CONTENTS

PREFACE TO SERIES

PREFACE

CONTRIBUTORS

PART 1: PROPERTIES AND REACTIONS OF CARBENES

1 CARBENE STABILITY

1.1 INTRODUCTION

1.2 BACKGROUND

1.3 CARBENE STABILITY

1.4 CORRELATIONS INVOLVING CARBENE STABILITY

1.5 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

2 STABLE CARBENES

2.1 INTRODUCTION

2.2 TYPES OF STABLE CARBENES

2.3 SPECTROSCOPIC CHARACTERISTICS

2.4 CHEMICAL REACTIVITY

2.5 CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

3 ACID–BASE CHEMISTRY OF CARBENES

3.1 INTRODUCTION

3.2 SOLUTION pKasOF THE CONJUGATE ACIDS OF CARBENES

3.3 GAS-PHASE BASICITIES AND PROTON AFFINITIES OF CARBENES

3.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

4 COMPUTATIONAL METHODS FOR THE STUDY OF CARBENES AND THEIR EXCITED STATES

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 CARBENES

4.3 REARRANGEMENT IN EXCITED STATES (RIES)

4.4 ADVANCES IN COMPUTATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS OF CARBENES

4.5 THEORETICAL STUDIES OF THE PHOTOCHEMISTRY OF CARBENE PRECURSORS

4.6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

5 DYNAMICS IN CARBENE REACTIONS

5.1 INTRODUCTION

5.2 DYNAMICS OF CARBENE CYCLOADDITIONS TO ALKENES AND ALKYNES

5.3 DYNAMICS OF OTHER CARBENE-MEDIATED REACTIONS

5.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

6 ULTRAFAST KINETICS OF CARBENE REACTIONS

6.1 INTRODUCTION

6.2 ULTRAFAST UV-VIS STUDIES OF THE INTERMOLECULAR REACTIVITY OF p-BIPHENYLYLCARBENE (BpCH)

6.3 REARRANGEMENTS IN THE EXCITED STATE OF THE CARBENE PRECURSOR

6.4 DYNAMICS OF CARBENE VIBRATIONAL COOLING AND SOLVATION

6.5 INFLUENCE OF SOLVENT ON CARBENE INTERSYSTEM CROSSING RATES

6.6 ELECTRONICALLY EXCITED (OPEN SHELL) SINGLET CARBENES

6.7 PARENT PHENYLDIAZIRINE—MECHANISTIC ASPECTS OF SINGLET CARBENE FORMATION

6.8 INFLUENCE OF HALO-SUBSTITUENT ELECTRON-DONATING CAPACITY ON DIAZIRINE DECAY IN THE FIRST EXCITED SINGLET STATE

6.9 THE INFLUENCE OF EXCITATION WAVELENGTH ON THE PHOTOCHEMISTRY OF DIAZIRINES

6.10 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

7 TUNNELING IN THE REACTIONS OF CARBENES AND OXACARBENES

7.1 INTRODUCTION: LIGHT- AND HEAVY-ATOM TUNNELING

7.2 ALKYL- AND HALOCARBENES

7.3 THE FORMOSE REACTION AND HYDROXYCARBENES

7.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

8 CARBODICARBENES

8.1 INTRODUCTION

8.2 CARBODICARBENES WITH N-HETEROCYCLIC LIGANDS C(NHC)2

8.3 TETRAAMINOALLENES AND “HIDDEN” CARBODICARBENES

8.4 BENT ALLENES

8.5 RELATED COMPOUNDS

8.6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

9 CATALYTIC REACTIONS WITH N-MESITYL-SUBSTITUTED N-HETEROCYCLIC CARBENES

9.1 INTRODUCTION

9.2 THE N-MESITYL GROUP: A MECHANISTIC ASPECT

9.3 NHC CATALYSIS BY CLASS OF REACTIVE INTERMEDIATES

9.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

10 SUPRAMOLECULAR CARBENE CHEMISTRY

10.1 INTRODUCTION

10.2 TYPES OF HOSTS USED IN SUPRAMOLECULAR CARBENE CHEMISTRY

10.3 CHOOSING THE RIGHT CARBENE GUEST

10.4 DIAZIRINES AS SUITABLE SUPRAMOLECULAR CARBENE PRECURSORS

10.5 ARCHITECTURE OF THE GUEST@HOST COMPLEX

10.6 CASE STUDIES

10.7 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

PART 2: METAL CARBENES

11 MODERN LITHIUM CARBENOID CHEMISTRY

11.1 INTRODUCTION

11.2 STRUCTURAL FEATURES OF LITHIUM CARBENOIDS

11.3 LITHIUM HALIDE CARBENOIDS

11.4 STRUCTURE–REACTIVITY RELATIONSHIPS

11.5 LITHIUM–OXYGEN CARBENOIDS

11.6 LITHIUM–NITROGEN CARBENOIDS

11.7 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

12 RHODIUM CARBENES

12.1 INTRODUCTION

12.2 OVERVIEW OF RHODIUM–CARBENOID INTERMEDIATES AND CHIRAL CATALYSTS

12.3 ENANTIOSELECTIVE CYCLOPROPANATION

12.4 CASCADE SEQUENCES INITIATED BY RHODIUM-CATALYZED CYCLOPROPANATION

12.5 ENANTIOSELECTIVE CYCLOPROPENATION

12.6 C–H FUNCTIONALIZATION BY CARBENOID-INDUCED C–H INSERTION

12.7 COMBINED C–H ACTIVATION/COPE REARRANGEMENT(CHCR)

12.8 FORMATION AND REACTIONS OF RHODIUM-BOUND YLIDES

12.9 VINYLOGOUS REACTIONS OF RHODIUM–VINYLCARBENOIDS

12.10 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

13 RUTHENIUM CARBENES

13.1 INTRODUCTION

13.2 IMPROVED MECHANISTIC UNDERSTANDING

13.3 CATALYST DEVELOPMENT

13.4 ACHIEVING SELECTIVITY IN ALKENE METATHESIS

13.5 APPLICATIONS

13.6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

14 NUCLEOPHILIC CARBENES OF THE CHROMIUM TRIAD

14.1 INTRODUCTION

14.2 CHROMIUM CARBENES

14.3 MOLYBDENUM CARBENES

14.4 TUNGSTEN CARBENES

14.5 CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

15 COBALT-MEDIATED CARBENE TRANSFER REACTIONS

15.1 INTRODUCTION

15.2 COBALT-CATALYZED CYCLOPROPANATION REACTIONS

15.3 OTHER COBALT-CATALYZED CARBENE TRANSFER REACTIONS

15.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

16 GOLD CARBENES

16.1 INTRODUCTION

16.2 NATURE OF THE Au–CARBON DOUBLE BOND

16.3 GENERATION AND REACTIONS OF GOLD CARBENES

16.4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

SUGGESTED READING

REFERENCES

SUPPLEMENTAL IMAGES

INDEX

Steven E. Rokita, Series Editor

Quinone Methides

Edited by Steven E. Rokita

Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acid Chemistry

Edited by Marc Greenberg

Carbon-Centered Free Radicals and Radical Cations

Edited by Malcolm D.E. Forbes

Copper-Oxygen Chemistry

Edited by Kenneth D. Karlin and Shinobu Ihoh

Oxidation of Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins: Kinetics and Mechanism

By Virender K. Sharma

Nitrenes and Nitrenium Ions

Edited by Daniel E. Falvey and Anna D. Gudmundsdottir

Contempopary Carbene Chemistry

Edited by Robert A. Moss and Michael P. Doyle

Copyright © 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Moss, Robert A., author.

Contemporary carbene chemistry / Robert A. Moss, Michael P. Doyle.

pages cm. – (Wiley series of reactive intermediates in chemistry and biology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-23795-3 (hardback)

1. Carbenes (Methylene compounds) 2. Carbon compounds. I. Doyle, Michael P., author. II. Title.

QD305.H5M67 2014

547′.01–dc23

2013023529

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Most stable compounds and functional groups have benefited from numerous monographs and series devoted to their unique chemistry, and most biological materials and processes have received similar attention. Chemical and biological mechanisms have also been the subject of individual reviews and compilations. When reactive intermediates are given center stage, presentations often focus on the details and approaches of one discipline despite their common prominence in the primary literature of physical, theoretical, organic, inorganic, and biological disciplines. The Wiley Series on Reactive Intermediates in Chemistry and Biology is designed to supply a complementary perspective from current publications by focusing each volume on a specific reactive intermediate or target and endowing it with the broadest possible context and outlook. Individual volumes may serve to supplement an advanced course, sustain a special topics course, and provide a ready resource for the research community. Readers should feel equally reassured by reviews in their specialty, inspired by helpful updates in allied areas, and intrigued by topics not yet familiar.

This series revels in the diversity of its perspectives and expertise. Where some books draw strength from their focused details, this series draws strength from the breadth of its presentations. The goal is to illustrate the widest possible range of literature that covers the subject of each volume. When appropriate, topics may span theoretical approaches for predicting reactivity, physical methods of analysis, strategies for generating intermediates, utility for chemical synthesis, applications in biochemistry and medicine, impact on the environment, occurrence in biology, and more. Experimental systems used to explore these topics may be equally broad and range from simple models to complex arrays and mixtures such as those found in the final frontiers of cells, organisms, earth, and space.

Advances in chemistry and biology gain from a mutual synergy. As new methods are developed for one field, they are often rapidly adapted for application in the other. Biological transformations and pathways often inspire analogous development of new procedures in chemical synthesis, and likewise, chemical characterization and identification of transient intermediates often provide the foundation for understanding the biosynthesis and reactivity of many new biological materials. While individual chapters may draw from a single expertise, the range of contributions contained within each volume should collectively offer readers with a multidisciplinary analysis and exposure to the full range of activities in the field. As this series grows, individualized compilations may also be created through electronic access to highlight a particular approach or application across many volumes that, together, cover a variety of different reactive intermediates.

Interest in starting this series came easily, but the creation of each volume of this series required vision, hard work, enthusiasm, and persistence. I thank all of the contributors and editors who graciously accepted the challenge.

STEVEN E. ROKITA

John Hopkins University

The origins of modern carbene chemistry can be found in Jack Hine’s incisive mechanistic studies of chloroform hydrolysis, which implicated dichlorocarbene (or “carbon dichloride,” as Hine termed it) as the key intermediate. Published in 1950, Hine’s work initiated a myriad of studies, which shows no sign of abating even after 60 years.

Along with the continuing stream of primary research reports, pertinent monographs have appeared regularly, summarizing progress and solidifying our increasing understanding of the physical organic chemistry and synthetic potential of divalent carbon compounds. It is instructive to examine the contents and foci of the earliest texts, not only to chart the developmental history of carbene chemistry, but also to trace the temporal succession and evolution of those problems that have been of central concern.

Hine’s Divalent Carbon (1964) focused on the formation and reactions of key carbene types, e.g., methylene, halocarbenes, and alkoxycarbenes. The formation of methylene and its derivatives from diazo compounds and ketenes was also reviewed. Significantly, Hine recognized isonitriles as “double-bonded divalent carbon,” relatives of today’s stable carbenes. Kirmse’s Carbene Chemistry (1964) adopted a functional group approach to carbene structure, considering methylene, alkyl- and arylcarbenes, as well as carboalkoxy-, alkoxy-, amino-, halo-, and ketocarbenes. Importantly, Gaspar and Hammond’s now-classic chapter on carbene spin states was included. A second edition of Carbene Chemistry (1971) added chapters on structure and reactivity, structural theory, spectroscopy, carbene analogs, and reaction types. The two volumes of Carbenes by Jones and Moss (1973, 1975) featured essays on carbenes from diazo compounds, carbene–alkene addition reactions, reactions of carbon atoms and unsaturated carbenes, organometallic carbene precursors, physical methods applied to carbenes in solution, and an updated version of Gaspar and Hammond’s spin state chapter. Carbene (Carbenoide), a landmark, multiauthored, two-volume set edited by Manfred Regitz (1989), summarized in exceptional depth, scope, and detail nearly 40 years of modern divalent carbon chemistry. Finally, Advances in Carbene Chemistry, a three volume set edited by Udo Brinker (1994, 1998, 2001), exemplified the breadth and depth of twentieth century carbene chemistry, while Carbene Chemistry: From Fleeting Intermediates to Powerful Reagents, edited by Guy Bertrand (2002), heralded the new country’s focus on selectivity.

Now, some 10 years later, carbene chemistry has experienced a remarkable renaissance, entering a new era, driven by advances in spectroscopy—especially fast and ultrafast laser flash photolysis, continuing progress in theory and computational methodology, and signal developments in synthetic chemistry. The latter feature an ever-expanding arsenal of stable carbenes and metal carbenes, useful both as catalysts and as reagents. Spectroscopy now allows the visualization of transient carbenes, together with their excited state precursors, on the nanosecond to femtosecond time scales, while theory enables increasingly accurate calculation of the carbenes’ energies and spectra, as well as many features of the energy surfaces upon which their reactions occur. Additionally, developments in reaction dynamics help to characterize the optimum reaction channels for transient carbenes generated on relatively flat energy surfaces.

At the same time, carbene chemistry now provides widely used, highly selective synthetic methodologies that were only nascent 20 years ago. Chemical transformations of carbenes, including metathesis and carbon–hydrogen insertion reactions, have claimed their place in the synthetic chemistry lexicon, controlling carbene reactivity via transition metal-bound intermediates. Moreover, the role of carbenes in these catalytic processes is well-understood in both mechanistic and synthetic terms. From “unselective” as a characteristic description in the 1960s, carbenes, tamed by association with transition metals, are now paragons of catalytic selectivity, while stable carbenes themselves are important catalysts and ligands in an ever-widening spectrum of reactions.

Contemporary Carbene Chemistry focuses on the most innovative and promising aspects of carbene research over the past decade. We do not dwell on those classical mechanistic concerns, which, for the most part, are now resolved. Rather, we explore newer structural, catalytic, and organometallic aspects of carbene chemistry, with a particular emphasis on synthetic applications. The essays that follow are not intended to be exhaustive reviews. Instead, they highlight the most interesting, fruitful, and promising initiatives in their topical areas. In Part 1, Properties and Reactions of Carbenes, we consider new paradigms of carbene stability, acid–base behavior, and catalysis. Aspects of carbenic structure and reactivity are highlighted by chapters on stable carbenes, carbodicarbenes, carbenes as guests in supramolecular hosts, tunneling in the reactions of carbenes and oxacarbenes, and the ultrafast kinetics of carbenes and their excited state precursors. Theoretical concerns are explored in chapters on computational methods, and dynamics applied to the reactions of carbenes. In Part 2, Metal Carbenes, our attention turns to the synthetic dimension, particularly the reactions and catalytic properties of metal carbenes. The metals considered include, lithium, rhodium, ruthenium, chromium, molybdenum, tungsten, cobalt, and gold. In addition, each chapter features a concluding section summarizing the current situation, highlighting near-term problems, and pointing to likely research directions. A list of key reviews and suggestions for further reading also accompanies each chapter.

Any book that bears “contemporary” in its title challenges the future. We welcome this challenge. If Contemporary Carbene Chemistry aids the research that renders it redundant, then it will have served its purpose; its authors and editors will be more than content.

New Brunswick

College Park

MICHAEL P. DOYLE

ROBERT A. MOSS

Christopher W. Bielawski*, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Jeffrey W. Bode*, Laboratorium fur Organische Chemie, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Udo H. Brinker*, Department of Chemistry, Institute of Organic Chemistry, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; Department of Chemistry, The State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, USA

Gotard Burdzinski*, Quantum Electronics Laboratory, Faculty of Physics, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland

Vito Capriati*, Dipartimento di Farmacia, Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro,” Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale Metodologie e Processi Innovativi di Sintesi, Bari, Italy

Xin Cui, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Huw M. L. Davies*, Department of Chemistry, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Steven T. Diver*, Department of Chemistry, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Amherst, NY, USA

Jonathan M. French, Department of Chemistry, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Amherst, NY, USA

Gernot Frenking*, Fachbereich Chemie, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Dennis Gerbig, Institute of Organic Chemistry, Justus-Liebig University, Giessen, Germany

Scott Gronert*, Department of Chemistry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

Christopher M. Hadad*, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

K. N. Houk*, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

James R. Keeffe, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA

Hoi Ling Luk, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Jessada Mahatthananchai, Laboratorium fur Organische Chemie, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Richard S. Massey, Department of Chemistry, Durham University, Durham, UK

Dina C. Merrer*, Department of Chemistry, Barnard College, New York, NY, USA

Jean-Luc Mieusset, Department of Chemistry, Institute of Organic Chemistry, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Jonathan P. Moerdyk, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Rory A. More O’Ferrall*, School of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

AnnMarie C. O’Donoghue*, Department of Chemistry, Durham University, Durham, UK

Brendan T. Parr, Department of Chemistry, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Mathew S. Platz*, Department of Chemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Murray G. Rosenberg, Department of Chemistry, The State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, USA

Peter R. Schreiner*, Institute of Organic Chemistry, Justus-Liebig University, Giessen, Germany

Ralf Tonner, Fachbereich Chemie, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Zachary J. Tonzetich*, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA

Shubham Vyas, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Lai Xu, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA

Liming Zhang*, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

X. Peter Zhang*, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

*Denotes lead author.

Assessing the stabilities of carbenes has been a richly rewarding, but frustrating endeavor in organic chemistry over the past several decades.1–9 The investigations have required heroic efforts in the synthesis of precursors, validation of carbene formation, and extraction of thermodynamic parameters. The field is studded with examples of elegant and sophisticated approaches to avoid the complications presented by these often highly reactive intermediates. The pursuit of some carbenes has been so extensive, controversial, and fraught with difficulty, that it offers material possibly better suited for a novel than a scientific review. In this chapter, space limitations do not allow for a full historical review and accounting of all the major contributions that have been made in the study of carbene stability. The review will focus on the latest or most accurate values that are available for selected species of fundamental interest (multiple values will be given if a consensus value is not available). As a result, some classical and seminal work may not be directly referenced in this chapter, but instead be found in the cited references. We will begin with a brief discussion of strategies for assessing carbene stability, and the experimental and computational methods that have been used, and then move directly to the stabilities of various classes of carbenes.

Although stability is a familiar concept in all of organic chemistry, describing it precisely can be problematic in practical applications because appropriate, universal reference states cannot always be defined. In some cases, such as carbanions, a single reaction process, protonation in this case, provides a stability measure, proton affinity (PA), which has been broadly embraced by the organic chemistry community. For carbocations, hydride affinities have also been widely used to characterize stability. This has not been true for carbenes, in part because they have varied reaction patterns, but also because they have not been amenable to some physical measurements. As a result, carbene stability has been described in a number of ways, including singlet–triplet energy gaps, reaction energetics such as hydrogenation energies, and kinetic reactivity. Each of these approaches probes a somewhat different aspect of carbene stability and generally correlates with a different reference state. In this chapter, the goal will be to provide a broad overview of these measures of stability, along with a very detailed analysis of the stability of fundamental species on the basis of computed hydrogenation energies.

When choosing a reference state for judging carbene stability, there are generally two considerations that drive the decision process. In the first approach, the decision is driven by a chemical process of interest. This is usually straightforward and can be determined on the basis of relative reaction energies or kinetics. However, this approach is specific to the process and may or may not answer the question of stability in the most general sense. For example, the singlet–triplet gap is a well-defined measure of the relative stability of electronic states of carbenes and offers insight into their spectral properties, but it has only indirect relevance to the ease of formation or the bond-forming reactivity of the carbene.

The second approach is to define a universal reference state that offers no strain or special stabilization. Heats of formation are a simple example of this approach, but they offer limited utility for comparative work because they scale with the molecular formula and therefore direct comparisons are only valid with isomers. A more practical application of this strategy is to relate stability to a model that lacks any of the strain or stabilization that is being probed in the target. These approaches often refer back to alkyl groups and/or employ isodesmic/homodesmotic reactions to extract the stabilization or strain energies.

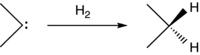

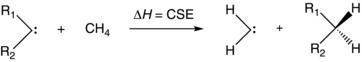

In this chapter, we will focus on two measures of carbene stability. The primary measure will be hydrogenation energies for the conversion of the carbene center to a tetravalent carbon (Eq. 1.1). The motivations for this choice are: (i) the conversion generally eliminates special orbital interactions that potentially stabilize or destabilize the carbene; (ii) stabilization of singlet and triplet carbenes can be determined separately; and (iii) the reference states are often stable species with well-established thermochemistry.10

(1.1)

To conveniently express these stabilizations as relative values, Equation (1.1) can be recast as a homodesmotic process with methylene as the standard reference (Eq. 1.2).

(1.2)

Here, the carbene stabilization energy (CSE) is defined as the enthalpy of Equation (1.2) and can be calculated with the carbene species in either the singlet or triplet state (although the product is taken as a singlet so that the reaction violates spin conservation for the triplet). By this definition, a positive CSE value indicates that the substituent provides greater stabilization to the carbene than a hydrogen. This general approach has been taken in the past to assess carbene stability. In 1980, Rondan et al. introduced a similar term based on computed data, referred to as ∆Estab, which gave good correlations with measures of carbene reactivity.10a Boehme and Frenking also employed a similar approach when assessing carbene, silylene, and germylene stability with computed data.10b

Although CSE values offer insight into both singlet and triplet stabilizations, they do not directly reveal the singlet–triplet gap, ∆EST, because the former is an ensemble rather than a molecular term. For that reason, we will report both ∆EST and CSE values in cases where both are available. Some kinetic data will also be presented to construct correlations between carbene stability and kinetic reactivity.

Finally, the chapter will present extensive computational data along with the experimental data. The rationale for this approach is that experimental data for carbene stability are still far from comprehensive, are derived from experiments in a variety of media, and often suffer from significant uncertainties in the data needed to satisfy Equations (1.1) and (1.2). Computational values, despite their inherent and indefinable uncertainties, allow for the construction of structure/stability relationships that offer powerful qualitative, if not quantitative, insights into the structural features that modulate the stabilities of singlet and triplet carbenes.

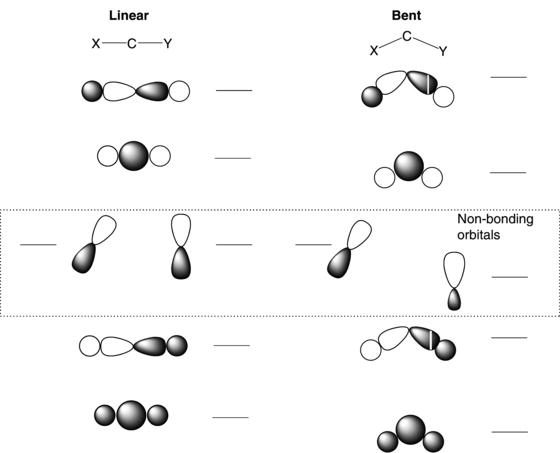

In following chapters, many aspects of carbene structure and reactivity will be explored. Therefore, only a brief overview of critical orbital interactions will be provided here as a foundation for explaining trends in carbene stability. A logical place to begin is to examine the valence orbitals of a carbene in a linear or a bent geometry. The contrast between them gives insight into factors that will control the preferences for singlet and triplet ground states. Qualitative orbital diagrams for a linear and a bent carbene are given in Figure 1.1. The bending leads to rehybridization and a number of effects on several molecular orbitals, but the key changes are in the p-orbitals that are nonbonding in the linear geometry (dashed box). The degeneracy in these orbitals is broken when a bend is introduced and the energy gap between the pure p-orbital and the one that is rehybridizing (moving towards sp2-like) grows as the angle at the carbene center is contracted. The carbene carbon has six valence electrons and four will occupy the two, low-energy sigma-bonding orbitals. The remaining two electrons are then distributed into one or both of the orbitals shown as nonbonding in Figure 1.1. In the linear geometry one expects, by analogy to Hund’s Rule, that the electrons will occupy each of the degenerate orbitals with a preference for a triplet ground state. In the bent geometry, the situation is not so clear because the gap in energy between the two nonbonding orbitals may be sufficient to overcome the spin-pairing energy and a singlet can become the preferred ground state.

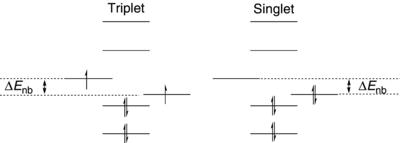

The orbital occupancies for a triplet and a singlet in a bent geometry are outlined in Figure 1.2. The ∆Enb is the important energy term and as noted earlier, it is expected to increase as the angle at the carbenic carbon is reduced. So far, orbital interactions with the X and Y groups on the carbene center (Fig. 1.1) have been ignored. Clearly, these groups can alter ∆Enb by stabilizing or destabilizing the operative orbitals. Much of the discussion in this chapter will focus on the orbital interactions of the groups attached to the carbene center.

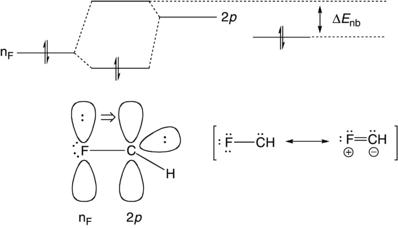

Before discussing specific cases in the following sections, it is useful to consider generalizations about factors that affect the preferences for singlet versus triplet ground states. As a starting point, CH 2 (X,Y = H), is a ground-state triplet with a 9 kcal/mol gap between the lowest triplet and singlet states. 11 Consequently, carbene substituents must provide at least 9 kcal/mol of preferential stabilization to the singlet to tip the balance to a singlet ground state. Although it is a crude model, one can view a singlet carbene as possessing the key characteristics of both a carbocation and a carbanion, namely, an empty p-orbital and a carbon-centered lone pair. Therefore, X and Y groups that provide orbital interactions that can stabilize a carbocation or carbanion, relative to a radical (the key feature of the triplet orbital occupancy), could potentially stabilize the singlet state. It is well-known that substituent effects are considerably larger for carbocations than carbanions and the stabilization of singlet carbenes by substituents generally parallels trends found for carbocations. With that in mind, the most obvious stabilizing interaction for a singlet carbene would be electron donation to the unoccupied, nonbonding orbital by either conjugation with a lone pair/π-bond or hyperconjugation to a saturated carbon. The situation is illustrated for a fluoro-substituted carbene in Figure 1.3. Interaction of the fluorine lone pair with the unoccupied 2p orbital on the carbene stabilizes the overall singlet system by reducing the nF orbital energy, but the unoccupied molecular orbital is shifted by this interaction to a higher energy than the starting 2p orbital, causing a net increase in ΔEnb which, in turn, disfavors the triplet state. In fact, the singlet of FCH is favored by 15 kcal/mol over the triplet,12 a net shift of 24 kcal/mol in the singlet–triplet gap relative to unsubstituted CH2. The valence bonding from these orbital interactions can be illustrated by the introduction of an ylide resonance form. The contribution of the ylide resonance depends on the nature of the substituents and when it dominates, the carbene is expected to behave like an ylide and display little of the reactivity that is typically seen in singlet carbenes (i.e., insertion reactions and dimerizations).

Figure 1.1. Molecular orbitals for linear and bent carbenes.

Figure 1.2. Orbital occupancies for triplet and singlet carbenes.

Figure 1.3. Interaction of a fluorine lone pair with a carbene.

In summary, molecular orbital considerations suggest two general factors that should modulate preferences for singlets and triplets. (i) Larger X–C–Y angles will favor the triplet by reducing the hybridization difference and therefore the energy gap between the nonbonding orbitals. (ii) Electron-donating groups favor the singlet by raising the energy of carbene’s pure 2p orbital. These factors will be discussed in more detail in the sections that follow. Finally, the analogy to carbocations suggests that singlet carbenes can gain significant stabilization via conjugative interactions, possibly diminishing or eliminating their characteristic carbene reactivity.

Experimental measures of carbene stability offer several challenges. In many simple examples, such alkyl carbenes, the barrier to rearrangements, often to alkenes via a 1,2 hydrogen shift, may be negligible and therefore carbene lifetimes can be too short for direct analysis even in an inert environment (however, they may be probed via spectroscopy on their corresponding radical anions, see section 1.2.3.1 “Anionic Photoelectron Spectroscopy”). For these short-lived carbenes, the options for characterizing their stability are generally limited to fast kinetic methods or computational modeling. For species that are stable in inert environments or have significant lifetimes, there are other experimental techniques that can provide quantitative stability data. In some cases, such as N-heterocylic carbenes, the carbene is indefinitely stable and its properties can be probed by conventional approaches such as pKa determinations (see section “Other Experimental Measures of Stability” under Section 1.3.4.4). Here, brief descriptions are provided for three approaches that are applicable to the study of relatively reactive carbenes.

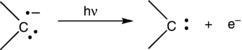

The most accurate method for determining singlet–triplet gaps has been anionic photoelectron spectroscopy.13 In this technique, a radical anion precursor to the carbene is formed, thermalized in the gas phase, and then subjected to electron detachment via a laser pulse (Eq. 1.3). The kinetic energy distribution of the resulting electron provides information about the electron-binding energies of the singlet and triplet carbene electronic states, as well as their vibrational states. If thresholds for electron detachment to the singlet and triplet states of the resulting carbene can be identified, the singlet–triplet gap can be determined. Although the spectra can be challenging to assign in some cases, and can be complicated by the presence of vibrational “hot” bands in the precursor ion, the data are capable of providing exceptionally accurate singlet–triplet gaps. This technique has provided the singlet–triplet gap for the prototypical carbene, CH2. Although powerful, the technique has several limitations. First, there must be a convenient source for producing the carbanion in the gas phase in its vibrational ground state. The electron-binding energy must be within a range that is accessible by common lasers, and the Franck–Condon factors must allow for a confident assignment of the thresholds for detachment to the singlet and triplet. These conditions are met for a number of small, fundamental systems, and data from anionic photoelectron spectroscopy are presented in Table 1.1 and Table 1.3 in the following sections.

(1.3)

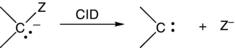

Carbenes can be formed in the gas phase via the fragmentation of an anionic precursor. One approach has been the fragmentation of an α-halo anion via collision-induced dissociation (CID) to produce a halide anion and a carbene (Eq. 1.4).14 If the heat of formation of the starting anion is known (via its proton affinity and the heat of formation of its conjugate acid), the threshold dissociation energy can be used to calculate the heat of formation of the resulting carbene. Like anionic photoelectron spectroscopy, the technique is limited to ions that can be formed and thermalized. However, it lacks the accuracy of anionic photoelectron spectroscopy because it does not generally offer resolution at the vibrational level, and therefore dissociation measurements rely on difficult estimates of the threshold as well as corrections for kinetic shifts in the threshold. Moreover, the data are only for the electronic state in which the carbene is formed, which is generally assumed to be the ground state.

(1.4)

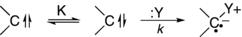

Typically, kinetic measures of reactivity only provide qualitative information about carbene thermodynamic stability.15 Of course, they provide direct measures of kinetic stability with respect to the particular process that is being studied. Some kinetic studies of stability will be summarized later in this chapter. In cases where singlet and triplet states are in rapid equilibrium, addition rates have been used, in conjunction with a number of assumptions, to estimate the equilibrium constant between the singlet and triplet state in solution (Eq. 1.5). The working principle is that only the singlet will undergo the reaction to produce the ylide. This method has been successfully applied in a limited number of cases including phenylcarbene.16

(1.5)

Given the instability of many carbenes, as well as their high reactivity, computational modeling has been used extensively in efforts to assess carbene stability. However, carbenes present special challenges to computational methods. First, the species needed to assess the stability have very different electronic properties. The singlet carbene possesses a lone pair and an unoccupied p-orbital, the triplet has two unpaired electrons, and the reference compounds are often simple, closed-shell species. Therefore, the chosen computational method must handle all of these situations equally well, whereas the advantageous cancellation of errors that often occurs when similar species are compared computationally is much less likely when addressing carbene stability. Second, the electronic states of carbenes can be close in energy and mixing is possible. Finally, even the assumption that electrons are paired in the singlet is not universally valid (singlet diradicals are possible).

There are three general computational approaches that have been routinely applied to carbenes. Traditional ab initio methods with varying levels of electron correlation have been widely used. The second approach is an extension of the first and involves incorporating multiconfiguration wave functions to deal with the mixing of electronic structures. The third is density functional theory (DFT), where a number of functionals are employed including the very popular B3LYP functional. It is safe to say that none of these approaches has been universally accurate and applicable to carbene systems, though very accurate results have been obtained in many cases. Nonethleless, many methods, including B3LYP, cannot accurately characterize the singlet–triplet gap in CH2 without empirical corrections. For example, the computed singlet–triplet gaps for CH2 are 12.2 kcal/mol at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level,17 12.5 kcal/mol at the RCCSD(T)/6-311G(d,p) level,17 9.4 kcal/mol at the G3MP2 level,18 12.1 kcal/mol at the CASSCF(8,8)/6-311++G(d,p) level,17 and 11.6 kcal/mol at the MRCI + Q(6,6)6-311++G(d,p) level.17 The experimental value is 9.0 kcal/mol.11 The computational demands of these methods vary greatly. Multireference approaches incorporating extensive electron correlation are difficult to extend to moderate-sized carbene systems, whereas DFT calculations on smaller systems can be completed in a few minutes on a personal computer. In this chapter, the main computational data will be from a previous study involving the G3MP2 composite method.18 This approach should have good general accuracy in systems where a single configuration is adequate. Some data from other computational methods are also included for comparison.

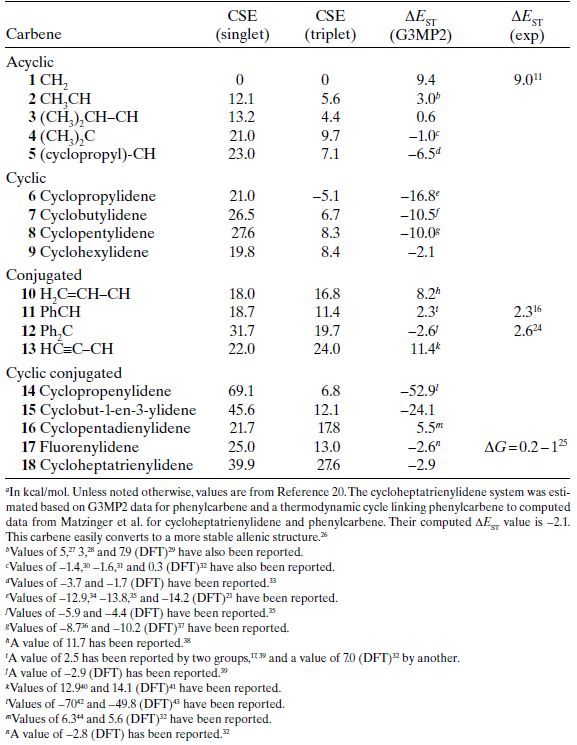

In Table 1.1, data are given for representative cyclic and acyclic alkyl-substituted carbenes. In the footnotes to Table 1.1, a sampling of the many other computed values for carbene ΔEST are listed. As noted earlier, a positive CSE value indicates that the substituent provides greater stabilization to the carbene than hydrogen. A quick survey of Table 1.1 reveals that CSE is positive for all of the singlets—this is not surprising because with the structural duality of an unoccupied p-orbital and a lone pair, electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups have means of stabilizing the singlet carbene. A clear, simple trend is seen in the CSE(singlet) values for the acyclic carbenes, 1–4. Each additional alkyl group at the carbene center provides about 10 kcal/mol of stabilization relative to the hydrogen substituents in CH2. A convenient explanation is that the alkyl groups act as electron-donors via hyperconjugation to the unoccupied p-orbital on the carbene carbon. The comparison between the methyl (2) and dimethyl (4) systems suggests that the effect is nearly, but not completely additive. The cyclopropyl-substituted system (5) is an interesting case which experiences 10 kcal/mol more stabilization than the analogous isopropyl-substituted system (3). This is consistent with the exalted electron-donating ability that is typically seen for the cyclopropyl substituent. For example, the σp values for cyclopropyl and isopropyl are −0.21 and −0.15, respectively.19

The cyclic carbenes in the table are all analogs of the dimethyl-substituted carbene (4). For the four- and five-membered rings, the CSE(singlet) values are reasonably close to that of the acyclic analog, but somewhat higher. In interpreting this result, one must also take into account the reference states that are used in calculating the CSE values, namely the hydrogenation products. For the three-membered to five membered rings, the hydrogenation products are strained and, therefore, the CSE values also contain the changes in strain that accompany hydrogenation. For the four- and five-membered rings, issues with the reference compounds do not appear to be important because there is nothing unusual in the CSE(triplet) values for these species, which share the same reference (see in the following). A likely explanation is that the four- and five-membered ring carbenes benefit from conformational effects that enhance hyperconjugation relative to acyclic systems, and thus a small increase in CSE(singlet) is found. This effect is not seen in the three-membered ring where the CSE(singlet) value is similar to that of dimethylcarbene; however, there is more to this system. The enhanced s-character in the carbene lone pair of the three-membered ring should offer some stabilization (it is the factor that enhances the acidity of cyclopropanes), but this must be balanced by the disadvantages of introducing an unoccupied p-orbital into a three-membered ring (cyclopropyl cations have unusually high hydride affinities)20—the net effect is a CSE(singlet) value near that of dimethylcarbene. As expected, the six-membered ring system gives a hydrogenation product without strain and the CSE(singlet) value is similar to the dimethylcarbene. Not surprisingly, an unsaturated substituent can provide more stabilization to a carbene center than a simple alkyl group. Both vinyl and phenyl substituents provide an extra 6 kcal/mol of stabilization to the singlet relative to a methyl group. The effect appears to be additive and singlet diphenylcarbene (12) experiences 10 kcal/mol of added stabilization relative to dimethylcarbene.

TABLE 1.1. Computed CSE Values, and Computed and Experimental Singlet–Triplet Gaps for Hydrocarbon-Substituted Carbenesa

The final entries in Table 1.1 are a group of cyclic, conjugated carbenes. These are fascinating species because aromaticity can play important roles in the stabilities of singlet states. In these systems, the singlet carbene could fundamentally complete the π-system of the ring either through its unoccupied p-orbital or its lone pair. The smallest in the series is cyclopropenylidene. This species can form a two-electron aromatic π-system if the carbene completes the π-system with its unoccupied p-orbital and aligns its lone pair in the plane of the ring. It can be viewed as the deprotonation product of the highly stable cyclopropenylium cation. The CSE(singlet) value for cyclopropenylidene is extremely large for a hydrocarbon system, 69.1 kcal/mol, giving it a value that is over 50 kcal/mol greater than the stabilization from a simple vinyl group. Aromaticity in cyclopropenylidene is also supported by its calculated nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS). This is a common theoretical approach to evaluating ring current effects and aromaticity. A negative value is associated with aromaticity. Cyclopropenylidene has an NICS value of −16.8.21 As a reference point, the cyclopentadienyl anion has an NICS of −14.3.22 Although aromaticity must play a role in the large CSE(singlet) for cyclopropenylidene, it is insufficient to explain a stabilization of this magnitude. The other factor to consider is the carbene lone pair. In cyclopropenylidene, it benefits from the three-membered ring structure, which increases the s-character in the lone pair orbital and enhances the effective electronegativity of the orbital. The combination of these effects, aromaticity and high s-character in the carbene’s lone pair, combine to provide the observed stabilization of the singlet carbene.

Cyclobut-1-en-3-ylidene (15) has a much larger CSE(singlet) value than vinylcarbene, but not as large as cyclopropenylidene. This system can potentially benefit from homoaromaticity via a cross ring interaction, which appears to be the case given the exalted CSE(singlet) value. With the next largest carbene in this series, cyclopentadienylidene, the electron need of the cyclic π-system is reversed—to form an aromatic π-system, the carbene must donate two electrons to it. Here, the CSE(singlet) value is only 21.7 kcal/mol, a value that is only about 4 kcal/mol greater than that of vinylcarbene. Clearly, singlet cyclopentadienylidene does not experience any special stabilization and, in fact, the cyclic structure appears to reduce the stabilization by the π-system. Computational modeling, including NICS analysis,23 confirms that cyclopentadienylidene does not possess an aromatic π-system; the carbene completes the π-system with its unoccupied p-orbital, leading to an antiaromatic π-system. This electronic structure can be rationalized by considering the cost of completing the π-system with the lone pair. It would require the carbene to have an unoccupied sp2-hybrid orbital in the plane of the ring, which is energetically very unfavorable (analogous to a vinylic cation) and apparently outweighs the benefits of an aromatic π-system.

Fluorenylidene (17) provides a closely related π framework, but its more extended π-system adds only marginal stability to the singlet and a CSE(singlet) value of 25 kcal/mol is obtained. Comparison of this value with the one obtained for diphenylcarbene gives insight into the impact of antiaromaticity in fluorenylidene. By forming the five-membered ring (fluorenylidene can be viewed as diphenylcarbene bridged through the ortho carbons), the CSE(singlet) drops by nearly 7 kcal/mol. Although a number of other factors are at play, this simple comparison highlights the fact that cyclopentadienyl-based carbenes suffer destabilization in the singlet state due to antiaromaticity in their π-systems.

The last entry in Table 1.1 is cycloheptatrienylidene (18). Like cyclopropenylidene, this carbene can form an aromatic π-system by incorporating its unoccupied orbital in the π-system. In this case, a six-electron, aromatic π-system results and cycloheptatrienylidene has a CSE(singlet) value of 39.9 kcal/mol. Although not as exceptional as that of cyclopropenylidene, this CSE(singlet) is unusually large and significantly exceeds that of diphenylcarbene. Of course in cycloheptatrienylidene, the lone pair does not have the benefit of occupying an orbital with exalted s-character, a key feature in stabilizing singlet cyclopropenylidene.

The CSE(triplet) values are much smaller in magnitude and the variation in the acyclic systems is limited. This is not surprising given that the magnitude of hyperconjugative stabilization possible for interactions with a singly occupied orbital is modest at best. Analogies could be made to alkyl-substituted radicals, where alkyl substituents reduce C–H bond strengths by only a few kcal/mol (currently, the magnitude of hyperconjucative stabilization in radicals is a controversial topic45–51). The only system that stands out is the cyclopropylidene system (6), where CSE(triplet) is negative, indicating that this triplet is less stable than CH2