followed by an RC-135 Rivet Joint reconnaissance jet, a Boeing 707 laden with surveillance gear. Next came two Navy EA-6B electronic jammers, then some of the Alabama Air National Guard F-16s carrying missiles to home in on Iraqi radar. A total of eight F-16s were in the twenty-aircraft package. The final plane to take off was a big KC-10 tanker, a flying gas station that joined three others already airborne, as was an AWACS command-and-control aircraft. The package flew east toward northern Iraq, the Syrian border just twenty miles to the right of their cockpits. It took just over an hour for the American planes to travel four hundred miles to the ROZ, the restricted operating zone, over eastern Turkey, where the pilots got an aerial refueling and then turned south into Iraqi airspace.

Most patrols lasted four to eight hours, with the fighters and jammers flying over Iraq and then darting back to the ROZ to refuel two or three times, and the refuelers and command-and-control aircraft flying lazy circles over the brown mountains of southeastern Turkey, where Xenophon’s force of Greek mercenaries had retreated under fire from central Iraq in 400 B.C., the epic march that became the core of the classic ancient military memoir, Anabasis. Even nowadays some of the villages amid the deep canyons and escarpments carved by the headwaters of the Tigris River are so remote that they have no roads leading to them, just narrow pathways up the ridges.

When the day’s mission was over, the pilots gave the planes back to the mechanics, turned in their 9 millimeter pistols, and attended a debriefing. Most aviators preferred operating in the southern no-fly zone, which was three times as large as the cramped northern one. Also, the northern zone was bounded in part by Syria and Iran, unfriendly airspace in which to wander. But the ground crews preferred the northern no-fly operation, where the weather was cooler. In Saudi Arabia, recalled Chief Master Sgt. Dennis Krebs, a veteran of six no-fly tours there, “in the summer the surface temperatures on the aircraft get to 150 degrees, and you have to wear gloves” just to touch an aircraft. Also, in Turkey, unlike in Saudi Arabia, the troops were allowed off base.

By the late 1990s, containment was accepted by the U.S. military as part of the operating environment. “The key thing was how normal it got,” remembered one Air Force general. “There were bumps. But it got to be a kind of steady white noise in the background. It really was just background noise. … It was almost like our presence in the Cold War, in Germany, in the early days, when we’d fly the Berlin Corridor, and occasionally the Russians would do something to intimidate us, just like Saddam would try to do something.”

Out in the Persian Gulf, Cmdr. Jeff Huber, the operations officer aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, thought through his doubts about the no-fly mission. “Given that no-fly zones don’t make any sense in any traditional airpower context, how can we determine whether one is succeeding?” he asked. It was impossible to tally “Kurds/Shia Moslems not bombed,” he noted. He wound up giving the mission a tepid approval. “Many look at the no-fly zone this way: Yeah, it’s pretty stupid, but it beats letting international scumbags get away with anything they want and doing nothing about it.”

The overall cost of the two no-fly zones was roughly $1 billion a year. Other U.S. military operations, such as exercises in Kuwait, added another $500 million to the bill. That total of $1.5 billion a year was a bit more than what one week of occupying Iraq would cost the U.S. government in 2003-4, when the burn rate was about $60 billion a year, increasing slightly to about $70 billion in 2005.

In retrospect, one of the astonishments of the no-fly zones was that in twelve years not a single piloted U.S. aircraft was lost. Among some reflective military intelligence officers that raises the question of why not. Saddam Hussein clearly had some military capability, they noted, even if it wasn’t anywhere near what the second Bush administration later would claim he had. In retrospect, said one senior military specialist in Middle Eastern intelligence issues who is still on active duty, it appears that Saddam Hussein really didn’t want to shoot down any American aircraft. Rather, he walked a fine line in his behavior. “To my mind, it was carefully calibrated to show defiance, but not to provoke us,” this officer said. “He was doing enough to show his people he was confronting the mighty United States, but not more than that. It was all about internal consumption. If they had wanted to be more serious, even with their weakened military, they could have.”

In that sense, Saddam’s ambiguous stance on the no-fly zones paralleled what we now know to be his handling of weapons of mass destruction. He got rid of his chemical and biological stocks, but wouldn’t let international inspectors prove that he had done so, probably in order to intimidate his neighbors and citizens. Likewise, with the no-fly zones, his words were more threatening than his actions, but the U.S. government didn’t pick up that signal.

One day in 1996, Paul Wolfowitz toured Gettysburg with a group of specialists in military strategy from Johns Hopkins University’s school of international studies, where he became dean after his service under Cheney at the Pentagon. Late in the afternoon, as the sun dipped toward Seminary Ridge, Wolfowitz stood at the center of the battlefield, near the spot where the soldiers of Pickett’s charge had hit the Federal line and were thrown back by point-blank cannon blasts. Pointedly, Eliot Cohen, the Johns Hopkins professor running the tour, had Wolfowitz read aloud to the group the angry telegram that President Lincoln had drafted but never sent to the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, Gen. George Meade. Why, Lincoln wanted to ask his general, do you stop, and not pursue your enemy when you have him on the run?

Wolfowitz came to believe that the policy of containment was profoundly immoral, like standing by and trying to contain Hitler’s Germany. It was a comparison to which he would often return. It carried particular weight coming from him, as he had lost most of his Polish extended family in the Holocaust. His line survived because his father had left Poland in 1920.

He talked about the Holocaust more in terms of policy than of personal history, most notably in giving him a profound wariness of policies of containment. He told the New York Times’s Eric Schmitt that “that sense of what happened in Europe in World War II has shaped a lot of my views.” What if the West had tried to “contain” Hitler? This orientation toward Nazism would prove central to his thinking on Iraq. Again and again, he would describe Saddam Hussein and his security forces as the modern equivalent of the Gestapo—it was almost a verbal tic with him.

Some observers of Wolfowitz speculate that another lesson he took from the Holocaust is that the American people need to be pushed to do the right thing, because by the time the United States entered World War II it had been too late for millions of Jews and other victims of the Nazis. Asked about this in an interview before the war, Wolfowitz agreed, and expanded on the thought—and himself linked it to Iraq: “I think the world in general has a tendency to say, if somebody evil like Saddam is killing his own people, ‘That’s too bad, but that’s really not my business.’” That’s dangerous, he continued, because Hussein was “in a class with very few others—Stalin, Hitler, Kim Jong Il. … People of that order of evil … tend not to keep evil at home, they tend to export it in various ways and eventually it bites us.” The analogy to Nazism gave Wolfowitz a tactical advantage in that it instantly put critics on the defensive. If one was convinced that Saddam Hussein was the modern equivalent of Hitler, and his secret police the contemporary version of the Gestapo, then it was easy to see—and portray—anyone opposing his aggressive policies as the moral equivalent of Neville Chamberlain: fools at best, knaves at worst. So for years Wolfowitz prodded the American people toward war with Iraq.

After teaching political science at Yale, Wolfowitz as a diplomat helped bring democracy to South Korea and the Philippines in the 1970s and 1980s. He took away from those experiences a belief that every country is capable of becoming democratic—and that their becoming so aids the American cause. “I think democracy is a universal idea,” he would say. “And I think letting people rule themselves happens to be something that serves Americans and America’s interests.”

Wolfowitz’s bookish background also gave him an academic manner that can be disarming. There is in Wolfowitz little of the blustery Princeton frat boy towel-snapping banter on which Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld seems to thrive. His soft voice and mild manner frequently surprise those who have braced themselves for the encounter. “I actually was surprised to find, the first time I met him, that he was pretty likeable, which surprised me, because I hate him,” said Paul Arcangeli, who served as an Army officer in Iraq before being medically retired. (His loathing, he explained, is a policy matter: “I blame him for all this shit in Iraq. Even more than Rumsfeld, I blame him.” His bottom line on Wolfowitz: “Dangerously idealistic. And crack-smoking stupid.”)

But Wolfowitz’s low-key manner cloaked a tough-minded determination that ran far deeper than is common in compromise-minded Washington. One of the most important lessons of the Cold War, he wrote in the spring of 2000, was “demonstrating that your friends will be protected and taken care of, that your enemies will be punished, and that those who refuse to support you will live to regret having done so.”

In January 1998, the Project for the New American Century, an advocacy group for an interventionist Republican foreign policy, issued a letter urging President Clinton to take “regime change” in Iraq seriously. Among the eighteen signers of the letter were Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld, Armitage, future UN ambassador John Bolton, and several others who would move back into government three years later. “The policy of ‘containment’ of Saddam Hussein has been steadily eroding over the past several months,” they wrote. “Diplomacy is clearly failing … [and] removing Saddam Hussein and his regime from power … needs to become the aim of American foreign policy.” The alternative, they concluded, would be “a course of weakness and drift.”

“Containment was a very costly strategy,” Wolfowitz said years later. “It cost us billions of dollars—estimates are around $30 billion. It cost us American lives. We lost American lives in Khobar Towers”—a huge 1996 bombing in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 service members and wounded 372 others. But he also saw other costs. “In some ways the real price is much higher than that. The real price was giving Osama bin Laden his principal talking point. If you go back and read his notorious fatwah from 1998, where he called for the first time for killing Americans, his big complaint is that we have American troops on the holy soil of Saudi Arabia and that we’re bombing Iraq. That was his big recruiting device, his big claim against us.”

Wolfowitz also saw another cost, one that most Americans hadn’t noticed much: “Finally, containment did nothing for the Iraqi people.” Large parts of the Iraqi population suffered hugely under a contained Saddam, and the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq were on the route to being wiped out, he noted. “That’s what containment did for them. For those people, liberation came barely in time.”