published by

Blotter Books

a division of

The Blotter Magazine, Inc.

ISBN 978-0-9839022-1-8

ISBN: 9781483552125

(liner notes)

Thanks to:

My husband Robin – of course.

Rev. Brendan Boone and St. John’s Metropolitan Community Church, of Raleigh, N.C. (www.stjohnsmcc.org. Come by and see us some Sunday.)

Margaret and David and all my other Gwyntarian friends, who welcomed me and helped me get in touch with my inner Silly Person.

Mouse and the Cave clan, all the way back to Meg.

Laine Cunningham, for editorially commenting in a way that didn’t make me wish to commit grievous bodily harm, to her or myself.

Michael Penny, for RINGSIDE, his greatest work of art.

Tim Funk, for his Salons.

Chris Roush of UNC’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication, for answering lots (and lots) of questions, and even smuggling me into a faculty meeting.

Jay and Pally, for dishing the dirt on how to run a club.

Tony Raver and Misty Dawn of Tiny Canvas Records, for telling me all about small independent record labels.

Mac Henry, for peerless legal advice.

WXDU – long may it radiate. (88.7 FM; www.wxdu.org.)

Cindy Jones, Tim Stambaugh and Mark Simonsen, for helping bring Mickey’s songs into the real world.

All the musicians who let me hang around, pester them with questions, sneak out the backstage door, quote lyrics, and generally go all fanboy on them.

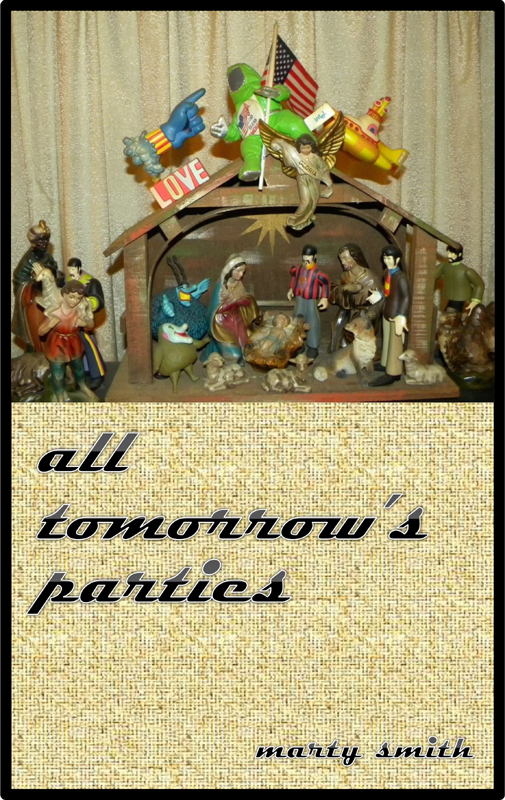

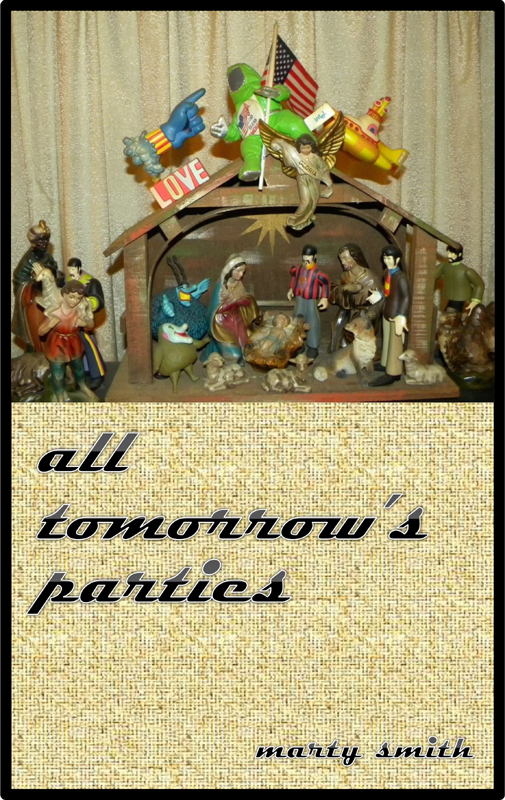

(Cover design: by author. Cover art: creche arrangement by Tim Funk; photo by Mark “Jewy Hendrix” Bennett. Author photo: Michael Choong.)

(This is a work of fiction. All the incidents in this book, and all of the characters save for a few tiny un-named cameos, are entirely figments of the author’s imagination.)

(All lyrics and excerpts quoted are with the permission of the authors and / or copyright holders. For documentation, e-mail m_k_smith@yahoo.com)

(Two portions of this work were published as “Hymnody” and “Party Girl” in the March 2012 issue of The Blotter Magazine.)

(tracks)

hymnody

merry christmas from the family

(back catalog) penny

(back catalog) chuck

load-in

set list

spread the word around

never break the chain

see my picture on the cover

hit the road jack

when the deal is done

your voice again

hey mister dj

joker smoker midnight toker

was a rollin’ stone

sunday mornin’ comin’ down

come hear uncle john’s band

against the wind

sister christian

cross the crowded ways

open mic

all together now

load-out

reprise

hymnody

This is my Maker’s world

And to my list’ning ears,

All Creation sings, and round me rings

The music of the Spheres…

-- “This Is My Father’s World,”

(Terra Patris, 6.6.8.6 SMD)

tune: Franklin L. Sheppard, 1852-1930

text (adapted): Maltbie D. Babcock, 1855-1901

****

“The night he played [the record] all the way through he felt his skin prickle at the back of the neck, the hairs rising all over his body and the white hot flush of communion with something sacred and all-powerful…”

-- Nick Kent, The Dark Stuff (2002)

merry christmas from the family

I’ll bring the smokes and I’ll bring the wine, and we’ll harbor up safe tonight;

Black cats and babies go to Heaven….

And everywhere you go you leave something beautiful behind

Everywhere you go you leave something beautiful behind….

-- Twilighter, “Black Cats and Babies” (2002)

* * * * * *

The same year the Beatles released Sergeant Pepper, a motel was built not far from Chapel Hill. It lay in a grove of pines near where Highway 70 passed under Interstate 85: two wings of ten rooms each, at right angles, with the office and manager’s quarters at the center. A gravel drive in front surrounded a lawn with a small swimming pool and a fire pit. A path behind the office led down to the banks of the Eno River. The motel stayed in business for several decades (longer than the Beatles were together, in fact), but despite the efforts of several successive owners it never made enough to pay back its mortgages, and finally closed. Until recently, though, people still lived there.

Its motel life was uneventful. No rock stars overdosed there; no desperate criminals were cornered in its nondescript rooms; no one saw God, the Devil or the ghost of Elvis in the neutral patterns of its carpeting. Long after it closed, however, things happened there which shook up the whole community: a fatal accident, a failed suicide, and murder. Certain things, once thought long-lost, were found.

* * * * * *

Andy always had a party in the dead week between Christmas and New Year’s: no longer one of his big ex-motel blowouts, but small and quiet, a hangout place for anybody stuck in town over the holidays. This night would see, at the most, three dozen guests. Some had come early, lingered a while, and moved on; others had promised to arrive late. Sally was splitting a second shift at the hospital and said she’d roll in about ten-thirty. Right now a small core were gathered comfortably in the former lobby, with its dusty bachelor-pad atmosphere of stale cigarettes, stale beer, air freshener and leftovers. At one end the old gas stove on the fake fieldstone hearth made a faint hollow roar, a yellow-orange glow flickering behind its front panel. There was beer in the fridge; and the big plastic bong with the “Just Say No” sticker on its chimney sat on the coffee table, next to an ashtray, matches, and a bag of pale green bud. MTV was showing retrospectives of dinosaur-old bands. “Dear God, is that Dee Snider?” Dorcas suddenly said, pointing at the TV. (It was indeed.)

She and John Overstead were on one sofa, he with his arm round her shoulder. They didn’t go out as much now that they were married – “we’re quite Domesticated,” John liked to explain, “complete with suburban ranch house and all” – but the first North Carolina party John attended, after moving down from Ohio, had been one of Andy’s “holiday betweens,” so he’d made a tradition of it. Rick Yost was on the opposite sofa with his current girlfriend Eviva Raikes. She was wearing “Ricky-the-Stole,” her favorite thrift-store find: an actual mink stole, over eighty years old, from long before the days of political correctness and animal rights, the head still attached and the mouth worked into a clasp so that it could drape, tail between teeth, elegantly over a lady’s shoulders. She was eagerly talking music with Brendan and Karl, rhythm guitarist and bassist of Calisteo, on tour and between shows – the Tabu last night, the Wherehouse in Winston-Salem tomorrow – and staying in Andy’s ex-motel rooms. (Andy had a standing offer of crash space to any band that played the Tabu.) Their drummer Nick was slouched down in another armchair near the warmth of the stove, his knit cap pulled low on his forehead, a wavery wasted smile below. His fingers had earlier been drumming out complex rhythms on the chair arm, but were now still. Billy Heffernan leaned against the counter, his palms down against its ledge, as though ready at any moment to push him into motion.

Andy as always was spread out in his preferred spot, his “throne,” a huge ultra-deluxe Barcalounger. It had sat in the exact same place longer than any of them could remember, ever since he’d brought it back in triumph from a yard sale in Caswell County. It had holders for cups (or beer cans) and pouches for remotes, cigarettes and magazines (or stash, rolling papers and lighter). Buttons in the right arm reclined the back and raised the footrest; or rather, would do so if he got around to fixing the motors. It was upholstered in deep maroon velour, now worn bare in spots and patched in others, and spotted with cigarette burns and bongwater spills.

Andy grinned up at Billy, indicating Nick’s inert form. “Remember how Chuck used to do that?”

Billy grinned back. “Yeah.”

“Who?” John inquired. “Or as the grammatical owl would say, ‘Whom?’”

“Chuck McDonough. Used to go to grad school here. One of Dr. Dave’s students. When was that?” Andy asked Billy, who shrugged. “Loved live music. Loved the Tabu. He’d come to my parties and pass out in that chair. But earlier he’d be singing Bugs Bunny songs and stuff!”

“We both did,” Billy smiled.”

John nodded. “A man of taste and discernment.”

Rick interrupted them. He’d been watching with some suspicion Eviva’s absorption with the band guys. “Andy, man, tell them how you got this place. You know he owns it.”

“Dad gave it to me!” Andy beamed and spread his arms, taking in the room. “His company fronted the money to build it. But they kept going bankrupt, because –“ he gestured again – “well, look; it’s too small. Twenty rooms? You can’t make a profit on twenty rooms.”

“Yeah you could,” Billy said. “Rent it as rehearsal space.”

“He already does, for free,” Rick replied. “You let me and Mickey Hill jam out here all the time. If he starts charging people’ll say fuck it. Did you call Mickey and tell him to come out? I hope he does. He needs to do some more Buckhorn Boogie shows.”

“So, like, you kind of inherited it?” Eviva asked Andy.

“Inherited? - Oh yeah. No. Damn! – lost my thought.” He tilted his beer and found it empty. “Hef, you wanna get me another Busch?” Billy sprang to his feet. Andy held the empty can up. “Anybody? Beer?” Nick stirred to half-life and raised a hand. Andy paused.

“Inheriting the motel,” Dorcas prompted.

“Yeah, yeah. They kept going bankrupt and the property’d kick back to Dad ‘cause he held the loan. The last owners skipped out on him; and about that time I was wanting to move out to the country, and I told him ‘Let me stay there and I’ll fix it up.’ Because they’d left it a wreck. Then after he died Ed and me each got half the estate, so I kept it.”

“That’s awesome,” Eviva said. “I wish somebody’d leave me a bar.”

John put the bong down and remarked, “I knew a girl in college who was set to inherit some money, and her stepdad tried to have her framed for murder so he’d get it instead.”

“Are you serious??” Eviva was appalled. “Did they stop him?”

John leaned back to reminisce in stoned comfort. “Trudy Horvath. She and I were both in architecture school at Kent. She was a couple of years behind me. Yes, they did catch him; this friend of hers, Penny Froward, who was visiting, figured it all out. She was determined to help Tru so she questioned everybody and talked to the police, and figured it out. Tru’s stepdad and step-uncle, I guess is the term, had lost a lot of money in a bad investment, South American oil stocks but the country had a revolution; money they’d snuck out of their jobs by sketchy accounting. Then her step-uncle shot her stepdad, and of course they caught him. He went away for a Long Time.”

“Was she a journalist or something?”

“No; She went back to Rockville and became a lawyer. Specializing in wills, in fact, last I heard. Rockville, Maryland. I always remember that because of the REM song. Don’t Go Back to Rockville.”

“If we’re nice to him he won’t sing it,” said Dorcas, matter-of-fact. “So the moral of the story is –“

“The moral is, when I’m stoned I become a Digressosaurus.”

“Who’re you gonna leave the place to?” Billy asked Andy.

Andy shrugged and lauged. “Damned if I know. You think I got shit to leave anybody?” He picked up the bong.

“It’s a good thing I don’t try to code while stoned,” John speculated.

“You got this place,” Billy insisted. “Who’ll you leave it to?”

“Everybody’s got something to leave,” Eviva said.

“My dad’s giving me his ’73 Charger,” said Karl.

“That thing is sweet,” Brendan added. “Fuck, man, he should give it to you now, not make you wait ‘til he’s dead.”

“I leave my kit,” Nick drawled.

“But all your porn, that’s going with you,” Brendan shot back. Nick raised his beer in silent agreement.

“The moral is, be careful what you ask for in peoples’ wills,” John concluded.

“You gotta make a will,” Billy persisted.

Rick cut in. “He’s right, you should. If you die and you don’t have one the government takes all your stuff.”

MTV had switched to a panel discussion on The Year In Music News. One notable item was the death of rap artist C-Mac, from hereditary heart problems amplified by years of hard partying. He’d been extremely and diversely successful, with two platinum albums, a Grammy nomination, clothing, shoe and jewelry lines, and a record label (Grievous Wrekkids). Through some grievous oversight on the part of his staff, however, he had died without a valid will. His ex-wife, girlfriend, manager and parents were now squaring off for a nasty fight over custody of his assets. “Case in point,” John remarked.

There was a clip from C-Mac’s breakout hit, “Kut Awff.” “Look at that,” Karl said. “He’s got so much bling on him he can’t hardly move. That’s what killed him.”

“That’s all his assets right there,” Brendan agreed.

“Ohh, and it’s got the same kind of women in it,” Eviva sighed, in exasperation and sorrow. “Every rap video always has the same kind. They’ve all got these huge –“ she gestured at her bosom – “like, everythings, and they’re always in thongs doing stripper dances.”

“It’s what guys want to see,” Rick said.

“Not because it’s sexist – I mean, like, yeah, it is, but – it’s, like, so unimaginative. They’ve been doing rap videos for years and years and years – can’t they think of something new?”

“When you’ve got that much bling you don’t have to think,” Brendan said.

“It was just one of those blings,” John sang in a light frivolous tenor. “Just one of those crazy blings; One of those bells that now and then rings…” Dorcas rolled her eyes, but was smiling.

The pull tab of Andy’s beer had broken off, so he’d dug out his Swiss army knife. As he searched through its various implements he said absently “I’ve been thinking about doing that.”

“What, dying intestate?” John asked.

“Dancing in a thong?” Dorcas suggested, causing John to stifle an explosive laugh.

“Who died on the Interstate?” Nick mumbled from the depths of his armchair.

“Start my own label, like he did.” Andy nodded at the TV. “Seriously, I’m thinking about it. I want to start one.”

“Who would be on it?” Eviva said, intrigued.

“You know for years I ran sound at the Tabu. We’d record the shows unless the bands specially asked us not to. And I’ve got a whole room full of those old tapes. Man, in fact –“ he turned to John – “if you can come out here some weekend and help me go through them, and see what I’ve got.”

“What kind of tapes?”

“Half-inch reel to reel.”

John looked troubled. “I wonder what condition they’re in. Magnetic tape doesn’t age well. Are they boxed up?”

“In boxes, lying flat. They’re in 14, next to the practice room. I’ve got a bunch of other stuff stored in there but it’s mostly old furniture. And I keep the blinds and curtains shut all the time, so it doesn’t get too hot. But I know I’ve got some amazing shows in there. Like from the Squirrel Nut Zippers when they were first starting, and same with The Old Ceremony. Two Dollar Pistols. All kinds of people. I bet I got about a dozen Sinnin’ Saints shows. And what I’d do is, I’d go to these bands and say ‘Hey, we’ve got these archival recordings of your Tabu shows, and our label wants to put them out on CD. We’d do like a 60 – 40 split in your favor.’”

“What if they said ‘Screw you, those are our masters, give them back?’” Brendan asked.

“Then we’d give them back. That’s how Ed always did it, from the start: we’d record the shows, and if they wanted the tape they got it. The last thing I want to do is screw anybody, especially bands. I just want to get these shows out there: they’re great and I want people to hear them. And I’d want as much of the money as I could to go straight to the bands.”

“If any,” John said. “With downloading, I don’t see how any label can make money.”

“We’d do downloads too. That’s something else you can help me with.”

“You’ve got them to leave too,” Billy said. “All your tapes. If they’re archival they’re probably worth money.”

“No shit,” said Rick. “I bet you got a gold mine in there. I’ll help you out too. Me and John’ll help you go through there, anytime.”

“I’m not gonna do it right away. I got construction jobs lined up for the next four months. Maybe we can launch it next fall sometime. I’ve still got a lot of legwork to do. Like the legal stuff, and backing. Maybe I can get Dr. Dave and Soundcheck to go partners.”

Headlights appeared at the top of the drive, and tires purred on gravel. Andy extricated himself from his Barca-throne, preparing to greet the new arrivals. Nick had begun quietly to snore. “There’s Dee Snider again,” Dorcas remarked, nodding at the TV, where Snider was chatting with the members of Blue Oyster Cult. “I wonder what’s in his will?”

“I want his hair extensions,” John said.

Dorcas turned to look at him. “And what,” she inquired, “would you do with them?”

John was stumped. “I don’t know,” he replied with a puzzled frown.

“Ugly son of a bitch, isn’t he?” Andy said. “But he doesn’t give a fuck. He’s happy. Ugly but happy son of a bitch. That’s the way to be.”

“Macrame!” John announced. Dorcas, Billy and Eviva all stared at him. “The hair extensions,” he explained. “That’s what I’d do with them.”

* * * * * *

There were lots of big parties there in the post-motel days. Some became annual events, with old friends driving back from as far away as Richmond or Johnson City or Myrtle Beach. A guest, wandering with drink in hand between the bonfire out front and the makeshift stages out back where local bands informally played, could meet someone they’d seen on the bus that morning, or in a class three years earlier, or from so long ago and far away that there’d be an uncertain memory-check moment before surmise could dawn into delighted recognition. “Man, is that you? It’s been ages! How the holy fuck are you?”

Fifteen years ago one such guest, drunk and stoned on one such night, had what he insisted was a really cool idea: every year the party should take a group photo of itself, all of them lined up together like on Sergeant Pepper; or like, one of those “A Day in the Life Of” books, with a bunch of pictures all taken at the same time but in different places. Because, he tried to explain, here we’ve got that same whole eclectic kind of group, from different eras and backgrounds and professions, and with all these different vectors of connectedness…Andy, equally buzzed that night, might have agreed if he’d been paying attention; but he’d been distracted by a serious problem, serious enough that at one point he and Mickey got into an argument that might’ve ended in punches if Sally hadn’t stepped in. Then the next day he learned that Chuck McDonough had had to leave town, nobody knew for how long, because his uncle had died. The photo idea was forgotten, and nothing ever came of it.

A Sergeant Pepper grouping; “A Day in the Life Of” book: what might it have shown?

(back catalog) penny

Gotta get down to it.

Soldiers are gunning us down.

Should have been done long ago.

What if you knew her and

Found her dead on the ground?

How can you run when you know?

-- Crosby Stills Nash & Young, “Ohio” (1970)

* * * * * *

Rockville, Maryland; early December. Christmas music has for weeks filled the artificial air of every mall and big-box store, jangling in the background of every other TV commercial. Penny Froward is resigned to it, though she says otherwise. By her standards, it’s uncouth to start Christmas-izing any time before the first Sunday of Advent.

The Christ Episcopal choir has begun rehearsals for its Christmas cantata. Harry picks her up after practice Wednesday night, returning with the boys from Chuck E. Cheese. A front-lawn nativity, its plastic figures of the Magi lit from within (their camel too is aglow), sets Taylor and Colin both singing. “We three kings of Orient are, Smoking on a rubber cigar, It was loaded and exploded, Now we’re on yonder star…”

Penny glowers at her husband. “I wonder who they learned that from.” His sheepish grin pleads guilty. She pouts. “I wanted to teach them that.”

* * * * * *

Now on this January morning, she readies her sons for school. Taylor, the younger, has recently found delight in Sunday-school songs, which he marches through the house rendering loudly, enthusiastically, and sometimes in tune. “WE ARE CLIMBING JACOB’S LADDER,” he bellows. “EVERY ROUND WE GO MORE HIGHER!!” Colin tries to mute the racket by placing a backpack over his brother’s head.

“You know, Colin, if you two were early Christians and got thrown to the lions, Taylor could sing at them and scare them off.”

“They’d eat him and then they’d barf and die.”

“I AM SINGING INSIDE A LION! EVERY ROUND HE GROWLS MORE HIGHER!!”

She can’t help but smile. She too at Taylor’s age was a loud and happy household singer. She’s more decorous these days, limiting her singing to the choir.

She looks at the clock. “All right, you two. Onward-Christian-Soldiers time.” She herds them towards the car. She’ll disperse them to their destinations, Colin to Beall Elementary and Taylor to the Christ Episcopal preschool, before going to her office. Taylor removes the bookbag and launches into “Onward Christian Soldiers.” Colin rolls his eyes and pretends to gag. The cat hides behind the laundry basket.

* * * * * *

She received her auburn hair and love of hymns from her mother, who sang soprano in the choir at Twinbrook Baptist. She always felt proud on Sunday mornings to see her mother come down the aisle with the other white-robed figures, singing the processional. Sometimes her mother even got to sing solos.

“Your dad courted me with hymns,” her mother once told her. Penny was five, sitting across the dining room table from her parents. “He stood under my balcony and sang them to me! ‘We Gather Together’ and ‘Kum Bay Yah.’ The tunes, at least. But different words.”

“What different words?” Penny wanted to know.

Her mother blushed. “Grownups’ words,” she said, and before Penny could demand more detail she continued “He had this ridiculous ukulele that he didn’t even know how to play. But that didn’t stop him. He kept strumming it: twang, twang, twang! Horribly out of tune.”

“I was in the spirit of playing,” Penny’s father said.

“Then Mrs. Arno’s dogs; she lived downstairs from me and she had these two Pekinese-es; they came to her patio door and started barking at him, barking and barking! I was on the balcony saying ‘Phil, stop! Go away, you’re making a scene! Phil, what have you been drinking?’”

“Communion wine,” her father replied.

Her father was a big man, with a rugged face and dark blond hair always cut short. In junior high her friends whispered to her how handsome he was. When she was older and with him in public places, she would notice women, and some men, stealing discreet looks at him. He had served in the Air Force and attained the rank of Lieutenant. He had a rich baritone voice. At church when they sang “God of Our Fathers, Whose Almighty Hand” (its page in the hymnbook made the exciting suggestion of “trumpets before each stanza”) she imagined him in full uniform, marching at the head of his squadron.

She was intrigued to note that all the hymn tunes had their own separate names, like semi-secret messages at the bottom of the page. “My Faith Looks Up to Thee” was “Olivet.” “Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise” was “St. Denio.” “God of Grace and God of Glory” was the exotic-sounding “Cwm Rhondda.” “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing” was “Nettleton:” a prickly name for a cheerful tune. “I Sing the Mighty Power of God” was “Forest Green,” sounding cool and pleasant and making her think of picnics. “Crown Him with Many Crowns” was “Diademata,” so she pictured a princess’s tiara sparkling with jewels. “Come, Thou Long-Expected Jesus” was “Hyfrydol,” with its comforting autumnal descent down the third stanza – “Israel’s strength and consolation” – like a gentle stream flowing through a forest of fall colors and into a still pool. “Morning Has Broken” (“Bunessan”) was a “trad. Gaelic melody; words: Eleanor Farjeon.” What was she like? Penny wondered. With a name like that she must have been interesting. The old hymnals were dark red, with embossed gold Gothic lettering, and a slightly nubbled texture pleasant to the touch. Inside they held a faint, churchy fragrance, musty and vanishingly sweet. “Is that frankincense?” she asked her father, beside her in the pew.

“It’s probably just the ink and paper.” He leaned over and murmured so her mother wouldn’t hear. “Incense is a little too sophisticated for your average Baptist.”

She loved the hymns, stately or reverent or calm or triumphant in their turn. They meant things to her that were too big for words. They marked important memories in her heart. “We Gather Together,” for instance, besides making her imagine Pilgrims and Indians waltzing in amity, meant Thanksgiving at her grandparents’ in north central Pennsylvania. It was the long car trip, ticking off each landmark as they went from freeway to highway to two-lane roads winding through the mountains until, her excitement rising, they came across the last ridge and saw the town below, curved round its river, lights coming on in the last of dusk. It was her and Mike, with Jason on his tubby little legs toddling furiously behind, tumbling up the wooden steps and through the fretwork door, into the warmth of wood-burning stoves and the Grandma Froward scents of potpourri and of apples baking.

“Morning Has Broken” was her riding with her father, headed down Rockville Pike. She didn’t remember when, or what errand they were on; the only important thing was that she had him all to herself. His window was open so his pipe smoke would drift out. The rich tang of his tobacco was a thrill to her. The radio was on, and suddenly played Cat Stevens’s version of “Morning Has Broken.”

“That’s a church song!” she exclaimed. “What’s it doing on there?”

Her father’s explanation was something kindly and wise, she was sure, along the lines of “Mr. Stevens liking the song enough to put it on a record.” She was astonished and delighted, as if some enterprising angel had escaped from church and set itself down in the real world.

Popular music never interested her as much. It was merely background, like the Muzak in Montgomery Mall. If a pop song did catch her attention it was because some quirk in its lyrics puzzled her. The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm,” for instance, caused her concern, with its dark red images in her mind of a killer stalking a family on holiday. “Was it about a real person?” she had asked. “Did they catch him before he could kill the people? Is he still in jail? Was this in California?” (in her imagining a strange and fabulous place, on the country’s farthest shore, where the people from TV and radio all lived). And what was Billie Jo McAllister throwing off the Tallahatchie Bridge? Who was Carly Simon singing to, with such venomous contempt, in “You’re So Vain?” What “Chain” was Stevie Nicks vowing would never be broken? When Janis Joplin sang of Bobby McGee, that near Salinas she’d “let him slip away”, what exactly did that mean? This too troubled her. When you’re as closely attached to someone as they seemed to be, you didn’t just “let them slip away”. Had they been separated in a crowd, and she not been able to find him again? Or had some darker force, seeking harm to the lovers – the Killer On The Road, perhaps? – taken him away?

“I Feel the Winds of God Today” was her mother’s solo at Mr. Horvath’s funeral. He had been their next-door neighbor and the father of Penny’s best friend; he had died of lung cancer. It was looking over at Mrs. Horvath and Trudy, both in black, clutching each other’s hand and trying to look brave; wishing so much she could comfort them; and later, her father giving up smoking. “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind” was all the times Mike argued with their father. Dad tried so hard to be patient and reasonable, but it only made Mike angrier. She remembered how even before she herself could talk, looking at the desperate fury on Mike’s face and the pain on her father’s, and thinking You don’t have to yell at each other! Just explain what you mean! They both needed the hymn’s “still small voice of calm” to speak through the earthquake, wind and fire. And “The Church’s One Foundation,” besides being the first hymn she ever saw that had feminine prefixes, was her parents telling her that courtship story, on a quiet night before tucking her into bed…As she grew older she came to learn that their early life had not been easy. Her father taught at Montgomery College and her mother was studying to be a pharmacist; there had not been much money. He was not religious, she was; and they argued over it, she feeling in those first years a quite serious obligation to “rescue” him. But by the time Penny grew old enough to observe them, their religious battles had settled into a gentle teasing; the secret language in which longtime lovers shared their affection. Her mother would look at her father and blush for no visible reason; he would reply by raising an eyebrow and wiggling his pipe with the side of his mouth. “The mystic sweet communion of those whose rest is won…” The hymn’s tune sounded like it ought to accompany a scene of angelic sunlight beaming down through clouds as at the end of an old Hollywood movie, the kind involving gruff, gentle priests and sullen boys redeemed from Hell’s Kitchen.

In junior high she went with Twinbrook’s youth group to retreats at a lodge high in the mountains beyond Winchester, where round the evening campfire she encountered old standards like “Shall We Gather at the River.” At Richard Montgomery High she joined the glee club but only lasted a semester, because their ambitious director had them attempt rock songs: a ghastly mis-use of choral ability, she felt. College was hard and law school harder. The passing music of the times remained mere background to her: on the radio, at parties, in soundtracks; sometimes referenced in test cases she studied on copyrights or plagiarism claims. She didn’t question pop songs any more, because she’d lost the habit of paying attention to them. Besides, radio rock by then had fragmented into so many separate styles, each with its own specialized target markets (none of which she felt she fit in), that trying to keep up wasn’t worth the trouble. Only at church did the old hymns remain loyally the same: reassuring, comforting, sustaining. “When Morning Gilds the Skies,” on a brilliant, cloudless, cool spring dawn. “Christ the Lord is Risen Today” on Easter Sunday. “Angels, From the Realms of Glory” at Christmas, with its tune name, “Regent Square,” like an elegant London address, and the stately summoning text of its third verse: “Sages, leave your contemplations; Brighter visions gleam afar…” On through her career, marriage and parenthood, they remained her touchstones.

* * * * * *

Penny was one of four partners in a law firm, with estate law her specialty. Their offices were in a sturdy 1910 mansion on Montgomery Avenue, whose parlors they had converted to reception and waiting rooms. Matt, the receptionist, was already at his desk: handsome like a classic movie star; always impeccably suited and groomed, and just as impeccably efficient. In the waiting room behind him, the beautiful walnut and marble fireplace had been retained and a gas log installed within; and on this bright but chilly morning its flames were a pleasant sight. A bookshelf held waiting-room magazines and (in dry lawyerly irony) a row of British murder mysteries: Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Agatha Christie, Penny’s favorite. She liked the plucky female characters Christie occasionally sent detecting: Anne Beddingfield in The Man in the Brown Suit, Lucy Eylesbarrow in 4:50 From Paddington. They’d lifted her spirits in junior high.

Penny’s own office was cozy and quiet, with its windows looking out to the side, away from the Avenue’s noise. A wooden fence smothered in ivy, framed by the trunk and branches of an oak, screened off the adjoining house. A tiny indoor fountain, which Harry had brought her from Japan, sat on its own little table in a back corner. Table and fountain were almost the same dark color as the wainscoting, making them near-invisible save for the glimmer of water.

Her e-mail inbox that morning surprised her with two messages from old friends, among the usual business communiques. The first was from Martha Klein, with whom she’d shared an apartment and several classes during her last year at Maryland and her first at Georgetown Law. Martha now taught at the University of North Carolina, and had written inviting her to a seminar to be held there the following fall. Penny followed a link to the website. “Inherit the Air: Intangible Assets in a Digital Age.” “Today, in what is being called the ‘Net Century,’ intangible assets and intellectual properties are increasingly located in ‘cyberspace’…” Topics: due diligence in determining the worth of software, databases and websites as assets….intellectual property and social media: protecting or reclaiming copyright on a piece that had “gone viral”….suggested asset-valuation methods for the likes of YouTube clips, Facebook followings, video-game concepts or the virtual items made and sold in Second Life….Creative Commons licenses versus standard contracts….what to do with a celebrity-endorsement agreement if the celebrity suddenly dropped dead. Four daily sessions, separated by 20-minute “Networking Breaks,” meaning a search for drinkable coffee and a hope the line at the womens’ room wasn’t too long. A Luncheon, with a Keynote Speaker, the judge who’d presided over Negativland / SST vs. Island Records.

Penny considered the idea with a faint nostalgic smile. It would be nice to have some girl time with Martha, whom she hadn’t seen in years. At Maryland one Halloween they’d attended a sing-along Sound of Music screening. There were people in lederhosen, peasant skirts, Alpine hats, schoolgirl dresses and ball gowns, a flock of brawny “nuns” with huge feet and five-o’clock shadow, and a slightly confused but happily sloshed fellow in a fur suit, old-fashioned diving helmet and silver bobble-antennae, who must have wandered in from a different party. Penny saved Martha’s note for further thought.

The second note was from Trudy Horvath, and chased Penny’s nostalgic smile into hiding. After the usual updates on children, husband and clients (she worked at a small architectural firm), Trudy wrote:

“Heres my BIG news. A crime documentary show called CITY CONFIDENTIAL wants to do an episode on Uncle Terry! They want to interview me and Robbie and Steve, and everybody else they can find. You too I bet since you did so much work on the case.” Penny winced, with a tiny growl of self-disgust. “They say itll air this time next year. Moms already said she wont work with them, she doesnt like remembering it. (She says Hi BTW.) But for me now its not embarrassing so much as sad. It was awful but we did live through it and survived and even got some of the money back. And you know one of the reasons I survived is because you were there helping me. Dont worry I didn’t sign anything! I told them to send me the legal papers so you can see them. Youll have to tell me what to say on camera so I don’t look stupid!”

I told them to send me the legal papers so you can see them. Youll have to tell me what to say on camera so I don’t look stupid!”

Penny and Tru had first bonded over the mutual horror of their names, agreeing that “Penelope” and “Gertrude” were burdens no person in her right mind should bear. They became staunch allies on the school bus and the playground and in the summertime parks. They went as regular guests to church with each others’ families, the Horvaths being Presbyterian. (Penny was surprised at first to see that Presbyterian “baptism” was just a sprinkling of water instead of Twinbrook’s full immersion, but by junior high she’d decided that it was a more dignified process than being dunked like a bushel of Third World laundry in front of all one’s snickering friends. Plus, they sang all the same hymns.) After Trudy’s father died during their 8th-grade year, Mrs. Horvath took the family back to Ohio, where her people were from. Penny and Tru kept in touch by letter and phone, always promising to visit.

Trudy had entered Kent State University’s architecture program. Penny, on her father’s advice, was deferring college a year and working for extra tuition money. When the dress shop that employed her announced it would close at September’s end, she decided to take the opportunity for that long-awaited trip. On an early October evening, fifteen years ago, she’d caught the Capitol Limited out of Rockville.

* * * * * *

That same night in North Carolina, a man at a party at an ex-motel suggested a Sergeant-Pepper-style group photo.

* * * * * *

The train was a nine-hour ride, arriving in Canton at two in the morning. She rode in coach and did not sleep well, troubled by train motion and the sudden roar of tunnels, and by dreams of Trudy forgetting childhood toys and friends as she drifted, or danced, off to some faraway campus. She awoke from them murmuring “no, no!” and with a sense of having to fight something off. At Canton she descended to a harshly-lit platform beside empty tracks and empty dark factories. Passengers weary in the dead of night moved through clouds of steam from beneath the coaches. Then a bright figure in a bright red ski coat rushed up and embraced her.

Trudy had grown. She was now Penny’s same height. Her face had shed its childhood roundness, and her voice settled an octave into assured adult tones. She still scurried around like a little gerbil, bright-eyed and breathless, her brownish-black hair in the same mess as always. She hugged Penny, exclaiming “It’s so good to see you, you look so good, was the trip ok?” while leading her down the steps and up into the station.

She put Penny’s bags into the back of a Pinto, and slipped with ease into the driver’s seat. Penny was oddly surprised, with the same unease that had troubled her dreams. Somehow she’d never visualized Trudy driving. She knew of course they both had their licenses; they’d talked about drivers’ ed on the phone many times when they turned fifteen. But the Tru she remembered had been fearful of machinery. She’d run away crying one long-ago summer evening, when her older brother Robbie had pushed a buzzing lawn mower in her direction.

They drove up through the empty downtown and merged onto a freeway. Tru chattered about her classes and the people she was meeting, and how in the fall she might move into a dorm. Then she grew quiet. There was sorrow on her face, dimly seen in the light from passing cars. “Mom’s not going to be there. She and Larry are divorcing, and she’s moved out.”

“Oh no.”

“They argued more and more all the time. I didn’t tell you.”

“You told me once they weren’t getting along. Oh, I’m so sorry….Should I go home and come back later, like next spring?”

“No, no, don’t! I’ve been looking forward so much to seeing you again. She wants to see you too. She said to tell you she’s sorry. Rob and I talk to her all the time but she’s staying away from Larry. No, please stay! I want you to meet everybody.”

“I’m so sorry,” Penny said again. She felt she ought to say more, or do more.

Tru didn’t know what they’d argued about, but suspected it was money. For instance, Larry didn’t want her to move into the dorms because of the housing fees: she could save all that money by living at home. Her mom knew she wanted to be closer to her classes and friends. She still wasn’t sure why her mother had married him at all. He’d been really helpful and nice to them when they’d moved back from Rockville; but it was more like being a good neighbor than anything else. How was Rockville, she asked; what had changed since they left? What had become of this classmate, that friend, those neighbors up the street?

Penny, tired, gave brief answers, You can tell me more tomorrow, Trudy said. There were mounds of plowed-up snow, crusts of sand and rock salt. Lit green signs looming above them, announcing Barberton, Alliance, Medina; Cleveland, Kent, Ravenna. Then the darkness of rural roads; then a sleeping town: courthouse on a square, red traffic light blinking at empty streets.

Tru lived in a huge Victorian house, chimneyed and turreted and gabled. Her bedroom had a round alcove formed by one turret, filled by a large draftsman’s table. Textbooks and clothes cluttered every surface. Her old quilt, beneath which they’d told each other ghost stories, had faded and frayed away to almost nothing. Her family of stuffed animals, for whom they’d once plotted all sorts of grand adventures, had retired to the top of the bookcase.

The household consisted of – or had consisted of – Trudy, her mother and stepfather, brother Rob, and her stepfather’s nephew Steve, sixteen. Tru’s mother and Mr. Garfield had taken him in during his own parents’ angry divorce two years earlier. He was tall, gangly, dark blond, and uncommunicative to the point of muteness. After the divorce his father, Mr. Garfield’s brother Terry, had moved to an apartment in Kent. (He kept promising that once he’d “gotten things straightened out,” Steve could rejoin him. In dubious compensation he’d given Steve a secondhand muscle car, with fat rear tires tilting it forward as though about to burrow into the earth.) Now Tru’s mother was gone. Rob was away in the Coast Guard, stationed at Sandusky. Steve stayed in his room or roared off in his car with friends. Mr. Garfield (thinning hair, a sharp face that looked unlikely to smile, and a precise manner, always straightening things) was the county building inspector, and often brought work home from his office. When not working he watched the news constantly or buried himself in the papers’ financial sections. The house felt haunted by absences. Steam radiators keened quietly to themselves in the darkened rooms.

The next morning, a Sunday, they slept late, then drove over to Kent. They went first to the dorm of Tru’s boyfriend Paul Frisina. They parked, and Tru hurried round the side to knock at a ground-floor window. When a face looked out she waved and called “We’re here, we’re here!” In a few minutes Paul opened the end door to them. He was Italian-looking, with black hair and stubble and just a touch of swarthiness. He was friendly and eager and grinned easily. He too seemed to have slept late, for he was barefoot in sweatpants and a t-shirt, with a faint gamy athletic smell about him. He noticed it himself, saying “I better take a shower.”

“Well, hurry up, we’re hungry,” Tru teased. Can we watch? Penny thought to herself, wondering if Tru had had the same idea.

(Penny at the time had not dated anyone seriously. She had never slept with anyone at all. She was willing, certainly; but it would be such a major step, both delicate and life-changing. It would have to be with someone she could really entrust herself to. None of the boys she’d known had seemed – she couldn’t find the exact word, but something like stable / responsible / mature / at ease – enough. She wondered intently if Tru and Paul were doing it. She couldn’t possibly ask. In childhood she and Tru had shared every confidence. Now after years of separation, there were certain topics she could not bring herself to talk of, as if she truly didn’t want to know.)

They planned a late breakfast at a pancake house, followed by a campus tour. They took Paul’s car, since Tru’s Pinto was too small for three people. Paul apologized to Penny as he hastily cleared the back seat of Coke cans, Burger Chef wrappers, crumpled pages of the Daily Kent Stater and a last semester’s textbook. He had a shoebox of cassettes, mostly Bruce Springsteen, in the space between the front seats. Another was in the player, blaring to life in mid-song when he started the engine. “You must be a fan,” Penny remarked.

“He’s amazing. He gets so much stuff in his songs, you could take a single one and write a whole movie out of it.” He sang along, drumming a hand on the steering wheel. “…story of the Promised Land, how he crossed the desert sands, and could not enter the chosen land…” Trudy joined him. “To face the price you pay…”

Penny could have done without Springsteen at that hour of the morning. She was not an admirer. His singing made her think of a tomcat yowling on a back fence. “Born to Run” was a melodramatic three-ring circus. She kept her opinions to herself, though, since it was clear she’d be in the minority.

In Maryland the leaves were just turning, but here they had already fallen, and lay frozen in drifts of the winter’s first snow. Kent’s population of black squirrels quirked and scampered on the white expanses like animate punctuation marks, or from high perches scolded down with an irate wheezing noise. The front of campus, facing the town, was a crescent of neoclassical buildings curved round the brow of a hill, centered on the Greek-temple-ish Administration, whose pediment housed an electronic carillion that sounded the hours. The rest was a sprawl of bland 1950s, 60s and 70s architecture, with a few modestly streamlined 1940s buildings mixed in, set among a typical campus maze of roads dead-ending into parking lots and paved walkways wandering in all directions. Tru and Paul ran a lively commentary on the architectural merits of the various buildings and pointed out other notable spots, such as the Taco Bell on Main Street whose bell kept getting stolen by frat pledges. (Paul, a Sigma Nu, swore innocence and blamed the Tri-Delts.)

They got out in a parking lot beside a featureless brick dorm. “This is where the people got shot,” Tru said.

Penny didn’t know what she meant, until tag ends of vague memories came up: a battle or riot at a protest march back in the Vietnam era; a photo in a LIFE Magazine anthology of a girl wailing in grief and horror over a figure lying motionless on the ground. Tru told her the full story. In the spring of 1970, after several days of violent antiwar protests (“they torched the ROTC building,” Paul added), a troop of National Guardsmen called in by the governor had fired on a crowd, wounding a dozen and killing four. The soldiers had knelt there, on the wooded hillside. The students fell here, where she and Penny now stood.

“The saddest thing,” Tru said – her voice gone quiet and sorrow rising to her eyes – “was, there was this girl Sandra Schueur; she lived in this dorm, she was a home ec. major. She was walking to class and got shot! That makes me so sad! She wasn’t protesting; she wasn’t even doing anything…”

There was a memorial, of sorts, built after years of angry argument and rejected proposals. A marker on a low small plinth marked the entry to a walkway, cut waist-high through a hillside and lined with polished granite. The hill was planted with daffodil bulbs, supposedly one for every soldier who had fallen in Vietnam. It was so discreet that it was nearly meaningless. Only a reading of the plaque would reveal that it even was a memorial.

Their last stop was Taylor Hall, housing the architecture school. It sat atop a hill overlooking the memorial. The top floor was an open studio with floor-to-ceiling glass walls, giving a view all across campus and town. White-topped drafting tables clustered in random groups like ice floes in a river, with here and there a partition haphazardly made of brown cardboard; and an armchair or sofa, tattered and unsanitary-looking as though they’d been rescued from beside a dumpster. There was a faint reek of ammonia, which Tru explained came from the blueprinting machine. On Sunday the space was deserted, with only one or two figures in distant corners bent over their drawings. Penny asked which desk was Tru’s, but was told that this was the territory of the fourth and fifth-year students; freshmen like herself and Paul worked on their projects at home. She and Paul did have work to do for Monday’s classes, so they dropped Paul off at his dorm and returned to Ravenna.

so