Also by the Author

Nonfiction

Friends in High Places, Third Edition

Good Questions

Jesus 2.1: An Upgrade for the 21st Century

Fiction (written under the pen name Thomas Henry Quell)

Wrathworld

The Princess and the Prophet

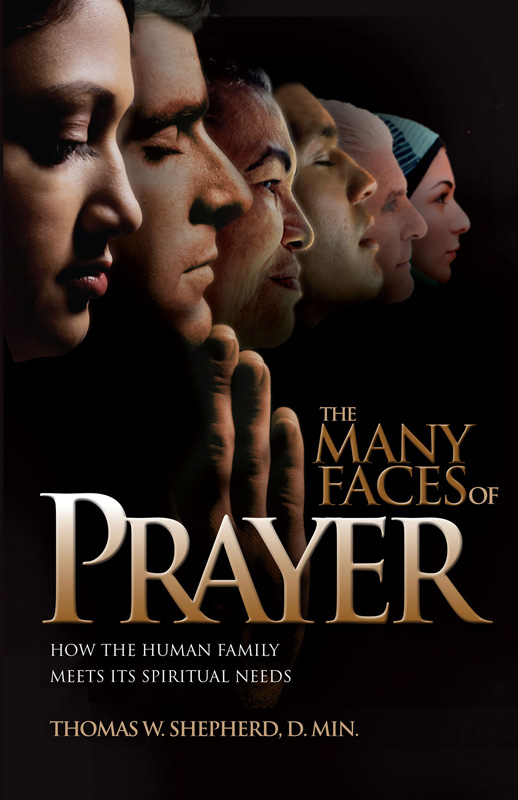

The Many Faces of Prayer

A Unity Books Paperback Original

Copyright © 2013 by Thomas W. Shepherd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from Unity Books, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews or in newsletters and lesson plans of licensed Unity teachers and ministers. For information, write to Unity Books, 1901 NW Blue Parkway, Unity Village, MO 64065-0001.

Unity Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases for study groups, book clubs, sales promotions, book signings or fundraising. To place an order, call the Unity Customer Care Department at 1-866-236-3571 or email wholesaleaccts@unityonline.org.

Bible quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

Cover design: Terry Newell

Interior design: The Covington Group, Kansas City, Missouri

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012951544

ISBN: 978-0-87159-362-7

ISBN: 9780871597540

Canada BN 13252 0933 RT

For all my students,

past,

present,

and future.

Foreword by Rev. Tom Thorpe

Preface

Invocation

| 1 | Communication or Reflection? |

| 2 | The “Let It In/Let It Out” Controversy |

| 3 | Primordial Religion and Deep History |

| 4 | Roots of the God Concept |

| 5 | Evolution of the God Concept |

| 6 | Nontheistic Options |

| 7 | The Nontheistic Religion of Buddhism |

| 8 | Cross-Cultural Sampler, Part 1 |

| 9 | Cross-Cultural Sampler, Part 2 |

| 10 | Find Your Sacred Space |

| 11 | Rites of Power, Presence, and Passage |

| 12 | Declarative Prayer |

| 13 | Lectio Divina |

| 14 | Centering |

| 15 | A Golden Key for Private Franklin |

| 16 | Meditative Exploration and One-Person Rituals |

| 17 | Final Thoughts for an Endless Journey |

Benediction

Selected Bibliography

Endnotes

Appendix

Acknowledgements

About the Author

At a time when religious perspectives in America as well as much of the rest of the world are disagreeing, sometimes violently, The Many Faces of Prayer offers a path to harmony and mutual respect among all spiritual paths. Rev. Dr. Thomas Shepherd has explored the fascinating subject of prayer in a way that promotes understanding, appreciation, and reverence for the rich diversity of beliefs about and practices of prayer that humankind has evolved. Readers of The Many Faces of Prayer will very likely come away not only with a new appreciation of the prayer traditions of other spiritual movements, but also with a greater appreciation of and enthusiasm for the prayer practices of the spiritual tradition they follow themselves.

Helicopter pilot in Vietnam, divinity student, career military chaplain, middle-school teacher, pastor, author, broadcaster, and seminary professor, Tom Shepherd has worked professionally in all of these areas and has built a strong marriage and family at the same time. Here is a man whose life has been anything but dull!

Spiritually inquisitive from childhood, Dr. Tom shares insights from the many paths he has explored, among them the Reformed Protestant tradition, the United Church of Christ, the Baha’i Faith, and Unitarian Universalism, settling into Unity as his home base more than 30 years ago. Tom is no stranger to Eastern spirituality. He’s been honored as a friend and colleague by the Venerable Bhante Y. Wimala, traveling Buddhist monk and Chief Sangha Nayaka (Head Monk) to the United States from Sri Lanka.

The rich diversity of his religious experience, training, and background has given Tom extraordinary insight into the beauty and the deep spiritual meaning of prayer traditions. In The Many Faces of Prayer, he writes with respect and affection for all of the paths he has followed. Perhaps these words from the preface best capture the spirit of The Many Faces of Prayer:

This book is not about the right way to pray; it’s about the ways people pray, what they pray to, and what they pray for. One of the principles guiding my work in the theology of spiritual practice is that the discussion should never be about what is correct and incorrect in prayer and spirituality. Let me be clear: A yawning chasm separates, “You got it wrong,” from “I see it differently.” To my knowledge, no one has been appointed the prayer police. How to approach God—or whatever you call the content of your pantheon—is a metaphysical question with deeply personal implications … You get to choose.

The Many Faces of Prayer guides the reader through a concise and very readable history of the God concept, beginning with the concept’s prehistorical roots, and looking at the sometimes very different ways evolving cultures have conceived of Ultimate Reality—including what Shepherd calls “nontheistic options.” More than other books on prayer I’ve discovered, The Many Faces of Prayer offers a comprehensive look at prayer and its meaning.

Perhaps the most significant question Tom Shepherd addresses here is what he calls the “Let It In/Let It Out Controversy.” Dr. Tom asks:

What’s unique about Tom Shepherd’s approach to the question is his very obvious respect for both perspectives. Perhaps recalling Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Shepherd seeks to understand before seeking to be understood. The Many Faces of Prayer will help readers from many spiritual paths grow in understanding of the sometimes very different paths their brothers and sisters follow. Perhaps this significant and readable work will inspire some who had abandoned spirituality to take up a spiritual path of their own.

Tom Thorpe, M.A.R.

Unity Village, Missouri

The work you are about to read flows from a lifelong interest in cross-cultural spirituality and ritual. As I think back over the decades, everything seemed so simple early in life. There was home, school, and church. Everyone sang the same music. Hosanna, Jesus loves me, pass the Lebanon bologna. Life was simple, until my curiosity drew me outside the cozy circle of familiarity, past a point where I began to hear the different drummers.

As a Baby Boomer growing up in a row house of an ethnically homogenous Protestant neighborhood in Reading, Pennsylvania, I was fortunate to attend Thirteenth and Union Elementary School. Not exactly diverse by today’s standards—we had one African-American student—nevertheless, the school had a significant minority of Jewish and Catholic students. We were also blessed with vibrant faculties who exposed us to the new, postcolonial, post-World War II world. Albert Schweitzer, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. We never spoke of religions in the emerging new countries, but teachers shared an enthusiasm for a wide range of cultures, East and West. And the Jewish and Catholic students sitting around me in class represented alien worlds to a Pennsylvania Dutch kid.

Sometimes a Jewish friend would invite me to the family Shabbat meal, where I donned a skullcap and listened to readings from the sacred text, previously known to me only as the “Old” Testament. It began to occur to me that people I cared deeply about—my friends and classmates—included those who saw the world quite differently than it had been presented to me at Zion’s Reformed Church. The struggle to make sense of life always presented a spiritual dimension to me, yet here were young people who didn’t believe in Jesus, and others who said they were Christians but prayed in the presence of full-sized idols. Where in the Bible did Jesus’ mom get promoted to some kind of goddess? My friends, not just marching to a different drummer, but worshipping a different deity? Wasn’t that the very definition of sin?

I loved and respected my elders at Zion’s—which was a kindly place full of Townhouse Crackers and Bible stories, and nothing approaching judgment. We never spoke of hell at Zion’s Reformed Church, because that was for bad people and we didn’t know anybody like that. Oh, sure. Hell was still on the books—like a law against emptying your bedpan from a second-story window—but it just didn’t apply. And these un-Protestant kids were my friends who just happened to believe differently. There was also my crabby, agnostic Uncle Gibb, who sneered at religion. Uncle Gibb knew I loved going to church, so he gleefully repeated the urban legend about Russian Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin saying he had found no God up there in 1961 when he orbited the earth.

So many differences of opinion on religion. I suppose that’s when I discovered I had become a universalist, even before moving away from childhood to travel the world. Travel doesn’t just broaden—it deepens. I encountered ever more diversity—Baha’is, Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, an endless array of spiritual traditions that by comparison made Jews and Catholics seem like coreligionists to a woefully ignorant Protestant like me.

The common theme I began to discover in spirituality and prayer was the need to make sense out of life and live it successfully. Different groups understood differently what “live it successfully” meant, but the impetus for a balanced, meaningful life flows horizontally through all the cultures of humanity and reflects in the religions we create to meet those needs. The central theme of this book is that humans do not share the same answers; we share the same questions, which we have answered differently.

As a theologian and teacher of graduate students, I tend to look at the questions through an analytic, cross-cultural lens, but after four decades in ministry, the residual pastor within me still loves and appreciates the practical aspects of human spirituality. My goal in writing The Many Faces of Prayer was to present a multicultural look at prayer, meditation, and ritual that addresses both the intellectual and devotional sides of the topic. Obviously, with a world of religious traditions to draw upon, this study cannot pretend to be exhaustive. Behind each door leading to a major faith group is another room full of doors, each with corridors full of subgroups, denominations, and geo-cultural practices.

Full Disclosure: Tossed Salad

Any serious study of world religions is likely to demonstrate that humans have evolved different answers to similar questions. The Many Faces of Prayer examines alternative points of view on prayer and attempts to be objective and even-handed. However, social, historical, and theological connections link every human worldview to a living culture. As a matter of full disclosure, let me place my theological cookbook face-up on the table: This study proceeds from an understanding of prayer as a tossed salad of communication and reflection. For me, prayer is communion with the divine—One Presence/One Power—in both the inner and the outer dimensions of life. To comply more completely with this goal of intellectual candor, I have offered a personal summary of belief, “Affirmation of Inclusive Christianity in a Multifaith World,” posted as an Appendix. As a theologian, I reserve the right to modify everything as new thoughts break through. Certainly the dialogue will continue, as each new generation wrestles with the questions of life and faith.

The fun part begins when we explore new sources of nourishment. What other banquets have humans cooked up for their daily spiritual fare? How can we incorporate touches of the wide diversity of world religious traditions to add color and flavor in our devotional diet? Cross-cultural prayer, meditation, and ritual practices offer a large choice of recipes for new, tasty dishes, adding zest to our spiritual cuisine. The café of world spiritual practices requires no reservations. Save your fork and spoon—dessert courses will be offered.

See you there.

Invocation

Father Almighty! We bow before Thine infinite goodness, and invoke in prayer Thine all-merciful presence of love.

We ask, and as we ask we give thanks that Thy power and presence are here in love and that we are tightly held in Thine all-embracing arms, where our every need is supplied and where we shall ever rest secure from all the buffets of the world.

Open to us the inner chambers of peace and harmony, which divinely belong to us as Thy children.

We come as little children into the sacred and trustful presence of Thy love, knowing full well that only love can draw and hold us in peace and harmony and prosperity.

Every fear falls away as we enter into Thee and Thy glory of love and as we bask in the sunshine of love, Thy love, Thy never-failing love! 1

—Charles and Cora Fillmore, Teach Us to Pray

PART

ONE

“Lift up your hands to the holy place, and bless the LORD.”

Psalm 134:2

The greatest threat to civility—and ultimately to civilization—is an excess of certitude. The world is much menaced just now by people who think that the world and their duties in it are clear and simple … It has been well said that the spirit of liberty is the spirit of not being too sure that you are right. One way to immunize ourselves against misplaced certitude is to contemplate—even to savor—the unfathomable strangeness of everything, including ourselves.1

—George F. Will

“The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit.”2

—Wade Davis

It is a simple act—to kneel, sit, or stand in prayer. Billions of people do it every day, observing a wide variety of culturally shaped habits. Prayer can be sounds or silence, thoughts or actions—floating flowers in the Ganges River or offering the body and blood of Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of Eucharist; contemplating the divine presence in the simplicity of the Quaker Meeting House or in the luxuriant Celestial Room of a Mormon Temple; Buddhist chanting to prepare the mind for meditation or Pentecostal Christians crying aloud in unknown tongues under the influence of the Holy Ghost.

Even a cursory glance at human religious experiences clearly indicates that spiritual practices always come with pre-existing conditions. Long before participating in daily devotions, people acquire a set of lenses that shape their experience, and the more effective the worldview, the less likely people will notice its effects. On a planet with thousands of languages and a vast multitude of cultures, intelligent life could hardly proceed otherwise. This very diversity of thought makes religious studies fascinating.

Back in the 1980s, when I was a U.S. Army Chaplain serving in Germany, I took a busload of soldiers on a weekend spiritual retreat to a guesthouse at Muggendorf, in the part of Bavaria known as Little Switzerland. The countryside was mountainous although not alpine, with architectural gems tucked here and there among the narrow valleys. One place we visited was a medium-sized basilica that rested like a house of solace under yellow, orange, and red trees.

Opening the door, I was struck with the interior size—larger than it appeared from the outside—and the wild proliferation of images. Through the centuries, European cathedrals provided a kind of religious education in stone and painting for illiterate peasants. Churches have been called the poor person’s Bible, because those who could not read the sacred text could see it illustrated all around them. Devout custodians of this sacred space had carried on the tradition; they crowded every alcove with statuary and decorated every flat space above the floor with frescoes about church history and Scripture. Sections of the floor offered more imagery through inlaid mosaics.

I sat on a hardwood pew and tried to focus on the artwork, but it was like listening for a lone voice in a riot. Even the altar overflowed with statues; gleaming golden spikes exploded from the heads of the apostles and the Virgin Mary. Instead of a worship experience, I felt besieged, bombarded by figurines and murals and picture-jammed stained glass windows.

When I looked at the soldiers, I noticed two distinct reactions. Some of the troops sat quietly. Their heads traveled back and forth, wall to ceiling to altar, like they were watching invisible angels playing handball across the vaulted sanctuary. None of them seemed to be praying. Meanwhile, other soldiers were kneeling in worship. I puzzled over the radically different responses until after we emerged from the church. As we waited for the bus, a Protestant soldier said, “Sir, I couldn’t pray in that place. It was packed with idols.” A few minutes later, a young Catholic woman in the group said, “Chaplain, wasn’t that wonderful?”

At that moment I totally and viscerally “got” an intellectual concept I had known for years. Worship needs vary greatly for people from different backgrounds. It isn’t right or wrong, it’s the lenses we wear. Spiritual needs are universal. Who hasn’t craved a quiet moment by oneself? But the takeaway lesson my Protestant and Catholic soldiers taught me was that any spiritual practice must be organically right for you. As Jesus of Nazareth reportedly said:

Ask, and it will be given to you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you. For everyone who asks receives, and everyone who searches finds, and for everyone who knocks, the door will be opened.3

—Mt. 7:7

Consequently, this book is not about the right way to pray; it’s about the ways people pray, what they pray to, and what they pray for. One of the principles guiding my work in the theology of spiritual practice is the discussion should never be about what is correct and incorrect in prayer and spiritual practices. Let me be clear: A yawning chasm separates “You got it wrong” from “I see it differently.” To my knowledge, no one has been appointed the prayer police. How to approach God—or whatever you call the content of your pantheon—is a metaphysical question with deeply personal implications.

You get to choose.

Asking “Which religion is right?” is an adolescent distraction that adds nothing to the discussion. Besides, if pushed to answer candidly, even people who accept the maxim of truth in all religions would probably say, “Of course, personally I believe my religious faith is ‘right,’ or why would I be here and not there?” Trusting my belief system in no way requires denigration of differing views.

No one has the right to tell 1.5 billion Muslims they are wrong to pray to a single Almighty Being, Allah (God) the Merciful, the Compassionate; or tell 900 million Hindus they should not be worshipping at temples dedicated to many gods and goddesses; or tell 2.5 billion Christians their Jesus is not the Way to God; or call 400 million Buddhists mistaken when they encourage meditation rather than prayer, because they believe no Supreme Deity exists. Some people connect with neighbor and universe through a God or gods out there; others find the Divine strictly as Indwelling Spirit; still others find the Divine in both the inner and outer dimensions. Some seek salvation from eternal punishment and access to the joys of paradise or heaven; some pursue enlightenment and absorption into the Oneness; others look for nonbeing and release from the cycle of birth-death-rebirth; others hunger for blissful union with God.

You and I have our preferences—we might even think another path is a dead end, or possibly harmful—but all people have full membership in the club of humanity, and everyone may bring whatever belief system works for them to the interfaith table. The opposite attitude, intolerance of differences, too often has given people license to act with violence toward offensive points of view. As I write this book, Muslim extremists in Libya and Egypt have attacked the American embassies in those countries. At Benghazi, Libya, heavily armed attackers set fire to the compound, resulting in the death of U.S. ambassador to Libya Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. Libyan officials condemned the attackers in strong terms. Mobs in both Egypt and Libya were outraged by an Internet movie that was critical of Islam, although at this writing the lethal attack in Libya may have been executed by a band of terrorists who piggybacked their moves on the public outcry.4

Libya has seen more Muslim-on-Muslim attacks than assaults against infidels; for example, the bombing of Mosques by rival factions in the Islamic community. Arabic news service Al-Jazeera has condemned the lack of response by security forces when minority religious groups, like the Sufis, are attacked. Al-Jazeera says police lethargy undermines “the principle of plurality within unity in Libya and all emerging democratic transitions in the Arab Middle East.”5 It is noteworthy the key principle of tolerance which Al-Jazeera cites—“plurality within unity”—closely resembles the motto of the United States of America, E Pluribus Unum (“Out of Many, One,” or “Unity From Diversity”).

Unfortunately, scenes of religious violence have occurred with alarming regularity throughout human history, with players from various faith groups exchanging roles of victim and perpetrator. Christian crusaders boasted about God’s pleasure as they shed the blood of nonbelievers to wrest the Holy Land from Muslim hands; Buddhist and Shintoist pilots attacked Pearl Harbor and flew suicide missions against enemy vessels during World War II; a Hindu extremist killed Mohandas Gandhi. George F. Will’s comment, cited earlier, seems to apply here: “The greatest threat to civility—and ultimately to civilization—is an excess of certitude.”6 Surely the baseline for a civilized world must include tolerance of beliefs that individuals may find personally intolerable. Aggression in the Name of God wins no hearts, makes no friends, and was condemned by founders of all the world faiths.

Library Full of Doors

Assembling a sampler of representative studies worthy of this book’s subtitle, How the Human Family Meets Its Spiritual Needs, requires hard choices leading to sins of omission, an occupational hazard for theologians. Teaching world religions at Unity Institute® and Seminary often feels like leading students into a vast library full of doors. Each portal represents a major faith group: Baha’i, Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Islam, Jainism, Judaism, Hinduism, Neo-paganism, Shinto, Sikhism, Tribal-Indigenous Religions, Voodoo, Zoroastrianism—an endless parade of faiths and practices.

Step inside and what do you find? Another room of doors! Each new doorway leads to antechambers of subgroups, denominations, and schisms of the faith marked on the outer entrance. The floor upon which we stand merely represents religious traditions today. Think about the levels below and above, the history and potential of each faith.

Open the Christian door, for example. Inside you will find another hall with doors leading everywhere—from the snake-handling euphoria of extreme Pentecostalism to majestic rhythms of incense-cloaked Russian Orthodox worship; Quaker Silent Meeting to boisterous melodies of African-American Baptist churches. In what bizarre chemistry of faith does a Lutheran and a Jehovah’s Witness share common DNA? Yet they all claim to be Christians. Who is qualified to say they are not? Every Christian group traces its family tree back to Jesus Christ and the disciples, but that was apparently the last time we all belonged to the same household. Some find this lack of continuity disturbing. For example, take the following quote from a website of a conservative church in Pennsylvania:

The New Testament condemns religious division. Christ prayed for the unity of his disciples (John 11) so that the world might believe the Father had sent him into the world. Religious division (denominationalism) is contrary to his will and defeats his purpose.7

Others consider the subdivisions in religious thinking as natural, even healthy. Certainly, as best-selling author and biblical scholar Bart Ehrman has demonstrated in his book Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, Christianity has never been monolithic. Variability in doctrine and ritual dates to the period immediately after the death of Jesus. Some of the differences were so extreme that modern Christians often have difficulty accepting the variations that did not prevail as a legitimate part of the historic Church.

The wide diversity of early Christianity may be seen above all in the theological beliefs embraced by people who understood themselves to be followers of Jesus. In the second and third centuries there were, of course, Christians who believed in one God. But there were others who insisted that there were two. Some said there were 30. Others claimed there were 365 … there were Christians who believed that Jesus’ death brought about the salvation of the world. There were other Christians who thought that Jesus’ death had nothing to do with the salvation of the world. There were yet other Christians who said that Jesus never died.8

Multiplicity in thought and practice exists in every religious tradition on Earth, but Christianity in the United States has taken the art of diversity to a new zenith. American denominationalism is the new orthodoxy.

The practice of denominationalism came into being in the 18th century during the Evangelical Revival, but the idea started with the Puritans. The whole idea of denominationalism is a reaction to sectarianism. Sectarianism is exclusive, meaning that each sect of a religion believes that its way is the right way and that no other way is acceptable. Denominationalism as a concept is more inclusive, because it espouses that one particular Christian group is really just a part of a bigger religious community—the Christian Church. Denominationalism means that each subgroup is accepted and acknowledged, and no one group can represent the entirety of Christianity.9

Gathering as equals who are not the same, we can learn from one another by beginning with words like, “Here’s what works for me …” then listening with an open mind as they reciprocate. We do not need to agree on theology to get along. Besides, that will not happen in this lifetime—probably not in the lifetime of our species. We do need to disagree agreeably, which is a basic ingredient for peace in a pluralistic world.

What Am I Doing in Prayer?

Without aiming to agree on everything, let’s begin our look at The Many Faces of Prayer with the most basic question: What am I doing in prayer? More specifically, to Whom (or what) am I praying? The power of the mountain, a river god, an honored ancestor, the Patron Saint of Editors (there is one—St. John Bosco10), or the solitary Creator of the cosmos, or maybe the divinity within me? Am I communicating with a Presence and Power beyond myself—engaging in an I-Thou relationship with my Higher Power—or reflecting upon something deep in my consciousness? Can prayer be both, or neither? What kind of link could exist between my apparently limited lifespan and the divine? For that matter, what is the divine anyway? How does my cultural worldview, which I inherited at birth, affect my method of prayer?

All of the following rhetorical questions represent religious worldviews currently held by religious traditions on this planet:

Culture, history, geography, and longstanding tradition powerfully shape every child’s worldview. Slightly different shades of belief bring significantly different results. A Roman Catholic monotheist might pray to a Saint or the Blessed Virgin Mary, which a Baptist or Methodist monotheist is not likely to do. Muslims pray facing Mecca; Mormons do not. Many Hindus believe in reincarnation and a multitude of gods and goddesses; many Buddhists believe in reincarnation and no god whatsoever.

When children grow to adulthood, they will sometimes reject the religious tradition in which they were born. Dalton Roberts—multitalented poet, philosopher, teacher, musician, songwriter, author, newspaper columnist, and formerly the highest elected official in Chattanooga, Tennessee—took this thought to its logical conclusion in his weekly Sunday Journal column:

After my early disenchantment with religion, I went through years of trying to not believe. I don’t just mean to not believe in religion, but to not believe in anything so I could make sure I had an open mind. Yet all the time my thinking was leading me to make decisions on what I was thinking. Self-honesty finally made me see that I was always believing in something—tarot cards, fate, luck, the law of averages, science—you name it. I came to see it is as impossible to not believe as it is not to think.11

Even disbelief comes with a hidden program running in the background. Some children, especially in Western Europe and North America today, are raised in homes without any formal religious affiliation. However, dominant religio-ethical themes provide a cultural context in our secular world, whether people are churchgoers or not. When American or British atheists reject God, they are not usually rejecting the Hindu Preserver Vishnu, the M ori god of the sea Tangaroa, or the African storm god Shango. Even Satanists rely upon Jewish, Christian, and Muslim mythologies for the main characters in their anti-pantheon. An urban legend illustrates this point. During the Protestant-Catholic disturbances in Northern Ireland of the mid-20th century, a young man approaches a barricaded checkpoint and is halted by the guard.

ori god of the sea Tangaroa, or the African storm god Shango. Even Satanists rely upon Jewish, Christian, and Muslim mythologies for the main characters in their anti-pantheon. An urban legend illustrates this point. During the Protestant-Catholic disturbances in Northern Ireland of the mid-20th century, a young man approaches a barricaded checkpoint and is halted by the guard.

“Catholic or Protestant?” the sentry demands.

“Atheist,” the stranger replies cockily.

The guard is not impressed. “Catholic atheist or Protestant atheist?”12

Preset categories of thought shape the world and influence us even when we categorically deny their existence. We grope in the dark to find answers, yet it is the questions that elude them. Those who forsake Christianity seldom abandon Jesus’ ethical mandate to love our neighbor as ourselves, return not evil with evil, treat neighbors and strangers with equal respect, show kindness to the poor and afflicted and gentleness toward children, and work for justice and equality for all people. The more we reflect on this “simple act” of prayer, the more we realize the complex assumptions and embedded theologies we bring to the process of seeking—or rejecting—communion with the divine.

Anyone who has studied the religions of humanity knows our species has displayed a high degree of creativity in meeting its spiritual needs. In his 1966 book, Religion: An Anthropological View, Anthony F.C. Wallace noted, “Even the so-called ‘monotheistic’ religions invariably include an elaborate pantheon.” Wallace went on to list the supernatural beings in the complex mix of historic religion and pop culture of the small American town in which he grew up. The list hit all the players—God, Jesus, the Devil, Saints, and on to minor Judeo-Christian characters—then continued with less obviously “religious” but clearly present supernatural entities—ghosts, souls in some kind of afterlife, witches, Santa Claus, and fairies, plus depersonalized supernatural forces such as superstitions. Wallace added, “Not everyone ‘believed in’ all of these supernatural beings, at least not all at the same time …” But the network of supernatural and supersensory phenomenon that constitutes a pantheon is much more extensive than most people credit.13

Other observations from the social sciences can help make sense of the complex world of religious traditions. When surveying unfamiliar territory in cross-cultural prayer studies, looking through the lens of a social science tool known as cultural relativism can help chart the way.

Cultural Relativism

Cultural Relativism is the view that moral or ethical systems, which vary from culture to culture, are all equally valid and no one system is really “better” than any other. This is based on the idea that there is no ultimate standard of good or evil, so every judgment about right and wrong is a product of society. Therefore, any opinion on morality or ethics is subject to the cultural perspective of each person. Ultimately, this means that no moral or ethical system can be considered the “best,” or “worst,” and no particular moral or ethical position can actually be considered “right” or “wrong.”14

The religions of humanity represent an array of beliefs and practices, some quite simple, others highly complex. Although diversity of thought is unavoidable, undue emphasis on the differences among the faiths has led to mutual excommunications, crusades, holy wars, and acts of genocide, as the critics of “organized religion” have rightly observed. The history of bigotry-based violence has driven some progressive thinkers to declare parity among world religions, summarized by a charming ditty from the Baha’i Faith:

God is one, man is one

And all the religions are one.

Land and sea, hill and valley

Under the beautiful sun.

God is one; man is one

And all the religions agree.

When everyone learns the three one-nesses

We’ll have world unity.15

It is politically correct, especially among today’s Cultural Creatives, to identify points of unity and avoid mentioning the disagreements. Certainly, affable relations between faith groups require mutual respect, but there is a vast difference between accepting the principle of cultural relativism—which proclaims all truth is local—and declaring all religions proclaim the same message.16 They clearly do not, and never have. Teachers of the great faiths usually addressed specific issues endemic to their times and places. They were not abstract philosophers but practical leaders who solved existential problems and answered the everyday questions of a living community. When their successors continued the faith, they adapted its ideas and practices to new circumstances.

These differences cannot be ignored without discounting the unique contributions of all communities of faith. To affirm cultural relativism—all religions are equal—is not the same as pronouncing all religions the same. There are genuine differences in the way human communities have answered basic questions about Ultimate Concerns: life, death, eternity, and humanity’s place in the Cosmos. To lump all religious traditions into one amorphous “Interfaith” heap only denigrates the rich diversity of world faiths. We come to the interfaith table as members of a culture. Dialogue begins when we recognize that theological differences have as much to teach us as similarities do.

I recall the first time this idea dawned on me. It was the 1960s, during the hot days of the Civil Rights movement in the United States. I was a young soldier living in the barracks with men from all sorts of ethnic and religious backgrounds. During our many late-night, solve-the-world’s-problems marathon discussions, one of my favorite contributions was to declare all people are the same, regardless of race. Although my liberal-sounding platitude usually went unchallenged, one evening an African-American soldier surprised me by disagreeing.

“No, Tom. We are not all the same,” he said. “I’m not just a dark white guy. We’re different, and it makes life more interesting.”

It was another aha moment. Differences add, not subtract. Flower gardens need variety. In the garden of humanity, diversity in religion or ethnicity or race enhances life.

Who knows what concepts remain a mystery because of the lenses we wear, or perhaps the sounds we can’t hear? Cetaceans, a group of highly intelligent marine mammals that includes dolphins and whales, communicate through complex sounds that some researchers think is language. Humpback whales sing recognizable melodies across vast stretches of sea, and their tune changes every year.

At this writing, scientists have no idea how whales in the warm waters near Mexico receive the same new music as other humpbacks swimming the cold North Pacific, or why humpbacks in different ocean basins sing different songs, even though all the whale communities update their melodies annually. The vocalizations appear to be related to mating behavior, but does the language of whale love also contain spiritual dimensions?17

Differences in human spiritual behavior are easier to track. For example, take Islam and Hinduism. Although they often share geographic boundaries and live in enclaves within each other’s territory, Muslims and Hindus sing a different tune religiously. They share no harmony about the number of gods that may be worshipped; they disagree about the number of lives an individual may live along the path to spiritual mastery; they stand at odds over the number of sexual practices blessed by the divine; and they differ about the proper menu of dietary taboos. Nor are the differences trivial: Hindus pray in temples adorned with hundreds of idols; Muslims condemn idolatry as grievous sin. To declare these two religions in harmonious agreement is only possible if one has never encountered a Muslim or a Hindu.

Critical thinking about spiritual practice clears the underbrush and asks, “What is actually happening here? What are religionists really saying? What points of similarity-dissimilarity are present?” Metaphysical theology loses its credibility when it succumbs to the New Age fantasy of “all religions are the same” and attempts to homogenize ideas that are contradictory and unmixable. To comprehend Hinduism or Islam clearly—finding some points in common, others wholly incompatible—is far better than trying to make a hybrid from two very different worldviews, which does a disservice to both. To understand this dynamic better, look at ecological studies.

The natural world energetically produces creatures that simultaneously cooperate and compete. Predator and prey need each other for a balanced ecosystem to endure; insects and carrion eaters clean up the leftovers, and the grass and other plants absorb nutriments through the soil when all the mobile critters stop moving at the end of their lives. Human systems of thought are also competitive and cooperative. Religions occupy a niche in all sociocultural systems and have an important contribution to make to the health and well-being of humanity, but their specific contributions will vary with the cultural environment.

Dueling Dualisms

The question about whether effective prayer can be dualistic or not seems to underlie much of the recent hullabaloo about prayer in Metaphysical Christianity. Speakers and authors often wrestle with the demon of dualism and attempt to exorcise it from their ministry and spiritual life. I have heard seminary students fret about praying in public, because they feared someone might criticize them for “praying dualistically.”

Some of the confusion comes from the fact the word dualism, like spiritual or metaphysical, is a technical term philosophers and theologians use differently from the generic way it is used by ordinary religionists. Dualism signifies opposites—for example, Yin and Yang, male and female, good and evil, truth and error, divine and human, God and the Devil. Note that not all opposites are at war. Yin-Yang, male-female, divine-human can be held in creative tension to form a greater whole. However, any sort of separating difference can technically be called dualistic. Communication between conscious minds implies dualism; you speak, and I receive your ideas through sound waves and language. Conversation, dialogue, or even talking to oneself can arguably be called dualistic.

Dualism contrasts with monism, which is the theory that there is only one fundamental kind, category of thing or principle; and, rather less commonly, with pluralism, which is the view that there are many kinds or categories. In the philosophy of mind, dualism is the theory that the mental and the physical—or mind and body or mind and brain—are, in some sense, radically different kinds of things.18

The polar opposite of dualism is monism, which maintains diversity is at best an error-belief, because the All is indivisibly One. Since we experience the world as separated—many people, places, and events—the dance of dualism is much easier to perform than Monism, which requires a little fancy footwork. Sometimes those who hold to cosmic monism attempt to explain the variety in everyday experience by speculating about two realms—an ideal, eternal, changeless world versus the ephemeral plane of human existence, the Absolute and the relative. Some scholars find monism within the ancient Ved nta school of Hinduism in the East, although others hold the Vedic works contain both dualistic and monistic elements.19

nta school of Hinduism in the East, although others hold the Vedic works contain both dualistic and monistic elements.19

Western expressions of monism go back at least to Platonic idealism of the fifth century BCE. Plato held the real world was an ideal realm of perfect forms; the everyday world was no more than a shadow on the wall by comparison. However, Plato’s star pupil, Aristotle, repudiated his mentor and said all we have is the everyday world. The ideal realm of perfection is an illusion based on the concrete world we see, not the other way around.

Beyond metaphysical considerations, there are ethical dimensions to the dualism-monism discussion. Some monists denigrate the manifest world as temporary, shallow, unreal existence. For its shadowy brevity, they substitute visionary hopes for an ascension to or absorption in the eternal Absolute through spiritual and mental disciplines. While such a grand vision can help individuals cope with life, it can also trivialize human suffering and place all hope on a world of ideal existence rather than working to solve problems in the only world we know firsthand. Not surprisingly, the argument between dualists and monists over what constitutes Ultimate Reality continues to this day.

Prayer: Communication or Reflection?

Every practice humans identify as prayer seems to fall into one of two categories, and the way a religious faith answers this question is in some ways more important than the shape of its God concept. Either we are addressing some kind of spiritual reality beyond ourselves, or we are contemplating the spiritual essence that dwells within us. While researching this work, the only variation I discovered was among those who attempt to do both—to see prayer as communication with God in the cosmos, and also as reflection upon their Indwelling Divinity—which might be a third option, provided we avoid playing linguistic mind games. More about that later.

What premises underlie the acts of prayer to God as opposed to prayer as God?

Most religionists in Western traditions address their prayers to a Supreme Being, to Saints, the Virgin Mary, or to some kind of benign external Power. Prayer for them is definitely communication, albeit in many different forms. They pray to God. Other traditions, more commonly found in Asia but also in the West, see themselves as expressions of the divine, and view prayer as reflection.

Sometimes reflective prayer (exploring spiritual thoughts) is hard to distinguish from meditation (listening, or seeking stillness beyond words). Prayer as reflection can involve communion with Indwelling Divinity, God-self, Christ-within, the Buddha-nature, or the I AM, which many believe is the true identity of every sentient being. Reflective prayer can be in stillness, the Silence, or by use of affirmations and Centering. The first three verses of the 23rd Psalm, perhaps the best-known spiritual reading in the Bible, are not addressed to an external deity but represent straightforward affirmations by which the psalmist reflects on the power of God.

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures;

he leads me beside still waters;

he restores my soul.

He leads me in right paths

for his name’s sake.20

If this is prayer, to whom is it addressed? The psalmist seems to be talking to himself about his belief in Divine Providence. Even verses 4-6, which ostensibly speak to God, are neither supplication nor thanksgiving but second person declarations, as if the psalmist is reminding himself what is true.

Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil;

for you are with me;

your rod and your staff—

they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord

my whole life long.21

The 23rd Psalm is undoubtedly prayer, but it’s a better example of prayer as reflection rather than communication. The psalmist is not talking to a Supernatural Being; he appears to be talking to himself about the God of Israel. Historically speaking, the author of the Shepherd Psalm was not ready to evict Yahweh from His throne in the clouds or His Mercy Seat inside the veiled holy of holies in the Jerusalem Temple. Reflective prayer for the psalmist probably meant an inward consideration about outer realities, not yet an attempt to become one with an indwelling divine nature. That concept would come later in Jewish and Christian mysticism.

Yet the prayer mostly recounts what the psalmist already knew about God, rather than telling God what He (Yahweh was male) knew about Himself. Even when shifting from third person (“He makes me lie down in green pastures …”) to second person (“You anoint my head with oil …”), the psalmist continues to reflect on God’s mighty deeds rather than convey new requests and wait for a response, which defines genuine communication.

Letters to God

Elements of a maximum-inclusive definition for prayer have sometimes appeared in the writings of mystical theologians like Charles Fillmore. For example, this passage from Atom-Smashing Power of Mind:

… prayer is the opening of communication between the mind of man and the mind of God. Prayer is the exercise of faith in the presence and power of the unseen God. Supplication, faith, meditation, silence, concentration, are mental attitudes that enter into and form part of prayer. When one understands the spiritual character of God and adjusts himself mentally to the omnipresent God-Mind, he has begun to pray aright.22

It is obvious Mr. Fillmore was attempting to allow for prayer as both communication and reflection. His writings are full of examples of speaking to God; other times, he reflects on the Divine-within. Myrtle Fillmore frequently sounds even more traditional in her published works. The following passage from Myrtle Fillmore’s Healing Letters suggests she did not fear appearing dualistic.

Prayer, as Jesus Christ understood and used it, is communion with God; the communion of the child with his or her Father; the splendid confidential talks of the son or daughter with the Father. This communion is an attitude of mind and heart … Sometimes I have written a letter to God when I have wanted to be sure that something would have divine consideration and love and attention. I have written the letter, and laid it away, in the assurance that the eyes of the loving and all-wise Father were seeing my letter and knowing my heart and working to find ways to bless me and help me to grow.23

Mrs. Fillmore was very clear that prayer, for her, involved direct “communion with God,” which she described as a talk between daughter and Father. She wrote letters to God to be sure her Father got the message. This is not just looking to God-within; Mrs. Fillmore reached out to God with her mind and felt a powerful I-Thou connection.

Even before the Fillmores became husband and wife, Myrtle made certain Charles understood she would follow her own guidance on theological issues. In a letter dated September 1, 1878, she writes to her future spouse:

You question my orthodoxy? Well, if I were called upon to write out my creed it would be rather a strange mixture. I am decidedly eclectic in my theology—is it not my right to be? Over all is a grand idea of God, but full of love and mercy.24