The right of Juan Jose Millas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

© Juan Jose Millas 1999

© Santillana Ediciones Generales

Translation copyright © 2012 White Night Publishing

First published in English by White Night Publishing

c/o Thauoos and Co., 1st Floor, 201 High Street, Penge, London SE20 7PF

ISBN: 9781905603077

www.whitenightpublishing.com

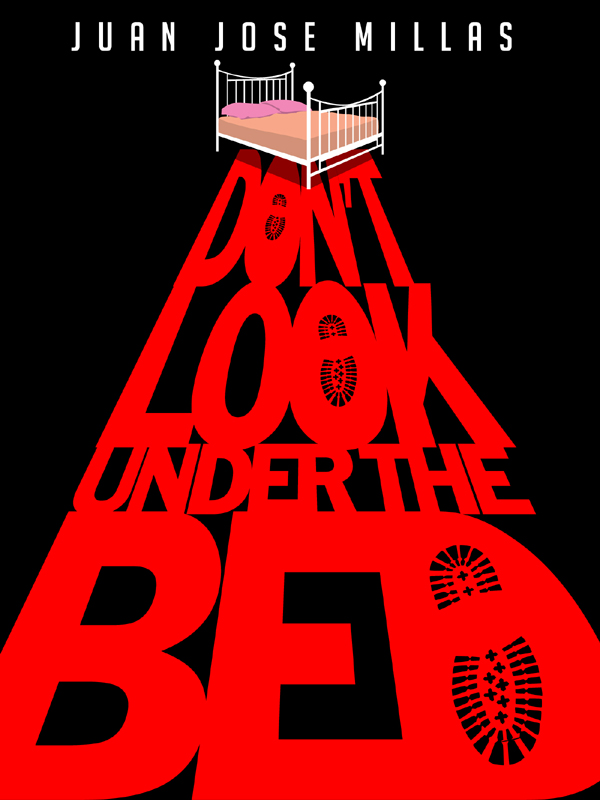

Front Cover Design: Bolt from the Blue

PART ONE

Judge Magistrate Elena Rincon and the forensic scientist attached to her department had just taken a corpse to Lopez De Hoyos and now were returning to the police court in the official car, driven by a very young man with an astonished look on his face. By his side, a thin secretary was nodding off over his black briefcase which he continued to clutch. If it was three o’clock in the morning in the streets, it was even more so in the spirit of the judge who, although she appeared to observe the empty pavements with an inexplicable interest, was actually carrying within her a corpse which had her own face and neck, her hands, her legs, her waist and didn’t show any signs of violence. If they had performed a forensic analysis, the report would have come out clean; nevertheless, the cause of the death had been a disappointment, a wound.

Months before, her father had died with the relief, if not the happiness, of seeing her turned into a judge with her own place in Madrid. Her father believed and had once made her believe that judges moved the world; perhaps they did move it in the small northern locality in which he had lived, and in which Elena herself had practiced during those first times after passing her exams, but not in a city like Madrid where the day to day grind in the courts was mind-numbing, and the shift work left an after-taste of bitterness which lay, like a lead precipitate, at the bottom of her spirit.

This time of night during her periods on shift always reminded her minute after minute of her father with a mixture of guilt and resentment. She had turned up at his burial with a certain haste and hadn’t even taken possession of the house after the funeral. She had limited herself to closing it up behind her as if it continued to be inhabited and returned to Madrid with the confused idea that as long as she didn’t move his things, he would continue to be alive, and she could postpone her pain, which in those instances she wasn’t feeling.

One night, she went as far as calling him on the telephone, and just at the moment that she realized her mistake, the answer phone switched on at the other end, and she heard the voice of the dead man asking that she leave a message after the tone. The judge hung up stunned, but she remained obsessed with the idea that she had found a way of communicating with the dead man, through which she could tell him everything that was upsetting her. That it was a lie that judges directed the world, for example, a lie that she had been given with the same care that he would have given her an ark constructed to save her from the deluge, but the deluge was life itself so that what had been created was a capsule in which I am isolated from existence, and for this reason I now don’t know the alleyways, nor can I conceive of the closed emotions that furnish the corners of my dark soul. Father.

This is what the judge was saying to herself in the depths of the automobile in which they were rushing back to the court house escorted by a police car with its sirens blaring, and her feelings about her father were so overwhelming that she was scared they had made her say something out loud, making her she turn towards this forensic scientist on her right.

“What’s up?” he asked, his look expressing nocturnal solidarity.

“Nothing,” said the judge. “I was just carrying my corpse.”

“If you need me to do an autopsy, come around to my office.”

Having said this, the forensic scientist with whom she’d already shared another shift, took out a cigarette and before lighting it, got rid of the tip, placing his nail at the exact point where it joined the cigarette. He never asked permission to smoke, and each time that the judge tried to censure him with a look of authority, he disarmed her with his expression of a child caught doing something wrong. In a way, he resembled Elena Rincon’s father.

It was his build, rather slight, and he could have passed for a qualified manual worker, possibly a good electrician or a perceptive plumber. He had very, very long fingers and despite not being young any more, his movements were agile. Elena Rincon and he had dealt with a number of corpses together, and the judge had seen him move around them with the ease of a technician capable of finding out the cause of the accident, of the death in body areas far removed from where the signs of damage to the tissues appeared.

They had already entered Castellana when the forensic scientist, seeing that the face of the judge was still clouded with grief, gave her two friendly, disturbing pats on her thigh. It was unusual for Elena Rincon to experience any erotic impulses during nights of shift work, particularly after transporting a corpse, and this added a further confusion to her state of mind. Having arrived at The Plaza de Castilla, the judge went rapidly to her rooms, letting herself fall on the bed of the room that was annexed to the office of the police court. Never, up to that night, had she set out things to herself things in a form so final, so brutal. Everything was a lie. And now what? She remembered a novel she had read in her student days about a priest without faith who officiated in his office with more dignity than he had before losing it. Could she honorably continue to carry out her work without believing in what she did?

Agitated by this cluster of feelings, she immediately left the room again and went into her office, dialing the number of her father’s house. She listened to the greeting message, the beep, and then, for a few interminable seconds, the silence of the house in which she imagined the furniture and the other objects sending out signals of strangeness, faced with this invasion from the outside world. She hung up without opening her mouth and stood there still, lost in her own thoughts, for a few seconds. There remained five hours of shift to endure, an eternity of unease, too much night ahead of her. So she left her office and went to see the forensic scientist who was expecting her, or so he said.

“I was expecting you.”

“So here I am.” answered Elena.

“Do you want me to do the autopsy now?”

“Of course.”

The forensic scientist explained that normally autopsies were performed in the institute in the morning at the end of shift. But he took her to an adjoining room where there was a couch and a white cupboard with all the equipment necessary to carry out small investigations related to accusations of assault, or rape.

“It’s not the perfect place for an autopsy,” he added, “but I can make up for the lack of equipment with my skill. Take off your jacket please.”

Elena took off her jacket uneasily, with the forensic scientist laying it down on the couch and examining it minutely, centimeter by centimeter, applying his finger tips to each irregularity of the cloth, to each fold, following the scars of the stitching which portrayed the emptiness where the body of the judge should be, her absence.

“You already know,” said the doctor, “that a good forensic scientist should perform an autopsy on the clothes even before the one on the body. The clues are to be found where they are least expected. Let’s have a look at the blouse.”

From that night, the judge magistrate and the forensic scientist established a relationship lacking any future; this was agreed at the instigation of Elena Rincon, and it did not matter to him since he maintained that the world had finished, and that they were only the residue of reality, its embers.

“In such circumstances,” he added with a caustic expression, “it wouldn’t have occurred to me to ask you to marry me even if I were a bachelor, which I’m not.”

They saw each other in hotels with which the forensic scientist must have been familiar from the way in which he entered and left them, and sometimes, but much less frequently, in the house of Elena Rincon who defended her private spaces with as much effort as he made to violate them. Desire, when it arose, grew precisely from the absence of a future, from the lack of any horizon. One day, finding themselves in the bed of a hotel whose rooms had mirrors on the ceiling, which appeared to the forensic scientist an admirable refinement, the judge looked at the reflection of her body and that of the doctor floating absurdly above their heads and thought they looked like two shoes belonging to different pairs. They had just had rather unrewarding sex in spite of the mirrors, since the forensic scientist had shown himself to be more able in carrying out autopsies than in sexual performance, and now they lay there on their backs, watching the column of smoke from the cigarette of the doctor, which rose up like mercury and seemed to penetrate that other world like a subtle thread which held the two together, united.

“We look like two shoes from different pairs.” said Elena Rincon.

“Then perhaps we ought to do it under the bed.” responded the forensic scientist. “Perhaps it isn’t working because we’re not doing it in the right place.”

The doctor proposed the move quite forcefully, but Elena Rincon demurred, suggesting that they should cover up the mirrors.

“Perhaps another day.” he concluded.

“Another day.”

The image of the two disparate shoes made the judge think of the curious nature of human beings, being by their own nature independent unities, yet desperately seeking a match that would complete them, as if each one were half of a conjunction. A lot of the miseries that afflict them, she knew from her daily work, belonged to this search for the match, or from the fear of losing it once encountered. She wondered if the shoes under the bed dreamed, in contrast, of each becoming independent of the other and becoming different individuals, autonomous. But, she didn’t say anything of this to the forensic scientist who, after putting out one cigarette and lighting another, stated that his wife and he fitted each other well, like two rather inflexible shoes perhaps, but of the same size, and identical quality.

“Nevertheless,” he added, “I like trying out shoe lasts that are different in kind to me which constitutes a normal perversion in situations of disaster. This obsessive idea of yours that being a judge doesn’t do any good bears a very close relationship to the using up of reality which, if you think about it, is already practically exhausted. When things really existed, then that was the most you could aspire to in life, to that and to being a doctor. Your father was right although he was a little out of date. Most probably he hadn’t understood about the end of the world. Nobody understands that.”

Elena Rincon attributed this apocalyptic vision of the forensic scientist to his need to justify his erotic insufficiencies.

Even if reality had expired, it was still strange that he didn’t give more of himself. In any case, although the results were so unsatisfactory, the judge felt that their encounters brought her closer to the life from which she had remained separated during her years of study. This development, together with her intuition that she was on the brink of something new, kept her in shape; if not happy, at least alive to what was going on around her, the conversations or gestures, changes of temperature or humor, coincidences or discrepancies. Her exam years had given her a noted capability for concentrating, and the aptitude she had acquired then she was now using on the streets, in the metro, in the courts, because she didn’t know where the signal would come from, nor at what time. On frequent occasions, she would phone her father to find out that in the family house everything remained the same and after listening for some seconds to the murmurings of the dark furniture, surprised by this unexpected invasion, she hung up again and returned to the world.

One day, taking the metro to the courts, she listened to the buzz of the passengers, whose behavior inside the carriages was like that of flies trapped in a glass box. She lifted her eyes from the floor and saw, seated in front of her, a woman whose features she had dreamed up for herself in some remote time. The woman was reading a book from which she only raised her eyes to lose herself for a moment, gazing into space before returning to its pages. She was an angel without wings, a goddess. Not without blushing, she imagined herself with her in the bed of a hotel whose rooms had mirrors in the ceiling, and it seemed that the two were forming a pair. The woman would be five or six years younger than she, around twenty eight the judge calculated, considering at the same time that in pairs of shoes there was always one a bit more worn than the other, depending on the walking habits of the wearer. She said all this to herself, joking a little in order to relieve the overwhelming impact produced by the stranger who was wearing her hair tied back in a ponytail, like Elena Rincon herself this morning. The heat had risen proportionately to the number of the travelers, trapped still in their winter clothes and looking needy, destitute. In contrast, the angelic reader wore a white blouse and a very short skirt, black, hardly anything. Everything was hardly anything about her. Her neck appeared to be a thread of silver with the rest of her corporal accidents dispersed around an intangible nucleus, contradicting the laws of gravity, so that rather than being seated she appeared to float above the seat. The judge tried to imagine a digestive event in the intestine of that subtle body and at once concluded that it was not possible.

The men, taking advantage of the way she was wrapped in thought, stared at the woman avidly, which Judge Rincon found hard to take. However, she did not appear to realize the havoc she was provoking in her vicinity. She had a particular look, perhaps a slight squint, which gave the whole face an expression of perplexity, of doubt. It appeared that she was asking something which nobody in that carriage, perhaps in the world, could ever answer.

Suddenly, time, which had decayed like an organic substance, gave place to a form of continuity that was not subject to duration, then recovered its hourly character, saturated with seconds, when the goddess got up and left the train in Gregorio Marañón with the agility of a hare.

This day, for Elena Rincon, was nothing more than a capsule in which she was traveling towards the following day with a disheartening lentitude. It was evening when she arrived exhausted at her house, that of a judge, since she had furnished it when she still believed that the magistracy was the true destination of existence, its driving force. In fact she was living in Fuencarral where Tribunal station was located, which now appeared to her an irony, and the rooms were laid with dark furniture and covered with enormous curtains whose folds evoked the feeling of an extinguished nobility. It also had a false chimney of wood, with doors, inside which a television was hidden which she hadn’t wished to remain in sight. One day, after having removed the corpse of a woman who had been left dead for a year in her living room in front of her television which was still on, she arrived at her judge’s house, turned on her own television, turned off the color and the volume and closed the doors of the chimney, abandoning the apparatus to its continual emission of sparks. In a certain way, it was a matter of creating a situation opposite to that suffered by that woman, and in its autopsy they would make out soap operas, game shows and remnants of advertisements that were undigested, in complete disorder. Always since then, when she crossed the drawing room of her apartments and looked at the ray of light flickering under the door of the chimney, she said to herself that inside there, in black and white, burned reality, or its embers, or perhaps the world, which, as the forensic scientist had affirmed, was at the moment of extinction.

Anyway, that night she shut herself up in her judge’s office that she had formed as one of the rooms of her house and tried to understand the metro-network according to the plan. She took it to Tribunal and from there she went straight to the Plaza de Castilla where the courts were. Perhaps the woman who read had also got on at Tribunal; there was no way of knowing. In any case, she got off at Gregorio Marañón. The judge hardly knew Madrid. She didn’t know what sort of street the metro of Gregorio Marañón opened out onto, but if the woman with the book had got off there; she thought it would have to be a grand avenue covered with the trees and statues and luxury hotels, occupied by people who were neither needy nor mean-minded.

Of course, she could have connected with Line 7 at Gregorio Marañón to go on to Guzman el Bueno, for example, or as far as the Avenida de Americ, where in turn there were new possibilities of re-embarkation, and so on endlessly. In that way, the plan appeared to her a network made for creating havoc. There was something diabolical in the possibility that one could cross with one’s matching pair in the tunnels and miss bumping into him by a few seconds, or through having taken the previous train, or perhaps the next. The judge was methodical. She always entered the first compartment at the same time and in the same invariable way. She couldn’t be sure that the woman who read was so orderly. Perhaps goddesses didn’t need to be like that. But she had to trust in this if she wished to preserve the hope of seeing her again. She imagined herself changing carriage every day, trying her luck five minutes before or five minutes afterwards, in order to try to provoke an encounter that perhaps would never happen and felt for herself an anticipated pity which pained her. Then, seeing herself bent over the plan of Madrid, calculating the infinite possibilities of going astray that the tunnels lent her, she feared she was beginning to go mad. She herself had conducted the preliminary investigations into more than one case whose protagonists were people of normal appearance who one night stayed awake on account of an obsessive idea, and as dawn approached, something toppled within them noiselessly and began to fall.

She phoned her father from her judge’s house, and when the answer phone turned on, she covered the phone with one hand and began to memorize the litany of the forensic scientist regarding the end of time. She knew the world for which she had been prepared had finished without doubt, but it was also true that since she saw the woman on the metro, the hour had arrived for her of the resurrection from the dead. Would the dead man have been capable of understanding all this? She thought not and put down the receiver, disheartened as she always used to be, after her first impulse to send him news about her life. Then she turned towards the living room, going back slowly through the rooms of her judge’s house and sat down on her judge’s sofa in front of her judge’s chimney in whose closed interior that night reality burnt just like a bush.

The next day the judge acted with the precision of an automaton in order to reproduce the facts of the previous day with such exactitude that their tying together would result as a logical consequence in the apparition, on the metro, of the woman who was reading. At her usual hour, she pretended she had woken up though she hadn’t slept and got dressed and went out to the street at the very same moment that she did every morning. And although she noted inside her head the presence of a mad cog which tended to accelerate her movements as if time was running faster for her, she managed to control herself and let herself be swallowed up by the mouth of the metro without any apparent difference from any other day, recognizing many of the usual faces at this hour.

Once on the platform and although she had the temptation to examine her immediate environment in case the angel herself were to appear, she disciplined herself by looking at the ground, perhaps also to put off disappointment, disillusionment. She saw a dead fish, the size of a pocket knife, which she charitably pushed onto the rails with the toe of her shoe whilst thinking that signs of the deluge were appearing everywhere, though in this case an inverted deluge. But once the doors of the first carriage pulled apart, she got on with her head high and crossed anxiously from one side to the other, making her way through the needy bodies. Suddenly, when she had started to flag, the goddess made herself manifest. She was standing this time, holding the rail with her left hand whilst in her right hand she held up the open book, continuing reading with the same level of abstraction that she had the day before. She hadn’t changed her clothes, but they gave the impression of being freshly worn. Elena Rincon placed herself as close to her as possible, making sure that this should not appear indiscreet and read over her shoulder, automatically, the title and a few lines of the book which was held open, while she smelt her skin and her neck and took note of the delicacy of her morphology.

Her proximity burned up her understanding, reduced to ashes anything that up to this moment could have held value for her. There was no ark in which she could place herself safe from shipwreck. When the train stopped in Gregorio Marañón, only two stations further on but almost an existence, an entire existence from the point of view of Elena the Suffering, the woman disappeared having glanced three times into space and leveled an enquiring gesture at the judge who survived it in some inexplicable way. Later examining the lesions produced by the separation, she stood appalled before the magnitude of the damage for she realized that she was broken in two, like a glove without its pair, inside a box.

In this fashion, dragging along what remained of herself like a crab cut through the middle, she got through the day and night with each and every one of its minutes that would not concede her the mercy of oblivion, of sleep, for a sole instant.