Also by Lorraine Chittock

Shadows in the Sand —

Following the Forty Days Road (1996)

Cairo Cats — Egypt’s Enduring Legacy (1999)

Los Mutts — Latin American Dogs (2010)

Dogs Without Borders —

Tales and Tips from the Road (2011)

The Kenya Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals survives completely by donation. Please visit www.kspca-kenya.org to see how you can help.

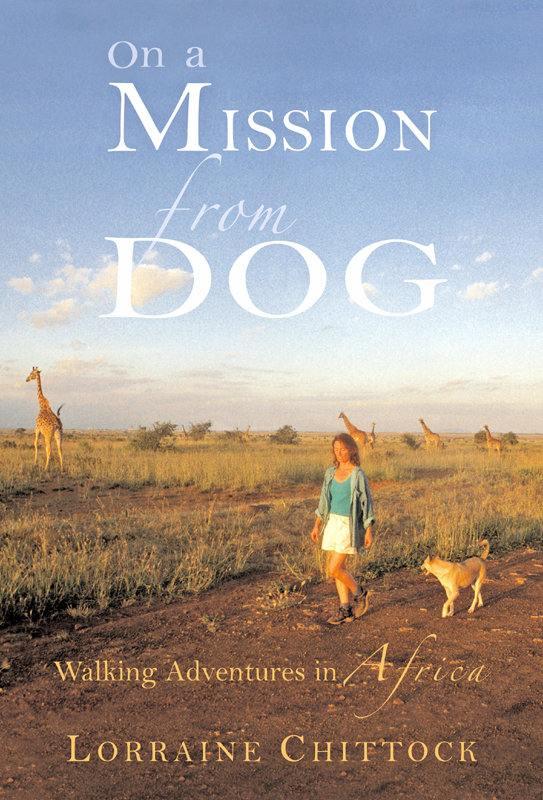

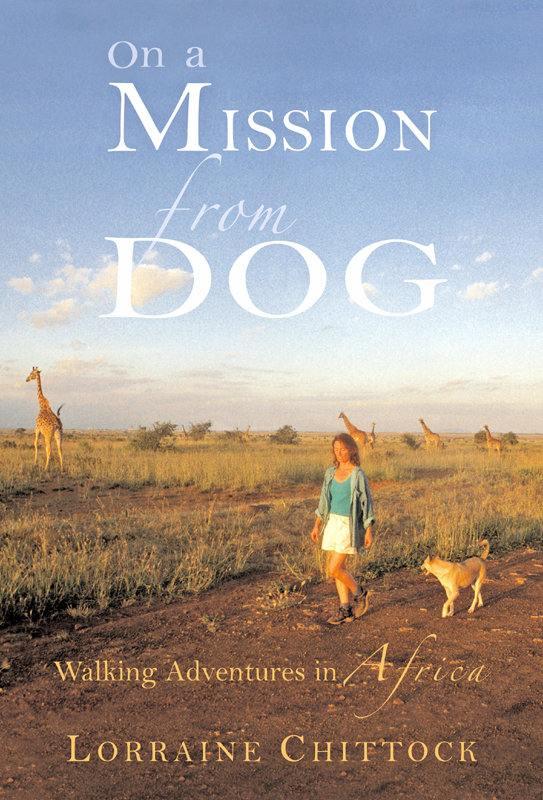

Front cover photograph © 2011 by John Dawson.

Back cover: top two photographs and bottom right side © 2011 by

John Dawson.

All others © 2011 by Lorraine Chittock.

On a Mission from Dog — Walking Adventures in Africa first published by Camel Caravan Press in 2011.

The audio version, read by the author, is available at: OnaMissionfromDog.com.

The publisher is grateful for permission to reproduce material. While every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders, the publisher would be pleased to hear from any not here acknowledged.

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, withour prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Camel Caravan Press

OnaMissionFromDog.com

LorraineChittock.com

ISBN 978-0-9826532-0-3

ISBN: 9780982653258

Printed by

Bay Area Green Printing

www.bayareagreenprinting.com

Acknowledgments

To my parents, Barbara Timms and Chris Chittock. I am so fortunate that your equally strong traits of animal lover and adventurer merged when creating me. Thank you for giving me the freedom as a child to experiment in areas traditionally considered both feminine and masculine—essential skills for the life I now lead.

Thank you John Dawson. The traits necessary for a successful relationship came far more naturally to you than I. Only recently am I able to fully appreciate the wisdom, generosity, humor and love you gave to our marriage. May our friendship endure. When I asked John if he’d like to read On a Mission from DOG before I sent it out into the world, he quoted a passage from a book on two long-distance runners, The Perfect Distance — Ovett and Coe: The Record-Breaking Rivalry. Author Pat Butcher states, ‘Total recall only happens in fiction. Forgetting and fabricating are not always intentional, as the debates over retrieved memory suggest.’

Numerous people courageously poured through early drafts of the manuscript and I give many thanks for your perseverance and encouragement. Three women proved invaluable and pivotal in the editing process. June Appel; for your astute psychological insight and wit while tackling some very challenging issues; Sandra Conant Strachan for your attention to detail; Sandra Courcelles for believing in the manuscript throughout.

Many thanks to Warguto Saless who was an invaluable translator while traveling in Northern Kenya. David Adolph and BJ Linquist-LaRoche were very helpful in clarifying Gabra traditions. Salome Nyambura and Theo Symes were invaluable for Kiswahili translations.

I’d like to especially thank Ronni Ann Roseman-Hall for using her special gifts to help find Bruiser not only when he was lost in Kenya, but years later in Costa Rica and Chile. Many thanks also to Suzanne Grandon for offering her valuable insights during those times.

The following people invited Dog, Bruiser and myself into their homes after leaving Kenya, giving me breathers from camping while I took my career on the road. Thank you for your company, generosity and interest in my life while providing a comforting atmosphere to write.

In California, Carol Kooi was a creative soul mate and artist on a similar spiritual path parallel to my own for over twenty years. You are greatly missed.

Jean Glendinning, England; Charlotte, Neil, Kathy & Dick Doughty, Texas; Karen Hilmy, New York; Susan and Alison Miller, Virginia; Linda and Morgan Lambert, California; Troy Snow, Utah; Jan & John Eklund, New Mexico; Steve Pigott, Georgia; Lisa Johnson, Florida.

In Central and South America: Linda Cox, Costa Rica; Judith Hamje, Costa Rica; Ryan Korniloff, Colombia; Diego Barrera, Ecuador; Rosemary Gordon, Peru; The Cordano family, Peru.

While compiling this page, I realized how much, ‘No man is an island.’ Assistance has arrived from all over the world in numerous ways while completing this book, including mechanical and veterinary advice by e-mail, small loans, gifts and unlimited bones for my dogs. A few of these people include: Steve Slampyak, Switzerland; Ray & Jane Hogger, California; Matthew Kleinosky, Canada; John Leydon, Virginia; Rosemary Tylka, Switzerland; Mary Heys, Italy; Tod Green, California; Janet Bullbox, Kansas; Ray Briggs, California, Therease Humpston, California; Dave Houser and Jan Butchofsky, New Mexico; Stephen Anderson, Virginia; Dave Hess, California; Dr. Yvonne Provci, Florida, Floyd the Dog; Leonard Young, California; Phil Hall, Florida; Doug & Trish Baum, Texas.

Thank you to the editors of Fido Friendly, the first magazine interested in the adventures of Dog, Bruiser and myself. The publishers watched me grow as a writer while publishing excerpts from On a Mission from DOG and our current exploits.

This book is dedicated to Fred Midikila,

Jean Gillchrist MBE, and the many

devoted workers at the Kenya Society for

the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

I don’t pretend this book is a completely

accurate documentation of my five years

living in Kenya. As L.P. Hartley wrote in

his book, The Go-Between,

‘The past is a foreign country;

they do things differently there.’

To my Dad, thank you for all the stories that introduced me to a wilder world beyond my bedroom window.

Introduction ‘You’re going to have to be pretty careful when you move to Kenya,’ I’d been cautioned like a little girl. ’Africa is a dangerous place.’

‘Yes, yes,’ I would reply to men friends who gave the dire warnings, rarely women, who seemed less worried and more elated. ‘Don’t forget, I have been living in Egypt for seven years.’

’Ah yes, but where you’re going is different. Kenya is black Africa. And black Africa is another world… ’

‘I was in Senegal, that’s black Africa.’

‘Yes. But that’s West Africa…‘

‘I’ve been to the Sudan too. And I did spend six weeks traveling by camel across the Libyan Desert.’

‘Maybe so. But where you’re going is like nowhere you’ve ever been. There’s a reason they call the capital of Kenya, Nairobbery…’

After the packers left with our belongings all secured and taped in uniform cardboard cartons, our flat in the Cairo suburb of Maadi was an empty shell. Then John left for England. Spending a blistering August in Egypt waiting for him to return from visiting family seemed intolerable. Cairo, usually teeming with life, was desolate. Locals left the sanctity of the Nile for the cool breezes of the Mediterranean coast. Many of the 40,000 expatriates flew back to their country of origin. In their wake flocked Saudi men, shrouded in white from head to foot like cattle egrets, while their women glided like black kites through the cosmopolitan city of twenty million — winged migrants escaping their desert heat. I longed to begin my new life in Kenya.

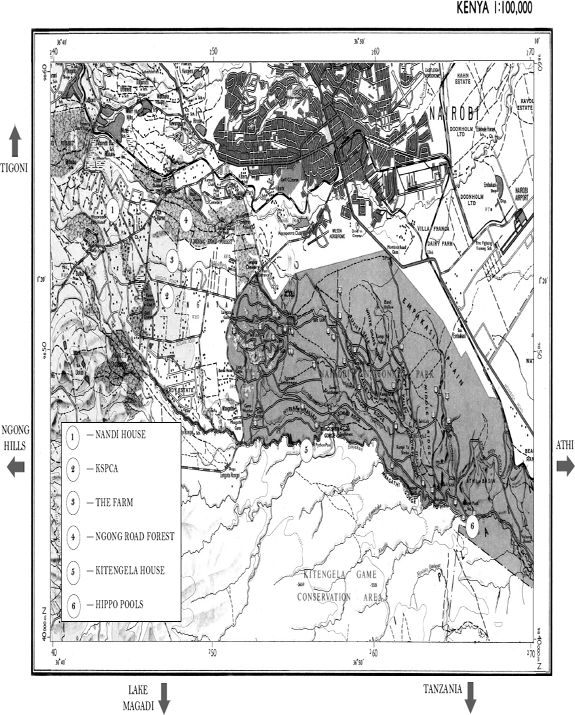

Despite my initial confidence, by the time I landed at Jomo Kenyatta airport the nay-sayers had done their work. I was terrified of the massive onslaught of rapists, murderers and thieves who awaited my arrival. The house chosen by the school for my new husband and myself was in Karen, on the outskirts of Nairobi. Named after Baroness Karen Blixsen who penned Out of Africa, we occupied one of three houses on six rolling, parklike acres, concealed from one another’s view and the sky by tall trees. The area seemed permanently enveloped in a fog which didn’t lift until late afternoon — if at all. It was dark. Giza sena, very dark, were my first Kiswahili words.

During my years in Egypt I longed to be removed from Cairo’s noisy streets and monotonous tan buildings. Once in Karen I sat enveloped in green foliage for as far as the eye could see, only occasionally seeing a car navigating its way from a hidden house down a long driveway. Mentally, I superimposed Cairo’s chaos onto the pristine landscape, hoping to recapture what I’d once loathed. I yearned for life.

Black Africans walked along Nandi Road, a long potholed track, to and from work, employed behind the high hedges as housekeepers, gardeners and cooks for the largely white population. Men who were askari’s or security guards hung out at the nearby kiosks during daylight hours. Then from six at night till six in the morning, they made sure the populace was protected behind their barred windows and doors.

There was a forest nearby where baboons and Sykes monkeys lived. I longed to experience primates outside a television box where they’d been held captive since I was a child. But I was told men, white men, had been mugged while jogging in the forest, wedding bands forced from their fingers. This was my introduction to ’Nairobbery’. Travel and wildlife were two of my passions and I was desperate to stray further afield. I didn’t dare.

Asphyxiated by fear, my adventuresome nature came to a grinding halt. My home became my tomb. I was quickly going berserk (though certainly not quietly according to my husband) inside our white painted house in the white neighborhood, struggling to hold off until noon before drinking my first beer of the day. Then without warning and after six months of self-imposed isolation, I snapped. It was three o’clock in the afternoon when I wrenched myself away from the computer — my source of companionship from the time my husband left for work at seven, until arriving home before dusk. In the kitchen, instead of grabbing a second bottle of beer, I went directly to the black, wrought iron back door and swung it open. The sun had only just emerged from behind the Bombax tree, whose one inch thorns lay half hidden in the grass. Hesitating only momentarily, I pulled the wooden door shut behind me, turned the lock, secured the outer metal portal with two padlocks, stuffed the keys in my shorts pocket and began walking down the dirt driveway. Casually looking to see if anyone was watching, I returned to the poinsettia tree and hid the keys under some dusty, brown leaves at the base of the slender trunk.

I strode quickly along the length of Nandi Road, across Miotoni, and up the other side. Where the road bent to the right to continue to other white occupied homes, I did the unthinkable — I walked straight into the forest where black Africans were heading. Stumbling down a hill lined by eucalyptus and stray bits of garbage, I struggled up an even steeper trail on the other side. People with skins tones greatly darker than my own either ignored the only white person on the commuter path, or greeted me by saying, ‘Jambo.’ My voice replied cheerily — my feet kept their brisk pace.

I began walking a few times a week. Then everyday. With my neighbor’s blessings their two dogs began accompanying me. The mini-adventures became my lifeline. I still hated the house but walking with Rico, the first dog I ever loved, made it bearable. Highly intelligent, he looked at me with calm, captivating intensity. For the first time in far too long my late afternoons became filled with laughter and fun which carried me throughout the day. Then one morning after making my groggy way to the kitchen to prepare tea, I found a note hastily scribbled on the back door: Please do not walk our dogs anymore. From now on, they need to stay at their own home. I’d known the love between us couldn’t last. At my insistence, John and I had already begun the search for new accommodation. Nevertheless, I was devastated.

At eighteen I left home (by which time I realized cats and dogs could be both sexes) and acquired cats. Or they acquired me, as they do. Because of my feline oriented childhood, my knowledge of dogs was not dissimilar to my knowledge and intimacy with babies and children. I knew few who had either and was quite happy for things to remain that way. After all, dogs were silly and not very intelligent. Opinions about babies and children I kept to myself.

Bursting from the wooden barn, a stocky African man runs to a faucet sticking up out of the ground and hastily fills a bucket with water. He hasn’t seen me approach.

‘Excuse me, I’m looking for Mr. Mburu. Is he here?’ The man wears dungarees made of blue jean material cut in the same style you’d expect to see in a documentary about sharecropping in the South. Startled eyes look up from his round face rimmed with curly gray hair and then to the barn. I follow his gaze. Inside the dark interior I detect a man standing at the rear of a cow, his arms buried deep inside the heifer’s birth canal. The whites of her eyes bulge. From the rafters hangs a heavy chain in readiness to wrench the calf from its comfortable haven, and onto the straw covered floor.

Torn between politeness and his task, the man stutters. I’m only able to catch the Kiswahili words ndeo and la’a for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ before the man is gone, water sloping over the sides of the bucket and disappearing into the burnt red soil. I grasp the opportunity to investigate the rental property in private.

At the end of a small private lane, sheets of ugly black metal loom a few meters taller than my petite frame. The seemingly impenetrable obstacles are typical of gates all over Nairobi. Heaving my shoulder against the steel, I squeeze through the narrow opening. My heart sinks. ‘It’s fine, let’s take it,’ John said yesterday afternoon during the glow of magic hour.

A cottage yesterday, today it’s a shack. With no phone. In the eleven months we’ve lived at the Nandi House, the telephone’s been out for four. After endless hours spent at the exchange believing my polite but persistent presence would give me access to the outside world, I’ve learnt it’s chi, a small token of money, not charisma that gets things done in Kenya. Bribes are not in our budget. Cell phones not yet affordable.

Unlike the lush but oppressive Nandi compound, the garden surrounding this house is small, flat and fenced. Though both are within a few kilometers of what were once the coffee plantations of Karen Blixsen, neither abode remotely invokes for me the opening line, I once had a farm in Africa… Morning sun should be streaming through eastern facing windows covered with thin wire mesh. But the openings are small and the black cement living room floor, adjacent to wood wall paneling, sucks up light like a black hole.

All the other houses viewed thus far have been nixed — the result of our often differing, but equally finicky standards: Too far from the school where my husband’s been teaching the past year, gardens too densely forested for me, too open for John, or the rent too expensive for us both. This is our last option. I peer into the living room again. ’Maybe it’s brighter when the front door’s open… ’

As I circle the perimeter of the house, peering in bedroom windows as stingy as their living room counterparts, a dingo-like dog with tall ears and a curled tail runs through the rickety back gate. She whimpers excitedly. I erect my I’m-not-interested-in-another-animal façade. Though still young, shrunken nipples pulled down by nursing pups dangle beneath her gaunt ribcage like two rows of tassels hanging from partially lowered curtains. Cream colored fur offsets stunning kohl-rimmed eyes. I feign indifference.

Sensing this first audition to be crucial for her survival, the dog rolls on her back in the ultimate display of appeasement — a consummate actress. On cue I bend down. Partially bloated ticks hang desperately to her emaciated belly, extracting blood unlikely to contain many nutrients. Patches of fur devoid of ticks are inhabited by colonies of fleas. I cringe and turn away. Spellbinding deep brown eyes draw me back. Fighting repulsion, my fingertips graze over her dull, dusty fur. She lowers her head, ears drawn back in submission. From the other side of the white picket fence comes the cry of seven malnourished puppies. Falling clumsily over each other and into the garden, the mother snarls as they near. Though our reasons differ, her opinion of infants are similar to mine. We bond.

While maintenance men paint the bedroom walls of our shack white and smear another coat of black across the cement living room floor, the furniture sits temporarily in the garden — the dog nestled on the maroon striped settee. When my husband returned home, she slunk over to low-lying border plants to curl up unobtrusively like a cat. John and I sit on opposite sides of a round wooden table with peeling blue paint. Both of us drink Tusker beer from bottles with crudely drawn elephants on the labels. From a clear, crinkly plastic bag, we pick out the sturdiest pieces of vinegar flavored chips. They collapse from the weight of my salsa — homemade, as the imported variety is exorbitantly expensive.

We exchange banter before John asks, ‘Does that dog have to be in our garden?’

‘She’s sweet.’

‘She’s manipulative. She’s trying to work her way into our lives.’

‘That’s silly. Anyway, I thought you loved animals.’

‘I love wild animals. And that’s why I love them, because they’re out there in the wild.’

‘You didn’t mind when the neighbor’s dogs came around when we lived on the Nandi compound.’

‘That’s because they were the neighbor’s dogs. They already had a home.’

The dog’s ears lie flat as she warily watches our discussion, her body curling into a tighter ball and sinking deeper into the ground. When the conversation goes in circles, as is the case with most of our disagreements, John creases the latest edition of The Sunday Times of London in half before folding his reading glasses and tucking them into his vest pocket. Carefully, he transfers Littles’ frail body from his lap to mine, goes into his office and closes the door. My last remaining cat barely acknowledges the shift in vantage points.

When John and I’d met in Egypt five years before, my three cats were our first point of contention. I’d once seen a refrigerator magnet imprinted with the words, Sleep with me, sleep with my cat. I wanted to own the philosophy, if not the magnet. John had spent neither his childhood nor his adult life around animals. When my cats insisted on their usual routine of climbing on my bed at night, John couldn’t sleep. After a few tense exchanges, the last while one of my cats clawed relentlessly at the bedroom door to be let back in, we agreed nights together would be spent more peacefully at John’s flat.

As the love between the two of us grew, so did John’s affection for my cats. Only Littles remains. She’s nearly nineteen. The familiar motion of stroking her still silky fur calms rage which has taken me by surprise. I don’t want another animal. For years I’ve longed for a time when I don’t need to search for pet sitters and worry while away. With guilt, I yearn to travel guilt-free.

New house, new beginnings, I think, reminding myself how John and I have worked as a team on the Farm in a way we never did at Nandi House. I lift Littles in my arms and walk over to the settee before depositing her onto a cushion. The dog tilts her muzzle down and her gaze up — the angle making them appear even larger when new moon white discs beneath her brown eyes are revealed. ’Don’t forget about me,’ her look conveys. John joins me in the kitchen, and while making dinner together, he and I hold each other tight and make amends. I agree to stop feeding the dog.

The next morning, I start John’s coffee before opening both the wooden and metal front doors. Sunlight streams into the front room. The dog, already at the doorstep, greets me eagerly. I don’t respond. Her wagging tail slows, then droops. Her brown eyes look quizzically into mine. I waver. No. I can’t. Resolutely I walk straight past her to the bird coop where the two ducklings we brought with us from Nandi have spent the night. I pour the usual amount of poultry mash into the bowl. Then add more. Quite a bit more. I place the gruel mixed with water in front of the ducks and return to the kitchen as the last drops of coffee fall into John’s cup. After delivering the brew I peer out the window — just in time to see two gorged ducks waddling slowly away from their bowl and the dog consuming the excess meal.

Thirty minutes later I kiss John goodbye and watch as he walks through the back gate, then down the Mburu’s narrow tarmac drive — all part of the daily ritual which takes him to Hillcrest Secondary School. By the time he reaches the second gate and pauses to observe egrets nesting at the pond, I’ve returned to the kitchen.

Grabbing a plastic container, I wipe up John’s breakfast spillage along with leftovers from the night before and scatter the spoils of my pillaging onto the compost pile. Slices of bread best left on the ends of loaves to keep the inner core fresh, find an early but brief home on the heap, as do scraps of onion peel, papaya and avocado skins. The dog devours a diet meant for herbivores, birds and insects.

For the sake of domestic tranquility, by the time John arrives home from work I’ve re-erected my she’s-not-so-important-to-me façade. It’s just a façade. While John continues his crusade to keep the enemy out, like a traitorous wife, I conspire to keep my new friend in.

2 The administration at John’s new post considered it unusual for the wife of a teacher to arrive in Kenya before the husband. When I met with our new landlady, the colonial matron refused to discuss anything of substance without John being present. I was obviously an insignificant female twit and couldn’t possibly know anything about money, plumbing or electrical issues. However, she did permit me to oversee workers who roller and painted the walls inside the house standard, flat, bright-white.

After John arrived we accepted endless invites for sun downers, the expatriate term for cocktails at sunset. Hostesses wearing cotton dresses with tiny floral patterns persisted in introducing me as Mrs. Dawson. I persisted in correcting them. I displayed my first book prominently on our coffee-table, and told anyone who’d listen about my publishing background and adventures throughout the Middle East. I’d assumed my creative work would be my calling card. But few seemed able to conceptualize I might actually have a life outside my husband’s teaching career.

I recollected and reenacted my mother’s ire, who after winning a bread baking contest in the early 1970’s, was irate when the newspaper wanted to print her name as Mrs. Chris Chittock. In Cairo, amongst a population of 40,000 expatriates I had my own name and life. In Kenya I was assigned someone else’s.

Shortly after moving into our shack I wander over to the landlord’s house. The dog follows. A one-hundred gallon aquarium — empty, with dry peeling algae lining the glass walls, is the first thing I see when a housekeeper opens the heavy wooden door. Next to the aquarium, sprawled on a long narrow table is the body of a dead lioness. Stuffing comes from the anus.

I step into the two-story foyer. The dog stays on the outside step. Tall cabinets filled with trophies commemorate a time when Mrs. Mburu was one of Kenya’s top golfing stars. From the tomblike interior comes the drawl of a Southern woman. The American accent is distinctly out of place. I’m ushered through the darkened abode to where Mrs. Mburu sits on a settee upholstered with drab fox-hunting scenes. Drawn curtains keep the heat from the raging fire inside and the sunny day out.

A television mounted near the ceiling is filled with big blond hair. Huge black eyelashes flutter while a heavily lipsticked mouth extolls the virtues of Christianity. On the wall opposite hangs a zebra skin. Depiction’s of horses and Tudor homes are molded onto brass discs and attached to lengths of dark leather. Often seen in rural English pubs, they’re identical to those my transplanted parents hung on our American mantelpiece to remind them of the country they’d left.

Mrs. Mburu’s brown wigged head nods regally towards me in greeting while the blonde on the screen encourages viewers to pledge their dollars.

‘How is your health?’ I ask, taking a seat opposite. A stroke suffered the year before left one side of her body partially paralyzed. A housekeeper sets a lace doily on a tiny circular table, and then a cup of tea.

‘I am getting better every day, thank you.’

‘I am really enjoying living on your Farm,’ I say, speaking too carefully and using simple words, though Mrs. Mburu’s English is perfect. ‘Just after sunrise, I walked down the lane to where that old blue gate opens onto the banana plantation. Some Ibis were flying to the pond. It was very beautiful.’

‘Umm, yes,’ Mrs. Mburu says, leaning back in her seat, her outstretched hands grasping the top of her walking cane like royalty holding a scepter. The hierarchy is clear. This is her Farm and her country. I am her tenant.

’And how is your dog?’ she asks.

Nothing John nor I do goes unnoticed amongst the Mburu’s many workers. Someone must’ve seen me feeding the dog scraps.

’You mean the one who stays with our askari at night… She’s fine, ’ I reply vaguely, refusing to be responsible for one of the many mongrels who roam the Mburu Farm. I just hope the dog isn’t waiting for me on their front steps.

And half hope she is.

‘She is a good guard dog,’ Mrs. Mburu asserts.

‘Yes… ’

‘She originally came to the Farm with an askari. We let him go but kept the dog because she is so good.’

‘I’m sure she’s a wonderful dog, for you,’ I assert, refusing to be coerced into adopting another animal. Especially one with seven puppies, each of them causing stress in my marriage.

‘Mr. Mburu mentioned the Farm used to be much larger, two hundred acres. You must’ve been sad to sell this land.’

Mrs. Mburu peers over the top of her cup of tea, chuckling from the side of her mouth still supple. ‘Sad? You have seen all these big expensive homes being built? Selling this land has been like money in the bank.’

‘Yes. Money in the bank,’ Mr. Mburu echoes from the kitchen, milling amicably amongst the staff. Most work six and sometimes seven days a week, almost twelve hours a day for the barest of wages. One of the women approached me surreptitiously, hoping for more lucrative, if less stable employment in our expatriate household.

Retired from Kenya’s largest brewery, Mr. Mburu now assumes the role of gentleman farmer, making sure the help properly tend the cattle, goats, chickens, geese and other money producing animals. There are also six dogs who’ve struggled to gain my affection by shoving their snouts against my various body parts. When not accompanying Mr. Mburu on his rounds they prowl lean and hungry-eyed around the perimeter of the estate, looking for scraps to supplement their meager rations.

‘You know, Mr. Mburu, there’s an animal organization just up the road. They can fix all your dogs for very little money. It must get expensive feeding so many litters… ’ I suggest, having noted one of the two bitches is pregnant — their drooping teats testament to numerous litters.

‘Yes, yes,’ he agrees jovially. ‘I must look into that… ’

‘What will you do with the puppies?’

‘Would you like one?’

‘No… ’

‘You should have one, they make good guard dogs. Let me know if you change your mind. My friends love it when I give them puppies.’

I wonder if Mr. Mburu’s friend’s view his gifts so magnanimously.

‘Bloody rich git Africans,’ says Theo, who works at the Kenyan SPCA. ‘They’re always the ones least interested in taking care of their dogs. Bloody awful.’

Kenyan Cowboys or KCs, is the term coined for whites born into old colonial families. Elite bums is how Theo describes herself and her friends. Educated in the finest British institutions, many struggle in entrepreneurial fields after returning from boarding school. Safari companies and businesses catering to tourists are favored occupations, the influx of Western funds allowing the KCs to revel in a lifestyle of excess and heavy drinking for which cowboys and cowgirls are renowned.

‘Tell you what we can do,’ Theo says, leaning back against the donkey paddock. ‘I’ll send a couple of our boys over to the Mburu Farm. They’ll talk to him about all the unwanted dogs on the streets — then tell him he’s got to spay his animals.’ As she wags her finger fiercely to an invisible Mr. Mburu, two rabbit-size mammals appear to cavort and jostle for space underneath a plain dark shirt struggling to conceal her voluptuous frame.

‘Don’t let Mr. Mburu know I’m involved though, ok? We’ve only just moved in… ’

‘Oh God no. And we won’t charge him, just ask for a donation.’

‘I wouldn’t worry. He’s loaded.’

‘No doubt. But if we charge, he won’t go for the idea at all. What do you want to bet the rich git just gives us bloody cabbages from his Farm in lieu of dosh? Bloody Africans, all bloody the same… How many females are there?’

‘Two. And four males.’

‘All shenzis?’

‘Shenzis?’

‘Mixed breed, mutt. What they’re called here.’

‘Shenzi… what a great name.’

‘Yeah, but not something you want to call someone at night in a dark alley. Anyway, we’ll do the females. As usual we’re having a hard time making ends meet. Always got over a hundred dogs. Got to keep doing these bloody fundraisers until the government decides to help. That’s bloody unlikely… ’

‘You can’t fix the males?’

‘Can’t afford it. We just do the females. They’re the ones giving birth. Bloody unfair, especially as the operation is trickier. And more expensive.’

‘Well, the two females are at the main house. And there’s another hanging out at our place. I guess she’s a shenzi too. Really sweet. She’s already had puppies. A few died. I’m not sure how many are left… ’

‘Why don’t you keep her?’

‘A dog? With puppies? That’s the last thing I need.’

‘We can find homes for the pups, no worries. Take the dog. Ah, come on Lorraine!’

‘Absolutely no. I’ve got a nineteen year old cat on her last legs. After she’s gone, no more pets. Just once I’d like to travel guilt free.’

A few days later, a white truck with Kenya Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals stenciled on its side pulls up outside the main gate of the Farm. I hide. The next morning the truck returns. I watch as men put the two pregnant bitches in the enclosed pickup and close the door.

‘Excuse me, there’s this one too,’ I say pointing to the small tan dog. The dog looks at me adoringly. When the men pick her up I turn away, but not fast enough to avoid her look of alarm. I feel like Judas.

I resume writing. The hours on my computer screen change slowly. I wonder how the dog is doing. I focus on a new chapter. My mind wanders. The surgery should be finished. My stomach is tight. When the numbers on the screen eventually turns to three, I decide to make a quick trip to the duka’s. We need more meat for tonight’s stir-fry. Then I’ll drop by the vets… just to make sure the dog is ok. I start up the Land Rover and head straight for the vets. I forget my purse.

Across from the vet’s office are two cold, concrete buildings divided into kennels. When the dog sees it’s me getting out of the Land Rover, she squeals and whimpers in delight, reaching her paws up against the wire.

‘Oh no,’ I say, noticing her belly looks no different than when I last saw her. Guilt returns. ‘You’ve been stuck in here all day, and nothing’s happened?’ I talk soothingly, but avoid appearing too interested. She’s not my dog.

Twice a week, John and I take turns driving Littles to the vet. The treatment staves off the inevitable for only a month. It’s a few days before Christmas when Patsy steps through the black gates which are partly ajar. The dog barks, the sharp sound piercing the soft morning air. When Patsy and her assistant enter the bedroom the dog offers frantic warnings.

‘Shush,’ John insists. The dog yelps even more. Sitting cross-legged on the bed, my fingers stroke silky fur wet with tears. Patsy enters the room and kneels next to me, nodding her head in brief acknowledgment, before murmuring soothingly to Littles. Patsy’s brusque nature when dealing with people is renowned — in the realm of animal doctoring her word is sacrosanct.

In moments I’ll be released from my last cat’s furry and friendly shackles. Not until now do I recall empty hotel rooms, photos of my animals propped upright on night stands, and the hollow feeling when my body, in-between the crisp sheets of a strange bed, has no warm animal to curl around — as familiar a sensation as if their bodies were an extension of my own.

Littles’ body lies limp. Instead of feeling weightless and free as the wanderlust side of my personality had beguiled me into believing, I feel anchor less and heavy.

‘It’s no good, Lorraine,’ John says, returning to our bedroom. ‘The dog won’t stop barking. She knows something’s wrong. She’s probably worried about you.’

‘You’re lucky to have such a perceptive animal,’ Patsy remarks, while putting medical instruments back in her bag. ‘That one will always take good care of you.’

I daren’t mention she’s not our dog.

After Patsy leaves, I carry Littles’ body to the front door. The dog whimpers upon seeing me. In a rural landscape dominated by canines, the dog had never encountered a cat prior to Littles. Instead of taking the opportunity to investigate a creature she’s deemed fascinating but regarded warily, she reacts as though what I’m carrying is not Littles, but merely the towel I’ve wrapped around her body. The dog walks away disinterested. My hands feel empty. I am finally free.

3 When the Gods created sex, the main function was procreation. Our Creators must’ve looked to the future and foreseen that during times of overpopulation sex could be scaled down to simply providing pleasure — a fun activity and the supreme game. And like the best of games participants could play for free. Not only would the amusement include variety, the diversion would be inherently simple with little training necessary. One of the greatest gifts to mankind, the game could be played day or night, in all kinds of weather, without regard to racial, cultural and religious boundaries.

In our society sex is serious play. We call it‘the sex act’. Do we use the term ‘act’ for other bodily functions? The food act? The bowel act? The act of urination? For how many is sex an act? When working as a bartender I knew a cocktail waitress who said, ‘I hate having sex first thing in the morning. I like having my make-up on.’

Movies show us how to look while we kiss, heave and thrust. Only during our most passionate moments do we completely forget how our breasts look from a certain angle and if various appendages flop — or not. We want to look gorgeous while we moan and groan in abandon. But how can you abandon yourself if you must look gorgeous?

At some point the game became flawed. Perhaps in the process of creating Adam and Eve, refining the nuances of sexual interaction became tedious for the Gods. Or maybe they decided to reinvest their time inventing more appreciative species. Like the dog.

The dog accompanies me to pastures belonging to a white Kenyan family whose horses were ridden in Out of Africa. We’re greeted by a Labrador and a lean whippet-like creature. Within minutes the three are biting and bumping forcefully into each other, reveling like children whose parents aren’t around. When the canines begin chasing each other, I yell to the dog, ‘Go, go!’ as if I’ve bet money on her at the track. Instead, I’m the only person in a large, empty field. Excited by my enthusiasm the dog bounds towards me, her body twisting in mid-leap, her mouth wide open in a grin. Waving my arms, I leap back and forth, then jump up and down while making goofy noises, quickly out of breath. She charges at me, throwing her body against mine. I continue turning awkwardly in circles, the dog responding with less and less enthusiasm, and eventually returning to her friends. The dog plays with abandon. I need more practice.

Showering off stray bits of mud and dirt back home, I reluctantly put on fresh clothes. Today is Friday — Fish and Chips night at the Karen Country Club. A few of John’s higher earning colleagues recently splurged on membership. Seven poorer teachers and myself are their guests. I dread the prospect of an entire evening devoted to talk, talk and more talk.

‘How are you settling into the new place, Lorraine?’ Cathy asks as I sink into one of the settees. Two plump women sit on either side, cushioning my narrow frame like filling in-between puffs of pastry.

‘Fine, thanks. The house was actually… ’

‘Oh, just a sec…, ’ Cathy interrupts, before turning away to pick up a conversation with another teacher.

‘I know! Out of all the times that fellow’s been in detention, you’d think by now… ’

‘Does he really think it’s attractive?’

‘I can’t imagine!’

Teacher get-togethers dissolve tensions after an intensive week surrounded by Asian, African, colonial and expatriate students, all desperate to disobey the school’s strict dress code. John spends untold energy telling boys to keep their white shirts tucked into their navy blue trousers. I spend untold energy trying to convince John his teenage students need to express themselves.

‘And dyed purple?!’

‘I know… Can you believe what she wore underneath?’

‘Does she really think anyone will see it?’

‘Knowing her, someone will… ’

‘At her age I’d never have…’

‘ I would’ve… and did.

‘I hear you’ve moved into a new house,’ says Tabatha, after I’ve extricated myself from the suffocating sofa and moved to an empty chair.’ Do you know when they had the last break-in?’

John had asked this same question before we moved to both Nandi House, and the Farm. Metal bars covering the windows and doors, guard dogs and security guards are prevalent throughout Nairobi because of ineffective emergency services. Dialing 999 links to a police force unlikely to respond promptly, if at all. To compensate, everyone provides for their own protection. Cynics say a corrupt police force combined with a hyped security situation is a way of getting stray dogs off the street and into gardens to guard, and African men gainfully employed as askaris.

‘Well, the security is actually quite laughable,’ I reply. ’We’ve got these huge massive gates an army tank couldn’t budge. But the other day I realized I’d forgotten the key. Shimmying over the top couldn’t have been easier. And even though the front door is made of heavy wrought iron, the windows are covered with metal barely thicker than chicken wire. My Nan could cut through them with her sewing scissors,’ I say laughing while rolling my eyes.

‘I’d be terrified!’ Tabatha says, lightly penciled eyebrows joining forces above a delicate nose. ‘Maybe you should get a dog. I’ve heard a smart dog is the very first layer of defense, what with their sense of smell and suchlike.’

After frightening myself into seclusion during the first six months living at the Nandi House, I’ve decided Nairobbery is no more dangerous than most American cities though admittedly, exaggerated rumors do make for entertaining dinner party material.

‘Yeah, I’ve heard it’s better when dogs work with a security guard,’ I reply. ‘Though I can’t imagine our new askari coming to anyone’s rescue, dog or no dog.’

‘Oh dear,’ sympathizes Tabatha, ‘it sounds like you have a version of my last askari. Old Maasai fellow. Always drank cups of tea and who knows what else with his friends, jabbered all night long. Woke me up at all hours! Carried a spear. Very impressive looking, but he had a wonky eye. Must’ve been half blind. Can’t you get another?’

‘I think he comes with the house. He lives in a little wood shack just behind us with his wife and kids. Anyway, I’d trust the dog far more than any askari.’

‘Oh, so you do have a dog.’

‘It’s not our dog. And not really the askari’s dog either. It was there when we moved in. But we’re not interested in having another animal… ’

‘Really? I thought you were a huge animal lover.’

‘I am… ’

I look to John, hoping he can provide some distraction. He’s sitting with a group of male teachers, all Everton fans who are morose whenever they lose to Liverpool or any other soccer team — which is often. Predictably, Everton have lost again. John is thoroughly enjoying himself despite this let down.

‘Bloody goalie,’ the banter drifts from across the room. ‘If only he’d just keep his eyes on the bloody ball and stay out of the bloody field… ’

John has on his favorite head covering, a well-worn, Irish flat-cap his Mum has repeatedly tried dissuading him from wearing by buying him a newer one every Christmas. Her ploy never works. From one ear dangles his favorite earring — silver, inlaid with mother of pearl. The piece of jewelry, in marked contrast to his usual schoolteacher attire, shows visibly on his bare neck. While in England he received his annual haircut — short-back-and-sides. By the end of the school term and with longer hair, teachers will compare him to Keith Richards. Always my secret ambition to be a rock and roll star, being married to a look-a-like is as close to that dream as I’ll ever get. Neither of us naturally gregarious, we’re often ready to leave social events early. Tonight John is on a roll. I know he’ll readily offer to ride home later with another teacher so I can take the Land Rover. I should want him to continue enjoying himself without me. Tonight, I can’t bear the thought. I glimpse again in his direction. He definitely won’t be rescuing me. After a few more exchanges with Tabatha I excuse myself and say goodnight to John.

On the way to the parking lot I dip into the women’s bathroom. Rows of cubicles, some for changing, some for taking showers after tennis or golf, line the brightly lit room. Tall mirrors behind the row of sinks reflect even more light. I stand in front of one. My eyes have a deer-in-the-headlights look and the circles beneath them are heavy. The bright orange silk top I put on at home while feeling rebellious overpowers my face and mood. I slap on another coat of lipstick which makes me look gaunt as opposed to slim, pull my hair back and return to the pub, sidestepping offers to join the women on the settee who now resemble melting marshmallows, and making a beeline for a tiny table occupied by one of the few African teachers, John Sibi-Okumu. Educated in England, France and Kenya, the impeccibly dressed man has appeared in a multitude of plays and a few films including the Oscar-winning, The Constant Gardener. After regaling me with details about his latest radio and television projects, I recall his appreciation of nature and ask, ‘I’m wanting to explore the Ngong Road Forest.’