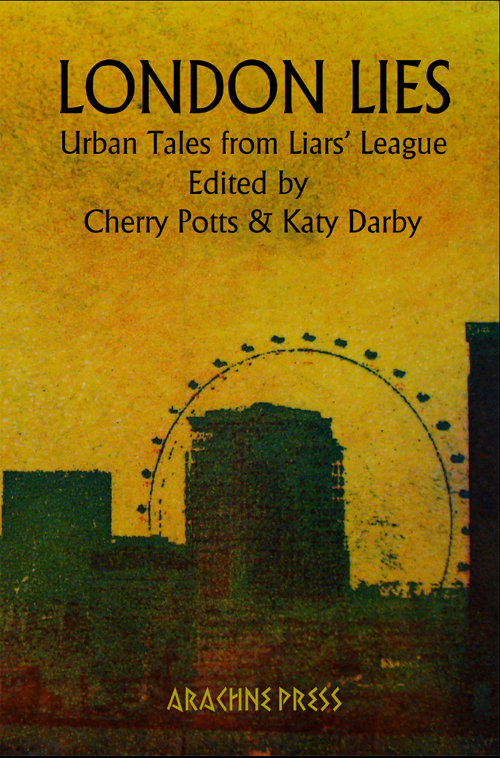

URBAN TALES FROM LIARS’ LEAGUE

EDITED BY

CHERRY POTTS AND KATY DARBY

The Suitcase - Rosalind Stopps

Thieves We Were - Simon Hodgson

Mark’s Fortunes: A Story In Nine Parts - Laura Williams

Keep Calm and Carry On - Katy Darby

Leaving - Cherry Potts

Incurable Romantic Seeks Dirty Filthy Whore - Martin Pengelly

Red - David Mildon

Palio - Liam Hogan

The Frog - Emily Cleaver

Made For Each Other - Nichol Wilmor

Truth, Music, and NikkiSexKitten - Jason Jackson

Ringtone - Harry Whitehead

The Runner - Alan McCormick

Telling It Like It Is - James Smyth

O Happy Day … - David Bausor

Are We Nearly There Yet? - Emily Pedder

Rat - Liam Hogan

The Escape - Emily Cleaver

Stained - Laura Martz

How to Win at Scrabble and Life - Clare Sandling

Girl With Palmettes - Martin Pengelly

Renewal - Joan Taylor-Rowan

Rosalind Stopps

It is everybody’s duty to be on the alert for terrorists and snipers in London these days, but as a senior assistant in a shoe shop in a large precinct, I am obviously used to living on the front line. Things are not necessarily what they seem, that’s the important thing to remember. You have to look behind the obvious for the extra something that might be lurking there, rather like when you meet someone’s boyfriend or husband.

‘This is Kevin,’ they might say, as if they are letting you in on one of life’s great secrets. You look up, expecting to see a handsome man or a kindly man, or better still, a mixture of the two, like David Attenborough, but instead, Kevin is standing there in an ill-fitting coat, looking like a man who sells lawn mowers in December. This hasn’t happened to me often, but one thing you may notice about me is that I have a great imagination. I am a woman who knows that when the scary side of life comes along, it will lurk behind something else, something with a smile and a bag of sweets to offer to small children.

I am good at anticipating lone gunmen. I can put myself right inside their heads, and imagine what could make them behave like that. They might have lost their job, for example, through no fault of their own. Someone might have spiked their drink at the office party, and taken photos of them with their trousers round their ankles, or spread vicious rumours about them, saying that they were too fat to have children, or had a gun at home when they didn’t, and that could have made them mad or sad enough to go and get one.

I felt like that at school, when everyone thought that I had stolen Carol Eliot’s rubber. It was shaped like a tortoise, and I admired it, I never denied that. I didn’t steal it though, I swear I didn’t, but I did steal some other people’s rubbers after that, just to show them what it was like. I cut most of them into pieces with a razor blade so I know a bit about regret, as well. I think I would make a good mother, full of insights and wisdom.

When I got on the underground train that morning at the Elephant and Castle, it was obviously me who noticed it first. Maureen was one step behind me, dithering with her Oyster card and calculating her fertile period, and she didn’t even notice anything unusual.

‘Unusual?’ I said, ‘That is a rather mild way of putting it.’ I can be a bit sarcastic, and I know that it is not the most polite thing to be, but a large unattended suitcase by the door of an underground train is a lot more than unusual.

‘It’s probably someone who forgot, and got off without it,’ Maureen said, which has to rank as one of the most stupid things I have ever heard her say. And believe me, there have been a few. Recently, she told me that the reason she and Kevin haven’t been able to get pregnant yet is because their bedroom faces south, and that can have a bad effect on the whole life force thing. Last month, it was because a pigeon had landed on her windowsill two mornings in a row.

‘Why would anyone leave a suitcase of that size?’ I asked. I have always been logical as well as imaginative, and I don’t take anything at face value. I’m not the kind of person who would allow a complete stranger to use the shop’s toilet, for example, even if they appeared to be in quite urgent need.

What I was thinking, which had obviously not struck Maureen, was that a lone crazed gunman could have left his gun in the case all ready to go on a killing spree, and sat in another carriage. I have always believed that a bit of preparation is necessary for most things – warming the teapot before putting the bags in, wearing loose boxers to let the sperm breathe, or buying a jacket with enough pockets to store the ammunition for a mass murder.

I looked at the suitcase more closely, not going too near just in case it was a bomb that had changed hands for vast amounts of money in the criminal world. Or a landmine, that someone might want to plant in a garden for revenge or even spite; there is no accounting for the lengths some people will go to. Last week I read a story in the newspaper about a man who threw acid on a small dog because his ex-wife had got to keep it. The dog had to be put down.

I stood back near the door as the train hurtled through the tunnel to Borough station, and leaned as far forward with my upper body as I could without falling. It looked like an ordinary suitcase. It had a dial at the top, the kind where you click it round to the right numbers and the case opens.

‘We’ll have to stop the train and call the police,’ I said, ‘they were very specific about that on the anti-terrorism leaflet that came to all the shops last year.’

Maureen didn’t look happy.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said and it was nice to be able to say something so helpful. ‘I’ll deal with it. I watched a programme about the bomb squad, and I think that the main thing is not to jolt it.’

Maureen looked so relieved that I stood up a bit taller. This must be what heads of families feel like, I thought, men and women with children, who bring home the food, fix the taps and unblock the drains. It must be like being on the first float in a bank holiday parade, with everyone clapping and shouting and babies waving small flags.

The carriage was empty apart from us, and I thought how lucky it was that Maureen and I are always so early. We have been the first retail assistants to arrive on the premises for 52 days out of the last 70, and we keep it written down in a little book in the staff room, in case anyone says that we are late. I suppose that will all change if Maureen does get pregnant.

I had some little socks in my pocket, the kind we use if someone comes in to the shop to try on shoes with bare feet. It’s obviously not appropriate, putting sweaty feet into brand new shoes that somebody else might end up spending quite a lot of money on, but you would be surprised at how many people try to do it, even people with noticeably poor foot hygiene. I thought about fingerprints and ignored the slight smell. Of course, they didn’t have fingers so it was like wearing mittens, but I really didn’t have much choice. I circled the suitcase to see where I could get the best grip, while Maureen hovered in the aisle stepping from foot to foot in her silver shoes as if it was a new dance that she had invented.

‘Go to the back of the carriage,’ I said, ‘in case anything goes wrong.’ I liked the feeling of being in charge for once. We’re supposed to be more or less equal in the shop, both paid the same, but she tends to boss me about a bit. I think it’s because she is married. I’ve noticed that about married people, there’s a kind of smugness about having a special person who thinks you are great that carries over into areas of your life where really, you are no better than anyone else. Maybe it is the promise of regular sex.

I decided not to touch the handle on the grounds that if I was going to booby trap a suitcase, I would make very sure that the handle was the trigger. Most people wouldn’t think of this, but I am not most people, so I kind of encircled the case in my arms like a sleepy child, and picked it up. It wasn’t heavy, and that was a surprise.

It was very important not to jolt the case at all. I stood up really gradually, moving my hands just a tiny bit to get a better grip, and cursing the slipperiness of the socks covering my fingers. The case felt as if it was empty except for one thing, and whatever that was shifted about a bit if I wasn’t very careful. No-one looked at me as I left the tunnel, Maureen following at a safe distance like a private detective on the trail of a cheating spouse. I balanced on the escalator and walked on tiptoes through London Bridge Station, locked in a sweaty embrace with the suitcase.

The bag seemed to shake a little by the pasty stand, or it might have been my hands slipping, and I almost dropped it in surprise. I felt proud that I managed not to. I thought that there might be a busload of pensioners just outside, or a party of tiny children in wheelchairs, and if the case was loaded with explosives they could be hurt. The only hope was to hang on, do one good thing regardless of my personal safety and hope that someone somewhere noticed. Maybe the man who worked in the shoe-mending kiosk would finally notice me, and although I would be sad to have been blown to pieces, the thought of him and others crying at the tragedy made it all seem a little more worthwhile. Who knows, maybe there would be a picture of me over the front of the station when they rebuilt it, or a small plaque in my memory. People would call their children ‘Barbara’ in the hope that they would one day be as daring, and as brave, and Maureen might see me in a different light.

I wanted to take the bag to the river, but I wasn’t at all sure which direction it was in. I am not the kind of person who asks for directions, even in an extreme situation, so we danced out of the front, the suitcase and I, past the black cabs and looking for signs of water. Not a sail or a mast in sight, and wherever the bridge had gone to it certainly wasn’t here. I am resourceful though, and I spotted a large skip, taller than me and over by the building works in the corner. There was a big chute going in to it like a children’s slide in an adventure playground, still quiet as if the children were all in bed. If I could hurl the case in and drop down flat to the pavement, I might still have a chance even if there was a bomb inside.

I whispered a quick goodbye to the case at the skip and raised it up above my head in slow motion, ready to throw and taking care not to jolt it any more than I could help. The noise of a city getting ready to face the day seemed to stop for a moment, and I wondered if this was the last time I would feel the pavement beneath my feet, or look up at the sun climbing over the docklands skyscrapers.

It was easier to throw than I thought, and I aimed well. There was a soft thud as it hit the bottom, and I wanted to drop to the floor but I settled for bending as if to do up my shoelaces instead, in case anyone was watching. I needn’t have worried. There was no flash, no explosion lighting the air like a memory of the Blitz. Just that soft thud and a tiny sound that could have been a cat, or a squeaky toy, and then all the cars seemed to start again, and I could hear an ambulance on its way to the hospital.

*

It was the ambulance that made me think of it. The ambulance going past, and the way that the suitcase in my arms had felt like someone I hadn’t met yet.

What if there’d been a baby in there, I thought, a real baby that somebody didn’t want? I wished that I hadn’t thrown it so hard or so far. The skip was too tall for me to climb in, and the station forecourt was starting to fill up like the opening scene in a play. If only I had been brave enough to open the case. I would have been so happy to see a baby, blinking in the light as if she had just come out of the cinema on a sunny afternoon. I could picture Maureen’s face, looking at me as if I was the best work colleague a woman could have.

We could have kept it in the shop, me and Maureen, made a little cradle from a shoebox and taken turns to feed it. The customers would have loved it, and I might have even been promoted to manager when central office heard how business had picked up.

I turned to give Maureen a thumbs up and heard a rumble as the first rubble of the day flew down the chute and covered the suitcase, until it was nothing more than a memory of what might have been.

Maureen and I went back into the station. We could still be at the shop before it opened if we caught the next train, and I have always thought that punctuality is vital in the shoe industry.

Simon Hodgson

In the spring that my father died, we walked through the confetti of Japanese cherry blossom in the Elsted churchyard after the ten o’clock service and he told me for the first time about the Reverend Norton Mudge.

Although my father didn’t talk about his childhood, I knew he’d grown up in the East End, that rabbit warren of brick-built houses thrown up after the Second World War. Patrick Delaney had been born in Bethnal Green, half a mile from York Hall, the fabled home of British boxing. One September night he’d taken me up to London on the train, to a smoky gymnasium where we’d sat three deep in the narrow gallery and watched lean white men, as pale and nervous as whippets, fight three rounds apiece.

It was smaller than I’d expected, and darker, a cavern smelling of Pall Mall cigarettes and sweat and the Vaseline smeared on the faces of the fighters. At the beginning and end of each bout, the announcer would clamber into the ring, a fat man in black trousers ducking awkwardly between the ropes as the crowd fell silent, and for a moment it felt like a church.

Reverend Mudge, Patrick said, appeared in Bethnal Green during the war and having earned his right to preach beneath the bomb bays of the Luftwaffe, he remained there for the next fifteen years. A Suffolk man, he found a home among the hotchpotch of Cockneys, Irish and Jews who attended his services. Anyone was welcome at St Mary’s, he joked, if only for the tea and biscuits afterwards.

Out of these quiet neighbourly mornings came the open house afternoons, in which parishioners laid on cakes and home-made lemonade in their front rooms. Mudge knew the value of his community and reached out to its most distant members: the broken; the begging; the walking wounded who wore medals on their overcoats even in summer; the unemployed; the needy; the mentally ill, whose smiles and sudden rages passed like clouds across the sun; the infirm; the elderly; even those to whom confession meant thirty feet of chain round the ankles and a five-fathom dip in the Thames.

Pinchbeck Wilson was his name. Pinch, they called him. The lord of the manor, the greatest gangster on the Hackney Road and the only man from whom my father ever stole. Wilson and Mudge were from opposite sides of the fence, in terms of the Good Book, but Pinch had heard about the clergyman’s service in the Blitz, carrying water, clearing rubble, conducting services in the gloom of Aldgate East tube station, four floors underground, as the lights flickered and flinched at the metal rain above.

Wilson himself had fought with some distinction in France and the Low Countries, although he lost any chance of medals after he was caught pilfering the regiment’s collection of captured German sidearms. According to dad’s friend Danny Harris, Pinch kept an entrenching tool from his time in France, with an edge whetted so sharp a man could see his own face in it before he died. Wilson once used the blade to sever an associate’s wrist tendons, then later to dig his grave in the marshes west of Purfleet. Nothing good ever came out of them marshes, Pinch used to say, but plenty of bad went in.

Stories of Pinch Wilson were legion in that part of London, my dad said, adding that most of them were probably myths. Other boys’ fathers told them tales of riches and robberies, of Wilson’s murderous associates. Of the hauls he’d made in the years following the war, when the police were more interested in public unrest than his quiet lorryloads of stolen goods. Of the strange old woman, some said Russian, or Hungarian, who hid him when the cops came looking.

Patrick’s dad told him no such tales. Hugh Delaney had confidence in his boy, sure that the lad would learn in his own time the difference between truth and lies. He was also tired. By the time my father was nine, Hugh was already a widower of 51, only a greying whisker short of Norton Mudge’s age. He’d survived the war, survived the army and made it home only for his bride to die three years later of an infection caused by inhaling the concrete dust and smoke from the charred urban rubble. He was not a talkative father, but he did give his son one piece of advice.

‘Never take anything he offers you.’

Even aged nine, Patrick knew what that meant. Pinch Wilson was a generous man, but somehow, all his gifts came back to him. Eddie O’Neill, the bookie on Mare Street, at the very edge of Pinch’s territory, had over-extended himself a few years back. Pinch offered him a loan, ‘to get yourself back on your feet’. He now owned the book-makers, while Eddie drank for a living at The Green Man on Cambridge Heath Road.

Or Albert Isen, the publican: he ran The Earl Grey, until Pinch went halves with him. Inside six months, Albert found out that his share was nearer a quarter and some Fridays, not even that. After his teenage son was braced one night under the railway bridge, he sold his share in the pub and moved east to Essex. Pinchbeck Wilson threw him a leaving bash to remember and pulled pints of Fuller’s London Pride ’til two in the morning.

He drove a Jaguar Mark II the colour of day-old blood and when he parked on the road, kids from three streets away would cluster around and listen with open eyes to the engine ticking as it warmed down. Scallies, he called them, scallywags, a remnant of Glaswegian slang from a stint in the Bar-L. Wilson had been nicked up in Scotland, claimed Brendan, while taking car parts off a ship in the Clyde. Brendan’s father was from Falkirk and knew about these things.

That profitable northern enterprise nearly earned Wilson four thousand pounds for nine hours work, but instead cost him two and a half years as a guest of Her Majesty in Barlinnie, the toughest prison in Scotland. The time wasn’t wasted. Pinch made contacts inside, contacts he sent for when he got back to London. Which is how Murdo McLean, who’d done two years for assault, two for extortion and four for armed robbery, happened to be passing out custard creams at Reverend Mudge’s parish party.

Once a year, Pinch Wilson would open his doors to Bethnal Green. Not all the doors, my father added. Guests were allowed in the back garden, the front room and the kitchen – Mudge called it ‘the parlour’ when he informed the children who’d turned up mob-handed. Most of the two-storey houses in Hackney Borough had a passageway so you could walk from the street to the garden, but Pinch’s house had a heavy wooden door with a lock and no spaces between the slats for peeking. This from Danny Harris, who’d tried exactly that.

The garden was a balding square of grass with a six-foot brick wall at the end that backed onto the knobbled alleyway where the lock-ups and garages were. Two or three kids were kicking a stone between them, watched carefully by Murdo, when my father went into the kitchen.

‘Can I help ya, son?’ Murdo materialised from behind him, blocking out the light from the garden. He wasn’t a tall man, perhaps only five foot nine, but he was wide. Broad in the chest, thick in the neck and the wrist and the ankle. McLean was muscle, used mostly by Wilson for show, occasionally for heavier work. He was built, my father said with an apologetic wrinkle of his eyebrow, like a brick shithouse. He told Murdo he was looking for the toilet.

‘Doon the hall fust door on the right.’ But Patrick Delaney didn’t go right. He opened the door on the left to Pinch Wilson’s study, opening it just enough to slip through and into a room darkened by the closed curtains. Before him was a desk with envelopes and a black fountain pen, three drawers on the right side.

By the door, a small cabinet with shelves: files on the bottom, a clawhammer beside a green Lyle’s Golden Syrup tin filled with nails, a few paperbacks, two rings of keys and a pair of calfskin gloves in fine brown leather. On the top shelf was a tin of Tom Long ‘grand old rich tobacco’, a silver hip flask, four tickets to a show at the Royal Court theatre on Sloane Square, and Pinchbeck Wilson’s entrenching tool.

It was heavier than Patrick expected, spade-shaped, but smaller, with a worn wooden handle as long as a pencil and a silver blade that tapered to a sharp edge. On the back were words he recognised as German, but he didn’t know what they said. He held it in both hands, feeling its heft, then lifted it up to his face. There was no reflection, or was that just the darkness? He put it back on the shelf and slipped the hip flask into his pocket.

Patrick rejoined the little crew in the garden and opened his palms to show the Garibaldi biscuits he’d swiped from the kitchen table.

‘Thanks Mr Wilson.’

‘Any time, Patrick.’ Pinch Wilson leaned down to shake his hand and Patrick could see the blotches and bumps on his jaw. It looked like a road that hadn’t been rolled flat yet, something not finished, not entirely civilised. Wilson kept hold of his hand and Patrick had a terrible feeling that he could smell the metal on his skin.

‘You want something, you let me know.’ Pinch smiled, and his lips drew back from his teeth. ‘Any time.’

The other boys were waiting for him by the kerb, beside the Jaguar. Davie joined them after a moment and as they turned to walk home, or play football, or share the Rich Tea biscuits which Danny and Arthur had stuffed in their pockets, Patrick looked back and saw Murdo watching them.

That was the last parish party my father attended at Pinchbeck Wilson’s, he told me. He never used the hip flask, never told a soul until today, he said. It was March and he was dying and though there were robins and thrushes singing in the bony trees, his breath formed thin clouds, each wisp one fewer.

He thought it would feel different, he said, sweet as a mug of tea with too many sugars. Not to take what Pinch offered, but to steal it. When he got home though, he was afraid. Afraid of his father and his one warning, afraid of the German entrenching tool, afraid of Pinchbeck Wilson and the menace of ‘any time’.

He felt the eye of Murdo McLean on his back and when he swallowed, he tasted metal.