Dr. Christina Fritz

A Journey through

the Horse’s Body

I would like to thank Lars and Lennard Wittenburg for their patience and support in the creation of this manuscript during the family holiday.

Imprint:

Copyright ©2012 Cadmos Publishing Limited, Richmond, UK

Copyright of original edition © 2011 Cadmos Verlag GmbH, Schwarzenbek, Germany

Design: Ravenstein, Verden

Setting: Das Agenturhaus, Munich

Translation: Helen McKinnon

Editorial of the original: Maren Müller

Editorial of this edition: Christopher Long

Cover image: Edition Boiselle/Susanne Retsch-Amschler

Photographs in book: Cadmos archive, Dr. Christina Fritz, Kai Kreling,

Dr. Richard Maurer, Christiane Slawik

Illustrations in book: Juliane Denmann, Maria Mähler, Susanne Retsch-Amschler

Printed by: Grafisches Centrum Cuno, Calbe

E-Book conversion: Satzweiss.com Print Web Software GmbH

All rights reserved: No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Printed in Germany

ISBN 978-0-85788-006-2

eISBN 978-0-85788-724-5 (EPUB)

eISBN 978-0-85788-725-2 (MOBI)

www.cadmos.co.uk

Dear Reader,

Welcome to a voyage of discovery through the horse’s body. In this book, I will describe to you the structure and function of all of the parts of the horse’s body. The book features extensive image material to help clarify the theoretical explanations. By understanding anatomy, you will be able to ride your horse better and keep him in an environment that suits him best.

Look at your horse in a whole new light. See him not just as your friend and partner, but as the steppe animal, the herd animal, the flight animal that has evolved over millennia to become better and better adapted to his environment. Above all, the horse is an animal of movement that, in the wild, would be active for up to 16 hours a day in search of food. This is only possible with a specially adapted musculoskeletal system, to which a particularly detailed chapter of this book has been dedicated. The cardiovascular system and the respiratory system are also adapted to this life in motion. The horse’s digestive system is perfectly suited to the diet of a steppe animal and is fundamentally different from that of the carnivorous dog or omnivorous human. I will also go into these special features in greater depth in this book.

Embark on a journey through the horse’s body and you will never look at your horse in the same way again!

People have been interested in anatomy since the dawn of time. The term “anatomy” is derived from the Latin anatemnein, which means “dissect” or “dismember”. Correspondingly, we owe most of our anatomical knowledge to the people who dissect the dead and make the functional units visible. By breaking down the body into its smallest units, we can understand its functions and connections and therefore the body as a whole. This means that anatomy is not only the basis for veterinary treatment, i.e. understanding which body part no longer works so that it can be fixed, but also the basis for correct riding.

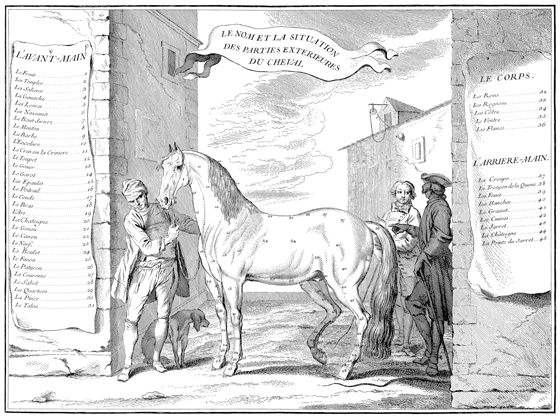

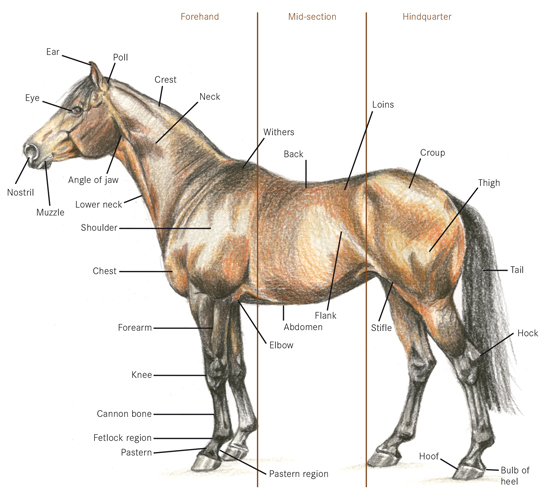

The points of the horse. (Illustration: Retsch-Amschler)

You will come across many Latin terms in this book, because Latin has always been the language of medicine. But don’t worry; it is not as difficult as it sounds! Some of these Latin names have already found their way into our language. For example, many riders will be familiar with the longissimus, the long back muscle that transfers the power of the hindquarters to the forehand, like an elastic band. Many of these terms are very flowery, such as os sacrale, the sacrum, whose name is derived from its cross shape. Others have arisen from comparative anatomy between the species. A musculus extensor (literally translated: extensor muscle) may also have a bending function, depending on how the joints are positioned in relation to one another in the animal concerned. Not all animals are unguligrades like horses, which walk on the tips of their toes like ballerinas. Many are digitigrades, such as cats or dogs, for example and some animals are plantigrades, such as human beings or badgers. Nevertheless, the same muscle always has the same name in all animals.

The Latin terms in this book will also enable you to understand your vet or equine osteopath better when they are discussing your horse’s health problems with you. We will also use non-Latin words in this book that have made their way into our language, such as knee joint or fetlock. Terms have been adopted into the language of riding that are not anatomically correct, such as “knee” for the carpal joint, which can lead to misunderstandings.

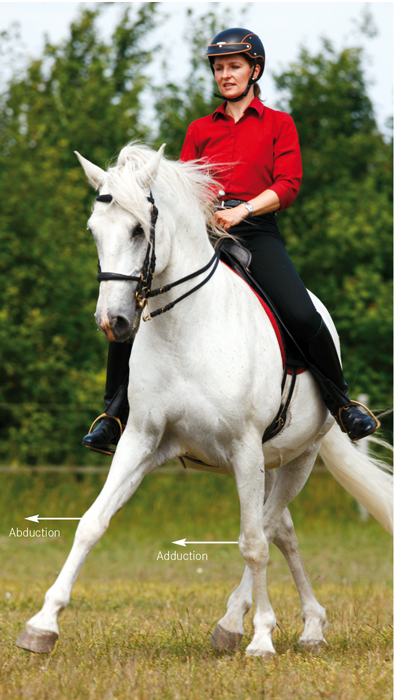

Terms that come both from the language of riding and the language of medicine are used to describe anatomy. In anatomy, the obvious English terms such as “above” or “below” are not used to describe directions, because these terms can change, for example, if the horse has to be turned onto its back for an operation. That is why we use Latin terms such as dorsal or ventral. In equitation we also use words to describe direction of movement. Adduction describes pulling the leg towards the midline and abduction describes the lateral stretching of the leg away from the midline. The adduction/abduction movement is particularly important for the half-pass.

The adduction/abduction movement can easily be recognised in the half-pass. (Photo: Slawik)

Flexion, i.e. upwards curving, of the back is the aim of all riding. In order for the back to flex, the sacrum, i.e. the end of the spinal column, and the pelvis, must tilt into a “sitting” position. This movement is also described as flexion. The opposite movement, i.e when the back is pushed down, is called extension, as is the movement of the pelvis and sacrum when stretching out the hindquarters.

We can clearly see how horses arch their backs when they buck. (Photo: Slawik)

This horse’s back is clearly extended. (Photo: Slawik)

An Overview of Anatomical Terms

Regions:

Forehand: All of the parts of the horse from the nose to the shoulder, including both front legs.

Midsection: The area between the forehand and the hindquarters, i.e. the back, chest and abdominal cavity with their respective organs.

Hindquarters: Everything behind the flank, i.e. croup and back legs.

Parts of the body:

Equine body parts have names very similar to human body parts: head, neck, shoulder, upper arm, forearm, back, abdomen, chest, hip and thigh. The only difference is that horses walk on four legs, i.e. on their hands and feet or, more precisely, on the tips of their toes. Everything below the knee joint or hock is called the “distal limb”.

Terms of location:

Cranial: Forwards or in the direction of the head. With regard to the head, we also say rostral for the direction of the nose or caudal for the direction of the ears.

Caudal: Backwards or towards the tail.

Dorsal: Upwards or towards the back.

Ventral: Downwards or towards the abdomen.

Medial: Towards the midline of the body. In the leg, this means the adduction movement.

Lateral: Sideways away from the midline of the body. In the leg, this means the abduction movement.

Anatomical Terms of Location. (Photo: Slawik)

The following terms also apply to the leg:

Proximal: In the direction of the body.

Distal: In the direction of the foot.

Palmar: The back of the foreleg, i.e. the “palm” side.

Plantar: The back of the hind leg, i.e. the “sole” side. The fronts of the legs, i.e. the back of the hand or the back of the foot, are described as “dorsal”.