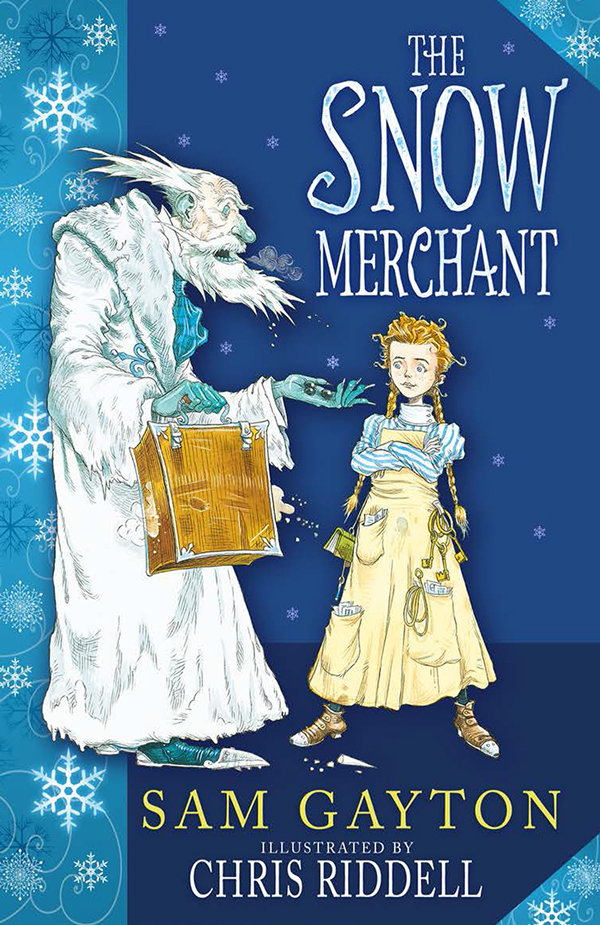

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: In the Land of Albion

1. A Stranger Arrives

2. An Invention Called Snow

3. Kicking Out the Breezes

4. One Boy Travels a Very Long Way

5. The Suitcase Opens

6. Lettie Peppercorn Brews Tea

7. The Making of the White Horse Inn

8. Follow Those Frostprints!

9. The Wind Lends a Hand

10. The Endless Inflation of Blüstav the Alchemist

Part Two: Upon the Sea

1. Shaking Out the Truth

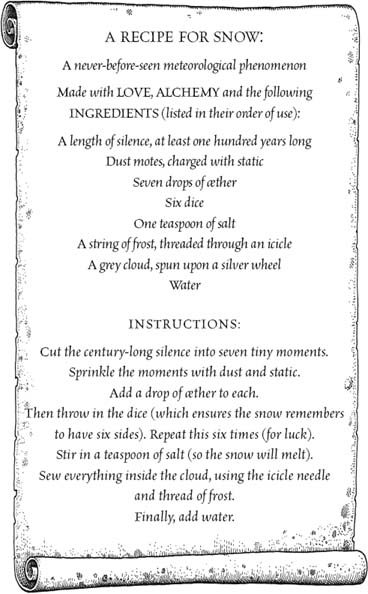

2. The Making of Snow

3. The Distant Rising Smoke

4. Four Drops of Æther

5. An Itchy Nose Saves the Day

6. Noah Grows a Blazing Pip

7. Where the Wind Blows

8. The Ship Sinks

9. A Little Imagination is Required

10. Up and Away

Part Three: Inside an Iceberg

1. Ma

2. The Making of Lettie Peppercorn

3. The Thief, the Liar, the Cheat and the Clam

4. Lettie Peppercorn Stitches the Waves

5. A Mighty BOOM Interrupts Dinner

6. Noah Will Come

7. Justice is Served

8. The Awful Loneliness Returns

9. A Top Hat Wishes to be Borrowed

10. The Great Experiment Begins

Epilogue. Once, in Baveria

Acknowledgements

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781448187515

www.randomhouse.co.uk

First published in 2011 by

ANDERSEN PRESS LIMITED

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

www.andersenpress.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

The rights of Sam Gayton and Chris Riddell to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Text copyright © Sam Gayton, 2011

Illustrations copyright © Chris Riddell, 2012

Decorative icons copyright © Tomislav Tomic, 2011

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

ISBN 978 1 78344 177 8

To Erin, who is Boss.

Praise for The Snow Merchant

‘A tale of self discovery, family and friendship . . . an inventive and accomplished debut’

Independent on Sunday

‘A delightful debut . . . full of action and invention’

The Sunday Times

‘A germ of JK and a pinch of Pullman’

TES

‘Full of fairytale and fun, which should appeal to Lemony Snicket fans’

Daily Mail

‘A quirky and very inventive debut’

Editor’s Choice, Children's Books Ireland

‘Exhilarating, entertaining and original, bursting with ideas’

Books for Keeps, Book of the Month

‘Beautifully old-fashioned storytelling [which] weaves a hugely imaginative tale of alchemy, family and snow’

The Bookseller

‘A gripping debut’

LoveReading4Kids

‘A most fantastical story, not dissimilar to Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland’

The School Librarian

Praise for Lilliput

‘Unlimited storytelling inventiveness . . . Swift himself would have approved’

Irish Times

‘A spirited and clever tribute to the original’

Daily Mail

‘Exuberant and imaginative use of language, page-turningly exciting’

Reading Zone

‘Don't miss this book. It really is something rather special’

The Bookbag

‘This magical novel with its indomitable heroine offers an enthralling experience . . . An excellent addition to this genre’

The School Librarian

‘Of bodies changed to other shapes I sing’

Ovid, Metamorphoses

ON A WINTER night so cold and dark the fires froze in their hearths, snow came to Albion. It came packed up in the suitcase of a stranger. Lettie was the first to see him.

The stranger walked up from the harbour, dragging his luggage bump bump bump over the cobbles of Barter town, searching for the sign of the White Horse Inn. He found it on Vinegar Street, swinging from the porch of a house on stilts. Up above, through the little kitchen window, Lettie the landlady watched him come.

With her telescope, she traced the long line of footprints etched behind him in muddied frost. She saw him put a hand on the ladder that led to the door and start to climb, up through the black and swirly night. The Wind was so strong it could have whisked away the fingers from his hands, and he wore no gloves. It was the coldest winter Lettie had ever known, and he was by far the coldest guest.

His teeth were blue.

His hair was white.

His fingers were blue.

The whites of his eyes were blue, and his pupils were white.

‘A man with an icicle beard,’ she whispered to Periwinkle, who had just flown inside. ‘Where will we put him? All the beds are taken.’

Periwinkle cocked his head and Lettie sighed. For a pigeon, he was a good listener but he was terrible at conversation.

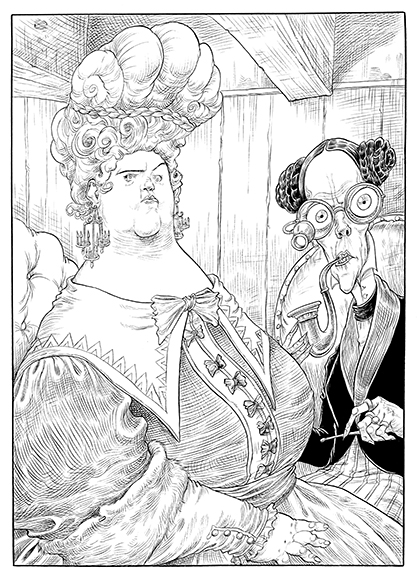

Lettie closed her telescope with a snap and dropped it in her apron pouch. She went into the tiny front room, where her two guests – a Lady from Laplönd and a Bohemian jeweller – sat in armchairs by the hearth. Their real names were signed in the guestbook, but Lettie called them the Walrus and the Goggler. The Lady was the Walrus, because she was fat with whiskers. The jeweller was the Goggler, because she did nothing but stare. They suited Lettie’s names better than their own.

‘Someone’s coming up,’ said the tiny, shrunken Goggler. She hooked her scopical glasses round her ears and flicked down the lenses to glare at the door, her eyes big as saucers.

‘He will not be having my bed,’ said the Walrus. Her wobbly lipstick pouted, her piggy eyes squinted and her treble chins shook.

Lettie had no time to answer before the door flew open. On the porch stood the man with the icicle beard.

‘I need a room,’ he said, ‘and it must be freezing!’

At once, the fire died down to embers. The Wind swept in, and before the Walrus could cover her ears, it snuffed out the ten tiny candles on her chandelier earrings.

‘Yes,’ said the stranger softly. ‘This will do nicely.’

His smile made a cracking sound, and a shard of his icicle beard fell to the floor.

Lettie stared. With jitters in her belly, she went to pick up his suitcase, but he shooed her with his hand.

‘Get away,’ he said with a scowl. ‘Far too delicate.’

‘I’m not delicate,’ she answered. ‘I’m twelve.’

‘I was talking about my merchandise,’ he snapped, nodding at the mahogany suitcase. ‘It’s very … sensitive. If it was spoilt, you wouldn’t want to buy it. And I would have come all this way for nothing.’

‘Sir,’ said Lettie. ‘I don’t know what you’re selling, but I can’t afford it.’

‘Don’t be presumptuous,’ barked the stranger. ‘I know a customer when I see one.’

The Walrus and the Goggler watched from underneath their furs.

Lettie was speechless. For a week she had heard nothing but:

‘More sugar in the tea!’

‘More blankets on the armchairs!’

‘More wood on the fire!’

Now here was someone – a frozen man with a suitcase full of mystery – telling her that she was his customer.

Lettie Peppercorn, stop your gawping and say something, she thought.

‘Welcome to the White Horse Inn, sir.’

‘Yes, yes!’ he said impatiently. ‘Now fetch the landlord before I defrost!’

Lettie rolled her eyes. New guests always made this mistake. She wiped her hands on her apron. ‘I’m the landlady.’

‘You?’ he sneered.

Lettie gave him one of her sterner looks. ‘That’s right, sir. Me. Lettie Peppercorn.’

‘Well, what about Mr Peppercorn?’

‘Da’s at the pub, if I had to take a guess. Down by the harbour, at the Clam Before the Storm, betting with the sailors.’

The stranger pursed his blue lips in irritation. ‘And Mrs Peppercorn?’

‘Well,’ said Lettie hotly. ‘If I had to take a guess, I’d say that’s none of your business.’

‘Girl, you have no idea about my business. Remember that. You’re just a customer.’

‘I’m much more than that,’ said Lettie. ‘I wash sheets, I dust shelves, I tidy up rooms and I brew a very good cup of tea.’

‘Her talents as a landlady,’ said the Walrus, ‘are satisfactory.’

‘But the decor is atrocious,’ said the Goggler, ‘and rather ugly on the eyes.’

Lettie followed the stranger’s gaze as it swept around the tiny room. The White Horse Inn was drab and bare. The pictures were gone from the walls, leaving dark squares on the wood. There was a dining table by the kitchen, two armchairs by the fire and Ma’s old pianola in the corner. There was one rug left. It was small.

‘It looks cold enough,’ he said.

‘But all our beds are full,’ said Lettie.

‘I don’t want a room for sleeping, girl. I want a room for business.’

Lettie was in half a mind to give him a lecture on good manners and send him packing. But she couldn’t. The White Horse Inn needed money. Da’s gambling already had Mr Sleech, the debt collector, knocking at the door each week. So instead of a telling-off, she gave the stranger a smile and showed him her wide, wonderful eyes: the eyes of her Ma, long gone.

‘Certainly then, sir. Bed or business, it’s all the same rate here …’ She stuck out her hand and said: ‘Three shillings a night, if you please.’

‘Three shillings is reasonable …’ began the Goggler.

‘… for an inn with more than one rug,’ finished the Walrus.

‘You can have any room you like for your business,’ said Lettie, ignoring them. Then she lowered her voice so the old ladies couldn’t hear, and added: ‘Even theirs.’

She expected him to haggle. He was a businessman, and this was the town of Barter, after all. But he just scowled and said, ‘I better get everything I need from you.’

‘You will,’ Lettie promised. ‘With a brew and a smile.’

‘Very well,’ he said. ‘We have a deal.’

Lettie had to stifle a cheer. She was so desperate for money that she would have taken two shillings. Three would cover all of Da’s debts for tonight. If she sent them to him now, he wouldn’t have to borrow from Mr Sleech, the debt collector. And that meant that Mr Sleech wouldn’t come round at midnight for the last rug.

Three cheers for the man with no manners and an icicle beard! she cried out in her head.

Lettie realised that she didn’t know his name. He hadn’t introduced himself, which was strange indeed, especially since he was a businessman and she was supposed to be his customer. She wondered if it would be rude to ask, but before she could he bent down suddenly and picked three pebbles from the black ice around his boots.

‘Here,’ he said. ‘Put out your hand.’

Lettie folded her arms instead. ‘Sir, I asked for three shillings, not stones.’

‘And I said, “Put out your hand”. So stop your pouting and do as I say, girl.’

Reluctantly, Lettie obeyed. He dropped the pebbles into her palm: one, two, three. Reaching inside his coat, he brought out a glass phial shaped like a J. It was filled with thick, silver liquid. He twisted off the cork and put a drop on each of the pebbles.

And something happened.

Something extraordinary.

The pebbles began to fizz. They jumped in Lettie’s palm like crickets.

‘Keep them in your hand!’ said the stranger.

Lettie clasped her hands together, and inside the pebbles bounced around. Then the air went pop! three times, and they fell still. A little wisp of smoke wriggled from between her fingers.

‘Finished,’ said the stranger, corking the bottle.

Lettie opened her hands.

She couldn’t help but gasp.

The old ladies in their armchairs just stared, open-mouthed.

‘Now,’ the stranger said, ‘we can get down to business.’

But Lettie couldn’t. She was rigid with shock. In her palm the pebbles were gone, and in their place were three silver shillings.

‘How did you do that?’ she whispered.

He put the bottle away inside his coat. ‘An alchemist can make anything he wants.’

Lettie clutched the coins up in her fist. That word: alchemist. She hadn’t seen an alchemist for years. Now there was one at her inn, making money from rocks and carrying a suitcase full of mystery…

The last alchemist to stay at the White Horse Inn had been Lettie’s ma. But she was gone now. She’d left three things: a note, her coat and a hole that had never been filled.

‘It’s a long time since we had an alchemist here at the White Horse Inn,’ Lettie said to him as he fiddled with the straps around his suitcase. ‘The last one vanished through the window.’

‘I shall be keeping the windows shut,’ he said without interest.

‘Did you know this inn was made with alchemy, sir? It started life as rubbish, rubbish that got mixed up in a cauldron with special alchemicals, and it all got changed and ended up a house—’

‘I’ve no time for chatter!’ he said, his temper sparking. ‘You’re to do as you’re told, or I’ll turn those shillings back into pebbles just as quick as I made them.’

Lettie scowled. ‘There’re rules for staying here,’ she said. ‘The ledger’s over there, and you’ve got to sign it. Your name, where you’re going, and what you’re carrying.’

He strode up to the book, leaving frostprints as he went, and took the quill in his hand.

‘Do you see his teeth?’ murmured the Walrus.

‘Bright blue,’ said the Goggler, filling a pipe with mint leaf. ‘And do you see that suitcase?’

‘Mahogany,’ the Walrus said. She shivered and her chandelier earrings twinkled. ‘How unusual.’

‘How interesting.’

Lettie rushed into the kitchen and took the room keys from the hook by the stove. Periwinkle fluttered on his perch, a message from Da dangling on his foot:

Nearly won the last game! Might borrow a few more shillings. Don’t worry; I’ve got a good feeling about this! Da xxx

Da always had a good feeling after a few bottles of beer.

Lettie put that thought out of her mind quickly, before more bad ones came.

‘Borrowing a few shillings?’ she murmured. ‘Not this time, you’re not!’ She turned to Periwinkle. ‘I’ve got a message for you to fly back in a bit, Peri. But now I’ve got to settle in the new guest. He’s got a temper. He’s got blue teeth too. Let me find out his name for you.’

She went back into the front room with the keys. The alchemist threw down the quill and picked up his suitcase without a word. Lettie peered at the ledger to catch his secrets. Her eyes went wide when she saw where he had signed: the red ink had run blue.

Lettie looked at the quill, then back at the page.

He hadn’t signed his name at all.

It just said Snow Merchant.

Lettie wondered. A merchant was someone with something to sell.

But what was snow?

‘WHAT’S SNOW?’ ASKED Lettie.

‘You’re my customer,’ said the Snow Merchant. ‘You’ll find out soon enough.’

There was expectation in his voice, like sparks. Lettie could tell he was excited. She could tell he was nervous.

Nervous about what? she wondered.

The Snow Merchant swung his suitcase up onto the table. Its legs creaked with the weight.

‘I’ve never seen a suitcase made of mahogany before,’ said Lettie. ‘And I see a lot of suitcases in this business.’

‘It’s bolted and buckled with lead,’ said the Snow Merchant.

‘Must be hard to carry!’ said Lettie.

‘It keeps what’s inside weighed down,’ he answered.

Lettie frowned. She had been landlady to dozens of guests, and they always brought with them one thing: luggage. There had never been a suitcase like this before. The prizefighters from Bavolga brought their leather boxing gloves, in search of new opponents; the chess-players from Yssa brought their black and white boards, looking for new moves; the perfumers from Parall brought empty boxes, to catch new smells in … Lettie even knew where the Walrus was going next with her luggage: back to Laplönd with the Goggler, to show off her new chandelier earrings, which the Goggler had made.

But what had the Snow Merchant brought with him? What was the mystery he wanted to sell to Lettie?

Suddenly the clock by the bar chimed ten, and the Snow Merchant jumped. ‘The coldest hour of the night will come soon!’ he cried in panic.

Lettie tore her eyes from the suitcase. ‘Is that bad?’ she asked.

‘It means there’s no time!’

‘No time for what?’ said the Walrus.

‘For the creation!’ he said. ‘For the creation of snow! I have to make it before I can sell it, and to make it, I need a room!’

Lettie jangled the keys. ‘Which would you like, sir?’

‘No, no!’ the Snow Merchant cried. ‘There’s no time to choose!’ He looked around. ‘This one right here will do!’

And before Lettie could stop him, he strode up to the hearth to do battle with the fire. It hissed and spat at him, as if the two were old enemies. The Snow Merchant regarded it contemptuously and then plunged a hand into his huge, black coat. He rifled away, searching for something. Lettie heard the rustle and clink of bottles as he went through each pocket.

‘Here it is!’ he cried, withdrawing a small, crooked phial with a pipette lid. He shook it in front of his eyes and watched the contents slosh inside the glass. To Lettie, it looked like liquid frost: bitter blue, cruel and cold.

‘Oh, yes,’ he said, his voice soft with menace. ‘You know this, don’t you? It’s æther, isn’t it? And it shall be the death of you.’

The ladies in their armchairs whimpered, and Lettie quaked and backed away, but she realised that the Snow Merchant wasn’t talking to any of them: he was talking to the fire. Feeling rather foolish, she looked again to the flames as they squirmed in the grate.

The Snow Merchant unscrewed the lid and Lettie’s goose bumps rose. The æther leeched the warmth from the room.

‘Quite hard to obtain,’ said the Snow Merchant. ‘And quite impossible to bottle, but nevertheless, I am a genius.’

He squeezed the pipette and it sucked up a drop of æther.

He turned to Lettie. ‘You might want to light a lamp.’

‘Why?’ she asked, trembling. ‘What does æther do?’

He laughed at her, at the fire. ‘Why, it’s an alchemical, of course. It’s what we alchemists use to change things. Every alchemical works a different change. Mammonia, for example, changes pebbles into shillings. Gastromajus, another of my potions, changes people into their last meal.’

‘And what does æther change?’ said Lettie.

‘Why, temperature!’ said the Snow Merchant, squeezing a drop of æther onto the fire. It snuffed out the flames in an instant, plunging everything into darkness and leaving a smell in the air, like the start of a storm. The ladies shrieked in their armchairs and the Snow Merchant cursed and cried out: ‘I told you to fetch a light!’

Lettie fumbled for the lamp in the kitchen and brought it out. After a while her eyes adjusted, and the Snow Merchant threw open the curtains to let in the cloudless night. In came the moonbeams. They pooled on the window ledges like wax. Everything now looked silver and expensive. The plates stacked by the pianola shone like shillings.

‘I almost prefer it like this,’ Lettie said.

‘I certainly don’t,’ said the Walrus, rising up from her armchair, her mink coat wrapped around her. She wore a powdered wig one size too big, and it wobbled over her forehead. Her diamond earrings, shaped like chandeliers, tinkled and swung. ‘I am chilled to my bones!’ she declared. ‘The least I deserve is a cup of tea! With cream and three sugars … make that five sugars.’

‘I will have peppermint,’ said the Goggler. ‘With a splash of rum.’

But Lettie wasn’t making tea. Her head was a kettle of questions.

‘Do you know what snow is?’ she asked the old ladies.

The Walrus smiled sweetly and said, ‘That is not the question you should be asking.’

‘Why?’ said Lettie.

‘And that is not the question, either,’ said the Walrus, in a higher voice.

‘What’s the question I should be asking, then?’

‘The question,’ she shrieked, ‘is, “How many times does a guest need to ask for a cup of tea before she gets one?”.’

‘Be quiet!’ said the Snow Merchant as he put drops of æther on the pianola keys. ‘You are lucky I am letting you watch my alchemy at all.’

‘Lucky?’ cried the Walrus. ‘We are stuck on this drab little island, waiting for a ship that will take us to Laplönd! That is not luck, that is torture!’

Lettie knew this already, for it had been written in the ledger. The Walrus had been all the way to Bohemia, where the Goggler had made her a special pair of chandelier earrings, and now they were on their way back to Laplönd to show them off.

The Goggler rubbed the rings on her hands. Lettie had counted at least seven on each of her fingers (they were alarmingly long, for someone so small). ‘I don’t know what is worse,’ she declared. ‘The boredom or the frostbite.’

‘The Wind is worst of all,’ sniped the Walrus. ‘The inn sways so much I feel quite queasy—’

‘I am trying to freeze this room!’ thundered the Snow Merchant, slamming the pianola lid shut. ‘Yet you insist on filling it with hot air! Sit down!’

The Walrus looked at him, outraged. But she did flop back into her armchair.

‘I want a cup of tea,’ she declared, waving a fat finger this way and that. ‘There should be tea and cake for a lady of my standing.’

‘Madam,’ said the Snow Merchant. ‘If you eat much more cake, then standing really will be an issue for you.’

‘How dare you? When we get to Laplönd, I shall be the height of fashion!’

‘But for now, madam, you are just a blob of blubber, babbling nonsense,’ said the Snow Merchant. ‘So kindly shut up, and let me work.’

Lettie clapped a hand to her mouth. Lettie Peppercorn, don’t you giggle.

The Walrus sat numb with shock at being spoken to so rudely.

The Goggler stood to her full height of one and a half metres, and fiddled with her scopical glasses so she could glare at the Snow Merchant more ferociously.

‘I am the most famous jeweller in all Bohemia!’ she announced, in a voice full of accent and arrogance. ‘The Lady is my customer, and I demand you apologise at once!’

‘Why?’ asked the Snow Merchant simply.

‘Because we are Ladies of Elegance!’ spluttered the Goggler. ‘Because we are Women of Stature! Because—’

‘I beg your pardon,’ the Snow Merchant interrupted, ‘but how can you be a woman of stature, when I mistook you earlier for a footstall? Sit down, you crinkled-up, craggy-faced crone!’

The two ladies seemed as lost for words as Lettie.

Finally, though, the Walrus recovered first from the Snow Merchant’s astonishing attack of rudeness. Her chins were trembling with fury. ‘All I am asking for is a cup of tea!’

‘My customer is too busy to make you tea,’ said the Snow Merchant.

‘I am?’ Lettie said. ‘I thought I was just standing here with my teeth chattering.’

‘Then do your job!’ he snapped. It seemed even Lettie wasn’t safe from his bitter temper.

‘Job?’ said Lettie. ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘Get rid of the draughts, girl! Every last breeze.’

LETTIE STOOD IN the front room, feeling the inn sway on its stilts and wondering how this night could get any stranger. The Snow Merchant had just asked her to get rid of the breezes, but how? Why?

‘This is an inn built on stilts,’ she said at last. ‘You can’t escape the Wind up here.’

‘Maybe that’s why your guests do nothing but moan,’ said the Snow Merchant, and he laughed at his own wit.

Lettie scowled in the dark. She loved the Wind, she envied it: it travelled the world; it went wherever it wanted, while she was stuck inside, held prisoner by her job and Ma’s last message. She looked over to the note, hanging on the wall above the door. It didn’t matter that it was dark: she knew it off by heart. Just forty-three words, but they ruled her life:

It was because of the note that Da had raised the house on stilts. Then he’d made Lettie promise on her life that she’d do everything the note asked. She had tried everything to convince him to let her leave the White Horse Inn. When she was nine, Lettie had even made herself a miniature pair of stilts, so she could walk into town without touching the ground at all. But Da had shaken his head, like always, and said it was too dangerous.

Lettie didn’t know what the danger was. She had asked Da, but he didn’t know either. When Lettie was little they had sat long into the night, trying to figure it out. But, like an impossible riddle, Ma’s words led them around in circles. ‘Let’s sleep on it,’ Da had said, when the hour got too late. ‘Maybe we’ll crack it tomorrow.’

Now, Da left Lettie to wonder about the note all on her own. ‘Trust your ma,’ was all he would say. ‘Remember your promise.’

It was a hard promise to keep, day after day, high tide after low tide, guest after guest. At least in the winter it wasn’t so bad. She had Periwinkle and the Wind to talk to. She had her telescope. But still, sometimes it made her so angry she could scream. Ma wrote a note, vanished out of the window, and that was that: all the mothering Lettie would ever get.

Lettie Peppercorn, clear your head of all this useless thinking.

And so she did. Lettie set to work, chasing out the breezes. She followed them with a tea towel, all the way back to the places where they had wriggled in, then plugged up the cracks with newspaper or Da’s old socks.

‘Be off with you,’ she told the Wind, stuffing hankies in the keyholes. ‘You’re good for keeping me company, but you’re bad for business.’

The Wind wasn’t happy. It tickled the Walrus’s feet and knocked over Da’s half-empty cup of khave. When Lettie finally shut it out completely, it whirled around, rattled the windows and tried to sneak down the chimney. She covered the hearth with newspaper. The Wind howled and the timber stilts groaned. The house lurched forward, and the ledger fell from the table.

‘You stop that right now!’ Lettie called up the fireplace, and the Wind went still and sullen.

The Snow Merchant raised both eyebrows, which made crackling sounds. ‘I’ve never seen a little girl shout down the Wind before. It never does what I say.’

Lettie shrugged. ‘That’s because you’ve got no manners. What do we do next?’

He scowled. ‘Now we let the cold come,’ he replied. ‘We let it settle deep. And you can fetch me a bucket of water from the well.’

The well.

Lettie clenched up like a fist. She was going to have to tell the whole room about her promise. Her anger churned away. She hated to say it, especially to travellers who came and went whenever they pleased. It made her feel so horrible, angry and ashamed.

‘I can’t go outside,’ she muttered. ‘Not even to the Vinegar Street well. If I climb down that ladder, I might die.’