Preface for students: a guide to studying human evolution

Acknowledgments

PART 1 THE FRAMEWORK OF HUMAN EVOLUTION

Chapter 1 The growth of the evolutionary perspective

Our place in nature

Establishing the link between humans and apes: historical views

Human evolution as narrative and as explanation

Chapter 2 The principles of evolutionary theory

The fundamentals of evolutionary theory

Modern evolutionary theory: the development of Neo-Darwinism and the power of natural selection

Chapter 3 Pattern and process in evolution

From micro- to macroevolution: debates in modern evolutionary theory

The physical context of evolution

Extinction and patterns of evolution

Chapter 4 The geological context

Dating methods

The science of burial

Chapter 5 The systematic context

Systematics

Molecular systematics

Chapter 6 Human evolution in comparative perspective

Primate heritage

The comparative perspective

Bodies, size, and shape

Bodies, brains, and energy

Chapter 7 Reconstructing behavior

Bodies, behavior, and social structure

Non-human models of early hominin behavior

Jaws and teeth

PART 2 EARLY HOMININ EVOLUTION

Chapter 8 Apes, hominins, and humans: morphology, molecules, and fossils

Morphology and molecules: a history of conflict

Evolution of the catarrhines: the context of hominin origin

Chapter 9 Searching for the first hominins

The earliest hominins

Bipedalism

Chapter 10 The apelike hominins

The australopithecines

Chapter 11 Origins of Homo

The genus Homo

Hominin relationships

Chapter 12 Behavior and evolution of early hominins

Early tool technologies

The pattern of early hominin evolution

Chapter 13 Africa and beyond: the evolution of Homo

Evolutionary patterns

New technologies

Hunter or scavenger?

PART 3 LATER HOMININ EVOLUTION

Chapter 14 The origin of modern humans: background and fossil evidence

Background for the evolution of modern humans

Competing hypotheses for modern human origins

Chronological evidence

The question of regional continuity

The place of Neanderthals in human evolution

Chapter 15 The origin of modern humans: genetic evidence

The impact of molecular evolutionary genetics

Recent developments

Chapter 16 The origin of modern humans: archeology, behavior, and evolutionary process

Archeological evidence

Regional patterns in the archeology

Toward an integrated model of modern human origins

Chapter 17 Evolution of the brain, intelligence, and culture

Encephalization

Cultural evolution

Chapter 18 Language and symbolism

The evolution of language

Art in prehistory

Chapter 19 New worlds, old worlds

Completing colonization

The first villagers

The human evolutionary heritage

References

Index

We would like to thank the following people who helped in the development of this book. Many people read all or sections of it, and helped to improve it: Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, Henry Harpending, Katerina Harvati, Jim Kidder, John Relethford, Karen Rosenberg, Karen Schmidt, Liza Shapiro, Robin Smith, Shelley Smith, Christian Tryon, Christina Turner, Russell Tuttle, and Carol Ward. William McGrew was especially helpful in correcting errors and discussing the larger issues of human evolution with great enthusiasm. Nathan Brown of Blackwell Publishing should be especially thanked for his persistence and patience, both of which in their different ways were appreciated, and for allowing us to interpret his word “urgent” in our own idiosyncratic way. Fiona Sewell also provided much assistance in the production of the text and figures. R. F. would especially like to thank Marta Mirazón Lahr, for her tolerance of this distraction away from other things that were equally pressing, as well as, as always, endless expert advice and guidance.

As the train doors open at many stations on the London Underground, a disem-bodied voice can be heard saying “Mind the gap” to warn passengers that there is a larger than usual step between the train and the platform. This helpful announcement can act as a rather surprising motto for anyone about to embark on a course on human evolution.

KEY QUESTION How should evolutionary biology approach the problem of human uniqueness versus the continuities inherent in the evolutionary process?

The reason for this is very simple. If one asks the average person to come up with terms they associate with evolution, then after “survival of the fittest,” “progress” (of which more later), and “missing link,” another one that is highly likely to figure is “continuity.” Evolution is a continuous process, and so provides a link between all organisms in such a way as to place them all on a continuum, from the simplest single-cell organism to the most complex social mammal. Through evolution, plants and animals slide endlessly from one form to another. Continuity is therefore a major part of nature. However, the same average person, if asked whether there is a continuity between humans and other animals, is likely to answer no. Certainly there are many things that humans and other animals share, from their basic genetic code to the broad body plan of the vertebrate skeleton, but the gulf between humans and, say, chimpanzees, no matter how smart the latter appear to be, remains large, and to some unbridgeable. Humans are the species of Shakespeare and Dante, of Galileo and Einstein, of Wallace and Darwin, of Michelangelo and Picasso, of Beethoven and Bach; or alternatively, the species of Hitler and Stalin. No chimpanzee can come close to these sorts of achievements.

In the contrast between the continuity of evolution and the uniqueness of humans lies the challenge and interest of human evolution. It is the paradox that lies at the heart of the discipline – how is it possible to simultaneously “mind the gap” that exists between humans and other species and be true to the continuous nature of the evolutionary process? It is that challenge that has fueled much of the research into human evolution.

FIGURE 1.1 Ptolemy’s universe: Before the Copernican revolution in the sixteenth century, scholars’ views of the universe were based on the ideas of Aristotle as elaborated by Ptolemy. The Earth was seen as the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets fixed in concentric crystalline spheres circling it.

The problem of the gap has long been recognized. In 1859 Charles Darwin published his epoch-making book, The Origin of Species, in which he provided an account of how evolution worked, and how science might explain the patterns of life without recourse to supernatural beings and processes. While Darwin made little or no reference to humans, but confined himself to ordinary plants and animals, the implications were plain to see. Within four years his friend and supporter, Thomas Henry Huxley, published one of the first books on human evolution, Evidences as to Man’s Place in Nature. The book was based on evidence from comparative anatomy among apes and humans, embryology, and fossils of early humans (few were available at the time). Huxley’s conclusion – that humans have a close evolutionary relationship with the great apes, particularly the African apes – was a key element in a revolution in the history of Western philosophy: humans were to be seen as being a part of nature, no longer as apart from nature – hence the title of Huxley’s book. What both Darwin and Huxley, as well as many other scientists of that time, were keen to demonstrate was the continuity between humans and the rest of the biological world, and that all were the product of the same evolutionary processes. In other words, evolution underpinned the continuity of nature, including humans.1

Although Huxley was committed to the idea of the evolution of Homo sapiens from some type of ancestral ape, he nevertheless recognized that humans were a very special kind of animal. In his book he wrote:

No one is more strongly convinced than I am of the vastness of the gulf between … man and the brutes, for, he alone possesses the marvelous endowment of intelligible and rational speech [and] … stands raised upon it as on a mountain top, far above the level of his humble fellows, and transfigured from his grosser nature by reflecting, here and there, a ray from the infinite source of truth.2

It is worth noting that the problem of continuity versus breaks in the chain of life is one that both continues through to the present day and existed in pre-evolutionary scientific thought. The reason for this goes back to the intellectual upheavals of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The revolution wrought by Darwin’s work was, in fact, the second of two such intellectual upheavals within the history of Western philosophy.3 The first revolution occurred three centuries earlier, when Nicolaus Copernicus replaced the geocentric model of the universe with a heliocentric model (Fig. 1.1). Although the Copernican revolution deposed humans from being the very center of all of God’s creation and transformed them into the occupants of a small planet orbiting in a vast universe, they nevertheless remained the pinnacle of God’s works. From the sixteenth through the mid-nineteenth centuries, those who studied humans and nature as a whole were coming close to the wonder of those works (Fig. 1.2).

This pursuit – known as natural philosophy – positioned science and religion in close harmony. What linked them was the notion of design.4,5 The living world could be seen to be admirably efficient and well organized, with each organism playing a role for which it was well suited. This was taken as evidence for a remarkable design, and consequently as evidence for a designer – in other words, the hand of God.

In addition to design, a second feature of God’s created world was a virtual continuum of form, from the lowest to the highest, with humans being near the very top, just a little lower than the angels. This continuum – known as the Great Chain of Being – was not a statement of dynamic relationships between organisms, reflecting historical connections and evolutionary derivations (Fig. 1.3). This focus on continuity, echoed in evolutionary ideas, was in fact one of the platforms on which Darwin built his theory. The difference between the pre-evolutionary idea of the Great Chain of Being and the later concept of an evolving lineage, though, is that the former was fixed. According to Stephen Jay Gould, the essence of the Chain of Being is the fixed positions of biological organisms in an ascending hierarchy.6

FIGURE 1.2 Two great intellectual revolutions: In the mid-sixteenth century the Polish mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric rather than a geocentric view of the universe. “The Earth is not the center of all things celestial,” he said, “but instead is one of several planets circling a sun, which is one of many suns in the universe.” Three centuries later, in 1859, Charles Darwin further changed people’s view of themselves, arguing that humans were a part of nature, not apart from nature.

FIGURE 1.3 The Chain of Being: Both pre-evolutionary and early Darwinian perceptions of the relationship among living creatures involved the idea of a Chain of Being, or scala naturae, which implied a progressive development of greater complexity and change in the direction of humanity.

However, powerful though the Chain of Being theory was, it faced problems – as it happens, exactly the same problems as Huxley recognized, namely the gaps that occurred between certain parts of this Great Chain. One such discontinuity appeared between the world of plants and the world of animals. Another separated humans and apes.

Knowing that the gap between apes and humans should be filled, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scientists tended to exaggerate the humanness of the apes while overstating the simianness of some of the “lower” races. For instance, some apes were “known” to walk upright, to carry off humans for slaves, and even to produce offspring after mating with humans. By the same token, some humans were “known” to be brutal savages, equipped with neither culture nor language. Basically, the natural philosophers were using the tales of sailors and the myths of the ancient world to fill in the gaps in their model scheme of creation.

This perception of the natural world inevitably became encompassed within the formal classification system, which was developed by Carolus Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century. In his Systema Naturae, published first in 1736 and finally in 1758, Linnaeus included not only Homo sapiens – the species to which we all belong – but also the little-known Homo troglodytes, which was said to be active only at night and to speak in hisses, and the even rarer Homo caudatus, which was known to possess a tail7 (Fig. 1.4).

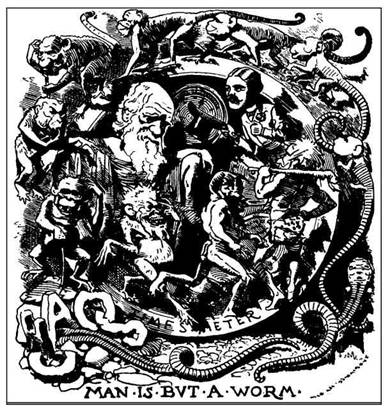

In one sense the theory of evolution provided a solution to the difficulties faced by the natural philosophers, namely a better understanding of the dynamic nature of the links between the entities on the Great Chain of Being. The dynamism of evolution did not really remove the Great Chain, but added a new dimension to it – that of progress, which in turn provided an explanation for the hierarchy that many saw in both the natural world and humanity. For instance, humans were still regarded as being “above” other animals and endowed with special qualities – those of intelligence, spirituality, and moral judgment. And the gradation from “lower” races to “higher” races that had been part of the Great Chain of Being was now explained by the process of evolution.

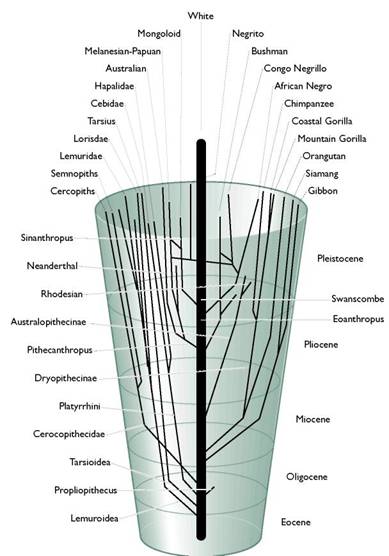

“The progress of the different races was unequal,” noted Roy Chapman Andrews, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in the 1920s and 1930s. “Some developed into masters of the world at an incredible speed. But the Tasmanians … and the existing Australian aborigines lagged far behind, not much advanced beyond the stages of Neanderthal man.”8 Such overtly racist comments were echoed frequently in literature of the time and were reflected in the evolutionary trees published then (Fig. 1.5).

In other words, inequality of races – with blacks at the bottom and whites at the top – was explained away as the natural order of things: before 1859 as the product of God’s creation, and after 1859 as the product of evolution.

In the same vein, early discussions of human evolution incorporated the notion of progress, and specifically the inevitability of Homo sapiens as the ultimate aim of evolutionary trends. In the words of the prominent British anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith, written in 1927, “Progress – or what is the same thing, Evolution – is [Nature’s] religion,” 9,10 or, as Robert Broom put it in 1933, “Much of evolution looks as if it had been planned to result in man, and in other animals and plants to make the world a suitable place for him to dwell in.”11 (Broom was responsible for some of the more important early human fossil finds in south Africa during the 1930s and 1940s.)

FIGURE 1.4 The anthropomorpha of Linnaeus: In the mid-eighteenth century, when Linnaeus compiled his Systema Naturae, Western scientific knowledge about the apes of Asia and Africa was sketchy at best. Based on the tales of sea captains and other transient visitors, fanciful images of these creatures were created. Here, produced from a dissertation of Linnaeus’ student Hoppius, are four supposed “manlike apes,” some of which became species of Homo in Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae. From left to right: Troglodyta bontii, or Homo troglodytes, in Linnaeus; Lucifer aldrovandii, or Homo caudatus; Satyrus tulpii, a chimpanzee; and Pygmaeus edwardi, an orangutan.

In this brief historical sketch we can see the main themes of human evolution and its controversies, and what is perhaps striking is the extent to which the issues that form the primary subject matter of this book were present not only among the founding fathers of evolutionary biology, but even prior to that. In both the Great Chain of Being and evolutionary trees we have the strong idea that nature can be seen as a continuity of form, on which humans can be placed. Among both natural philosophers and evolutionary biologists there is the problem of how to find a place within these schemes for humans that can reflect both their unique abilities and their evolutionary heritage. And finally, there is the idea of change, or progress to some, whereby something that was not present at one stage of evolution, or history, does emerge, and comes to thrive.

Humans, race, and progress

FIGURE 1.5 Racism in anthropology: In the early decades of the twentieth century, racism was an implicit part of anthropology, with “white” races considered to be superior to “black” races, through greater effort and struggle in the evolutionary race. Here, the supposed ascendancy of the “white” races is shown explicitly, in Earnest Hooton’s Up from the Ape, second edition, 1946.

Modern paleoanthropology, the study of human evolution, has amassed a huge amount of evidence to help solve these problems (Fig. 1.6), and has available to it methods entirely undreamt of by the Victorians, but nonetheless it is worth remembering that it was within four years of the publication of The Origin of Species that Thomas Huxley had put his finger on the central problem of human evolution – namely our place in nature, or how we can both “mind the gap” and still remain faithful to evolutionary biology. As we shall see, archeology, fossils, and genetics have all provided ways of filling the gap between humans and the apes, which Huxley had thought unbridgeable. The science of paleoanthropology has emerged to fill the gap. In particular, it can set out to answer two major questions: first, whether the differences between humans and other animals are ones of degree or ones of kind, and second, the extent to which humans are not only unique in the sense that they are different as any species might be, but also uniquely different in the way they have acquired their basic characteristics.12

That these questions remain to be answered can be illustrated with reference to two biologists’ thoughts on the subject of the gap. At one extreme is Julian Huxley, grandson of Thomas Henry, who suggested that humankind’s special intellectual and social qualities were such that they should be recognized formally by assigning Homo sapiens to a new grade, the Psychozoan. “The new grade is of very large extent, at least equal in magnitude to all the rest of the animal Kingdom, though I prefer to regard it as covering an entirely new sector of the evolutionary process, the psychosocial, as against the entire non-human biological sector.”13 At the other end lies Jared Diamond, who argued on the basis of genetic evidence that humans should actually be placed in the same category as chimpanzees, and that we are in fact nothing more than the “third chimpanzee.”14 The power of the study of human evolution is that the answers to these questions can now be treated empirically as well as philosophically.

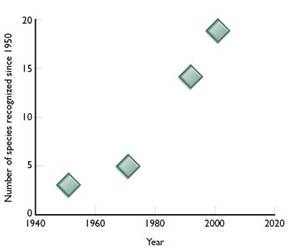

FIGURE 1.6 The growth of the hominin fossil record: While changes in approach and perception have been important in the development of our understanding of human evolution, one of the most important factors has been the growth of the fossil record. When Darwin wrote The Origin of Species there were virtually no fossils known; now they number in their thousands. This graph shows changes in the number of hominin species recognized. (Courtesy of Robert Foley.)

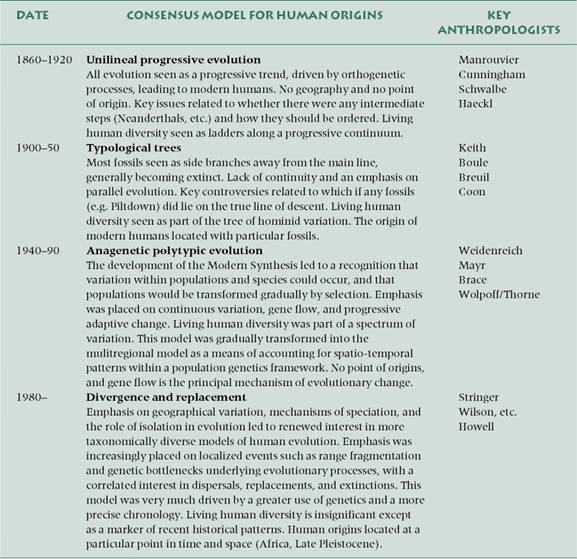

Debate over human origins has advanced substantially in recent years, particularly in broadening the scientific basis of the discussions. Nevertheless, many of the issues addressed in current research have deep historical roots. A brief sketch of the subject’s progress during the past 100 years or so will put modern debates into historical context.

KEY QUESTION How has the way scientists have perceived the relationship between humans and other animals changed over a century and a half of research and discovery?

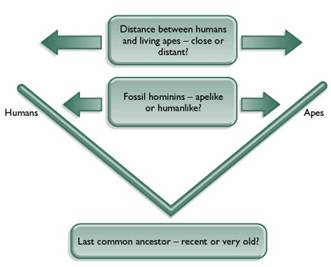

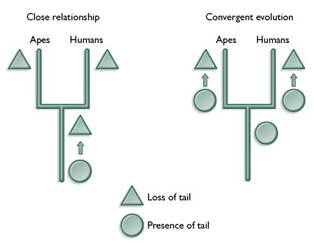

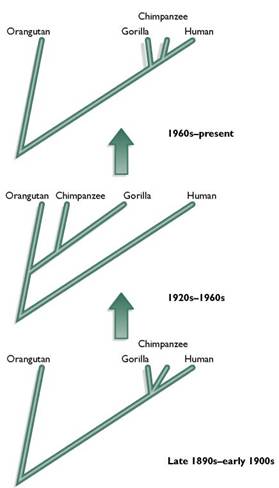

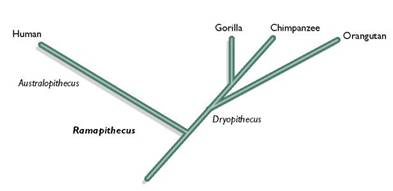

Two principal themes have been recurrent in the last century of paleoanthropology (Fig. 1.7). First is the relationship between humans and apes: how close, how distant? Second is the “humanness” of our direct ancestors, the early hominins – do the characteristics of humanity go back to the very earliest hominins and beyond, or are they a recent acquisition? (“Hominin” is the term now generally used to describe species in the human family, or clade; until recently, the term “hominid” was used, as discussed in chapter 8.)

FIGURE 1.7 Two themes in human evolutionary research: Two questions have dominated research in human evolution, the first being how close or distant humans and apes are, and the second the extent to which fossil hominins are more humanlike or more apelike.

Ideas about both these themes have fluctuated considerably during the last century.15–18 The issue of our related-ness to the apes has gone full circle. From the time of Darwin, Huxley, and Ernst Haeckel, the famous nineteenth-century German evolutionist, until soon after the turn of the last century, humans’ closest relatives were regarded as being the African apes, the chimpanzee and gorilla, with the Asian great ape, the orangutan, being considered to be somewhat separate. From the 1920s until the 1960s, humans were distanced from the great apes, which were said to be an evolutionarily closely knit group. Since the 1960s, however, conventional wisdom has returned to its Darwinian cast.

This shift of opinions has, incidentally, been paralleled by a related shift in ideas on the location of the “cradle of mankind.” Darwin plumped for Africa, Asia became popular in the early decades of the twentieth century, and Africa has once again emerged as the focus.

While this human/African-ape wheel has gone through one complete revolution, the question of the humanness of the hominin lineage has been changing as well – albeit in a single direction. Specifically, hominins, with the exception of Homo sapiens itself, have been gradually perceived as less humanlike in the eyes of paleoanthropologists, particularly since the 1980s. The different views on the origin of modern humans are taken from different perspectives on this issue. However, the two themes are in practice deeply intertwined. Determining which ape or monkey humans are most closely related to is dependent upon what traits are considered to be important to “being human,” and so the extent to which they can be traced back to a common ancestor.

In his Descent of Man,19 Darwin identified those characteristics that apparently make humans special – intelligence, manual dexterity, technology, and uprightness – and argued that an ape endowed with minor amounts of each of these qualities would surely possess an advantage over other apes. Once the earliest human forebear became established upon this evolutionary trajectory, the eventual emergence of Homo sapiens appeared almost inevitable because of the continued power of natural selection. In other words, hominin origins became explicable in terms of human qualities, and hominin origin therefore equated with human origin. It was a seductive formula, and one that persisted until quite recently.

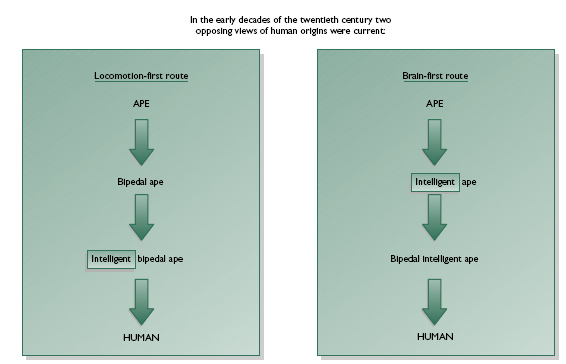

FIGURE 1.8 Two models of the pattern of human evolution: Human evolution has, in terms of anatomy, been characterized as involving two major changes – the evolution of upright walking, and the evolution of larger brains. One general set of models has viewed brains as leading the way, while another reverses the sequence. Some models have also suggested that there is simultaneous evolution. Earlier work tended to support brain-led models, whereas more recent work has tended toward bipedalism coming earlier, and no strong linkage between the two.

Was human evolution driven by intelligence?

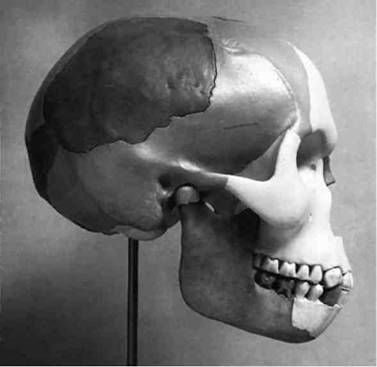

Darwin’s human traits set the agenda for the intellectual debate that occurred at the beginning of the last century concerning the order in which the major anatomical changes occurred in the human lineage (Fig. 1.8). One notion was that the first step on the road to humanity was the adoption of upright locomotion. A second idea held that the brain led the way, producing an intelligent but still arboreal creature. It was into this intellectual climate that the perpetrator of the famous Piltdown hoax – a chimera of fragments from a modern human cranium and an orangutan’s jaw, both doctored to make them look like ancient fossils – made his play in 1912 (Fig. 1.9).20 (In mid-1996 the first material clues as to the identity of the Piltdown forger came to light, pointing to Martin Hinton, the British anthropologist and Arthur Smith Woodward’s colleague at the Natural History Museum, London.)

The Piltdown “fossils” appeared to confirm not only that the brain did indeed lead the way (in other words, it was the first important human trait to evolve, and others, such as bipedalism or upright walking, were consequences of having a larger brain), but also that something close to the modern sapiens form was extremely ancient in human history. The apparent confirmation of this latter fact – extreme human antiquity – was important to both Sir Arthur Keith and Henry Fairfield Osborn (director of the American Museum of Natural History in the early decades of the twentieth century), because their theories demanded it. One consequence of Piltdown was that Neanderthal – one of the few genuine fossils of the time – was disqualified from direct ancestry to Homo sapiens, because it apparently came later in time than Piltdown and yet was more primitive.

FIGURE 1.9 Piltdown man: a fossil hybrid and fake: A cast of the Piltdown reconstruction, based on lower jaw, canine tooth, and skull fragments (shaded dark). The ready acceptance of the Piltdown forgery – a chimera of a modern human cranium and the jaw of an orangutan – derived from an adherence to the brain-first route. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.)

For Osborn, Piltdown represented strong support for his Dawn Man theory, which stated that humankind originated on the high plateaus of Central Asia, not in the jungles of Africa. During the 1920s and 1930s, Osborn was locked in constant but gentlemanly debate with his colleague, William King Gregory, who carried the increasingly unpopular Darwin-and-Huxley torch for a close relationship between humans and African apes – the Ape Man theory.

Although Osborn was never very clear about what the earliest human progenitors might have looked like, his ally Frederic Wood Jones espoused firmer ideas. Wood Jones, a British anatomist, interpreted key features of ape and monkey anatomy as specializations that were completely absent in human anatomy. In 1919, he proposed his “tarsioid hypothesis,” which sought human antecedents very low down in the primate tree, with a creature like the modern tarsier. In today’s terms, this proposal would place human origins in the region of 50 million to 60 million years ago, close to the origin of the primate radiation (see chapter 6), while Keith’s notion of some kind of early ape would date this development to approximately 30 million years ago (Fig. 1.10).

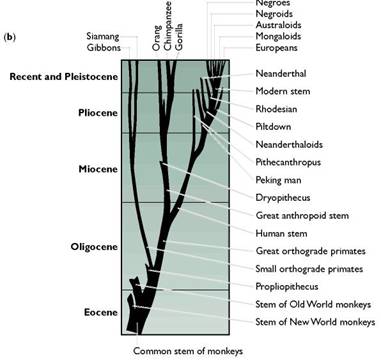

During the 1930s and 1940s, the anti-ape arguments of Osborn and Wood Jones were lost, but Gregory’s position did not immediately prevail. Gregory had argued for a close link between humans and the African apes on the basis of shared anatomical features. Others, including Adolph Schultz and D. J. Morton (two scientists who laid the foundations of primate evolution and anatomy in the first part of the twentieth century), claimed that, although humans probably derived from apelike stock, the similarities between humans and modern African apes were the result of parallel evolution (Fig. 1.11). This position remained dominant through the 1960s, firmly supported by Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, Britain’s most prominent primate anatomist of the time. Humans, it was argued, came from the base of the ape stock, not later in evolution with the specializations developed by the African apes.21

During the 1950s and 1960s, the growing body of fossil evidence related to early apes appeared to show that these creatures were not simply early versions of modern apes, as had been tacitly assumed. This idea meant that those authorities who accepted an evolutionary link between humans and apes, but rejected a close human/ African ape link, did not have to retreat back in the history of the group to “avoid” the specialization of the modern species. At the same time, those who insisted that the similarities between African apes and humans reflected a common heritage, not parallel evolution, were forced to argue for a very recent origin of the human line. Prominent among proponents of this latter argument was Sherwood Washburn, of the University of California, Berkeley (Fig. 1.12).22

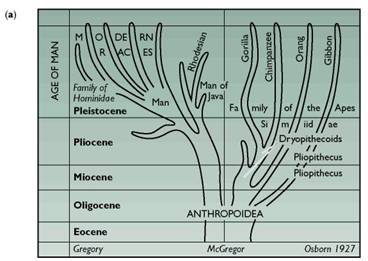

FIGURE 1.10 Two phylogenetic trees: (a) Henry Fairfield Osborn’s 1927 view of human evolution shows a very early division between humans and apes (in today’s geological scale, this division would be about 30 million years ago). (b) Sir Arthur Keith’s slightly earlier rendition also shows a very early human/ape division. Long lines link modern species with supposed ancestral stock, a habit that was to persist until quite recently. Note also the very long history of modern human races.

FIGURE 1.11 Shared descent and parallel evolution: The shared characteristics of apes and humans were thought by some, such as Gregory and Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, to be the result of the two lineages having a close relationship and thus many traits having evolved in a common ancestor. Others, including Adolph Schultz and D. J. Morton, viewed these traits as having evolved in parallel independently in different lineages, and did not see the traits as evidence of a close relationship.

Do humans and African apes have a special relationship?

One of the fossil discoveries of the 1960s – in fact, a rediscovery – that appeared to confirm the notion of parallel evolution to explain human/African ape similarities was made by Elwyn Simons, then of Yale University. The fossil specimen was Ramapithecus, an apelike creature that lived in Eurasia approximately 15 million years ago and appeared to share many anatomical features (of the teeth and jaws) with hominins (Fig. 1.13). Simons, later supported closely by David Pilbeam (now of Harvard University), proposed Ramapithecus as the beginning of the hominin line, thus excluding a human/African ape connection.23

Arguments about the relatedness of humans and African apes were mirrored by a reconsideration of relatedness among the apes themselves. In 1927, G. E. Pilgrim, a geologist who discovered the important Ramapithecus fossils in the 1920s, had suggested that the great apes be treated as a natural group (that is, evolutionarily closely related), with humans viewed as more distant. This idea eventually became popular and remained the accepted wisdom until molecular biological evidence undermined it in 1963, via the work of Morris Goodman at Wayne State University. Goodman’s molecular biology data on blood proteins indicated that humans and the African apes formed a natural group, with the orangutan more distant.24

As a result, the Darwin/Huxley/Haeckel position returned to prominence, with first Gregory and then Washburn emerging as its champion. Subsequent molecular biological – and fossil – evidence appeared to confirm Washburn’s original suggestion that the origin of the human line is quite recent, close to 5 million years ago. Ramapithecus was no longer regarded as the first hominin, but simply one of many early apes. (The nomenclature and evolutionary assignment of Ramapithecus subsequently were modified, too.)

Meanwhile, discoveries of fossil hominins, and the stone tools they apparently made, had been accumulating at a rapid pace from the 1940s through 1970s, first in south Africa and then in east Africa. Culture – specifically, stone-tool making and tool use in butchering animals – became a dominant theme, so much so that “hominin” was considered to imply a hunter-gatherer life-style. The most extreme expression of culture’s importance as the hominin characteristic consisted of the single-species hypothesis, promulgated during the 1960s principally by C. Loring Brace and Milford Wolpoff, both of the University of Michigan.

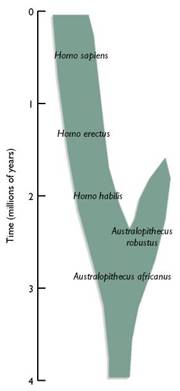

According to this hypothesis, only one species of hominin existed at any one time; human history was viewed as progressing by steady improvement up a single evolutionary ladder (Fig. 1.14). The rationale relied upon a supposed rule of ecology: the principle of competitive exclusion, which states that two species with very similar adaptations cannot coexist. In this case, culture was viewed as such a novel and powerful behavioral adaptation that two cultural species simply could not thrive side by side. Thus, because all hominins are cultural by definition, only one hominin species could exist at any one time. This was a powerful idea developed in the middle of the last century by Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr, two of the great evolutionary biologists of the twentieth century, who developed modern evolutionary theory as it is used today, and the idea came to be very influential in human evolutionary studies.25

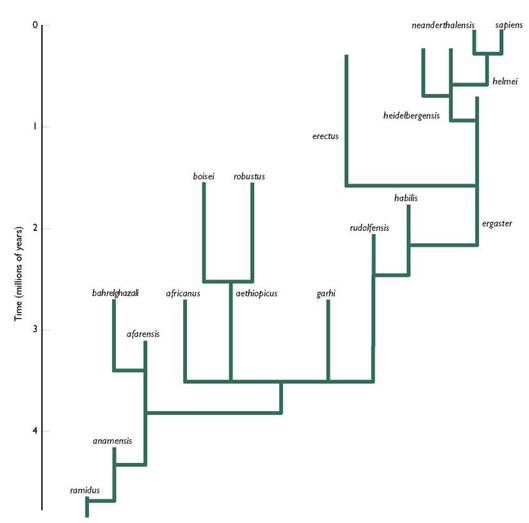

The single-species hypothesis collapsed in the mid-1970s, after fossil discoveries from Kenya undisputedly demonstrated the coexistence of two very different species of hominin: Homo erectus (or Homo ergaster), a large-brained species that apparently was ancestral to Homo sapiens, and Australopithecus boisei, a small-brained species that eventually became extinct. Subsequent discoveries and analyses implied that several species of hominin coexisted in Africa some 2 million or so years ago, suggesting that several different ecological niches were being successfully exploited. These findings implied that to be hominin did not necessarily mean being cultural. Thus, no longer could hominin origins be equated with human origins (Fig. 1.15).

FIGURE 1.12 Shifting patterns: Between the beginning of the twentieth century and today, ideas about the relationships among apes and humans have moved full circle.

FIGURE 1.13 Ramapithecus: Now considered to be related to the orangutan, Ramapithecus was at one time considered to be the first hominin and evidence for an early origin and long time scale for human evolution.

FIGURE 1.14 A single evolving lineage: After 1950 the idea of each fossil showing a separate lineage was abandoned in favor of a single sequence of evolution, with each fossil or type of fossil representing a stage of development. This became the basis for Brace and Wolpoff’s single-species hypothesis, first proposed by Teodosius Dobzhansky, that unlike other lineages, humans and their ancestors did not speciate, and so all specimens belonged to a single evolving lineage.

From the 1980s onward, not only has an appreciation of a spectrum of hominin adaptations – including the simple notion of a bipedal ape – emerged, but the lineage that eventually led to Homo sapiens has also come to be perceived as much less human. Gone is the notion of a scaled-down version of a modern hunter-gatherer way of life. In its place has appeared a rather unusual African ape adopting some novel, un-apelike modes of subsistence.

The two themes identified as being central to debates about human evolution – the specific relationship to the apes, and the antiquity of human characteristics – remain central to current research. The close relationship between humans and African apes seems to have been firmly established, and older ideas can clearly be rejected. The main inference that has now been drawn is that the basal, primate stock from which humans are derived were part of an already well-developed African ape form. However, it is also the case that these earliest hominins were still far from being human, and that the actual traits that so categorically split humanity from the rest of the primate world are not present in the early part of the evolutionary story. The result is that there are now two problems in human evolution where before there had been one – the origin of the hominin lineage, and the origin of humanness. These questions are in turn strongly interlinked to ideas about both the time-depth of human evolution and the diversity of species involved during its course (Fig. 1.16). Questions about the beginning of the hominin lineage are now firmly within the territory of behavioral ecology and do not draw upon those qualities that we might perceive as separating us from the rest of animate nature. Questions of hominin origins must now be posed within the context of primate biology.

“One of the species specific characteristics of Homo sapiens is a love of stories,” noted Glynn Isaac, “so that narrative reports of human evolution are demanded by society and even tend toward a common form.” Isaac was referring to the work of Boston University anthropologist Misia Landau,26 who has analyzed the narrative component of professional – not just popular – accounts of human origins.

KEY QUESTION How have paleoanthropologists attempted to explain human evolution?

FIGURE 1.15 The return of multiple species (an extreme radiation view): With the spectacular growth of the fossil record during the second half of the twentieth century, more than one lineage of hominin was increasingly recognized, particularly the divergence of Homo and some australopithecines (types of early hominin).

“Scientists are generally aware of the influence of theory on observation,” concludes Landau. “Seldom do they recognize, however, that many scientific theories are essentially narratives.” This is true not just of paleoanthropology, but even of the hardest sciences. One way, for example, is to look at how DNA, the most basic biological molecule, acts to make a protein, the building blocks of life. In one sense it is a chemical journey, from genetic code to complex bodily forms. The sequence from DNA to amino acid to protein and the composite individual can be told as a journey, with a starting point (conception) and an end point (adult development). There is therefore nothing “unscientific” about the fact that narrative is common to both fact and fiction; rather, it expresses that in science we are looking for causal links and these occur in temporally related events – in other words, in a narrative. However, Landau identifies several elements in paleoanthropology that make it particularly susceptible to being cast in narrative form, both by those who tell the stories and by those who listen to them. These elements arise primarily from the fact that as human evolution, like any evolutionary history, is a sequence of events occurring over time, it falls naturally into narrative form.

FIGURE 1.16 Four phases in the history of studies of human origins: These overlap considerably in time, and to some extent represent an ongoing conflict between unilineal/progressive/polytypic models stressing gradual transformation, and adaptive radiation models emphasizing divergence, isolation, and extinction of populations and species. The current conflict between multiregional and single-origin models reflects the latest manifestation of the debate, and the positions adopted are influenced by both the evidence and interpretations of evolutionary process. (Courtesy of Marta Lahr and Robert Foley.)

What drives changes in perspective on human evolution?

Placing events in the correct order is an essential part of any historical science, and should not be underrated, even if it can sometimes be unglamorous. However, if human evolution were simply a case of ordering the events, then it would indeed be the case that human evolution is akin to story telling (although in history it is as well to remember that some stories are true and others are not). There is, though, an essential second element, which is the attempt to explain causally the links between the events, to try to understand why they occurred in one particular order rather than another. This is an essential part of science – seeking causal explanations for key events.

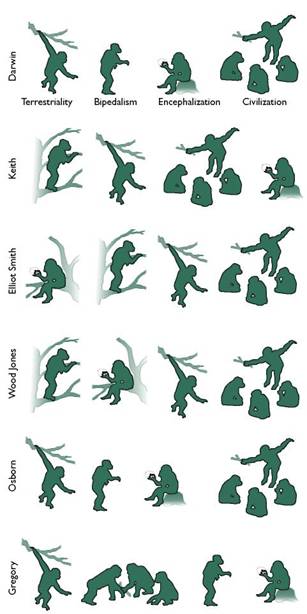

Traditionally, paleoanthropologists have recognized four key events in human evolution: the origin of terrestriality (coming to the ground from the trees), bipedality (upright walking), encephalization (brain expansion in relation to body size), and culture (or civilization) (Fig. 1.17). While these four events have usually featured in accounts of human origins, paleoanthropologists have disagreed about the order in which they were thought to have occurred and their importance in “causing” human evolution.15,16

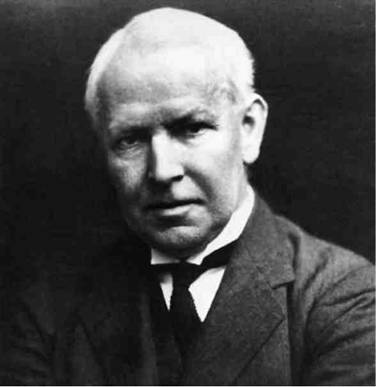

For instance, Henry Fairfield Osborn considered the order to be that given above, which, incidentally, coincides closely with Darwin’s view. Sir Arthur Keith, building on earlier ideas of D. J. Morton, considered bipedalism to have been the first event, with terrestriality following. In other words, Keith’s ancestral ape began walking on two legs while it was still a tree dweller; only subsequently did it descend to the ground. For Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, a contemporary of Keith, encephalization led the way (Fig. 1.18). His student, Frederic Wood Jones, agreed with Smith that encephalization and bipedalism developed while our ancestor lived in trees, but thought that bipedalism preceded rather than followed brain expansion. William King Gregory, like his colleague Osborn, argued for terrestriality first, but suggested that the adoption of culture (tool use) preceded significant brain expansion. And so on.

FIGURE 1.17 Different reconstructions of the sequence of events in human evolution: Even though anthropologists saw the human journey as involving the same fundamental events – terrestriality, bipedalism, encephalization, and civilization – different authorities sometimes placed these steps in slightly different orders. For instance, although Charles Darwin envisaged an ancient ape first coming to the ground and then developing bipedalism, Sir Arthur Keith believed that the ape became bipedal before leaving the trees. (Courtesy of Misia Landau/American Scientist.)

FIGURE 1.18 Sir Grafton Elliot Smith: A leading anatomist and anthropologist in early twentieth-century England, Elliot Smith often wrote in florid prose about human evolution. (Courtesy of University College, London.)

Thus, we see these four common elements linked together in different ways, with each narrative scheme purporting to tell the story of human origins. And “story” is the operative word here. “If you analyze the way in which Osborn, Keith and others explained the relation of these four events, you see clearly a narrative structure,” says Landau, “but they are more than just stories. They conform to the structure of the hero folk tale.” In her analysis of paleoanthropological literature, Landau drew upon a system devised in 1925 by the Russian literary scholar Vladimir Propp. This system, published in Propp’s Morphology of the Folk Tale, included a series of 31 stages that encompassed the basic elements of the hero myth. Landau reduced the number of stages to nine, but kept the same overall structure: hero enters; hero is challenged; hero triumphs.

In the case of human origins, the hero is the ape in the forest, who is “destined” to become us. The climate changes, the forests shrink, and the hero is cast out on the savannah where he faces new and terrible dangers. He struggles to overcome them, by developing intelligence, learning to use tools, and so on, and eventually emerges triumphant, recognizably you and me.

“When you read the literature you immediately notice not only the structure of the hero myth, but also the language,” explains Landau. For instance, Elliot Smith writes about “the wonderful story of Man’s journeyings towards his ultimate goal” and “Man’s ceaseless struggle to achieve his destiny.” Roy Chapman Andrews, Osborn’s colleague at the American Museum, writes of the pioneer spirit of our hero: “Hurry has always been the tempo of human evolution. Hurry to get out of the primordial ape stage, to change body, brains, hands and feet faster than it had ever been done in the history of creation. Hurry on to the time when man could conquer the land and the sea and the air; when he could stand as Lord of all the Earth.”

Osborn wrote in similar tone: “Why, then, has evolutionary fate treated ape and man so differently? The one has been left in the obscurity of its native jungle, while the other has been given a glorious exodus leading to the domination of earth, sea, and sky.” Indeed, many of Osborn’s writings explicitly embodied the notion of drama: “The great drama of the prehistory of man,” he wrote, and “the prologue and opening acts of the human drama,” and so on.26

Of course, it is possible to tell stories with similar gusto about non-human animals, such as the “triumph of the reptiles in conquering the land” or “the triumph of birds in conquering the air.” Such stirring tales are readily found in accounts of evolutionary history – look no further than every child’s hero, the dinosaur. The fact that the hero of the paleoanthropology tale is Homo sapiens – ourselves – makes a significant difference, however. Although dinosaurs may be lauded as lords of the land in their time, only humans have been regarded as the inevitable product of evolution – indeed, the ultimate purpose of evolution, as we saw in the previous chapter. Not everyone was as explicit about this as Broom was, but most authorities betrayed the sentiment in the hero-worship of their prose.

These stories were not just accounts of the ultimate triumph of our hero; they carried a moral tale, too – namely, triumph demands effort. “The struggle for existence was severe and evoked all the inventive and resourceful faculties and encouraged [Dawn Man] to the fashioning and first use of wooden and then stone weapons for the chase,” wrote Osborn. “It compelled Dawn Man … to develop strength of limb to make long journeys on foot, strength of lungs for running, and quick vision and stealth for the chase.”

According to Elliot Smith, our ancestors “were impelled to issue forth from their forests, and seek new sources of food and new surroundings on hill and plain, where they could obtain the sustenance they needed.” The penalty for indolence and lack of effort was plain for all to see, because the apes had fallen into this trap: “While man was evolved amidst the strife with adverse conditions, the ancestors of the Gorilla and Chimpanzee gave up the struggle for mental supremacy because they were satisfied with their circumstances.”

How is it possible to reconstruct an evolutionary narrative?

In the literature of Elliot Smith’s time,27 the apes were usually viewed as evolutionary failures, left behind in the evolutionary race. This sentiment prevailed for several decades, but eventually became transformed. Instead of evolutionary failures, the apes came to be viewed as evolutionarily primitive, or relatively unchanged from the common ancestor they shared with humans. In contrast, humans were regarded as much more advanced. Today, anthropologists recognize that both humans and apes display advanced evolutionary features, and differ equally (but in separate ways) from their common ancestor.

Although modern accounts of human origins usually avoid purple prose and implicit moralizing, one aspect of the narrative structure lingers in current literature. Some paleoanthropologists still tend to describe the events in the “transformation of ape into human” as if each event were a preparation for the next. “Our ancestors became bipedal in order to make and use tools and weapons … tool-use enabled brain expansion and the evolution of language … thus endowed, sophisticated societal interactions were finally made possible.” Crudely put, to be sure, but this kind of reasoning was common in Osborn’s day and persists in some current narratives.

Why does it happen? “Telling a story does not consist simply in adding episodes to one another,” explains Landau. “It consists in creating relations between events.” Consider, for instance, our ancestor’s supposed “coming to the ground” – the first and crucial advance on the long road toward becoming human. It is easy to imagine how such an event might be perceived as a courageous first step on the long journey to civilization: the defenseless ape faces the unknown predatory hazards of the savannah. “There is nothing inherently transitional about the descent to the ground, however momentous the occasion,” says Landau. “It only acquires such value in relation to our overall conception of the course of human evolution.”