© Shane Hinton, 2015. All rights reserved.

Book design by Tina Craig

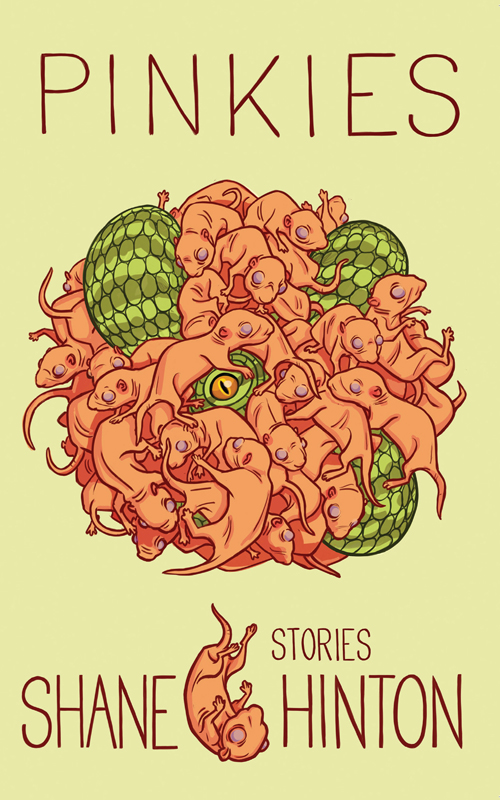

Cover art by John Hurst

Published by Burrow Press

ISBN: 978-1-941681-92-3

E-ISBN: 978-1-941681-93-0

LCCN: 2014958771

Distributed by Itasca Books.

orders@itascabooks.com

|

Burrow Press PO Box 533709 Orlando, FL 32853 PRINT: burrowpress.com WEB: burrowpressreview.com FLESH: functionallyliterate.org |

The stories in this collection were previously published in slightly different form. “All the Shane Hintons” in The Butter. “Nobody Loves Mr. Iglesias” in Word Riot. “Excision” in Atticus Review. “Never Trust the Weatherman” in Dead Mule School of Southern Literature. “Intersection” in Fiction Advocate. “Fumes” in storySouth. “Miguelito” in The Nervous Breakdown.

“If Kafka got it on with Flannery O’ Connor, Pinkies would be their love child.”

–Lidia Yuknavitch, author of The Small Backs of Children

“Shane Hinton’s Pinkies is weird, and it is wonderful. This debut collection–in which the everyday is always extraordinary–reminds me of fiction by Joy Williams and Mary Robison, and also of movies by Charlie Kaufman. If that sounds like ridiculously high praise, then good: Pinkies deserves it.”

–Brock Clarke, author of The Happiest People in the World

“Shane Hinton’s writing is terrifically smart and coolly cerebral, and full of quietly reserved, understated power. He treats the despair of the essential human condition with strength and dignity. A remarkable new young American writer, whose talent is likely to become progressively more vital and profound in the years to come.”

–Mikhail Iossel, author of Every Hunter Wants to Know

“The stories in Shane Hinton’s Pinkies wriggle with volatility. Bracingly unpredictable, they’ll slip out of your hands if you’re not careful. Here is all the absurdity and latent dread of life, but funnier, stranger, more potent.”

–Kevin Moffett, author of The Silent History

“Shane Hinton’s fiction is the visceral kind that you feel with your whole body, and it makes me want to cry through my laughing and cringing. I don’t know a better compliment to give a writer.”

–Jeff Parker, author of Where Bears Roam The Streets

For Jess, Further, Vera, and Iris, who always let me have time to do this stupid thing I can’t stop doing.

Pinkies

Pets

All the Shane Hintons

Never Trust the Weather Man

Four Funerals

Self-Cleaning

Excision

Symbiont

Miguelito

Intersection

Low Octane

Nobody Loves Mr. Iglesias

Driving School

Fumes

Bell Creek

Relapse

PINKIES

I looked at grainy black and white pictures of Jess’ insides on the ultrasound machine. The nurse held the device with her right hand and coughed into her left. “Is everything okay?” Jess asked. On the screen, shapes moved and merged into one another. It looked like she was filled up with clouds.

“You’ve got lots of people in there,” the nurse said, wiping her nose with the back of her hand.

“How many?” I asked.

“Too early to tell,” the nurse said. “I hope you have room for all these babies.”

We didn’t have room. When we got home, we stood in the hallway, looking at the doors to our two bedrooms.

“I’m going to be so big,” Jess said.

“I can build bunk beds,” I said.

“We need to start saving for college.”

We spent the evening making spreadsheets on our laptops. The budget didn’t look good. Jess thought we were being irresponsible with our debt.

The next day we went to the library and picked out stacks of novels and history books and encyclopedias, looking for names. We made a list of the names of our favorite protagonists and generals and scientists and cartographers. We reread novels that we loved when we were eighteen, but we couldn’t remember why.

We looked for names in our family trees, but weren’t sure if the dead people had been slave owners or wife beaters. I told Jess that it didn’t matter, that our babies probably wouldn’t be either. “These things are important,” she said, and we left it at that.

•

At our next doctor’s visit, I carried the list of names in my shirt pocket. It had been folded over and over and the paper was growing thin. While we sat in the waiting room, I kept touching it to make sure it was still there.

The doctor was an older man with curly gray hair and glasses. “How’s mama feeling?” he asked, poking Jess’ belly. “Must be crowded in there.”

“Some days I just can’t get out of bed,” she said.

“I’m not sure she has enough room for food,” I said. “How is she supposed to eat?”

“Is it okay to name the babies after someone who was maybe a slave owner or a wife beater?” Jess asked.

The doctor held up his hands. “I know you have a lot of questions. Having children is confusing. People are going to be pressing in on you from every side. I know all about it. My wife has had thirteen.”He listened to Jess’ belly with his stethoscope.

“Everything turned out okay?” I asked.

“We lost some of them,” he said. “It’s one of those things you don’t think you’ll ever get over, but you do. Life goes on.”

“What happened?” Jess asked.

“Oh, all things beyond our control.” He tapped on Jess’ knee and her leg shot up. “Playground accidents, python attacks. You can’t expect everything to be okay. That’s just not realistic.”

“Python attacks?” I asked.

“Yes, they’re very invasive,” the doctor said, writing something on his notepad. “Changing the ecosystem. Particularly rough on the feeble and the elderly. And small children, of course.”

Out the window, through a metal grate, I could see an old woman in a wheelchair next to a rose bush. A hospital gown was loose around her thighs. Something moved inside the rose bushes, but when I blinked it was gone. The doctor smiled. Jess stood up and stretched her back.

“Do you have any snake traps?” the doctor asked. “You might want to buy one or two, just in case.”

•

I ordered a dozen snake traps that night and chose the expedited shipping option. The website said they were guaranteed cruelty-free. The pictures showed different kinds of snakes stuck in boxes with clear glass sides: cottonmouths, rattlesnakes, black racers. The snakes were attracted to the bait and, once inside, they couldn’t find the hole again to get back out. “What are we supposed to do with them once they’re in the traps?” I asked Jess.

She shrugged.

“I don’t think we can just release them back into the wild,” I said.

After work the next day, I stopped at the pet store on the way home. They had rows of pythons in glass cages. A teenage girl with a nose ring sat behind the counter reading a book.

“What do they eat?” I asked, gesturing to the pythons.

The girl set down her book. “Pinkies,” she said.

“Pinkies?”

“Newborn mice.” She led me to an aquarium with wood shavings lining the bottom. At first I couldn’t see anything. I leaned in until my nose almost touched the glass. A pile of hairless baby mice was half-buried in the wood shavings. Their wrinkled skin blended together and I couldn’t tell one from the next. Their eyes bulged out behind thin, almost transparent eyelids. They looked like tiny dogs, sniffing the air, stretching their paws into each other’s sides and backs.

“How many do I need?” I asked.

“You got a new pet?”

“My wife is pregnant,” I said. “These are for traps.”

The girl nodded slowly. “I see. How many points of entry do you have? Doors and windows?”

I counted in my head. “Three doors and eight windows.”

“All right. A couple dozen should do you.” She reached into the aquarium, plucking out the pinkies and dropping them into a clear plastic bag. When she was done, she tied a knot in the top of the bag and handed it to me. It was full of air, like a beach ball, and the wriggling mass of pinkies at the bottom felt warm against my hand.

•

I put the snake traps next to every door and window and baited them each with two of the tiny mice. Spring was over, and as the pinkies panted, their breath fogged up the clear plastic walls of the traps.

The heat made the pythons more active. Almost every afternoon there was a new report of an attack in our area. Local preschools went on lockdown after a kid disappeared during recess. One of the news channels started referring to summer as “python season.”

A couple days after I placed the traps, I came home from work to find Jess sunbathing in the empty lot next to our house. The grass was overgrown and there were three dead trees fallen in the weeds. Perfect hiding places, I thought.

“What are you doing?” I said. “It’s python season. They’re probably out there right now, thinking how easily the little babies will slide down their throats. You know they unhinge their jaws to eat.”

“That’s sensationalism,” Jess said. “There’s no more pythons than there ever have been. You just hear about them now, with all the news coverage. They have to fill air time.”

A Fish and Wildlife Commission helicopter circled overhead. “Look,” I said, pointing up. “Why do you think they’re here?”

“Well, if there is a python, I’m sure they’ll find it.”

“Not from the air,” I said. “They blend in so well with their surroundings.”

Jess put her hand on her belly. Her skin was shiny with tanning oil and sweat. “You think a python could swallow me like this? I’m huge.” She lifted a plastic water bottle to her mouth and drank half of it without stopping.

“The news says that python attacks are up five hundred percent this year,” I said.

Jess shrugged and picked up her paperback, and we left it at that.

•

Jess’ belly grew rounder and the babies moved inside, their arms and legs making shapes under her skin. We spent a lot of time in bed, watching TV and reading books. I kept the list of names close at hand, on the bedside table, or stuck between the pages of a novel to mark my place.

One night, we selected a nature program. The British host was attractive and muscular, with a light pink scar on his left cheek. “What’s his name?” Jess asked.

“Jack Cougar,” I said, “but I think it’s a stage name.”

“Put it on the list,” she said.

In the program, Jack Cougar followed a large python around a neighborhood bordering the Everglades, using night vision to show its hunting patterns. “The pythons here in South Florida are descended from pets,” whispered Jack Cougar. “They’re not afraid of humans. They see us as a food source. People got too comfortable with nature and brought these apex predators into their homes. When the snakes grew too big, the owners released them out into the wild. Now the pythons are coming back.” Jack Cougar crept along a suburban street, poking his head over a row of hedges to get a view of a large python. The snake stopped underneath a window and raised its head up to the glass. The camera zoomed in on a small dog inside the window. “She’s hungry,” Jack Cougar whispered, “and now she knows there’s food in the house. She won’t forget. The python is a highly intelligent hunter.”

•

Glenda, our elderly next-door neighbor, stopped us two days later as we were leaving to visit the doctor. She was feeding goldfish in the small concrete pond in her yard.

“Oh, my. You’re so big,” she said to Jess. The goldfish struck at the pieces of fish food floating on the surface of the pond. “Boys or girls?”

“Some of both,” Jess said. She put her hand on her stomach.

“That’s great,” Glenda said. “We’re all looking forward to having some little girls running around the neighborhood.”

Our neighbor across the street, Bob, stopped mowing his lawn and came over to see us. “Going to have some new babies around here, huh?” he said, wiping the sweat off his forehead. “Glenda says you’ve got a whole clan in there.” He pointed at Jess’ stomach. “Oh, hey, are those snake traps? I’ve been thinking of getting some, too. I found a pygmy rattlesnake in my garage the other day. The dog almost got to it before I could.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I bought them online. They’re supposed to be cruelty-free. The doctor said we should have some to keep away the pythons.”

Bob laughed. “Go putting out those little mice and they’ll be coming around every few days for a snack before dinner.”

“That reminds me,” Glenda said. “Shane, what are we going to do about all of these cats?” A family of feral cats had moved into the neighborhood and every month or two they produced another litter. The cats fought during the night and woke us up, yowling outside our bedroom window, but I was happy that they kept the rats out of our garbage and suppressed the squirrel population. Glenda put out food for the cats every night. “I called Animal Control, but they said I have to trap them myself,” she said. “I don’t think I can do that.”

“You could stop feeding them,” I said.

“I don’t think I can do that, either,” Glenda said.

•

Nothing took the bait in the snake traps. The pinkies died and started to stink. I opened up the traps and dumped the tiny mice into the garbage can, feeling like a failure.

At our next appointment, the doctor said the babies were growing at the expected rate. “I haven’t caught anything in the snake traps,” I said. “The pinkies all died. Should we be worried?”

“Well, pythons do need live bait,” the doctor said. He flipped through pages on his clipboard, then took out a measuring string and wrapped it around Jess’ belly. “Yes, I’d like to see something in those traps. How many mice did you use?”

“Two in each trap,” I said.

“Okay. Let’s try three. Make an appointment for next week at the front desk.” He smiled. “We’ll get this figured out.”

When we got home, the neighbors were all standing in the street the way they do when the power goes out. We stopped the car in front of our driveway and asked Bob what was going on.

“Python sighting,” Bob said. “Better get mama inside.” He held a golf club in his right hand. “We’re keeping an eye on the neighborhood.”

Glenda held a large kitchen knife. “You two go on,” she said. “We’re watching out here.”

•

I went back to the pet store and the same girl was reading behind the cash register. “I need more pinkies,” I said.

“You’ve been watching the news,” she said.

“I think so. Why?”

“You look nervous. They’re just trying to keep you worked up about pythons so they can sell more advertising.”

“The doctor told us to set traps.”

The girl shrugged. “A lot of people say a lot of things.” She dug behind the counter and handed me a pamphlet. It was titled Living with Invasive Species: A Guide to Peaceful Coexistence. “Check it out,” she said. “How many pinkies do you want?”

•

I baited the traps, pinching the newborn mice at the scruff of the neck and placing them gently into the plastic boxes. I looked up guides for raising mice on the internet. That night, I went back outside and fed the pinkies baby formula with an eye dropper, one by one. They nuzzled the glass tube and sucked enthusiastically.

Later, as we lay in bed, Jess said, “I wonder what the babies will be like.”

“I think they’ll be happy for the most part, but sometimes they’ll have bad days,” I said. “That’s just unavoidable.”

“I think they’ll understand the importance of family, but won’t be burdened by the obligations of it. We’ll try not to guilt them.”

“Definitely,” I said. “When I get old, I’ll tell them, ‘Just let me die in this old house by myself.’”