© 2014 Albatross Förlag AB

www.albatrossforlag.com

ISBN 978-91-981867-2-7

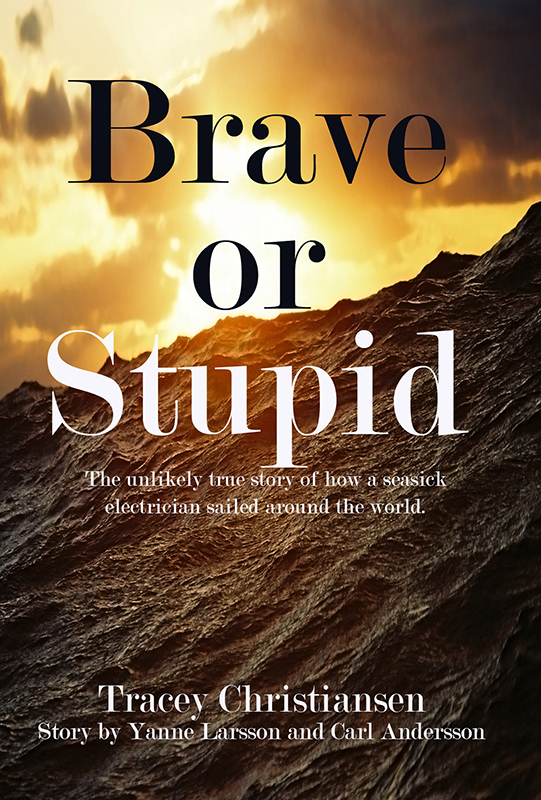

Authors: Tracey Christiansen, Yanne Larsson and Carl-Erik Andersson

Editors: Anita Larsson, Steve Strid

Graphic production: Brun Media AB

Cover by Steve Strid

Printed by CPI

www.braveorstupid.com

Contents

1. The Ghosts of Omaha Beach

2. Auf Wiedersehen Berlin

3. Not over the Hill … Yet

4. So We Bought a Boat …

5. Losing our Virginity

6. Landlubbers No More

7. The Things we do for Love

8. And So We Bought a Bigger Boat

9. Liveaboards

10. Testing Our Metal

11. So Which Way Round?

12. Worse Case Scenarios

13. Anchors Aweigh!

14. First Man Overboard

15. In Search of Nessie

16. Whisky Galore!

17. Guinness is Good for You

18. Brown Boxer Sailing in the Bay of Biscay

19. Viva España

20. Pilgrims and Prawns

21. Tales of the River Bank

22. Unhappiness on the Happy Islands

23. Crossing the Pond

24. Chilling Out in the Caribbean

25. Small Islands, Big Changes

26. Trials and Tribulations in Tobago and Trinidad

27. Beer, Bullets and Beautiful Women

28. Pictures in the Sand

29. Red Devils and Baywatch Boys in the White Man’s Graveyard

30. Paving Paradise

31. Staggering in Darwin’s Footsteps

32. The Coconut milk Run

33. Crazy Pigs in the Land of Men

34. Catching Crabs in the South Seas

35. Beers with Fu Manchu

36. Savage Islands, Friendly Islands, a Coconut and a Kingdom

37. And then all Hell Breaks Loose …

38. Love in the Land of the Long White Cloud

39. Cannibals and Crooks in the Garden of Eden

40. Reasons to be Cheerful in the Land Eternal

41. Teeth, Tentacles and a Tornado Down Under

42. A Paper Boat on the Indian Ocean

43. Politics on the Sleepy Isles

44. Rugged Beauty in Reunion

45. Wind, Waves, Water and an Albatross

46. Learning to Tackle in the Fairest Cape

47. In Search of the Giant Squid and Life Among the Saints

48. Fifty Shades of Green

49. Show me the Way to the Next Whisky Bar!

50. Homeward Bound

Postscript – Home from the Sea

Useful books and websites

“Ships are the nearest thing to dreams that hands have ever made.”

Robert N. Rose

Chapter 1

The Ghosts of Omaha Beach

It all started with a handshake: nothing fancier than that, no contracts with sub-clauses requiring signatures, witnesses and, heaven forbid, lawyers. It was just a brief clasping of hands. It was typically Swedish: brief and business-like, a couple of seconds at most, but it sealed a pact between us that would last more than eight years.

I often look back to that moment and wonder at the events that brought two committed landlubbers to a decision to sail around the world together, particularly as neither of us knew the first thing about sailing. In that respect, we bore little resemblance to our intrepid Viking forefathers. Add to that the fact that I was forty-something years old and had all my life suffered from such acute seasickness that the mere sight of a toy boat bobbing on a paddling pool would make my stomach lurch. So why on earth would I agree to a nautical global circumnavigation with a friend who knew even less about sailing than I did?

I grant you that the events leading to my handshake with Carl may have been fuelled by that feeling of bonhomie that steals over you after a good meal and a bottle of Bordeaux. An excess of wine may even have contributed to my agreeing to the scheme in the first place. And there was almost certainly the shadow of a hangover involved in the final decision-making process. But once Carl and I had shaken hands, that was it: the plunge into the unknown had been taken; the manly gauntlet to overcome my fear had been thrown down. The wheels were in motion and we were fully committed to the challenge of transforming our lives, leaving the security of well-paying jobs and the comfort of homes and families to risk everything.

The wine had been consumed at the top of a cliff overlooking the five-mile expanse of Omaha Beach in Normandy. It was here that the Allies arrived on 6 June 1944 to be thrown into one of the bloodiest battles of the Second World War. The conditions were against them from the start; the American landing craft had struggled against strong winds and rough waves, making it impossible for them to land at their planned sectors. Only two of the 29 support tanks made it to shore. Terrified young soldiers disembarked from the landing craft in deep water to discover unexpectedly strong defences. Those who didn’t drown under the weight of the equipment they shouldered and made it to the beach, were cut to pieces by machine-gun and mortar fire from the Germans who lay hidden in the cliff tops.

Carl and I were now sitting at the top of such a cliff, basking in the perfect weather and admiring the view: an azure sea sparkled below a cloudless blue sky, the broad sandy beach stretched invitingly below us. It looked innocent and pure as if it had never known that day’s unspeakable chaos and carnage. It was hard to believe that a drop of blood had ever sullied those brilliant golden sands.

Nevertheless, we both felt the ghosts of the past all around us; they’d been shadowing us on our cycle tour up to the bluff. As well as the museums, memorials and cemeteries, the Normandy coastline is dotted with poignant reminders of the fallen. Small plaques commemorate the number of soldiers who perished here, the distances between the plaques heartbreakingly short: eight hundred dead, three thousand dead, four thousand dead. The numbers are staggering; an estimated 425,000 Allied and German troops were killed, wounded or went missing during the Battle of Normandy. But it was only when we reached Omaha Beach itself that it really hit us: over a thousand American men had perished on the sands, most of them within the first hour of the landings.

We were sitting on the grass, quietly contemplating the scene below. We’d had a picnic of prawns and shared a bottle of red wine and were enjoying that pleasant mellow feeling you get after drinking in the sun. For a while Carl was lost in his thoughts and I in mine, but I’m certain we were both reflecting on life and death as we surveyed the landscape.

‘Did I ever tell you about my father’s old helmsman, Kurt Björkland? He took part in the D-Day landings,’ I eventually said, breaking the silence.

‘Really? And he lived to tell the tale?’

‘He doesn’t talk much about it, but apparently he enlisted in the British army and was one of the first to come ashore.’

Carl slowly shook his head. ‘He was unbelievably lucky. Think of all those poor lads who didn’t make it. Some of them weren’t even in their twenties, and now here we are, two blokes in our fifties.’

‘Speak for yourself,’ I said. ‘I’m only 43.’

Carl smiled briefly, then became serious again. ‘Makes you think, though.’

‘Certainly does. Kurt sailed around the world after that,’ I said. ‘Not just once but three times.’

‘Everyone ought to do something like that.’

‘Like what?’

‘You know, follow your heart, fulfil your dreams. At least once in a lifetime. Life’s way too short. We spend too much time dreaming about what we want to do and never doing it. It may be a platitude, but it doesn’t mean it’s any less true.’

I agreed with Carl. We continued talking about how life was all work and no play, that life was over so quickly we barely got the chance to dream at all. And again we were quiet for a while, sombrely contemplating this. Then Carl broke the silence.

‘I’ve got an idea, Yanne.’

‘Yeah?’

‘How about we sail around the world?’

I looked at him in astonishment. If he’d announced he was considering leaving his wife and three children to have a sex change and elope to Patagonia with the 30-year-old window cleaner, I would have been less appalled. My response, when I was finally able to regain the power of speech, was unequivocal.

‘Are you nuts, Calle? I throw up on the 20-minute ferry ride between Sweden and Denmark. There’s no way I’d survive puking my way around the world on a little matchstick boat.’

‘It was just an idea …,’ Carl protested, throwing up his hands in defence.

‘And a completely crap idea! Forget it!’

‘I only thought …,’

‘Well, don’t. And just in case it’s slipped your memory, let me remind you that neither of us knows anything about sailing. I don’t even like bloody sailing! Why would I start liking it now?’

My indignation at the preposterousness of the idea once vented, I cooled down enough to slap a somewhat subdued Carl on the back to show him I’d forgiven his foolishness. Me? Sailing around the world? Or even sailing? Was the man completely out of his mind? Carl and I had known each other for years. He should have known better than to even mention it.

We loaded our bikes with the remnants of our picnic, hoisted our rucksacks on our backs, left the cliffs and cycled inland towards Saint-Lô. Here, too, the Second World War had left its mark; the town was heavily bombed in 1944 and the church still bore the battle scars of the machine-gun fire. Carl and I each took a room at a pension in town. There, we ate dinner, enjoyed another fine bottle of wine and discussed our plans for the remainder of our cycling trip. Carl wisely avoided any further reference to sailing.

But damn it all if he hadn’t planted the idea in my head. And the crafty old bastard probably knew it. That night I slept fitfully as Carl’s words swirled like a fog in my head, ‘Follow your heart, and fulfil your dreams.’ Or was it the ghostly whisper of a young soldier who’d died on the sands of Omaha Beach reminding me to live life instead of watching it slip by? ‘Life is short, make the most of the time you have.’ I thought of Kurt Björkland and how he’d given his life purpose after the war. Life was full of risks, so why not decide to take the ones that made it meaningful. We only get one shot; I was already half way through my three score and ten and what did I have to show for it? Two failed marriages and a nine-to-five job to pay my mortgage. Hardly magical memories to take with me to the pine box that awaited. If my life lacked adventure, I only had myself to blame. So what was I going to do about it?

Carl was already sitting in the hotel restaurant, studying the map and eating a croissant, when I joined him for breakfast the following morning. Coffee was on the table and I poured myself a cup.

‘That idea of yours,’ I said. Carl looked up. I took a fortifying gulp of black coffee. ‘Apart from the horrendous seasickness, it’s not a completely brainless idea. Insane, yes; impossible, no.’

Carl put down his croissant. ‘What’s this? Are you still hung-over? I knew we shouldn’t have hit the brandy last night.’

I grinned weakly. ‘You’re right. You should never make a decision with a hangover. Not that it would be the first time.’ I sipped my coffee. ‘But my father’s always nagged me about learning to sail. I guess it’s time to take a crack at it and show him I can do it.’

‘Yanne, are you sure about this?’

‘Kurt Björkland survived the Normandy landings and circumnavigated the world three times. He gave his life purpose; I need purpose in mine. What the hell, let’s learn to sail. I mean, how hard can it be?’ I hoped I sounded more confident than I felt.

Carl’s grin was huge. ‘You’re on,’ he said. And we shook hands over the table. That was the start of it: the beginning of a pact between two friends. ‘Right,’ he said decisively, rubbing his hands together as if keen to get started immediately, ‘I guess we’d better get a boat.’

‘And I’d better get some seasick tablets,’ I said.

Carl’s grin faded, he looked suddenly solemn. ‘There’s just one thing I’m a bit worried about,’ he said.

‘Just one thing?’ There was a whole encyclopaedia of things I was already nail-bitingly, buttock-clenchingly concerned about.

Carl’s face had turned the colour of uncooked pastry. ‘How the hell am I going to tell my wife?’

Chapter 2

Auf Wiedersehen Berlin

In general, we Swedish are slow to make decisions, but quick to implement them. It’s an endearing national trait together with our penchant for flat-pack furniture and middle-of-the-road pop music. Carl and I, however, have always been quick to agree; we’re inclined to go with our gut feelings, so the idea to circumnavigate the world swept over us with alarming speed and lack of control. As usual, we threw ourselves at the challenge: hearts first, brains last.

Carl and I go way back. We’re both from the county of Skåne (Scania to English speakers) at the very southern tip of Sweden. It’s an exceptionally flat landscape – think Norfolk flat if you’re British, or Nebraska flat with a coastline if you’re American – so we have endless open fields dotted with picturesque windmills, ancient castles and a surprising amount of golf courses given the length of our miserable winters.

I come from Helsingborg, a small town hugging the coast at the narrowest point between Sweden and Denmark. On most days the Danish city of Helsingør (Elsinore) is visible, and fine weather might tempt you to swim the Öresund strait, the two-mile stretch of water that separates Sweden from Denmark, to Kronborg castle made famous by Shakespeare as Hamlet’s bastion. Not that I’d recommend the swim: if the shock of the cold water doesn’t get you, a ferry, cruise boat or tanker bearing down the Öresund towards Norway will. This particular stretch of water is one of three Danish straits connecting the Baltic Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via the North Sea and is therefore one of the busiest waterways in the world.

Carl was born and bred further inland in the even smaller town of Eslöv, whose claim to fame is that it has Sweden’s tallest wooden house, built, I assume, so people can admire the flatness of Skåne. Exciting stuff goes on here in Sweden, you know.

I first met Carl, however, in 1978, in former East Berlin during the days of Check Point Charlie and the Stasi. Germany was a strange place back then, desperately trying to shake off the shadow cast by the Second World War, yet still in its grip. The Berlin Wall was in its fourteenth year, and over a hundred people had already died breaching the border between East and West Berlin. East Berlin was an uninviting, purely functional place with regimented rows of imposing Soviet built concrete housing blocks dominating the cityscape: prisons have more charm.

Life behind the Wall was weird to say the least, especially to the many foreign workers who found themselves working in East Berlin on construction sites, as I did, in the late 1970s. I’d just turned 20 and had accepted a three-week job as an electrician on the construction of a hotel and department store. It was a huge job, worth 675 billion Swedish krona (approximately £80 billion at that time), an unheard of amount. Carl was 28 and project leader for the electrical department for which I worked. Twelve years later I finally left Berlin, having married, divorced and remarried. So much for three weeks.

I suppose I was seduced as much by the lifestyle I could afford as by the women I married. Foreign workers were exempt from the rules imposed on the East Germans, and the black market rate for our Western currency meant we could live like kings. I found myself a millionaire for the first and, unfortunately, last time. A bottle of imported champagne in a night club, for example, cost the equivalent of a can of cola in Sweden. Unsurprisingly, we drank it like water.

Despite my affluence, I was living in one of 50 caravans housing other Swedish workers parked on the Ostbahnhof car park. This was bordered by three colossal tower blocks, so tall they obstructed the sun after midday. Our commune of caravans became the entertainment equivalent of a third TV channel for the tower block residents, particularly in June when we celebrated midsummer in typical Swedish style with parties for 200 of our countrymen. And despite what you may have read, we Swedes know how to party, especially at midsummer. We bought supplies from the Intershop, the shop reserved for diplomats and those with hard currency, and provided at least 10 bottles of beer and a bottle of vodka per guest. We served great platters of pickled herring and smoked salmon, using huge oil drums to bake potatoes. The eating and drinking culminated in dancing around the midsummer pole erected in the middle of the car park and festooned with whatever greenery we could get our hands on, while belting out Swedish folk songs at ear-piercing levels. Bemused Germans hung out of their windows and watched with what must have been a mixture of amusement and envy from their concrete towers. Life was really tough for them; the shops were empty, as anything and everything people needed or enjoyed in Communist GDR was sent to Moscow: food, clothing, the lot. Meanwhile, we foreigners were cavorting decadently in their midst, flinging about our ill-gotten capitalist gains.

Mix into this the secret police and you have a surreal world. Stasi agents lurked on every street corner, spying on our activities. They keenly observed everything from the construction work to the antics at the parties and listened in on all our phone calls. If some poor sod said something stupid, critical or jokey, he’d find himself confronted by a couple of imposing types in dark overcoats and hauled off to a windowless hole for hours of questioning. One of our jobs was to run cables from 600 hotel rooms to a single control area where these faceless men could sit and eavesdrop to their suspicious hearts’ content, scribbling frantically until they ran out of pages in their notebooks.

Both Carl and I were trailed by Stasi agents. It was rather like having a series of personal stalkers. I was followed by various dark-coated individuals at a discreet distance of 10 feet for only a year before they lost interest in me. Carl was observed more keenly because he travelled throughout the country to meet suppliers and was therefore followed most of the decade he spent in East Germany. The Stasi tried to nail him for something or other, but they didn’t have a hope in hell. Carl was squeaky clean; he didn’t attempt to smuggle anything in or out, not even banned magazines or books. Nevertheless, they made life awkward. After the Wall fell in 1989, Carl returned to the city and managed to find his file in the Stasi archives. It was nearly two feet thick: they’d observed and meticulously noted every tedious detail of his life: from where he ate and stayed to whom he met. Looking back, I feel slightly offended they didn’t find me more interesting.

The crew working on the job was an uneven mixture of professionals and clowns – the majority being the latter – so it was astonishing we survived the experience. We were digging blindly in the middle of Berlin among unexploded bombs and high-voltage lines with neither drawings nor plans to guide us, all the archives having been destroyed. Instead, we had to put our faith in an odd bloke from northern Sweden who had an uncanny sense for detecting high-voltage lines. He would walk in front of the excavators with a metal rod, calling out when it was safe to lower the bucket; fortunately for him, and us, he never made a mistake. The quaint concept of workers’ well-being and a department overseeing their health and safety was a thing of the future.

There were more than a few maniacs working on the sites and a lot of drinking on the job which made an already unstable situation even more volatile, in turn spawning a “so what?” attitude. This was partly the reason why Carl and I became friends – we were both horrified by this lack of professionalism. Young and newly trained as I was, I was still keen to learn and do the best job I could. Yes, you might call me a youthful idealist, but I was eager to climb the professional ladder. Carl was similarly focused; he was a meticulous project leader and a good boss who appreciated hard workers. Our respect for each other was mutual and we knew we could trust each other implicitly. We didn’t socialize together much at the time, as Carl was living in a flat with his young family, whereas I was enjoying a bachelor life in my caravan. At least until I got married. It was only as our work together came to a close that Carl and I became better acquainted. He’s a bear of a man with a hearty laugh, a voice like a Harley in full throttle and a lusty appetite. He became something of an older, gutsier brother to me. Overtly what you’d call a red-blooded man’s man, his boisterous charisma also drew the ladies: a bonus for me, as being married Carl had to decline the come hither looks of the Teutonic blondes, leaving the field open for my more clumsy advances. By the time we returned to Sweden a decade later, we’d become friends for life who would go to the ends of the earth for each other.

What neither of us knew at the time was that one day we would do just that.

Chapter 3

Not Over the Hill … Yet

In 1997, Carl had reached a point in his life when he was supposed to be having a crisis: middle age. He was approaching 50, but he couldn’t help wondering from what direction.

‘Damn it all, Yanne,’ he growled. ‘For men of my age it seems you have two options: look old or look ridiculous.’

‘Which look are you going for?’ I asked.

‘Neither. My wife won’t let me do the first and my daughters have forbidden me from doing the second.’

‘Well, I guess that means buying a snazzy sports car is out of the question.’

Carl shook his head ruefully, but grinned a moment later. ‘True, but I can still have a snazzy sports bike.’

Knowing Carl as well as I did, I had a fairly shrewd notion that there was something about reaching a half century that was nagging at him: indeed, he’d confessed quietly to me of a growing yearning. I’d looked at him with alarm at this mention of yearning: many a middle-aged man has proved himself a bankrupt fool in an attempt to recapture his glory days with a young nubile beauty. My panic was allayed, however, when it became clear that Carl’s burning desire was not to swing naked from hotel bedroom chandeliers with a buxom blonde, but to go for a bike ride.

Not that this was just any bike ride, you understand. Carl had always enjoyed the freedom afforded by a cycle tour and was planning more than a quick pedal down to the beach and back. Over the winter months, he’d tucked himself away in his study and poured over the literature that fed his fantasy: maps and travel guides of Europe. He was due to work his last day as CEO for the electrical department of PEAB and had six weeks holiday before he began his new job. He would finally have the opportunity to relive something he’d done years before as a much younger man when he’d dusted off his old army bike, packed a camping tent, some clean underpants and a bottle of whisky and spent a blissful week exploring his home county of Skåne and its stunning coastline.

This time the plan was bigger and better; the fact that he was older and slower didn’t deter Carl at all. A week in Skåne was one thing, but he longed to go further afield. What I didn’t know was that he’d planned a cycle route of Europe, starting from Elsinore on the north coast of Denmark, continuing through England and France and finally into Portugal. Lisbon was his goal, and he’d given himself six weeks to complete the journey. Had I known earlier, I would most certainly have tried to talk him out of it.

But the first I heard about all this was at Carl’s fiftieth birthday party when he suddenly revealed his plans in a short, slightly slurred speech.

‘I’ve heard the call of the open road,’ he announced to the room. I rolled my eyes at the ceiling; what the hell was he thinking?

‘Don’t answer it,’ some joker quipped.

‘Bet you a bottle of whisky you won’t make it as far as the Helsingborg ferry,’ yelled another. There was raucous laughter from both the sober and the inebriated.

I got to my feet, swayed slightly and clapped Carl on the shoulder.

‘Calle, you mad fool. Have you really thought this through? Apart from the god awful weather, consider the wear and tear on your arse!’

He smiled ruefully. ‘You know how it is, Yanne. Once over the hill, you start to pick up speed. I want to make sure I set my own pace.’

‘Yeah, but to Lisbon and back,’ I may have slurred. ‘What’s so bloody marvellous about Lisbon?’

Carl shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I’ve just always felt there’s something … exotic about that city. Plus it’ll be spring there.’ He had a dreamy look in his eye that was almost pathetic, but damn it, if he wasn’t serious. This wasn’t some whim; he really needed to do this. Two gin and tonics later and the idea was rolling around my head that I should do it with him. He probably needed a co-pilot to help him navigate his way: or if not a co-pilot, then someone to ride shotgun in case of accidents or mishaps. At the very least he needed a sidekick. I decided that I should be that sidekick, and before I could stop my stupid, alcohol-muddled brain, I found myself addressing the room.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ I said in what people have since told me was a relatively commanding voice. ‘I hereby announce that I will be accompanying Carl on his cycle tour through Europe.’

‘Bloody fantastic!’ Carl roared. He frantically shook my hand and clinked my glass to seal my offer with a speed that suggested he doubted my resolve would last the evening, never mind the journey. Meanwhile, the rest of the room started a sweepstakes on how quickly we’d give up.

Why is it that one’s finest moments are never quite as fine on reflection the day after? I woke up at midday with that unsettling feeling you have when you know you’ve made a bit of a prat of yourself, but you can’t recall exactly how or why. I was fairly certain I hadn’t embarrassed myself on the dance floor, and I’d woken up alone, so more or less a good sign. But I couldn’t shake the sensation that I done something I was already regretting even though I couldn’t remember what it was.

When the events of the night finally filtered through my addled brain, my groan was loud and long. After a hearty brunch I began to feel better about it; after all, a cycle trip would be a way to get out of the working rut for a couple of weeks – that would be as much time as I could take off from the photo processing business my brother and I owned. I rang Carl to check our date of departure; no doubt I’d have a few weeks to prepare for the trip. For a start, I needed a bike, and maybe I should consider doing some light training.

‘I’m thrilled you’re coming with me, mate,’ Carl said when he answered the phone.

‘Wouldn’t miss it,’ I lied. ‘So when do we leave?’

‘The day after tomorrow.’

I laughed, such a joker that Carl. ‘No, really.’

‘Really, the day after tomorrow. Planning meeting at my house tonight. See you at eight.’ And he slammed down the phone, leaving me stunned for a good half minute before I started doing that panic running thing cartoon characters do when they fall off a cliff and plummet to the ground.

But my word is my bond, and my handshake is as good as a signature on a notarized document, so I headed to my nearest cycle shop.

‘And where are you cycling to?’ asked the shop assistant.

‘Lisbon,’ I answered without enthusiasm.

The assistant rubbed his hands with glee and directed me to the top-end racing bikes with more gears than Carl had celebrated birthdays and prices to match. ‘I’d suggest one of these. You’ll also need this saddle cover, a good pump – this one’s pricey but worth the money – a quality cycle bag and gloves. A helmet, of course. Oh, and I would recommend these cycle shorts and matching vest. Now what cycling footwear were you considering?’

‘Hold on,’ I said, steering the salesman back down the shop to the rack of cheaper city bikes. ‘One of these will do. And I’m not wearing all that daft clobber. A pair of jeans with boxers underneath will do me just fine.’

The cycle salesman snorted derisively, believing he’d spotted a cheap amateur if ever there was, which of course he had. ‘But you can’t cycle in jeans.’

I fixed him with a bloodshot eye. ‘When I was in the army, I cycled around southern Sweden and I didn’t have fancy spandex shorts then, so I don’t need them now. Furthermore, I’m not wearing anything that makes me look like an aerobics instructor.’

I chose a bike with seven gears and what I hoped would be a soft saddle. Right, so the equipment was sorted. But a small hitch in the plan was becoming horribly clear in the harsh light of day as I wobblingly peddled my new bike to my car. How in the hell was I going to cycle to Lisbon when I was barely fit enough to cycle to work? I pulled a muscle if I so much as sneezed.

Two days later, Carl stubbed out his last-ever cigarette, and we rolled our cycles onto the Helsingborg ferry to Denmark. Carl was as excited about his bike as a small boy getting his first two-wheeler. His company’s parting present was a red Cannondale, a proper racing bike with a ludicrous number of gears which I suspected he’d never use, but with which he seemed thrilled as he lovingly stroked the handlebars. You’re probably wondering why he didn’t opt instead for a mantel clock, but cycling is popular in southern Sweden: remember that Skåne’s a relatively flat county.

‘Ah,’ he said with a sigh of pure happiness. ‘Finally, six weeks holiday and my first chance in 30 years to really get out of the rut I’ve been stuck in. Right, let’s go. Lisbon here we come.’

The first day was utterly, numbingly miserable. The weather was shocking with snow storms and headwinds so strong we might as well have been pedalling backwards for all the progress we made. Neither of us was dressed for snow which pelted us in the face like well-aimed darts. We’d barely covered two miles in Denmark before I wanted to push Carl off his swanky bike and ride repeatedly over his prostrate body screaming, ‘Why the hell couldn’t you have taken up bloody marathon running like other middle-aged men!’ Instead I put my head down, glared at the asphalt and shouted at myself, ‘You bloody idiot! Nobody made you do this! You only have yourself to blame!’

Incidentally, anyone who would have you believe that Denmark is flat has either only seen it on a map, or is a deceitful, lying bastard. If you ever meet anyone who makes such a claim, disabuse them of that notion by whatever means you deem fit: preferably by insisting that they cycle the length and breadth of the damn country. They’ll soon agree that the Danish landscape is as hilly as a ski resort. Carl and I were forced to cycle 60 miles uphill standing in the saddle all the way from Elsinore to the town of Hundested in eastern Denmark. My legs burned, and my pounding heart confirmed my suspicion that I was a wretched candidate for our tour de France.

Eventually, our struggle through the bad weather was rewarded with a hot meal and a warm bed. We checked into an inn at Hundested; thank heaven, at least Carl recognized that our camping days were over and that some creature comforts were essential: good food and rooms with ensuite bathrooms. The following morning, revived by a full Danish breakfast of fresh rolls, rye bread, herring, cold meats and cheese, we began another day’s unhappy cycling with sleet lashing down in our faces like a storm of tiny knives.

I was beginning to regret not having bought the spandex cycling shorts. Furthermore, my “soft” cycle saddle felt increasingly like a small plank trying to wedge itself permanently between my buttocks – for the life of me, I cannot fathom how women manage to wear thongs. At the end of a day’s cycling, my thigh muscles were shaking with exhaustion. I fell from my bike and tottered shakily about like a toddler; it was like learning to walk all over again.

We had a brief respite from the saddle for 20 hours on the ferry between Esbjerg and Harwich on England’s east coast, allowing time for some sensation to return to my manly parts. We cycled into England and better weather; spring was bursting from every bush and tree, energizing us to pedal harder. Better still was the revitalizing power of the British beer which spurred us from pub to pub.

Then we arrived at Tilbury, a tired port on the north bank of the Thames where it seemed the sun dared not shine. I apologize to the good people of Tilbury – those of you who haven’t abandoned it – but if ever there was a bleaker, more miserable place in twenty-first century England, I hope not to see it. Once a smart ship building city, Tilbury has not aged well; the buildings looked neglected, the people dejected. Never have I seen so much litter; empty beer bottles, plastic bags and overturned shopping trolleys blighting the streets. Gangs of youths hung about, smoking and glaring malevolently at passers-by. We avoided eye contact and pedalled furiously through the town and down to the old harbour where we checked into a small hotel and hid. Early the following morning, we slunk onto the ferry and crossed the Thames. Gravesend, on the other side, was a complete contrast: the sun shone and the air smelled fresh; couples taking their quiet Sunday strolls smiled pleasantly and waved to us as we rolled by. With renewed vigour and hope in our hearts, we began the journey down to Portsmouth to get the ferry to the continent.

Cycling through southern England was idyllic; the weather improved, the wind was helpfully at our backs and we enjoyed the best that England’s fish and chip shops and pubs had to offer. We stayed in Portsmouth for two days to visit the naval base and Admiral Lord Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory. The oldest commissioned warship in the world, Victory was part of the fleet that twice defeated Napoleon Bonaparte’s, an impressive testimony to Britain’s naval achievements which even we seafaring Swedes could admire.

I should remind you here that the Swedish also have a proud history of shipbuilding, from Viking long boats to modern day racing yachts. Not that we’ve always been entirely successful with some of our vessels; we’ve had our fair share of disasters, one of which, the seventeenth-century warship Vasa, is an embarrassing example of massive ineptitude as well as proof that innovation is not always a good thing. In 1628, a splendid new warship commissioned by Gustav II, then King of Sweden, set sail on her maiden voyage out of Stockholm destined for the war with Poland. Vasa was a fearsome warship with a displacement of 1,210 tonnes and a hull built from more than a thousand oak trees. Her masts were over 160 feet high, carrying 10 sails with a total sail area a few feet shy of 1,400 square feet. She had 64 bronze cannon over two gun decks and could carry an army of 300 soldiers. Although designed as a fighting machine, she was a majestic craft decorated with hundreds of vividly painted baroque sculptures carved out of oak and pine, intended to reflect the power and the glory of the Swedish king. Vasa, so named after the ruling Vasa dynasty, required a crew of 150 men to sail her. She must have been an impressive sight, and excited Stockholmers lined the quay to witness her departure. As she proudly sailed out to the salute of cannon fire, men swarmed over her, hoisting sails and pulling ropes. The cheering crowds who’d gathered to see her must have thought this was the ship to beat all others.

Unfortunately, Vasa had barely sailed a single nautical mile before she promptly keeled over and sank. The crowds were still waving their kerchiefs when the ship heeled to port, and water rushed through the open gun ports, drowning at least thirty of the unfortunate crew. The ship’s lack of stability was to blame; the ballast was insufficient in relation to the rig and the cannon. Fingers were pointed, the captain was arrested and released, but nobody was ever officially blamed for the catastrophe.

Surprisingly, despite the brouhaha surrounding the sinking of an expensive ship on her maiden voyage – the ill-fated Titanic got further – Vasa was more or less forgotten for the next three centuries and left to rot in the waters of Stockholm harbour. Eventually, in 1956, serious attempts to relocate the ship were made, and she was finally raised in 1961 after 333 years lost in the mud. After years of restoration, she is now housed in a splendid museum in Stockholm and continues to impress. Fortunately, Swedish boat builders have since learned to ignore the hubris of kings and concentrate on building ships that float – a necessary component for seagoing vessels. Not that the British should feel too smug about HMS Victory: her maiden voyage was in 1778, so 160 years had passed since the mistakes of Vasa.

From Portsmouth we crossed to Cherbourg where the eight forts guarding the harbour entrance are evidence both of the strategic importance of the port and a determination to keep the English out. We were on historic ground, the scene of tremendous battles during World War II when the German forces all but razed the city to prevent the Allied forces from using it.

Ah, how we loved France: the wine, the cheeses and the cured meats. I find myself salivating just thinking about it. We cycled out of Cherbourg, did some 20 miles and entered the picturesque town of Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue where we headed directly to the harbour, confident of finding a local quayside bistro specialising in the catch of the day. We did indeed find a splendid fish restaurant where I swiftly cast aside my metal steed, threw myself at an empty table and clicked my fingers to the garçon to bring us a bottle of chilled white and a large shellfish platter. Then we sat back and watched the world go by.

What I love about France is that the country and the people remain so unrepentantly French, indeed flagrantly so: men with Gauloise cigarettes dangling languidly from pouty lips as they talk; women chatting at the speed of express trains as they pick over the produce at the local épicerie; shoulder shrugging en masse. Everyone seemed to have stepped out of a Jean-Paul Belmondo film. I was slightly disappointed not to see a man in a stripped T-shirt with a string of onions around his neck, but the waiter had a pleasingly Gérard Depardieu nose, a Gallic honker clearly evolved over centuries to be able to assess the bouquet of a Beaujolais nouveau with one deep sniff.

We were just assessing the merits of the second bottle of wine when four Brits, boisterous types in sailing jackets and waterproofs, plonked themselves down at the table next to ours. We didn’t think they looked like much initially, but appearances are deceptive; they turned out to be a doctor, a lawyer, a headhunter and a man who ran his own company, all of them so affable it was easy to fall into conversation. We eventually learned that they’d all learned to sail and once a year made a trip across the English Channel for a blokes’ week. They sailed, drank too much, talked bullshit and let loose the way men without their better halves generally do. They laughed when we told them we were doing much the same but on bikes.

‘You’re not serious,’ the doctor said. ‘You’re really doing this on pushbikes?’ We nodded.

‘Hell, if I had to travel on land, I’d have to travel by Bentley or Rolls,’ the lawyer joked. ‘Otherwise how would I pack everything I needed?’

‘Easy, you just pack this,’ I said, pulling out my credit card from my shorts’ pocket. Lubricated with wine, we all howled with laughter.

‘Can we have a look at your bikes?’ the doctor asked.

‘Sure,’ Carl replied. ‘I’ll show you my bike if you show me your boat.’

It was a quick tour, even though Carl insisted on demonstrating all his gears. The Brits chuckled over my extensive luggage – some underwear, a toothbrush and a warm pullover – then we strolled down to the harbour. As Carl and I stood on the pier gazing at the yacht, a feeling began to creep over me. I wasn’t sure what it was at first, but eventually I realized with dismay that it was envy: we were looking at a fabulous sailboat.

‘Think what we could do with a boat,’ Carl said in the awed voice of a man who has suddenly seen a heavenly light. Apparently, the feeling was catching.

‘Well, for a start you wouldn’t get blisters on your arse.’ I said. ‘But I’d rather have that than be seasick. That’s even worse.’

‘No, I’m serious. With a boat like this you could go for miles, using the wind instead of pedalling against it.’

‘Well, you have a point there,’ I conceded.

‘And it’s free.’

‘A boat like this doesn’t come free.’

‘No, the wind is free. And look how much room there is.’ Carl began to roar with excitement. ‘Say you had a bigger boat, you could live on it… Do you get what I’m saying, Yanne? Think of the possibilities.’

I thought of them. ‘Hypothermia. Drowning. Getting eaten by something with very sharp teeth,’ I said dryly. ‘Oh yes, the possibilities are endless.’

‘Yes, but you wouldn’t need anything else, no hotels or tents or eating at restaurants.’ Carl was almost jumping with excitement, his arms were going like windmill sails. ‘And you could see the world, Yanne. The whole world.’ And Carl’s eyes shone with that dreamy look again.

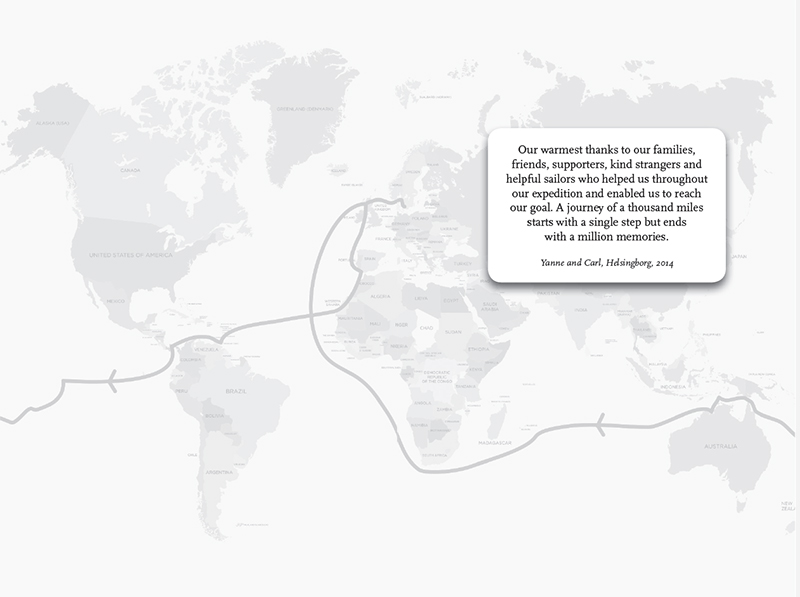

I blame those British yachtsmen; they put the idea in Carl’s head. The following afternoon, as we were sitting on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach, Carl popped the question and the next morning over breakfast in a small hotel in Saint-Lô, I found myself agreeing to sail around the world with him. We decided the date and exact time of departure there and then; we would set sail on 15 June 2002, at 15.00 hours, giving us five years to buy a boat and learn to sail it well enough to circumnavigate the world and hopefully not drown in the process.

A day later, I took the train back to Sweden; my two weeks were up and I had to get back to work at the photo shop. I was considerably fitter than at the start of the trip; my thighs now worked like well-oiled pistons, easily capable of cycling 80 miles a day, but I was beginning to develop a real cycle gait and walked as if I were on my bike even when it was chained to the nearest lamppost.

As for Carl, he never got to Lisbon. In order to escape a horrendous coastal storm, he had to change direction and head inland. He never reached his dream city by bike. Not that it mattered to him.

Why not, you ask, after all his meticulous planning and preparation?

Because he was planning a new route, a better route. As he merrily pedalled his way around France and back up to Sweden, the crafty devil was working out how to reach Lisbon by sea.

Chapter 4

So We Bought a Boat…

‘You did what?’ Carl’s voice boomed down the line. I held the receiver away from my ear. ‘You did what?’ he repeated.

‘I’ve bought our boat,’ I said lightly.

‘I thought that’s what you said,’ he boomed again. ‘What the hell, Yanne?’

‘Yeah, I know. But while you’ve been away, I’ve been doing some research and …’

‘Holy crap, Yanne. I’ve barely taken off my bicycle clips, got through the front door and kissed the wife and you tell me you’ve bought a boat! Couldn’t you have waited until I got back from France?’

‘Yes, but Calle, the demand for these boats is huge; they’re advertised one day and gone the next. If we really want to learn to sail, we’ve got to get a boat.’

‘Look, give me a couple of hours. I’ll come over to your place and we can discuss it.’ Carl didn’t so much hang up the phone as throw it across the room.

I looked around the kitchen in dismay; I doubted I’d have time to clear up before he arrived. Since my divorce I’d been living alone in my three-bedroom house. It wasn’t that I’d let the place go – in fact, I’m usually quite tidy – but while Carl was still cycling from vineyard to vineyard in France, I’d become gripped with a fever: sailing fever. Free of the responsibilities of married life, I’d been able to devote myself to searching for the perfect boat and how to sail around the world. The kitchen had become the centre of operations for our expedition, and I was in peril of being crushed by the piles of sailing literature that had gradually accumulated on every available surface. There were Swedish and English sailing magazines, together with stacks of textbooks entitled Sailing Techniques, Manoeuvres and Seamanship or Better Wind Management and, alarmingly, Emergency Care at an Accident Site: I was being very thorough. There were numerous adventure books: one on sailing in Antarctica, another about rowing across the Atlantic, not that we were going to do either but it didn’t matter; as long as there was a body of water in the title, I devoured everything and anything about crossing it. I was a man obsessed and it wasn’t pretty.

I hadn’t, in fact, bought a boat, but was very close to doing so having found something that suited our requirements near perfectly. With an unnatural amount of adrenaline coursing through my veins after making our solemn pact in France, I’d returned to Helsingborg and immediately set about searching for a 30-foot sailboat. With only five years to our sail date, we couldn’t afford to waste time training with a small dinghy. We’d agreed to invest around 200,000 krona (approximately £19,000 / $31,000) on a practice boat, as we called it. I knew Carl wouldn’t have time to hunt for boats, what with his new job, so I set myself the task. It was a labour of love and like most endeavours associated with that emotion, it was demanding, maddening and nearly drove me to tears and drink. No matter how many sailing magazines I leafed through or how many enquiries I’d made about boats I’d spotted on the internet, we still didn’t have our own. It was frustrating to read of other people’s sailing adventures when we, aspiring round-the-world sailors, were still two landlubbers without so much as a rubber dinghy. No sooner had I agreed to look at a prospective boat, than I got a call saying it had been sold to another buyer. I’d sulk and kick the sofa for a bit, then return to ploughing through the yachting magazines.

Carl arrived and I showed him into the kitchen. He looked round the room, lifted a bushy eyebrow and nodded thoughtfully.

‘You’ve got sails for brains,’ he said. ‘So tell me about this boat.’

‘It’s already gone,’ I sighed and explained to him how due to the popularity of 30-foot sailboats I’d already missed out on two.

‘I see,’ said Carl. ‘What about a berth? Have you looked into that yet?’

‘No,’ I said dumbly.

‘Just as well you haven’t bought a boat then,’ Carl snorted. ‘If you had, we wouldn’t have anywhere to put it. We’d better go down to the marina and sign up for a berth.’

Like many harbours, Helsingborg’s north harbour, can be very picturesque: sailboats sway gently on the sparkling water; a gentle breeze ruffles flags and makes wires clink softly against white masts; the sea beyond the harbour wall flashes golden in the sunlight. On a fine day, the towers of Hamlet’s Kronborg castle can be seen in Elsinore across the waters of the Öresund. Meanwhile on their side of the sound, the Danes have a view of Helsingborg’s imposing red brick city hall, our thirteenth-century watch tower, and the marina’s smart yacht club, a white two-storey structure built in the same architectural style as the newly finished residential buildings. Restaurants and bars bustle with tourists. It’s no wonder thousand-piece jigsaw puzzles feature summer harbour scenes. Ah yes, the idea of messing about in boats is very tempting in such a setting.

A different week in June and the picture is less appealing: boats rock alarmingly on dirty grey waves; wires and wet ropes whip mercilessly against metal; the churning sea throws turbulent waves over the protective harbour wall; the Danish coastline has disappeared under a thick veil of slanting rain and mist. Notice the lack of jigsaws featuring scenes like these; you’d get seasick just doing the edges.

It was on such a day that Carl and I had braved the elements, staggering from office to office to register for a berth. Standing in a puddle of water dripping from our jackets, it occurred to me that conditions might be worse at sea.

‘Crap weather, eh Calle? Do you think it gets much worse out there?’ I jerked my head towards the Öresund. Carl studied the floor – I think he was forming a carefully phrased lie when harbourmaster Peter Sandberg greeted us.

‘Hej! What can I do for you?’ he asked.

‘We’re planning to sail around the world,’ Carl replied with the slightly puffed-up attitude of a master seaman.

‘Really?’ The harbourmaster’s smile was sceptical. ‘I don’t believe anyone in the 100-year history of Helsingborg Yacht Club has ever done that.’

‘Well, we’re going to,’ I said, watching the sceptical smile grow broader. I glanced at Carl for backup.

‘We’re quite serious,’ Carl said solemnly. ‘We set sail on 15 June 2002, at 15:00 hours. So we need a berth.’

‘I see.’ The Harbourmaster smirked some more, then rifled in a cabinet for some forms. ‘So how big is your boat?’

‘Um, as of this moment we don’t have a boat.’

‘You don’t have a boat?’

‘Not as of this moment, no.’

‘And which moment do you think you’ll have a boat?’

‘We’re not quite sure. The fact is that we don’t know how to sail.’