STEPHANIE BENNETT is a retired Brisbane dentist, a graduate of the University of Queensland. She has four adult children and nine grandchildren. In writing this book, she has combined two of her passions – Australian history and true crime mysteries – as she did with her first book, The Murder of Nellie Duffy.

Also by Stephanie Bennett

The Murder of Nellie Duffy:

A compelling account of a legendary and brutal crime

Imperial measurements appear throughout this book as they were in use during the time the book describes.

| 1 inch | 25.4 millimetres |

| 1 foot | 30.5 centimetres |

| 1 yard | 0.914 metres |

| 1 mile | 1.61 kilometres |

| 1 chain | 20.11 metres |

First published in 2004 by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

St Martins Tower, 31 Market Street, Sydney

Copyright © Stephanie Bennett 2013

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

| Author: | Bennett, Stephanie, author. |

| Title: | The Gatton murders : a true story of lust, vengeance and vile retribution. |

| ISBN: | 9780987539526 (ebook) |

| Notes: | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

| Subjects: | Murphy, Michael. Murphy, Norah. Murphy, Ellen. Cold cases (Criminal investigation) – Queensland – Gatton. Murder – Queensland – Gatton. |

| Dewey Number: | 364.1523099432 |

Cover design by Bob Bennett.

THE GATTON MURDERS.

A True Story of Lust, Vengeance and Vile Retribution

The Lonely Road

CHAPTER 1

The Murphys of Blackfellow’s Creek

CHAPTER 2

A Day at the Races

CHAPTER 3

The Terrible Discovery

CHAPTER 4

The Investigation Begins

CHAPTER 5

Reputations on the Line

CHAPTER 6

The Man at the Sliprails

CHAPTER 7

In Loving Memory

CHAPTER 8

Letters Lost and Found

CHAPTER 9

William McNeil

CHAPTER 10

The Oxley Murder

CHAPTER 11

Born to be Hanged

CHAPTER 12

Public Contempt

CHAPTER 13

Vagrants

CHAPTER 14

Thomas Day

CHAPTER 15

The Local Aspect

CHAPTER 16

Guilty Knowledge

CHAPTER 17

A Chain of Coincidence

CHAPTER 18

Family Implications

CHAPTER 19

Execution of a Plan

CHAPTER 20

Who?

CHAPTER 21

Veil of Mystery

CHAPTER 22

Life Goes On

BIBLIOGRAPHY

At the beginning of the twenty-first century the 126 kilometre long highway that stretches between Brisbane and Toowoomba is a four-lane ribbon of macadamized smoothness along which a seemingly constant stream of vehicles hurtles in both directions, night and day. Its route follows almost exactly that of the lonely road that connected the two cities, with Ipswich between them, at the end of the nineteenth century, though now it by-passes with equal indifference both the city of Ipswich and the small farming towns and settlements dotted along the way, which once were the reason for its existence.

The old road was narrow and deeply rutted, bordered for much of its length by scarcely penetrable bush. Pitch black at night, an occasional flickering fire alongside the verge showed where water lying in a creek or gully meant that a billy could be boiled, and a camp made for the night.

Along its distant way few journeyed. A drover or two with a mob of sheep or cattle, some bullock teamsters and commercial travellers, an occasional local farmer with his family in the buggy, maybe a mounted policeman searching for some lost stock – these were the regular travellers.

A feature of the 1890s was the presence along the road of itinerants on foot heading west, away from the city, in search of work. There were travelling tinkers, scissor-grinders, magicians, peddlers, all carrying their swags and all down on their luck, looking for work or a hand-out as they trudged from place to place. Some were recently released prisoners, others were simply bad characters looking for trouble.

It was a dangerous road in those days, and even now, murder is not unknown along its way. Unfortunate travellers have disappeared in broad daylight, in spite of the heavy commuter traffic.

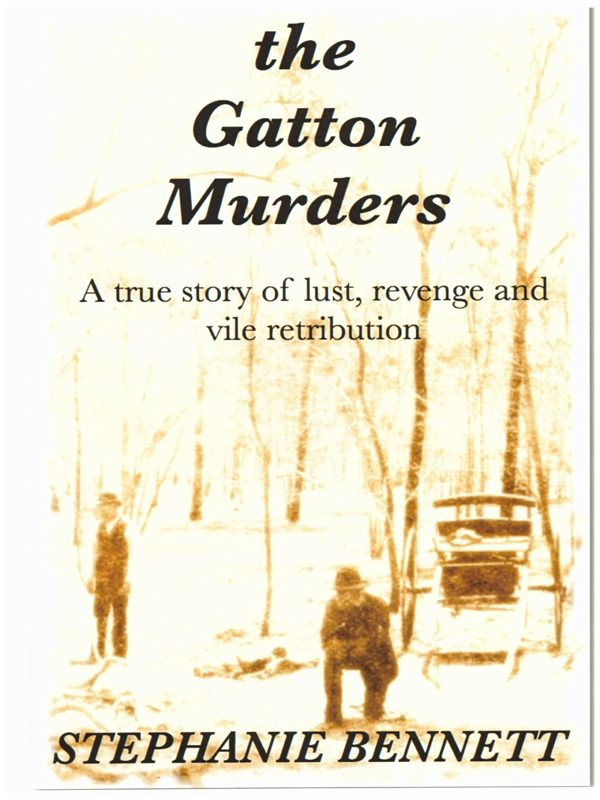

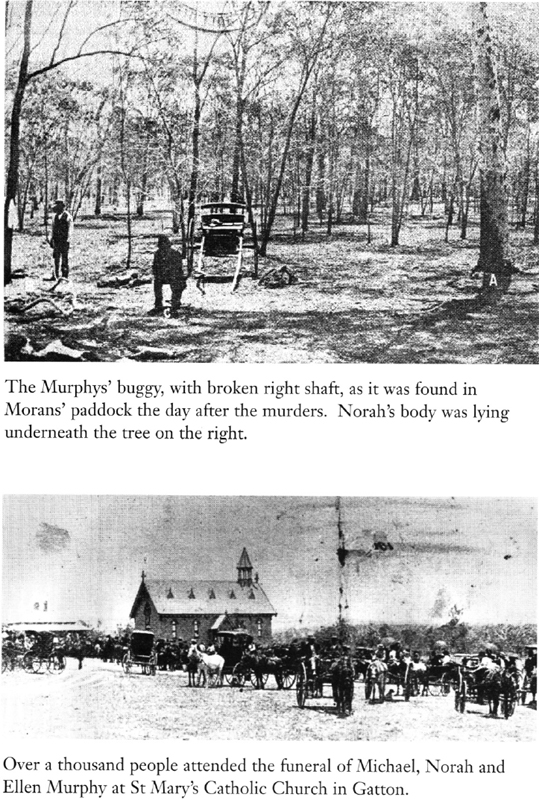

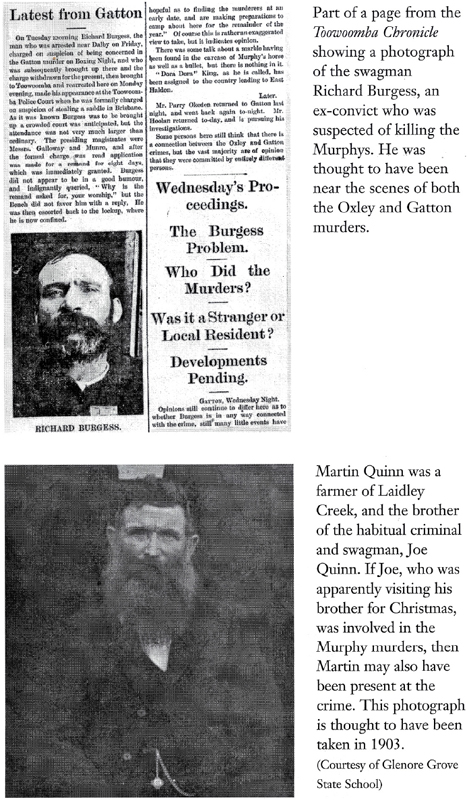

In the hot dry December of 1898 a savage murder occurred in the small farming community of Gatton, which lay along the route of the lonely highroad, about twenty-five miles east of Toowoomba. On the bright moonlit night of Boxing Day a young man named Michael Murphy was shot dead and his two sisters, Norah and Ellen, were raped then brutally murdered. The horse that had pulled the trap in which they were travelling homewards was shot through the forehead. The bodies were discovered next morning, in a paddock situated alongside the roadway, between the town and their home.

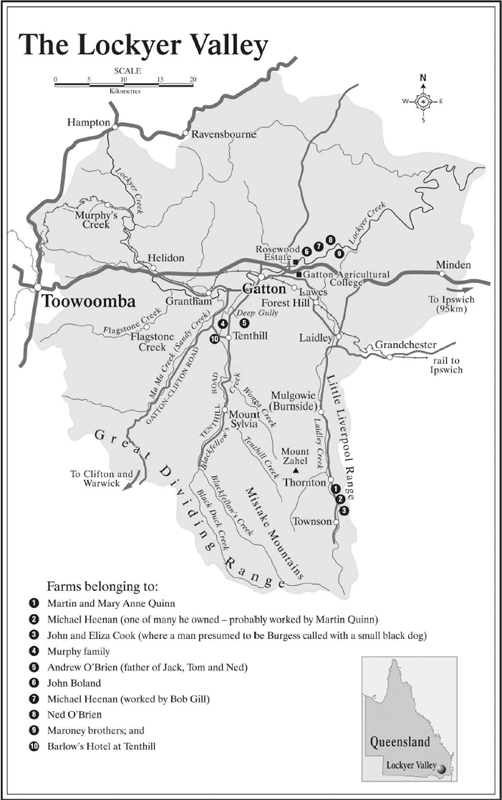

Only eleven days later, on 7th January 1899, while the community was still reeling from the shock of the Murphys’ murder, the body of a fifteen year old boy named Alfred Hill, who had been reported missing by his parents since 10th December, was found. Riding a piebald pony he had been on his way from his home at Nundah on the northern outskirts of Brisbane to visit his aunt and uncle at Redbank Plains, west of the city. The body was discovered in the lonely bush between Oxley and Darra along the highway about forty miles from Gatton. It lay concealed by bushes about four hundred yards from the side of the road, where a gully holding water and the remains of a fire indicated a camping spot. Not far away lay the carcass of the pony, still saddled, shot through the forehead.

‘Horror Upon Horror’! cried the Brisbane Courier, when the second crime was discovered.

A correspondent to ‘The Queenslander’ wrote (14/1/99): ‘When the news of the second murder reached town and the body of the poor boy Hill was found… a panic seemed to seize the people. The streets on Saturday night were thronged; all the people from the suburbs rushed into town; special editions of ‘The Observer’ were published late in the afternoon … the people insatiable in their desire for details…’

In the case of the Murphys, the police were convinced that the murder of the three victims and the savage rapes were the work of one man, a stranger to the district – one of the itinerant swagmen from the highway, passing through. It was on that assumption that the subsequent investigation was predominantly focussed.

The resources of the Criminal Investigation Bureau led by Inspector Frederic Urquhart were insufficient to conduct two major investigations simultaneously and the search for the murderer of Alfred Hill was badly bungled. The police were convinced, because of their many similarities, that there was a connection between the Gatton and the Oxley murders, but in the end they failed to solve either crime.

There were many who did not agree with the official line, and considered the Murphys’ murders to have been committed by more than one man. They believed that the killers lived locally, were known to their victims, and revenge and lust were the motives behind the crimes.

Because of the authorities’ belief in the connection between the two crimes the local investigation was treated superficially. ‘How could the Oxley and Gatton murders be connected if the Murphys were killed by locals for personal motives?’ they reasoned.

The claims of Gatton folk should have been vigorously pursued at the time, and in this re-construction of the crime will be examined thoroughly. The focus will be, not on the well-trodden ground of the police investigation, but on the area which it approached with closed minds – the local angle.

The lives of the Murphys will be exposed to scrutiny, as will the lives of their family and friends, for knowing how the victims were perceived by others and how they viewed themselves as members of the community are fundamental to an understanding of what the murders were about. It is only through an intimate knowledge of Michael and his sisters that we can begin to explain the inexplicable – what inspired the hatred of the Murphys that resulted in their horrific murder?

In the process of exploring what lay behind the terrible crime, the invasion of the personal privacy of certain long-deceased members of the Gatton and Laidley communities is inevitable. The intrusion is reluctant and implies no disrespect, but is essential to arriving at an answer to this long unsolved riddle.

Handsome and well-liked, twenty-nine year old Michael Murphy was unmarried. Employed at the Westbrook Experimental Farm near Toowoomba, he was a part-time volunteer Mounted Infantry Sergeant. He was a hard worker, and was said to be ‘highly esteemed for the faithful discharge of duty, exhibiting at all times the most conspicuous integrity.’

Norah, also single, was twenty-seven years old, and fully occupied helping her mother run the house for the family of ten mostly adult children. She was said to be admired by all who knew her.

Ellen was eighteen years old and had left school only two years previously. Her headmaster said of her: ‘No parent could have wished for a better daughter than Ellen Murphy.’

Surely none of these three people had enemies.

After the brutal murder of the Murphys, people in the community were very frightened, and many conveyed suspicions to the police through anonymous letters. In this analysis of the crime the advice contained in such letters is given credence, as are the snippets of gossip that are included in many of the depositions. Fairly or unfairly they have been accepted on the principle of ‘where there’s smoke there’s fire’. These reports, after all, originated from the Murphys’ neighbours in the little town, who knew them better than anyone else. If the Murphys were murdered for reasons of revenge, as many believed, the mainspring of the retribution must reside somewhere among the rumours and scandal, known and circulated by their close associates.

It is safe to say that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, few Australian crimes had a more profound or lasting impact on people’s imaginations, and none was more memorable for its sheer horror, than the Gatton murders. As much for the mystery that still surrounds it as for its utter savagery, the murder of the three siblings, on the clear moonlit night of Boxing Day, still stands alone.

While it will forever remain one of the most chilling and tragic episodes in Australia’s colonial history, finding a solution to the crime has, over the years, become something of an intellectual challenge for sleuths, both amateur and professional. There must be many people who have always believed that somewhere within the decaying records of the police files the answer to the mystery will yet be found. What becomes apparent after careful examination and painstaking study of the evidence, is that the behaviour on the night in question of some of the young men who lived in the neighbourhood of Gatton at the time arouses strong suspicions. The issue is not one of assigning guilt or innocence – the time has long passed when such matters could be determined. But if the movements of these men on the night of the murder had been more closely tested, and their interrogations more professionally conducted, it might have been a different matter. A clearer picture would have emerged which could have either absolved suspects of culpability or allowed them to be charged and brought before a court.

The fear which prevented many people from speaking out, and the bonds of kinship which imposed a conspiracy of silence on others, combined to thwart the police investigation. Add to these handicaps the lies told by certain witnesses, which seemingly passed the examining officers by without either recognition or suspicion, and the inquiry was bound to fail. With the entrenched views of Urquhart directing their attentions in other directions, the police paid insufficient heed to suspicions voiced by locals, which could have solved the crime.

The search for a stranger to the district who could have murdered the three young Murphys was conducted with diligence and thoroughness. It was at the local level that the investigation was deficient. Evidence was collected fairly assiduously, but never properly analysed. Flawed procedures, which meant that gaps and conflicts in evidence were not pursued, were fundamental to the failure.

As a result of the inability of the authorities to solve either the Gatton or Oxley murders or another which had occurred at Woolloongabba in Brisbane earlier in 1898, a Royal commission known as the Police Enquiry Commission was set up in July 1899. The result was a report highly critical of the implementation of the Gatton investigation and those who conducted it.

‘The McNeils are worse than Chinamen – the father is living with his daughter and the mother is a cow!’ Mary Murphy on her son-in-law’s family.

There was a frightful row when Polly, the oldest of the Murphy children, married a Protestant named William McNeil. If she had not already left home a few years previously, her furious mother would have thrown her out there and then, bag and baggage. And as if marrying outside the faith were not bad enough, she had married the man in a Protestant church! To further rub salt in her mother’s wounds, Polly produced a child a mere two months after the wedding. Bailing her up in Toowoomba where they came face to face one day, Mary Murphy flew at her daughter.

‘You are a whore, you streetwalker!’ she shrieked. ‘You lay in the dirt with McNeil before he married you! You gave up Tom Ryan, who is a robber, to join a den of thieves! The McNeils are worse than Chinamen – the father is living with his daughter and the mother is a cow!’

Bitterly unforgiving, Mrs Murphy unceremoniously cast Polly asunder, the estrangement so complete that a solicitor’s letter was sent to her on behalf of the young couple over the public humiliation to which she had subjected them. She did not deign to reply.

However, in June 1898 when Polly McNeil’s little daughter was two years old, at about the time of the birth of her second child a most unfortunate occurrence saw Polly’s circumstances change. It was said she had suffered either a stroke or a severe injury, caused by a fall out of bed, which left her an invalid, completely paralysed on the left side of her body and unable to walk. Her disability appeared to be far more serious than a mere fall out of bed could inflict, but if Mrs Murphy knew, or suspected her son-in-law of being responsible for his wife’s injuries, her misgivings were not voiced publicly. Her response to Polly’s plight was immediate. She took the children in, nursing, spoon-feeding and ministering to the tiny baby, while Norah, the second oldest of her daughters, took over the care of the little girl. While his wife remained in Toowoomba Hospital, William McNeil began visiting his children every second week-end at the Murphys’ Gatton farm about thirty miles away from his Westbrook butcher’s shop, meeting for the first time in his three years of marriage, his wife’s family. By the time Polly was released from hospital in November, a bedroom for the young couple had been partitioned off the Murphys’ sitting room. McNeil’s visits then became weekly, accepted if not welcomed into the family for the sake of Polly and her children.

Mary Holland and Daniel Murphy had each fled the grinding poverty and soup-kitchen starvation of their native Ireland in the 1860s, and arrived separately in the Queensland colony. They had brought with them the Irish Catholic deep hatred of the English and Protestants, for what was perceived as the ‘murder’ of the Irish people in the famine. Ever since the famine in the 1840s, Irish settlers had been pouring into America, but the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 put a temporary end to migration to that country. One of the first immigrant ships to arrive in the Queensland colony after its separation from New South Wales, the Mangerton in 1861, carried 261 Irish immigrants out of a total of 361½ passengers (half a passenger presumably being one who was born or one who died half way through the voyage!)

Domestic servants and labourers were in great demand in the colony, but in many cases these occupations were loose definitions of the qualifications possessed by the immigrants. Often young women who described themselves as domestic servants had never even seen the silver plate, the linen napery and the elaborate hearths and fittings which were customary in the middle class homes of their prospective employers. Similarly, the experiences of young men who called themselves ‘farm labourers’ (highly sought after in the colony), were often limited to having taken their share of the chores in a family with a pig and perhaps a cow on a tiny allotment of maybe a quarter acre.

Essential advice and financial assistance to emigrants were provided by family members and former neighbours who were already in Australia. The ones to leave were then chosen within family and neighbourhood networks by negotiation. Sending a family member from Ireland to Australia affected the livelihoods of both parents and siblings of a poor family, and who should be on the boat was a very important decision. Attempts by politicians and bureaucrats in Australia to target ‘desirable’ settlers – good horsemen and versatile workers – were generally out-witted by immigrants altering their ages and qualifications to meet the requirements of certain categories and make themselves eligible for benefits offered by the colonial authorities – for example land grants. Apparently confirmation of age and qualifications was not required, and passports had not yet been introduced.

Many families were too poor to afford the travel expenses, and money needed to be sent by relatives in Australia. The basic fare was £12 or more from Britain to Australia. Added to this was the cost of conveyance from home to the point of departure, usually Plymouth or Liverpool, ‘landing money’ for arrival and an ‘outfit’ of clothes and provisions for the voyage. These expenses could prevent some would-be emigrants from travelling, although for certain categories state assistance could be obtained. ‘Chains’ of migration were created, initiated by relatives in the colony but largely funded by the state.

By 1860 most immigrants arriving in New South Wales and Queensland had been nominated under a passage known as the Remittance Regulations, under which a resident of the colony, after paying a set proportion of the fare as deposit, could sponsor a relative or friend who met certain criteria relating to age and occupation.

Few migrants made the long sea voyage to Australia as isolated beings, but rather as part of an ongoing network of emigration embracing kinship and friendship groups from individual localities. New arrivals would find themselves living amongst the same neighbours and relatives that they had in the old country, often the old tribalisms and hatreds having been brought with them to the new land.

Daniel Murphy and Mary Holland were just two of the six thousand Irish settlers brought to Queensland in ten ships between 1862 and 1865 by the ‘Queensland Immigration Society’ founded by the Roman Catholic bishop of Brisbane, Bishop Quinn (later called Bishop O’Quinn). Mostly the immigrants were young, the men labourers, and the women, if single, domestic servants. German Catholics were also sponsored, as part of the Bishop’s ambitious plan to strengthen the church’s influence in the new country. With his vigorous promotion of land settlement, Bishop Quinn led many of his migrants to take up farming land in fertile areas of southern Queensland.

Immigrants to the Queensland colony were eligible for an £18 land grant by the Government, subject to various conditions. In the case of the Irish settlers sponsored under Bishop O’Quinn’s scheme, this had to be signed over to the church and fares repaid after arrival. There was a feeling amongst taxpayers that they were paying to enrich the Catholic Church. The Bishop’s indiscreet comment that the colony might yet be known as ‘Quinn’s land’ inflamed already existing sectarian hostility, and the society was dissolved in 1864.

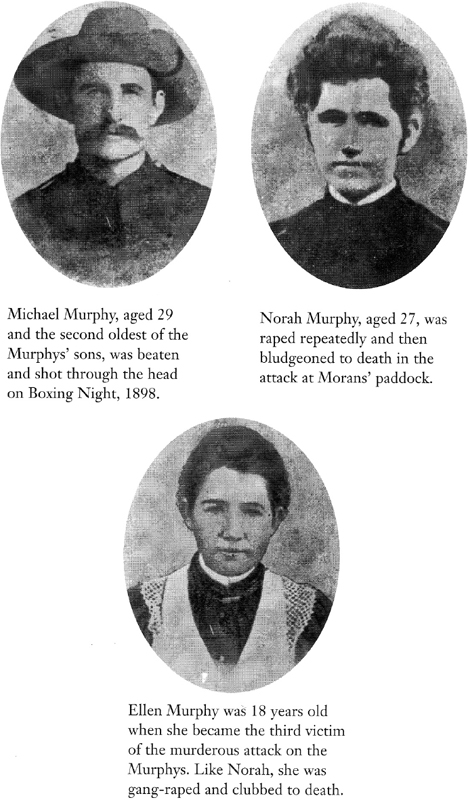

Daniel Murphy was a hard worker. Shortly after his arrival in 1864 he had obtained work assisting in the laying of the railway line between Ipswich and Toowoomba. Soon afterwards he met Mary Holland, and in 1866 the couple married.

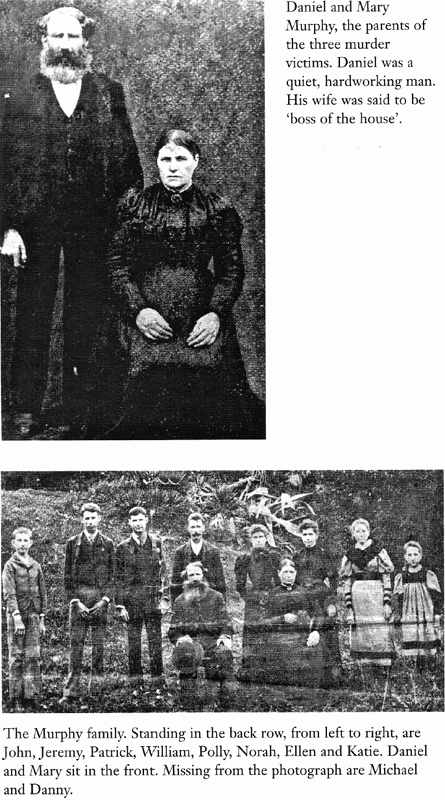

By 1898 he and Mary were the parents of ten children, six healthy and able-bodied sons and four fine daughters. Polly was by then thirty-two years old and the only one married. Next came William (thirty-one years old), then Michael (twenty-nine), Norah (twenty-seven), Patrick (twenty-four), Daniel (twenty-one), Jeremiah (twenty), Ellen (eighteen), John (fifteen) and the youngest, Catherine, or Katie as she was known to the family, who was thirteen years old. The Murphys were by then in comfortable financial circumstances, and perhaps even more importantly to them, were considered ‘respectable’ by the close-knit Irish community amongst whom they lived.

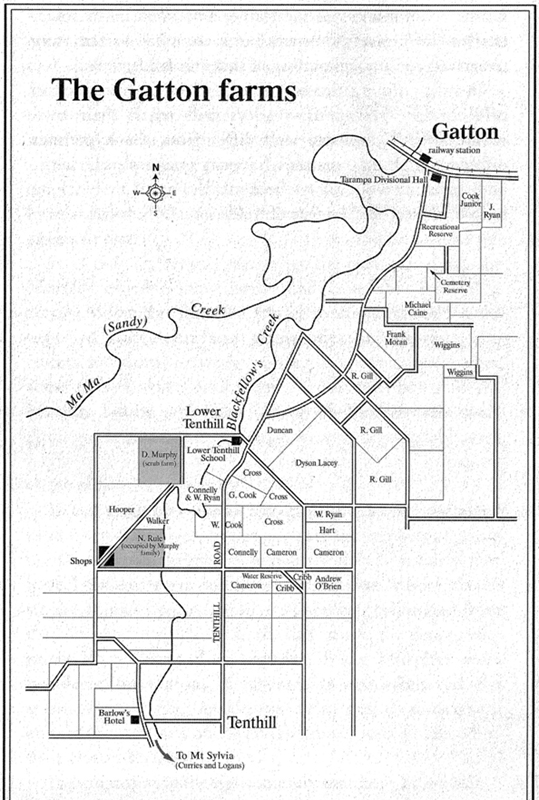

Their home was a rented farm about six miles south of Gatton. The farm’s owner was Norman Rule, the district’s Crown land agent. The farmhouse was picturesquely set in a paddock of about four acres beside the tumbling waters of Blackfellow’s Creek, a branch of Lockyer Creek. There, tea-trees and weeping willows dipped their graceful boughs in the fresh clear stream and, where the waters lay still, tall slender reeds lined the sandy banks. A track which crossed Blackfellow’s Creek near the farm gate, known as the ‘Winwill Connection’, linked the road to Gatton (Tenthill Creek Road) with the Gatton-Clifton Road which, closer to Gatton joined the Gatton-Toowoomba road.

The home was a typical low-set slab-sided settler’s cottage of five rooms, with a galvanised iron roof, a detached kitchen at the back with a brick chimney, and an open verandah at the front. Outbuildings included a stable and harness room, a barn, a hayshed, machinery sheds and cow-bails. A small pony belonging to Ellen, which was allowed to run loose in the four acre house-paddock, and an old stallion, crippled but still rideable which was kept in the stable, were the only horses kept near the house. They were used to run up from the adjacent 100 acre paddock whichever horses were required of the twenty or so that grazed there. Some of these were draught-horses, used for work around the farm. A horse-yard, where the animals were hand-fed, was connected to the house-paddock by sliprails. Willie, Jerry and Johnny, as the family called the brothers, worked the farm, their father mostly occupying himself with the recently acquired ‘scrub farm’ as they called it, almost five kilometres away. The rented farm was devoted exclusively to dairying, though fodder crops such as maize, lucerne, kaffir corn and a crop called emphee, a thin segmented sweet cane, were grown for the stock.

The ‘scrub blocks’ of about seventy-five acres or more of bush, had recently been made available to settlers, with the condition that within a certain period of time they were to be cleared and fenced. This involved an immense amount of hard physical labour with axes, mattocks and horse-drawn ploughs. Daniel Murphy’s new block was of 140 acres directly to the north of the two hundred or so acres which the family presently occupied, and was separated from it by portion of another farmer’s land. Another branch of the Lockyer – Ma Ma (or Sandy) Creek flowed through the new block.

As well as working on the rented farm the older boys contracted for fencing and roadwork jobs, just as their father had done in earlier years. Towards the end of 1898 Michael, or Mick as he was called by the family, left his job at the Gatton Agricultural College, a few miles east of the town, and began working at the Westbrook Experimental Farm outside Toowoomba. It was just across the road, as it happened, from his brother-in-law William McNeil’s butcher shop, though the two men rarely met. Pat worked at the Gatton Agricultural College as a labourer where, because it was on the other side of town from the farm, he was obliged to live during the week. Danny too, lived away from home – he was a police constable in Brisbane, at Roma Street barracks.

Daniel Murphy Senior, who was illiterate, was a quiet and very devout man. According to the Murphys’ friend and former farm-hand, Bob Smith, he ‘doesn’t read, talks little, only smokes.’ Mary Murphy, barely literate herself, was on the other hand stern and dictatorial, demanding unquestioning obedience from her children, making no concession to the fact that most of them were adults. She was, said Bob Smith, ‘boss of the house.’

William McNeil was one of a family of five sons and two daughters whose parents were old residents of the Darling Downs, where they owned a small selection at Cross Hill near Oakey Creek. He had been employed in various capacities at Westbrook Station by a Mr Jennings who had known him for about ten years. For three years he had worked for Mr Jennings as a butcher, and it was there at Westbrook that he met his future wife, Polly Murphy, a servant on the station.

In 1885 McNeil took up a selection at Westbrook Crossing where, in premises owned by him and jointly occupied by him and his brother George, he started up his own butchering business. He continued the business until November 1898, when the building, a cottage of two rooms and the shop, burned down.

It seems that on 1st November during Polly’s absence in hospital, McNeil had left the cottage at 6 pm for Westbrook Station, and about dusk George also left, to visit a shop a short distance away. Within an hour George returned to find the building ablaze.

When the burnt remains were searched the barrel of a rifle and a considerable number of empty cartridges had been found. The premises had been insured for £160, and although the suspicion was that the fire had been started by his brother, William McNeil had, on 1st December, collected an insurance pay-out of £100. He had not worked since.

‘He is more of a fool than a rogue, and cannot keep anything to himself,’ was Mr Jennings’ assessment of his former employee.

With his own house burnt down, his was a disruptive presence during his weekends at the Murphys’ home. Besides the obvious sectarian differences, Mrs Murphy looked down on him as ‘Black Irish’, that is as a descendant of the Spanish-Irish people from southern Ireland from the days of the Spanish Armada. The Murphy sons were not friendly towards him, especially Michael, and though for the most part tolerated, he was regarded as an outsider. To some extent this was inevitable for any newcomer to a large closely-knit family. The circumstances of William McNeil’s admission to the Murphys’ ranks though, and his very distinct differences from them and their hard-working strict Catholic, abstemious life-style made him completely incompatible with is wife’s family.

Embraced by the curves of Lockyer Creek, Gatton is one of the small towns lying in the lush valley which bears the creek’s name, and is the commercial centre for the agricultural produce of the region. The Lockyer Valley is actually less a valley than a fairly extensive heart-shaped plain, rimmed on all sides by mountains, some of them distant, and nourished by the clear fresh waters of the creek and its meandering branches. Along the valley to the west lies the township of Helidon, above which rises the steep Great Dividing Range. At the summit of the Main Range sits the city of Toowoomba, gateway to the rich tableland pastures of the Darling Downs, and it is in the mountains to the east of the city that the waters of the Lockyer spring. To the south-west of the valley stretch more of the indigo mountains of the Great Dividing Range. To the south-east lie the rounded hills of the Mistake and Little Liverpool Ranges where, nestled beneath their northern slopes lies the picturesque little town of Laidley, about twelve or thirteen miles in a south-easterly direction from Gatton. Between the two towns is the small settlement of Forest Hill.

The creek which flows through Laidley bears the town’s name and is another branch of the twisting, turning Lockyer. About thirty-five miles to the east of Gatton across the Minden and the Marburg Ranges is the city of Ipswich, built on a large coalfield and made prosperous in the nineteenth century by the mines. The capital, Brisbane, lies a further twenty-five miles to the north-east near the coast.

Ipswich, or Limestone as it was then called, had been opened for settlement in 1842 and in the following years the town had flourished. Prior to the separation of the Queensland colony from New South Wales in December 1859 there had been speculation that Ipswich would be named as the capital city of the new colony, but Brisbane, with its busy port close to the mouth of the Brisbane River, won the day.

Ipswich too was a busy port, with paddle-steamers similar to those on the Mississippi plying between the two cities along the Brisbane River and its tributary the Bremer, upon which Ipswich is situated. Besides coal the paddle-steamers carried to the Brisbane port processed wool from the Ipswich mill, cotton merchandise from the cotton spinning mill and local wines.

It was to protect the lucrative river business that the railway link between Ipswich and Brisbane was not built until after the Ipswich–Toowoomba link. The busy river trade came to an end after Ipswich and Brisbane were connected by rail in the 1870’s.

The line that connected Ipswich and Toowoomba passed through the towns of the Lockyer Valley. The advent of the railway and the immediate clamour for land caused the resumption of pastoral lease land to begin in 1868. It spelt the end for eight large runs in the valley, including ‘Franklin Vale’, the ‘Rosewood’ and ‘Grantham’ runs owned by Vanneck, ‘Tent Hill’, ‘Laidley’s Plains’, ‘Rosevale’ and ‘Buaraba’. Times were changing. It was only two decades since Aboriginal attacks in the valley had been commonplace.

The advent of the railway and the subdivision of the large runs saw an increase in the population of the valley, Gatton’s town residents numbering over four hundred by 1898. The district’s population of about seventeen thousand consisted mostly of Irish, English and German settlers, with little or no fraternisation occurring between those of different nationalities or religious beliefs. Many of the settlers, like the Murphys, were established on dairy farms or small crop holdings, producing from the rich chocolate earth lucerne, maize and root crops such as potatoes and onions, as well as oranges and grapes. Local wineries produced high quality wines. On the larger selections beef cattle were grazed.

The Irish community by then was presided over in the spiritual domain by their parish priest, Father Daniel Walsh, an Irishman who had arrived in Gatton in 1887 at the age of twenty-nine years. He was said by his Bishop to be ‘autocratic in the manner of the Irish clergy … direct in approach … a sincere and humble man who gained the confidence and reverence of the people of the district.’ He was well known among the entire community, not just his own flock, for his many kindnesses and acts of generosity, and for the breadth and tolerance of his outlook.

Father Walsh’s faith was to be sorely tested over the terrible events to come, and his health was to suffer severely.

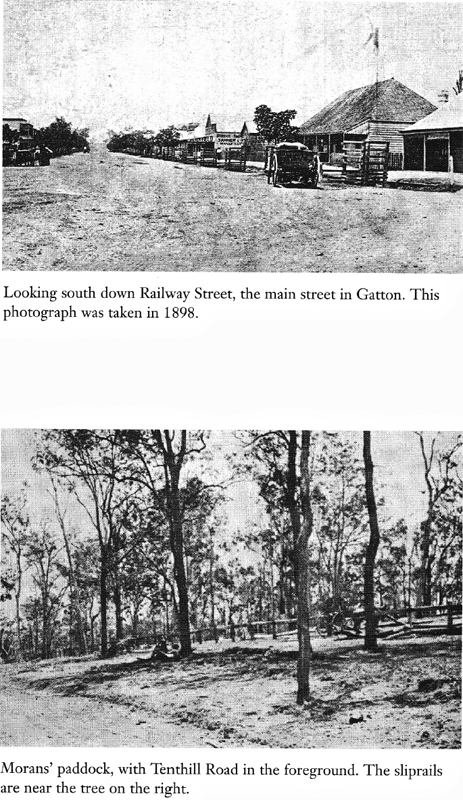

The main street of Gatton, which led at its northern end to the station, was called Railway Street, and was a wide, rough unpaved thoroughfare, unlit at night except for the flickering kerosene lamps which lit the front verandahs of hotels during evening opening hours. Wooden tree-guards protected young trees planted along the street’s borders. Single storey cottages with picket fences and shingled roofs lined both sides of the street as well as shops, businesses and hotels, each with its colonial style awning and the same shingled roof as the houses. Most of the houses had rainwater tanks or wells, or perhaps both. There were three hotels in Railway Street, and probably several sly-grog shops.

Railway Street ended opposite the station in a T-junction with Crescent Street, and was crossed further down, first by North Street, then by Spencer Street which brought traffic into the town from the east, and lastly by Cochrane Street.

The southern end of Railway Street beyond Spencer and Cochrane Streets led south to Tenthill and Mt Sylvia, the main road veering off to the west not far outside Gatton to Helidon and Toowoomba.

The railway station was a slab-sided building of typical colonial design with a covered verandah at the side, a bungalow style shingled roof with a chimney at its peak and an awning over the raised platform. Along the platform were displayed advertisements for Pears soap, Dewars Whiskey and other commodities. For the young people of Gatton the railway station had become one of the main venues for socializing. There they would congregate to greet or farewell visitors from nearby towns or simply drop by, especially when trains were due, to share a joke and a gossip with friends.

Adding to the station’s attraction as a meeting place was the music provided at certain times from the bandstand beside it. Friendships and courtships amongst the young had previously been restricted by the distance a horse could travel and return its rider safely home by nightfall. The advent of the railway had seen the station become one of the focal points for the social life of the town’s young and single.

Gatton was a lively town. Many of its inhabitants were young immigrants, and the earlier settlers of one or two decades previously had produced large families. There were plenty of opportunities for social activities, especially for the young. For example there was a cricket club, the members of which would often ride forty miles or more for weekend matches. Mr James the chemist was the organizer of a tennis club, and anything to do with farming, such as ploughing competitions, corn-husking competitions, wood-chopping, etc was strongly contested at special events.

There was a show-ground and a race-track – dog racing was very popular, particularly with Father Walsh. Dances were regularly organized and well attended and for the more sedate, fishing was a popular pastime, with plenty to be caught in the creeks, especially jew and perch.

For mothers and their daughters, competitive needlework, crochet work, knitting, dressmaking and cooking (jams, pickles and cakes) were the main relaxations. Most of a family’s clothes were sewn in the home. If the females of the family were untalented in that direction (or had no time!) travelling seamstresses and milliners were available who would move in, sometimes for six weeks, to make clothes, often to last for the next twelve months. Some seamstresses travelled with a sewing machine in a wagonette. Fabrics could be purchased at Goldman’s store, where they had been obtained from Brisbane wholesalers such as Thomas Brown in Eagle Street, or even from retailers such as T. C. Beirne in Fortitude Valley. Some people preferred to make shopping expeditions to either Ipswich or Toowoomba to purchase their clothes ready-made, Laidley people usually travelling to Ipswich and Gatton people to Toowoomba.

The valley air was crystal clear and pure, tinged with a mixture of aromas – burning eucalyptus leaves, the spicy dusty scent of newly cut chaff and the earthy fragrance of freshly tilled soil. The area was blessed with a profusion of countless varieties of bird-life, and the silence of the bush was broken by their songs.

The town itself consisted of only a few streets at that time and was mainly confined to the area between Cochrane Street, the railway line, William Street and the creek. Since 1867 with the opening of the railway line the town had gradually moved down to the area near the station, from the top of the hill where it was first established.

In the town the atmosphere was far less pleasant than in the areas surrounding it. The air was tinged with a malodorous blend of horse and cow manure, pig dung from the loading pen by the station and human nightsoil, the latter disposed of by residents in their own yards. The putrid stench of water sullage, decaying rubbish and smoke from the wood-stoves in the cottages contributed to the tainted mix. Flies were everywhere, both inside and outside. Food quickly became fly-blown, meat in summer needing to be salted immediately it was killed. Hygiene, even at a personal level, was not a high priority and deaths from such illnesses as gastro-enteritis and typhoid, especially of infants and children, were common.

Gatton was not unique in its insalubrious living conditions, all small towns and many areas of large cities sharing exactly the same environment. Barely two years were to pass before plague swept through Brisbane and other parts of the colony killing hundreds of people, including in 1902 the Government Medical Officer Dr Wray, whose role as official medical examiner during the investigation into the Gatton murders will be mentioned in this narrative.

The young Murphys’ friends were the children of the other large Irish-Catholic families in the district. Mrs Murphy had lost the battle where Polly was concerned, but she was determined that none of her other children would shame her in such a way. Fear of their mother’s rages kept them all toeing the line, their social lives, or at least those of the girls, strictly controlled and severely restricted to what their mother would allow. Church at least once a week and when possible more often, was part of their lives. Their father had long since escaped into the comfortable isolation of his religion and had taken no part in the upbringing of the family for many years. He was a gentle man and to take the line of least resistance and switch off from what was happening around him was his escape. During the day he worked alone at the scrub farm. In the evenings he sought seclusion through prayer.

Sectarianism was alive and well in the valley and had been worse since the 1870s, when Father Andrew Horan, Bishop O’Quinn’s nephew, was assigned to the Ipswich Mission, which had been opened in 1849. He was said to be ‘vigorously Irish, which only served to heighten the Orange/Green tension… This tension had been an undercurrent running through Ipswich since 1861, breaking into open hostility on several occasions.’

With a limited number of Catholic families in the district from whom to chose a partner and with few venturing far from home in search of one in spite of the railway, there were multiple inter-marriages amongst the families deemed suitable, many of them former neighbours from Ireland. Tangled networks of complicated relationships developed among the large families of ten or twelve children which saw many of the younger people with tribal loyalties as cousins, in-laws and often both, to countless others. Multiple marriages often occurred amongst the siblings of suitable families, and cousins marrying cousins was another frequent occurrence. Amongst them the gene pool may have been limited but marrying outside their faith was unthinkable. It is easy to believe that at least some of these marriages were promoted or arranged by Father Horan at the Ipswich Mission, who made it his business to be acquainted, through his travelling curates, with the welfare of every single one of his parishioners. On their return from visits to outlying parts the curates would be closely questioned on the details of each parishioner’s existence.

A good many of the parents were, like Daniel and Mary Murphy, illiterate and limited in their outlook by their ignorance. Their children were educated to primary school standard at the local state school which had been established in 1873, many commencing their schooling at quite advanced ages. Education, which was not compulsory, was often interrupted by essential farm work or by the need to keep marauding wildlife away from the paddocks all night. After completing their education, most of the young men earned their living from the soil as farmers and labourers, though some joined the railways or the police force. The girls either remained at home helping their mothers run the house for their large families, or else went into paid domestic service.

Letter writers to the press during 1898 criticized what they described as the lawlessness of the district, mentioning a stolen safe that had been blown open and the mutilation of a police horse and other animals. Crime flourished and went uninvestigated, and gangs roamed freely, undisciplined and unpenalized.

Larrikinism in the community was a widespread problem in the late 1890s, in both city and country. Mobs of up to twenty or so young men travelling in packs on horseback would set upon people (frequently those who were the worse for liquor), and would destroy property and generally terrorize the community. In country areas footbridges and other public infrastructure were destroyed or vandalized. One correspondent to the Brisbane Courier, describing the state of things in farming districts between Ipswich and Toowoomba wrote:

‘… The police officers seem content to stay quietly in whatever little township they are stationed instead of paying at least an occasional visit to the surrounding parts and breaking up these bands of country larrikins, many of whom are the sons of so-called respectable people. Alone, these hoodlums will hardly look a person in the face, but when in the mob they become insulting and dangerous, preferring the cover of darkness for their ignorant doings.’

Another correspondent supplied this disturbing anecdote of an incident in Gatton:

‘As … proof of the wild tendencies of bush larrikins I give the following facts: Some time ago two elderly persons – friends of mine – were met at the railway station … and were being taken in their host’s trap to his house. But on the road they unfortunately met a mob of young heathens, who at once set upon them and did all they could to upset or smash the trap by forcing it against fences, stumps and trees. This was carried on for a long time, until the trap stuck fast between two trees. Then the hoodlums howled and sneaked off. The owner of the trap, although he knew some of the larrikins, was afraid to lodge a complaint against them …’

Yet another correspondent was more specific in apportioning blame:

‘The respectable portion of the Irish population have for years been in fear of their lives.’

It was unreasonable to blame police officers for ‘staying quietly in whatever little township they are stationed…’ The local police station in each town acted as the agents for most government departments and for the payments due for such matters as licenses, fines, registrations of births, deaths and marriages … The list was endless and the paperwork required must have been horrendous.

Advice from Gatton Constable Lowe to authorities as long ago as three years previously was that both Patrick Ryan of Mt Sylvia and Patrick Quinn ‘belong to the notorious Ryan gang who have infested Blackfellow’s Creek for a number of years. They are the terror of peaceable settlers,’ he reported, ‘and are supposed to have had a hand in every specie of villainy and outrage committed in their neighbourhood, and are strongly suspected as cattle-stealers. The Ryan gang number about a third of the population …’

The examples of lawlessness and criminality set by their elders and the blind eye turned by police doubtless encouraged criminal behaviour and a contempt for the law amongst the younger members of the community.

The summer of Polly’s return home had been particularly hot and dry, and in the days leading up to Christmas most of the colony was experiencing a severe heat-wave. With no rain and with daytime temperatures soaring to record levels, the usually lush valley was tinder-dry, crops withering in the parched ground and businesses in the town struggling to survive. In the unrelenting heat, work on the farms was even more laborious than usual. No doubt the approach of the festive season was anticipated in the Murphy household with relief, as well as with pleasure at the prospect of the holiday and the family gathering that was to take place. Only young Constable Danny Murphy, who was unable to obtain leave, would be absent from the farm at Blackfellow’s Creek to share the family’s celebrations.

Michael Murphy and William McNeil were not on good terms – there had been trouble between them on more than one occasion. Perhaps the Murphys’ happy anticipation of the forthcoming holiday season was tempered with a little anxiety at the prospect of McNeil’s possibly disruptive presence.

Accommodating the large Murphy family presented a challenge at the best of times. Their sleeping arrangements were something of a ‘first come, first served’ or ‘musical chairs’ variety, depending on who was home at the time. An insufficient number of beds in the house obliged some in the family to share with their siblings, and if any of the boys brought friends home, they slept together.

In Ireland, poverty often compelled families to share beds, but in their new country Mr and Mrs Murphy no longer suffered from financial hardship. It is puzzling why beds were not provided for all their offspring, for the sake of comfort, if not for privacy. Perhaps the size of the bedrooms, usually about eight feet square, was a factor.

There had been three, and were now four bedrooms in the house. The McNeils’ room, which was entered through the sitting room, contained one three-quarter sized bed which the couple shared with their little girl. Mr and Mrs Murphy’s bedroom was on the opposite side of the sitting room, where the baby, now seven months old, slept in its cradle, and from it the Murphy sisters’ bedroom was entered through a curtained opening in the rear wall of their parents’ room. Another door to the girls’ room opened from the back passageway and could be bolted inside their bedroom. The one bed in this room was shared by all three sisters, although when McNeil was away Ellen shared the three-quarter bed in their room with Polly and the two-year-old girl. The boys’ room was directly behind the McNeils’ room, William’s bed lying along the other side of the partition against which the McNeils’ bed was placed. Both the girls’ and the boys’ rooms were built on what had once been a back verandah. They were called ‘skillion’ rooms, the roof over them being an extension of the main roof of the house. The passageway between them led at one end to the back entrance, and at the other, into the sitting room. A door from the passageway into the boys’ room, opposite their sisters’ door, had no bolt. In this room were three beds shared by Willie, Johnny and either Paddy, Mick or, if he were visiting, their friend Bob Smith. Jerry shared an outside bed off the kitchen with Danny when he was home. Willie and Johnny sometimes slept on the front verandah if there was nowhere else to sleep.

It was Mrs Murphy’s proud boast that none of her children had to sleep outside in the barn.

Saturday was Christmas Eve, and Pat was the first of the family to arrive home. He had about nine miles to ride from the college. On his way through Gatton he had visited a shooting gallery, a popular arcade where the young local men engaged in target practice and competition shooting. There he had encountered some friends who invited him to bring his sisters, Norah and Ellen, to a dance they were arranging in the town for Boxing Night. Pat promised to ask them. His brother Jerry, after attending church, was also at the shooting gallery that evening and the invitation was repeated to him by the boys’ mutual friends, Edwin Chadwick and the Jordan brothers.

William McNeil was next to reach the farm, driving down the mountain a blue horse in a small, rather rickety cart with only two wheels, one of them wobbly, and a broken right shaft tied together with rope. On his way he had stopped at Helidon, where he too was asked by a friend to pass on an invitation to Norah and Ellen. This one was for a dance in Helidon on Boxing Night. Mrs Murphy, on hearing of it immediately declined the invitation for the girls.

It was not until about 10 pm that Michael arrived home, riding a bay horse he intended to race at the Mt Sylvia meeting on Boxing Day. He was met at the farm gate by his brother William, who was waiting for him. When Jerry arrived home from Gatton later he found Michael sitting alone in the kitchen in front of the fire. Michael had carried with him from Toowoomba two gifts from McNeil – for Norah a lady’s bridle, and for Ellen, a lady’s whip. There were no presents from William McNeil for either young Katie, or for his mother-in-law who, in her generosity had opened her home to him and his family. Neither were there presents for his bed-ridden wife or their children.