TITLE

Copyright

PREFACE

1. EARTHWORM

2. VERMICULTURE

3. VERMICOMPOST AND VERMIWASH

4. ROLE OF VERMICOMPOST IN PLANT GROWTH

5. STANDARDS OF HIGH-QUALITY VERMICULTURE PRODUCTS

6. VERMICULTURE FOR WASTE REDUCTION

GLOSSARY

VERMITECHNOLOGY

A. Mary Violet Christy

ISBN: 9788180942525

All rights reserved

Copyright: MJP Publishers, 2014

Publisher: C Janarthanan

MJP Publishers

5 Muthukalathy street

Triplicane

Chennai 600005

Tamilnadu

India

Branches: New Delhi, Tirunelveli

This book is published in good faith that the work of the author is original. All efforts have been taken to make the material error-free. However, the author and publisher disclaim the responsibility for any in advertent errors

PREFACE

Vermitechnology involves the artificial rearing of earthworms and using them for the production of vermicompost, which is anutrient-rich material that can be used as a fertilizer. In the process, earthworms degrade organic waste material into a useful product. This book contains the basic concepts of vermicomposting written in a simple and lucid manner and isorganized in six chapters. The first chapter deals with fundamentals of earthworms. The second chapter discusses the culture of earthworms, i.e.,vermiculture. The third chapter describes in detail the different methods of production of vermicompost. Chapter four discusses the role of vermicompost in plant growth and the application ofvermicompost to plants. The fifth chapter deals with the details of converting vermicompost into a marketable product. The sixthchapter discusses how vermicompost can be used for organicwaste reduction. I am grateful to Dr. M. Karunanithi, Chairman, VivekanandhaEducational Institutions, and Dr. Devatha, Principal, andDr. Vivekanandhan, Bioscience Director, Vivekanandha Collegeof Arts and Science for Women, Tiruchengode, for stimulatingand encouraging me to write this book.I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Mr. Peter,Librarian, Thanthai Hans Roever College, Perambalur, for makinguseful suggestions, which helped me in composing this book.

I feel a deep sense of gratitude to my husband Mr. K. Sekarfor his suggestions and encouragement and to my daughterS. Harini for her love and the much-needed happiness whichshe has brought into my life.I owe my gratitude to my beloved parents R. Arpudasamyand A. Susaimary, my father-in-law, A. Krishnan, mother-in-law, K. Pitchaiammal, my brothers, A. Anand Arockia Raj,A. Vinci and A. Rex Irudaya Raj, and A. Josphine Mangala Mary,for their kind cooperation, which helped me complete this book.I am also thankful to MJP Publishers especially Mr. J.C. Pillai,Publisher, Mr. C. Sajeesh Kumar, Managing Editor and P.ParvathRadha, Project Coordinator, for taking keen interest in bringingout this book in its present form.

A. Mary Violet Christy

1

EARTHWORM

INTRODUCTION

The earthworms are a group of invertebrates belonging to the Phylum Annelida and Class Oligochaeta and represented by more than 1000 species. Earthworm is nocturnal and the movement is effected by the alternate contraction and relaxation of circular and longitudinal muscles. The soil particles swallowed with the food probably help in the grinding operation called mechanical digestion, since it facilitates the subsequent action of the digestive enzymes. Earthworm is a free organism and it is present in moist and dark places in mud. It respires aerobically and lacks specialized respiratory organs. It has a moist skin that serves this purpose. Earthworms are of great economic value to mankind because they improve the soil quality by their action.

Annelids are segmented worms, with each segment bearing the same fundamental structures as all the others, though minor differences can occur between some segments. By distributing organs among many segments, it becomes less dangerous to an annelid if one organ is damaged. Annelids usually add new segments as they grow older by simply making new copies of the body’s last segment, a sort of efficient assembly-line construction. In annelids, blood circulates in a closed system of blood vessels; it does not at some point simply drain into open sinuses, as with the molluscs. This assures that the annelid’s blood does not pool in some place in its body and for a time become useless, and that only oxygen-depleted blood is circulated back to have its oxygen replenished. Annelids are covered with a very thin, cellophanelike cuticle, which cuts down on moisture loss from the body. Annelids do not dry out as fast as molluscs.

Figure 1—Earthworms

CATEGORIES OF EARTHWORMS

The most common earthworms in North America, Europe, and Western Asia belong to the family Lumbricidae, which has about 220 species (Figure 1.1). Earthworms ingest organic material and facilitate the redistribution of crop residues and organic matter throughout the soil profile (Timothy et al., 1999). Earthworms range from a few millimetres to over 3 feet long, but most common species are a few inches in length. Only a few types are of interest to the commercial earthworm grower, and of these only two are raised on a large-scale commercial basis. In the Indian subcontinent earthworms are represented by 509 species in 67 genera under 10 families (Julka, 1993). There are more than 4400 distinct species of earthworms, each with unique physical and behavioural characteristics that distinguish them from one another. Based on the morphological nature and ecological strategies, earthworms have been classified into three groups by Bouche (1977). They are anecic, endogeic, and epigeic, descriptive of the area of the natural soil environment in which they are found and defined to some degree by environmental requirements and behaviours.

Anecic Species

Anecic worms feed on decaying organic matter and are responsible for cycling huge volumes of organic surface debris into humus. Represented by the common nightcrawler (Lumbricus terrestris ), they build permanent vertical burrows that extend through the upper mineral soil layer, which can be as deep as 4–6 feet. These species coat their burrows with mucus that hardens to prevent collapse of the burrow, providing them a home to which they will always return and which they are able to reliably identify, even when surrounded by other worm burrows.

Endogeic Species

These species build extensive, largely horizontal burrow systems through all layers of the upper mineral soil. These worms rarely come to the surface, spending their lives deep in the soil where they feed on decayed organic matter and mineral soil particles. These worm species help to incorporate mineral matter into the topsoil layer as well as aerate and mix the soil through their movement and feeding habits, e.g. Pontoscolex corethrurus.

Epigeic Species

Represented by the common redworm (Eisenia fetida), these are found in the natural environment in the upper topsoil layer where they feed on decaying organic matter. Epigeic worms build no permanent burrows, preferring the loose topsoil layer rich in organic matter to the deeper mineral soil environment. Epigeic worms are the only types that are used in vermicomposting and vermiculture systems.

CHARACTERISTICS OF EARTHWORMS

Colour

Commonly earthworms are pale pinkish in colour, replaced in front by dark brown which extends backwards as a mid-dorsal stripe. The hinder end is also brown in colour. The colour of the body is due to the porphyrinporphyrin present in the integumentintegument. The porphyrinporphyrin protects the worm from the injurious effect of bright light.

Habitat

Earthworms are nocturnalnocturnal terrestrial animalsterrestrial animals and live in burrows in the moist soil rich in dead organic matter, irrigated farmlands near the pools, ponds, rivers and gardens. They do not prefer very clayey, sandy, dry or acidic soils which are deficient in organic matterorganic matter. The burrow runs almost vertically into the earth up to 45 cm deep and is built with the help of skin gland secretions. In cold weather, dried leaves and soil close the opening of the burrow. If the body surface becomes dry, the worm will die. During rainy season the burrows get flooded with water, the worms come out on the surface. During summer season the worm becomes dry. They avoid strong light. If the worms get pain by undecomposed organic material and mechanical vibrations, they come quickly to the surface.

Body Structure

The first segment is called peristomiumperistomium. The next segment is prostomiumprostomium. Setae are the main locomotory structures found in all body segments except first segment, last segment and clitellumclitellum (Figure 1.2). It helps the earthworm for locomotionlocomotion.The muscles of the boy control the movement of the earthworm. Mature earthworms possess a thick belt of a smooth girdle of skin around the 14th and 15th segments, called the clitellum. Depending upon the presence of the clitellum, the developmental stage of the earthworm can be divided into three stages: the mature worms called post-clitellatepost-clitellate, the worms in the maturity-attaining stage called clitellateclitellate and immature (without clitellum) worms called pre-clitellatepre-clitellate. The clitellum is a glandular structure that has many gland cells, which secrete the egg or cocooncocoon. The last segment of the body is called anal segment that has a slitlike opening called anus.

Figure 1.2 Structure of earthworm

Locomotion

Though earthworms have no bones, their complex system of muscles enables them to not only wiggle crazily but also to very quickly alternate between being stubby and thick, and long and slender (Figure 1.3). Earthworms possess tiny, practically invisible bristlesinvisible bristles, called setaesetae, which usually are held inside their bodies. When the worms want to stay in their burrows, they jab their setae into the surrounding dirt, thus anchoring them in place. This comes in handy if a bird nabs a worm’s head and tries to pull the worm from its burrow (Figure 1.4). The setae anchor the worm so well that it may break before coming out. If a worm in its burrow wants to move forward, first, using its complex musculature, it makes itself long. Then it anchors the front of its body by sticking its front setae into the soil. Now t pulls its rear end forward, making itself short and thick. Once the rear end is in place, the front setae are withdrawn from the soil, but setae on the rear end are stuck out, anchoring the rear end. Now the front end is free to shoot forward in the burrow as the worm makes itself long and slender. Then the whole process is repeated.

![]()

Figure 1.3 Surface movement of earthworms

Figure 1.4 Burrowing movement of earthworms

Food Ingestion

The earthworm takes large amount of soil, dry leaves, grasses, algae, etc. from the earth. Earthworms prefer food material rich in nitrogen and sugar. The digestion is extracellularextracellular. The digestive fluid contains some proteolytic enzymes. Calcium is secreted by calciferous glands which probably neutralize the humic acid present in the soil. Proteins are hydrolysed into amino acids by proteolytic enzymes like trypsin and pepsin. The earthworm gut provides a suitable place for the growth of bacterial coloniesbacterial colonies and this is evidenced by the fact that earthworm castings contain significant number of bacteria, thereby increasing the number of bacteria that is present in the surrounding soil. The digested food material is passed out through the anus in the form of castings. EjectionEjection is effected by a circular contractioncontraction which starts at the anterior end of the rectum and progresses backwards. The castings are in the form of small rounded pelletspellets and balls.

Reproduction

Earthworms are heamaphroditichermaphroditic like snails and slugs, since each earthworm carries both male and female reproductive parts. First of all, not every earthworm segment bears sex organs. Counting from the front, the worm’s male sex cells lie in segments 10 and 11. From here the sperms pass through sperm ducts to two male genital openings at the bottom of segment 15. On segments 9 and 10 there are two minuscule sacs called sperm receptaclessperm receptacles, or pores, where during mating, sperms are deposited (Figure 1.5). However, this is not where eggs are produced. The egg-producing ovaries reside in segment 13, from which eggs are released through the female pores into egg sacs in segment 14. Finally, there’s a rubbery, arm-band-like thin belt covering the worm’s body from segments 14th and 5th, and this is called the clitellum.

Figure 1.5 Reproduction in earthworms

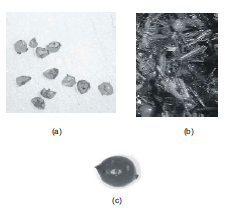

Figure 1.6 Shape of cocoons of (a)Eisenia hortensis, (b) Perionyx excavatus and (c) Lumbricus terrestris