Published by

MOSAÏQUE PRESS

Registered office:

70 Priory Road

Kenilworth, Warwickshire

CV8 1LQ

www.mosaïquepress.co.uk

Copyright © 2010 Bill Larkworthy

The right of Bill Larkworthy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publisher.

Printed in the UK.

ISBN 978-1-906852-07-8

To Maria,

my source of strength in hard times

and love and happiness at all times.

Ah, fill the cup, what boots it to repeat

How time is slipping underneath our feet

Unborn tomorrow, and dead yesterday,

Why fret about them if today be sweet!

– THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM

EDWARD FITZGERALD (TRANS.)

Contents

Introduction

Part One –

‘Per ardua ad astra’

Part Two –

The ‘magical’ kingdom: Saudi Arabia

Part Three –

Dubai: my pearl in the Gulf

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Cover photo: Maria Larkworthy.

Introduction

ONE BITTERLY COLD WINTER FORTY-FIVE years ago, I found myself marooned on a nuclear bomber station on the wind-swept plains of Northern Germany, a junior doctor in the Royal Air Force.

Christmas celebrations were in full swing and, as the lowest ranking medical officer, I had been handed the short straw and was on call for the festive season. This didn’t prevent me from partaking of a large turkey dinner, nor from dozing contentedly afterwards. And sure as a glass of port follows a good meal, the inevitable happened. I was summoned by an urgent call.

“Come quickly, sir, there’s been a suicide, there’s blood everywhere.”

I dashed and skidded over the icy paths to sick quarters and forced my way through a knot of airmen who crowded the entrance, chattering excitedly. A trail of blood led me to the victim who was in the operating theatre being cleaned by a couple of orderlies; surprisingly, in view of the generous quantity of blood splashed about, no source of bleeding could immediately be found.

Clearly the ‘suicide’, a mop-headed corporal named O’Malley, could neither see nor walk a straight line and though practically legless, grinned lopsidedly around the room, not unhappy to be the centre of attention.

We asked one of his mates what had happened. It seemed O’Malley had been drinking solidly in the Corporals’ Club since Christmas Eve, became maudlin on Christmas Day, pulled out a penknife on Christmas afternoon, declared he was going to end it all and set to work cutting off his thumb. Sure enough, eventually we found a ragged incision on the back of his left thumb. Drunks can bleed profusely but even so, this was barely credible.

“What on earth have you been up to, corporal?” I demanded.

His brow furrowed as he attempted to concentrate and get a fix on my position with wobbly, bleary, bloodshot eyes. He paused, hiccuped, took a deep breath and in an Irish brogue slurred, “I was depressed, sor, I wanted to kill myself.”

In my supercilious, know-it-all young flight lieutenant doctor’s voice I exclaimed, “But corporal, you don’t commit suicide by cutting off your thumb!”

After a moment’s reflection he replied, “Ah well you see, sor, I don’t have the benefits of a medical education.”

THAT WAS A LONG TIME AGO, BUT THE STORY has stuck in my mind and led me at times to reflect on the benefits I’ve had from my medical education. For someone like me from modest origins, the benefits have been many: a fascinating career, a passport to all walks of life, to immense job satisfaction, to friendship and to an adequate income. Not least, because I qualified in 1957, I have witnessed, and participated in, the miraculous developments of the past half-century in medical science and life in general.

‘Doctoring’, as I thought of it when I was young, has taken me to many far-flung parts of the globe that I might not otherwise have visited. Many of them - Malaysia, Cyprus, Germany, the Persian Gulf – I recall with a fondness bordering on tearful nostalgia while just as many others – Aden, Bangkok, Moose Jaw – have thankfully faded in my memory like a snapshot left too long in the sun.

Much of that travel was courtesy of the RAF, both by way of overseas postings and the journeys necessitated by the work I was sent there to do. Sometimes it was comfortable, like the mammoth tour of RAF bases between London and Hong Kong by de Havilland Comet. Sometimes it was… less comfortable. Observing terra firma above your head from the seat of a Mirage fighter jet while flying upside-down is, in my experience, a sure way to nausea.

At least that was a seat and a means of emergency egress, should the need arise. I was singularly unimpressed when I learned that my space in a Canberra bomber – actually a face-to-the-tarmac couchette in the nose of the beast – did not come with the luxury of a parachute. “Well Bill,” said my ever-helpful flight crew, “where you are, it will be impossible to get out.” On such occasions, I had to remind myself that I had actually volunteered to go along for the ride.

My medical education also introduced me to a cast of characters and plots richer than those of any costume drama or soap. I met the military equivalent of WAGs, the spouses who had to be repatriated because they couldn’t deal with a ‘hardship’ posting in the sun and warmth of Malta, and at the other end of the scale, Gurkha soldiers who knew real hardship and laughed in its face. They were fighting communists, the insurgents du jour, in the jungle of Malaysia. Even in hospital, sick or wounded, these troopers remained highly disciplined: they would snap to attention under the sheets when I approached if they were too ill to get out of bed.

Across my path have strayed various eccentrics, charlatans, buffoons and braggarts; ‘doctors’ who weren’t what they seemed and unsung heroes who most definitely were; a colleague driven to enlist the services of the Russian Mafia and one of Saddam’s ‘human shields’ who lived to drink another bottle of Dom Perignon. There was even a genuine celebrity, the explorer and writer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, who late in his life was a regular visitor to Dubai. One time I fixed his feet with a scalpel. “Perfect,” he told me, “now I’ll be able to take that walk in the desert with Charles.” Yes, that Charles.

Medicine carried me into the most glorious, beautiful desert of the Middle East and across the thresholds of palaces of breathtaking opulence in the ‘magical’ kingdom of Saudi Arabia, to a pinnacle of sorts when I could rightly claim to be ‘physician to HM the King’. He was a pleasant and dignified man who was grateful when the treatment I prescribed was a success, quite unlike the megalomaniac, drug-addled hospital director who had me thrown into prison — the lowest point in my career. That’s when you find out who your friends are, and I’ve been fortunate to have collected some good ones, especially in Riyadh.

True, there are some things a medical education didn’t teach me, like how to fix a leaking car radiator with the contents of a spice shop (think yellow), an antidote to boredom on the Canadian prairies, or how to distinguish between a taxi and a police car on the sinful streets of Patpong… but that’s a story in itself. It did teach me indirectly how to operate a modern fast jet’s ejection seat – a skill, not surprisingly, that I have never had call to demonstrate.

Doctors collect stories as they follow their careers; it’s in the nature of the job. Some are touching, some horrifying, some sad and many quite funny, certainly in retrospect. I was amazed, as I compiled this memoir, at what came flooding into my mind, one memory triggering another and stories appearing seemingly out of nowhere. Tales I thought I had forgotten came forward, sometimes with the startling clarity of an ageing brain and sometimes, I admit, with embellishments of half-remembered events — well, anyway, this is my life, this is how it looked to me — and it’s how I made the most of my medical education.

Bill Larkworthy

Provence, France

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I HAVE TRIED TO BE ACCURATE but I wrote with no records and no notes – any inaccuracies or errors of interpretation are mine and accidental.

Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

BL

The author and his older brother, Leslie, about 1936.

One

I WAS SIX WHEN THE SECOND WORLD WAR broke out, or to be more precise, spread itself over our home in Plymouth like a chill fog off the Channel. I remember the moment as clearly as yesterday. Just after eleven in the morning of 3 September 1939, my family of four silently gathered around the wireless. It was a wooden box with a fretwork face and round knobs that you weren’t supposed to touch; we called it a wireless at the time to acknowledge the miracle of music and voices travelling through the ether, as if by magic, and not down wires like a telephone, which for some reason made more sense to my young mind.

Through the fizz and crackle of static the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, droned on in measured, unemotional tones: “This morning the British ambassador in Berlin handed the German government a final note stating that, unless we heard from them by eleven o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

I didn’t understand what was going on but became fearful, complained of a pain in my stomach and my mother gave me half a teaspoonful of bicarbonate of soda dissolved in water – her sovereign remedy for all symptoms abdominal. Later I asked my brother what it was all about. Leslie was two years older but he didn’t know either.

For us it was both a good time and a bad time. Good, because a nation at war becomes united. There is a sense of facing danger together, of having a common enemy, of ‘mustn’t grumble’, of getting on with others and everybody striving to do their best for the common cause. These qualities became infused into my six-year-old spirit and as the war progressed Nazi and Japanese aggression deepened my patriotism.

A bad time: well, Jerry could drop a bomb on you.

Everybody believed that German planes would be overhead any day. At school we had endless gas mask and bomb shelter drills but it wasn’t until the early summer of 1940 that enemy Messerschmitts, Heinkels and Junkers appeared in numbers in the skies over England.

Most of the air raids were at night. Our house in Seymour Avenue had a cellar and we sheltered there among tins, preserves, old magazines and boxes. If the air-raid sirens started wailing in daylight hours and we were at school, we were quickly ushered into the shelters which had been thrown up in the school yard. When the ‘all clear’ sounded, we would march back to our classrooms singing at the tops of our voices, There’ll always be an England or Rule Britannia – great for morale but when we heard that a shelter in another school in Plymouth had taken a direct hit which killed all fifty children in it, that morale took a serious dip.

The author’s parents, Jack and Esther Emma Larkworthy, on their wedding day in Plymouth, 1928.

The author, his brother and mother at home in ‘Sunday best’, about 1936.

In the next two years, Plymouth suffered the most concentrated bombing of any British city. During the Blitz, the city lost altogether 1,174 lives. I vividly recall on many occasions emerging from our air raid shelter and seeing the sky a deep red from horizon to horizon as Plymouth burned. In one week in 1941, the centre of the city was flattened but the tower of Charles Church was left standing, unscathed, an omen we regarded as showing that the Lord was on our side. Not that we needed reassurance; we had known that from the start.

Like other boys in the city, Leslie and I would collect shrapnel. At the end of air raids, we would beg to be allowed to go for a walk in the nearby streets where we would pick up jagged pieces of metal, some still hot. We became proficient at recognising the noise of German aircraft engines and were able to distinguish their throbbing sound from the continuous note of British aircraft and the joyous singing of the Rolls-Royce Merlin of the Spitfire. It was a matter of some considerable youthful pride to be able to reassure grown-ups and say confidently, “That’s one of ours.”

We were less confident one summer afternoon when we had a close encounter with a Messerschmitt Bf 109. My brother and I were in the country, about five miles from Plymouth wandering along a hot and dusty road, when suddenly there was a roar and the German aircraft flashed before our eyes. ‘The Hun’ was hedge-hopping to escape the RAF. It must have been only a millisecond before he disappeared but in that time the yellow nose cone, yellow wing tips, black and white cross on the fuselage and swastika on the tail all registered. The pilot was gazing down at Leslie and me through hexagonal goggles with a malicious grin on his face. We were sure he would come back to machine-gun us and dived into a ditch where, with Leslie’s protective arm around my shoulder, we crouched for half an hour; thrilled, frightened and excited.

To do her part, my mother joined the Women’s Voluntary Service but with my father it was a different story. He was a registered conscientious objector and as such was an outcast, particularly in a city subjected to so much brutal bombing; a city with proud military and naval traditions. It’s impossible to know how much he suffered at the hands of others. He must have appeared before a tribunal which declared his job – he was an engine driver on the Southern Railway – a reserved occupation and did not imprison him or direct him to other work. While relatives enlisted in the armed forces, he continued to drive trains. Some carried munitions and all were fair game for marauding German aircraft.

My father was a man of strong moral conviction and a stubborn nature. Later the family claimed that I had inherited his stubbornness but I prefer to think of it as dogged determination. His beliefs had no religious basis. He was no coward: he single-handedly extinguished a blazing incendiary bomb and when congratulated, shrugged and walked away. Within the family he was an outsider. I don’t recall specific embarrassments but in my tender years I was segregated from much of what was going on.

Although my father had no professed religious beliefs, the rest of the family was strictly Church of England and practised the lowest Anglicanism. This would have a profound effect on my life and even today, seventy years later, I have pangs of guilt if I catch myself having a good time – well, sometimes anyway.

On Sundays Leslie and I went to church, at least once; games at home were forbidden; in the summer we weren’t allowed to go swimming; we could listen only to the BBC six o’clock news on the wireless and reading was limited to ‘improving’ books. Playing cards (the Devil’s Book) were of course outlawed. I wonder now how we survived.

Our local church was St Judes. The vicar, the Reverend H G McMaking, led a seriously low-brow congregation. Week after week the theme of his sermons was ‘Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die!’ I can see him now as he stood in the pulpit, a tall, well-fed man of God with rosy cheeks and a remarkably thick fringe of white hair surrounding a natural tonsure, thundering that message again and again. Sometimes his credibility was enhanced as, with his white priest’s robes swirling and fist (two fists for added emphasis) raised on high, he was illuminated by a solitary divine ray of sun beaming through a stained glass window. Then he would lean confidentially over the edge of the pulpit and with a gentle smile, drop his voice – and I knew he was talking personally to little open-mouthed, eight-year-old me – “And what? And what if? And what if when you leave this church as you cross the road YOU ARE KNOCKED DOWN BY A BUS AND KILLED?” I sat quaking… he thundered again, “Will you be ready? Will you be prepared to meet YOUR GOD?” Me, prepared? What’s prepared?

In a few years I reached the age for confirmation and I, with a couple of other boys of my age, attended the vicarage once a week for ‘preparation’. Perhaps this was what he was talking about.

But the only clear recollection I now have of all the weeks of tuition of the Rev H G McMaking was that he discussed masturbation with us, telling us what a dreadful sin of the flesh it was and how it could lead to a weak constitution, lassitude, sterility, visual defects, mental deficiency, deafness, madness and early death.

The problem was that none of us knew what he was talking about. We discussed it among ourselves when we left the vicarage and elected one of our number, me, to ask next time.

“Please, sir,” I said at the beginning of the session, “we don’t understand, what’s this master thing you talked about last week?”

His eyes lit, he beamed, he said, “Well boys, it’s like this.” And short of an actual hands-on demonstration, he gave an account easily understood by any pre-pubertal boy. “Ho hum,” I thought, “this sounds fun.” I couldn’t wait to get home and try it out. Nothing happened, my hormonal juices hadn’t yet kicked in… but some months later they did; to my utter, incredulous amazement.

A FEW YEARS LATER I JOINED THE YOUTH club run by the church. My motives were simple: my testosterone had reached boiling point and there were girls there. Admittedly many were pretty plain (they were the religious ones) but there were a few who were the stuff of adolescent male dreams.

At that time a certain American evangelical preacher, Billy Graham, was touring the land and converting sinners by the drove. We had our very own in-house evangelist in the form of a local dentist, David Barley, a young man with tight, curly ginger hair and an ever-present welcoming Christian smile. At each meeting he would put on a lively fire-and-brimstone act and scare the living daylights out of his fearful audience over their sins, some real but most imagined. Mr Barley’s wife played the piano for him. Pamela was her name; she was pretty, petite and a divine inspiration of an entirely different order. How they missed the way we lads would gaze in raptures of feverish imagination at the turn of her ankles, the curve of her derriere on the piano stool and the swaying of her perfect chest as her fingers danced over the keys, I cannot guess.

Before club evenings, at which we played table tennis or billiards while studying the girls, Mr Barley would assemble us spotty adolescents and give us hell for half an hour. Then, following a few fervent prayers and several hallelujahs, we would kneel and pray in silence with our eyes closed. After five minutes he would call for those who had ‘seen the light’ to come forward to be blessed. I would peek between my fingers and each week, to my astonishment, saw everybody go up to him one by one, have him rest his hands on their heads and mutter a blessing. This happened week-in, week-out and week-in, week-out I didn’t go up; obviously I couldn’t… I hadn’t Seen the Light.

At last the ultra-religious dentist stopped me one evening as I was leaving. “Bill,” he said, “we have been discussing your case and we want to know why you haven’t yet seen the light?”

“Well, I’m very sorry but I just haven’t seen any light,” I replied.

He told me what a glorious opportunity I was missing and I promised to try harder – I didn’t go back.

The next time I saw him he was hot gospeling in Union Street (a notoriously sinful part of Plymouth), I was emerging from the Odeon cinema, it was a Sunday and I had been indulging in first class sinning. I had taken myself alone to the cinema where I puffed away on a tuppenny packet of Wills Wild Woodbine cigarettes. As I emerged, he was standing on the opposite side of the road, on a soap box, the pretty Pamela standing next to him with tambourine at the ready and a small crowd around him. Our eyes met, he stared; I smiled, waved to them and walked nonchalantly away.

But divine retribution was waiting around the corner. Soon I was to be overtaken by a calamity of immeasurable proportions. My hair began to fall out in handfuls. By the age of fifteen I had a parting an inch wide. People were noticing, friends looked and smirked. I was acutely embarrassed and full of self-pity… life was over for me; something had to be done.

I saw an advertisement in a paper which guaranteed to cure baldness with a course of tablets; the problem was the cost, two guineas for the course. I worked at odd jobs, I scraped together the money.

The tablets were brown in colour there were enough for three months at one a day. The advertising blurb said impressively that they contained 7-dehydrocholesterol and the promoter guaranteed his probity by declaring that he was an ex-RAF squadron leader Spitfire pilot. Simple me… many years later I came across those very same tablets when doing my midwifery training; they were given routinely to pregnant women, cost virtually nothing and were simply vitamin D tablets. And later still I was to learn that the rank of squadron leader is not synonymous with honesty.

My hair continued to fall out in clumps, I came to accept it and as I looked at the many bald members of my family, more than a few on the female side, it was clear that fate had dealt me a low card. But there were a few advantages. By the time I reached my twenties I was as bald as I am now, five decades later; a bald head, a bow tie and I could pass for a senior registrar while I was still a medical student.

REGARDLESS OF THEIR DIFFERENCES my parents were totally in agreement that for their sons a good education was of the utmost importance. Fortunately early in the war my brother and I passed what was then known as the ‘scholarship’, later to become the 11 Plus, and we entered a good local grammar school, Sutton High.

Leslie was brilliant at school; I was no better than average. He picked up prizes galore; he was even selected to appear in a children’s quiz on the BBC because he was so bright.

Childrens’ Hour was broadcast every afternoon at five and was the first BBC programme to introduce what were destined to become extraordinarily popular quiz shows. The director was ‘Uncle Mac’ (Plymouth born Derek McCulloch) assisted by Violet Carson (later Ena Sharples of Coronation Street) and the competition was between schoolchildren in the different BBC regions.

Leslie did well until the final question posed by the avuncular Uncle Mac. “What do the letters MCC stand for?” Pause. Eventually Leslie hesitantly replied, “Middlesex Cricket Club.” Wrong: the ‘M’ was for Marylebone – but how could a wee lad from post-war Plymouth be expected to know that, when Test and County cricket had not been played for six years, and frankly less than one in ten adults would have known the answer either. Leslie was to go on to achieve great academic success – he ended his career as a professor of chemistry with his own personal chair in the University of Surrey.

Somehow I managed at the age of fifteen to get a good School Certificate, the equivalent of today’s General Certificate of Education, and thoughts turned to the future. Nothing was further from my mind than a career in medicine. There were no doctors in the family.

I decided on a career in the Royal Navy; Dartmouth College and a midshipman’s uniform appealed. I passed the written exam with ease, did reasonably well before the selection board but to my surprise failed the medical because I had a cyst adjacent to a testicle. This had to be dealt with. While waiting for the surgery, I applied as an alternative to join the Army. I took and passed the written examination for the Royal Military College Sandhurst; the officer cadet uniform was also appealing. In order to make sure that I would not again fail the medical, I was admitted to hospital to have the cyst removed. This was my epiphany; a new world opened before my eyes. What interest, what fascination and what a way of life this doctoring has to be. Even the antiseptic smell of the hospital caused a frisson in my solar plexus. The team spirit and dedication were evident everywhere – the doctors were clever and kind, the wards well-organised, the nurses compassionate and disciplined and all practised their art against a backdrop of scientific knowledge with admiring, grateful and respectful patients – but most attractive of all, it was the doctors who were at the top of the hierarchy.

I became totally absorbed in the idea of medicine as a career, discovered exactly what I had to do to get into medical school and wrote to four London teaching hospitals for prospectuses.

In the meantime I was summoned to an Army establishment on Salisbury Plain for what was called the WOSB, the War Office Selection Board examination, which consisted of several interviews and various exercises involving ropes, planks, barrels and ladders. The object was to lead a group of fellow candidates through imaginary minefields or other military obstacles. Again I did reasonably well and this time passed the medical. The final interview was with a pleasant, ancient, kindly general with white hair, red tabs on his collar and a white walrus moustache.

His very first question was, “If the Army does not accept you, what will you do?” to which I immediately replied, “I’ll study medicine, sir.”

“And how would you set about doing that?”

I confessed that already I had prospectuses from Guys, St Thomas’, St Bartholomew’s and University College Hospitals.

“Well,” he smiled, “it appears to me that you really have your sights set on becoming a doctor. I suggest you do just that and then you can join the Royal Army Medical Corps.”

So I followed his advice and went to medical school but when the time came, the Army and Royal Navy were only offering short service commissions of five years so I chose to take a three-year commission in the Medical Branch of the Royal Air Force – uniform not quite as impressive but still not bad.

In May 1945 the war against Germany was over and three months later the Japanese surrendered. A further two months on, at the insistence of the Labour members of the National Wartime Government, a general election was called. An ungrateful nation kicked out Winston Churchill, replacing him with Clement Attlee, and a Labour government was voted in with an overwhelming majority.

For Britain (and for me) a new era dawned, that of the Welfare State. Utopian promises were made and included state funding for higher education and grants for students. Student loans and tuition fees did not exist in those days. Tony Blair introduced them forty years later and these days many medical students when they qualify embark on their careers with debts in excess of £30,000.

I applied to the medical schools in London and was accepted after the first interview at University College on condition that my Higher School Certificate ‘A’ levels were adequate. Because botany and zoology were not taught at Sutton High and I needed those subjects, I moved to Plymouth Technical College (now a university) and in a year passed those at ‘A’ level. I was awarded a Local Authority Scholarship and in 1952 entered medical school.

Two

THE FIRST EIGHTEEN MONTHS at University College was a slog through anatomy, physiology, histology (microscopic structure), pharmacology and biochemistry – all basic to moving on to clinical medicine. Anatomy was a particularly difficult subject which held little pleasure for me but, recognising its seminal relationship to the practice of medicine, I had to grit my teeth and get down to it.

Human anatomy consists of the most excruciating memory exercises; of memorising complicated structural relationships, insertions of muscles in bones, innervations of muscles, the courses of arteries, veins and nerves, the skull and skeletal anatomy, the anatomy of joints and the viscera; heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, intestine and not least the brain and nervous system.

To my surprise, I didn’t find that dissecting what was once a living body helped me to learn human anatomy.

There were sixty students in my entry and we were allocated a body in groups of six. We assembled in the dissecting room, a large, white-tiled, well-lit hall reeking of preservatives. Awaiting us were a dozen cadavers covered in white sheets on regularly arranged dissecting tables.

We gathered around our allocated tables, each group with an Anatomy demonstrator. The dean gave a short homily on our duty at all times to respect our subjects and we were off, the sheets lifted and the corpses revealed to our bulging, fearful, young eyes.

The bodies had been embalmed and immersed in formalin for months. It was difficult to think of these inanimate objects as holding a spark of life. All the tissues were stiff and inelastic; the skin was a muddy brown colour. The dissection of what looked like aged, dried, boiled mutton – as muscles appeared to me – bore no relationship to the neat illustrations in textbooks in which the arteries were red, the veins blue, the nerves yellow and the muscles a deep salmon pink. In the cadaver the viscera, heart, lungs, liver and intestines were all a greyish brown colour with a rubbery hard consistency.

We had been told not to ask about the origins of the body we dissected but one of my group somehow discovered that she was an Irish woman who had died a couple of years previously in what was in effect a Poor Law hospital in the East End of London. To our chagrin, when we got to dissect the pelvis, we discovered our subject had undergone surgery many years before and all the female bits were missing.

For the dissection of the brain, extras were distributed; we were each given one of our very own. I didn’t speculate on the source of mine.

One morning the dean appeared in the dissecting room accompanied by a uniformed senior police officer. A very serious problem had been brought to his attention by this inspector from Tottenham Court Road police station. The day before, an agitated old lady had presented herself at the desk of the duty sergeant and produced from her shopping bag a human ear. She had discovered it at the top of the escalator at Warren Street tube station, which happened to be nearby.

A quick count on our cadavers showed that all ears were present and correct. We pointed out, with perhaps a little more enthusiasm than such a misdemeanour warranted, that the Middlesex Hospital was also nearby and that its students were known to be a wild bunch. Later, we made enquiries through friends at the Middlesex. There were no missing ears there either… maybe the ear hadn’t come from a dissecting room?

Human physiology, the study of function, was as complicated as anatomy. Pharmacology on the other hand was fun; we experimented on each other and on one occasion studied the effects of smoking a cigarette on a fellow student who had never smoked, measuring pulse, blood pressure and observing how a normal person could turn an interesting shade of green.

Biochemistry was also amusing and we soon learned that the quickest way to identify a test substance was to taste it; unwittingly following the time-honoured medical practice of uroscopy – minutely observing the colour and clarity of a patient’s urine and tasting it. Sweet urine contained sugar and diabetes mellitus could be diagnosed confidently – mellitus from the Latin mellite, honeyed. Fortunately these days we have chemically impregnated sticks for testing urine for sugar and other substances.

After eighteen months, we sat our second MB (Bachelor of Medicine) examination; ‘A’ levels took care of the first MB, and the third MB would be the final qualifying examination. I struggled through second MB and, mildly surprised, passed.

In May 1954, I crossed Gower Street from University College to University College Hospital, donned a white coat, bought a stethoscope and entered the wards.

LONDON IN 1954 WAS A DIFFERENT world. Post-war austerity lingered. Trolley buses with overhead cables glided silently through the streets, steered by recently arrived drivers and conductors from the Caribbean without whom London Transport would have come to a halt. Beer, the life-blood of most medical students, was the equivalent in today’s money of four pence a pint and petrol less than two shillings a gallon… a pound would buy forty-five litres. The air was smoky and foggy, the buildings grimy. Jack the Ripper-type fogs occurred most autumn evenings. When the smoke of several million coal fires mixed with the dense fogs to create ‘pea-soupers’, traffic stopped, everybody coughed and not only the wards but the corridors of London’s hospitals were filled with bemasked chesty patients attached to oxygen cylinders.

My clinical training began with six months ‘clerking’ on the medical wards, the first three months on the Professorial Unit. Four patients were allocated to each student, and I remember mine as clearly as one remembers one’s first car.

The first was a drayman with Whitbreads Brewery, Henry Albert Wright. He was in his mid-fifties, a big jolly man with a florid complexion, a handlebar moustache and an explosive laugh which startled the ward. For years he had driven a cart, a brewer’s dray holding three dozen barrels of beer and drawn by two shire horses, in the area immediately around the hospital. Each morning he would collect his laden cart and the horses from stables next to St Pancras station and deliver three or four barrels of beer to ten pubs; at each he would pause for a quickie which consisted of at least three pints of beer. At the end of the day he would return to the stables, his cart loaded with empty barrels, make sure his horses were fed and watered, settle them down for the night and then go off with his mates for a proper drink of at least ten pints. He didn’t seem to need food and that worsened his problem, which was cirrhosis of the liver caused by his vast consumption of alcohol.

For introducing medical students to the art of examining patients, he was almost perfect. He displayed, or rather the medical registrar displayed for us, typical physical signs associated with advanced alcoholic liver disease. For starters he was mildly jaundiced, his skin was slightly yellow, the whites of his eyes were more obviously yellow. He had swollen parotid glands; these are the salivary glands at the back of the lower jaws, below the ears, the ones which become swollen in mumps. The skin of his chest and back showed numerous spider-like dilated blood vessels; the palms of his hands showed contractions of the tissue beneath the skin (Dupuytren’s Contractures, named after a French physician, Baron Dupuytren, who first described the condition and was by all accounts very bad-tempered); his abdomen was bloated with fluid and we could feel a large knobbly liver three inches below his right ribs. His lower legs were swollen with fluid which had gravitated to them.

Henry died of a massive haemorrhage three weeks after I clerked him. I attended his post-mortem examination. It was uncanny, uncomfortable, distasteful and frightening (leave alone the horrible stench) to see him opened from chin to pubis. The pathologist demonstrated the advanced cirrhosis of his liver, the large knobbly organ we had palpated when he was alive, and also displayed the immediate cause of Henry’s death, oesophageal varices – enlarged veins at the lower end of his gullet. They looked just like the varicose veins one sometimes sees on the legs of very fat ladies. Henry’s varices had ruptured; he had bled to death in an hour.

In contrast, my second patient was a small, skinny, bald-headed sixty-year-old Cockney called Bert. He had a syphilitic aortic aneurysm. Syphilis can affect any organ and system of the body. In times past it was treated with mercury salts which inevitably produced the witticism, ‘One night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury.’ The great Canadian icon of clinical medicine, Sir William Osler*, said, “The physician who knows syphilis knows medicine.” While that is no longer true these days, another of his aphorisms – “Look wise, say nothing and grunt, speech was given to conceal thought” – is eternal.

In Bert’s case, the syphilis bacteria had settled in the first part of his aorta (the body’s largest artery) just as it left his heart, a part of the aorta whimsically known as the Girdle of Venus. The infection had so weakened the muscles of the wall of the aorta that under the pressure of the blood, as it squirted out when his heart contracted, the wall ballooned outwards and a pulsating lump, about the size of a pigeon’s egg, could be seen forcing its way between the ribs in the front of his upper chest. In that era we had penicillin which would cure syphilis but Bert’s case was too late for treatment. We were told that eventually the aneurysm would rupture and a dramatic spouting of blood would rapidly see off poor Bert. We students goggled in awe at Bert’s lump, expecting it to burst at any moment.

My third patient was a pale wisp of a woman in her forties who had a severe iron deficiency anaemia and difficulty in swallowing. This was known as the Plummer Vinson syndrome (named after the physicians who had described it), a syndrome being a collection of signs or symptoms which consistently occur together to produce a recognisable clinical diagnosis. She exhibited a sign characteristic of iron deficiency anaemia, that of koilonychia – a word to roll around your mouth. Koilonychia indicates a spoon shaped depression in the finger nails. Her prognosis (her outlook) was excellent. The anaemia was easily treated with iron and the dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) due to a fibrous web at the lower end of her gullet, could be permanently relieved by passing a rod down her oesophagus, like a sword swallower, and dilating its lower end.

The fourth patient, again a tiny woman, was in her twenties. She had striking brown pigmentation of her face and body. On her hands the palmar creases and knuckles were almost black; she had dark patches in her mouth and the scar from an appendicectomy had turned black. Her chest x-ray showed a remarkably thin heart and her blood pressure was low. An x-ray of her abdomen revealed that her adrenal glands were calcified, a sure sign of tuberculosis. She had Addison’s disease (described by Dr Thomas Addison in 1849) caused by failure of her adrenals, the glands which sit on top of the kidneys and produce cortisone and other hormones. Adrenal failure due to tuberculosis was not uncommon fifty years ago; tuberculosis is making a comeback these days and is often associated with HIV infections which bankrupt the body’s immune defences. Fortunately for our patient, cortisone had been introduced five years earlier and she made a good response to treatment.

In my clinical studies, I soon learned the rule that the successful practice of medicine depends on diagnosis, diagnosis and diagnosis. Without the correct diagnosis, proper management leading to a cure is unlikely. Diagnosis depends on three things: taking a detailed case history, performing a good physical examination and carrying out investigations in the laboratory, in the x-ray department, by various scans, radio-isotope studies, biopsy examinations, endoscopic examinations and function studies – but no matter what miraculous advances occur in investigating patients, the starting point will always be the doctor taking the history and examining the patient.

Occasionally a single physical sign can give an instant diagnosis, a ‘spot diagnosis’. Some five years later while doing a locum in general practice, I saw a young man with vague symptoms. On examination I found a brilliant cobalt blue line along his gum margins. Instant diagnosis: lead poisoning. Asked what his job was, he replied, “Burning old car batteries.” The fumes of burning batteries contain lots of lead.

I was a pretty average student at school, strived hard to get my ‘A’ levels in botany and zoology in a year and struggled with the second MB – but it was clinical medicine that hit the spot. I came alive: this was it. The Sherlock Holmes approach – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was an Edinburgh doctor – was fascinating; discovering clues from the history and examination, confirming suspicions by investigations and then treating according to a proper diagnosis was immensely satisfying and exciting. What other job could be so great?

SIX MONTHS SURGERY FOLLOWED THE medical clerkships. We were now called ‘dressers’ which added a certain cachet. We were introduced to the mystique of operating theatres, of surgical rituals, of the effects of trauma, and had a spell in the Casualty department – so busy you scarcely had time to turn around before the next case appeared.

When I was a student at University College Hospital, professorial ward rounds always began at the front entrance of the old hospital, the redbrick cruciform building in Gower Street, now dwarfed by the huge brand new UCH in Euston Road.

At the appointed hour a beadle in a maroon gold-piped uniform with a shining top-hat threw open the glass front doors and through them would march the professor followed by lecturers, senior registrar, registrars and housemen – then we dozen or so students would tag along behind. We would first ascend a short flight of steps flanked on the left by a bust of Sir John Blundell Maple Bart MP and on the right by a bust of Sir Robert Liston.

Sir John Blundell Maple Bart MP was the wealthy owner of a huge furniture shop in Tottenham Court Road, just around the corner from the hospital: Maples. He was extremely successful and donated £200,000 (a great deal of dough in those days) for the hospital to be reconstructed in 1881. I was told as a student that his patronage stemmed from the life-saving care he received at UCH after he had been run down by a hansom cab in Tottenham Court Road. That could be urban myth; I’ve not been able to confirm that story.

The other bust was of the most colourful surgeon in the history of UCH – maybe indeed of British history – Sir Robert Liston. A Scotsman, born a son of the manse, Sir Robert trained in Edinburgh and became surgeon to the Royal Infirmary there. But his personality was abrasive and outspoken; he was so quarrelsome that his fellow surgeons banned him from working in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. Sir Robert took to heart the observation of that great lexicographer, Dr Johnson, that the “noblest sight a Scotchman ever sees is the high road that leads him to England” and moved south. In 1835, he was appointed the first Professor of Surgery at University College Hospital.

According to doctor and author Richard Gordon (Doctor in the House etc) he rapidly established a reputation as the “fastest knife in the West End”. In pre-anaesthetic days, the quicker the surgeon, the better his results. Sir Robert’s results were the best in London: only one in ten of his patients died of hospital gangrene; at Guy’s it was one in four. Not surprisingly, he had a good private practice.

Sir Robert was tall, well over six feet; he was strong and fit. I remember a story of how he chased and collared a reluctant patient. The man was next in line for surgery but fled in terror when he heard horrifying screams coming from the operating theatre. The poor patient hopped off as quickly as he could (Sir Robert was going to chop off his bad leg). The operating theatre was at the very top of the hospital and the patient made it as far as the gents’ loo in the basement (it’s still there with white tiles and shining brass fittings). Sir Robert found him crouched and cowering; he picked him up and slung him over his shoulder; and after sprinting up a dozen flights of stairs he threw him on the table, had him strapped down and took his leg off in his standard time of two and a half minutes.

Those were brave days indeed – in my time as a student the operating table Sir Robert used was displayed in the medical school pathology museum. To gaze at it scared the daylights out of me. Made of wood, it had half a dozen slots for leather straps down each side to secure the patient’s body and more around the curved top for firmly securing the patient’s head. There were detachable extensions for the legs; they could be removed in a flash, just like patients’ legs.

Sir Robert, like all trendy surgeons, operated in wellington boots and a long green frock-coat stiff with dried blood and pus. We were still waiting for Lord Lister (I later worked for his grandson, William, in Plymouth) to introduce his carbolic spray and Semmelweiss in Vienna to make himself very unpopular by showing that it was the medical students and doctors themselves who carried infection from patient to patient. No surgeon would dream of putting on a clean coat or scrubbing his nails; that was for pansy types… like physicians.

One of his most famous patients was a man with an enormous scrotal tumour; it was so big he had to accommodate his scrotum in a wheelbarrow when he wanted to move about. Sir Robert removed it in four minutes flat; it weighed forty-five pounds… just try and imagine that!

In another memorable operating session, he amputated a man’s leg in under the standard two and a half minutes, but such excessive speed has its price. When he chopped off the leg (which fell into the usual receptacle – a box of sawdust) with the ultimate slice, to the surprise of his dresser holding the limb, three of the dresser’s fingers accompanied the leg and plopped into the box. Then he accidentally sliced through the coat of a distinguished surgeon leaning over to get a better look.

The surgeon, an elderly visitor who was there to observe the Master’s technique, had a heart attack and dropped dead on seeing the knife flash so close by him. Both the patient and the dresser died of hospital gangrene a few days later. Not infrequently operations at that time carried one hundred per cent mortality; but three hundred per cent was surely a record for one surgical session.

On another occasion, he was so speedy he took the man’s testicles with the final exuberant slice; that patient was spared a eunuchoidal existence as he also died of hospital gangrene a few days later.

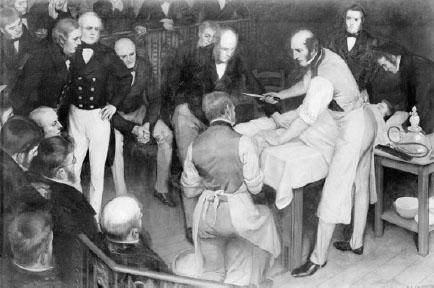

Sir Robert Liston’s most famous surgery took place at University College Hospital on 21 December 1846. It was the first operation in Europe carried out under general anaesthesia. Ether was used. The patient was a butler called Robert Churchill and he needed to have a mid-thigh amputation for a malignant tumour of his leg.

First operation performed in Europe under ether anaesthesia, UCH 1846. Wielding the knife is Sir Robert Liston. Standing at the left is Lord Lister who first used a carbolic acid spray for antisepsis. (Photo: Wellcome Library, London.)

A large and eager audience squeezed and jostled on tiers in the circular operating theatre. Dr William Squire was the anaesthetist. He determined to put on a show before the patient was brought in, so he asked if any of the assembled medical students would volunteer to be anaesthetised.

Sir Charles Brown, who was present, described what happened in his memoirs, Sixty Years as a Doctor:

A young man called Shelbrake, of powerful build and a good boxer at once came forward and lay down on the table. After he had inhaled ether for half a minute he suddenly sprang up and felled the anaesthetist with a single blow and scattered the students before him like sheep before a dog. He soon regained his senses and the patient was then brought in.

Even today’s TV doctors don’t give such entertainment value.

Sir Robert then took over the show. “Today, gentlemen, we are going to try a Yankee dodge for making a man insensible,” he announced to the assembled throng.

Dr Squire, by now chastened but recovered, introduced a red rubber tube into Mr Churchill’s mouth and within a few minutes Churchill was unconscious. “Take your watches out, gentlemen!” commanded Sir Robert – his usual cry: he always liked to be timed – as he advanced on his patient.

He did the job in thirty-two seconds (no screams or wriggling). A few minutes later Robert Churchill came round and asked, “When are you going to start?” The gallery erupted in cheers and laughter. But when Churchill raised his leg and saw the stump he burst into tears.

AFTER SURGERY THERE WAS Obstetrics, where each student was required to deliver twenty babies. My first delivery was of a rather elderly lady, in her first pregnancy in her late thirties (elderly for those days). All went well. I was proud of myself. The swaddled infant was placed in a cradle, an open metal box suspended by metal hooks on a stand with the head pitched a few degrees down. I asked the new mother if she would like to hold her baby – she would. As I picked the baby out of the cradle, I hit its head against the metal hook with a clunk. “Sorry,” I said, “it’s my first baby.”