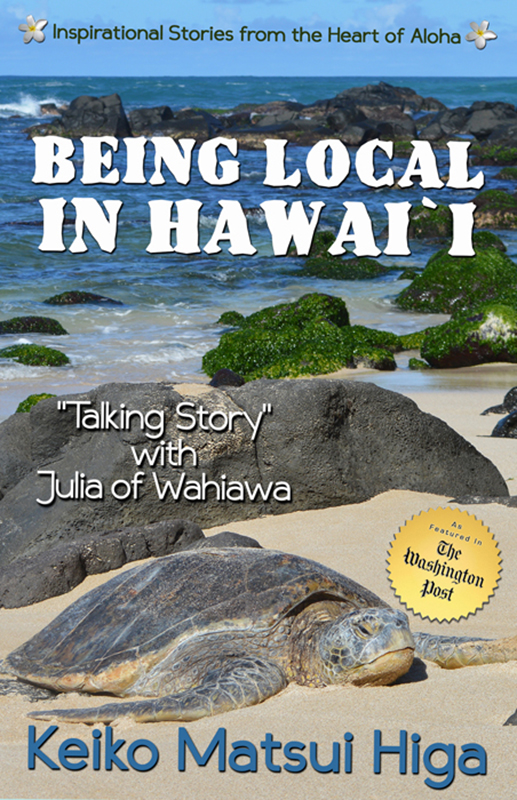

Inspirational Stories from the Heart of Aloha: Being Local in Hawai’i

Talking “Story” with Keiko Matsui Higa

© 2014

Disclaimer: All websites referenced in this book are not maintained or owned by the author and may have changed since the publication of this book.

Cover Layout & Interior Design: Fusion Creative Works, fusioncw.com

Cover Design: Nicole Gabriel

Photographer: Robert Matsui Estrella (Baha’i gardens and shrines and recent family photos)

ISBN: 978-1-940984-15-5

ISBN: 9781940984339

Published by

AVIVA Publishing

Lake Placid, New York.

www.avivapubs.com

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to:

Palikapu Dedman, Oscar López Rivera,

Yuri Kochiyama, and Kekuni Blaisdell

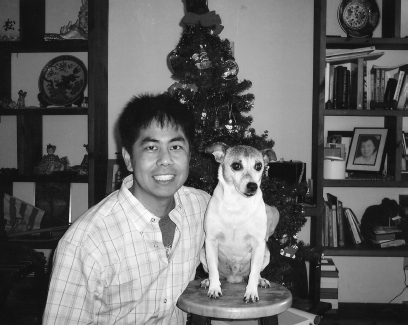

A big “mahalo” to my son, Robert, who has been my biggest supporter for the last forty-five years. Words cannot express the gratitude I have for his never failing assistance in whatever project I undertook and continue to undertake.

Thank you to my husband, Roger, who unfortunately died of a stroke in the year 2002. Roger and Robert were inseparable and they kept our family in balance and harmony. The word “interdependence” has been my mantra all these years because of these two wonderful souls in my life.

This book would not have been published in a timely manner had I not attended the Baha’i School this past summer in Eliot, Maine. For all the support and ideas I received from the participants in the “Spirit of Children” class, I am most grateful, especially for Phyllis Ring, who emerged as one of my editors.

I thank Nia Aitaoto for her networking skills in setting up speaking engagements for me and in her overall support in writing this book.

Thanks also to Patrick Snow and his organization for guiding me to finish this book in five months, an incredible feat. Mahalo to Patrick and the rest of the Snow team: Tyler Tichelaar, who did the final edit; Nicole Gabriel for her front cover design that truly captured the book’s essence; Shiloh Schroeder, who created the beautiful interior layout; and Susan Friedmann of Aviva Publishing for being my publisher.

And finally, “Thank you” to all our family’s friends and relatives—our extended ‘ohana—who made our life experiences so meaningful and rich.

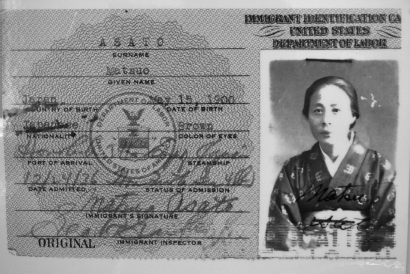

Robert “Bob” Estrella and Mochi—Our favorite dog.

Prologue: K kaniloko by Jo-Lin Lenchanko Kalimapau

kaniloko by Jo-Lin Lenchanko Kalimapau

Introduction

PART ONE: DEEP ROOTS

My Mother: Matsuo Higa Matsui

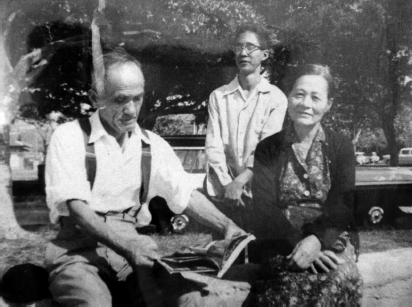

My Father: Kyozo Matsui

Sisters: Peas in a Pod

World War II Hits Home

The English Standard Test

Disaster Strikes

Tanaka Sensei—A Renaissance Issei Woman

An Eye-Opening Mentor

Jumping Jacks and Public Education

PART TWO: GROWING BRANCHES AND BUDS

Being Okinawan

A Love Story

The Philippine Connection

The Best Birthday Gift

Mary and Miya: A Poetic Tribute

Invisible Institutional Racism

Healing Racism

Nine to Five

Robert Estrella in Samoa

PART THREE: THE FLOWERING TREE: SERVICE

Signs of Hope: ‘Ohana Ho‘opakele

Oscar López Rivera

Letter from Nozomi Ikuta

Lead On, O Cloud of Yahweh

Yuri Kochiyama

Peace for Life

Lessons from Civil Disobedience Actions

People of Okinawa and U.S. Bases

Micronesia and the Solomon Report

The Scariest Story

PART FOUR: HEALTH IS EVERYTHING

Living to Be 128 Years Old!

Ola

Health and Solidarity

Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell

Body Wisdom

Mokichi Okada Association (MOA)

Iatrogenesis

Christmas Letter to Jeanine McCullagh

Reinventing Health Care

Comfort Food

Epilogue: Awareness and Action

A Final Note

APPENDICES

Rearview Mirror by Bob Sigall

Pidgin Test

About the Author

K KANILOKO… “TO ANCHOR THE CRY FROM WITHIN”

KANILOKO… “TO ANCHOR THE CRY FROM WITHIN”

by

Jo-Lin Lenchanko Kalimapau

Historian, Hawaiian Civic Club of Wahiawa

L hu‘e, Wahiaw

hu‘e, Wahiaw , Halemano—sacred uplands—the birthplace of the highest ruling chiefs distinguished by the ka`ananiau: a beautiful place in time. K

, Halemano—sacred uplands—the birthplace of the highest ruling chiefs distinguished by the ka`ananiau: a beautiful place in time. K kaniloko is one of the most sacred sites in all of the Hawai’i Islands. This site, kapaahuawa, was first associated with the birth of Kapawa to Ali`i Nanakaoko and his wife, Ali`i Kahikiokalani in A.D.1060. For more than 500 years, here in these sacred uplands, the purity of royal lineages was maintained, giving chiefs their godly status and the right to be leaders. The child born in the presence of these chiefs was called an ali`i, an akua, a wela—a chief, a god, a blaze of heat (Kamakau 1991:38). Cultivation of pineapple in the mid-1900s resulted in the destruction of the temple, waihau heiau Ho`olonopahu. Here at this temple, the recitation of genealogies since time immemorial, time eternal took place; here the piko, umbilical cord, was ceremonially cut; and here the sacred temple drums of H

kaniloko is one of the most sacred sites in all of the Hawai’i Islands. This site, kapaahuawa, was first associated with the birth of Kapawa to Ali`i Nanakaoko and his wife, Ali`i Kahikiokalani in A.D.1060. For more than 500 years, here in these sacred uplands, the purity of royal lineages was maintained, giving chiefs their godly status and the right to be leaders. The child born in the presence of these chiefs was called an ali`i, an akua, a wela—a chief, a god, a blaze of heat (Kamakau 1991:38). Cultivation of pineapple in the mid-1900s resulted in the destruction of the temple, waihau heiau Ho`olonopahu. Here at this temple, the recitation of genealogies since time immemorial, time eternal took place; here the piko, umbilical cord, was ceremonially cut; and here the sacred temple drums of H wea and ‘

wea and ‘ puku announced the birth of the royal child.

puku announced the birth of the royal child.

K kaniloko encompasses 36,000 acres. Boundaries are defined in our chants and mo`olelo—traditional comprehension. The five acre parcel now known as K

kaniloko encompasses 36,000 acres. Boundaries are defined in our chants and mo`olelo—traditional comprehension. The five acre parcel now known as K kaniloko Birthstones State Monument is located to the North of Wahiaw

kaniloko Birthstones State Monument is located to the North of Wahiaw Town. Preservation and enhancement measures, implemented by the Hawaiian Civic Club of Wahiaw

Town. Preservation and enhancement measures, implemented by the Hawaiian Civic Club of Wahiaw for more than four generations, protect and preserve this sacred site in perpetuity. As knowledgeable representatives sensitive to traditional site and land management, we choose to act responsibly without compromising the respect and sensitivity of our Nation, ko Hawai`i paeaina. We look to the voice of our kupuna ma—those whom we choose to follow—who left us with this reflection:

for more than four generations, protect and preserve this sacred site in perpetuity. As knowledgeable representatives sensitive to traditional site and land management, we choose to act responsibly without compromising the respect and sensitivity of our Nation, ko Hawai`i paeaina. We look to the voice of our kupuna ma—those whom we choose to follow—who left us with this reflection:

Respect is unconditional love handed down from generation to generation…

K kaniloko, the piko, metaphysically centered and connected since time immemorial, time eternal, emanates Aloha, the greatest truth of all…e

kaniloko, the piko, metaphysically centered and connected since time immemorial, time eternal, emanates Aloha, the greatest truth of all…e it only begins…

it only begins…

“e kuka‘awe i n kapu o K

kapu o K kaniloko no ka mea aloha no ho‘i k

kaniloko no ka mea aloha no ho‘i k kou ia l

kou ia l kou i n

kou i n kau a kau…” “to guard the kapu of K

kau a kau…” “to guard the kapu of K kaniloko because we love them for all time….”

kaniloko because we love them for all time….”

Growing up in Wahiawa, my favorite spot was the Wahiawa Library and the gulch behind it. I am amazed that my sister and I were able to run down the gulch to the other side barefoot, especially with thick tree trunks protruding all over the place.

During the summer months, I was checking out books on an almost daily basis (except for Sundays). At one point, I felt I had read almost every book in the children’s section.

My uniqueness in enjoying books lay in the fact that I was a “smeller” of books. I loved the smell of books, especially the ones hot off the press. Thus, my addiction early on was the smell of The Jennifer Wish. For over fifty years, I would search for this title in every library I visited. I finally found it listed at the Library of Congress, but unfortunately, I could not purchase the book or borrow it. More recently, I was able to go online and actually purchase a copy at a very high price. I eagerly turned to open the book upon arrival—the smell was not there! Nevertheless, the wonderful illustrations and stories were there and the wonderful memory of childhood flooded back. It was worth the high price.

If only all of childhood could be as wonderful as the smell of that book! But I had some unpleasant experiences as well. Hawai’i has always been a diverse and multicultural environment, and I have lived my life in the midst of cultural diversity…and sadly, some cultural conflicts. The photo of the sea turtle on this book’s cover, taken by my son Bob, is very special to me because it represents the bi-cultural nature of my life. Just as the sea turtle can navigate the ocean and enjoy being on land as well as the ocean, I have learned how to navigate Asian and Western culture. It has been an amazing learning experience and one I hope you will agree is well worth sharing.

This book is the result of my desire to share how I have navigated these two cultures, learning from both and understanding what it is to belong to each one. In these pages, I will share with my readers my experience growing up as a Japanese-American in Hawai’i with an Okinawan mother and later a Filipino husband. I have known what it is to experience racism, and I have known what it is to experience the many joys of life. Most importantly, I believe that our lives have a purpose and any adversities we face will only make us stronger. The wisdom gathered from those adversities needs to be passed on to help others learn and heal their lives. That important need to tell our stories is why I refer to “talking story” in my subtitle.

They say that everyone wants to write a book, but few people do. For many years, I thought it would be too daunting a task to write a professional-looking book and find a publisher. You might feel the same way. So I gave up on the idea until I attended the Spirit of Children retreat and met so many creative people, many of whom were published authors and artists. Then I met Patrick Snow at Manoa Library in Honolulu, where he presented twenty-one mistakes that most of us make in writing and publishing a book. Then he presented solutions to each of those mistakes, and I had a “Yes” moment. I said, “Yes” to all my dreams of wanting to be a writer, knowing that it was not as impossible as my mind had made me believe.

I was also inspired by the Bamboo Ridge collective and press, based in Hawai’i, which publishes journals twice a year with contributions from many local artists and writers. Bamboo Ridge is a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation formed in 1978 to foster the appreciation, understanding, and creation of literary, visual, or performing arts by, for, or about Hawai’i’s people. One can subscribe to the journal by writing to: brinfo@bambooridge.com or www.bambooridge.com.

Also, in keeping with my obsession over the smell of books, I have decided to bless each of my books “hot off the press” with several drops of Wild Orange or Peppermint essential oils. (I’ll share more about my love for essential oils in this book.) There are 250 drops in each doTerra bottle so it will only cost around ten cents for each blessing. And since these are Certified Therapeutic Pure Grade (CTPG) drops, there will be no problems with drug-sniffing dogs at the airport. I hope I am starting a “movement” of sorts in appreciating the power of the smell of “pure” nature (no perfumes, please).

Most importantly, I hope that my writing this book will encourage readers to tell their own stories. I believe it’s true that everyone has a book inside him or her. But even if you don’t publish a book yourself, it is important that you write down your story to pass on to others and so future generations can learn from it. That’s what “talking story” is all about—telling our stories so we can share our wisdom and make the world a better place. The world will be richer when common ordinary people like you and me can share our life experiences and then learn from and build on them.

In this day of Facebook, Twitter, and blogs, I am hoping that some of my readers will want to interact with me by sending me questions, comments, recommendations for the next edition, and sharing snippets of their stories as well.

I look forward to the interaction with my readers and hope to learn a lot from such sharing. Come “talk story” with me by visiting and commenting at: www.keikomatsuihiga.com and www.thatdoterragal.com

Mahalo to all my relatives….for when you participate in reading this book, you join ‘ohana (extended family) circle.

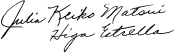

Julia Keiko Matsui Higa Estrella

March 3, 2014

Part One

DEEP ROOTS

“As long as we have life,

We must do our utmost

To combat the schemes

Of the dark forces

Which are trying

To destroy the world.”

— Mokichi Okada

Wedding Photo: Kyozo and Matsuo Matsui

Growing up in Okinawa, my mother had some exciting stories to tell. She was born in 1900 in Kita-Nakagusuku, in the center of the main island of Okinawa, ruled by Japan. She left Okinawa around 1917 to marry an Okinawan man from the same village who was working as an early immigrant in the sugar plantation of Waipahu, Hawai’i. “Picture Bride” was a title given to many of the women who arrived, like my mother, as the result of an exchange of photos between a prospective bride and groom.

Matsuo is a name given only to men, so I asked my mother how she ended up with “Matsuo” on her green card. She explained that there were two girls at the elementary school with the name Matsu and the teacher just decided to call one of them Matsu and my mother became Matsuo. Her elementary school was located on the grounds of the famous Nakagusuku Castle, a place tourists now visit to experience some of the early history of Okinawa.

Her family name was “Higa,” but the indigenous pronunciation is “Fija,” and it means “laughter and happiness.” Her family claimed to be descended from the famous Samurai clan named “Tametomo no Minamoto.” It seemed incredulous to me that one could come from such nobility. Nonetheless, the family would proudly show its clan burial site at a certain cave, which was known to be the Tametomo burial site. Even if my mother were indeed from this Tametomo line, the fact of the matter was that her family was very poor, living in a mud hut and often surviving at the point of starvation. My grandmother would go to a funeral and hide food in her kimono to bring home to feed her children. Thus, without much food to go around, it was natural for her family to urge my mother to become a picture bride, with the hopes that she would be able to send money home from a job in Hawai’i.

My mother had one daughter and two sons from this first picture bride marriage to Mr. Asato. Husband and wife both tried to earn enough money to send back to impoverished homes in Okinawa. As children arrived, they would be sent to Okinawa at an early age to be raised by Grandmother. There was no child care system on the plantations, so in order to continue working in the fields, most mothers had to send children back to the homeland to be nurtured by relatives.

My mother was so resourceful that she was able to save enough money to send small amounts to her family with the instruction to buy land. Her salary as a “weeder” was fifty cents for a ten-hour day, while her husband as a cane hauler made seventy-five cents a day.

One day while Matsuo was weeding the rows of sugarcane, she heard her babies crying from a distance. Women in those days brought their babies with them to work and left them on blankets under a tree.

When she rushed over to see why the babies were crying, Matsuo spotted a mongoose near the blanket looking at the bawling babies. She ended up laughing at what she saw. Chasing the mongoose away, she picked up the two babies and comforted them. Then she went back to work.

After seventeen years on the plantation, my mother and Mr. Asato returned to Okinawa. They owned land now, but this fact caused a big rift in their marriage. According to Okinawan custom, a man could have mistresses if he owned land. Having converted to Christianity in Hawai’i, my mother would not tolerate the presence of young mistresses in the household, especially since much of the land had been earned from her hard work and her ability to save money. The final blow arrived when her younger son died of internal injuries at a judo practice; my mother pled for her son to be taken to the hospital, but her husband refused.

This death was the last straw for my mother. She wrote to a Reverend Shimatori in Wahiawa, asking whether he could sponsor her so she could return to Hawai’i. Fortunately, he said, “Yes” and a new life lay ahead of her.

However, as punishment, Mr. Asato forbade my mother to bring her daughter, Mineko, and her son, Hiroshi, to Hawai’i with her. She was heartbroken, but she had no recourse. I cried when my mother described to me the scene at the port in Okinawa on departure day. No one was allowed to come to say “goodbye,” so Matsuo stood forlornly by herself as she waited to board the ship. Only the Christian pastor arrived in time to bid her goodbye and wish her a safe journey to Hawai’i. She arrived at the port of Honolulu on December 10, 1936 to start a new life.

The good news is that Rev. Shimatori introduced my mother to Kyozo Matsui from the Hiroshima prefecture in Japan, and then the reverend acted as their “go-between.” From Hawai’i, my mother divorced Mr. Asato, a brave thing to do in those days when wives were not allowed to divorce their husbands.

My mother married my father, Kyozo, in 1937. Thus, my father and my mother were both approaching forty when they started a new family. My sister arrived on April 20, 1939, and I joined the family on December 26, 1940. Rev. Shimatori chose for us the names Ruth Hatsue from the Old Testament and Julia Keiko from the New Testament. However, my family and the local Japanese-Okinawan community knew me by my Japanese name, Keiko. Then when I began school and entered the Euro-American world, I became known to my classmates as Julia Matsui.

While I was growing up, Rev. Hirano and his son, David, would come to our home in Wahiawa on a regular basis, representing the Holiness Church. Apparently Rev. Hirano was sent as a missionary from Japan to Hawai’i. My mom told me that Rev. Hirano was the one who converted her to Christianity. What a small world because twenty-five years later, Rev. Hirano’s son, David, and I would be working closely together on the national level of the Pacific Islander and Asian American Ministries (PAAM) of the United Church of Christ. Both of us started out as children active in the Holiness church, lost track of each other, and ended up working on various councils of the Congregational system many years later. David also experienced a lot of institutional racism while serving as head of Global Ministries but we will leave it to David to tell his own story one of these days in his own book.

Fortunately for my sister and me, there were no boys born into the family since boys were given preferential treatment in Japanese culture in those days. Instead, we were both treated with much love because it was the first family for my father and the second family for my mother.

And because our parents were no longer young, I think Ruth and I were treated almost like grandchildren. It was a blessing indeed to have mellow parents who came with a lot of life experience and wisdom.

Higa family in Kitanakagusuku, Okinawa.

Julia in purple, on a visit to Okinawa in 2011.

Higa family in Tokyo; left to right, Akiko, Junji, Derrick, Alyssa.

Leaving his village of Kobatake in Japan at the tender age of thirteen must have been very difficult for my father, Kyozo Matsui. Being the youngest son, however, Kyozo knew that he would not inherit any of the family land. Thus the words on the posters recruiting young men to work in the fields of Hawai’i pointed to a good deal and the promise of a lucrative job. Little did he know how hard the work would be as a cane hauler in the hot sun of Hawai’i. So young Kyozo set off down the mountain path and walked many miles before he reached the port near Hiroshima.

Once he left, Kyozo never looked back. When he died at the age of eighty-eight, he was totally out of touch with his relatives in Kobatake. And because he never shared any stories with Ruth and me, we knew practically nothing about his childhood. We did not have any address or letters from his family or friends—we didn’t even know the name of his village until recently.

Finding my relatives from my father’s side turned into a miracle story. I was not interested in finding my relatives in Hiroshima until a friend said it was important to know your roots and be part of your ancestors on both sides of the family.

I reflected on the “roots” issue and put it on the back burner since I did not know how to take the first step. I realized searching for my father’s family was a seemingly “impossible” task since I could not read much Japanese.

Then the miracle began. I met a Korean woman, born and raised in Japan, who was working on her degree in cultural studies and women’s studies. Yeonghae Jung enrolled for two years at UC-Berkeley to further her studies. And because she needed a place to stay, we offered a room to her and her three-year-old daughter.

We became a tight-knit family, and when Yeonghae returned to Japan, I asked her to do a little research and find out the name of my father’s village. All she had to work with was my father’s name. She wrote back and said that my father came from a mountain village called Kobatake in the Hiroshima prefecture. I was elated at this discovery and asked whether there was any possibility she could meet me at a train station in the Aichi area. The second question was whether she would be able to drive me up the mountain trail to Kobatake.

Yeonghae turned out to be my angel. Miles and miles of upward-curving roadway was a difficult drive, but after two or more hours, we reached Kobatake.

Upon arrival, Yeonghae and I were amazed at the sheer beauty of the place—clean running streams, beautiful flowers, and trees everywhere. I wondered why my father would ever want to leave such a beautiful place. It seemed even more lovely than Hawai’i. Indeed, it was my image of the Garden of Eden.

After refreshing ourselves, Yeonghae and I set out to find people who might have known my father as a youth. I had only one photo of my father, on his wedding day, plus a faded family tree called the “koseki.” My friends, who later heard how I engaged in the search, said I had so much “chutzpah” since I went from shop to shop, showing the shopkeepers my father’s photo and asking whether anyone in the area resembled him.

After several hours of no results, Yeonghae pointed to the late-afternoon sky and indicated that it would be difficult for her to drive back down the curving road at night. I begged to visit one more store and she said, “Yes, but make it short.” Amazingly, this last shopkeeper pointed down the road and said that there was a “look alike” in a nearby senior home.

Desperate for a positive outcome, I prayed that the gentleman would indeed turn out to be a relative. When I showed the photo to the receptionist at the senior home, she immediately called a room number, and in a few minutes, in walked a gentleman with exactly the same smile as Kyozo.

I told the receptionist, “This is my long lost relative!” Then we looked at the family tree and found the name “Tadami” on the chart. On this “koseki,” Tadami was listed as my father’s brother’s grandson.

Meanwhile, it was turning dark outside, so I apologized profusely to my newly-found relative, Tadami, indicating the need to get home safely to Hiroshima city.

However, Tadami insisted that he be allowed to take us to my father’s childhood home, although it was rundown and vacant. Yeonghae nodded, “Okay.” Tadami had just retired from being a taxicab driver and like a true Japanese taxi driver, he whipped himself quickly around the mountain while Yeonghae followed suit.

As we approached the birthplace of Kyozo, we saw three men standing outside the gate as though they were expecting us. Amazingly, the three men had arrived to pay their respects to their ancestors on that day and were planning to go to the cemetery to clean the family plots and place flowers there.

We introduced ourselves and discovered we were cousins. Then we quickly exchanged addresses and apologized that we needed to get down the mountain before darkness descended. We hurriedly took a photo of the three men with the abandoned home in the background.

Little did we know that thirteen years later, Ayako, the daughter of one of the men, would be living with us in Kapolei, Hawai’i, while studying English at the Leeward Community College. When Ayako’s sister, Tomoko, visited us in February 2013, she took many photos of the three of us visiting my hometown of Wahiawa. One of the men was Tokumi Matsui, Tadami’s son. Recently, Tokumi and his wife Junko spent a week with us over the Christmas holidays (Christmas 2013) in Kapolei, Hawaii. It was such a memorable experience; I marvel at how fortunate Bob and I are to be able to connect with Tokumi, Junko, Ayako, and Tomoko, long lost relatives.

Tomoko is a budding artist and I have included her art work in color. Please visit her blog at katazomeir.exblog.jp and help her to be more than a “budding” artist. She paints scenes of her father, her mother, and her neighborhood in a very whimsical style. She also did a postcard with the Tokyo Sky Tree on it because her father was one of the many engineers who made Tokyo Sky Tree possible. His story was in one of the publications from Japan, but because I cannot read the “kanji” in the book, I was not able to get the details of his contribution. Please google “Tokyo Sky Tree” and you will find many interesting stories about how it is the tallest building in Japan and possibly the second tallest building in the world. The family’s photo has been attached to this story.

This experience is part of why I have become a believer in miracles—in the power and purpose, in the unexpected twists and turns that have led ultimately to inexplicable outcomes in my life.

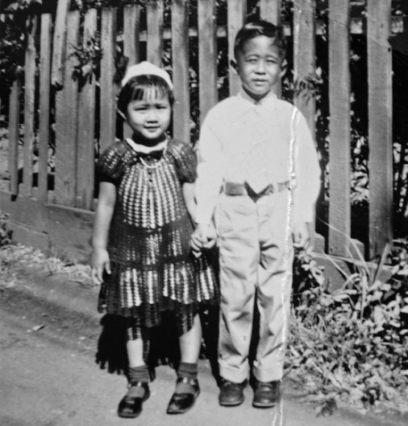

Wilfred and Amy Kusaka, children of Sensei Kusaka and Mineko Asato

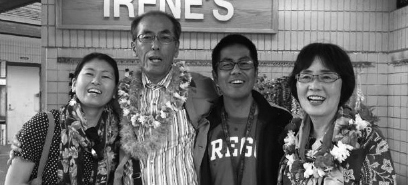

Ayako with father Tokumi Matsui, host Robert Estrella, and mother Junko Matsui during a visit to Hawai’i, Christmas 2013.

Visit Tomoko’s blog at www.keikomatsuihiga.com