CONTENTS

PREFACE

Midlatitude Ionospheric Dynamics and Disturbances: Introduction

1. OVERVIEW

2. MIDLATITUDE IONOSPHERIC STORMS

3. ELECTRIC FIELD COUPLING FROM THE HELIOSPHERE AND INNER MAGNETOSPHERE

4. THERMOSPHERIC CONTROL OF THE MIDLATITUDE IONOSPHERE

5. IONOSPHERIC GRADIENTS AND IRREGULARITIES

6. CONCLUSIONS

Section I: Characterization of Midlatitude Storms

Ionospheric Storms at Mid-Latitude: A Short Review

1. INTRODUCTION

2. EARLY HISTORY OF IONOSPHERIC STORM RESEARCH

3. PUBLICATION STATISTICS

4. DEFINING MIDDLE LATITUDES

5. POSITIVE IONOSPHERIC STORMS

The Mid-Latitude Trough—Revisited

1. INTRODUCTION

2. MID-LATITUDE TROUGH MORPHOLOGY

3. FORMATI ON PROCESSES OF THE MID-LATITUDE TROUGH

4. KEY ISSUES

5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Assimilation of Observations With Models to Better Understand Severe Ionospheric Weather at Mid-Latitudes

1. INTRODUCTION

2. WHY WAS THE WAAS PROBLEM NOT PREDICTED?

3. UNDERSTANDING THE DAYTIME STORM EFFECTS

4. A POSSIBLE ELECTRIC FIELD SCENARIO

5. IONOSPHERIC DATA ASSIMILATION

6. CONCLUSION

Low- and Middle-Latitude Ionospheric Dynamics Associated With Magnetic Storms

1. INTRODUCTION

2. OBSERVATIONS

3. E×B DRIFTS, NEUTRAL WINDS, AND COROTATION

4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A Data-Model Comparative Study of Ionospheric Positive Storm Phase in the Midlatitude F Region

1. INTRODUCTION

2. OBSERVATIONS AND MODEL COMPARISON

3. DISCUSSION

4. CONCLUSION

High-Resolution Observations of Subauroral Polarization Stream-Related Field Structures During a Geomagnetic Storm Using Passive Radar

1. INTRODUCTION

2. THE 17 JULY 2004 GEOMAGNETIC EVENT

3. DMSP OBSERVATIONS

4. PERIODIC MODULATION OF SAPS CHANNEL ELECTRIC FIELD

5. SUMMARY

Ionization Dynamics During Storms of the Recent Solar Maximum

1. INTRODUCTION

2. METHOD

3. RESULTS AND SUMMARY

4. FUTURE WORK

Mapping the Time-Varying Distribution of High-Altitude Plasma During Storms

1. INTRODUCTION

2. APPROACH

3. RESULTS

4. SUMMARY

Section II: Electric Field Coupling From the Heliosphere and Inner Magnetosphere

Interplanetary Causes of Middle Latitude Ionospheric Disturbances

1. INTRODUCTION

2. RESULTS

3. SUMMARY

Ionospheric-Magnetospheric-Heliospheric Coupling: Storm-Time Thermal Plasma Redistribution

1. PREAMBLE

2. INTRODUCTION

3. STORM ENHANCED DENSITY

4. RADAR OBSERVATIONS OF SED PLUMES

5. ELECTRIC FIELDS

6. SUBAURORAL POLARIZATION STREAM

7. TEC ENHANCEMENT AT THE BASE OF THE SED PLUME

8. MAGNETIC CONJUGACY CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SED

9. POLARIZATI ON TERMINATOR

10. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The Linkage Between the Ring Current and the Ionosphere System

1. INTRODUCTION

2. RING CURRENT DYNAMICS

3. COUPLING AND ITS EFFECTS

4. MODELING

5. DISCUSSION

Storm Phase Dependence of Penetration of Magnetospheric Electric Fields to Mid and Low Latitudes

1. INTRODUCTION

2. OBSERVATIONS

3. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Relating the Interplanetary-Induced Electric Fields With the Low-Latitude Zonal Electric Fields Under Geomagnetically Disturbed Conditions

1. INTRODUCTION

2. DATA SETS AND ANALYSIS METHODS

3. LLZEF PERTURBATIONS OF GEOMAGNETIC ORIGIN

4. CONCLUSION

Simulation of PPEF Effects in Dayside Low-Latitude Ionosphere for the October 30, 2003, Superstorm

1. INTRODUCTION

2. INTERPLANETARY AND GROUND-BASED MAGNETIC FIELD MEASUREMENTS RELATED TO THE OCTOBER 30, 2003, SUPERSTORM

3. MODELING OF IONOSPHERIC ELECTRON DENSITY DYNAMICS AND THE CRITICAL FREQUENCY OF F2 LAYER OVER JICAMARCA DURING THE OCTOBER 30, 2003, EVENT

Impact of the Neutral Wind Dynamo on the Development of the Region 2 Dynamo

1. INTRODUCTION

2. MODEL DESCRIPTION

3. COMPARISON OF MODEL RESULTS

4. SUMMARY

Section III: Thermospheric Control of the Mid-Latitude Ionosphere

Global Modeling of Storm-Time Thermospheric Dynamics and Electrodynamics

1. INTRODUCTION

2. MODELING GLOBAL THERMOSPHERE DYNAMICS

3. ELECTRODYNAMIC MODELING

4. DISCUSSION

5. CONCLUSION

Thermospheric Dynamics at Low and Mid-Latitudes During Magnetic Storm Activity

1. INTRODUCTION

2. SATELLITE MEASUREMENTS

3. EXAMPLES OF THE NEUTRAL ATMOSPHERIC RESPONSE IN INDIVIDUAL STORM CASE HISTORIES

4. DISCUSSION

Disturbed O/N2 Ratios and Their Transport to Middle and Low Latitudes

1. INTRODUCTION

2. COMPOSITION AND IONOSPHERIC STORMS

3. GLOBAL AND REGIONAL OBSERVATIONS OF LARGE-SCALE COMPOSITION CHANGES

4. CONCLUSIONS

Storm Time Energy Budgets of the Global Thermosphere

1. INTRODUCTION

2. MEASUREMENTS AND MODELS

3. ENERGETICS OF THE J77 THERMOSPHERE

4. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Sources of F-Region Height Changes During Geomagnetic Storms at Mid Latitudes

1. INTRODUCTION

2. THERMOSPHERIC CIRCULATION

3. CTIPE MODEL

4. RESULTS

5. CONCLUSIONS

Neutral Composition and Density Effects in the October-November 2003 Magnetic Storms

1. INTRODUCTION

2. OBSERVATIONS : MAGNETIC ACTIVITY, NEUTRAL DENSITY MEASUREMENTS, AND FUV IMAGING

3. STORM ONSET, TAD, AND INITIAL ΣO/N2 STATE

4. THERMOSPHERIC STORM EFFECTS, CONTINUED AURORAL FORCING

5. STORM PEAK AND RECOVERY

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Optical and Radio Observations and AMIE/TIEGCM Modeling of Nighttime Traveling Ionospheric Disturbances at Midlatitudes During Geomagnetic Storms

1. INTRODUCTION

2. IMAGING OBSERVATIONS AND COMPARISON WITH VERTICAL SOUNDINGS

3. CONJUGACY OF STORM -TIME TIDS

4. COMPARISON WITH AMIE/TIEGCM

5. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

Section IV: Ionospheric Gradients, Irregularities and User Needs

A Digest of Electrodynamic Coupling and Layer Instabilities in the Nighttime Midlatitude Ionosphere

1. INTRODUCTION

2. ELEMENTS OF COUPLED INTERACTIVE BEHAVIOR

3. SOURCES OF INSTABILITY

4. DISCUSSION

Irregularities Within Subauroral Polarization Stream-Related Troughs and GPS Radio Interference at Midlatitudes

1. INTRODUCTION

2. OBSERVATIONS

3. DISCUSSION

4. CONCLUSION

DEMETER Satellite Observations of Plasma Irregularities in the Topside Ionosphere at Low, Middle, and Sub-Auroral Latitudes and their Dependence on Magnetic Storms

1. INTRODUCTION

2. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE DEMETER SATELLITE

3. REPRESENTATIVE DEMETER OBSERVATIONS

4. DISCUSSION

Optical and Radio Observations of Structure in the Midlatitude Ionosphere: Midlatitude Ionospheric Dynamics and Disturbances

1. INTRODUCTION

2. DATA PRESENTATION

3. DISCUSSION

Section V: Experimental Methods and New Techniques

Global-Scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD): New Observing Capabilities for the Ionosphere-Thermosphere

1. INTRODUCTION

2. GOLD SCIENCE OBJECTIVES

3. TECHNICAL APPROACH

4. TEMPERATURE RETRIEVALS FROM N2 DISK MAPS

5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Index

Geophysical Monograph Series

Published under the aegis of the AGU Books Board

Kenneth R. Minschwaner, Chair; Gray E. Bebout, Joseph E. Borovsky, Kenneth H. Brink, Ralf R. Haese, Robert B. Jackson, W. Berry Lyons, Thomas Nicholson, Andrew Nyblade, Nancy N. Rabalais, A. Surjalal Sharma, Darrell Strobel, Chunzai Wang, and Paul David Williams, members.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Midlatitude ionospheric dynamics and disturbances / Paul M. Kintner, Jr. ... [et al.], editors.

p. cm. — (Geophysical monograph, ISSN 0065-8448 ; 181)

ISBN 978-0-87590-446-7

1. Ionosphere—Research. 2. Ionospheric storms. 3. Sudden ionospheric disturbances. 4. Space environment. I. Kintner, Paul M.

QC807.5.M53 2008

551.51′45—dc22

2008045394

ISBN: 978-0-87590-446-7

ISSN: 0065-8448

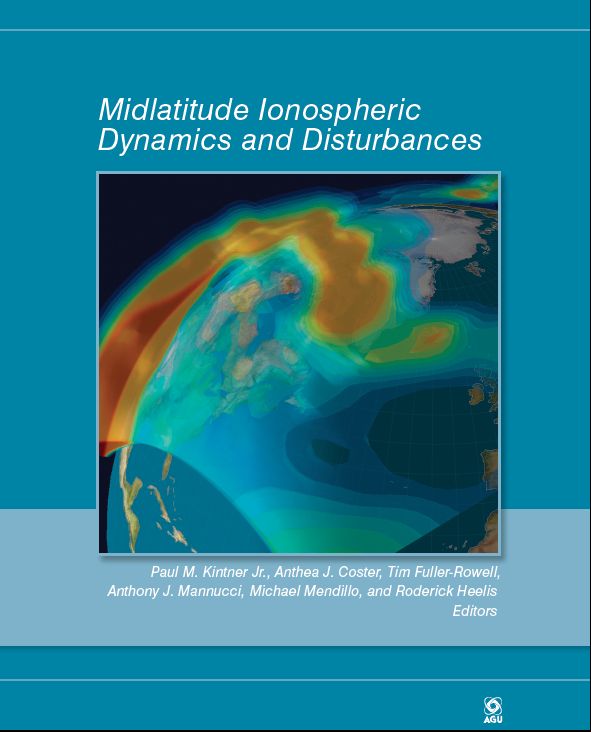

Cover Photo: Isocontours of electron density during the 30 October 2003 storm from University of Bath MIDAS GPS tomography (courtesy of Cathryn Mitchell and Paul Spencer).

Copyright 2008 by the American Geophysical Union

2000 Florida Avenue, N.W.

Washington, DC 20009

Figures, tables and short excerpts may be reprinted in scientific books and journals if the source is properly cited.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the American Geophysical Union for libraries and other users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transactional Reporting Service, provided that the base fee of $1.50 per copy plus $0.35 per page is paid directly to CCC, 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923. 0065-8448/08/$01.50+0.35.

This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for creating new collective works or for resale. The reproduction of multiple copies and the use of full articles or the use of extracts, including figures and tables, for commercial purposes requires permission from the American Geophysical Union.

PREFACE

In September 2002, the NASA-sponsored Living with a Star Geospace Mission Definition Team (GMDT) issued its report entitled “The LWS Geospace Storm Investigations: Exploring the Extremes of Space Weather.” This report identified the mid-latitude ionosphere as a critical component of space weather. Preliminary results from John Foster and Anthea Coster combining TEC measurements from networks of GPS receivers across North America demonstrated for the first time that the response of the mid-latitude ionosphere during magnetic storms was organized. Earlier measurements from scattered sites had identified the positive and negative phases of mid-latitude ionospheric storms, but had not appreciated the organization over continent-size scales. This new model showed promise but it had not yet matured beyond a curiosity.

Nearly three years later, J. Grebowsky organized a session of invited speakers for the Spring 2005 AGU General Assembly to address the science of the original GMDT report. R. Pfaff, T. Fuller-Rowell, G. Lu, L. Paxton and I offered separate viewpoints on the science. At this juncture, the accumulated evidence irrefutably confirmed the preliminary results of Foster and Coster and changed the community viewpoint toward the mid-latitude ionosphere as a quiet and uninteresting region. Other experiments, involving dense arrays of GPS TEC receivers in Japan and imaging of ionospheric air glow, revealed even more complex and fascinating structures with regional length scales in the mid-latitude ionosphere. Global models and simulations were utilized to actively investigate the cause of mid-latitude ionospheric storms. After the session, it was obvious that the 90 minutes available for discussing progress in understanding the midlatitude ionosphere was woefully inadequate.

The organizer, invited speakers, and audience members decided to hold an impromptu meeting late in the afternoon in an empty meeting room. To the small group assembled somewhat haphazardly in New Orleans it was clear that the mid-latitude ionosphere deserved attention as a special region unto itself. A decision was made to propose to AGU a Chapman Conference entitled Mid-latitude Ionospheric Dynamics and Disturbances and I volunteered to lead the effort. A. Coster, T. Fuller-Rowell, A. Mannucci, and M. Mendillo offered to be co-organizers. The conference occurred at Yosemite National Park, California, 3–6 January 2007, and inspired this monograph.

This book is our best attempt to assemble in one place a comprehensive examination of the mid-latitude ionosphere and to convey the spirit of the Chapman Conference. There was substantial debate over the question of what was a mid-latitude ionospheric storm: Was it the auroral zone pushing equatorwards, equatorial convective storms pushing pole ward, or a unique process? In the end, most participants had begun thinking of the ionosphere as responding globally during a magnetic storm. In this view, the daytime mid-latitude ionosphere is the region through which the storm transports huge volumes of ionospheric plasma into the polar caps and onto the night side. It is also the region where inner-magnetospheric electric fields and thermospheric-driven dynamo electric fields and chemistry compete to control the mid-latitude ionosphere. A central theme was that space-based measurements of the ionosphere and thermosphere are required for progress. Resolving these issues is the subject of a future Chapman Conference built upon future measurements of the midlatitude ionosphere.

Paul M. Kintner Jr.

Cornell University

Recent discoveries have demonstrated that the ionosphere responds over regions extending from the equator to the poles during geomagnetic storms and experiences the most extreme changes at midlatitudes. The midlatitude ionosphere was first studied during the “discovery era” of radio physics and space flight 50 or more years ago, but for the past three decades the polar and tropical ionosphere have dominated scientific activity, resulting in the false impression that the midlatitude ionosphere was an uninteresting region of known morphology and well-understood processes. During the past five years, however, the ability to image the ionosphere and thermosphere with large arrays of ground-based GPS receivers and satellite-borne UV imagers changed this viewpoint dramatically and led to the inception of the Chapman Conference on Mid-Latitude Ionospheric Dynamics and Disturbances (MIDD) and to this monograph.

The most dramatic changes in ionospheric content occur at midlatitudes, not at high or equatorial latitudes. The most extreme examples of ionospheric total electron content (TEC) perturbations occur at midlatitudes during geomagnetic storms, where TEC can change by factors of three to ten over the duration of a magnetic storm. The ionosphere responds to magnetic storms over regions extending from the equator to the poles, where huge volumes of plasma are produced and transported polewards. Sharp gradients in ionospheric content, extending thousands of kilometers, are created by unknown factors. These gradients spawn irregularities that together impact users of RF signals, either transiting across or reflecting from the ionosphere. At higher altitudes, dramatic changes in the ionosphere are accompanied by movement and transport of the plasmasphere.

The midlatitude ionosphere is controlled by two largely unconstrained mechanisms: the inner magnetospheric electric field, originating in the heliosphere, and the dynamic properties of the thermosphere. The recent MIDD Chapman Conference brought together three communities to investigate this control: (1) the ionospheric community, which is characterizing and modeling the midlatitude domain, (2) the magnetospheric and solar wind community, which is investigating how inner magnetospheric electric fields map to and transport the midlatitude ionosphere, and (3) the thermospheric community, which is investigating how thermospheric winds and composition control the midlatitude ionosphere. During geomagnetic storms these fields and winds are strongly driven, yielding ionospheric space weather in the form of gradients and irregularities. When these occur at midlatitudes, where the U.S. taxpayer resides, the effects of ionospheric space weather take on special importance, particularly in the area of GPS and aviation.

At the beginning of this monograph, midlatitude ionospheric storms are defined and the historical record reviewed. On the poleward side, the midlatitude ionosphere is bounded by the auroral ionosphere and on the equatorward side by the equatorial ionosphere. To some extent, processes in these two regions enter the midlatitude ionosphere, but processes unique to the midlatitude ionosphere also appear to exist. Alternately, the midlatitude ionosphere may be a plasma source region for the polar cap and the magnetosphere. Addressing the relative significance of these regions and their processes is largely an experimental effort aided by models and visualizations that ingest large quantities of data.

Defining a midlatitude ionospheric storm leads directly to the debate over what causes them. There are two possibilities: external electric fields originating in the solar wind and inner magnetosphere and thermospheric winds. Electric fields within the solar wind are modified by magnetospheric plasma populations as the fields propagate inward and eventually reach low and middle latitudes. The asymptotic behavior consists of shielding the inner magnetosphere from solar wind electric fields, but rapidly changing solar wind electric fields can reach the inner magnetosphere during a period of 1 to 2 hours, before the plasma populations can react. This electric field is referred to as a prompt penetration electric field (PPEF). On the other hand, thermospheric winds also drive the ionosphere, and the equivalent electric fields are referred to as disturbance dynamo (DD) electric fields. Either electric field source could explain midlatitude ionospheric storms, which led at the conference to a spirited debate conducted primarily with models and simulations. The sustaining reason for this controversy is a lack of comprehensive measurements to act as drivers of the models or to distinguish their predictions.

The monograph is organized around the principles discussed above: investigations of midlatitude ionospheric storms, investigations of electric field coupling from the heliosphere and inner magnetosphere, and thermospheric control of the midlatitude ionosphere. In addition, a section on ionospheric gradients and irregularities examines the space weather aspects of the midlatitude ionosphere. Our future understanding of midlatitude ionospheric storms as a part of global ionospheric storms will depend on new experimental techniques based on satellites to resolve the current controversies. This monograph highlights the scientific progress in characterizing the midlatitude ionosphere and the new questions raised by this progress.

Central to the theme of this monograph is the characterization of midlatitude ionospheric storms. The papers in this section cover a broad spectrum of issues in this area, beginning with a general review of ionospheric storms at midlatitudes by Gerd Prölss. This paper provides a brief history of ionospheric storm research, describing how early observations from either a single observatory or from small subgroups of observatories were used to discover the positive and negative phases of ionospheric storms. The positive phase of an ionospheric storm is when the total electron content, TEC, increases early during the storm period. This is followed by a decrease in the TEC during the storm recovery phase (the negative phase). This paper also discusses different possible definitions of “middle latitudes.” One definition has the midlatitudes sandwiched between the equatorward boundary of subauroral phenomena and the edge of the equatorial anomaly peaks. An alternate definition holds that the middle latitudes are a region unaffected by subauroral or equatorial phenomena, at least during quiet or moderately disturbed conditions (e.g., 25 to 55 degree invariant latitude). Prölss concludes his paper with a discussion of the origin of the positive phase of ionospheric storms. He points out that both winds and electric fields are important mechanisms and notes that the question is not which one of these mechanisms is responsible for the positive phase, but rather which of these two mechanisms is more important, especially at middle latitudes.

The next paper, by A. S. Rodger, discusses the midlatitude trough, which is an extremely consequential feature that forms near the boundary of the midlatitudes. The midlatitude ionospheric trough is a region at F-region altitudes, typically a few degrees wide in latitude, where the plasma concentration is usually lower as compared with regions immediately poleward and equatorward. Figure 1 in his paper presents two visualizations of this region. The trough normally lies close to the equatorward boundary of the auroral precipitation and is where the corotation and convection electric fields are oppositely directed (approximately). The trough is a region that is strongly coupled to the spatial and temporal variation of electric fields in its vicinity and thus has important consequences for midlatitude ionospheric storms. During geomagnetically active periods, the detailed morphology of troughs becomes difficult to predict, as the cross-polar cap electric field is usually increasing while the auroral oval is expanding.

The paper by J. Sojka discusses the inadequacies of models in describing the evolution of the distribution of electric fields and neutral winds during ionospheric storm periods in the midlatitudes. In his paper, he presents a simplified convection electric pattern and uses this to drive a physics-based ionospheric model demonstrating how superstorm ionospheric conditions can be generated. He points out that future models that incorporate data assimilation may be able to someday overcome the limitations of present-day empirical and physical models.

The next paper is R. Heelis’s review of our current understanding of low and middle latitude ionospheric dynamics and energetics associated with magnetic storms. The DMSP data shown in Figure 2 of his paper is significant. It clearly indicates that during the large geomagnetic storm of 20 November 2003, magnetic latitudes near 50 degrees, normally associated with the midlatitudes, become fully engulfed in the auroral zone. Furthermore, this figure also shows that near dusk the sunward (westward) flows normally associated with the auroral zone now exist at latitudes as low as 30 degrees. These data illustrate that, under these circumstances, middle latitudes, which are usually dominated by corotation and dynamo fields, may be directly influenced by auroral electric fields and particles. Heelis also points out that it appears prudent to consider the formation and evolution of the TEC enhancements at middle and low latitudes as separate features, even if they may at times be collocated. His conclusions, which agree with those of the earlier papers in this section, are that significant questions remain concerning the role that winds and electric fields play in producing the dramatic midlatitude ionospheric density perturbations observed during major geomagnetic storms.

This paper is followed by a discussion by G. Lu et al. of the global modeling of ionospheric TEC and the role of neutral winds and electric fields in producing enhanced TEC during a moderate geomagnetic storm on 10 September 2005. Her paper shows that, by using realistic time-dependent ionospheric convection and auroral precipitation as input, the Thermosphere Ionosphere Electrodynamics General Circulation Model (TIEGCM) is able to reproduce the large-scale storm features in the electron density, electron temperature, and vertical ion drift observed by incoherent scatter radars (ISRs). The model also captures the temporal and spatial TEC variations shown in the global GPS maps. The agreement in the data-model comparison suggests that using the TIEGCM to investigate which mechanisms have played a significant role in generating the observed storm-time features is a valid approach. The result of this model investigation suggests that the primary cause of the dayside positive storm phase during this moderate geomagnetic storm is the storm-enhanced meridional neutral wind.

The final papers in this section concern recent results. They describe new techniques that are being used to monitor the midlatitude storm features. The first of these new-techniques papers is by M. Meyer and includes a report on observations of features associated with storm-time electric fields: the sub-auroral polarization stream (SAPS). These observations were collected using passive, coherent radar facilities at the University of Washington. The receivers are situated in Washington State and have an effective field of view of the sub-auroral region over southwestern Canada. These passive radars use FM radio waves to observe E-region structures at a range resolution of 1.5 km. Further techniques involving interferometry enable the resolution of scattering volumes in the cross-beam dimension and facilitate the localization of echoes within the radar field of view.

Figure 2 in Meyer’s paper shows a fine-scale wavelike modulation propagating through the SAPS electric field, which is itself drifting (more slowly) equatorward. The period of the modulation observed over a 3-hour period is between 1 and 3 minutes (corresponding to 5–16 mHz). The electric field sub-structures (referred to as sub-auroral ionization drifts (SAIDs) by some authors) appear to be propagating equatorward at an average phase velocity of 415 m/s while the entire channel drifts equatorward at approximately 140 m/s.

The next new technique paper provides a discussion of 4D ionization dynamics by C. Mitchell et al. This paper describes a new observation technique called GPS imaging where the line-of-sight TEC observations from a global network of receivers are inverted into 3D time-dependent maps of electron density. Three large geomagnetic storm periods were studied. In each case, it was observed that the main phase of the storm involves a sudden uplift in F-layer altitude extending across the entire midlatitude region, and that this uplift propagates westward (from Europe to the United States).

Finally, G. Bust reports on another GPS imaging analysis using the 4D imaging algorithm called Ionospheric Data Assimilation Three-Dimensional (IDA3D). His study addresses the question of whether storm enhanced density (SED) midlatitude plasma is due to high altitude transport of equatorial plasma. His study also examines the similarities and differences between the 2003 October 30 and November 20 storms. His analysis suggests that the enhanced plasma in the midlatitude region is an extension of the equatorial anomaly region. However, again in agreement with the other authors in this section, he points out that the relative roles of electric fields, winds, and composition remain to be understood in the context of the detailed formation of the SED. He also raises the issue of another unknown, which is the question of how plasma within the midlatitude bulge region, which is not moving at a high speed, transformed into a tongue of ionization (TOI) that is moving poleward at large plasma velocities.

The papers in this section raise several questions and identify many unknowns in our understanding of midlatitude ionospheric storms. Combining new models with new data sources and new data analysis techniques are all critical next steps to increasing our understanding of how ionospheric storm features are produced. An understanding of the physical forces and their dynamic interactions is required to predict the space weather effects associated with large midlatitude ionospheric storms.

Tsurutani et al. begin this section with a review of the origins of global ionospheric storms from outbursts on the sun to solar wind coupling to the ionosphere. This paper firmly establishes on theoretical and empirical grounds that geomagnetic storms causing significant midlatitude disturbances originate with conditions in the solar wind. Solar coronal mass ejections (CMEs) generally lead to geomagnetic storms if they reach the Earth. The more intense CMEs become “superstorms” with significant midlatitude consequences, especially if the southward magnetic field component has large values (–10 nT or more) that persist for several hours. Increases in solar wind ram pressure (dynamic pressure) are also associated with geo-effectiveness, as are sudden increases in solar irradiance due to solar flares. Intense flares cause short-duration increases in dayside electron density at all sunlit latitudes, known as sudden ionospheric disturbances (SIDs). Tsurutani et al. discuss the impact of the major flare of 28 October 2003, the largest flare ever recorded in the EUV portion of the spectrum. Uncertainties in measuring the transient spectra and in modeling the thermosphere define a difficult modeling problem. How well understood the physical processes that lead to electron density and TEC increases are remains an open question.

Anghel et al. emphasize the important role of electric fields in linking solar wind conditions to ionospheric disturbances. Electric fields are induced over the Earth’s ionosphere by moving plasma clouds. A net Bz southward component is associated with the highest degrees of geo-effectiveness (Ey = V × Bz in GSM coordinates). Dawn–dusk electric fields induced by the heliosphere can “penetrate” (propagate) from high to low latitudes within minutes of reaching the magnetopause. This direct solar wind–ionosphere link is exploited by Anghel et al., who perform a joint statistical analysis of measured ionosphere electric fields and electric fields induced at Earth by the solar wind. Such a joint statistical analysis provides information on the coupling as well as the frequency components in the heliospheric driver itself.

The third paper in this section emphasizes that midlatitude dynamics are strongly affected by physical coupling between the magnetosphere and ionosphere. The J. C. Foster paper discusses recent research by the Millstone Hill group in M–I coupling during dusk-time, including the important role of subauroral electric fields. This paper focuses on storm-enhanced density (SED) and how the SED structure depends on the relative magnitudes of the Earth’s corotation electric field and electric fields in the inner-magnetosphere, which evolve on time scales of tens of minutes during storms. The increased plasma content over a large fraction of Earth is caused by what has been termed the “Dayside Superfountain.” The possibility of a “preferred longitude” for highcontent SED is also suggested by Foster et al. due to the reduced magnetic field in the American sector (also known as the South Atlantic Anomaly).

Verkhoglyadova et al. present data from the Jicamarca incoherent scatter radar that measures electron density at the F2 layer peak (foF2) as a function of time for the 30 October 2003 superstorm. A striking aspect of this superstorm is the enormous depletion of plasma near the equator as the storm progresses through the main phase. Afternoon peak electron densities reduce by a factor of three in about ~1.5 hours during the storm’s main phase. The measured depletion is compared to three separate model runs that produce electron densities that are 50% to >200% larger than measured. A possible reason for the discrepancy between measurements and modeled foF2 is electric field inputs to the model being too low (peak value ~1 mV/m estimated by the dual magnetometer method), since PPEF may attain values of 4–5 mV/m during large storms. Verkhoglyadova et al. conclude with a forward-looking discussion of PPEF modeling and its consequences and call for more sophisticated modeling of PPEF at local dawn.

Brandt et al. explore several elements contributing to the SAPS electric fields and more generally to magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling. This paper uses observations and modeling to study M–I coupling via Region 2 currents from a unique end-to-end perspective, combining solar wind, magnetospheric, and ionospheric data. The Energetic Neutral Atom (ENA) images clearly show a highly asymmetric ring current during the main “driven” phase of the storm. Plasma pressure within the ring current is the driver for closure currents into the ionosphere, and these currents close through a medium with finite conductivity. Brandt et al. present data showing a correlation between high-speed flow in the ionosphere and HENA image intensity. Then they show that ionospheric conductivity distributions strongly modify magnetospheric electric fields and influence particle motions, creating a feedback loop between ionospheric conductivity and electric fields with magnetospheric currents and electric fields.

The next paper in this volume returns to more global considerations. Kikuchi et al. analyze three magnetic storms to further understand a fundamental issue of global M–I coupling: How do electric fields penetrate globally into the ionosphere? They find that equatorial DP2 currents respond nearly instantaneously to increased auroral electrojet activity (AE index). This global-scale coupling is viewed as being due to an electric field propagation in the zeroth-order transverse mode of the Earth–ionosphere waveguide. Kikuchi et al. show that the magnitude and sign of equatorial DP2 currents are sensitive indicators of the relative roles of penetration versus shielding effectiveness and that, in the tightly coupled M–I–T system, magnetospheric current systems will generate ionospheric electric fields mapping back out to the magnetosphere, suppressing or enhancing the ring current.

The final paper in this section, by Garner et al., is a reminder that the ionosphere is not coupled solely to the solar wind and magnetosphere—it is part of the thermosphere. During geomagnetic disturbances, thermospheric modification is known to occur via high-latitude Joule heating; global circulation changes as a consequence. Ion-neutral drag generates electric fields via the disturbance dynamo mechanism. Garner et al. investigate the “second-order” impact of the neutral-wind dynamo electric fields on the Region-2 current system. The significance of this science question is perhaps highest during periods with multiple storms, when geo-effective solar wind conditions influence a previously disturbed thermosphere (so-called “preconditioning”). A model is used to map the electric fields generated from the disturbance dynamo electric field out to the magnetosphere. The model used is the Thermosphere–Ionosphere–Mesosphere Electrodynamics General Circulation Model (TIME-GCM), a coupled thermosphere–ionosphere model that self-consistently includes ionospheric electrodynamics.

The cause of long-lived depletions in the midlatitude ionosphere during recovery from a geomagnetic storm, the so-called negative phase, has long been thought to be a consequence of neutral composition changes. Apart from the plasma structure associated with the sub-auroral trough or depletions associated with the high-velocity plasma streams associated with SAPS, neutral composition changes still remain the most likely explanation. Crowley and Meier review the neutral composition theory for the negative phase by comparing in detail the numerical modelling results with relatively recent and fairly extensive observations of the O/N2 ratio from the GUVI instrument onboard the TIMED spacecraft. They show that numerical models simulate the storm-time thermospheric neutral composition changes quite well, except for details in the response and recovery time-scales.

Neutral composition changes arise from adjustment of the global circulation following the impulsive injection of energy at high latitudes. The dynamical changes are reviewed by both Meriwether and Shiokawa et al. from the observational perspective and by Fuller-Rowell and Richmond from the modelling side. Meriwether’s review indicates that over the last 20 to 30 years, quite an extensive database of observations has been assembled from the combination of ground-based and space-based observations. Much of this database has been captured in the latest Horizontal Wind Model (HWM) by Emmert et al., which is much improved over the earlier versions and which explicitly includes a Disturbance Wind Model (DWM) component. Although becoming more extensive, thermospheric neutral wind observations still have many holes in their coverage and have rarely been taken in conjunction with the related plasma and electrodynamic components. Consequently, although the numerical results presented by Fuller-Rowell and Richmond appear to capture many of the observed dynamical features, such as the wave features presented by Shiokawa, the realism of some of the thermospheric dynamo characteristics, in particular, the apparent rapid dynamo response, have yet to be confirmed. Thus, ambiguity remains in separating the prompt penetration and disturbance dynamo, particularly on the night side. This ambiguity has prompted the need for coupled models of the thermosphere–ionosphere–plasmasphere and the inner magnetosphere, as was presented by Maruyama at the conference.

The thermospheric dynamics and neutral composition response to geomagnetic storms is strongly influenced by the intensity and time dependence of the energy injection at high latitudes. A good indicator of the amount of energy injected is the increase in neutral temperature and density globally. Burke et al. attempt to quantify this integrated energy source by direct comparison of the geomagnetic indicators, such as Dst and solar wind parameters, with observations of neutral density from the CHAMP satellite. They concluded from energy budget considerations that the solar wind–magnetospheric–ionosphere pathway is the primary route and that the path through the ring current is not the main driver of neutral thermospheric density change.

The relationship between neutral density and composition change is explored by Immel et al. They show that the physics of density change and neutral composition, although ultimately driven by the same high latitude heating, are different; and that although the two are closely related, sometimes due to the common source, at other times the two parameters can be quite different. The difference in the physics is that density responds to heating and thermal expansion of the atmosphere whereas the O/N2 ratio change observed by a GUVI-type instrument requires a change in the global circulation. Fedrizzi et al. show a second consequence of thermospheric expansion: It can raise the height of the F layer due to the vertical winds associated with expansion. Further, they separate and quantify the relative contribution of expansion and horizontal wind in changing the height of the ionosphere at midlatitude during a storm.

Spatial ionospheric perturbations at midlatitudes fall roughly into several categories. At the longest length scales (50–200 km), features associated with equatorial convective storms can propagate poleward to midlatitudes such as Hawaii. At mesoscales (100 km), traveling ionospheric disturbances (MSTID) with a northwest to southeast orientation dominate and are sometimes associated with magnetic storms. At yet shorter scales (<1 km), irregularities occur on background gradients with several possible origins.

Makela et al. discuss optical and GPS observations of gradients and scintillations at Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Using 630-nm observations of night glow, they demonstrate that the plumes typically associated with equatorial convective storms occur over and to the north of Hawaii. They are primarily oriented along magnetic field lines and tilt westward with time because of shear and conductivity gradients. These structures frequently exhibit braided behavior on their western flanks, which Makela et al. ascribe to the gradient drift instability produced by thermospheric winds blowing across ionospheric gradients. Using the same 630-nm imaging technique, they then examine ionospheric structures over Puerto Rico where MSTID are found. These structures are aligned northwest to southeast and propagate mostly to the southwest, but occasionally in a northeast direction. The peculiar orientation of the MSTID is explained by the Perkins instability, although the local linear growth rate is too small to be significant.

This problem was considered by Tsunoda et al., who considered E-region coupling to the F region. They examine the “E-layer” instability, which is plane wave fluctuation in altitude in the presence of a neutral wind shear. These fluctuations have the largest growth rates at propagation directions, very similar to the Perkins instability but the growth rates are larger. Coupling of the E and F regions, driven by shear in the zonal wind, leads to altitude fluctuations with the correct pattern and scale lengths to explain MSTID.

Pfaff et al. present electric field fluctuation and density data from the Demeter satellite in circular orbit at 710 km altitude. They showed that, during the main phase of magnetic storms, the ionospheric density increased dramatically at midlatitudes by a factor of 10–100 at the altitude of Demeter. Simultaneously, these same regions exhibited electric field fluctuations over the frequency range of 1–500 Hz, which correlated well with regions of depleted ionosphere and ionospheric gradients. Furthermore, this behavior was similar on both the dayside and night side. Pfaff et al. also note that the midlatitude ionospheric disturbances are limited to about 6 hours during the main phase of a magnetic storm. During this same period, the equatorial ionosphere rises above the altitude of Demeter, and Pfaff et al. conclude that an eastward electric field is responsible for the vertical motion.

Mishin et al. propose an alternate explanation for midlatitude irregularities, using DMSP data to note the relationship between electric field and density fluctuations, the inner edge of the ring current, and subauroral polarization streams (SAPS). They call the electric field “supauroral polarization stream wave structures” or SAPSWS. The SAPSWS are found on the inner edge of the ring current and within SAPS regions. They propose that SAPSWS are generated by field-aligned currents on the inner edge of the ring current that are unstable to current convective instabilities. The SAPSWS, acting on plasma density gradients, then produce irregularities responsible for scintillations at UHF and L-band frequencies.

J. Foster has summarized the controversy over the origin of midlatitude dynamics and disturbances with the statement, “What we see depends on how we look.” In “looking” at the midlatitude ionosphere, two big challenges exist. First, there are no continuous global scale measurements characterizing the state of the midlatitude ionosphere and its obvious connections to the low-latitude and high-latitude ionosphere. Second, there are no global or in situ measurements characterizing thermospheric winds and composition. Ground-based measurements can be helpful. For example, daytime electric fields in the tropics can be inferred from magnetometers, but midlatitude electric field measurements will require in situ electric field measurements with an accuracy of better than 1 mV/m. Dual frequency GPS receiver networks have also been helpful in identifying the global nature of ionospheric storms, especially at midlatitudes, but gaps in coverage over the oceans, the tropics, and polar regions and the limitation of only sensing TEC leave major questions unaddressed.

At regional and shorter-length scales, our understanding of the generation of midlatitude ionospheric gradients and irregularities is less well advanced, with characterization still being an important issue. MSTID observed in the Japanese sector with dense GPS arrays and observed in Puerto Rico with ground-based airglow cameras have revealed this phenomenon. Questions about their global distribution, the importance of E-region coupling through thermospheric wind shear, the implications of conjugate behavior, the origin of TEC fluctuations, and the origin of Fresnel scale irregularities are just now being addressed, with no consensus on the basic physical process involved.

Ionospheric storms unquestionably originate in the heliosphere, driven by solar processes. The details of how the ionosphere responds depend critically on magnetospheric properties and the thermospheric history. Yet, perhaps one of the most significant issues addressed by this monograph is that the ionosphere does not react just passively to driving forces from above. Changes in ionospheric conductivity react back on ring current pressure gradients and modulate ring current development. SED structures flowing poleward through the midlatitude may be a reservoir, providing heavy ions to the magnetosphere.

Controversy over the origin of ionospheric storms can only be resolved by measurements that provide continuous globalscale characterization complemented by in situin situ