CONTENTS

CONTRIBUTOR LIST

Editors

Contributors

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Chapter 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING

What is evidence-based nursing, and why is it important?

Getting started with evidence-based nursing

Context

Early evidence of the impact of evidence-based practice on policy, education and research

Why we wrote this book

References

Chapter 2 IMPLEMENTING EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING: SOME MISCONCEPTIONS

Evidence-based practice isn’t new; it’s what we have been doing for years

Evidence-based nursing leads to ‘cookbook’ nursing and a disregard for individualized patient care

There is an over-emphasis on randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews in evidence-based health care, and they are not relevant to nursing

Summary

References

Chapter 3 ASKING ANSWERABLE QUESTIONS

What is EBN?

Why focus questions?

Where do questions come from?

Elements of a question

Putting it all together

Different types of questions

Finding answers

References

Chapter 4 OF STUDIES, SUMMARIES, SYNOPSES, AND SYSTEMS: THE ‘4S’ EVOLUTION OF SERVICES FOR FINDING CURRENT BEST EVIDENCE

Systems

Synopses

Syntheses

Studies

Is it time to change how you seek best evidence?

References

Chapter 5 SEARCHING FOR THE BEST EVIDENCE. PART 1: WHERE TO LOOK

Textbook-like resources: systems

Synopses: distilled information sources

Consolidated information sources

The Internet

Keeping up to date

Searching for statistical data

Summary

References

Chapter 6 SEARCHING FOR THE BEST EVIDENCE. PART 2: SEARCHING CINAHL AND MEDLINE

What is CINAHL, why should I use it, and how do I access it?

What is MEDLINE, why should I use it, and how do I access it?

Searching for clinically useful articles made easy

How to apply clinical queries in CINAHL

How to apply clinical queries in MEDLINE

Additional search tips and information – CINAHL

Summary

References

Chapter 7 IDENTIFYING THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN TO FIT THE QUESTION. PART 1: QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

Questions about the effectiveness of prevention and interventions

Questions about the cause of a health problem or disease

Questions about the course of a condition or disease (prognosis)

Single studies versus systematic reviews

Summary

References

Chapter 8 IDENTIFYING THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN TO FIT THE QUESTION. PART 2: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Sampling, data collection and data analysis

Qualitative data

Types of qualitative research

Summary

References

Additional resources

Chapter 9 IF YOU COULD JUST PROVIDE ME WITH A SAMPLE: EXAMINING SAMPLING IN QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE RESEARCH PAPERS

What is sampling?

Sampling in quantitative research

Sampling in qualitative research

Quantitative and qualitative and sampling: a final word of caution

Summary

References

Additional resource

Chapter 10 THE FUNDAMENTALS OF QUANTITATIVE MEASUREMENT

Types of variables

Issues in measurement

What measurement issues should I consider when reading an article?

Summary

References

Chapter 11 SUMMARIZING AND PRESENTING THE EFFECTS OF TREATMENTS

Measures of health and disease

Measures of effect and association

Clinical importance and impact

Summary

References

Chapter 12 ESTIMATING TREATMENT EFFECTS: REAL OR THE RESULT OF CHANCE?

Sampling error

Confidence intervals

Hypothesis testing and p-values

Type I error: the risk of a false-positive result

Type II error: risk of a false-negative result

Tests for different types of outcome measures

Statistical significance is not clinical significance

Summary

References

Chapter 13 DATA ANALYSIS IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative data

Qualitative analytic reasoning processes

Specific analytic strategies

Cognitive processes inherent in qualitative analysis

Quality measures in qualitative analysis

Summary

References

Additional resources

Chapter 14 USERS’ GUIDES TO THE NURSING LITERATURE: AN INTRODUCTION

Introduction to critical appraisal

Summary

References

Chapter 15 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF TREATMENT OR PREVENTION INTERVENTIONS

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

The search

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Chapter 16 ASSESSING ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT AND BLINDING IN RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS: WHY BOTHER?

Allocation concealment

Blinding

Reporting of methods

Summary

References

Chapter 17 NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: A CLINICALLY USEFUL MEASURE OF THE EFFECTS OF NURSING INTERVENTIONS

How can NNTs help me in clinical decision-making?

NNTs are only useful for interventions that produce dichotomous outcomes

NNTs should always be interpreted in the context of their precision

Interpretation of NNTs must always consider the follow-up time associated with them

Clinical decision-making must consider adverse outcomes as well as positive effects

NNTs will vary with baseline risk

Summary

References

Chapter 18 THE TERM ‘DOUBLE-BLIND’ LEAVES READERS IN THE DARK

Summary

References

Chapter 19 EVALUATION OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS OF TREATMENT OR PREVENTION INTERVENTIONS

What is a systematic review?

The search

Are the results of the systematic review valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Additional resources

Chapter 20 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF SCREENING TOOLS AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The search

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the test in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Chapter 21 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF HEALTH ECONOMICS

Are the results of this economic evaluation valid?

What are the results of the economic evaluation?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Chapter 22 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF PROGNOSIS

Definition of prognosis

Study designs for questions of prognosis

The search

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of clinical scenario

Summary

References

Additional resources

Chapter 23 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF CAUSATION (AETIOLOGY)

The search

Types of research studies

Measures of effect in studies of causation

Are the results valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Chapter 24 EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF TREATMENT HARM

The search

Study designs for assessing questions of treatment harm

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Can I apply the results in practice?

Resolution of the scenario

References

Chapter 25 EVALUATION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH STUDIES

The search

Are the findings of the study valid?

What are the findings?

Can I apply the findings in practice?

Resolution of the clinical scenario

References

Additional resources

Chapter 26 APPRAISING AND ADAPTING CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

1. Identify a clinical area in which to promote best practice

2. Establish an interdisciplinary guideline evaluation group

3. Establish a guideline appraisal process

4. Search for and retrieve guidelines

5. Assess the guidelines

6. Adopt or adapt guidelines for local use

7. Seek external review of the proposed local guideline

8. Finalize the local guideline

9. Obtain official endorsement and adoption of the guideline by the organization

10. Schedule review and revision of the local guideline

Resolution of clinical scenario

Summary

References

Chapter 27 MODELS OF IMPLEMENTATION IN NURSING

Conceptual models and theories of implementation

Resolution of the clinical scenario

Summary

References

Chapter 28 CLOSING THE GAP BETWEEN NURSING RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Evaluation of behaviour change strategies

Getting research into practice

Planning for improving the practice of individual nurses

References

Chapter 29 PROMOTING RESEARCH UTILIZATION IN NURSING: THE ROLE OF THE INDIVIDUAL, THE ORGANIZATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Contexts of research utilization

The individual nurse

The organization

The environment: research quality and dissemination strategies

Summary

References

Chapter 30 NURSES, INFORMATION USE, AND CLINICAL DECISION-MAKING: THE REAL-WORLD POTENTIAL FOR EVIDENCE-BASED DECISIONS IN NURSING

Methods underpinning this chapter

Evidence-based decision-making involves actively using information

Information need, ‘information behaviour’ and clinical decision-making

Nurses’ clinical decisions: a typology

The cognitive continuum: the decision as driver for information behaviour

The reality of information behaviour

Decision-making and models for the implementation of research knowledge

Summary

References

Chapter 31 COMPUTERIZED DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS IN NURSING

Types of decisions suitable for the use of CDSSs

Examples of CDSSs used in nursing

Evaluations of CDSSs

Summary

References

Additional resources

Chapter 32 BUILDING A FOUNDATION FOR EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: EXPERIENCES IN A TERTIARY HOSPITAL

Selecting a model for EBN practice and an EBP model for implementing change in nursing practice

Prioritizing and disseminating research findings to health care programmes

Evaluating an important EBP application in direct patient care

Other progress

Summary

References

GLOSSARY

INDEX

© 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing

Company Ltd, and American College of Physicians (“ACP”) Journal Club

Blackwell Publishing editorial offices:

Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1865 776868

Blackwell Publishing Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

Tel: +1 781 388 8250

Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

Tel: +61 (0)3 8359 1011

The right of the Authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

First published 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-4051-4597-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Evidence-based nursing : an introduction / editors, Nicky Cullum…[et al.].

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-4597-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4051-4597-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Evidence-based nursing. I. Cullum, Nicky.

[DNLM: 1. Nursing Process. 2. Evaluation Studies. 3. Evidence-Based Medicine. WY

100 E93 2007]

RT42.E93 2007

610.73—dc22

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met acceptable environmental accreditation standards.

For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website:

www.blackwellnursing.com

CONTRIBUTOR LIST

Donna Ciliska PhD, RN

Professor

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Nicky Cullum PhD, RGN

Professor and Director of the Centre for Evidence Based Nursing

Department of Health Sciences

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

University of York

York, UK

YO10 5DD

R. Brian Haynes MD (Alberta), MSc (McMaster), PhD (McMaster), FRCPC, MACP, FACMI,

Michael Gent Professor and Chair, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics,

DeGroote School of Medicine

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Susan Marks BEd, BA

Research Associate

Health Information Research Institute (HIRU)

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Joy Adamson PhD

Lecturer

Department of Health Sciences

University of York

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

York, UK

YO10 5DD

Suzanne Bakken DNSc, FAAN

Alumni Professor

School of Nursing and Professor of Biomedical Informatics

Columbia University School of Nursing

617 West 168th Street

New York

NY 10032

USA

Jennifer Blythe PhD, MLS

Senior Scientist

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Deborah Braccia RN, MPA

Doctoral Candidate

Columbia University School of Nursing

617 West 168th Street

New York

NY 10032

USA

Esther Coker RN, MScN, MSc

Assistant Clinical Professor

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Clinical Nurse Specialist

St. Peter’s Hospital

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8M 1W9

P.J. Devereaux BSc (Dalhousie), MD (McMaster), PhD (McMaster), FRCPC

Assistant Professor

Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Alba DiCenso PhD, RN

Professor, Nursing and Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics

CHSRF/CIHR Chair in Advanced Practice Nursing

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Dawn Dowding PhD, RGN

Senior Lecturer

Hull York Medical School

Department of Health Sciences

University of York

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

York, UK

Y010 5DD

Ellen Fineout-Overholt RN, PhD, FNAP

Director, Center for the Advancement of Evidence Based Practice

Associate Professor, Clinical Nursing

Arizona State University

College of Nursing

500 N. 3rd Street

Phoenix

AZ 85004

USA

Kate Flemming MSc, RGN

Research Fellow

Department of Health Sciences

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

University of York

York, UK

YO10 5DD

Ian D. Graham PhD

Associate Professor

School of Nursing

University of Ottawa

51 Gwynne Ave

Ottawa

ON, Canada

K1Y 1X1

David M. Gregory RN, PhD

Professor

School of Health Sciences

University of Lethbridge

AH103 (Anderson Hall)

Lethbridge

AB, Canada

T1K 3M4

Margaret B. Harrison RN, PhD

Professor

School of Nursing

Queen’s University

Second Floor

78 Barrie Street

Kingston

ON, Canada

K7L 3N6

Andrew Jull RN, MA

Research Fellow

Clinical Trials Research Unit

University of Auckland

Private Bag 92019

Auckland

New Zealand 1142

Bernice King RN, MHSc

Assistant Clinical Professor (retired)

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Hamilton Health Sciences

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8V 5C2

Jo Logan RN, PhD

Adjunct Professor

School of Nursing

University of Ottawa

213 Beech St

Ottawa

ON, Canada

K1Y 3T3

Dorothy McCaughan MSc, RGN

Research Fellow

Department of Health Sciences

University of York

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

York, UK

YO10 5DD

K. Ann McKibbon MLS, PhD

Associate Professor

Health Information Research Unit

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Bernadette Melnyk RN, PhD, CPNP, FAAN

Dean and Distinguished Foundation Professor in Nursing

Arizona State University

500 North 3rd Street

Phoenix

AZ 85004

USA

E. Ann Mohide RN, MHSc, MSc

Associate Professor

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Mary Ann O’Brien BHSc (PT), MSc

Research Fellow

Supportive Cancer Care Research Unit

Juravinski Cancer Centre

699 Concession Street, Room 4–204

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8V 5C2

Emily Petherick MPH

Research Fellow

Department of Health Sciences

University of York

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

York, UK

YO10 5DD

Jenny Ploeg RN, PhD

Associate Professor

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Pauline Raynor BA, PGCE, RN, RM

Bradford Health Research Centre

Bradford Royal Infirmary

Duckworth Lane

Bradford

UK

BD9 6RJ

Jackie Roberts RN, MSc

Professor Emeritus, School of Nursing

Systems Linked Research Unit

McMaster University

75 Frid Street

Building T30

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8P 4M3

Nicole Robinson BA

Research Coordinator

Ottawa Health Research Institute

1053 Carling Avenue

Ottawa

ON, Canada

K1Y 4E9

Joan Royle RN, MScN

Associate Professor (retired)

School of Nursing

McMaster University

Hamilton

ON, Canada

L8N 3Z5

Cynthia Russell PhD, RN

Professor

University of Tennessee

Health Science Center

College of Nursing

877 Madison Avenue

Memphis

TN 38163

USA

Kenneth F. Schulz PhD, MBA

Vice President, Family Health International

PO Box 13950

Research Triangle Park North Carolina

NC 27709

USA

Trevor A. Sheldon DSc

Professor and Deputy Vice Chancellor

University of York

Heslington Hall

York, UK

YO10 5DD

Patricia W. Stone PhD, RN

Assistant Professor of Nursing

Columbia University School of Nursing

617 West 168th Street

New York

NY 10032

USA

Jacqueline Tetroe MA

Senior Policy Analyst

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

160 Elgin St, 9th Floor

Address Locator 4809A

Ottawa

ON, Canada

K1A 0W9

Carl Thompson PhD, RGN

Senior Lecturer

Department of Health Sciences

University of York

Area 2, Seebohm Rowntree Building

York, UK

YO10 5DD

Sally Thorne PhD, RN

Professor

School of Nursing

University of British Columbia

T201–2211, Wesbrook Mall

Vancouver

BC, Canada

V6T 2B5

Jennifer Wiernikowski RN, MN, CON(C)

Chief of Nursing Practice

Juravinski Cancer Program

Hamilton Health Sciences

Hamilton,

ON, Canada

L8V 5C2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Laurie Gunderman, Sarah Marriott, Sandi Newby and Emily Petherick for their help in preparing material for this book.

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to those nurses everywhere who are striving to make more informed decisions in order to deliver the best nursing, health care management and policy development that they can.

COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Chapter 2

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Implementing evidence-based nursing: some misconceptions’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 38–39. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 3

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Asking answerable questions’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 36–37. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 4

Haynes RB. ‘Of studies, synopses, and systems: the “4S” evolution of the services for finding current best evidence’. Originally published in American College of Physicians Journal Club 2001 134: A11–A13 and has been adapted and reproduced with permission.

Chapter 5

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Searching for best evidence. Part 1: Where to look’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 68–70. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 6

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Searching for best evidence. Part 2: Searching CINAHL and MEDLINE’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 105–107. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 7

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Identifying the best research design to fit the question. Part 1: Quantitative research’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1999 2: 4–6 under the title Identifying the best research design to fit the question. Part 1: quantitative designs. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 8

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Identifying the best research design to fit the question. Part 2: Qualitative designs’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1999 2: 36–37 under the original title Identifying the best research design to fit the question. Part 2: qualitative designs. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 9

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘If you could just provide me with a sample: examining sampling in qualitative and quantitative research papers’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1999 2: 68–70. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 10

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘The fundamentals of qualitative measurement’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1999 2: 100–101. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 11

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Statistics for evidence-based nursing’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2000 3: 4–6. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 12

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Estimating treatment effects: real or the result of chance?’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2000 3: 36–39. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 13

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Data analysis in qualitative research was first published’ in Evidence Based Nursing 2000 3: 68–70. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 14

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Users’ guides to the nursing literature: an introduction’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2000 3: 71–72. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 15

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of treatment or prevention interventions’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2000 3: 100–102. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 16

Schultz KF. ‘Assessing allocation and blinding in randomized controlled trials: Why bother?’ Originally published in American College of Physicians Journal Club 2000 132: A11–A12 and has been adapted and reproduced with permission.

Chapter 17

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of the effects of nursing interventions’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2001 4: 36–39 under the title Clinically useful measures of the effects of treatment. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 18

Devereaux PJ, et al. ‘Double blind, you are the weakest link – good-bye!’. Originally published in American College of Physicians Journal Club 2002 136: A11–A12, and has been adapted and reproduced with permission.

Chapter 19

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of systematic reviews of treatment or prevention interventions’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2001 4: 100–104. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 20

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of screening tools and diagnostic tests’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2002 5: 68–72 under the title Evaluation of studies of assessment and screening tools, and diagnostic tests. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 21

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of health economics’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2002 5: 100–104. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 22

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of prognosis’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2004 7: 4–8. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 23

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of causation (aetiology)’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2004 7: 36–40. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 24

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of studies of treatment harm’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2006 9: 100–104. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 25

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Evaluation of qualitative research studies’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2003 6: 36–40. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 26

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Appraising and adapting clinical practice guidelines’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2005 8: 68–72 under the title Evaluation and adaptation of clinical practice guidelines. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 28

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Closing the gap between nursing research and practice’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 7–8. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 29

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Promoting research utilisation in nursing: the role of the individual, organisation, and environment’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 1998 1: 71–72. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 30

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Nurses, information use, and clinical decision-making: the real-world potential for evidence-based decisions in nursing’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2004 7: 68–72. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

Chapter 32

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd, 2007. All Rights Reserved.

‘Building a foundation for evidence-based practice: experiences in a tertiary hospital’ was first published in Evidence Based Nursing 2003 6: 100–103. See http://ebn.bmj.com/. This reprint (as adapted) is published by arrangement with BMJ Publishing Group Limited and RCN Publishing Company Ltd.

The term ‘evidence-based’ is really very new. The first documented use of the term is credited to Gordon Guyatt and the Evidence Based Medicine Working Group in 1992.[1] They described evidence-based medicine as ‘a new paradigm for medical practice’, in which evidence from clinical research should be promoted over intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiology.[1] Shortly thereafter, the term was applied to many other aspects of health care practice and further afield. We now have evidence-based nursing, evidence-based physiotherapy,* and even evidence-based policing[2] (see Box 1.1 for more examples)! Definitions vary, and sometimes the central concept becomes diluted, but at its core evidence-based ‘anything’ is concerned with using valid and relevant information in decision-making. In health care, most people agree that high-quality research is the most important source of valid information, along with information about the specific patient or population under consideration. Evidence-based ways of thinking have emerged from the discipline of clinical epidemiology, which focuses on the application of epidemiological science to clinical problems and decisions (epidemiological science is the study of health and disease in populations). These roots in epidemiology have enabled the development of a clear-sighted framework for thinking about research and its application to decisionmaking, and it is these concepts and approaches that we discuss in this book.

Box 1.1 Examples of evidence-based everything[2]

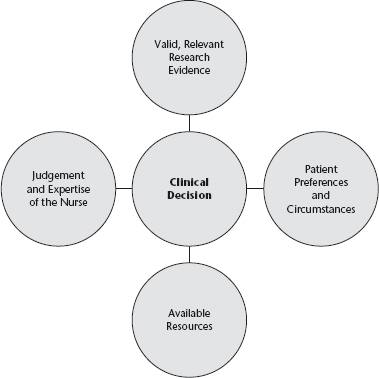

Evidence-based nursing can be defined as the application of valid, relevant, research-based information in nurse decision-making. Research-based information is not used in isolation, however, and research findings alone do not dictate our clinical behaviour. Rather, research evidence is used alongside our knowledge of our patients (their symptoms, diagnoses, and expressed preferences) and the context in which the decision is taking place (including the care setting and available resources), and in processing this information we use our expertise and judgement. The inputs to evidence-based decision-making are depicted in Figure 1.1. Research has shown, however, that many practitioners simply don’t see research evidence as being useful and accessible when making real-life clinical decisions.[3] The grand challenge is therefore showing how this can be achieved, and the quality of care enhanced.

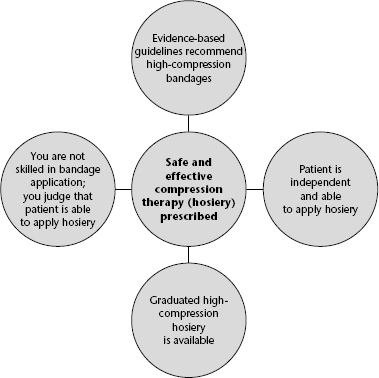

Imagine that, as a community-based nurse, you are responsible for providing care to an otherwise fit 74-year-old man with a chronic venous leg ulcer. Your locally relevant, evidence-based, leg ulcer guideline tells you that high-compression bandaging, such as the four-layer bandage, should be the first line of treatment, is eminently deliverable in a community setting, and is cost-effective.[4] You have been trained, and are competent, in the application of this bandage and, therefore, proceed to prescribe it for this patient. Contrast this decision with an alternative scenario, one in which all variables are the same, except that you are inexperienced in bandage application. You know that poor bandage application technique can have disastrous consequences for the patient – including amputation. Under these circumstances, you decide to prescribe graduated compression hosiery (stockings) rather than bandages. You know that graduated compression hosiery applies a similar level of compression to the four-layer bandage, and, after determining that the patient is able to apply the stockings himself, you concede that these will also be the safer option given your lack of skill in bandaging. If your patient had arthritic hands and was unable to apply stockings, or did not have the facilities to wash the stockings, your decision would probably have been different (see Figure 1.2). At any given time, the research evidence informing a decision is a constant; however, you must use your professional judgement to determine how you will apply it to the patient in front of you. Obviously, it is also important to remember that, as new research is published, the evidence base will change, and you will need to become aware of important changes in evidence relevant to your practice (see Chapter 5 for information on alerting services).

Figure 1.1 The components of an evidence-based nursing decision.

Figure 1.2 Resolution of a decision problem: how research evidence, judgement, patient preferences and circumstances, and knowledge about local resources interplay.

There are many ways to begin introducing research evidence into practice. At the simplest level, you might identify an area of practice for which you are responsible, find out if any evidence-based clinical practice guidelines exist, critically appraise them to determine if they are valid, and consider how they might be applied locally. Chapter 26 outlines this very process. In areas where guidelines don’t exist, you might, in collaboration with colleagues, identify recurring uncertainties in your clinical area. Next, you would translate your single uncertainty (e.g. Is it really necessary for people to lie flat for 8 hours after lumbar puncture?) into a focused, answerable question. Chapter 3 outlines how to develop focused, answerable questions. For the lumbar puncture example, the question might be as follows: In patients having cervical or lumbar puncture, is longer bed rest more effective than immediate mobilization or short bed rest in preventing headache? This question is clearly about whether a particular intervention (lying flat for a long time) is better or worse than an alternative (not lying flat or lying flat for a brief time). Chapters 7 and 8 explain how certain types of clinical question demand research evidence from particular research designs because the answers are more likely to be valid, or true. In the above example, where the question concerns an intervention or therapy, the answer is best provided by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (or, even better, by a systematic review of all relevant RCTs). You would then move into the searching phase to identify relevant RCTs or reviews; Chapters 4, 5 and 6 will guide you through the searching process. The next step is to grapple with assessing the quality of the research you find. We cannot accept the results of research at face value because, irrespective of where research has been published, and by whom, most research is not fit for immediate application. This is best illustrated by the fact that only about 5.4% of the approximately 50 000 articles published in 120 journals, and scrutinized for three evidence-based journals (Evidence-Based Nursing, Evidence-Based Medicine, and ACP Journal Club), reached the required methodological standard (personal communication, A McKibbon, 20 December 2006).

Fortunately several resources of pre-appraised research now exist, and these are discussed in Chapter 4. If your search does not identify any pre-appraised evidence, you will need to appraise the research you find so that you can judge whether the results are valid and ready for use in practice. Chapters 15–26 lead you through the process of critically appraising reports of study designs you will commonly encounter. Finally, Chapters 27–32 consider different aspects of research utilization: theoretical models (Chapter 27), empirical evidence of interventions aimed at changing professional behaviour (Chapter 28), the influence of the organization on research utilization (Chapter 29), use of research in clinical decision-making (Chapter 30), the emergence of computerized decision support systems in nursing (Chapter 31), and one hospital’s experiences of promoting evidence-based nursing (Chapter 32).

The emergence of evidence-based practice could not have happened at a more important time for nursing. The role of the nurse is not a fixed phenomenon; it varies by geography and culture and is heavily influenced by parameters such as the national economy and the supply of doctors. As we write this book at the beginning of the 21st century, never has the demand for health care been so high, and most countries are struggling to meet this demand. The flexibility inherent in the nursing role is widely used to respond to this demand for health care. For example, in 2000, the United Kingdom (UK) Department of Health’s Chief Nursing Officer announced 10 new roles for nurses, and nurses are now adopting these new roles widely (Box 1.2).[5] These new roles were previously held only (formally, at least) by doctors (e.g. prescribing drugs,† ordering diagnostic tests, etc.). It is difficult to imagine how nurses will be able to take on these challenging new roles and responsibilities without developing knowledge of clinical epidemiology and adopting an approach to decision-making that is informed by evidence.

Box 1.2 The Chief Nursing Officer’s 10 new roles for nurses[5]

At this point, it is probably worth pausing to reflect on how quickly nursing research has developed. The first nursing research journal (Nursing Research) was only launched in 1952. Early nursing research mainly used methodologies taken from the social sciences and largely focused on nurse education and nurses themselves. The second issue of Nursing Research contained nine research articles, four of which were about nursing students and nurse education. Since these early days, nursing research has developed apace, and there are now more than 1200 journals indexed in CINAHL, with 5400 research articles (identified by the search term ‘nurs$’) entering the CINAHL index in the year 2005 (searched by N. Cullum, 8 January 2007). In 1998, the Evidence-Based Nursing journal was launched, only 3 years after the launch of Evidence-Based Medicine (both published by the BMJ Publishing Group).

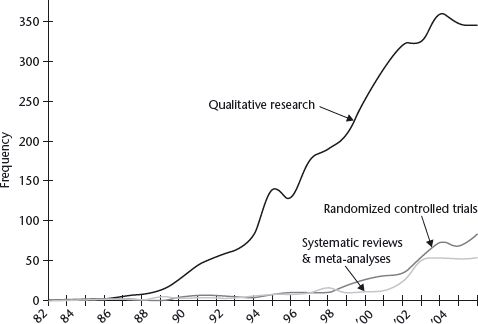

Evidence-based practice in general, and evidence-based nursing in particular, can be viewed as complex innovations, and it would be naïve to expect rapid and comprehensive uptake. Nevertheless, there is ample evidence of the impact of ‘evidence-based’ thinking on policy and education, paralleled by a rapidly growing research evidence base in clinical nursing topics. The Nursing and Midwifery Council, which governs nursing professional practice and nurse education in the UK, outlines in its Code of Conduct an expectation that nurses will ‘deliver care based on current evidence, best practice and, where applicable, validated research when it is available’.[6] The Nursing and Midwifery Council standards for nursing curricula demand that ‘the curriculum should reflect contemporary knowledge and enable development of evidence-based practice’.[7] Educational establishments all over the world have responded to demands from policy-makers and practitioners and developed educational programmes in evidence-based practice, ranging from half-day courses through to higher degrees. Paralleling these developments, the research evidence base for nursing decisions is also growing and maturing. In 1995, a systematic review of pressure ulcer prevention and treatment by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) at the University of York identified a total of 28 RCTs evaluating different pressure-relieving support surfaces in the entire international literature.[8] The review concluded that ‘…most of the equipment available for the prevention and treatment of pressure sores has not been reliably evaluated, and no “best buy” can be recommended’.[8] More recent reviews completed to underpin UK national clinical practice guidelines show that the number of trials has increased, with 44 RCTs of support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment.[9, 10] Importantly, gaps in the evidence base have resulted in the UK National Health Service commissioning research on pressure ulcer prevention.[11] Looking at the broader picture, Figure 1.3 shows how the numbers of RCTs and systematic reviews are growing (albeit slowly) as a proportion of the total nursing research indexed in CINAHL. This is important since observational research suggests that decisions about therapies (which, when, and to whom) are the most frequent type of decision made by nurses in acute care and primary care and that these types of decisions are best supported by research from RCTs.[12] We believe that, as evidence-based thinking increases in influence in nursing, the demand for RCTs and systematic reviews will continue to increase, and research funders will respond accordingly.

Figure 1.3 Frequency of different types of nursing research published by year (from CINAHL). CINAHL searched using the terms ‘phenomenolog$’, ‘grounded theory’, ‘ethnograph$’, ‘randomised controlled trial’, ‘randomized controlled trial’, ‘systematic review’, ‘meta analysis’. Searching was confined to the Nursing Journal subset and research papers (excluding papers about research).

Phenomenolog$ + grounded theory + ethnograph$ = qualitative.

The idea for this book grew out of our experience of producing the journal Evidence-Based Nursing since 1998. In common with other evidence-based journals produced by the Health Information Research Unit at McMaster University, Evidence-Based Nursing does not publish new research in full, but rather uses predefined methodological criteria to select, from the published literature, the best original studies and systematic reviews relevant to nurse decision-makers.[13] Full articles are then summarized in new, structured abstracts, which describe the question, methods, results, and evidence-based conclusions in a reproducible and accurate fashion. Each abstract is accompanied by a brief expert commentary written by a nurse, which discusses the context of the article, its methods, and clinical implications. Aside from this important dissemination role, the journal sought to develop evidence-based approaches to nursing through its Notebook and Users’ Guides series. We saw these articles as being useful to nurses in clinical practice (who could see real examples of how the evidence-based framework could be applied to nursing decisions), useful to student nurses for the same reasons, and useful to nurse educators who were suddenly expected to teach this stuff with little previous preparation.[7] We regularly receive requests to bring the Notebooks and Users’ Guides together as single resource, and so, in producing this book, we have had the same audience in mind: those of you who are somewhat, or completely, new to evidence-based practice, as well as those who are finding it difficult to get to grips with the concept. While the chapters of this book have mainly been developed from editorials already published in Evidence-Based Nursing, each has been scrutinized, edited, updated, and in some cases completely re-written. We hope that you will enjoy using the book in a variety of ways. The chapters can stand alone, and therefore you can dip into and out of the book depending on the immediate challenge at hand, or you can work through the book chapter by chapter. We urge you to consider doing this with colleagues so that you can share the learning experience and work through examples that are relevant and meaningful to your practice.

Most chapters include Learning Exercises, which are aimed at reinforcing the chapter material by allowing you to practise the techniques yourself; alternatively, nurse teachers might want to set these as exercises for students. Finally, we have included a comprehensive Glossary of terms that will stand alone as a useful guide to the basic concepts. We are indebted to all of our contributors who have given their time and expertise so freely and helped to bring this material completely up to date. We hope you enjoy reading the book as much as we have enjoyed producing it!

References

1 Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992;268:2420–5.

2 Evidence-based management. http://www.evidence-basedmanagement.com/movements/index.html (accessed 12 December 2006).

3 Thompson C, McCaughan D, Cullum N, Sheldon TA, Mulhall A, Thompson DR. Research information in nurses’ clinical decision-making: what is useful? J Adv Nurs 2001;36:376–88.

4 Royal College of Nursing. Clinical Practice Guidelines. The Nursing Management of Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2006. http://www.rcn.org.uk/resources/guidelines.php (accessed 12 December 2006).

5 Department of Health. The NHS Plan. 2000. http://www.nhsia.nhs.uk/nhsplan/ (accessed 12 December 2006).

6 Nursing and Midwifery Council. The NMC Code of Professional Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2004. http://www.nmc-uk.org/ (accessed 12 December 2006).

7 Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards of Proficiency for Pre-registration Nursing Education. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2004. http://www.nmc-uk.org/aSection.aspx?SectionID=32 (accessed 12 December 2006).

8 Effective Health Care. The Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Sores. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 1995. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/ehc21.pdf (accessed 12 December 2006).

9 Royal College of Nursing. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment and Prevention. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2001. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CGB/guidance/pdf/English (accessed 12 December 2006).

10 Royal College of Nursing. Clinical Practice Guidelines. The Use of Pressure-Relieving Devices (Beds, Mattresses and Overlays) for the Prevention of Pressure Ulcers in Primary and Secondary Care. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2003. http://www.rcn.org.uk/publications/pdf/guidelines/pressure-relieving-devices.pdf (accessed 12 December 2006).

11 Nixon J, Cranny G, Iglesias C, Nelson EA, Hawkins K, Phillips A, Torgerson D, Mason S, Cullum N. Randomised, controlled trial of alternating pressure mattresses compared with alternating pressure overlays for the prevention of pressure ulcers: PRESSURE (pressure relieving support surfaces) trial. BMJ 2006;332:1413.

12 McCaughan D. What decisions do nurses make? In: Thompson C, Dowding D, editors. Clinical Decision Making and Judgement in Nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002:95–108.

13 Purpose and procedure. Evid Based Nurs 2006;9:98–9.

* We will use the term ‘evidence-based practice’ to refer to the application of evidence-based principles in any aspect of health care practice.

† Since 1 May 2006, nurses in the UK can prescribe any licensed medication for any clinical condition in which they have expertise, after a period of 26 days’ training plus clinical mentorship.

The past 10 years have seen a strong movement towards evidence-based clinical practice. In 1997, the Canadian National Health Forum, chaired by Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, recommended that ‘a key objective of the health sector should be to move rapidly toward the development of an evidence-based health system, in which decisions are made by health care providers, administrators, policy makers, patients and the public on the basis of appropriate, balanced and high quality evidence.’[1][2][3]