Contents

Preface to First Edition

Preface to Second Edition

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 General Considerations and Anaesthesia

1.1 Instrumentation

1.2 Asepsis

1.3 Sutures and suturing

1.4 Pre-operative assessment

1.5 Restraint

1.6 Premedication and sedation

1.7 Local analgesic drugs

1.8 Regional analgesia

1.9 General anaesthesia

1.10 Shock

1.11 Fluid therapy

1.12 Anti-microbial chemotherapy

1.13 Wound treatment

1.14 Cryotherapy

1.15 Coccygeal venepuncture

1.16 Hereditary defects

CHAPTER 2 Head and Neck Surgery

2.1 Disbudding and dehorning

2.2 Trephination of frontal sinus (for empyema)

2.3 Entropion

2.4 Third eyelid flap

2.5 Neoplasia of eyelids

2.6 Ocular foreign body

2.7 Enucleation of eyeball

2.8 Tracheotomy

2.9 Oesophageal obstruction

CHAPTER 3 Abdominal Surgery

3.1 Topography

3.2 Exploratory laparotomy, left flank

3.3 Exploratory laparotomy, right flank

3.4 Rumenotomy

3.5 Temporary rumen fistulation

3.6 Left displacement of abomasum

3.7 Right dilatation, displacement and torsion (volvulus) of abomasum

3.8 Other abomasal conditions

3.9 Caecal dilatation and dislocation

3.10 Intestinal intussusception

3.11 Other forms of intestinal obstruction

3.12 Peritonitis

3.13 Umbilical hernia and abscess

3.14 Alimentary conditions involving neoplasia

3.15 Vagal indigestion (Hoflund syndrome)

3.16 Abdominocentesis

3.17 Liver biopsy

3.18 Anal and rectal atresia

3.19 Rectal prolapse

CHAPTER 4 Female Urinogenital Surgery

4.1 Caesarean section (hysterotomy)

4.2 Vaginal and cervical prolapse

4.3 Uterine prolapse

4.4 Perineal laceration

4.5 Ovariectomy

CHAPTER 5 Teat Surgery

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Stenosis of teat orifice, streak canal or Furstenberg’s rosette

5.3 Teat lumen granuloma

5.4 Teat base membrane obstruction

5.5 Traumatic lacerations of teat

5.6 Imperforate teat

5.7 Incompetent teat sphincter

5.8 Teat amputation

5.9 Discussion

CHAPTER 6 Male Urinogenital Surgery

6.1 Preputial prolapse

6.2 Penile haematoma

6.3 Urolithiasis

6.4 Prevention of intromission

6.5 Vasectomy

6.6 Epididymectomy

6.7 Congenital penile abnormalities

6.8 Penile neoplasia

6.9 Castration

CHAPTER 7 Lameness

7.1 Incidence

7.2 Economic importance

7.3 Terminology

7.4 Interdigital necrobacillosis

7.5 Interdigital skin hyperplasia

7.6 Solear (solar) ulceration

7.7 Punctured sole

7.8 White line separation and abscessation

7.9 Laminitis (coriosis)

7.10 Other digital conditions

7.11 Deep digital sepsis

7.12 Digital amputation

7.13 Other digital surgery

7.14 Hoof deformities, overgrowth and corrective foot trimming

7.15 Footbaths

7.16 Check lists for herd problems

7.17 Infectious arthritis (‘joint ill’) in calves

7.18 Contracted flexor tendons

7.19 Tarsal and carpal hygroma

7.20 Patellar luxation

7.21 Spastic paresis

7.22 Hip luxation

7.23 Stifle lameness

7.24 Nerve paralysis of limbs

7.25 Limb fractures

7.26 Use of acrylics and resins in orthopaedic problems

7.27 Antibiotherapy of bone and joint infections

Appendices

1 Further Reading

2 Abbreviations

3 Useful addresses

4 Conversion factors for old and SI units

Index

© 2005 David Weaver, Adrian Steiner and Guy St Jean

Editorial Offices:

Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1865 776868

Blackwell Publishing Professional, 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA

Tel: +1 515 292 0140

Blackwell Publishing Asia, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

Tel: +61 (0)3 8359 1011

The right of the Authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published as Bovine Surgery and Lameness in 1986 by Blackwell Scientific Publications

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weaver, A. David (Anthony David)

Bovine surgery and lameness / A. David Weaver, Guy St. Jean, Adrian Steiner. – 2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-10: 1-4051-2382-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-2382-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Cattle–Surgery. 2. Lameness in cattle. I. St. Jean, Guy. II. Steiner, Adrian, 1959– III. Title.

SF961.W43 2005

636.089′7–dc22

2004028333

ISBN 10: 1-4051-2382-6

ISBN 13: 978-14051-2382-2

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website:

www.blackwellpublishing.com

Preface to First Edition

This book aims to give the nuts and bolts of practical bovine surgery and lameness.

The text is directed to veterinary students in the clinical years of their undergraduate courses, and to recent and older veterinarians, who experience a limited amount of cattle surgical material. In the interests of compression and simplicity, a single procedure is described in some detail, while the alternatives, known to be equally good in the hands of others, are briefly listed. No apology is made for such dogmatism.

The text includes frequent reference to specific types and sizes of instruments and suture materials. In view of the current move to the metric system, albeit late in the Anglo-American world, all figures are metric, but a comparative scale is included.

All surgery presents a series of challenges, and this accounts for the popularity of the discipline in both the veterinary and medical professions. The challenges in bovine surgery differ from those met by the companion animal surgeon. The first is the economic question: is surgery economically justified? The balance of a judgement to perform a caesarean section on a heifer with dystocia rather than to salvage the animal may be a fine one. This is rarely so in the companion animal field. Humane considerations often complicate an otherwise simple problem.

Other challenges include the anatomical knowledge pertinent to the procedure, the method of restraint and analgesia or anaesthesia, the demands of manual dexterity, and the physical stress imposed on patient and surgeon alike, when surgery must be performed in a sub-optimal environment, which may be the corner of a field or a dark spot in a dusty cowshed.

The inevitable lack of experience in bovine surgery of a young veterinary graduate may persist as a result of a certain apathy among colleagues in the practice group. This apathy is reflected in the difficulties of maintaining equipment necessary for emergency surgery, and results in impatience at the overall time required to complete a bovine operation. The axiom ‘time is money’ applies as much to the bovine surgeon as to anyone and, since proper instrumentation, asepsis, effective anaesthesia and basic techniques are the keystones to effective craftsmanship, these points are discussed in the first section.

Succeeding chapters logically pass from the head and neck to the abdomen, thence to the female urinogenital system and teat surgery, the male urinogenital apparatus, and finally to lameness. No attempt can be made to treat a subject in depth. The further reading list is similarly selected purely as a basic literature guide.

The reader will often have to consider ethical implications of proposed prophylactic or curative surgery. Animal welfare considerations are becoming increasingly important in many countries. Is castration justified? Is it justified in older cattle, either on humane, economic or management grounds? The relevant veterinary literature is sparse and the conclusions are conflicting. Responsibility rests with the veterinarian.

Why does a farm experience an ‘epidemic’ of left abomasal displacement cases? The veterinarian may search for further advice on prophylaxis. Such an investigation will often involve other disciplines. A multi-disciplinary approach is particularly needed in herd lameness problems, and the check lists (see pp. 236–238) should stimulate objective recording of herd data and take the emphasis away from repetitive back-breaking treatment of the individual cow.

Serving as a prophylactic, diagnostic and therapeutic instrument, bovine surgery therefore fits into the concept of a herd health programme.

A. David Weaver

Columbia, September 1985

Preface to Second Edition

After an interval of nearly 20 years it seemed appropriate to consider an update. The first edition, translated into 6 languages, appeared to fulfil a need, and a minisurvey of UK veterinarians graduated 2–40 years ago showed unanimous support for such a revision, all emphasising the need for a compact text (‘not too many words on a page’, ‘ more simple illustrations’) of the standard surgical techniques used in cattle on the farm.

The publishers welcomed the suggestion that two outstanding bovine surgeons, from Switzerland and North America, be invited to add their personal expertise and to provide a wider perspective. As a result this edition has been considerably expanded and has many more line drawings. The style and format have remained strictly instructional, sometimes even dogmatic. Only rarely are alternative techniques discussed, a notable exception being abomasal surgery.

We consider this book should help students in their clinical training, especially when experiencing farm animal practice for the first time, as well as new graduates, inevitably inexperienced, and those veterinarians in mixed practice who may only occasionally be called out for bovine surgical interventions.

More emphasis is placed on animal welfare, for example in suggestions for peri-operative analgesia and anti-inflammatory medication. The authors are all too well aware of the problematic national (EU, other European and North American) regulations on permissible drug usage, and also appreciate that each veterinarian has his or her own preferences.

Effective local, regional or occasional general anaesthesia is demanded today for all painful interventions in cattle. The general public, and not only the involved dairy or beef farmer, also demands that more attention be paid to food safety, and to the replacement of costly therapeutic drugs (often unavailable in developing countries) by prophylactic antimicrobials, and preferably zero drug usage. Such demands necessitate an enhanced need for good antisepsis and sterility.

Surgery may only be carried out when the condition of the patient permits it. The correct decision may be difficult, for example in right-sided abomasal disease, severe dystocia and digital surgery. Economical considerations and farm facilities must also be evaluated in each potential case.

The ever increasing risk over the last 20 years of litigation involving the veterinarian has resulted in more emphasis on the avoidance of potential disasters such as accidental injury to the animal or attendants, or unexpected sequelae to standard surgical procedures. The farm manager or attendant should always be informed beforehand of possible problems, and, we believe, could well occasionally be shown relevant sections of our text on the farm. No veterinarian should undertake any intervention when lacking the necessary confidence or knowledge. We believe bovine surgeons must understand their important role in the worldwide cattle industry today.

The authors trust that this pocketbook will again provide a handy vademecum and a valuable and practical tool in daily practice.

A. David Weaver, Guy St. Jean, Adrian Steiner

February 2005

Acknowledgements

Permission again to reproduce illustrations from the first edition was graciously given by several authors and publishers (Dyce, Pavaux, Cox, Smart), while new illustrations came from several sources as below.

Figs. 1.7, 2.5, 3.2, 3.22 Dr. K.M. Dyce, Edinburgh and W.B. Saunders ‘Essentials of Bovine Anatomy’, 1971 by Dyce and Wensing

Figs. 2.4, 2.9, 3.1, 3.4, 3.5 Professor Claude Pavaux, Toulouse, and Maloine s.a. editeur from ‘Colour Atlas of Bovine Anatomy: Splanchnology’ 1982

Fig. 3.15, Dr. John Cox, Liverpool, and Liverpool University Press ‘Surgery of the Reproductive Tract in Large Animals’ 1981

Fig. 3.24, Dr. M.E. Smart, Saskatoon and Veterinary Learning Systems, Yardley, PA, USA from ‘Compendium of Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian’ 7, S327, 1985

Fig. 3.17, Dr. H. Kümper, Giessen and Blackwell Science from ‘Innere Medizin und Chirurgie des Rindes’ 4e 2002 edited by G. Dirksen, H-D. Gründer and M. Stöber fig. 6.125)

Fig. 4.6, Dr. R.S. Youngquist, Columbia, Missouri and W.B. Saunders from ‘Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology’ 1997 (fig. 57.2)

Fig. 7.12, Dr. M. Steenhaut, Gent, and Blackwell Science from ‘Innere Medizin und Chirurgie des Rindes’ 4e 2002 edited by G. Dirkson, H-D. Gründer and M. Stöber (fig. 9.159)

Jan Huckin, Newbury, produced many new illustrations from rough sketches by the first author, as did also Don Connor in Missouri. Many others come from the hand of Eva Steiner. John Sprout, Castle Douglas, not only commented usefully on the entire manuscript but also supplied some excellent sketches (Figs. 1.14, 1.15 and 2.2)

Several practising veterinarians have given useful advice including Keith Cutler (Immobilon), Simon Bouisset of Toulouse (analgesics and antiinflammatories), Bob Miller of Columbia, Missouri, Rupert Hibberd, David Noakes, David Ramsay, and Jan Downer. David Pritchard (DEFRA) and Vincent Molony (Edinburgh) advised on certain aspects of animal welfare legislation pertinent to the UK situation. The RCVS Library helped with some literature sources, and David Taylor checked on the ever-changing microbiological nomenclature, while Lesley Johnson (Veterinary Medicines Directorate) commented on several contentious tables in chapter 1. Appendix 4 was critically assessed for accuracy by Maureen Aitken, Newbury.

The entire manuscript was typed by Christina McLachlan of Milngavie, who deserves thanks for both her accuracy and patience.

Finally thanks are given to all at Blackwell Publishing for their cooperation and advice, including Susanna Baxter, Samantha Jackson, Sophia Joyce, Emma Lonie, Sally Rawlings and Antonia Seymour, also to their copy-editor Liz Ferretti.

Guy St. Jean thanks his mentors Bruce Hull, Michael Rings and Glen Hoffsis, not only for their earlier advice and encouragement during his residency, but also for their continuing friendship. He also thanks Kim Carey for secretarial help and his wife Kathleen Yvorchuk-St. Jean for continual support. Adrian Steiner would like to dedicate the book to Christian.

A. David Weaver, Guy St. Jean and Adrian Steiner, April 2005

The authors have made every effort to ensure that drugs, their dosage regimes and withdrawal periods are accurate at the time of publication. Nevertheless, readers should check the product information provided by the manufacturer of each drug before its use or prescription.

Drug authorisation by regulatory authorities varies from country to country, and drug withdrawal times, dependent on maximum residue limits (MRL), which are derived from residue depletion studies, can also vary from a parent (proprietary) product to a generic equivalent. Withdrawal times vary within member states of the EU, North America and elsewhere in the world (shown in Table 1.15).

The reader should exercise individual judgement in coming to a clinical decision on drug usage, bearing in mind professional skill and experience, and should at all times remain within the regulatory framework of the country.

Instruments should be maintained in good condition and, for common procedures, in sterile surgical packs (caesarean section, laparotomy, teat surgery, orthopedic surgery).

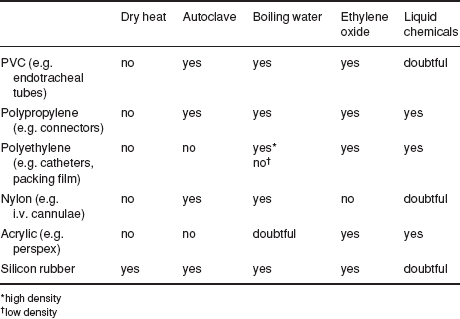

Instruments should preferably be sterilised by one of the first two methods listed below:

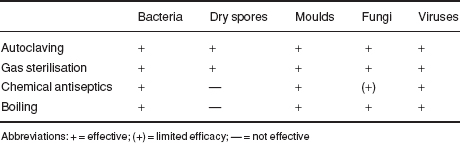

Table 1.1 Suitability of various surgical materials for sterilisation.

Table 1.2 Efficiency of different methods of sterilisation.

The following is a suggested list of equipment to cover most eventualities.

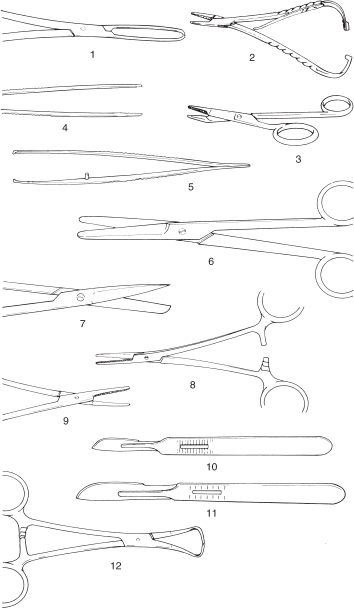

Figure 1.1 Basic instruments for caesarean section or laparotomy.

1. Allis tissue forceps; 2. McPhail’s needle holder; 3. Gillies combined scissors and needle holder; 4. plain forceps; 5. rat tooth forceps; 6. Mayo scissors (blunt/blunt), slightly curved; 7. Mayo scissors (pointed/blunt), straight; 8. straight haemostatic forceps; 9. curved haemostatic forceps; 10. scalpel handle no. 4 and no. 22 blade; 11. scalpel handle no. 3 and no. 10 blade; 12. towel clip (Backhaus).

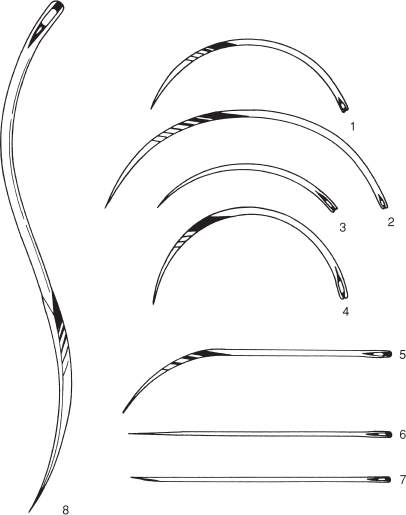

Figure 1.2 Suture needles (shown full scale).

1. and 2. 3/8 circle cutting-edged 4.7 and 7 cm; 3. 3/8 circle round-bodied (taper cut) 4.5 cm; 4. 1/2 circle cutting-edged 4.6 cm; 5. 1/2 curved cutting-edged 6.7 cm; 6. intestinal straight round-bodied (Mayo) 6.3 cm; 7. straight cutting-edged (Hagedorn) 6.3 cm; 8. double-curved postmortem needle 12.5 cm.

Also needed are suture needles, which should include two each of the following types and sizes (see Figure 1.2):

Bovine surgery involving regions where adequate skin preparation is feasible (i.e. with avoidable microbial contamination of tissues or sterile materials) should be performed under aseptic conditions. Instruments and cloths should be sterile.

Preparation of operative field (e.g. flank):

Hands are kept in contact with the disinfectant for at least five minutes. Effective hand sterilisation procedures include:

Table 1.3 Properties of three common antiseptic compounds.

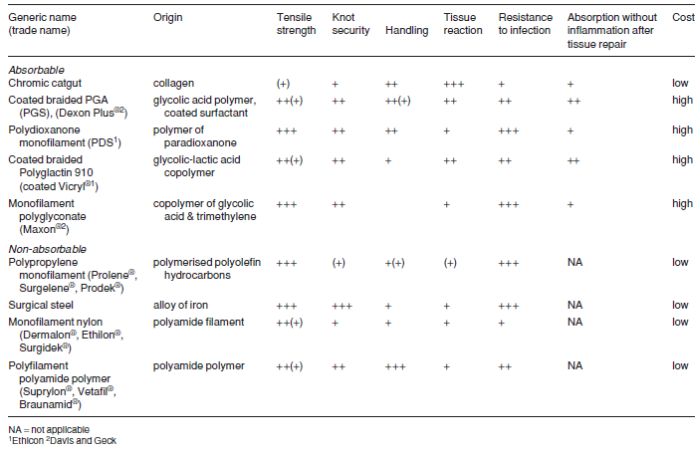

Few topics produce such outspoken opinions and dogma as the ‘best’ suture material and pattern for specific surgical procedures in domestic animals, including cattle. Suture materials are constantly being improved and new products come onto the veterinary market at regular intervals (see Tables 1.4 (a) and (b) and 1.5). This section selects a limited number of materials and methods of usage, and attempts to justify the selection. In few cases can the cost of the material be considered an important factor in selection.

Table 1.4(a) Equivalent gauges for suture materials (metric gauge in this text).

| Metric (also Ph. Eur. = European Pharmacopoe) | BP | USP |

| 1 | 5/0 | 5–0 (6–0) |

| 1.5 | 4/0 | 4–0 (5–0) |

| 2 | 3/0 | 3–0 (4–0) |

| 2.5 | 2/0 | — |

| 3 | 0 (3/0) | 2–0 (3–0) |

| 3.5 | –(2.0) | 0 (2–0) |

| 4 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| 5 | 2 or 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| 6 | 3 or 4 (2) | 3 & 4 (2) |

| 7 | 5 (3) | 5 (3) |

| 8 | 6 (4) | 6 (4) |

| 9 | 7 (5) | 7 (–) |

| 10 | 8 (6) | 8 (–) |

| 11 | 9 (7) | 9 (–) |

| 12 | 10 (8) | 10 (–) |

Values for absorbable suture materials (e.g. multifilament polyglactin 910 [Vicryl] catgut and collagen) are given in brackets

Multifilament polyglycolic acid or PGA Dexon, is also classified as non-absorbable in the above table

BP = British Pharmacopoeia USP = United States Pharmacopoeia

Table 1.4(b) Equivalent gauges for hypodermic needles (metric gauge in this text).

| Metric mm external diameter |

BWG/G UK/North America |

| 2.10 | 14 |

| 1.80 | 15 |

| 1.65 | 16 |

| 1.45 | 17 |

| 1.25 | 18 |

| 1.10 | 19 |

| 0.90 | 20 |

| 0.80 | 21 |

Metric internal diameter is 0.05–0.1 mm less than the external diameter above

Non-absorbable suture materials:

Absorbable suture materials:

Selection of suture material should be based on the known biological and physical properties of the suture, wound environment and tissue response to the suture.

Monofilament nylon remains encapsulated in body tissues when buried, but the inflammatory reaction is minimal. It has great size-to-strength ratio and tensile strength. It is somewhat stiff and is therefore not particularly easily handled, an important point when operating in sub-optimal conditions of poor light and awkward corners, where the surgeon is bent down. Knot security is only fair.

Multifilament polyamide polymer, encased in an outer tubular sheath (pseudomonofilament), has good strength and provokes little tissue reaction unless the outer sheath is broken, but it loses strength when autoclaved. It is therefore usually drawn from a sterile spool as and when required. It is very easily handled.

Surgical steel has the greatest tensile strength of all sutures, and retains strength when implanted. It has the greatest knot security and creates little or no inflammatory reaction. Surgical steel however tends to cut tissue, has poor handling and cannot withstand repeated bending without breaking. It is sometimes used in tissues that heal slowly (e.g. infected linea alba).

Of the six absorbable materials listed, chromic catgut is still commonly used, but has been replaced by synthetic absorbable material in cattle practice. Catgut has relatively good handling characteristics, but also the disadvantages of relatively rapid loss of strength in well vascularised sites (50% in the first week) and poor knot security (tendency to unwrap and loosen when wet). The potential minute risk of the transfer of infectious prion material into food-producing animals (e.g. cattle) and thence into the human food chain has led to a ban on the use of chromic catgut in some countries (vCJD risk).

Table 1.5 Comparative qualities (graded undesirable to desirable, + to +++), of nine selected suture materials for cattle.

Multifilament polyglycolic acid (PGA) has greater strength which is lost evenly, provoking much less tissue reaction than chromic catgut. PGA is non-antigenic, has a low coefficient of friction and therefore requires multiple throws to improve knot security, but is easily handled.

Monofilament polydioxanone (PDS) is very strong, retaining its strength for many weeks (58% at four weeks), is easily handled, has good knot security, and has the sole disadvantage of provoking an initial tissue reaction which recedes during suture absorption.

‘Soft’ catgut is undoubtedly the most easily handled absorbable material for delicate bowel anastomoses, its quality even exceeding that of PGA, but it is not yet widely available. Plain or soft catgut is absorbed quickly and maintains its strength for a short time. In coming years PDS and PGA are likely to slowly replace chromic catgut, which will retain its place as a general purpose material. Vicryl® in its coated form is very easy to handle, has minimal tissue reaction and tissue drag. It is stable in contaminated wounds. Polyglyconate monofilament (Maxon™) has three times the strength of Vicryl® at day 21 of wound healing.

Suturing can only be performed efficiently with needles which are rust-free, sharp, and strong enough for insertion through the specific tissue. A selection of needles may be conveniently maintained on a rack in a metallic sterile container.

Suture patterns are discussed under the specific procedures. Skin under considerable or potential tension at certain sites, such as the vulval lips and peri-anal region (e.g. following replacement of prolapsed uterus, vagina or rectum), is usually sutured with sterile woven nylon tape 3–5 mm diameter.

Assessment should include numerous factors apart from the physical condition of the subject:

General physical examination is essential before emergency or elective surgery.

Under farm practice conditions laboratory tests may not be performed, but the major parameters very simply estimated with minimal apparatus are:

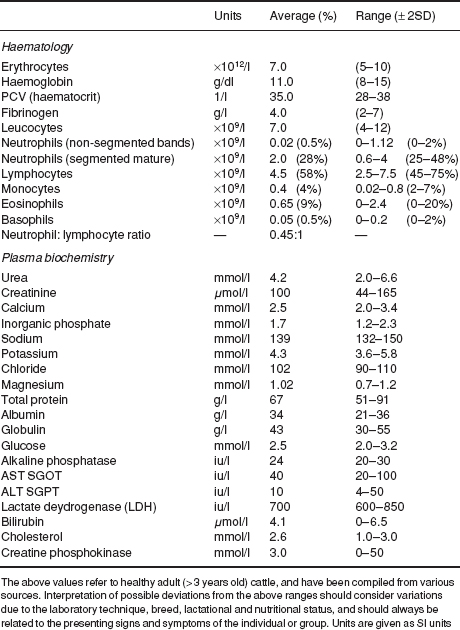

Normal haematological and biochemical parameters of cattle are listed in Table 1.6.

In some abdominal conditions (abomasal torsion or volvulus, intestinal obstruction) estimation of plasma electrolytes (e.g. chloride) is valuable in assessing prognosis and calculating requirements for fluid replacement.

Fluid therapy is discussed in Section 1.11, p. 42.

Restraint is necessary for:

Restraint may involve physical manipulation of tail, head or nares, or involve application of halter and ropes.

Physical restraint by stockman includes:

Rope restraint includes:

Many forms of cattle crush or squeeze chute are available with excellent head restraint, which are suitable for surgery of the head and cranial neck (e.g. tracheotomy) and of the perineum. (An essential feature of these crushes or chutes is the ability to release the head rapidly should the animal collapse.) Many are unsuitable for flank laparotomy, caesarean sections or rumenotomy, however manufacturers will modify sides of crushes (lowering horizontal bar and with a greater space between vertical bars) to improve access to the paralumbar fossa. A veterinary practice may find it advantageous to have such a crush available for surgery on the practice premises or to be transported to the farm. Many crushes have poor facilities for the elevation and restraint of hind- or forelimbs for clinical examination and digital surgery. An exception is the Wopa crush, which is excellent for teat and feet surgery. Suitable crushes may easily be made on the farm and tilted either by manual means or by power.

Table 1.6 Reference ranges (haematology and plasma biochemistry) in cattle.

The use of a crush/squeeze chute should never replace adequate analgesia for surgical procedures.

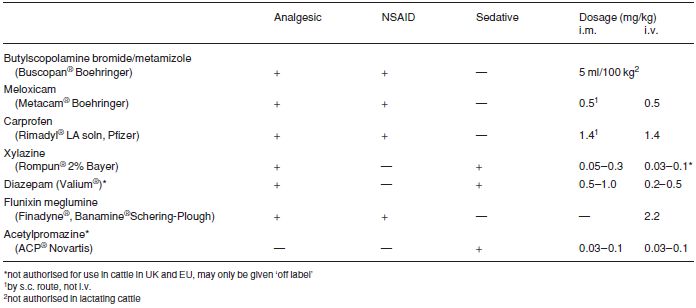

Premedication and sedation (see Table 1.7) have five aims:

Very few anaesthetic drugs are approved for use in farm animals. Those known to the authors include azaperone, lidocaine, methoxyflurane and thiamylal (USA). Xylazine is approved for use in cattle in Canada and the UK, and acepromazine is also approved for use in cattle in Canada.

Although not approved for use in cattle in many countries (including the USA), several analgesic drugs (e.g. flunixin meglumine, dipyrone 50% and phenylbutazone, in addition to xylazine) are beneficial as adjunct therapy both pre- and post-operatively in cattle with obvious somatic pain and discomfort. Pre-operative use of analgesics reduces the degree of operative discomfort and post-operative pain. For any medication for cattle in the USA it is the veterinarian’s responsibility to consult the Animal Medical Drug Use Clarification Act for guidelines for the extralabel use of drugs, and the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Databank (FARAD) for withdrawal times. (See Appendix 3, pp. 267, legal and professional bodies, for contact details of FARAD).

Very useful analgesic and sedative. Xylazine also causes muscle relaxation.

Causes ruminal stasis, increases salivation, and effects of higher dose rate are somewhat unpredictable as animal may or may not become recumbent. Xylazine is unsuitable as the sole agent for minor surgery when more than a single painful stimulus is anticipated (e.g. unsuitable as method of analgesia in teat surgery; lancing and drainage of large flank abscess is suitable indication). Xylazine is contra-indicated in the last trimester of pregnancy due to its stimulation of uterine smooth muscle (risk of abortion). It may be used if a uterine relaxant is given before xylazine. Xylazine is contra-indicated in extreme heat, as hyperthermia may result. Avoid accidental intra-carotid injection! Violent seizures and possibly temporary collapse are likely.

Table 1.7 Activity and dosage of selected analgesic, anti-inflammatory and sedative drugs in cattle.

For anaesthetic premedication 0.1 mg/kg xylazine i.m., 0.2 mg/kg i.m. for minor procedures in combination with local analgesia. A faster and more predictable effect is seen following i.v. use (not authorised) at 0.1 mg/kg.

Xylazine sedation, analgesia, cardiopulmonary depression and muscle relaxation are reversible. Also xylazine overdosage (e.g. by inadvertent use of the equine preparation) may be antagonised by different drugs including:

Doxapram acts by direct action on aortic and carotid chemoreceptors and medullary respiratory centre, while yohimbine antagonises xylazine sedation by blocking central α2-adrenergic receptors.

Long established sedative is given orally (30–60 g as 5% solution but bull requires 120–160 g) or i.v. (5–6 g/50 kg bodyweight as 5% solution). The solution is irritant, and perivascular injection is likely to lead to necrosis and severe skin slough. Infusion (total volume about 1 litre for adult cow) should be made slowly via i.v. catheter over a minimal 5 minute period, since narcosis continues to deepen after completion of injection. Chloral hydrate is not an analgesic. Concentrations required to produce general anaesthesia cause severe, possibly fatal respiratory and circulatory depression.

Drug reduces quantity and increases viscosity of saliva. Premedicant dose in adult cow is 60 mg s.c.

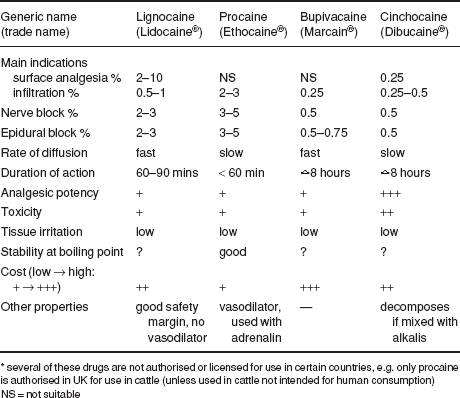

Table 1.8 Properties of four local analgesic drugs (all hydrochloride salts).*

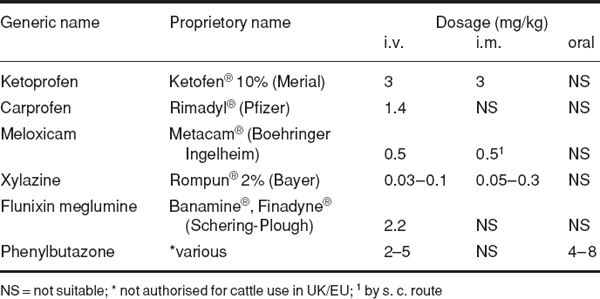

The four drugs of greatest value today are the hydrochloride salts of lignocaine, procaine, bupivacaine and cinchocaine (see Tables 1.8 and 1.9).

Lignocaine (Lidocaine/USP) has largely replaced procaine as it has the advantage of:

It is however no longer authorised for cattle in the UK and EU states, as it has no MRL.

Proprietary names include Lignodrin 2% (Vétoquinol), Lignol (Arnolds), Locaine 2%, (Animalcare), Locovetic (Bimeda).

Toxic effects are rarely encountered (e.g. inadvertent intravascular injection); they include drowsiness, muscle tremors and respiratory depression, convulsions and hypotension. Toxicity depends on the venous concentration, which in turn depends largely on the rate of absorption. Concentrations for cattle are 2–3%, although 1% is probably adequate for infiltration, nerve block and epidural analgesia.

Table 1.9 Selected analgesics for cattle.

Proprietary products often contain adrenaline (epinephrine) (concentration 1:200 000). Adrenaline prolongs the activity of lignocaine and reduces the possibility of toxic side-effects.

Lignocaine is also available as:

Procaine (novocaine) largely replaced cocaine, and has in turn been displaced by lignocaine. However procaine may have economic advantages over lignocaine. Proprietary brands include Planocaine®, Novutox® and Willcain®.

Combined with adrenaline hydrochloride, procaine absorption is slow, solutions may be sterilised by boiling and there is minimal tissue irritation. Metabolite para-amino benzoic acid inhibits action of sulphonamides.

Bupivacaine, marketed as Marcain® (Astra) with and without adrenaline (1:4 000 000) as a 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75% (plain) solution, has the following properties:

It costs considerably more than lignocaine. The product will doubtless find more widespread use.

Cinchocaine (Nupercaine™, Dibucaine®) is more toxic than procaine, but concentrations for epidural block and surface analgesia are lower (0.5%). Other properties include:

Carbocaine®-V or Mepivacain (Pharmacia and Upjohn), 2% solution is sometimes used for infiltration and epidural block, is equivalent to lignocaine and has several hours duration of activity.

Regional analgesia is the preferred method of anaesthesia for many surgical procedures in cattle. Its advantages over general anaesthesia (GA) (see Section 1.9, p. 36) include:

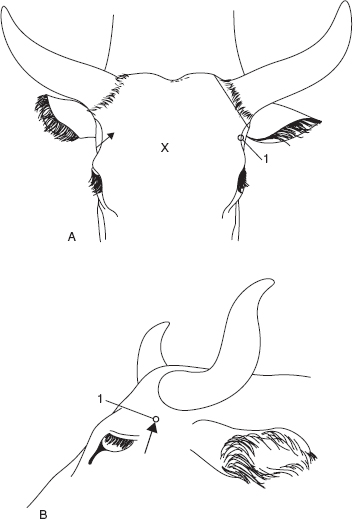

Sensitive horn corium is largely innervated by the cornual branch of the zygomatico-temporal division of the maxillary nerve (from cranial V). Caudally a few twigs of the first cervical nerve make a variable contribution to innervation. The cornual nerve leaves the lacrimal nerve within the orbit, passes through the temporal fossa and around the lateral edge of the frontal bone, covered by fascia and thin frontalis muscle. The nerve is blocked a little below the lateral ridge of the frontal crest, about halfway between the lateral canthus of the eye and the horn (bud) base. The cornual artery and vein are close to the site of block.

Figure 1.3 Site for cornual nerve block. A. rostral view; B. lateral view; 1 cornual branch of zygomatico-temporal nerve. Note angle of insertion of needle, and also line of cut in skin at horn base in dehorning (see Section 2.1, p. 57). X site on skull for captive bolt euthanasia.

Disposable syringe, 10 ml for adults, 5 ml for calves, 2.4 cm 20 gauge hypodermic needle, 2% plain lignocaine or 5% procaine solution (2–8 ml depending on size).

Failures are due to:

Exotic breeds sometimes have an additional nerve supply from the infratrochlear nerve to the medial aspect of the horns (similar to that seen in goats). It is blocked by subcutaneous infiltration across the forehead, transversely and level with the site of the cornual block.

Surgery of upper eyelid, trephination of frontal sinus.

Alternative technique for regional anaesthesia is local infiltration.

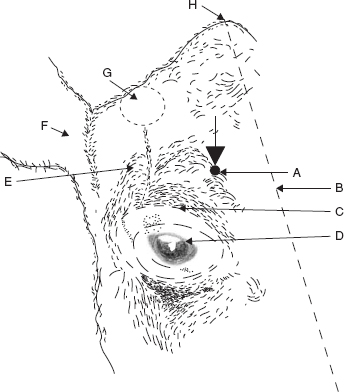

Innervation of ocular structures is complex:

Figure 1.4 Supra-orbital nerve block. Oblique diagrammatic view of right side of head. Foramen is palpable about 3 cm dorsal to upper bony margin of orbit. Long dotted line is midline; dotted line is horn base. A. supra-orbital foramen; B. median line; C. margin of bony orbit; D. orbit; E. frontal bone; F. right ear; G. horn base; H. poll.

The oculomotor, trochlear, ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal and abducens nerve emerge from the foramen rotundum orbitale.

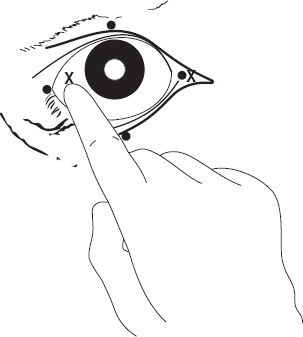

Figure 1.5 Retrobulbar block. Two methods are shown:

(a) needle insertion at four points (black circles) through conjunctiva under careful digital guidance (4 × 8–10 ml);

(b) needle insertion at lateral or medial (×) canthus, again perforating conjunctiva to deposit solution at orbital apex (20–30 ml).

Use 18 gauge needle 15 cm long with marked curvature, advancing tip slowly.

Another technique of retrobulbar injection involves placement at four sites (medial, lateral, dorsal and ventral canthi) through the conjunctiva of 10 ml solution at each site, followed by infiltration of the eyelid margins (see Figure 2.8).

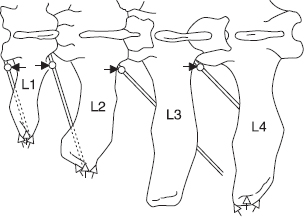

Laparotomy, omentopexy, rumenotomy, caesarean section (flank incision); ruptured bladder in calves (midline incision: bilateral paravertebral).

Disposable 20 ml syringe, 3 × 1.25 metric 10 cm needles, such as Howard Jones type without stilette, 2% lignocaine with adrenalin. Total volume of solution is 60 ml (three sites) or 80 ml (four sites).

Fat beef cattle may require needle length up to 12–15 cm to reach correct depth.

Figure 1.6 Paravertebral anaesthesia: horizontal diagrammatic view of left lumbar vertebrae 1–4 to show course of last thoracic (T13), first three lumbar nerves, and position of needle. Black arrows indicate the direction in which the vertical needle point is ‘walked off’ the transverse process in the proximal technique. White arrows show the area of infiltration above and below the tips of processes 1, 2 and 4 in the distal technique.

Commencing analgesia is noted by convex curvature of spine (scoliosis) on injection side resulting from relaxation of longissimus dorsi and flank musculature. Analgesia is complete within 10–15 minutes.

Field of analgesia runs slightly obliquely ventrally and caudally to midline. Innervation of the individual dermatomes overlaps so that a block of single nerve produces a very narrow (1–4 cm wide) analgesic skin band over the flank. T13 innervates skin over middle of last 1–2 ribs (12–13), while L3 block causes analgesia as far caudal as os coxae. Dorsal ramus innervates skin over upper one third of flank skin, the ventral ramus the remainder of the flank (see Figure 1.7).

Variations of technique have included production of insensitive skin wheal prior to insertion of a longer needle, and insertion of a stout 2.1 mm diameter needle to infiltrate the musculature, later replaced by a finer and longer needle.

Figure 1.7