Coming soon!

July & Winter: The Growing Seasons

of the Sierra for Farmers and Gardeners

Find Gary and his farmers’ market schedule

at www.sierravalleyfarms.com

Read Gary’s column,

“Chronicles of a Dirt Farmer”

at www.moonshineink.com

Check out Gary and his farm on YouTube,

“Is Sustainable Attainable?”

Copyright © 2013 by Bona Fide Books.

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Bona Fide Books.

ISBN 978-1-936511-07-5

ISBN: 9781936511136

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013934320

Cover Design: www.shearermedia.com

Copy Editor: Mary Cook

Photo Imaging/Map Illustration: Jared Manninen

Layout: www.kristenschwartz.com

Printing and Binding: Thomson-Shore, Dexter, MI

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to:

Bona Fide Books

PO Box 550278, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96155

(530) 573-1513

www.bonafidebooks.com

In Memory

Of my mentor growing up,

my twin brother, Larry Romano.

Larry would get a few laughs out of this

as only he and I could relate to our

childhood experiences on the farm.

This book is dedicated to my family

and friends, and to all the small farmers

across America who do what they do.

If this book saves one small family farm

or inspires someone to become a farmer,

it will all be worth it.

The fight to save family farms isn’t just about farmers. It’s about making sure that there is a safe and healthy food supply for all of us. It’s about jobs, from Main Street to Wall Street. It’s about a better America.

∼Willie Nelson

Introduction

Chapter 1 |

La Familia |

Chapter 2 |

Growing Up on the Farm |

Chapter 3 |

Mountain Men |

Chapter 4 |

The Metamorphosis of a Small Organic Farmer |

Chapter 5 |

Where Have All the Small Farmers Gone? |

Chapter 6 |

Set Up to Fail |

Chapter 7 |

Diversify, Diversify, Diversify |

Chapter 8 |

Meet Your Twenty-First Century Small Farmer |

Chapter 9 |

Where Do We Go from Here? |

Chapter 10 |

Why I Farm |

Appendix A |

The Corner Store Farmers’ Market: A Model for Small, Rural Communities |

Appendix B |

Resources for Small Farmers |

Appendix C |

Ten Ways Farmers Can Sustain the Family Farm in the Twenty-First Century |

Glossary

Farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil and you’re a thousand miles from the cornfield.

∼Dwight David Eisenhower

If you look around, change is happening all over the world: countries are overthrowing longtime governmental regimes, dictators are being ousted, and in the United States, 2011 was the “year of the protester,” according to Time magazine, and then came Occupy Wall Street. That’s big time! Throughout America and the world, the little guy is fed up with the systems that govern us and that we’ve had to live by. Over the past few years in the United States, we have seen demonstrations of the 99 Percent Main Street working class voicing their opposition to the 1 Percent Wall Street, who are running this country. So I thought, why not write about the 1 percent of the 99 percent, the dinosaurs in today’s workforce: America’s small farmers.

Sixty years ago, small farms (those under two hundred acres) accounted for more than 10 percent of American jobs; today, we are losing hundreds of small farms every year—the small farmer has dwindled down to a pitiful 1 percent of today’s occupations. In fact, small farmers are classified as “other” according to the US census bureau. The slogan of the twentieth-century farm was “get big or get out,” dictated by the industrial agriculture revolution after World War II. The message to the small farmer was “join us or get out of the way because here we come.” And they did just that! In came the transformers—like Dow Chemical, Monsanto, Cargill, and General Mills—that created corporate factory farms filled with monoculture and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), all fed by petroleum-based products so that they could feed us their Frankenfoods. These corporations infiltrated the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to lobby legislators, set the subsidies, and develop rules and regulations in their favor, literally kicking the little guy out.

Their biggest victory wasn’t just taking over the small farms, but also manipulating the American public by way of the media, labeling, and advertising. The corporations created a new way of advertising food products through public relations that had never been done before, all to coerce folks into buying food that wasn’t healthy or sustainable. Over the years, the public relations departments of these large corporate food conglomerates have used marketing and graphics, advertising, and faulty labeling to con the general public into purchasing their products. Authors and public figures like Michael Pollan and Michael Moore are drawing attention to the fact that the foods we are now eating are not healthy, and are contributing to our obesity, cancer rates, and other medical disorders.

In the twenty-first century, we must reverse the damage that’s been done to our food system, our land, and our occupations. We must go back to the earth, take back our farms, reeducate our children and the general public about where our food comes from, and create a positive environment to attract young and old people to farming again. But who am I to tell you what to do? I am just a small organic farmer operating in Sierra Valley, in the small town of Beckwourth, Plumas County, California. I’m not a famous author or celebrity, just one of the last 1 percent of today’s occupations—I’m a farmer. This book is my story: my opinions, my humor and satire, the sweat and blood of three generations of farming in California. At fifty-five years old, I felt it was time to tell my story—a story from the trenches of someone who has seen successes and failures, and faces an uncertain future in trying to sustain a small family farm. I’m not a scholar or expert or published author in the subject of agriculture, but I’m a survivor, and I want to share my experiences and personal views as a small organic farmer with you.

My life as a third-generation farmer has been a metamorphosis: first, I was born into a strong Italian farming family and farmed throughout my childhood; then, like many youth, I resisted the only life I had known to get an education and went into a “cocoon,” working in public service for my mid-years; next, I got a second chance to save the family farm and return to my roots; and finally, where I am now—trying to survive and find solutions to sustain the farm in the twenty-first century. The purpose of writing this book is to create food for thought and enlist farmers and consumers in a call to action. In this day and age, it is crucial to know where your food comes from and who is growing it. I want to put others in my shoes, to inspire new people to farm, and to give a chuckle to the old-timers who have gone through the same trenches as my family and me. I also want you to understand what real small farmers go through in trying to put that carrot on your plate. Not every chapter ends in a fairy tale, and there is some gloom and doom throughout the book, but real life doesn’t always present us with a bed of roses. Farming is hard work, but life is good and can be better.

There are many challenges ahead for the small farmer to overcome, and many changes need to happen in the near future for small farms to survive. Media hype suggests that people are going back to farming, but the reality is that few survive in this day and age. This occupation represents the “survival of the fittest,” and small farms must be more than fit to survive. As the owner of Sierra Valley Farms, a certified organic farm and native plant nursery located in the northeastern mountains of the Sierra Nevada range, I’ve written this book as a conversation with you. It’s straight from the horse’s mouth—there’s no sugar coating on this baby! I want you to feel my emotions throughout the book, to agree or disagree—it’s America! But most of all, I want you to think about your food and who is going to grow it in the twenty-first century.

To help you understand where I’m coming from, I begin by describing my family’s farming history, and my memories of farming as a child, to get you in the frame of mind of what it was once like. As I went into my cocoon—working in public service for seventeen years—a lot of small family farms went under. But when I got another chance to return to farming, I jumped at it, realizing in retrospect that it wasn’t so bad after all.

But times had changed.

The old ways of farming were long gone. Today, there is a lot more to farming than just growing a crop and going to market, like my dad and his father did. Now I have to be not only a farmer but also deal with advertising, marketing, and certifying myself as organic. I act as a distributor, an event coordinator, a media director, a writer, and even a “rock star” to bring attention to farming. And in spite of all of that, I still may not make it. I know us small farmers are a dying breed. In addition, I realize that my childhood was unique—not everyone comes from a farming background. Kids today have to look back to their grandparents or beyond for someone who was actually a farmer. There is a disconnect between kids today and farming—not knowing where their food is grown and who grows it. I’m hoping that my experiences, and maybe the solutions I set forth here, will trigger a local movement within communities to change the systems that strangle the small farmer. It’s not an easy task; it’s going to take policymakers, businesses, institutions, communities, consumers, and small farmers working together to change the current system and create a positive environment to attract, enhance, and protect the American small farm.

I had fun with this book. I hope you enjoy it, and I hope to write more. I’m not a professional writer, but in 1982 I self-published a trail guide on wild edible plants of San Luis Obispo County, California, and I also write a weekly editorial, “Chronicles of a Dirt Farmer,” for Moonshine Ink, an independent monthly newspaper in Truckee, California. Why I Farm: Risking It All for a Life on the Land is my story. I’ve seen the struggles of my parents and grandparents up close, along with the trials and tribulations of my fellow farmers today. I feel I have some solutions to help sustain family farms and provide our own food sovereignty. Farming under the current rules and regulations of the USDA and state departments of food and agriculture is killing the small farmer. The odds are stacked against us, and in the long run it is a slow death—suicide with a butter knife, if you will—and if nothing else, it is a lifetime of frustration from trying to make a living. But it’s the passion to farm that drives the farmer, not making it pencil out. It’s a way of life: you live it, you breathe it, you live for it, you are a farmer. You can’t learn it in school, and you can’t teach it; you have to simply be it. There is no compromise! To all small farmers in America, I walk in your shoes and thank you for what you do. Let’s stand together in this twenty-first century and go small, or not at all!

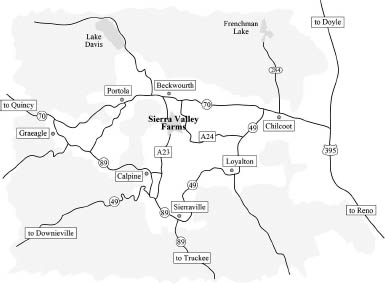

Giovanni and Bepino Romano, 1915

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.

∼Thomas Edison

The Romano Flower Farm: Redwood City, California

The oldest son of a clocksmith in Campeggi, Italy, a small town located on the Mediterranean region of Genoa, Giovanni Lodovico Romano was recruited by his younger brother Bepino (Bep) in 1915 to come out to San Francisco and help start a flower business. Only seventeen years old, Giovanni set off to the land of opportunity, America. Bep, adventurous at the age of fourteen, left Italy to find some cousins who had come to San Francisco after the earthquake of 1906. He established himself in the North Beach area of San Francisco in an Italian neighborhood and found work in the local flower industry.

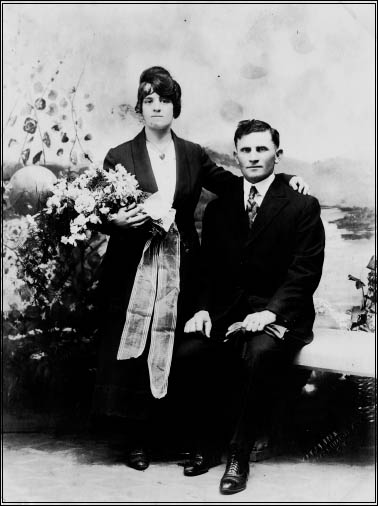

Once Giovanni arrived, the two brothers decided to try it on their own, but they were too much alike, testa dura (hardheaded) as Italians would say, so the brothers split up and started their own businesses. Bep opened the California Evergreen Nursery in Colma and later in Half Moon Bay with his younger brother Dario, who came out from Italy to become his partner in 1920. Meanwhile, Giovanni (Grandpa, or Nonno, as we would later call him) worked in the cut-flower business at the Fifth Street flower market in San Francisco for about five years and then decided to start a cut-flower operation, G. L. Romano Wholesale Florist, in Redwood City, California, in 1921. As most Italians did in those days, he wired back home for a wife, Nina, a girl he knew in his hometown. There is a running joke in the family that Grandma was a “mistake” because the wrong Nina was sent to Grandpa. It wasn’t the girl he had asked for, but he married her anyway because he said she was prettier than the girl he originally requested. Her name was Nina Maria Scanavino, a beautiful woman, and they married in 1921. Notice Grandpa is sitting in the photo, because he was shorter than Nina. That’s what they did in those days. (Heaven forbid a woman be taller than a man.) Soon after, Giovanni and Nina had two daughters, Inez and Mary, and in 1926 a son, Louis Romano, my dad. It was Nonno’s dream to have a boy to help him in the flower business, and so it became G. L. Romano & Son Wholesale Florists.

Giovanni and Nina Romano, 1921

Nonno bought three acres in Redwood City and began to farm gladiola bulbs, asters, cockscomb, and celosia as summer annual crops. He then planted perennial trees and shrubs for cut-flower production that he could depend on for income every season throughout the year. He grew early spring-flowering cherry, almond, and peach trees, and later added flowering quince and double-flowering lilacs. There wasn’t much he could grow in late fall and winter, so he looked to see what Mother Nature had to offer out in the wild. Nonno traveled the mountains throughout California and Oregon, following the seasons. Fall was a time for foliage, and he cut boughs of maple, madrone, and oak as they turned color, selling them at the Fifth Street flower market in San Francisco. During the winter, his travels took him into the foothills and mountains of the Sierra Nevada for toyon and manzanita berries, mistletoe, and Christmas trees. He was best known at the flower market for his ability to climb huge sugar pines. With a single rope and a pole pruner, Nonno cut boughs of pine limbs with huge cones on them that he would sell for a high price to San Francisco wreathmakers. The five- to six-foot-long limbs cut from the ends of the sugar pine branches had anywhere from four to eight pinecones hanging from them, each up to eighteen inches long.

A master of seasons, Nonno knew what to cut in any month of the year and sell at the flower market. While he was out in the countryside, Grandma (Nonna) was at home caring for the kids, milking the cows, making cheese and wine, and tending to the chickens. In 1933, Nonna died suddenly of a mastoid infection in her ear. My dad was only six years old, and he and his sisters carried on the farm with Nonno throughout high school, cutting flowers, doing the home chores, and working the flower market. Nonno never remarried; he raised the kids by himself, getting some help from his younger brother Dario’s family.

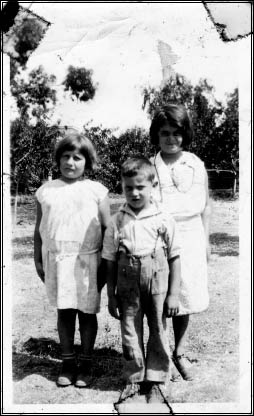

Mary, Louis, and Inez Romano, 1932

Inez and Mary got married soon after high school and moved off the farm. Dad stayed on the property to help Nonno in the flower business. Nonno had survived World War I and the Depression, and his business started to grow by the 1940s. My dad was drafted into the Navy in 1945. He returned home after a short service and then was drafted again, this time into the Marines during the Korean War in 1952, but he spent most of his time at California’s Camp Pendleton. Nonno had bought ten acres in Cupertino, California, in 1948 and began expanding the flower operation. When Dad returned from the Korean War, he settled down on the property in Redwood City.

Nonno and Louis Romano

The Bay Area was growing. There was a need for more schools, and in late 1956, Dad and Nonno got a letter from Santa Clara County that stated, by eminent domain, their land was going to be taken over for the Cupertino High School and they had to move. Eminent domain is the action of a state to seize a citizen’s private property with due monetary compensation, but without the owner’s consent, usually devoting the purchase for public use, in this case, a new school site. Santa Clara County paid a fair price, and Dad and Grandpa bought a twelve-acre ranch along Coyote Creek in San Jose, California.

The Folchi Ranch: Beckwourth, California

It all started with a dream, a dream Giacamo Folchi (Grandpa) had in 1907 when he left Ellis Island as an Italian emigrant. His dream was to be an American rancher. He wound up in Watsonville, California, then Loyalton, and worked at the sawmill. He lived for a couple of years in a small house in Loyalton before heading off on his own to become a rancher. In 1910, Grandpa Folchi wired back to his hometown in Premia (Piedmont), Italy, for a hometown girl he knew, Lucia Maria Sartorri. Upon her arrival, she was quickly informed by the local Swiss Italians that the name “Lucy” was an Indian name and that she should use her middle name, Maria; after that she was known as Maria, or “Mary.” Giacamo (Jack) and Mary ventured out on their own in 1911, homesteading their first land purchase at the old Johnny Wood place, named after the previous owner, in Carmen Valley, Sattley, California, nestled along the west side of the majestic Sierra Valley.

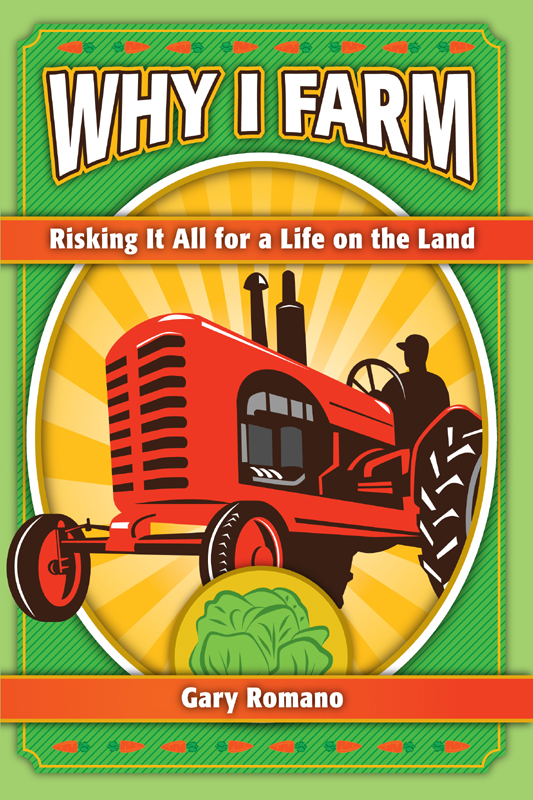

Sierra Valley is the largest alpine valley in the Western Hemisphere, encompassing over 110,000 acres, about the size of Lake Tahoe. It is situated forty-five miles north of Truckee, California, and fifty miles west of Reno, Nevada. The famous renegade fur trader Jim Beckwourth made Sierra Valley’s place in history when, in the 1850s, he discovered what would become Beckwourth Pass, the lowest pass in the Sierra Nevada mountain range, around the elevation of five thousand feet. Sierra Valley is ecologically known for its biodiversity in plant and animal life, spanning over two hundred square miles to include Plumas and Sierra counties. In the late 1850s after the gold rush, it is believed that many Swiss Italians moved from Reno to Sierra Valley to begin dairies and grain production due to the availability of water and its rich alluvial soils. Sierra Valley is a down-faulted basin, which in ancient times was a lake comparable to Lake Tahoe.

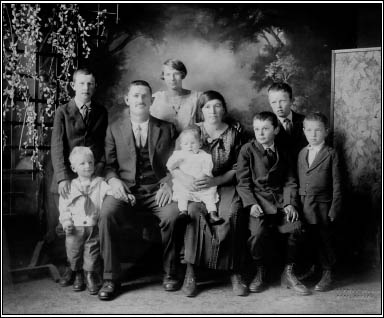

Grandma and Grandpa Folchi with their children Nina, Albert (Beno), Marion, Raymond, Emilio, Benny, and Rose.

Around 1914, Grandma and Grandpa Folchi had their first daughter, Nina, then five boys followed: Albert (Beno), Marion, Raymond, Emilio, and Benny. My mom, Rose, was the last child born, in 1924. The family lived in Carmen Valley until 1920, when they bought the Flaherty Ranch in Beckwourth, which became their permanent residence. Giacomo ran a dairy, beef, and hay operation and milked about fifty cows a day, all by hand. My grandparents continued to buy ranches along the northwest side of Sierra Valley between the town of Beckwourth and Calpine. In all, the ranches included: the Johnny Wood Ranch, Vesti Nelson Ranch, Flaherty Ranch, and the Dr. Decker Ranch, and by 1937 the Folchis owned more than three thousand acres. The Folchis survived the Depression, and the only boys drafted for World War II were Marion and Emilio, who spent three years in Italy during the war before returning home safely. The remaining brothers, Beno, Raymond, and Benny, continued to help Grandpa until his sudden death on Thanksgiving Day in 1944.

After the war and grandpa’s death, Grandma and the boys continued to work the ranches and expanded them to include cow-calf operations. Marion and Emilio got married; Marion took a job with the Plumas County road department, while Emilio worked with the brothers to carry on the ranches. The ranches now included dairy, beef cattle, hay, and grain operations. They were “working ranches”; everything was derived off the ranches. They sold milk and cream to the bigger dairies and creameries in Reno and shipped the cream by train to the Bay Area. They grew and thrashed their own grain, put up their own dryland hay, and raised their own livestock for meat production, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and poultry. They also made their own products: jerky, cheese, breads, pies, sausage, bacon, canned goods, wine, and dried goods. Electricity and plumbing came into Sierra Valley in the 1940s, and that made life easier. It was said that Grandpa Folchi was the first person in Sierra Valley to have a phonograph and radio. He liked parties and was known to have everyone over for the Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis fights.

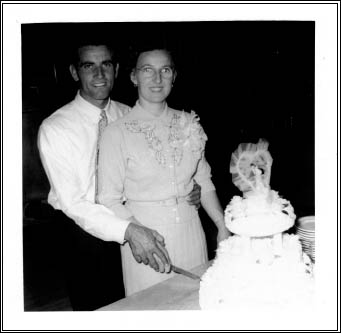

One winter around 1938, Grandpa Folchi and my uncles were out on horseback when they came upon a green pickup truck and a couple of guys cutting pine boughs from the forest. They met and had a conversation with the men, both speaking the native tongue, Italian. Instantly they became friends: Grandpa Folchi, Nonno Romano, and my dad, Louis Romano. (This became an annual event until the mid-1950s when Nonno’s arthritis limited his mobility and Dad cut the boughs by himself.) The Folchis invited my dad in for lunch. Rose Folchi was very shy, and helped grandma around the ranch with the household chores and the cooking and baking for all the brothers and farm hands. She hid behind the stove when my father came in, and would periodically sneak a peek at him. Since Rose had five brothers, the word got out that she was interested in Dad, and the rest is history. Louis and Rose married in 1956, and they moved to the Redwood City flower farm next to Nonno.

The Next Generation

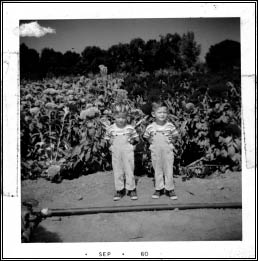

On December 7, 1957, the Romanos couldn’t have been happier when Louis and Rose had twin boys, Larry Lodovico Romano and Gary Raymond Romano (me). The Romano workforce was in place. We were the typical Italian family at that time: “la familia” came first. Parents, kids, cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents all worked, ate, and socialized together. There were no exceptions. Larry and I worked side by side with Mom, Dad, and Nonno at home, on the farm, and at the flower market as soon as we could carry a bundle of flowers to the truck (at about five years old). We were expected to contribute to the family to make a living, and spent most every weekend, summer, and holiday working at the Coyote Creek Farm. It was tough work, but hey, we didn’t know any better, and even if we did, it wouldn’t have made any difference; it was the farming life.

Mom and Dad cut their wedding cake.

In 1970, we got that infamous letter from Santa Clara County again: eminent domain wanted our land for a Department of Parks and Recreation scenic bike trail that would connect southern San Jose to Hellyer Park. So off went the Romanos, farther south, another fifteen miles, to purchase twenty acres in Morgan Hill, moving the farm and starting over for the last time.

The Morgan Hill flower farm steadily grew in the 1970s, until Nonno died in 1975. Larry and I were just graduating from high school, and we were tired of the farming life. We had missed out on a lot of childhood activities, like sports and school functions, because in the old Italian household everything was about work and helping the family business. After high school, I swore that I would never be a farmer, and that there must be a better life out there. Larry was interested in starting his own business, so he enrolled at College of San Mateo, and then went on to Golden Gate University in San Francisco, majoring in political science and business. I had always loved plants, nature, and the outdoors, so I also started at College of San Mateo, and then went on to Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, majoring in horticulture and natural resources management. I finished my education with a master’s degree from Chico State in recreation administration. Larry kept an active role with Mom and Dad in the flower business and supplemented his income with an antique business. I became a park ranger for San Mateo County Parks at Coyote Point Recreation Area in San Mateo in 1982. We both bought houses in Redwood City, and I helped Dad and Larry on occasional weekends and days off.

Times were changing in the cut-flower industry. During the 1980s, the United States began to open agricultural trade agreements with South America and Asia. We began to see large shipments of cut flowers—like roses, chrysanthemums, gladiolas, and carnations—from South American and Asian countries flood our flower markets, undercutting the growers in the Bay Area. Local flower growers could not compete, and by the late 1980s and early 1990s, I would estimate that 70 percent of the greenhouse growers were out of business. This took a toll on our flower business as well. Dad estimates that we lost 80 percent of our wholesale flower-shipping business, which was the majority of our income. On top of that, giants like Kmart and grocery chains were selling a lot of cut flowers in their grocery stores, and we lost another 80 percent of our retail business supplying the small florists that peppered San Francisco street corners, because they could not compete with these super grocery stores and were going out of business.

The flower farm could no longer support three Romano families, so I gave my business shares to Larry, Mom, and Dad. The business could no longer support the farm because the flower industry had been reduced to housewives coming in to buy cheap flowers and a few retail florists. In 1995, the Romano family decided to sell the twenty-acre flower farm in Morgan Hill so that Dad, Mom, and Larry could live comfortably in retirement. Sadly, Larry was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1995 and passed away in 1997. Dad and Mom continued going to the flower market two days a week, cutting flowers off the old farm and traveling the roadsides collecting and selling wild cut flowers until 2011.

It all came to a close in the summer of 2011. Dad, now eighty-five, said: “Well, Gary, it’s time. I’m giving up the stall that Nonno started at the flower market ninety-one years ago.”

“Are you okay with that?” I asked.

“It’s time.”

Today, Dad and Mom still cut flowers along the roadsides and from their yard in Redwood City and sell them to the outside stores at the San Francisco flower market. It’s in his blood to continue his business. I’m sure Dad will go down with a pruner in his hand someday.

Gary and Larry at the flower farm.

The Sierra Valley ranches were in full operation until 1964, when my grandmother died. The brothers continued ranching through the 1960s and into the 1970s, but times were changing there, too. Large corporate farms were buying out all the small farms. The local dairies began closing in Sierra Valley around the 1950s because the railroads discontinued the service of delivering cream down to Oakland and San Francisco and shipped only freight as they do today. By the late 1960s the dairies were all dried up. After the closing of the dairies, most of the Sierra Valley ranching operations became cow-calf, beef cattle, and hay operations.

Tragedy struck the Folchis in the mid-1970s when the youngest son, Uncle Benny, died while logging. A few years later, Uncle Raymond died of a sudden heart attack on the ranch, and then Uncle Beno went into a deep depression and ended up spending the rest of his life in a convalescent home. The only ones left to run the ranches were Emilio, his wife, Betty, and their sons Jack and David. Uncle Marion later retired from the Plumas County road department and he and his wife, Linda, moved to Reno. Emilio and Betty could not run the ranches by themselves, so they began selling the ranches off little by little. The first to go was the Carmen Valley Ranch (Grandpa’s first ranch); next was the Vesti Nelson Ranch; then the Flaherty Ranch (where Mom was born); and by 1980 all that was left was the sixty-five-acre Dr. Decker Ranch, where Emilio and Betty lived.

In a matter of twenty years, the Folchi ranches were reduced from more than three thousand acres to only sixty-five acres. Emilio and Betty’s children, Jack and David, had gone off to college. Jack graduated from Santa Clara University and landed a major job with Hewlett-Packard in the Bay Area; David graduated from San Francisco State University with a degree in communications and began working for AT&T in Oakland. By 1989 Emilio and Betty wanted to move “to town”; the ranch was too much for them to handle. That’s how I got into the picture, when I received a phone call.

“Hello, Gary, this is Betty. Emilio and I have put up the ranch here in Beckwourth for sale; David and Jack aren’t interested. Do you want to buy it?”

I had a decision to make. After swearing that I would never become a farmer after what Larry and I went through as children, growing up in a hardworking Italian family, did I want to give up my successful career in parks and recreation and go back to farming?

Only he can understand what a farm is, what a country is, who shall have sacrificed part of himself to his farm, or country, fought to save it, struggled to make it beautiful. Only then will the love of farm or country fill his heart.

∼Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Did I really want to go back to farming? In a blur, thirty years scrolled quickly through my head, with me trying to pull pieces together, like movie clips—so many experiences that I want to remember, and had never thought too much about before then. My earliest memory was sitting on the old 1958 Ford tractor under the lean-to in the backyard. I was about six years old, and I remember Dad running toward me and yelling, “What the hell are you doing?” I didn’t think I did anything wrong; I just started the tractor, that’s all. What kid wouldn’t try and start the tractor if the key was left in it?

it’s summer!