Copyright © 2012 by Bona Fide Books

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing by Bona Fide Books.

Cherry Bomb Books is an imprint of Bona Fide Books.

www.cherrybombbooks.com

A portion of the proceeds of this book will go to Planned Parenthood.

ISBN 978-1-936511-09-9

ISBN: 9781936511068

Library of Congress Number: 2012921528

Copy Editors: Elisabeth Korb and Mary Cook

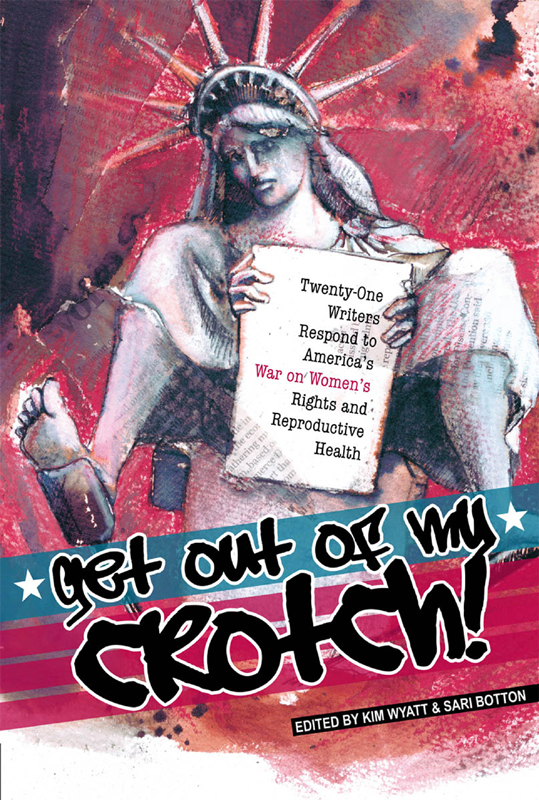

Cover Design: April Marriner

Cover Art: Shelley Hocknell Zentner

Interior Design: Courtney Berti

Printing and Binding: Thomson-Shore, Dexter, MI

Cherry Bomb Books

PO Box 550278, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96155

(530) 573-1513

editor@cherrybombbooks.com

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Alienable Rights of Women

Roxane Gay

Before Roe v. Wade

Betty MacDonald

Remember Savita Halappanavar

Katha Pollitt

Ask an Abortion Provider

Dolores P.

Confessions of a Good Girl

Sari Botton

Three Heresies

Addy Robinson McCulloch

Ripple Effect

Tara Murtha

Lucky Breaks and Little Miracles

Sarah Mirk

A Mile in Their Shoes

Kari O’Driscoll

Knocked Over: On Biology, Magical Thinking, and Choice

Martha Bayne

Endo

Janet Frishberg

Un-Bearing

Mira Ptacin

Grown-Woman Swagger

J. Victoria Sanders

Justice for All

s.e. smith

The Great Leap Backward

Camille Hayes

Birdsong and Gunshot

Rebecca K. O’Connor

Explicit Violence

Lidia Yuknavitch

Caffeine-Free Rape

Elissa Bassist

I Know Who You Raped Last Summer

Kevin Sampsell

Don’t Know Much About Biology

Kate Sheppard

Binders Full of Women, Episode 1: The Story of Mary and Bill

Rebecca Cohen

Discussion Guide

Contributors

About the Editors

Notes

Credits

Introduction

I n April 2012 I got so mad I had to do something, and I did what publishers do: I decided to make a book. Up to my neck in stories about transvaginal ultrasounds and personhood and the evils of contraception—with little meaningful regard for the people these discussions would most affect—I yelled from my desk one day “Get out of my crotch!”

“That would make a great book title,” said Mary Cook, one of the young women who work in my office.

I felt like I was living in a bizarro universe, where choice was not an option and rape meant not rape, and the patriarchy was using the last tool left to them—legislation—to limit women’s rights and agency. Each day, I grew more outraged at the attempts to erase gains made over the years by brave women and men who were asking for nothing more than equality. But it wasn’t just legislation: the powers-that-be were also trying to redefine the very language used to talk about anyone who was “other” through aggressive bills and cultural attacks. The last gasp of the white, male power structure was no longer amusing; it was dangerous.

I wanted to make some noise, to sound a call. In a fit of bewildered, angry engagement I made a list of my favorite writers and invited them to be part of this collection. When the first five said yes, I knew I was on to something. After an introduction by Roxane Gay, I invited Sari Botton on board as coeditor, and we put out a call for submissions. I was astonished at the variety of pieces received, all in response to the current political climate, in which women on birth control pills are sluts, reproductive health care isn’t covered by insurance, and the definition of rape is open to interpretation. Many of the submissions centered on personal experiences with choice, and we heard from healthcare providers committed to protecting women’s individual right to choose.

While the book began with a focus on reproductive rights and legislation, it soon expanded into issues related to gender, class, and basic human rights—we couldn’t talk about one without the other, and the writers delivered. The wild intelligence of Roxane Gay provides a doorway to the collection. Lidia Yuknavitch, Rebecca K. O’Connor, and J. Victoria Sanders illuminate the cycle of violence and its intersections with class, race, and gender, and how it is perpetuated, ultimately undermining choice. Camille Hayes, in her essay, examines why the 2012 Violence Against Women Act reauthorization stalled in Congress. Writers s.e. smith and Kevin Sampsell challenge us to expand our discussion and who participates in it.

Absurd statements about rape cost the Republicans a lot of votes in the 2012 election, and Elissa Bassist’s essay asks the reader to consider who should be defining rape. Reporter Kate Sheppard breaks down the numbers and the arguments for the heartless and faulty logic of Republican rape apologists.

We couldn’t discuss choice without looking at legislation being put forth to limit it. Reporter Tara Murtha untangles the grisly Gosnell case, and the resulting TRAP laws intended to close clinics that provide abortions, a perfectly legal procedure. In her piece, reporter Sarah Mirk takes a look at unregulated crisis pregnancy centers and their role in our nation’s reproductive health.

Our culture is also implicated in how we think about women’s rights and reproductive health: Sari Botton examines the lingering stigma of abortion, and Addy Robinson McCulloch writes about the influence of religion and how it undermines the rights of women. Mira Ptacin and Martha Bayne explore the complexities of choice in their personal essays, and healthcare providers Dolores P. and Kari O’Driscoll detail their commitment to choice for all. Janet Frishberg, writing about endometriosis, offers a rebuttal to the attack on Sandra Fluke for her reasonable objection to the high cost of birth control pills, and also addresses the lack of truly comprehensive health care for women.

Betty MacDonald details in her story one woman’s reproductive life in the United States before Roe v. Wade, getting to the heart of the book: what’s at stake and how much we have to lose. Katha Pollitt, in her essay on the circumstances of Savita Halappanavar’s death in Ireland, reminds us that we must remain vigilant, and an example for those in countries that still deny a woman’s right to choose.

Finally, the Republican Party of 2012 must be implicated: for a group espousing small government, why does it want to be so involved in the details of each woman’s reproductive system? Rebecca Cohen’s “Bill and Mary” graphic, based on religious tracts from the ’60s and ’70s, seemed comically retro until the “Binders Full of Women” meme gave it some real legs. Let’s hope it signaled the beginning of the end—and the last gasp—of this hopelessly antiquated political party.

When women have the right to choose, when they have control over their bodies, communities prosper economically, socially, and culturally. Human rights expand and civilization evolves. We all win.

The reelection of President Barack Obama means good things for the Supreme Court. But we can’t rest—attempts at regressive legislation took place on his watch, with some bills passing into law. And those invested in this legislation are organized and committed to limiting choice, redefining rape, denying women’s access to affordable health care, and generally exercising control over women’s bodies and their lives.

The writers in this book surprised and engaged me, and they helped me check some of my ideas about women’s rights and reproductive health. I hope that this collection will inspire you to expand the discussion, and make some noise of your own.

Kim Wyatt

Publisher, Cherry Bomb Books

THE ALIENABLE RIGHTS OF WOMEN

Roxane Gay

Lately, I read the news and have to make sure I am not, in fact, reading The Onion. We are having a national debate about abortion, birth control, and reproductive freedom, and men are directing that debate. That is the stuff of satire.

The politicians and their ilk who are hell-bent on reintroducing reproductive freedom as a “campaign issue,” have short memories. Of course they have short memories. They only care about what is politically convenient or expedient.

Women do not have short memories. We cannot afford that luxury.

The politicians and their ilk forget that women, and to a certain extent men, have always done what they needed to do to protect female bodies from unwanted pregnancy. During ancient times, women used jellies, gums, and plants both for contraception and to abort unwanted pregnancies. These practices continued until the 1300s when Europe needed to repopulate and started to hunt “witches” and midwives who shared their valuable knowledge about these contraceptive methods.

Throughout history, whenever governments wanted to achieve some end, often involving population growth, they restricted access to birth control and/or criminalized birth control, unless of course the population growth concerned the poor, in which case contraception was enthusiastically promoted. Historically, society has only wanted “the right kind of people” to have a right to life. We shouldn’t forget that.

Here’s the thing about history—it repeats itself over and over and over. The witch hunts, and the demonization of contraception and abortion and the women who provided these services in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, are happening all over again. This time though, the witch hunt seems to be more of a cynical ploy to distract the populace from some of the truly pressing issues our society is facing like, oh I don’t know, the devastated economy and a Wall Street culture that remains unchecked even after the damage it has done, the raging class inequalities and widening gap between those who have and those who have not, the looming student loan and consumer debt crises, the fractured racial climate, the lack of civil rights for gay, lesbian, and transgender people, a healthcare system too many people don’t have access to, wars without cease, impending global threats, and on and on and on.

Rather than solve the real problems the United States is facing, some politicians, mostly conservative, have decided to try and solve the “female problem,” by creating a smoke screen and reintroducing abortion and, more inexplicably, birth control into a national debate.

Here’s the thing about history—it repeats itself over and over and over. Women were forced underground for contraception and pregnancy termination before, and we will go underground again if we have to. We will risk our lives if these politicians, who so flagrantly demean women, force us to do so.

Thank goodness women do not have short memories.

Pregnancy is at once a private and public experience. Pregnancy is private because it is so very personal; it happens within the body. In a perfect world, pregnancy would be an intimate experience shared by a woman and her partner alone, but for various reasons that is not possible. Instead it is an experience that invites public intervention and forces the female body into the public discourse. In many ways, pregnancy is the least private experience of a woman’s life.

Public intervention can be fairly mild, more annoying than anything else—people wanting to touch your swollen belly, offering unsolicited advice about how to raise a not-yet child, inquiring as to due dates or the gender of the not-yet child as if they have a right to this information simply because you are pregnant. Once your pregnancy starts to show, you cannot avoid being part of this discourse whether you want to or not.

Public intervention can be necessary, because pregnant women must, generally, seek appropriate medical care. You cannot simply hide in a cave and hope for the best, however tempting that alternative may be. Pregnancy is many things including complicated and, at times, fraught. Medical intervention, if you’re lucky enough to have health insurance or otherwise afford such care, helps to ensure the pregnancy proceeds the way it should. It allows your fetus to be tested for abnormalities. It allows the mother’s health to be monitored for the number of conditions that can arise. If things go wrong in a pregnancy—and they can go horribly, horribly wrong—medical intervention can save the life of the mother and, if you’re lucky, the life of fetus. Public intervention is also necessary when a woman delivers her child whether by the hands of a doctor, midwife, or doula.

It is only after a baby is born that a woman might finally have some privacy.

And then there’s the manner in which the legislature, in too many states, intervenes on pregnancy, time and again, particularly when a woman chooses to exercise her right to terminate. This choice increasingly feels heretical or at least that is how it is framed by the loudest voices carrying on this conversation.

Since 1973, women have had the right to choose to terminate a pregnancy. Women have had the right to choose not to be forced into unwanted motherhood. Since 1973 that right has been contested in many different ways, but because this is an election year, the contesting of reproductive freedom is flaring hotly.

Things have gotten complicated, in too many states, for women who want to exercise their right to choose. Legislatures across the United States have worked very hard to shape and control the abortion experience in bizarre, insensitive ways that intervene on a personal, should-be-private experience in very public, painful ways.

In the past year, several states have introduced and/or passed legislation mandating women receive ultrasounds before they receive an abortion. There are now seven states requiring this procedure.

States like Virginia tried to pass a bill requiring a woman seeking an abortion to receive a medically unnecessary transvaginal ultrasound, but that bill failed. The Virginia legislature subsequently passed a bill requiring a regular ultrasound,1 in a bit of bait-and-switch lawmaking. This bill also requires that whether or not a woman chooses to see the ultrasound or listen to the fetal heartbeat, the information about her choice is entered into her medical record with or without her consent.

The conversation about transvaginal ultrasounds has been particularly heated, with some pro-choice advocates suggesting this procedure is akin to state-mandated rape. That is an irresponsible tact at best. Rape is rape. This procedure and legislation requiring this procedure are something else entirely. Although, I can assure you, a transvaginal ultrasound is not a pleasant procedure primarily because there is very little that is pleasant about being half-naked in front of strangers while being probed by a hard plastic object, at least, within a medical context. A transvaginal ultrasound is a medical procedure that sometimes must be done, but we cannot even have a reasonable conversation about the procedure and its lack of medical necessity for women who want an abortion because the procedure is carelessly being thrown into the abortion conversation as yet another distraction tactic.

Restrictive abortion legislation, in whatever form it takes, is a rather transparent ploy. If these politicians can’t prevent women from having abortions, they are certainly going to punish them—severely, cruelly, unusually for daring to make choices about motherhood, their bodies, and their futures.

In the race to see who can punish women the most for daring to make these choices, Texas has outdone itself, going so far as to require women to receive multiple sonograms, to be told about all the services available to encourage them to remain pregnant, and most diabolically, to listen to the doctor narrate the sonogram.

This legislation designed to control reproductive freedom is so craven as to make you question humanity. It is repulsive. Our legal system, which by virtue of the eighth amendment demands that no criminal punishment be cruel and unusual, affords more human rights to criminals than such legislation affords women. Just ask Carolyn Jones who suffered through this macabre ordeal in Texas when she and her husband decided to terminate her second pregnancy because their child would have been born into a lifetime of suffering and medical care.2 Her story is nearly unbearable to read, which speaks to the magnitude of grief she must have experienced.

The governor of Pennsylvania, who supports legislation in his state that will require women to get an ultrasound before an abortion, recently suggested women simply close their eyes during the ultrasound.3 They will, apparently, let anyone run for office these days, including men who believe that not seeing something happen will make it easier to endure.

Georgia State Representative Terry England suggested, in support of bill HB 954, which would ban abortion in that state after twenty weeks, that women should carry stillborn fetuses to term because calves and pigs do it too.4 Then he tried to backtrack and say that’s not what he meant. Women and animals are not much different for this man or for most of the men who are trying to control the conversation and legislation regarding reproductive freedom.

Thirty-five states require women to receive counseling before an abortion to varying degrees of specificity. In twenty-six states, women must also be offered or given written material. The restrictions go on and on. If you think you’re free from these restrictions, think again. In 2011, 55 percent of all women of reproductive age in the United States lived in states hostile to abortion rights and reproductive freedom.5

Waiting periods, counseling, ultrasounds, transvaginal ultrasounds, sonogram storytelling: all of these legislative moves are invasive, insulting, and condescending because they are deeply misguided attempts to pressure women into changing their minds, to pressure women into not terminating their pregnancies, as if women are so easily swayed that such petty and cruel stall tactics will work. These politicians do not understand that once a woman has made up her mind about terminating a pregnancy, very little will sway her. It is not a decision taken lightly, and if a woman does take the decision lightly, that is her right. A woman should always have the right to choose what she does with her body. It is frustrating that this needs to be said, repeatedly. On the scale of relevance, public approval or disapproval of a woman’s choices should not merit measure.

And what of medical doctors who take an oath to serve the best interests of their patients? What responsibility do they bear in this? If medical practitioners banded together and refused to participate in some of these restrictions, would that make any difference?

This debate is a smoke screen, but it is a very deliberate and dangerous smoke screen. It is dangerous because this current debate shows us that reproductive freedom is negotiable. Reproductive freedom is a talking point. Reproductive freedom is a campaign issue. Reproductive freedom can be repealed or restricted. Reproductive freedom is not an inalienable right even though it should be.

The United States as we know it was founded on the principle of inalienable rights, this idea that some rights are so sacrosanct not even a government can take them away. Of course, this country’s founding fathers were only thinking of wealthy white men when they codified this principle, but still, it’s a nice idea, that there are some freedoms that cannot be taken away.

What this debate shows us is that even in this day and age, the rights of women are not inalienable. Our rights can be and are, with alarming regularity, stripped away.

I struggle to accept that my body is a legislative matter. The truth of this makes it difficult for me to breathe. I don’t feel like I have inalienable rights.

I don’t feel free.

There is no freedom in any circumstance where the body is legislated, none at all. In her article “Legislating the Female Body: Reproductive Technology and the Reconstructed Woman,” Isabel Karpin argues that “in the process of regulating the female body, the law legislates its shape, lineaments, and its boundaries.”

Right now, too many politicians and cultural moralists are trying to define the shape and boundaries of the female body when women should be defining these things for ourselves. We should have that freedom, and that freedom should be sacrosanct.

Then, of course, there is the problem of those women who want to, perhaps, avoid the pregnancy question altogether by availing themselves of birth control with the privacy and dignity and affordability that should also be inalienable.

Or, according to some, whores.

Margaret Sanger would be horrified to see how ninety-six years after she opened the first birth control clinic, we’re essentially fighting the same fight. Sanger was by no means perfect, but she forever altered the course of reproductive freedom. It is a shame to see what is happening to her legacy because we are now seemingly forced to argue that birth control should be affordable and freely available, and there are people who disagree.

In the early 1900s, Sanger and others were fighting for reproductive freedom because they knew a woman’s quality of life could only be enhanced by unfettered access to contraception. Sanger knew women were performing abortions on themselves or receiving back-alley abortions that put their lives at risk or rendered them infertile. She wanted to do something about that. Sanger and other birth control pioneers fought this good fight because they knew what women have always known, what women have never allowed themselves to forget: more often than not, the burden of having and rearing children falls primarily on the backs of women. Certainly, in my lifetime, men have assumed a more equal role in parenting, but women are the only ones who can get pregnant and then have to survive the pregnancy, which is not always as easy as it seems. Birth control allows women to choose when they assume that responsibility. The majority of women have used at least one contraceptive method in their lifetime, so this is clearly a choice women do not want to lose.

The year is 2012 and here we are, having inexplicable conversations about birth control, conversations where women must justify why they are taking birth control, conversations where a congressional hearing on birth control includes no women6 because the men in power think women don’t need to be included in the conversation. We don’t have inalienable rights the way men do.

Arizona has introduced legislation that would allow an employer to fire a woman for using birth control. Mitt Romney, a supposedly viable candidate for president, declared he would do away with Planned Parenthood, the majority of whose work is to provide affordable health care for women.

A mediocre, morally bankrupt radio personality like Rush Limbaugh publically shames a young woman, Sandra Fluke, for having the nerve to advocate for subsidized birth control because birth control can be so expensive. He calls her a slut and a prostitute because in his miniscule mind, these are bad things.

What is more troubling than this oddly timed debate about birth control is the vehemence with which I have seen women needing to justify or explain why they take birth control—health reasons, to regulate periods, you know, as if there’s anything wrong with taking birth control simply because you want to have sex without that sex resulting in pregnancy. In certain circles, birth control is being framed as whore medicine, so we are now dealing with a bizarre new morality where a woman cannot simply say, in one way or another, “I’m on the pill because I like dick.” It’s extremely regressive for women to feel like they need to make it seem like they are using birth control for reasons other than what birth control was originally designed for—to control birth.

I cannot help but think of the Greek play Lysistrata.

What often goes unspoken in this conversation is how debates about birth control and reproductive freedom continually force the female body into being a legislative matter because men refuse to assume their fair share of responsibility for birth control. Men refuse to allow their bodies to become a legislative matter because they have that (inalienable) right. The drug industry has no real motivation to develop a reversible method of male birth control because forcing this burden on women is so damn profitable. Americans spent $5 billion on birth control in 2011. There are exceptions, bright shining exceptions, but men don’t want the responsibility of birth control. Why would they? They see what the responsibility continues to cost women publicly and privately.

The truth is that birth control is a pain in the ass. It’s a medical marvel but it is also an imperfect marvel. Most of the time, women have to put something into their bodies that alters their bodies’ natural functions just so they can have a sexual life and prevent unwanted pregnancies. Birth control is expensive. Birth control can wreak havoc on your hormones, your state of mind, and your physical well-being because depending on the method, there are side effects and daily worries. If you’re on the pill, you have to remember to take it, or else. If you use an IUD, you have to worry about it growing into your body and becoming a permanent part of you. Okay, that one is just me. There’s no sexy way to insert a diaphragm in the heat of the moment. Condoms break. Pulling out is only reasonable in high school. Sometimes, birth control doesn’t work. I know lots of pill babies. We use birth control because however much it is a pain in the ass, it is infinitely better than the alternative.

If I told you my birth control method of choice, which I kind of swear by, you’d look at me like I was slightly insane. Suffice it to say, I will take a pill every day when men have that same option. We should all be in this together, right? One of my favorite moments is when a guy, at that certain point in a relationship, says something desperately hopeful like, “Are you on the pill?” I simply say, “No, are you?”

Reproductive freedom has been on my mind a great deal lately. How could it not be? I’m a woman of reproductive age.

The other day, I was fuming after reading the news. With shocking clarity, I thought, I want to start an underground birth control network. Of course, I also thought, “That’s crazy. These smoke screens are just that. Things are going to be fine,” and I made a joke about starting an underground birth control railroad on Twitter. Later, I realized, the belief, however fleeting, that women might need to go underground for reproductive freedom is not as crazy as the current climate. I was, in my way, quite serious about creating some kind of underground network to ensure that a woman’s right to safely maintain her reproductive health is, in some way, forever inalienable.

When I started imagining this underground network, I had a feeling, in my gut, that women, and the men who love (having sex with) us are going to need to prepare for the worst. There is ample evidence that the worst, where reproductive freedom is concerned, is not behind us. The worst is all around us, breathing down our necks, in relentless pursuit. Either these politicians are serious or they’re trying to misdirect national conversations. Either alternative continues to expose the fragility of women’s rights.

An underground railroad worked once before. It could work again. We could stockpile various methods of birth control and information about where women might go for safe, ethical reproductive health care in every state—contraception, abortion, education, all of it. We could create a network of reproductive healthcare providers and abortionists who would treat women humanely because the government does not, and we could make sure that every woman who needed to make a choice had all the help she needed.

I spent hours thinking about this underground network and what it would take to make sure women don’t ever have to revert to a time when they put themselves at serious risk to terminate a pregnancy.

It surprises me, though it shouldn’t, how short the memories of these politicians are. They forget the brutal lengths women have gone to in order to terminate pregnancies when abortion was illegal or unaffordable. Women have thrown themselves down stairs and otherwise tried to physically harm themselves to force a miscarriage. Dr. Waldo Fielding noted in the New York Times, “Almost any implement you can imagine had been and was used to start an abortion—darning needles, crochet hooks, cut-glass salt shakers, soda bottles, sometimes intact, sometimes with the top broken off.”7 Women have tried to use soap and bleach, catheters, natural remedies. Women have historically resorted to any means necessary. Women will do this again, if we are again backed into that terrible corner. This is the responsibility our society has forced on us for hundreds of years.

It is a small miracle women do not have short memories about our rights that have always, shamefully, been alienable.

BEFORE ROE V. WADE

Betty MacDonald

My first experience with abortion is not my own. It’s 1953. My college friend Donna is pregnant.

It will be twenty years before the Supreme Court passes Roe v. Wade into law, making abortion legal. Not only is abortion illegal, so is contraception in some states. Not until 1972 does contraception become legal for unmarried couples.

I don’t think either Donna or I have any idea what abortion entails until Donna has one.

She is dating a man she calls the Industrialist. Unlike most of the men we go out with, he is not a student. From what she tells me, I gather he is a “businessman,” although neither of us knows what he does for a living.

When Donna misses her period, the Industrialist arranges for an abortion. He picks her up on a Friday night in his car, drives her somewhere in the city of Boston, and transfers her to a different car that traverses the city, ducking into streets and alleys probably to confuse her. I’m not allowed to go with her. She returns at the end of the weekend to our dorm room unpregnant. We breathe a sigh of relief. We don’t tell anyone else.

Our dorm, once a gentleman’s hotel, is a stately old stone building on Commonwealth Avenue. Each floor is divided into four suites with two doubles and one single room and one shared bathroom with a bathtub and no shower.

An elaborate open grill surrounds the old-fashioned elevator. We are allowed to come and go freely during the day, but we have to sign in at night by 11:00 or be locked out. We don’t have to present a list of approved names of men we will be dating, as do my friends who go to colleges in the South, where I’m from.

Most of the girls on our floor in the dorm are sexually active, but no one talks about it. As far as I know, no one else gets pregnant, but there are rumors.

As eighteen-year-old girls in the early ’50s (the women’s movement had not yet rechristened us “young women”), we possess very little knowledge of our bodies or reproductive lives. We know where babies come from. That’s about it.

We become sexually active in a world that offers more freedom than has been experienced before.

A world in which penicillin frees us from the scourge of syphilis, and AIDS is yet unheard of.

In that sliver of time of our sexual awakening, there are few life-threatening consequences. We choose our partners randomly and bed down when we want. It’s a time when the worst that can happen is a nasty case of crab lice or, of course, the very worst … you could get pregnant.

As I progress into adulthood I avoid serious relationships and focus on pursuing a career as an actor.

For a long time, armed with magical thinking and dumb luck, I believe I am too skinny, too anemic, or have a uterus too small or tilted to get pregnant.

After college I spend a year in my hometown, employed by the NBC affiliate writing radio copy and hosting an afternoon disc jockey show. Unscripted, I have total choice of what I say on the air and what records I play as long as I read the commercials enthusiastically. The truth is I don’t actually play the records. Because females are not allowed to touch the turntable or the control board, I share my billing with Charlie who is man enough to operate the microphones and the turntables.

I’m truly a child of the times and unaware of the sensibilities of the coming women’s movement. I don’t object because I don’t see anything wrong.

After a year on air and working in local community theatre I take the night train to New York City intent on studying acting. In the Village I become part of a group of struggling but carefree actors, artists, writers, and musicians who hang out in the coffeehouses on Bleecker and MacDougal Streets.

My boyfriend, Joel, best friends with Kevin—the one I am really interested in—has been celibate for five or six years. It is self-imposed penitence for getting his first girlfriend pregnant when he was sixteen.

When we get together, I become pregnant almost immediately. The theory is: Joel’s years of celibacy have intensified his potency. His super post-celibate sperm has overcome my magical thinking. I miss my period.

Upon the news of my condition, Dr. C., my kind GP, places me in the hands of his loyal and knowledgeable nurse. She in turn puts me in touch with an abortion provider, a doctor who makes his living renovating apartments after having lost his medical license.

Joel, always the gentleman, and the only man in our crowd with a steady job, foots the bill. The procedure is scheduled to take place in my third-floor Greenwich Village walk-up. My friend Claudette, a worldly young woman toughened by a childhood in Nazi-occupied France, offers to be with me.

The doctor, a small grey-haired, slightly disheveled looking man, having climbed the three flights to my door, first observes the apartment with the eyes of a different kind of professional; he offers a few suggestions on possible useful renovations and unpacks his physician’s bag.

My legs and butt are placed in a mesh harness because there are no stirrups on the green and buff enameled kitchen table I’m lying on.

There is no anesthesia. Too risky! Claudette faithfully holds my hand as promised. She doesn’t freak out when I start screaming and talks me through the excruciating process. When it’s over the doctor packs up and, with a few rudimentary instructions, leaves.

For weeks following the procedure I bleed and feel faint. Eventually, probably though luck and youthful good health, I heal. I put the experience behind me.

A visit to Planned Parenthood where I’m fitted for a diaphragm doesn’t protect me. I can’t insert it. I’m too embarrassed to make another appointment and get help. Insisting my partner use condoms is useless. Men think condoms cut down on their experiencing coitus fully.

Foolishly, and in complete denial, I continue to date Joel, who joins me in ignoring the fact I could get knocked up a second time.

It should probably be no surprise, then, that it only takes another few dates with Joel for his super sperm to get me again. Joel, a really good guy, feels terrible about it. Concerned and supportive, he pays for a second abortion.

This time the abortion doctor gives me instructions to meet him at an apartment in one of the many complexes in Queens. This time Carolyn, the only friend I have who owns a car, drives me through the midtown tunnel in her Corvette convertible. Before getting out of her car I swallow a pill Dr. C. has given me to deaden the pain.

My instructions are to arrive unaccompanied, so Carolyn waits outside in the car as I ascend in the elevator to the sixth floor. Just as I am about to press the buzzer at the designated apartment, a door on the other side of the hall pops open. The little doctor pokes his head out and calls to me urgently in a hushed voice, adding a scary creepiness to the situation. It’s like a spy movie.

Once on the table, I start to take a second pill Dr. C. has prescribed, but my abortionist stops me. He’s not taking any chances.

Fortunately the first pill works. It doesn’t deaden the pain but seems to remove me from the immediacy of it. I experience the procedure as if from a distance.

When it’s all over, Carolyn drives me back to West 10th Street. I break up with my hyper-potent boyfriend.

I feel restored and vow to be more careful in the future. I don’t feel damaged physically or mentally by the two procedures, except during the next few years, I black out during regular gynecological exams. When the speculum is inserted I have to be revived.

I feel lucky, as neither of my abortions were conducted in filthy back-alley settings with shady unschooled abortionists. My abortionist is, after all, a real doctor!

While the women’s movement begins to grow in the ’60s, I marry, birth two babies, break up with my husband, drop out, and move to the country to live on a farm with friends.

In 1972, assuming I am protected by a newfangled IUD, I don’t know what’s happening when I become plagued by pain and a terrible smell from down there. The clinic doctor at Albany Medical Center is less than interested. He can’t find anything wrong.

To my humiliation he takes the opportunity while I’m splayed on an examining table to allow four medical students who just happen to be there to view my lady parts as he patiently points out the various functions, an outrageous breach of privacy apparently not unusual for a clinic patient. My concern for what mysterious thing might be wrong with me is of no interest to them either.

That night, returning home to the farm undiagnosed, I’m sure I’m dying, as painful cramps take over.

In the middle of the night, in hideous pain, at my wit’s end, I seize on a long-forgotten memory of my elderly grandmother demanding a glass of warm salt water when she was experiencing terrible cramps in her legs. Following her example I drink salt water. When it eases the sharpness of the cramps and doesn’t make me throw up, I feel I’m on the right track.

Late that night, after many hours of contractions, some weird-looking tissue emerges from my body. It looks a lot like what came out of our goat after she gave birth. In spite of the IUD, I’ve been carrying a dead fetus, which explains the smell and the discomfort. The cramping abates and I sleep.

Several days later I return to Albany Medical Center to have the useless IUD removed. When I tell this doctor what happened he informs me I’m lucky; I could have lost my uterus. After delivering this dire information, he moves on to proposition me. I get the hell out of there.

Several years later I become pregnant again. I’m living a hand-to-mouth existence upstate on my own, having left the farm so my kids could be closer to their father, who lives in New York City. With few financial assets, I’m supporting my family by selling artwork, cleaning houses, and landing an occasional writing assignment.

I am totally overwhelmed. There is no way I can continue to make a living, take care of my kids, and add another baby to my responsibility. I’m aware of my shortcomings as a mother. I’m just not good at it. Another baby would be a disaster.

When I inform my boyfriend, Steve, I am pregnant and plan to abort, he sends me a book-and-a-half of food stamps as a contribution to my plight. With that kind of support, clearly I’ve made the right choice.

Thankfully, in 1974, Roe v. Wade is the law, and a women’s collective in Woodstock arranges a legal abortion in sterile, professional surroundings in a doctor’s office in Kingston. No clandestine procedures on the kitchen table, no strange anonymous apartments, no scary rides not knowing where I’m going. And yes, there is anesthesia.

As I have little money, the doctor agrees to accept artwork in exchange for the operation. When I deliver my artwork, I can’t say he’s thrilled. Upon accepting it, he informs me that most of his art collection is stainless steel and chrome sculpture, a world apart from my bas relief of Eve and the snake in the Garden of Eden rendered in baker’s clay.

Now many years later, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, I’m appalled at the current climate brought on by right-wing politicians and pundits regarding contraception, abortion, and rape. Middle-aged adult men, whose knowledge of conception and women’s bodies is on the level of a fifth-grade boy’s, make a strong case for compulsory sex education in schools.

We’ve already been through this.

We know that legal abortion has eliminated the risk of dying from botched procedures.

We know that contraception reduces the rate of unwanted pregnancies and abortion.

We know that comprehensive women’s health care has allowed women to plan their families thoughtfully, enabling them to take meaningful positions in education, arts, business, politics, and their own lives.

So many young women today know so little about where we are coming from. A few months ago, I mention a documentary I’ve seen about the life of Margaret Sanger to twenty-six-year-old Alice who does my nails.

I’m amazed when she asks, “Is that a singer?”

Following her speech at the Commonwealth Club of California on October 10, 2012, Cecile Richards, president of Planned Parenthood is asked, “Do you think young women know what it was like before Roe?”

Her answer, “They have no idea!”

It’s time to let them know!

REMEMBER SAVITA HALAPPANAVAR

Katha Pollitt

By now the whole world knows about Savita Halappanavar, the young woman who died of septic shock in an Irish hospital on October 28, 2012, after doctors refused to complete her in-process miscarriage by performing an abortion. This was not a case of choosing between the fetus and the woman—the seventeen-week fetus was doomed, and nothing could have saved it. But it still had a heartbeat, and abortion is banned in Ireland. I can’t get over the mental image of Savita’s three days of agony. Her husband described it to the Irish Times:

“‘The doctor told us the cervix was fully dilated, amniotic fluid was leaking and unfortunately the baby wouldn’t survive.’ The doctor, he says, said it should be over in a few hours. There followed three days, he says, of the foetal heartbeat being checked several times a day.

“Savita was really in agony. She was very upset, but she accepted she was losing the baby. When the consultant came on the ward rounds on Monday morning Savita asked if they could not save the baby could they induce to end the pregnancy. The consultant said, ‘As long as there is a foetal heartbeat we can’t do anything.’

“Again on Tuesday morning, the ward rounds and the same discussion. The consultant said it was the law, that this is a Catholic country. Savita [a Hindu] said: ‘I am neither Irish nor Catholic’ but they said there was nothing they could do.”1

University Hospital, Galway, where this shameful event took place, isn’t a Catholic hospital, but no matter: Ireland’s abortion law is Catholic law. Could there be a clearer demonstration that, when you get right down to it, the church does not value women, and neither does Ireland? Even a dying fetus counted for more than the life of this young, vibrant woman.