Codependency For Dummies®, 2nd Edition

Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. The Twelve Steps are reprinted with permission of Co-Dependents Anonymous, Inc. (CoDA, Inc). Permission to reprint this material does not mean that CoDA, Inc. has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that CoDA, Inc. agrees with the views expressed herein. Co-Dependents Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women whose common purpose is to develop healthy relationships and is not affiliated with any other 12 step program. Copyright C 1998 Co-Dependents Anonymous, Incorporated and its licensors — All Rights Reserved. The Twelve Steps of CoDA as adapted by CoDA with permission of Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (“AAWS”), are reprinted with permission of AAWS and CoDA. Permission to reprint these Twelve Steps does not mean that AAWS has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that AAWS necessarily agrees with the views expressed therein. Alcoholics Anonymous is a program of recovery from alcoholism only — use or permissible adaptation of A.A.’s Twelve Steps in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after A.A., but which address other problems, or in any other non-A.A. context, does not imply otherwise.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK ARE INTENDED TO FURTHER GENERAL SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, UNDERSTANDING, AND DISCUSSION ONLY AND ARE NOT INTENDED AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON AS RECOMMENDING OR PROMOTING A SPECIFIC METHOD, DIAGNOSIS, OR TREATMENT BY PHYSICIANS FOR ANY PARTICULAR PATIENT. THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. IN VIEW OF ONGOING RESEARCH, EQUIPMENT MODIFICATIONS, CHANGES IN GOVERNMENTAL REGULATIONS, AND THE CONSTANT FLOW OF INFORMATION, THE READER IS URGED TO REVIEW AND EVALUATE THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THE PACKAGE INSERT OR INSTRUCTIONS FOR EACH MEDICINE, EQUIPMENT, OR DEVICE FOR, AMONG OTHER THINGS, ANY CHANGES IN THE INSTRUCTIONS OR INDICATION OF USAGE AND FOR ADDED WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS. READERS SHOULD CONSULT WITH A SPECIALIST WHERE APPROPRIATE. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR ANY DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM.

For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 877-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002. For technical support, please visit www.wiley.com/techsupport.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014951024

ISBN 978-1-118-98208-2 (pbk); ISBN 978-1-118- 98209-9 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118- 98210-5 (ebk)

If you’re reading this book because you wonder whether you may be codependent, you’re not alone. Some think the majority of Americans are codependent. The term codependency has been used since the 1970s. The newer perspective is that codependency applies to many more people than originally thought. Different types of people and personalities may be codependent or behave in a codependent manner. Codependence varies in degree and severity. Not all codependents are unhappy, while others live in pain or quiet desperation. Here are examples of people who may be codependent:

Codependents are attracted to codependents, so there’s little chance of having a healthy relationship. The good news is the symptoms of codependency are reversible. It requires commitment, work, and support. Even so, sometimes the symptoms can sneak up on you and affect your thinking and behavior when you least notice it. Codependency isn’t something you heal from and are forever done with, but you can one day enjoy yourself, your life, and your relationships. Should you choose to embark on recovery, you’re beginning an exciting and empowering journey. A new way of living and seeing the world opens up. I hope you decide to join me on this amazing journey.

Not all codependents are in a relationship with someone who suffers from an addiction. Whether or not you are, this book is for you as you relate to your loved one. If you’re recovering from an addiction to a substance or process, such as alcohol, eating, hoarding, shopping, working, sex, gambling — the list goes on — and are ready to work on your issues revolving around codependency, then this book is an ideal place to start. However, the focus of this book is not on overcoming those addictions, but on your relationships. (When I refer to “addict,” I mean not only a drug addict, but also a person with any type of addiction. Sometimes, I specify alcoholics.)

Although a book is linear and compartmentalized — you read a sentence or paragraph that discusses one thing at a time — people exist through four dimensions of space/time, and codependency is holographic, affecting everything in the way you live your life. It’s neither linear nor three-dimensional. Every trait affects every other. This book breaks down codependency into parts in order to discuss its various aspects, but that’s not how you experience codependency. For instance, just answering yes or no to a question is impacted by your self-esteem, values, boundaries, feelings, and reactivity — all at once. On top of that, there are things from your past or the present about which you may be unconscious and in denial. They, too, affect everything you say and do. Even when you understand all the moving variables, the process is impossible to understandably explain in a few sentences.

This book is very comprehensive and details everything you need to know about codependency in one place. It provides tools you can implement to take an active role in your recovery. I reorganized this second edition to follow the way you’d experience recovery — first understanding the definition, symptoms, and causes, and then engaging in the evolving process of changing and healing. However, feel free to jump around and read it in any order that you choose. There are cross references to other chapters that are relevant to the topic being discussed. A new chapter has been added to explain the process of working the Twelve Steps, which is an important means of recovery. An additional Part of Tens chapter for professionals is available online to help clinicians avoid codependent behavior.

There are self-discovery exercises, which are an important part of the book. If you’re a professional, feel free to copy and use these exercises with your clients. If you’re tempted to skip the exercises, you miss out on a major feature, which is included for your benefit to help you change. One strategy is to read through the book, and then go back and do the exercises at your leisure. After you do them, you can also repeat an exercise you find helpful months or years from now and will most likely acquire new knowledge about yourself. Some exercises are meant to be repeated, and like any exercise, every time you do it, you benefit.

Those new to codependency probably won’t be able to implement advice found in later chapters. If that happens, don’t be dismayed. If you begin recovery and pick up this book down the road, you may read it with different eyes and glean new insights and understanding.

Because denial operates at an unconscious level, you may not relate to it unless you read how other people experience it. Therefore, I’ve included a number of examples that are composites of clients and people I’ve known, including myself; any resemblance to a real person is coincidental, as specific details and facts have been changed. The names are made up and appear in boldface.

Not knowing your familiarity with codependency, in writing this book, I assumed you may be totally new to the concept, someone already in recovery, or a mental health professional who is seeking more information. I’ve tried to write so that nonprofessionals are able to understand all the concepts; however, some ideas are profound and written for the person who wants to comprehend the deeper psychology underlying codependency. It’s certainly not written for dummies.

What’s cool about For Dummies books is that there are icons throughout letting you know what’s really important and what you can skip. Here are the icons used in this book:

In addition to the material in the print or e-book you’re reading right now, this product also comes with some access-anywhere goodies on the web. You can access this additional free, valuable information on the Dummies website:

http://www.dummies.com/cheatsheet/codependency

http://www.dummies.com/extras/codependencyWhere you start reading depends on how much you know about codependency. If you’re just beginning to investigate codependency, begin in Part I. If you’re ready to begin recovery, I recommend that you get a journal to take notes, write about yourself, and do the many exercises that are designed to enlighten you and further your recovery.

Remember, reading is only a beginning. It opens your mind to the problem. It takes time, work, and support to overcome codependency. So read all you can, talk to other recovering codependents, and find a sponsor in a Twelve Step program or a professional coach or mental health professional to help guide you on your journey. For specific information on getting outside support and where to find it, go to Chapters 6 and 17.

Part I

In this part . . .

Chapter 1

In This Chapter

Introducing you to codependency

Introducing you to codependency

Briefing you on the history and controversies about codependency

Briefing you on the history and controversies about codependency

Facing the problem

Facing the problem

Understanding the stages of codependency and recovery

Understanding the stages of codependency and recovery

Identifying goals of recovery

Identifying goals of recovery

All relationships have their troubles. There are times when people you love the most hurt and disappoint you, and you worry when they’re suffering. Addicts obsess about their “drug” of choice, whether it’s alcohol, food, or sex. They plan and look forward to it. Codependents do that in relationships. Their lives revolve around someone else — especially those they love. Their loved ones preoccupy their thoughts, feelings, and conversations. Like jumpy rabbits, they react to everything, put aside what they need and feel, and try to control what they can’t. They hurt, and they hurt. This chapter introduces you to codependency and what it means to be codependent. It explores the goals and the healing process, called recovery.

Although mental health clinicians recognize codependency when they see it, the definition of codependency and who has it has been debated for decades. (I devote an entire chapter — Chapter 2 — to explaining what codependency is.) Experts agree that codependent patterns are passed on from one generation to another and that they can be unlearned — with help.

Therapists and counselors see people with an array of symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, addiction, or intimacy and relationships issues. Clients are hurting and often believe the cause is something outside of themselves, like their partner, a troubled child, or a job.

On closer examination, however, they (and many readers of the first edition of this book) start to see that, despite whatever else may be going on, their behavior and thinking patterns are adding to their problems — that is to say, their patterns are dysfunctional. These patterns have an addictive, compulsive quality, meaning that they take on a life of their own, despite their destructive consequences. The root problem is usually codependency.

Along with comfort and pleasure, intimate relationships especially evoke all your hopes, fears, and yearnings. You want to feel secure and be loved, appreciated, and taken care of. Dependence upon those closest to you further magnifies your emotional needs and vulnerability to being rejected, judged, and seen at your worst.

All the symptoms I outline in Chapter 3 work together to not only deprive codependents of the benefits possible in relationships, but they also create problems that wouldn’t have otherwise existed. For example, shame and low self-esteem make you insecure, anxious, and dependent upon others’ acceptance and validation. You may feel uncomfortable being yourself and be hypersensitive to perceived criticism or abandonment (even where neither exists). You may attempt to control or manipulate people to maintain a relationship and to be liked. Some codependents require repeated reassurances or are afraid to be direct and honest, which is necessary for effective communication and real intimacy.

By Darlene Lancer

Figure 1-1: Self in confusion.

All relationships require boundaries. Love is not safe without them. Yet many codependents tolerate being treated without respect, because they lack self-worth. They don’t feel entitled to compliments, to be truly loved, or to set limits. They might do more than their share at work or in a relationship to earn acceptance, but they end up feeling unappreciated, used, or resentful. In reading this book, ask yourself whether your relationships feed you or drain you.

Shame can also cause codependents to deny or discount their feelings and needs, both to themselves and in their relationships. To cope, they sometimes disregard what’s actually happening, ruminate with worry or resentment, or finally explode. Their denial and confusion about their boundaries and responsibilities to themselves and to others create problems with intimacy and communication. Instead of bringing couples closer, frequently communication is avoided, is used to manipulate, or is highly reactive, leading to escalating conflict and/or withdrawal. Nothing gets resolved. They end up feeling trapped and unhappy because their symptoms paralyze them with fear of rejection and loneliness.

The symptoms of codependency are all interwoven. They lead to painful emotions and self-sabotaging behaviors that produce negative feedback loops. This book helps you untangle and free yourself from them and create positive, healing feedback loops.

Although codependency has only relatively recently been recognized as an illness (dating from the 1970s), the characteristics were described as neurotic traits by Karen Horney 75 years ago. The term itself evolved out of family therapy with alcoholics, following the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in 1935 by Bill Wilson to help alcoholics find sobriety.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, leading neo-Freudians and humanists began focusing on the development of personality. Karen Horney, referred to as the first feminist psychoanalyst, was one of the leading proponents for self-actualization.

Horney broke with Freud on many issues and believed that children have a fundamentally good “real self,” which thrives in a healthy, empathic, and supportive environment. Natural striving to actualize their true nature can be thwarted due to poor parenting and cultural influences; however, self-awareness can go a long way to unshackle the real self from those negative influences, allowing it to flourish. Horney conceptualized a compliant personality alienated from the real self that today resembles typical traits of codependents. Some of her other personality categories may be codependent, too. Her influence is apparent in the writings of humanist psychologists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers in the mid-20th century.

Family system theories emerged from the study of cybernetics, systems theory, and systems psychology. In the mental health field, theorists and therapists were increasingly viewing mental illness in a family context. In clinics, counselors noticed that some patients improved, but when they returned to their families, their symptomatic behavior returned. The counselors deduced that the family dynamics were maintaining or even causing the illness and began focusing on family interactions.

Therapists who worked with alcoholics observed repetitive patterns among the spouses and families of the alcoholics that reinforced drinking behavior. They saw husbands and wives who reproached and tried to manage an alcoholic, unaware that they were trying to control an uncontrollable illness. The family members displayed dysfunctional characteristics and were initially referred to as co-alcoholics. From years of disappointments and submergence of their personality, they had become empty shells. Their self-esteem and despair were as low as that of the alcoholics.

Surprisingly, clinicians discovered that many of the problems in the family persisted even after the alcoholics found sobriety. They found that their spouses’ dysfunctional patterns predated the alcoholic marriage and continued into new sober relationships. They realized that the co-alcoholics had to recover independently of the person and relationship that brought them to Al-Anon, the Twelve Step program for families of alcoholics. Still later, it was observed that those patterns appeared in others who weren’t involved with an addict but had grown up in dysfunctional families (see Chapter 7). All of their findings thus validated and converged with psychoanalytic theory.

The term codependency was born in the late 1970s and by the 1980s was being applied to addicts and their relatives, family members of someone with chronic mental or physical illness, and caregiving professionals.

Soon after AA was founded, Bill Wilson’s wife, Lois, saw that the spouses, mostly wives at that time, needed support. She started holding meetings in members’ homes. These meetings expanded to include all relatives and friends of alcoholics, and Al-Anon was born. In the 1950s, a main office was established in New York City to coordinate groups that had spread nationwide and today worldwide.

Eventually in 1986, the self-help program Co-Dependents Anonymous (referred to as CoDA) was founded by two therapists, Ken and Mary, who both grew up in dysfunctional, abusive families and had histories of addiction. CoDA was also modeled on the Twelve Steps of AA. Unlike Al-Anon, membership wasn’t linked to having a relationship with an alcoholic. The only requirement, as stated in its preamble, “is a desire for healthy and loving relationships.” The meeting of the First National Conference on Co-dependency was held in 1989.

As the awareness of addiction grew, more habits and compulsions began being characterized as addictions, and increasingly people seemed to have codependent traits that compromised their relationships, both among addicts and those close to them. Family systems author and theorist Virginia Satir commented that of the 10,000 families she’d studied, 96 percent exhibited codependent thoughts and behaviors. By the late 1980s, former psychotherapist Anne Wilson Schaef called America an addictive society in her 1988 book, When Society Becomes an Addict (HarperOne).

The controversy around codependency is divided into two camps — for and against. At one end are mental health professionals who advocate that codependency is a widespread and treatable disease. On the other is an array of critics of codependency, who argue that it’s merely a social or cultural phenomenon, is over-diagnosed, or is an aspect of relationships that doesn’t need to change. Those in the “against” camp state that it’s natural to need and depend upon others. They claim that you only really thrive in an intimate relationship and believe that the codependency movement has hurt people and relationships by encouraging too much independence and a false-sense of self-sufficiency, which can pose health risks associated with isolation.

Other naysayers disparage the construct of codependency as being merely an outgrowth of Western ideals of individualism and independence, which have harmed people by diminishing their need for connection to others. Feminists also criticized the concept of codependency as sexist and pejorative against women, stating that women are traditionally nurturers and historically have been in a nondominant role due to economic, political, and cultural reasons. Investment in their relationships and partner isn’t a disorder, but has been necessary for self-preservation. Still others quarrel with Twelve Step programs in general, saying that they promote dependency on a group and a victim mentality.

Committees have lobbied for codependency to be recognized as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, which would allow insurance coverage for treatment. A major obstacle is the lack of consensus about the definition of codependency and diagnostic criteria. For insurance purposes, clinicians usually diagnose patients with anxiety or depression, which are symptoms of codependency.

Maybe you’re wondering whether you’re codependent. It may be hard to tell at first, because, unless you’re already in recovery, denial is a symptom of codependency, as I explain in Chapter 4. Whether or not you identify as codependent, you can still benefit from alleviating any symptoms you recognize. You will function better in your life. Recovery helps you to be authentic, feel good about yourself, and have more honest, open, and intimate relationships.

If you’re codependent, generally symptoms show up to some extent in all your relationships and in intimate ones to a greater degree. Or codependency may affect your interaction with only one person — a spouse or romantic partner, a parent, sibling, or child, or someone at work. Codependency may not affect you as much at work if you’ve had effective role models or learned interpersonal skills that help you manage. Maybe you weren’t having a problem until a particular relationship, boss, or work environment triggered you. One explanation may be that the parent has a difficult personality or the child has special needs, and the couple has adjusted to their roles and to one another, but avoids intimacy.

By Darlene Lancer

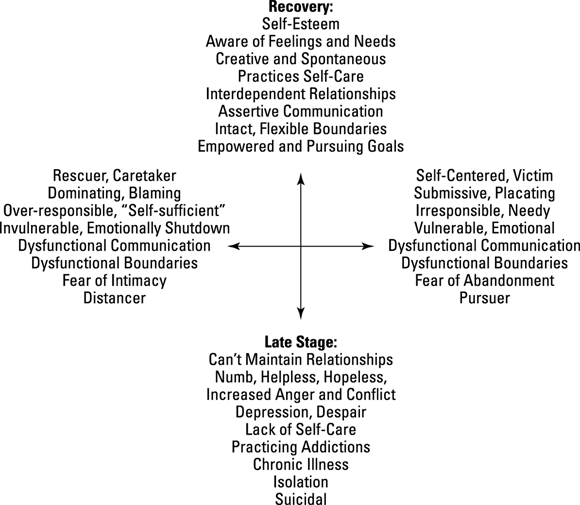

Figure 1-2: The continuum of codependency.

Both the disease and recovery exist on a scale represented by the vertical vector in Figure 1-2. Codependent behavior and symptoms improve with recovery, described at the top, but if you don’t take steps to change, they become worse in the late stage, indicated at the bottom.