Love your patients and they will do anything that you ask.

Ann Felton (1942–2007)

Ann Felton made people smile and their smiles brighter. Ann was a dental hygienist, tutor and mentor, and ran her own oral health education course for dental nurses whom she referred to as ‘the darlings of dentistry’.

Ann wrote the majority of this book in difficult circumstances, yet retained her love for the subject and sense of humour throughout. This text is dedicated to Ann’s life and work in making people smile.

This edition first published 2009

@ 2009 A. Felton, A. Chapman, & S. Felton

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007.

Blackwell’s publishing programme has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial offices

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, United Kingdom

2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Felton, Ann.

Basic guide to oral health education and promotion / Ann Felton, Alison Chapman;

edited by Simon Felton.

p.; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-6162-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Dental health education.

2. Health promotion. I. Chapman, Alison, II. Felton, Simon, 1970– III. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Health Education, Dental – methods. 2. Dental Assistants. 3. Health

Promotion – methods. WU 113 F326 2009]

RK60.8.F45 2009

617.6′01 – dc22

2008039842

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

2 2010

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

SECTION 1: Structure and Functions of the Oral Cavity

Chapter 1 The oral cavity in health

INTRODUCTION

MAIN FUNCTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY

TEETH

THE TONGUE AND THE FLOOR OF THE MOUTH

SALIVA

REFERENCES

SECTION 2: Diseases and Conditions of the Oral Cavity

Chapter 2 Plaque, calculus and staining

INTRODUCTION

PLAQUE

CALCULUS

STAINING

REFERENCES

Chapter 3 Chronic gingivitis

WHAT IS CHRONIC GINGIVITIS?

REFERENCE

Chapter 4 Chronic periodontitis

WHAT IS CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS?

REFERENCES

Chapter 5 Other common oral diseases and conditions

INTRODUCTION

PERIODONTAL ABSCESS

MOUTH ULCERS (APHTHOUS ULCERATION)

COLD SORES (HERPES LABIALIS)

ACUTE HERPETIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS

NECROTISING ULCERATIVE GINGIVITIS (NUG)

AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS (AP)

LOCALIZED AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS (LAP)

ORAL CANDIDOSIS

WHITE PATCHES (LEUKOPLAKIA)

LICHEN PLANUS

RED PATCHES

ORAL CANCER (CARCINOMA)

ACQUIRED IMMUNE DEFICIENCY SYNDROME (AIDS)

RECREATIONAL DRUG USERS

DIABETES

CROHN’S DISEASE AND COLITIS

REFERENCES

Chapter 6 Caries

WHAT IS CARIES?

REFERENCES

Chapter 7 Tooth surface loss and sensitivity

WHAT IS TOOTH SURFACE LOSS?

SENSITIVITY (DENTINE HYPERSENSITIVITY)

REFERENCES

Chapter 8 Xerostomia

WHAT IS XEROSTOMIA?

REFERENCES

SECTION 3: Oral Disease Prevention

Chapter 9 Food, glorious food

INTRODUCTION

REFERENCES

Chapter 10 Sugars in the diet

INTRODUCTION

THE COMA PANEL ON DIETARY SUGARS (REMEMBER!)

THE NACNE REPORT (REMEMBER!)

REFERENCES

Chapter 11 Fluoride

WHAT IS FLUORIDE?

REFERENCES

Chapter 12 Fissure sealants

WHAT IS A FISSURE SEALANT?

REFERENCES

Chapter 13 Smoking cessation

INTRODUCTION

REASONS WHY PEOPLE SMOKE

EFFECTS OF TOBACCO SMOKING ON GENERAL HEALTH

EFFECTS OF TOBACCO SMOKING ON ORAL HEALTH

HELPING PATIENTS CHANGE SMOKING HABITS

REFERENCES

SECTION 4: Delivering Oral Health Messages

Chapter 14 Communication

WHAT IS COMMUNICATION?

COMMUNICATION IN THE DENTAL SURGERY

MEDIA INFLUENCE

TECHNOLOGY AND THE OHE

Chapter 15 Principles of education

INTRODUCTION

EDUCATIONAL THEORISTS

THE THREE DOMAINS OF LEARNING

STRUCTURING A LESSON

SO WHAT IS A QUESTIONNAIRE?

REFERENCES

Chapter 16 Setting up a preventive dental unit (PDU)

INTRODUCTION

PDU LOCATION

PDU DESIGN

SETTING UP DISPLAYS

ORGANISATION

REFERENCES

Chapter 17 Planning an oral hygiene session

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 18 Anti-plaque agents

WHAT ARE ANTI-PLAQUE AGENTS?

TOOTHPASTE

ANTI-PLAQUE MOUTHWASHES

SUGAR-FREE CHEWING GUM

REFERENCES

Chapter 19 Practical oral hygiene instruction

INTRODUCTION

TEACHING PLAQUE CONTROL SKILLS

REFERENCES

SECTION 5: Oral Health Target Groups and Case Studies

Chapter 20 Pregnant and nursing mothers

INTRODUCTION

THE ROLE OF THE OHE

SUSCEPTIBILITY TO ORAL DISEASES AND CONDITIONS

SUMMARY OF ADVICE FOR PREGNANT WOMEN

REFERENCES

Chapter 21 Parents of pre-11-year-olds

INTRODUCTION

ADVICE TO PARENTS OF O–2-YEAR-OLDS

ADVICE TO PARENTS OF CHILDREN AGED 2–5 YEARS

ADVICE TO PARENTS OF CHILDREN AGED 6–11 YEARS

REFERENCES

Chapter 22 Adolescents and orthodontic patients

ADOLESCENTS

THE ORTHODONTIC PATIENT

REFERENCES

Chapter 23 Older people

WHO ARE OLDER PEOPLE?

REFERENCES

Chapter 24 At risk and special care patients

WHO ARE ‘AT RISK’ PATIENTS?

REFERENCES

Chapter 25 Minority ethnic populations in the UK

INTRODUCTION

BARRIERS TO DENTAL TREATMENT

BREAKING DOWN THE BARRIERS

GUIDELINES FOR PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL

REFERENCES

Chapter 26 Other health professionals

INTRODUCTION

WHO ELSE PROVIDES ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION?

GAINING CONFIDENCE TO DELIVER ADVICE TO OTHER PROFESSIONALS

GIVING ADVICE TO INDIVIDUAL HEALTH EDUCATION PROFESSIONALS

REFERENCES

Chapter 27 Planning education case studies

RECORD OF EXPERIENCE

REFERENCE

SECTION 6: Oral Health and Society

Chapter 28 Sociology

SOCIOLOGY

SOCIALISATION

THE ICEBERG EFFECT

REFERENCES

Chapter 29 Epidemiology

WHAT IS EPIDEMIOLOGY?

SURVEYS

INDICES

REFERENCES

Chapter 30 Evidence-based prevention

PREVENTION IS BETTER THAN CURE

REFERENCES

Chapter 31 UK dental services

GENERAL DENTAL SERVICE

HISTORY OF PRIVATE DENTAL PRACTICES

COMMUNITY DENTAL SERVICE (CDS)

HOSPITAL DENTAL SERVICE

REGULATIONS GOVERNING DENTISTRY

REFERENCES

Chapter 32 Oral health promotion

WHAT IS ORAL HEALTH PROMOTION?

THE OTTAWA CHARTER

DEFINING PEOPLE’S NEEDS

WHY DOES INCREASING KNOWLEDGE NOT CHANGE BEHAVIOUR?

REFERENCES

Index

Ann Felton and Alison Chapman have between them more than 30 years of experience in the delivery and training of oral health education. Ann designed, and has run with Alison, an exceptionally successful oral health education course in Bristol for over 10 years, with a pass rate of over 95% in the UK national examination.

This has given them great experience and understanding of the subject and the needs of students. The delivery of dental care is undergoing fundamental changes and the need to develop practice teams with skill mix makes this book very timely. Practices may well need to consider how they can make best use of their staff to help deliver oral care to their patients in the future, and oral health educators could well become an important part of this process.

This book provides a most comprehensive review of the subject. Each chapter has clearly defined learning outcomes that make it easy to read and understand. It is an ideal revision aid and basis for any member of the dental team and other health professionals wishing to know about all the aspects of oral health education. It would also be a good reference book for all practices on the subject.

Oral health is central to our general well-being. The health of the body begins with the oral cavity, since all our daily nutrients, beneficial or otherwise, pass through it.

Knowledge in the field of oral health is changing rapidly and there is a great deal to learn. Patients need trained oral health educators (OHEs) and promoters to help prevent and control dental conditions and disease. It is vital that dental and health professionals consistently promote the same messages to avoid confusion and ultimately improve oral health within the population.

This book covers the theoretical and practical aspects of oral health education and promotion, and is the course companion for UK dental nurses studying for the NEBDN Certificate in oral health education. It is also aimed at hygienists, therapists and dentists who regularly promote and practise oral health and require up-to-date, evidence-based knowledge (including professionals and trainees in developing nations where education has proven to be a cost-effective method of improving oral health). Other professionals such as health visitors, nurses, dieticians and midwives will also find the book invaluable.

Each chapter deals with various aspects of oral health and follows the NEBDN syllabus in a logical order that will also suit other professionals who may ‘dip into’ relevant chapters of interest. Chapters begin with learning outcomes, detailing what the reader should have learnt by the end of the chapter, and conclude with self-assessment exercises. Where the word ‘Remember!’ appears in the text, it highlights a point particularly relevant to NEBDN students. After reading this book, the reader should be able to:

SECTION 1

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY

This section comprises a revision chapter, which looks at the oral cavity in some detail. The structure of the tooth and its supporting tissues are examined, plus the eruption dates of primary and secondary dentitions.

The tongue, its functions in maintaining oral health, common conditions associated with it, and the composition and role of saliva in keeping the mouth healthy conclude the chapter.

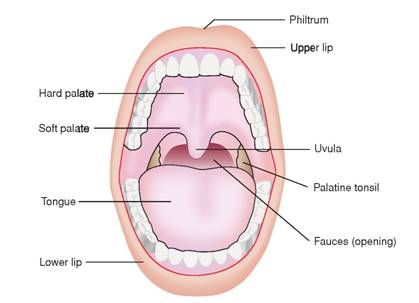

Before oral health educators (OHEs) can deliver dental health messages to patients, and confidently discuss oral care and disease with them, they will need a basic understanding of oral cavity anatomy (Figures 1.1 and 1.2) and how the following structures within it function:

The oral cavity is uniquely designed to carry out two main functions:

Figure 1.1 Structure of the oral cavity (© Elsevier 2002. Reproduced with permission from Reference 1)

Figure 1.2 A healthy mouth (© Blackwell Publishing 2003. Reproduced with permission from Reference 2)

Different types of teeth are designed (shaped) to carry out different functions. For example: canines are sharp and pointed for gripping and tearing food, while molars have flatter surfaces for chewing. Tooth form in relation to function is known as morphology.

Dental nurses and health care workers may remember from their elementary studies that there are two types of dentition (a term used to describe the type, number and arrangement of natural teeth).

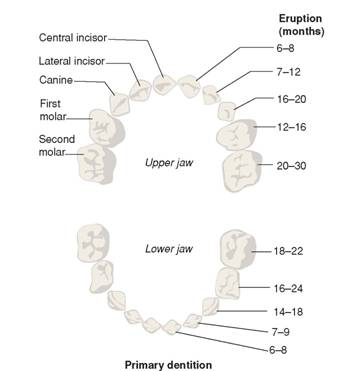

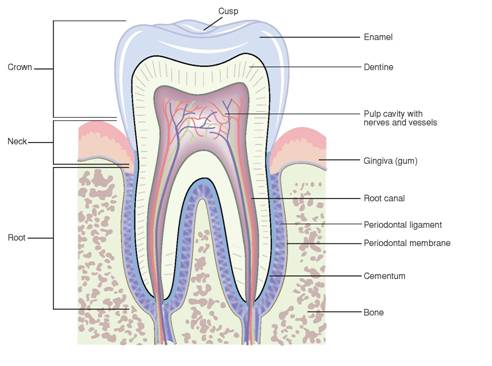

There are three types of deciduous teeth that make up the primary dentition (Figure 1.3): incisors, canines and molars (first and second). Table 1.1 details their notation (the code used by the dental profession to identify teeth), approximate eruption dates and functions.

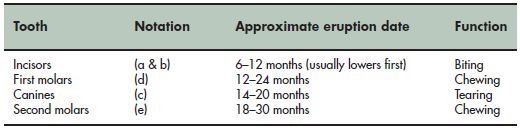

There are four types of permanent teeth that make up the secondary dentition (Figure 1.4): incisors, canines, premolars and molars. Table 1.2 details their notation, approximate eruption dates and functions.

It is important to remember that these eruption dates are only approximate and vary considerably in children and adolescents. The OHE should be prepared to answer questions from parents who are worried that their child’s teeth are not erupting at the same age as their friends’ teeth. Parents often do not realise, for example, that no teeth fall out to make room for the first permanent molars (sixes), which appear behind the deciduous molars.

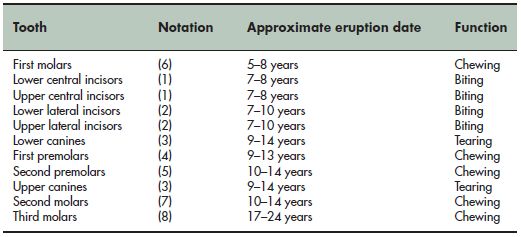

Tooth structure (Figure 1.5, see page 10) is complex and comprises several different hard layers which protect a soft, inner pulp (nerves and blood vessels).

The words organic and inorganic are often mentioned in connection with tooth structure. OHEs must know what these terms mean and their percentages in hard tooth structures.

Figure 1.3 Primary dentition (© Elsevier 2002. Reproduced with permission from Reference 1)

Organic means living and describes the matrix (framework) of water, cells, fibres and proteins which make the tooth a living structure.

Inorganic means non-living and describes the mineral content of the tooth which gives it its strength. These minerals are complex calcium salts. (Remember! calcium hydroxyapatite.)

Table 1.3 shows the percentages of organic and inorganic matter in hard tooth structures.

Table 1.1 Primary dentition (notation, approximate eruption dates and functions)

Figure 1.4 Secondary dentition (© Elsevier 2002. Reproduced with permission from Reference 1)

Table 1.2 Secondary dentition: notation, approximate eruption dates and functions

Figure 1.5 Structure of the tooth (© Elsevier 2002. Reproduced with permission from Reference 1)

It is also important that the OHE knows basic details about these three hard tooth substances, and also pulp.

Enamel is made up of prisms (crystals of hydroxyapatite) arranged vertically in a wavy pattern, which give it great strength. The prisms, which resemble fish-scales, are supported by a matrix of organic material including keratinised (horny) cells and can be seen under an electronic microscope.

Table 1.3 Percentages of organic and inorganic matter in hard tooth structures

| Structure | Inorganic | Organic |

| Enamel | 96% | 4% |

| Dentine | 70% | 30% |

| Cementum | 45% | 55% |

Enamel is:

Enamel is also subject to four types of wear and tear. The OHE needs to be aware of these and be able to differentiate between them:

Dentine constitutes the main bulk of the tooth and consists of millions of microscopic tubules (fine tubes), running in a curved pattern from the pulp to the enamel on the crown and the cementum on the root.

Dentine is:

Cementum covers the surface of the root and provides an attachment for the periodontal ligament. The fibres of the ligament are fixed in the cementum and in the alveolar bone (see supporting structures of the tooth).

Cementum is:

Pulp is a soft living tissue within the pulp chamber and root canal of the tooth. It consists of blood vessels, nerves, fibres and cells. The pulp chamber shrinks with age as more secondary dentine is laid down, so that the tooth becomes less vulnerable to damage.

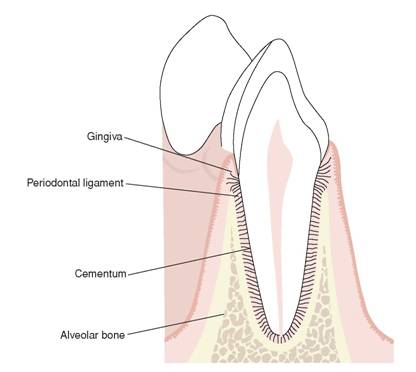

The periodontium (Figure 1.6) is the collective name for the supporting structures of the tooth. It comprises:

The periodontal ligament (or membrane) is a connective tissue which holds the tooth in place in the alveolar bone (assisted by cementum). The ligament is between 0.1 and 0.3 mm wide4 and contains blood vessels, nerves, cells and collagen fibres.

The collagen fibres attach the tooth to the alveolar bone and run in different directions, which provide strength and flexibility and act as a shock absorber for the tooth; teeth need to move slightly in their sockets in order to withstand the pressures of mastication (chewing). Imagine what it would feel like to bite hard with teeth rigidly cemented into bone.

Figure 1.6 The periodontium (© Blackwell Publishing 2003. Reproduced with permission from Reference 3)

Alveolar bones are horseshoe-shaped projections of the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw). They provide an attachment for the fibres of the periodontal ligament and sockets for the teeth.

The gingivae (gums) consist of pink-coloured mucous membranes and underlying fibrous tissue, covering the alveolar bone.

Gingivae are divided into four sections:

Figure 1.7 Free and attached gingiva (© Blackwell Publishing 2003. Reproduced with permission from Reference 2)

The tongue is a muscular, mobile organ which lies in the floor of the mouth, and comprises four surfaces:

There are two groups of tongue muscles:

The main functions of the tongue are taste, mastication, deglutition (swallowing), speech, cleansing and protection.

The tongue (and other parts of the oral cavity) is covered with taste buds that allow us to distinguish between sweet, sour, salt and savoury tastes. An adult has approximately 9000 taste buds4, which are mainly situated on the upper surface of the tongue (there are also some on the palate and even on the throat).

The tongue helps to pass a soft mass of chewed food (bolus) along its dorsal surface and presses it against the hard palate.

The tongue helps pass the bolus towards the entrance of the oesophagus.

Tongue movement plays a major part in the production of different sounds.

Tongue muscles allow for tremendous movement, and the tongue can help to remove food particles from all areas of the (mouth mainly using the tip).

The tongue moves saliva (which has an antibacterial property) around the oral cavity.

The following conditions affect the tongue:

Piercing of the tongue can also cause problems and the OHE should be able to advise patients on this matter. Tongue cleansing is also back in vogue, due to an increased awareness of halitosis6, and tongue cleansers (e.g. TePe®) can help with this condition.

The OHE need only know that the floor of the mouth consists of a muscle called the mylohyoid and associated structures.

Incredible stuff, saliva! It is often taken for granted, and patients only realise how vital it is to the well-being of the oral cavity and the whole body, when its flow is diminished.

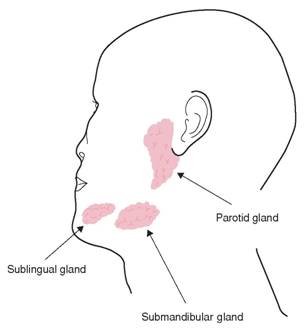

Saliva is secreted by three major and numerous minor salivary glands. The minor glands are found in the lining of the oral cavity; on the inside of the lips, the cheeks, the palate and even the pharynx.

The three major salivary glands (Figure 1.8):

Figure 1.8 Major salivary glands (© Fejerskov & Kidd. Reproduced with permission from Reference 7)

Saliva is made up of 99.5% water and 0.5% dissolved substances4. Dissolved substances include:

There are eight main functions of saliva:

Here are some general points of interest about saliva:

Although saliva entering the mouth is sterile, it soon loses this property as it collects organic material already present, including:

1. Thibodeau, G.A., Patton, K.T. (2002) Anatomy and Physiology, 5th edn. Mosby, Missouri, USA.

2. Lang, N.P., Mobelli, A., Attström, R. (2003) Dental Plaque and Calculus. In Lindhe, J., Karring, T., Lang, N.P. (Eds): Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, 4th edn, pp. 81–105. Blackwell Munksgaard, Oxford.

3. Lindhe, J., Karring, T., Araújo, M. (2003) Anatomy of the Periodontium. In Lindhe, J., Karring, T., Lang, N.P. (Eds): Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, 4th edn, pp. 3–49. Blackwell Munksgaard, Oxford.

4. Collins, W.J., Walsh, T., Figures, K. (1999) A Handbook for Dental Hygienists, 4th edn. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

5. Cawson, R.A. (1981) Aids to Oral Pathology and Diagnosis, Churchill Livingstone (Medial Division of Longman Group), Edinburgh.

6. Tilling, E. (2007) Xerostomia, Your Patients and You. Lecture given at Gloucester Independent Hygienists’ Study Day, Berkley, Gloucestershire, 16 March 2007.

7. Fejerskov, O., Kidd, E. (Eds) (2003) Dental Caries: The Disease and its Clinical Management. Blackwell Munksgaard, Oxford.

SECTION 2

DISEASES AND CONDITIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY

This section explores the reasons for, and the effects of, the breakdown of oral health, and details advice that should be given to patients to prevent disease and restore a good standard of oral health.

There is, of course, no brief answer. The determinants are many and complex, and more often than not a combination of factors are involved in the development of a particular condition or disease: cultural, environmental, socioeconomic, diet and lifestyle (the latter has much to answer for). Education in these areas is thus vital in controlling dental disease.

Oral health educators (OHEs) need an understanding of plaque and calculus, and their roles in the development of common dental diseases such as caries, gingivitis and periodontitis.

Most people have heard of plaque, but few would be able to explain its composition.

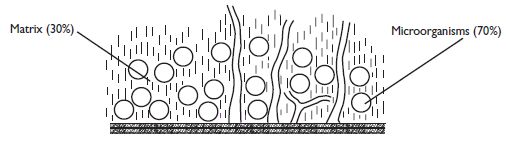

Plaque is a substance containing bacteria and debris, which collects on the surfaces of teeth (Figure 2.1). Even in people with good toothbrushing skills, one would need to brush and floss approximately every 3 min in order to prevent plaque from forming (M. Midda, personal communications).

The most common sites where plaque is found are occlusal pits and fissures, cervical margins of the teeth, and in periodontal pockets.

Figure 2.1 Plaque (© Carole Hollins. Reproduced with permission from Reference 1)

Saliva plays a large part in the formation of plaque. It is a complex fluid and contains many nutrients of blood, which continually coat a transparent film of glycoproteins (complex sugars and proteins) over the teeth. This film is known as the salivary pellicle, and the mucous it contains makes it sticky and difficult to remove.

Within a few hours after brushing the salivary pellicle is colonised by millions of microorganisms (both ‘good and bad’), which feed on sugars and starches present, although plaque bacteria can multiply to a lesser degree without this substrate. At any given time, there are around 300 species and several hundred billion microorganisms in the oral cavity2.

In a healthy mouth the ‘good guys’ kill off the ‘baddies’, but when illness or antibiotics (for example) upsets the balance of the mouth’s flora, or when teeth are not cleaned often and/or appropriately, the villains can get the upper hand. Bacteria are the first microorganisms to colonise the salivary pellicle, and form a large colony within 3 h following toothbrushing. This colonised salivary pellicle constitutes early plaque.

Bacteria are classified by whether they need oxygen or not to survive and the colour that they stain in laboratory tests (known as Gram’s staining).

The majority of bacteria in a healthy mouth come from the oxygen-dependent (aerobic) streptococci group which colonise areas of the mouth where oxygen is readily available. When resistance is lowered they can give rise to sore throats and other illnesses, but are less harmful than their non-oxygen-dependent (anaerobic) relatives4.

Aerobic bacteria are also known as gram-positive bacteria (staining blue/purple after the application of dye).

The most common species of streptococci (Sing. Streptococcus) bacteria found in the oral cavity are:

Aerobic bacteria feed on sucrose from the human diet, and in doing so, produce sticky substances that enable other more harmful organisms to attach themselves, causing plaque to become more dense and harmful to tissues within hours.

The more pathogenic (disease causing) bacteria do not need oxygen to survive and can hide in areas of the mouth such as periodontal pockets, which render them difficult to remove. They are also often known as gram-negative bacteria (staining red/pink after the application of dye).

Examples of gram-negative bacteria are:

Poor plaque removal is the primary cause of mature plaque. When plaque is left on teeth (often when they are cleaned ineffectively), it begins to mature – bacteria numbers increase and more harmful microorganisms appear – and it becomes increasingly harmful to both hard and soft tissues.

Figure 2.2 Mature plaque (© Ruth McIntosh. Reproduced with permission)

Mature plaque (Figure 2.2) consists of:

After 24 h without brushing, a clinically detectable layer of plaque is formed. As this matures, gram-negative bacteria vastly increase in numbers, organising themselves into colonies. These colonies make up the biofilm, which has been likened to communities within cities4. The inhabitants share resources and repel ‘invaders’, which individually they would be unable to do. If this plaque is not removed after 7–10 days, microorganisms present will include aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, viruses and fungi.

Anaerobic bacteria produce enzymes and toxins. These potentially harmful substances can cause gingivitis and subsequently periodontitis.

Fungi such as Candida albicans (oral thrush) are commonly found in plaque. As with bacteria, these do not affect oral health unless the body’s resistance is lowered and the immune system is upset.

The most common virus in the oral cavity is herpes simplex, which gives rise to cold sores.

As well as providing an abundant food source for bacteria, the salivary pellicle also collects any other debris present in the mouth which forms the matrix (in which the colonising bacteria feed and reproduce).

The following substances make up the matrix:

The importance of the following secondary factors in the retention of plaque (and therefore in the development of dental disease) should not be underestimated:

The following measures should be taken to prevent the build-up of plaque:

Remember! The enzymes and toxins of anaerobic bacteria in mature plaque are the primary causes of gingivitis and periodontitis.

Calculus