INTRODUCTION

DEVELOPMENTAL DETAILS

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

ARMAMENT

POWERPLANT

COLOUR SCHEMES

RADAR

ORGANISATION OF THE S-BOOTWAFFE

OPERATIONAL USE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

COLOUR PLATE COMMENTARY

Germany had been involved in the construction of high-quality and extremely fast motorboats since before the end of the nineteenth century, with one of the most influential manufacturers being the firm of Otto Lürssen. In 1908, a boat built by this firm, and powered by a Daimler engine, had reached speeds of 50 knots. Being built purely for speed, however, such boats were far too fragile for combat use. The first fast motorboats built for the Kaiserliche Marine were unable to be fitted out as torpedo boats due to a general shortage of torpedoes and were used instead as sub-chasers (UZ or U-Boot Zerstörer).

By the outbreak of the First World War, the German Navy had also experimented with remote-controlled boats. These were termed FL-boats (Fernlenkboote) and were effectively remote-controlled bombs, their bows packed with high explosives, intended to be steered directly at their targets – initially British ‘Monitors’ operating off the Flanders coast. A similar idea was resurrected in World War Two with the appearance of the Linsen motorboats used by the Kleinkampfmittel verbände. These boats had their bows packed with explosives and were driven straight at their targets, the operator diving overboard at the last moment, to be picked up later by a control boat.

True motor torpedo boats made their appearance with the L-boats, later renamed LM-boats (Luftschiffmotorenboote), so-called because they were powered by the same engines used in the Zeppelin airships. The manufacture of these boats was once again pioneered by the firm of Otto Lürssen in Vegesack, though other firms were soon involved in their manufacture, particularly the Naglo firm in Zeuthen near Berlin, Oertz of Hamburg and Roland of Hemelingen. The first four boats, LM-1 to LM-4, were armed with only a 3.7cm gun. From LM-5 to LM-20, each boat was fitted with a single bow torpedo tube, backed up with machine gun armament. LM-21 to LM-33 were planned but not completed.

A classic image of the E-boat, moving at speed, its bows raised high and causing a substantial bow wave to form. These three boats, moving in line astern, are from 1 Schnellbootsflotille and are of the late-war S-100 type with armoured bridge. The forward 2cm flak gun can just be seen at the bows.

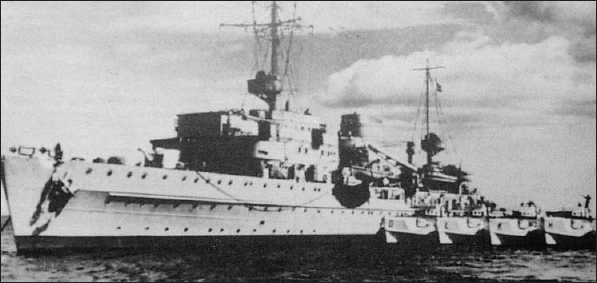

The E-boat tender Carl Peters with boats of the S-Bootslehr division moored alongside. The tender itself was not a particularly large ship, and gives some indication of the diminutive size of the typical E-boat. Note that these boats from the training division have their code letters painted on the bow.

The designations of the last boats planned to appear in World War I were based on a combination of the name of the shipyard wherein they were built and the type of powerplant. Thus, Lüsi 1 and 2 were to be built by Lürssen and have motors built by Siemens/Deutz, Köro 1 and 2 were to have Körting engines and were to be built by Roland, and Juno 1 to 4 were to have had Junkers engines and be built by Oertz. They were all intended to be much more powerful boats, with twin bow torpedo tubes as well as a 2cm cannon. In the event none were ever completed.

The fast motor torpedo boats were used principally in the Baltic and off the coast of Flanders. Although no major successes against enemy shipping are recorded, these boats had at least shown that such small, fast, torpedo-armed craft had considerable potential.

After World War I, the terms of the Versailles Treaty totally banned Germany from possessing submarines and severely restricted possession of surface vessels. Though Germany was left with a small fleet of torpedo boats, these were not fast motor torpedo boats, but larger, slower, steam-driven boats displacing around 900 tons and were almost the size of a small destroyer.

The new German navy that was reborn from the ashes of the old Kaiserliche Marine was small. However, due the loss of almost her entire navy with the scuttling of the High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow and the dismantling of her U-boat Fleet, Germany was forced to start anew, and the ships the new Reichsmarine and its successor, the Kriegsmarine built, were fast, modern ships that had been developed to take full advantage of the latest technologies.

Despite this, the Kriegsmarine, even at its most powerful, could never have hoped to match long-established and numerically superior fleets such as the British. Major surface units such as the Bismarck and Tirpitz may well have been more than a match for any single equivalent ship in any enemy navy at the time they were launched, but as they would inevitably be met with an overwhelming superiority of numbers when they did put to sea, for example what happened to the Bismarck, their moment of glory would be fleeting before they inevitably succumbed.

For many in Germany, it seemed that the only way of countering the might of the Royal Navy was to build substantial numbers of small, torpedo-bearing craft. In submarines, this was to result in a large number of the small Type II being constructed, and for the surface fleet, the concept found its outlet in the development of the fast motor torpedo boat.

Once again it was to be the smaller vessels of the navy (and predominantly the U-boats) that would come nearest to inflicting defeat on Germany’s enemies. The E-boat fleet may have been relatively small, but its achievements were significant, ranking it amongst the most successful and cost-effective elements of the Kriegsmarine in World War II.

Note: The term E-boat is generally accepted to have been a British term derived from the designation Enemy Boat. As this term is far more widely recognised than the correct term S-boat (from the German Schnellboot or fast boat), it will be used throughout this work except where German terminology is used, such as in flotilla titles, etc. In effect, the terms E-boat, E-boats, and S-boot are all interchangeable.

As with the U-boats, design and development of the E-boats was carried out in secret, behind the guise of several commercial ‘front’ businesses. One such was the civilian firm of Navis GmbH in Berlin, actually run by naval officer Kapitän zur See Lohmann, who arranged for the ‘private’ purchase of several partially completed LM-boats by civilians acting as front-men for the navy, to prevent their being taken over by the Allies. Yacht manufacturing concerns and boating clubs such as Travemünder Yachthafen AG, were also set up, the latter being tasked with development of fast motor torpedo boats under Korvettenkapitän Beierle, whilst giving the appearance of simply producing civilian sporting craft.

These boats were used in the mid-1920s, albeit unarmed, on secret training exercises with larger surface warships to prove the concept of the fast, manoeuvrable, torpedo-carrying boat. The potential for such boats was not lost on the Reichsmarine. Once again, the Lürssen firm was heavily involved, as were others such as Abeking and Rasmussen in Bremen and the Kasparwerft in Travemünde. With their intended use hidden behind the designation UZ(s) U-Boot Zerstörer (schnell) or fast sub-chaser, development continued.

A later high forecastle model moving at speed, its bows raised out of the water to show the black anti-fouling paint used on the lower hull. This model is of the same basic type as those which later had the armoured bridge fitted, as evidenced by the 2cm gun just visible, projecting from its tub on the foredeck. However, it still has the earlier style of open bridge over the wheelhouse. Note that the colour scheme used on most E-boats was a grey so pale that it almost appears white on monochrome photographs.

One of the main questions taxing the minds of those intent on perfecting the design of the ideal fast motor torpedo boat was the delivery of the main weapon – the torpedo. Three main methods of discharging the torpedo were considered:

Bow Launch What was to become the standard method, with torpedo tubes mounted on the bow of the boat, launching the torpedo nose first towards the target. Though this may seem obvious today, other, more extreme methods were considered.

Stern Launch–Tail First This rather dangerous-sounding method saw torpedoes being launched tail first (i.e. nose pointing in the same direction as the boat), from tubes at the stern, requiring the boat to make a tight turn to port or starboard to avoid its own torpedoes.

Stern Launch–Nose First This required the boat to turn 180 degrees away from the target and launch torpedoes towards the enemy whilst it made off in the opposite direction. This method had some merit and was actually used on some very small E-boats.

Not surprisingly, the method selected was the bow-mounted tube.

The highly experienced Lürssen firm became involved again in the manufacture of motor torpedo boats for the Reichsmarine on an official basis in 1930, with the 52 ton UZ(s)-16 (eventually to be renumbered as S-1). The boat soon proved itself in tests and was the basis for all future E-boat development. The basic E-boat design changed little over the course of its development. In all, there were 13 identifiable models, which could reasonably be considered under three main categories, early-, mid-and late-war types. Many of the changes were subtle and are not immediately apparent even when studying photographs of the vessels.

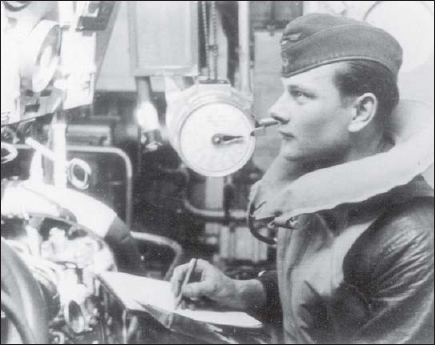

The ‘Chief’ (in peaked cap) and one of his engine room crew in the diesel motor room of an E-boat. Note the black leather protective clothing worn. This was very similar to that used by U-boat crews and indeed by engine room crews on many surface ships.

S-1