Contents

Notes on contributors

Chapter 1: Introduction

References

Chapter 2: Understanding vulnerability

Introduction

Defining vulnerability

Vulnerability and healthcare

Professional definitions of vulnerability

Different theoretical explanations for vulnerability

Models of vulnerability

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 3: Power, discrimination, and oppression

Introduction

Defining oppression and discrimination

The PCS model of oppression

The role of power

About power – what is it?

Two types of power?

The effect of power

The abuse of power

Prevention of abuse

Theories of power

Perspective one: Traditional ‘pluralist’ theories

Sources of power

Perspective two: Marxist and ‘system’ theories of power

Lukes and the three faces of power

Perspective three: The ‘dispersed power’ perspective

Example of disciplinary gaze in medical and nursing context

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 4: Processes of oppression

Introduction

Overview of the processes

Stereotyping

Stigmatisation

Marginalisation

Invisibilisation

Infantilisation

Medicalisation

Welfarism

Dehumanisation

Trivialisation

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 5: Professional culture and vulnerability

Introduction

Professional socialisation

Personal values

Professional values

When things go wrong

Advocacy, empowerment, and anti-oppressive practice

Thompson’s PCS model and the influence of professional culture

Vulnerability and ‘belongingness’

Increasing vulnerability through ritual and routine work practices

Horizontal violence

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 6: The social construction of vulnerability

Introduction

Social constructionism

Discourses and vulnerability

Social construction of identity

Essentialist views of identity

Essentialism and stereotyping

Essentialist perspectives and vulnerability

Social identity, oppression, and power

Multiple identities

Social identity and practice

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 7: Psychological perspectives of vulnerability

Definition: Psychology

Psychology advocate or detractor?

What can psychology offer practitioners committed to reducing discrimination and oppression?

Subjective perception

Making judgements and attributions

Availability heuristic

Prejudice: Psychological perspectives

How has prejudice been defined and explained by psychology?

Prejudice as a personality trait

Social categorisation

Stereotyping

Intergroup relations

Reducing prejudice

A summary of some other psychological approaches pertinent to vulnerability

Lack of control

Learned helplessness

Process of learned helplessness

Resilience and hardy personality

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 8: Psychosocial experiences and implications of vulnerability

Introduction

What is sociology and its possible use in exploring vulnerability and oppression?

Historical explanations

Exploitation explanations

‘Othering’

The organisational level

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 9: Working to reduce vulnerability

Introduction

What is anti-oppressive practice?

Personal level strategies

Cultural level strategies

Structural level strategies

Conclusion

Links to other chapters

References

Chapter 10: Conclusion

Final thought

Where can I get further help or advice?

References

Index

You must be the change you wish to see in the world.

Mahatma Ghandi

This edition first published 2013 © 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Understanding vulnerability : a nursing and healthcare approach / edited by Vanessa Heaslip and Julie Ryden.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-67136-8 (pbk.)

I. Heaslip, Vanessa, 1974– II. Ryden, Julie, 1961–

[DNLM: 1. Ethics, Nursing–Great Britain. 2. Coercion–Great Britain. 3. Nurse-Patient Relations–ethics–Great Britain. 4. Quality of Health Care–ethics–Great Britain. 5. Vulnerable Populations–psychology–Great Britain. WY 85]

RT82

610.7306′9–dc23

2013009647

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Cover image: Photoscan/Shutterstock

Cover design by Design Deluxe

This book is dedicated to all of the people who shared their stories and experiences with us; we hope that by allowing us a window into their experiences it will enable each of us to reflect upon our practise and commit to ‘making a difference’, so that people’s experiences of vulnerability are reduced.

We would like to express our thanks to our families for their ongoing support during this process, and Angela Warren who kindly undertook some proofreading for us.

We are a group of experienced professionals, academics, and educationalists who have expertise in the exploration of vulnerability from both an educational as well as a research perspective. We have developed and run a variety of educational units at different educational levels for nurses, paramedics, and community workers. We believe that an understanding of vulnerability is essential in providing humanistic person-centred care.

Sid Carter, PHD, MSc, BA, PGCEA, RNLD, teaches and researches in the areas of learning disability and psychology at Bournemouth University. He is a learning disability nurse and thus has a long-term interest in the processes of discrimination and vulnerability. Sid’s current research includes investigating methods to enhance the involvement of young people with learning disabilities in the services they use.

Karen Cooper, MA (Health and Social Care Education), BNS (Hons), RGN, Dip NS, has 30 years clinical experience within medicine and care of the older person and, ultimately as a Ward Manager in a rehabilitation setting. She moved into education in 2005 initially as a Practice Educator and is currently a lecturer in adult nursing. Areas of academic and research interests are in practice learning, assessment, and mentorship in relation to practitioners’ personal and professional practice.

Nikki Glendening, PGDip, BSc (Hons), RN, RHV, RNT, is a senior lecturer in adult nursing at Bournemouth University. She is a qualified and registered nurse, health visitor, and nurse educator as well as a Specialist Public Health practitioner. Areas of academic and research interest include epistemological and psychological experiences of higher education among nursing students, including the experience of student vulnerability in both education and practice.

Vanessa Heaslip, MSc (Health and Social Care Education), BSc (Community Nursing), DipHe Nursing, is a Senior Lecturer in adult nursing; her clinical background was as a District Nurse and specialist practitioner for older people. She is aligned to the Society and Social Welfare Academic Community within Bournemouth University, due to her research interests regarding marginalised, minority groups whose voices are often not heard. Her current PhD study explores experiences of vulnerability from a gypsy/travelling perspective. Other research work has centred on vulnerability as well exploring the human dimension of care.

Julie Ryden, MSc (Psychotherapy), BSc (Hons) (Nursing), PGCEA, Dip DN, RGN, is a Senior Lecturer at Bournemouth University with a nursing background as a District Nurse. Her academic and research interests have always focused upon the experiences of minority groups, anti-oppressive practice, and discursive constructions of vulnerability. Additionally, the interpersonal and human dimension of practice is a key interest.

Janet Scammell, DNSci, MSc (Nursing), BA (Social Science), Dip NEd (London), SRN, SCM, is a registered nurse by background. She has over 20 years’ experience as a lecturer and educational manager with under-graduate and post-graduate students in nursing. Janet also facilitates inter-professional education for health and social care students and has led research projects in this area. She is currently an associate professor in education within the School of Health and Social Care at Bournemouth University. Janet’s research interests are two-fold: practice learning and ethnicity and health care practice, including workforce considerations.

Gill Calvin Thomas, MA Ed., is a qualified, registered social worker, who has worked with older adults, younger adults with physical disability and with adults living with HIV/AIDS within a local authority setting. She is a qualified practice educator and is a senior lecturer in practice learning for the BA social work programme in Bournemouth University. Areas of academic and research interests are in service user involvement within practice learning and the experience of BME students in their practice placements in a predominantly white, rural environment.

Chris Willetts lectures in the School of Health and Social Care at Bournemouth University, in subject areas such a Vulnerability, Social Exclusion and Discrimination, and Anti-Oppressive Practice to undergraduate nurses, social workers, and community development workers (amongst others). He also has professional experience in working with children and adults with learning difficulties in a range of health and social care settings.

To be a nurse, midwife or care giver is an amazing role. There is hardly any intervention, treatment or care programme in which we do not play a significant part. …We support the people in our care and their families when they are at their most vulnerable and when clinical expertise, care and compassion matter most.

(DoH 2012a: 4)

Vulnerability is a key quality that all of us as health carers will encounter in the people we work with. To be a nurse, midwife, or carer working with such individuals is to have a privileged role within society, a role which demands that we exercise that privilege with responsibility, care, and compassion. We are aware that there are numerous examples of excellent care that people experience everyday within the National Health Service (NHS). It is our experience of working with colleagues and students that most people enter the profession with a desire to enhance the lives of individuals with whom they are working, to reduce their level of vulnerability, as well as an on-going commitment to enhancing the nursing profession and the NHS.

However, we are also aware that there are examples of poor quality care experienced. The recent Winterbourne View review (Flynn 2012) and Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust enquiry (Healthcare Commission 2009 and Francis 2010) have identified that some individuals who find themselves receiving care, can and have, received degrading, inhumane treatment by those paid to care for them. The highly publicised Winterbourne View review identified clear examples of horrific, abusive practices that appeared to be woven into the culture of the home. Whilst this case is a relatively rare occurrence in healthcare, there have been a number of recent examples highlighting the provision of poor quality care in health and social care settings (DoH 2008, Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman 2011, Commission on Dignity in Care for Older People 2012). In addition, the Mid staff NHS Trust review by Francis (2010) presented detailed accounts of poor quality care which were often linked to fundamental aspects of care such as nutrition and hydration, continence, privacy and dignity, personal care, and pressure area care. The findings are of great concern to anyone in a caring role and reflect a misuse and abuse of the privileged position we are given. As with the Winterbourne View review, it also transpired that the personal actions of practitioners were compounded by the culture of the organisation. Therefore, when examining quality of care and the vulnerability of patients, clients, service users, or families, it is evident that we need to consider both the personal interactions between those individuals and healthcare practitioners as well as exploring the cultural aspects of the care environment. This book offers that breadth of examination of the topic, and also goes further by exploring some of the structural issues which affect vulnerability.

Nationally there are also structural factors that impact upon quality of care. There has been a drive within the NHS to provide evidence-based standardised care, and this has largely been achieved through the development of care pathways such as Liverpool Care Pathway (NICE 2004) and #Neck of Femur Care Pathway (National Clinical Guidelines Centre 2011). However, there is the possibility that by focusing upon ‘standardised’ approaches to care, it could be at the expense of personalised care – responding to the condition rather than the individual. In addition, there is also a focus nationally on meeting targets within the NHS (DoH 2011); this can result in people being thought of as a number within a service rather than as an individual who is unwell. This demonstrates how structural factors can also contribute to the care experienced by individuals within a service; indeed, this is one of the main criticisms of the Francis Review (2010), which highlighted that people must always come first:

… if there is one lesson to be learnt, I suggest it is that people must always come before numbers. It is the individual experience … that really matters. (Francis 2010: 4)

Because of such high-profile cases identifying poor quality care in the NHS and private care organisations, there has been an increased focus nationally on identifying and promoting the core values of the NHS which were published as a part of the NHS Constitution (DoH 2012b). These core values include:

We believe that this book has something to offer the reader in relation to each of these core values and can enhance the readers’ depth of understanding of each value. A focus upon providing individualised, person-centred care is central to ensuring that the core values of the NHS are met within healthcare; this book will enable you to understand some of the factors that occur at the personal, cultural, and structural level which can inhibit the delivery of person-centred care. The last value ‘everybody counts’ reflects the fact that we live in a diverse society and healthcare practitioners must be equipped for this; yet numerous reports (Mencap 2007, DoH 2008, Michael 2008, Healthcare Commission 2009, Equalities and Human Rights Commission 2010) have highlighted that individuals from diverse backgrounds do not always experience high-quality care. However, professional codes of conduct assert that healthcare practitioners should provide anti-discriminatory practice (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008). Whilst educational preparation for the professional role will address such issues, there is also a potentially flawed assumption that individuals enter their preparation as ‘an empty book, waiting to be written’. However, individuals enter their professional programme of training and practice having already been exposed to a wide variety of perceptions and having experienced a diversity of life experiences that may affect their ability to provide anti-discriminatory care without further time and attention to those perceptions. This book provides readers with the opportunity to critically question their individual and collective practices and beliefs and to do so at a time and place of their choosing. A key message of the book is that there should be no fear attached to such critical reflection; there are no recriminations. Indeed, it is the hallmark of a professional to be able to reflect and learn, rather than turning away from such opportunities.

Government strategy has traditionally considered vulnerability from the perspective that particular ‘groups’ of people who by reason of age, ethnicity, disability, and health status are deemed to be more vulnerable to harm than the rest of society. This book takes the view that such a perspective not only imposes vulnerability on members of these groups regardless of their individual situation and thus may deny their individual difference and experience, but it also obscures the potential vulnerability of other individuals who do not fit within these traditional categories but may still be feeling vulnerable. It is our contention that vulnerability is a ‘condition humana’ (Kottow 2003: 461), which is a potential experience for all people. In this way, the book encourages its readers to see vulnerability in its widest sense, and thus enhances their ability to address and reduce vulnerability for all their clients, not just particular groups of clients. Equally it encourages readers not to assume that an individual is vulnerable just because they can be categorised in a ‘vulnerable group’. This book aims to open the readers’ eyes to the individuality of each client, seeing the person for who they are, rather than making false assumptions based on a tick box mentality. Thus, readers may expand their understanding of the concept of ‘individualised, person-centred care’.

Another key difference in the book’s underpinning philosophy comes from our belief that vulnerability is a socially constructed phenomenon, and that vulnerability is created not by the individual’s personal qualities but by the world they inhabit. This follows the social model of disability (Oliver 1983), in seeing vulnerability as being the result of the environment the person lives in, consisting of attitudes, cultural beliefs, media images, power, strategy and policy, dominant discourses, and other factors. It is our contention that these factors create and construct the experience of vulnerability to an equal or greater extent than any condition or life experience. Through this text, these factors are explored in some depth, and their particular impact upon vulnerability is explored throughout the book.

This book is useful for all healthcare practitioners (students, qualified practitioners, and unqualified practitioners) that are committed to providing person-centred care from a variety of different professional specialties (nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, paramedic science, operating department practitioners, and community workers). In addition, this book can also be used within the undergraduate nursing curriculum to support the essential care clusters identified in the Standards for Re-registration Nursing Education (NMC 2010). We believe that this book can assist practitioners in understanding the wider, human experience of vulnerability. A key strength of the book is its inclusion of people’s voices, thus offering the lived experience of vulnerability which we feel is central to understanding how care is experienced by others. These lived experience accounts are from our personal and professional practice, together with experiences that have been shared by other colleagues. In order to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the individuals, names and circumstances have been changed, and some accounts have even been constructed from collations of several stories. This provides both the foundation for a critical examination of the social construction of vulnerability as well as a constant sense of the ‘real world’ to illustrate and bring to life the theoretical issues under discussion.

This book, we hope, will assist you in developing your thinking and enhancing your practice. As such the book challenges you to reflect throughout on your own contribution to vulnerability and the impact of the healthcare environment in which you work. Just a note regarding terminology: within the book a variety of terms have been used to denote people who experience care (patient, service user, client, people, individual), likewise a variety of terms have been used to denote people who provide care (carer, practitioner, nurse, care giver, health carer), and this has occurred in order to reflect the widest diversity of care and care settings.

Commission on Dignity in Care for Older People (2012) Delivering Dignity: Securing Dignity in Care for Older People in Hospitals and Care Homes. Available from http://tinyurl.com/cque4ox [accessed on 31 July 2012].

Department of Health (DoH) (2008) Confidence in Caring – A Framework for Best Practice. Department of Health, London.

Department of Health (2010) Equity and Excellence – Liberating the NHS. Department of Health, London.

Department of Health (2011) The NHS Outcomes Framework 2012/13. Department of Health, London.

Department of Health (2012a) Developing the Culture of Compassionate Care; Creating a New Vision for Nurses, Midwives and Care-Givers. Department of Health, London.

Department of Health (2012b) NHS Constitution. Department of Health, London.

Equalities and Human Rights Commission (2010) How Fair is Britain? Available from http://wwwequalityhumanrights.com/key-projects/triennial-review/full-report-and-evidence-downloads/#How_fair_is_Britain_Equality_Human_Rights_and_Good_Relations_in_2010_The_First_Triennial_Review. [accessed on 20 October 2010].

Flynn, M. (2012) Winterbourne View Hospital – A Serious Case Review. South Gloucestershire Council. Available from http://hosted.southglos.gov.uk/wv/report.pdf [accessed on 31 October 2012].

Francis, R. (2010) Independent Inquiry into Care Provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005 – March 2009. Stationary Office, London.

Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (2008) Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics. Available from http://www.hpc-uk.org/aboutregistration/standards/standardsofconductperformanceandethics/ [accessed on 31 October 2012].

Healthcare Commission (2009) Investigation into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. March 2009, Available from http://www.nmc-uk.org/Publications/Standards/The-code/Introduction/ [accessed on 24 September 2010].

Kottow, M. (2003) The vulnerable and the susceptible. Bioethics, 17, 5–6, 460–471.

Mencap (2007) Death by Indifference. Available from http://www.mencap.org.uk/campaigns/take-action/death-indifference [accessed on 24 September 2010].

Michael, J. and the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities (2008). Healthcare for All. Available from http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_099255 [accessed on 15 October 2010].

National Clinical Guidelines Centre (2011) The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults; Methods, Evidence and Guidance. National Clinical Guideline Centre, London.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2004) Guidance on Cancer Services Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. National Institute for Clinical Excellent, London.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2008) The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Nurses and Midwives. Available from http://www.nmc-uk.org/Publications/Standards/The-code/Introduction/ [accessed on 8 July 2012].

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2010) Standards for Pre-Reg Education. Nursing and Midwifery Council, London.

Oliver, M. (1983) Social Work with Disabled People. Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2011) Care and Compassion? Report of the Health Service Ombudsman on Ten Investigations into NHS Care of Older People. Available from http://tinyurl.com/clmnu32 [accessed on 27 July 2012].

This chapter will introduce the concept of vulnerability. It will begin by looking at dictionary definitions and develop to explore the link between vulnerability, health, and healthcare by presenting the different ways in which people are viewed as being vulnerable. The chapter will then continue by exploring the differing theoretical explanations of the concept of vulnerability as well as the implications for healthcare practice. Throughout the chapter, readers will be urged to recognise the importance of practitioners having an awareness of vulnerability, and how in their daily practice they can either contribute or reduce a person’s experience of feeling vulnerable.

Little et al. (2000) argue that vulnerability has been studied less than it merits considering the stories of patients and healthcare workers who often identify it as a central theme in the healthcare relationship. Few studies have explored the use of the term vulnerability in healthcare; one such study was by Appleton (1994) who explored health visitors’ perceptions of vulnerability in relation to child protection and identified a lack of consensus and clear definition of the term.

Therefore, before we can explore this concept further, some clarification of the term is required. For example, dictionary definitions identify multiple perspectives:

A common factor in each of these definitions is the notion of harm which denotes a holistic experience as well as a danger or threat to the person. The Latin root of the term vulnerability is ‘vuln’ which means wound or ‘vulnare’ meaning to wound. This supports this sense of harm and wounding which is implied by the dictionary definitions. Now let us consider what this experience means in reality (Box 2.1)

You may have written about times in which you were frightened or felt a lack of control. Indeed, control is a theme that is closely linked to the experience of vulnerability, in that the less control we have over an experience the more vulnerable we may feel, and conversely the more in control we feel we are the less vulnerable we feel. When I think about my own experiences of feeling vulnerable, it is often in situations where I feel out of my depth, where I do not know what will happen, or where I feel isolated and alone.

If we think about times we have felt vulnerable, some of these may have been during periods of ill health or when we have been patients. The NMC (2002) identify that people can experience feeling vulnerable whenever their health or usual function is compromised; thus, vulnerability increases when they enter unfamiliar surroundings, situations, or relationships. Before we go on any further, please read the case study of Peter (Box 2.2).

Often as practitioners, we can forget what it may feel like to be admitted to hospital or how strange this experience may be for someone. In some ways, an admission to a hospital or a care setting can appear to the individual as though they have been transported to an alien world. Thinking of Peter and his story, please read Peter’s perspective (Box 2.3).

Thinking about Peter’s story from this perspective makes it easier to see why he may feel wounded or feel a fear of harm and especially points to a lack of control affecting his vulnerability. Often in doing our jobs, I think we forget about what the experience must feel like for the person at the receiving end of care. In hospitals and care environments, there are different smells and noises, and even the language that patients hear but maybe do not understand; this can be especially more challenging if English is not the patient’s first language. In this alien world, patients have to share personal intimate experiences with a stranger, telling them about things they may never have shared with another human being before (such as their bowel habits). They have to remove their clothes and may even have to have a stranger touching them intimately, exposing their body. For the majority of patients, the only privacy they are afforded is a curtain, and how many times have healthcare practitioners entered a curtain that is closed without asking the patient if it is okay or warning them they are about to enter. It is perhaps unsurprising when considering this that patients may experience feeling vulnerable within a healthcare setting. This coupled with fear and maybe a lack of knowledge and understanding about their health issue can perpetuate the feelings of vulnerability.

There is evidence that unthinking and unquestioning practice does sometimes occur in healthcare which could increase an individual’s propensity to experiencing vulnerability. For example, there is a tendency in healthcare to abbreviate and focus upon the illness or condition (e.g. #NOF, MI, dementia, acopic, Parkinson’s, to name a few) which results in a person losing their identity, and this will be explored further in Chapters 4 and 6. We may question how this increases a person’s likelihood of feeling vulnerable, yet the Confidence in Caring Report (DoH 2008) identified that patients were less confident about being cared about as individuals than concerns they had about their clinical care. There is further evidence of this lack of caring within the Health Ombudsman Report (Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman 2011) which included quotes from relatives such as:

Our dad was not treated as a capable man in ill health, but as someone whom staff could not have cared less whether he lived or died (Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman 2011: 2)

from the moment cancer was diagnosed my dad was completely ignored. It was as if he did not exist he was an old man and was dying (Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman 2011:16).

What these quotes demonstrate is how through unthinking practice staff actually increased the vulnerability of the clients and their families by not focusing upon the individual and their needs. These are extreme cases of how staff increase the vulnerability of clients within their care, but there are more subtle ways, see Alice’s case study (Box 2.4).

As a practitioner working in a busy environment, this scenario may seem insignificant and that Alice could easily have chosen one of the sandwiches on offer. However, to Alice this was really important, as she had never eaten white bread in her life and to her, the fact that the staff did not appear to care about her and her choices may have led her to question what else she will have little control over in the care environment. In this case, a lack of choice increased Alice’s experience of feeling vulnerable. It can be argued that in healthcare, choice is still largely limited as the health service remains predominately based around the needs and ease of the staff and organisation (service led) rather than the needs of the person (needs led). Indeed, if the service was truly needs led, then the nurses could have simply rung the catering department to ask for a brown ham sandwich.

Therefore, in the context of healthcare, vulnerability has to be viewed as an overarching concept which contributes to, and results from, a range of personal, family, societal, and political factors (Shepard and Mahon 2002). This identifies a much wider, more holistic perspective than the dictionary definitions, which tend to focus upon individual characteristics of being liable to harm. Appleton (1994) agrees and notes that vulnerability is caused by a combination of medical, psychological, social, and cultural factors. Thus, it can be argued that vulnerability has to be considered holistically and contextually.

There are health implications of vulnerability which can include both physiological and psychological implications for clients (Rogers 1997) (Table 2.1). Feeling vulnerable has a profound impact upon psychological well-being and can induce feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and loss of control. These psychological feelings impact upon the body physically, which can lead to both increased morbidity and mortality. It is therefore vital that we as practitioners understand how and why patients may experience feeling vulnerable, so that we can mitigate these experiences. By having an understanding of vulnerability, it also enables us to ensure that we do not inadvertently create feelings of vulnerability in others or perpetuate their vulnerability through our daily practice.

Table 2.1 Health implications of vulnerability (Rogers 1997).

| Physiological effects of vulnerability | Psychological effects of vulnerability |

|

|

Whilst not written about extensively in the professional literature, there are some key definitions of vulnerability. Phillips (1992, cited in Rogers (1997: 65)) defines vulnerability as ‘susceptibility to health problems, harm or neglect’. Let us just take a moment to unpick this definition in more detail. Susceptibility to health problems could either be caused by physical (genetic predisposition), psychological (mental illness, fear, or lack of control), or sociological (lack of access to healthcare or financial) factors, thus calling for a holistic interpretation of the danger or threat. Likewise, susceptibility to harm could also be influenced by physical, social, or psychological factors. It is also really important to remember that the threat may be real or perceived and both can contribute to an individual’s experience of feeling vulnerable. For example, there may be two men living on the same street; one feels vulnerable due to a fear of crime and the other does not. The fact that only one of the two gentlemen feels vulnerable does not diminish his experience of it. Vulnerability therefore is similar to the experience of pain, in that it is exactly what the individual experiencing it says it is, and they experience it when they say they are (McCaffery 1968).

In addition, vulnerability is not a dichotomous experience, by that I mean you are either vulnerable or you are not, rather it is situational (Rogers 1997), in that a person who is not particularly vulnerable in one environment may feel highly vulnerable in another, and this could be linked to the amount of control one has over the situation. This situational perspective of vulnerability can help us to understand how individuals that may not be vulnerable may experience feeling vulnerable when they enter healthcare, especially as the amount of control clients have in a healthcare situation is limited, as we explored earlier.

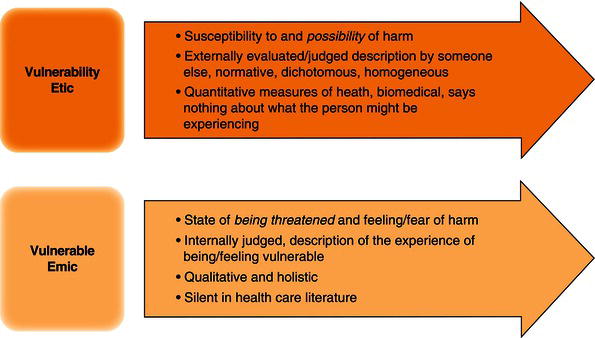

Figure 2.1 Spiers (2000) etic and emic perspectives of vulnerability.

However, when we think of vulnerability in healthcare we most typically think of vulnerable groups in society (Box 2.5).

Within your list, you may have noted groups such as older people, children, people with a mental illness, individuals from ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and people who are homeless. This is because in healthcare the term ‘vulnerability’ is often used as an external judgement to an individual or group that may be susceptible to ill health. The work by Spiers (2000: 716) can help us to understand this in more depth; Spiers makes a distinction between the ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ perspective (Figure 2.1).

The etic perspective of vulnerability relates to the ‘susceptibility to and possibility of harm’. This is externally evaluated or judged by others (e.g., healthcare practitioners) and reflects the normative or professional perspective. This approach focuses upon groups of people and identifies that vulnerability is dichotomous (you are either vulnerable or you are not) and that everyone in that group is the same (homogenous); these judgements are often based upon quantitative measures of health. Many of the clients you identified in Box 2.5 (where you had to list vulnerable groups) would be based upon this normative etic perspective of vulnerability, which focuses upon groups in society with poorer health outcomes. Older people are often identified by practitioners as a vulnerable group due to the increased likelihood of ill health and mortality, yet it has to be questioned whether vulnerability is an inevitable consequence of ageing. It can be argued that ageing is not a dichotomous experience (e.g. that all older people have the same experience) but an individual one; for example, would Queen Elizabeth identify herself as a vulnerable person automatically because she happens to be in the older age group?

In contrast, Spiers (2000) also identified the emic perspective which relates to the ‘state of being threatened and a feeling of fear of harm’. This perspective is identified by the individual actually experiencing feeling vulnerable; therefore, it is an individual interpretation of the experience. In this perspective, vulnerability is exactly what the person experiencing it says it is; therefore, if they say they are experiencing feeling vulnerable, then they are. Under this perspective, any individual can experience feeling vulnerable regardless of age, gender, ability, etc. This way of seeing vulnerability is more silent within the professional literature. For example, have you ever considered that every client you have worked with could have experienced feeling vulnerable, and indeed you yourself could also experience feeling vulnerable (please refer back to the notes you made previously, in Box 2.1)

To date, in this chapter we have examined some definitions of vulnerability and established the link between vulnerability, health, and healthcare. What we need to do now is to further explore the different theoretical explanations of vulnerability, so that we can appreciate the complexity of this phenomenon and be better placed to understand why some individuals (including ourselves) may experience feeling vulnerable.

As we have acknowledged, an individual experience of vulnerability can occur for many different reasons and we need to understand these in order to:

There are different theoretical explanations of vulnerability (Box 2.6).

Each of these different explanations will now be considered in turn identifying the implications for professional practice.

The predominant perspective of vulnerability in healthcare identifies vulnerable populations, as ‘social groups who have an increased relative risk or susceptibility to adverse health outcomes … as evidenced by morbidity and premature mortality’ (Flaskerud and Winslow 1998: 69). At the centre of this perspective is the notion of risk and harm; indeed, almost all uses of the term vulnerable in healthcare reflects epidemiological principles of population-based relative risk. As such this reflects the etic, normative perspective of vulnerability. Vulnerable groups therefore include people who are judged to be ‘old’ (Spiers 2000, Rydeman and Törnkvist 2006), ‘poor’ (Spiers 2000, Furumoto-Dawson et al. 2007), children (Hewitt-Taylor and Heaslip 2012, Clark 2007, Furumoto-Dawson et al. 2007), ‘mentally ill’ (Spiers 2000), and ‘ethnic minorities’ (Pitkin Derose et al. 2007). A key drive in this perspective is that vulnerability is seen as a problem to be solved which then drives statutory guidance and public health action.

So let us take the example of older people, who are often identified as a vulnerable group due to increased morbidity and mortality (Spiers 2000, Rydeman and Törnkvist 2006). We know that there is an association between aging and ones increased propensity to fall, and that when older people fall there is an increased likelihood of them sustaining an injury as well as a potential that they may die as a result of the fall (NICE 2004). This knowledge of their increased vulnerability to falling has led to a variety of practice initiatives geared at reducing the likelihood that people will fall. As such, there has been national guidance such as the National Service Framework for Older People (DoH 2000a) and Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and prevention of falls (DoH 2000a, NICE 2004) as well as the development of falls clinics in order to standardise and enhance the clinical care of older people who either fall or are at risk of falling. However, it must be remembered that not all older people fall. In addition, focusing upon vulnerability in this manner does not inform us of the lived experience of vulnerability in older age. Indeed, it can be argued that many older people may not define themselves as vulnerable and therefore what right do we as practitioners have to tell them they are.