__________________

Copyright © 2014 by Susie Hara. All rights reserved.

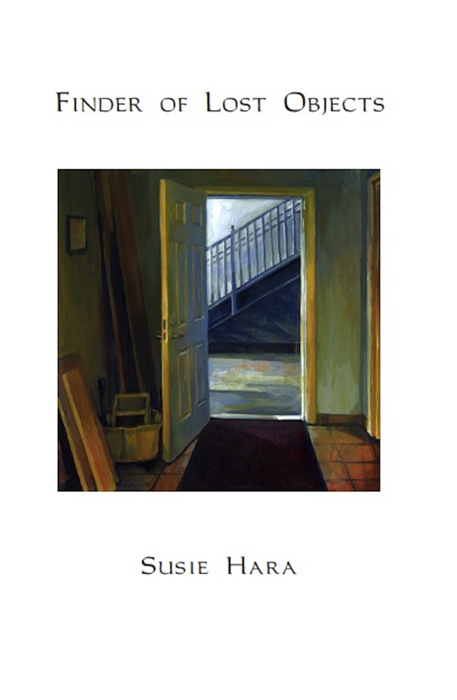

Cover and book design by Plainfeather Printworks.

Front cover: Wayne Jiang, “Backdoor #1.” © 2013

www.waynejiang.com

ISBN 978-0-9835791-6-8

ISBN: 9781483523422

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014930216

Ithuriel’s Spear is a fiscally sponsored project of Intersection for the Arts, San Francisco.

www.ithuriel.com

October, 2005.

ON A SUNNY SAN FRANCISCO MORNING after a string of foggy days, I sat on the red exercise ball in my office, wondering how I was going to pay the rent. When Grace Valdez walked in the door I stood up, and the ball rolled away from me on its slow trajectory along the sloping floor.

“I saw your sign,” she said. “I want to talk to you about finding something I’ve lost.”

I held out my hand. “My name is Sadie. Sadie García Miller.” We shook hands. Hers was cool and dry.

“Grace.” She paused. “Valdez.”

“Please have a seat.”

She surveyed the rolling ball and my chairless office. I pulled out a folding chair and set it up for her. I retrieved the ball and sat back down behind my desk.

Grace Valdez looked like she had blown across town from a more upscale neighborhood, the Marina or Pacific Heights. She looked about ten years younger than me, around thirty. Her jagged-cut hair was shot through with subtle blond highlights, and her tawny skin seemed to glow. She wore designer jeans and a nice pair of strappy heels.

“What is it you’re looking for?” I asked.

She picked at her thumbnail cuticle. “My brother.…”

“Ms. Valdez.” I hesitated. I needed the money. “I’d like to help you, but I don’t find missing persons. I find lost objects. I can refer you to an excellent private investigator.”

“No—no.” Her voice was breathy, Marilyn-Monroe-like.“ I mean, my brother has what I’m looking for. The book. My brother has it.”

“A book.” Maybe I said it too loudly. Ms. Valdez flinched. Pretty jumpy for a woman in search of a simple book. But then, nothing is as it seems in my line of work. People say they’re looking for an object, but they’re really looking for a whole lot more. A way to fill up the emptiness, a way to cover the gaping hole. I’m an expert on that.

“Mind if I smoke?” I said.

She smiled for the first time and, taking out a pack of Camel filters, offered me one.

“Thanks.”

I lit our cigarettes with the snap of my lighter.

She drew on her cigarette. “This is nice. You don’t get to smoke indoors much anymore.”

“I know.” I usually didn’t smoke in the office, actually, because most of my clients or would-be clients would run screaming from the smell of cigarette smoke. But this was clearly an exception. I reached into the desk drawer, brought out the ashtray, and put it between us. “This might seem obvious, but— have you asked your brother to give the book back?”

“Of course. He says he doesn’t have it. But he does, I know he does. He stole it from me, the—” she stopped herself— “jerk.”

“I see. What’s the value of the book?”

“I don’t think it has much financial value.”

“Sentimental value, then. You want that particular book, no other copy will do, is that right?”

“That’s right,” she said, and her eyes darkened. “The book is inscribed to me from my mother. She used to read it to me when I was a child. Since she’s been gone, I have always treasured it.”

“Gone?” I said. “Do you mean—”

“Heart attack. When I was twelve.”

“I’m sorry.” I didn’t tell her we had something in common. I chased away the hollow feeling in my chest.

“Ms. Valdez. I have a few questions, if you don’t mind.” I opened my notebook. “When was the last time you saw your brother?”

“It’ll be two years ago this Christmas.”

“Did you ask him then if he had the book?”

“No—it went missing after that.” Her voice was edged with resentment.

“And you contacted him?”

“Many times, but he never responded.”

“Did something happen between you that caused him to break off communication?”

Her eyes shifted to the right. I followed her gaze. Where she was looking there was nothing interesting, only an oak filing cabinet; no pictures on the walls, no bookcases, no potted plants. And I knew, just like my grandpa taught me, she had to be hiding something.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“Where does your brother live?”

“He used to live in Fresno, in the house where we grew up. But when I call, I either get the machine, or one of our tías picks up—they live there too.”

“Did you ask your tías?”

“They won’t talk to me either.”

“And why is that?”

“It doesn’t matter,” she said, waving away a puff of smoke.

I wanted to tell her yes, it does matter. Sometimes the smallest detail leads to the missing object. Instead I let the silence hang between us, hoping it would draw her out.

“My aunts thought,” she said, “Joey and I were having… an improper relationship. We weren’t. They never believed me. I became the scapegoat. Know what I mean?”

“They blamed it on you and not your brother?”

“Of course,” Grace said, with a bitter smile.

“Yes, we always get blamed, don’t we? ” I shook my head.

She nodded. There was a hardness in her eyes, and under it, a hint of hurt. We smoked in silence for a time.

“What’s the name of the book?”

“The Journey, by Renata Holland.”

I made a note of it. “When was it published?”

“I’m not sure exactly, but—I think in the sixties.”

“What’s it about?” I drew a quick sketch of a book in the corner of my notebook.

“A young girl who goes on a dangerous journey to rescue her father.” A shiver ran through me. A girl trying to save her father. “That sounds intriguing,” I said. “So it’s a—Young Adult book?”

“Yes, that’s what they call it now.”

“What does the cover look like?” I asked.

Her gaze turned inward. “A pale green background. A red-haired girl perched in a tree, looking up at the sky, at a full moon and stars. And it has one of those gold medal things on the cover, a Millhouse Award.”

“And the inscription—what does it say?”

“To my daughter, Graciela.”

In the whisper of sadness that flickered on her face, I caught a glimpse of a little girl, always on her own, an outsider searching to belong.

“It’s a special book, then. A keepsake,” I said.

The light in her eyes shifted, and she looked at me directly. “That’s a good way of saying it. Yes, it’s my talis— ”Her face colored. “I have to get it back. I can’t stop thinking about it, like when you need a cigarette, except you can’t have one but you can’t stop thinking about it either.”

I perked up. The nature of the client’s fixation always contains clues to the lost treasure. To find the object of desire, follow the obsession. “When you think about the book, where do you see it?”

“I picture it… in my mother’s hands. As she read to us.”

An image came into focus of a warm, maternal woman with a soft, curvy body, a coil of braided black hair pinned up with tortoiseshell combs, her reading glasses perched on her nose. Along with the picture came a feeling of sadness, washing over me and settling in my chest like a bad cold.

“Thanks,” I said. “These questions help me find things.”

“I understand. I’m psychic too. I’ve tried and tried, but I can’t visualize where the book is now.”

I started to tell her I’m not psychic, I just use my senses and intuition to lead me to the lost item. But I left it alone. Better to let my actions speak for themselves.

Pulling out my contract, I told her I’d be happy to take her case. She took out her reading glasses and read the contract word for word. She didn’t blink at the fee schedule or the upfront retainer. We signed the agreement and she wrote me out a check. I tucked it away, silently thanking the gods of commerce. Just in the nick of time to cover my rent.

“I’ll need a photo of Joey,” I said. “Not digital—a print.”

“I’ll get that to you.” She stood and put the contract in her bag. “Ms. García Miller….”

“Call me Sadie.”

“Sadie. I’m wondering.” Her eyes burned. “Do you know St. Anthony?”

I thought of saying that I was half-Catholic, half-Jewish, and these two halves did not make a whole. “I have to confess, I’m not Catholic,” I said, hoping she’d get the joke.

“You don’t have to be Catholic. You’re familiar, though?”

“Yes. Patron saint of lost objects.”

“I’ve been praying to him for some time. When I saw the sign in your window today I knew it was meant to be.”

“Maybe it was,” I said, gathering up the paperwork, even though I wasn’t sure if I agreed with “meant to be” as a concept. I felt more affinity to Insh’Allah, an Arabic phrase, literally “God willing,” but which in my rough translation meant that some things were simply out of our control.

“By the way,” I said, “I’m from the Central Valley too. Bakersfield. Born and raised. Are you from Fresno originally or—.”

“No,” she said, shoving her cigarettes into her bag, and she was gone, slamming the door behind her. The Tibetan bells hanging over the doorknob clanged violently, and in the wake of her departure the louvered blinds tapped on the glass.

I finished my sentence to the empty room. Something about my question had pissed off Grace Valdez. But in my business, anger is a good thing. Like a big yellow traffic sign with a solid black arrow, it tells me—go this way.

Pushing my hair out of my face and tucking it behind my ear, I felt something odd: no earrings. Wait a minute. I’d worn the opal ones today, for luck. I touched my earlobe on the other side, and sure enough, the earring was in place. No, no, no. Impossible.

I searched every corner of my office, behind the oak filing cabinet and under my desk, and scoured the back room, around the sink and counters, telling myself it had to be there. But the truth was, I could have lost it anywhere: at home, on my way to the office. I sat down on the ball, trying to hold back the tears.

I told myself the earring would turn up. I would find it, just the way I found things for everyone else. The first time I discovered my penchant for finding missing objects, I was eleven years old.

“Son of a bitch.” Dad was leafing through piles of paper—on his desk, on the kitchen counter, in the living room, swearing and sweating as he went.

I put my hand on his shoulder. “What are you looking for, Dad?”

“A document,” he said.

“I can help you.”

“Sadie, I’ve looked everywhere. If I don’t find it, I’m screwed. Royally screwed. I’ll lose my job.”

This was weird—he’d never said anything like that before. “Dad. What do the papers look like? What colors? Tell me. I’ll find what you’re looking for.”

He shook his head, but then said, “OK. A bunch of papers. White. With black type and a big red stamp on each page that says ‘confidential.’Held together at the top with one of those two-hole binder clamps.”

“Silver clip thing?”

“Yes.”

“OK, Dad. Let me look.”

I started in the kitchen, making my way through every room of the house. I looked everywhere: no luck. I sat down on the couch and closed my eyes. I thought about Dad’s union, the United Farm Workers. I had just finished a paper on the Grape Strike and now I understood there was a whole other side of the UFW. I knew them as family friends—the other organizers and all the field workers who rumpled my hair and called me Sedita—but I’d never realized before that they had made history.

When I thought about La Paz, the union headquarters, I got a fuzzy feeling in my chest. I was sore from shooting hoops the day before, and it seemed like my aching arms and shivery chest were all working together to give me a message. About the papers. I looked for a picture in my mind, but it was blank. Then the body feelings got so big they made me stand up and go outside and look at the moon, which was almost full. Right in front of me was the car. The car. The fuzzy feeling exploded. I checked the front and back seats, then went down on my knees and looked underneath the passenger seat. Papers. I pulled them out. White, with a silver two-hole binder clip—.

“Dad! Dad!”

He ran out of the house, and we whooped and hollered and he lifted me high in the air and kissed me.

“You found them in the car? Where? I looked all through it,” he said.

“Under the passenger seat.”

“I swear I looked there.”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Maybe it was hiding from you.”

“Sedita,” he said, his face lit by the moon. “You have the knack. Just like your mother.” His words settled into my heart. A knack. From my mother.

Just as the memory of that day had unfurled and wrapped itself around me, it now folded itself back up again. I did what I always do when I want to forget all that. I opened my laptop and got to work.

My online search for Grace’s brother turned up a zillion José Valdezes but only a few José Ruiz Valdezes, one of whom kept showing up as a cast member at community theaters in the Fresno area. A couple of feature articles in the San Joaquin Valley Spanish-language papers mentioned a “Joey” Valdez.

I found The Journey and ordered a copy, then went back to looking for Joey Valdez. Traipsing through a labyrinth of websites, clicking and skimming, I went from one site to the next and the next and the next. Some time later, I heard the Tibetan bells and came out of my online trance long enough to look up from the screen. But it was only my cat Emma, batting the bells with her paw.

There was something tugging at the back of my mind. What was it? Someone I was supposed to call? Daniela. I texted her, knowing my ten-year-old niece would never actually answer the phone. <What day is UR school play? I want to come. I’ll be there rooting for you.>

I always had to fight off a nagging sense of worry about my niece, even when nothing was wrong. Lately, though, she was a regular drama queen. Maybe I had to get used to it— she was a preteen now. But it seemed like there was a layer of anger underneath her sass. Had something happened…? It was probably nothing, I told myself. She’ll be OK. She’ll be fine.

I locked up my office and walked the six blocks to my truck. It was already eighty degrees, and when it’s October in San Francisco everyone celebrates the warm weather, riding their bicycles, putting on their cutoffs and tank tops, and— for some women (plus a few men)—donning their skimpiest dresses. I’d taken the opportunity to put on a red-and-yellow backless sundress, a vintage number in a crinkly 1950s rayon. Strolling down Valencia Street, I took in the lovely sight of skin—joyfully exposed in a collective festival of fleeting summer.

A half hour later, I was on the road to Fresno.

The drive to Fresno goes right through the heartland of California. The farms and agricultural corporations of the San Joaquin Valley are key to the state economy, even though the reality is that the top cash crop of California is marijuana, grown farther north, in beautiful Humboldt County. But for mainstream agriculture, this swath of land is essential not only to the state economy, but also to the exploitation and employment of thousands of migrant farm workers, generations of whom have settled in the San Joaquin Valley, aka the Central Valley, aka the Valley.

As I drove south on Interstate 5, amidst the yellow-brown hills and neat rows of cotton, alfalfa, or nut trees, I had plenty of time to think. The landscape reminded me of growing up in the Valley. I remembered all the times I’d driven with my dad, miles and miles of freeway and road, for his work, but once in awhile—for a special trip. The memory of my twelfth birthday came, unbidden.

Dad was driving. He’d refused to answer any of my questions, but since I hadn’t had to get dressed up, I knew we weren’t going to a play or a restaurant. But for sure we were going to Los Angeles, I could tell by the route. I couldn’t believe it when we got there.

“The Forum! Oh my gosh, we’re going to see the Lakers! You said we couldn’t go—you sneaky bootface.” Throwing my arms around him, I kissed him five times. He looked pretty proud of himself as he pulled the Volkswagen Bug into the line of cars waiting to get into the parking lot.

“OK, Punkamonk. I have to drive.” But he was grinning.

At the start of the game, the sound of the shoes on the court—jeet, jeet, jeet. It smelled like floor varnish and hot dogs, and all the mixed smells of a gazillion people. The lights were so bright the floor looked like polished amber. “I don’t see him, Dad. You sure he’s here?”

“Right there. In the corner by the—”

“I see—I see him!” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. I’d read up about him and watched every game I could on tv, at least when I was allowed to.

I hugged myself, and hugged my dad. We couldn’t see very well way in the back, but it didn’t matter. We were here. Watching the Lakers play the Blazers. I still couldn’t believe it.

Lately, my Dad didn’t look so sad and tired all the time. I knew he still missed my mother, but now he seemed different—he joked around more, and he acted more Dad-like. I was pretty sure the Bad Time was over.

I kept looking over at him—he’d never cared about basketball—just shot hoops with me once in awhile, and hardly ever watched a game on tv. But now he was following every play—his eyes darting back and forth—and when Kareem did his sky hoop and everyone jumped to their feet, Dad did too. He was yelling right along with me.

After the game, we went to Baskin-Robbins, my favorite place to eat. “Mmm.” I took my first spoon of vanilla ice cream with a glob of hot fudge and whipped cream and savored the cool, creamy sweetness.

“You win some, you lose some,” Dad said.

“It’s OK, Dad, really. Winning doesn’t matter, as long as you play a good game. Right?”

“Right, Punkamonk.”

He took something out of his pocket and handed it to me. It was a small square white box. I opened it. Inside, nestled on the cotton was a pair of earrings, with luminous, round stones. When they caught the light, they were blue, coral, and turquoise.

“Wow. Thank you, Dad.” He’d never given me jewelry before. I wondered if this was Gloria’s idea, but I didn’t say anything.

“Do you like them? They’re opals.”

“Love them.” I took out the gold posts that Gloria had given me, placed them in the box, and put on the birthday earrings.

“Beautiful girl,” he said.

I hugged him. I knew I wasn’t beautiful, but it was still nice.

“Dad. Tell me something.”

“Anything.”

“I didn’t think you liked basketball.”

“I never said that.”

“Yeah, but I just… know. So—do you like basketball now? Now that you’ve seen Kareem and all?”

“It was a good game, and the best part is that I was there with you.”

“But do you—like basketball?

“Not as much as you do, Sedita.” He grinned and took a big bite of whipped cream, giving himself a perfect white mustache.

* * *

I exited at the town of Los Banos on 152 and took the turnoff to 99. It was warm in the city but here it was broiling. It had to be almost 100 degrees. I felt the sweat rolling down between my breasts to my belly.

My thoughts turned to what I’d found out so far on the Grace Valdez case. The obituary for the father, Rodrigo Valdez, said he was survived by his children: José Ruiz Valdez, Teresita Ruiz Valdez, and Graciela Valdez. Why wasn’t her name Ruiz Valdez, like the other siblings? The obit on Mr. Valdez also mentioned the earlier passing of his wife, the beloved Consuelo Ruiz Valdez.

The Valdez neighborhood was a mix of solid-looking wood-frame houses from the early part of the twentieth century, along with stucco buildings that looked like they were built in the 1940s, and newer, ranch-style suburban houses. I parked my truck in front of the Valdez home, a white stucco house with a red-tiled roof. A beautiful, ancient bougainvillea climbed up the side of the house, but the grass in the front yard was dried out, and the rosebushes lining the driveway looked neglected.

I rang the doorbell. No answer. I tried the door. Locked. I looked in through the window, through a crack in the drapes, but it was dark.

A teenage boy was riding by on a red bicycle. “Who are you looking for, Señora?”

I didn’t like being called Señora — I’m not that old, but I did appreciate that he spoke to me in Spanish. So many people look at my curly blond hair and don’t get it that I’m Latina.

“I’m looking for Joey Valdez, or whoever lives here now. I’m offering gardening and landscaping services.” I answered in Spanish and gestured to my truck. When I first bought the pickup, I’d planned to paint over the “Parker Landscaping and Gardening” sign on the side, but then decided not to when it turned out it came in handy for times like these.

The boy switched to English. “Joey’s been gone for a long time. He lives in Mexico City now. His tías live here, but they’re at work. You sure you’re not looking for Joey for something else?”

“Why would I be looking for him?” I smiled.

“I just thought, you know, Hollywood.”

“Hollywood?”

“You know—Joey’s a star—everyone used to watch him on Amor Perdido,” he said.

“Well. I might be a reporter from Hollywood.” I said, grinning. “Or else I’m a gardener. Did you watch his show?”

“It’s a telenovela, you know. I’m not into it. But mi mamá and mis tías, they’re all, ‘we love him.’Joey has a different name now. Like a professional name. It’s Ramon-something.”

”So he’s famous. Cool. I’d like to see that show. Do you know his whole name—Joey’s professional name?”

The boy shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know, but he’s probably got, like, a website.”

I handed him my card, which read: Tanya Parker, Gardening and Landscaping Services. “Entonces—gracias por todo,” I said.

“OK, de nada,” he said, riding away.

I drove to the old downtown area, looking for a place to eat. An image of Grace kept floating in my mind. Not so much a picture of her, more a feeling. Anger and sadness, all wrapped up in a package of what? Betrayal. That was it. The injustice of the betrayal was somehow embedded in the lost book. And now a picture did come into my mind: money. There was something to do with money in all this. But how could betrayal and money lead me to her book? And why was the book so important to her? Was it really because her mother gave it to her, or was there another layer?

I scanned the streets for a family-owned-type place, not a chain with a California-cated version of Mexican food. I wanted some tamales, bad. I had grown up eating Mexican food. Tortillas, frijoles, tamales, chile rellenos, and enchiladas—these are my comfort foods, not macaroni and cheese. I found what I was looking for: Dolores’s Place, Taqueria and Restaurant. The sign said “Patio in Back.” I went straight through to the patio, an oasis of sorts. Magenta-blossomed trees provided shade, and a fountain in the center made a soothing sound. I found a table and sat down with my notebook to think about the case.

“Can I get you some coffee?” the waitress said, handing me a menu.

I had to stop myself from gaping. She was the exact image of my babysitter Gloria Lopez, who came into my life when I was five years old, right after my mother died. She was only twenty back then, barely out of her teenage years, but to my eyes she was all grownup and wise, like a giant, glamorous goddess. From the beginning, she was never just a babysitter, she was always my Tía Gloria. The waitress, with big eyes, lots of cleavage, and an air that was warm and business-like at the same time, reminded me of the young Gloria. I smiled. “Yes, coffee, please.”

I missed her. If I drove another couple of hours I’d be there. As usual, I wanted to see her and I didn’t. Familia, so complicated. But spending time with her always turned out to be a good thing. And, I reminded myself, Gloria’s so lonely these days, and it seems to make her so happy when I visit.

My thoughts circled back to the case. So Joey was a soap opera star in a telenovela. I hadn’t found that in my Internet search, but now it turned out Joey had a professional name. Odd that Grace didn’t know about it—but she seemed cut off from this world, of tías hooked on novelas, and a town where everyone knows your business. Grace had left Fresno behind, along with the legacy of farm worker parents who worked their butts off so their kids could get out of the fields. Even though she obviously had a good job or some kind of real money coming in, she hadn’t lost her working-class edge. I liked that about her.

I ate my tamales, which were OK, as long as I didn’t compare them to Gloria’s, which were incredible—moist, delicately flavored. Not dry like these. Every Christmas I used to help her make dozens of tamales, and then we’d have a big party and they’d be gone in no time. I drank my coffee and looked over my notes on the Grace Case so far. NEXT STEP? I wrote in my notebook. I made a quick sketch of a clock. I could wait a couple of hours until Grace’s tías got off work. Or: I had another alternative. With a few quick lines, I drew a house. I could go back to the Valdez house and look for the book in my own fashion.

I parked a couple of blocks away. There were no cars in the driveway or in front of the house. It was quiet—everyone was at work or school. I took out Grandpa’s lock-picking kit, put it in my bag, and slipped on my gloves.

Strolling over to the Valdez house, I did a quick scan of the neighborhood. At the back of the house I stood still for a moment, and listened with every cell in my body. Just because the young man on the bicycle had said they were at work, and just because there was no car in the driveway, that didn’t mean no one was home. But I didn’t hear anything, not a tv, no water running, nothing. I scanned the surrounding houses—no nosy neighbors peeking. I tried the windows—no go. I figured the back door was locked too, but my private-investigator friend Boyko always says: “Try the obvious thing first.” I put my hand on the knob—it opened.

The house was quiet. I found myself in a laundry room alcove, with a washer-dryer and a perfectly ordered row of supplies: laundry soap, bleach, stain remover, and those wispy sheet things that people put in their dryers. I stepped quietly into the kitchen. It was spotless. Someone was a compulsive cleaner in this household.

I tiptoed into the living room. So far so good. A tv and a worn rust-colored couch and armchairs, circa 1970. Then a sound came from the back of the house. Shit. My heart hammered in my chest. They were the softest of footsteps, like someone trying not to be heard. I started to hightail it out of there but stopped. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a movement close to the ground. A white cat stepped lightly into the room, claiming it as her own, with a blue-eyed glare. She rubbed up against my leg.

I sighed with relief but my heart was still pounding. I stood for a moment, poised for flight. Then, shaking my head, I braced myself, and pushed onward.

The hall off the living room led to a bedroom. Twin beds, each meticulously made and covered with a chenille bedspread, and another tv. On one of the bedside tables was a magazine, and from its cover a beautiful woman in a low-cut dress gazed at me with wistful abandon. I looked at the magazine more closely: TV Y Novelas. Everything you always wanted to know about novelas but were afraid to ask. I wanted to take it with me but that would be wrong. I made a mental note to pick up a copy of the magazine when I got home.

Down the hall I found another bedroom. Bingo. It was like a museum to adolescent boyhood. Football trophies, posters of local theater productions, and action figures. There was a tv (the third, and counting), but no computer and— most important—no books. Was that possible? I opened the closet—some men’s shirts and pants, a couple of sports coats, but nothing else. I looked around the room—surely Joey had read something when he was growing up? I went through the dresser. No printed material of any kind.

The hum of a car interrupted my search. Fuck! Was it in the driveway or on the street? I dropped to a crouch and scuttled to the kitchen. I rose my head slightly to get a look out the window, and then ducked. A blue Ford Escort was in the driveway. I was looking for a hiding place when I heard the terrifying clicking of heels on pavement. The skin on my neck prickled and I was sweating like crazy. But the next sound, thank God, came from the front porch—keys jangling, the turn of a lock. I made for the back door and slipped out quickly, then tore across the backyard. I crouched behind a bush while I got my bearings. I could try to scale the fence right away, or just wait there until it got dark and then creep out along the driveway. From my vantage point, I saw movement through the back window. The sound of a tv blared. Good. I edged my way over to the fence.

“Hey! Qué hace? What are you doing?” A short, round woman yelled at me from the back doorway. “I’m calling the police.”

I tore to the fence, got a toehold, climbed over, and jumped down. I ran like hell down the alley and then forced myself to walk slowly and casually down the neighborhood streets, back to my truck. In my whole career I had never experienced being interrupted while I was in the midst of doing the right thing. And even though the yelling woman did make me feel a moment’s guilt, I knew that ultimately, as long as I was doing the humane, the ethical, and the righteous thing—in my own version of morality culled from by my father’s, grandfather’s, and Gloria’s practical moral code—I was not breaking any damn law. This was my litmus test. The book truly belonged to Grace, so if I had to break and enter (although I hadn’t really “broken” anything) to find Grace’s rightful object, I was doing the right thing.

I practiced some deep breathing and kept to the speed limit as I got out of town. I didn’t hear any sirens, but that was no surprise—Grace’s tía knew, surely, that if you’re not white, the last thing in the world you want is the police.