Copyright © 2013 by Tim Kelly

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

A division of ComteQ Communications, LLC

www.ComteQpublishing.com

Printed in the United States

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-1-935232-75-9

ISBN: 9781935232766

ComteQ Publishing

101 N. Washington Ave. • Suite 1B

Margate, New Jersey 08402

609-487-9000 • Fax 609-487-9099

Email: publisher@ComteQpublishing.com

Book & cover design by Rob Huberman

This book is written in honor of my wife, Gloria. She made it possible for my success in the world of basketball.

Red Klotz, September, 2013

For James J. Skedzielewski, who taught me much about basketball, life, honesty, and integrity.

Tim Kelly, September, 2013

Table of Contents

| Foreword by Joe Posnanski | |

| Introduction | |

| 1. | Pardon Me Shah |

| 2. | Philly Ball |

| 3. | Southern Comfort Zone |

| 4. | Little Big Man on Campus |

| 5. | A Changing World |

| 6. | Paid to Play |

| 7. | Sacrifice and Survival |

| 8. | It’s a Living |

| 9. | Pro Basketball Grows Up |

| 10. | Number One…With a New Bullet |

| 11. | The Duke of Cumberland |

| 12. | Abe Saperstein Calling |

| 13. | Evita and the Ambassadors |

| 14. | Berlin, Ballparks…and a Proposition |

| 15. | The Generals are Born |

| 16. | Generals and a President |

| 17. | Buzzing in the Hornet |

| 18. | Along Comes Wilt |

| 19. | Shrinking the Globe |

| 20. | The Amazing Abe |

| 21. | The Show Goes On |

| 22. | Re-evolution |

| 23. | Tennessee Lightning |

| 24. | Elder Statesman |

| 25. | Overtime |

| Acknowledgements | |

| Notes on Sources |

Foreword

As you will see in this wonderful book by Tim Kelly, it is impossible to sum up the amazing Red Klotz in a single story. But I like to think of this one: We were sitting in his office, and all of a sudden he said: “You know, I was almost on the cover of Sports Illustrated one time.”

To prove this, he pointed to a photograph on his wall – it was a mock-up of a Sports Illustrated cover. Red Klotz was on it.

“They never used this?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“No,” he said. “You know what they used instead?”

“What?”

“A beautiful woman in a bathing suit,” he said, and he smiled. Then Red looked out the window over the Atlantic Ocean like he had countless times before.

“What chance did I have,” he asked, “against a beautiful woman in a bathing suit?”

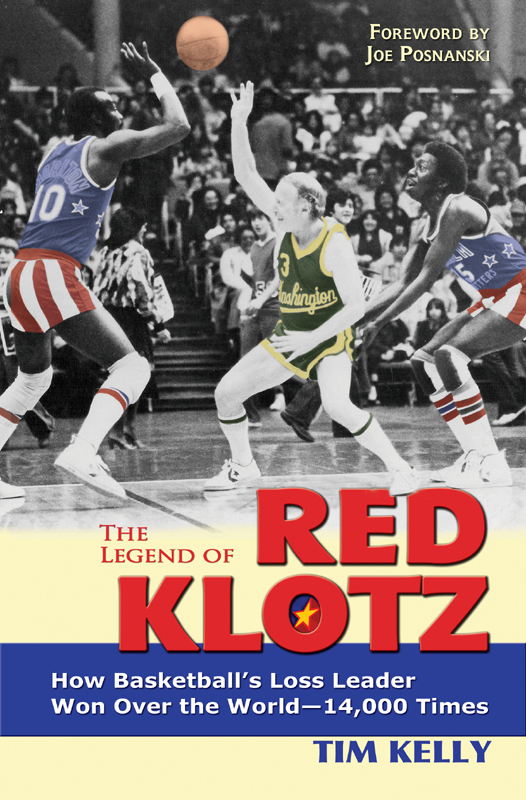

Isn’t that perfect? Red Klotz lost more basketball games than any man who ever lived. He lost games with the New Jersey Reds, with the New York Nationals, and with the Atlantic City Seagulls. He lost games with the Boston Shamrocks and Chicago Demons and Baltimore Rockets. He lost games with the International All-Stars and, most of all, with the ubiquitous Washington Generals.

He lost all these games to the Harlem Globetrotters, or, as he inevitably called them, “the world famous Harlem Globetrotters.” He lost basketball games in all sorts of places in all sorts of countries all over the world. He lost game inside and outside, on dirt and concrete, on sand and ice, on a battleship, and in a jail. He did not just lose games. He had his pants pulled down. He had buckets of water splashed on him. He fell for the hiding ball trick time and again. He chased after Globetrotters and chased after them and never caught them.

He also crossed that ocean outside his window too many times to count.

In the end, you find that winning and losing is what you make of it. There are countless so-called winners who cannot find happiness. Then there’s Red Klotz, still with Gloria 75 years after they met on a beach, surrounded by loving family and a million memories, living in that wonderful house in a little beach town by the Atlantic Ocean. He belongs in the Basketball Hall of Fame for all the joy he’s brought people and all the long jump shots he has swished around the world, but they haven’t voted him in yet. Sometimes people miss what’s right in front of them. Red Klotz lost games, but he won everything else.

“Look out there,” he said to me, and he pointed out toward the ocean.

“Yes, it’s beautiful,” I said.

“You know,” he told me, “every day it looks different. Every single day.”

“Because of the weather?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “Because of the ocean.”

Red Klotz at age 88 in his Margate, NJ office

Red, (top row, left) with his first organized basketball team, the Outlaws

Introduction

There can be little doubt the most traveled player/coach/team executive in the history of basketball is one Louis Herman “Red” Klotz. “I have run more miles on more courts, in more countries, than any other human being,” Red is fond of saying.

This is not some empty boast. As founder, owner, coach, tour manager, and star player, Red Klotz has played or coached, in a conservative estimate, in excess of 14,000 professional ball games in more than 100 countries during a career spanning parts of eight decades. The fact that the overwhelming majority of the games were on the losing end of exhibitions to the legendary Harlem Globetrotters hardly matters. Long before the National Basketball Association (NBA) was bragging about its globalization, Red Klotz was the most prolific foot soldier in actually laying the foundation. The NBA would not be comprised of 20 percent foreign players, nor would it have such strong international appeal, were it not for the groundbreaking work of the Globetrotters and Red’s team, the Washington Generals.

“The Globetrotters should get most of the credit for making basketball the second most popular team sport in the world,” Klotz maintains. “They couldn’t do it alone. We were there too, and we were part of it. We helped pioneer basketball all over the world.”

Red Klotz has played basketball in the Egyptian Desert, the Brazilian Rain Forest, and the Australian Outback. He has played on grass surfaces, dirt surfaces, and even the surface of an aircraft carrier’s flight deck. Red Klotz has played before popes, peasants, and kings, Christians, Jews, and Muslems, decorated war heroes, and maximum security prisoners. He played behind the Iron Curtain, the Bamboo Curtain, and the curtain of security guarding the classified locations of American troops. Along the way, he conducted hundreds of clinics on the game and left just as many basketballs behind.

“When we got to most of these places for the first time, everybody was kicking soccer balls around. When we returned, we’d see a few (basketball) goals. And now…well, now there are baskets hanging all over the place.”

Not only have international player taken over one-fifth of the NBA, so-called American professional “Dream Teams” have been beaten in the Olympics and international competitions by a diverse list of nations, including the former Soviet Union, its breakaway republics, and teams from Europe and South America. It’s not a coincidence that all of these places first witnessed professional games involving the Harlem Globetrotters and teams featuring Red Klotz as player, coach, and owner.

“Absolutely, Red Klotz belongs in the Hall of Fame,” says longtime friend Chris Hall, who won three NBA championship rings as a player and coach with the Boston Celtics. “People who think of him as the Globetrotters’ patsy just don’t get it. They don’t see the very significant impact he has had on the game. This is a gentleman who has opened the game to millions and millions of people.”

Of his 14,000-plus losses, former college and NBA Coach Don Casey said: “He should be in the Hall of Fame for that alone!”

Despite standing just 67 inches from the soles of his Converse All-Stars to the crown of his tangerine-colored locks that led to his nickname, Red Klotz thrived in a game dominated by giants. He won big at every level of the game before embarking on a career that took him to the losing side of the scoreboard versus the Globetrotters. His most recent win over the Trotters may have come more than 40 years ago on his last-second shot, but his winning passion for basketball and life transcends all. He is a stickler for fundamentals, and for doing the little things correctly. He is prideful of his role as a leading basketball ambassador to the world, and for launching the careers of hundreds of players and coaches.

“I owe him everything,” said the late Gene Hudgins, the first well-known black member of the Generals who went on to play for the Globetrotters. “He is an icon,” Hudgins told the Los Angeles Times. “He’s as important to the Globetrotters’ tradition as the Globetrotters…”

“Opportunities were scarce for black players in the 1950s,” Hudgins went on. “Red gave me the chance to play beyond college and to see the world doing something that I loved to do. He was like a father to me.”

Despite such heartfelt accolades, Klotz’ devotion to the game always has been overshadowed by his popular image as one of the most famous symbols for losing. He frequently is mentioned in the same grouping with Charlie Brown, perennial presidential candidate Harold Stassen, and the old Brooklyn Dodgers, who almost always came in second best to the cross-town New York Yankees. Pop culture references to Klotz’ history of losing have turned up on Monday Night Football, the pages of countless magazines and newspapers, and even on two separate episodes of the hit cartoon series, “The Simpsons.” “Ahh, the Luftwaffe,” Homer Simpson famously intoned, “the Washington Generals of the History Channel.”

But what is “losing?” Though the Trotters and Generals games are mostly about fun, Red has used his popular image to preach a serious message. “Losing’s part of life,” he said. “You can’t lose if you are striving to do your best. They keep score in a game to determine which team scores the most points. They call the team with the most points the winner and the team with fewer points the loser. But if you tried your best and didn’t score the most points you still won. Only one team wins the NBA championship. Only one team wins the Super Bowl. You mean to tell me every other team is not successful, just because they didn’t win the championship? It just doesn’t work that way. What matters is getting up. If you lose a game you can get up and try again the next time. That’s a win right there. You learn that lesson and you learn a lot about life. If you can regroup after a loss and keep going, you’re going to be OK.”

Never one to take himself too seriously, Red shifts easily from the philosophical back into his familiar comedy mode. In December 2011 following four consecutive losses, NBA superstar Kobe Bryant said that he wished his Los Angeles Lakers had the Generals on the schedule. Red, with tongue in cheek, graciously offered to play the game. “We haven’t beaten the Globetrotters in 42 years, so I know a little bit about what Kobe is going through,” he said.

Red wasn’t always a loser. He led his South Philadelphia High School teams to a pair of Public League titles and the city championship in 1939-40. The following year, he sparked the Villanova freshmen to a 32-0 record and starred on the winning varsity team in 1941-42. During World War II, he was a key member of the Army Transport team, along with future Philadelphia Warriors’ ace Petey Rosenberg. Red was a member of an American League champion Philadelphia Sphas, a dominant pre-NBA pro team, and he won an NBA championship in 1948-49 with the Baltimore Bullets. He is tied with six other players as the third-shortest player in NBA history, and he is still the shortest ever to win an NBA crown. Hardly a loser’s resume.

Klotz began playing against the Globetrotters regularly in 1950, and then with his own organization in 1952. He didn’t stop playing professionally for good until the age of 68, making him one of the oldest professional athletes in history. Even then, he still packed a uniform on the road in case of being needed in an emergency. “In fact, I’m still available!” he chirps. He played competitively in half-court pickup games into his 90s, and when he stopped doing that after a series of strokes, he continued to go out on the court and shoot. His famous two-hand set shot, once the game’s standard technique, is now a relic from when basketball was played in cages and hotel ballrooms. Red has kept the shot alive, with stunning accuracy.

During an informal conversation about basketball, the author offered that Pete Maravich was the best pure shooter he had ever seen. Following a pause, Klotz said “you mean the best onehanded shooter you ever saw.”

Cindy Loffel is a longtime friend and the only female in Red’s former group of pickup players. A former Division One college player, Loffel often was matched up against Red.

“He’s another player out there I’d be trying to beat,” she said, “and it was a real challenge to try to stop him. “He put so much into it every time he stepped on the court. It might be a fun pickup game, but he took it very seriously.”

“Sometimes,” Loffel said, “I really stop and think about what he has meant to the game of basketball. His contributions are truly remarkable.”

Maybe Loffel hit on an explaination as to the reason why Red’s Hall of Fame induction is still pending.

The man has one of the great under-appreciated legacies in basketball and until now, one of the last great untold stories in all of sports.

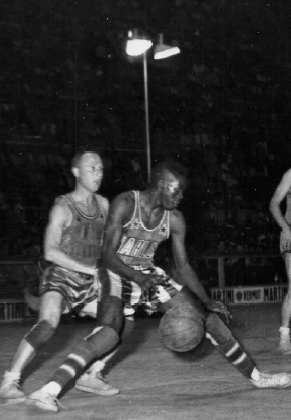

Red guards an unidentified Globetrotter during an early European tour game, 1951.

Chapter 1

Pardon Me, Shah

Where were the basketballs? The unsettling thought came to Red Klotz as he prepared to take the court with his Washington Generals and face the world-famous Harlem Globetrotters.

As owner, coach, and tour manager of the Generals, the Globetrotters’ primary opponents, Red had plenty to worry about. Player acquisitions and contracts, hotel arrangements, and transportation were just a few of the major items crowding Red’s plate. Locating the balls for pregame warm-ups? That was a detail left to one of his players. On this particular night, Friday July 22, 1955, whoever had been in charge of the task had let Klotz down. The canvass bag of orange leather spheres was nowhere to be found.

This wasn’t a routine game among the roughly 300 the Generals and Trotters would play in a typical year. It was the second of two scheduled at the request of the U.S. Department of State in the politically and religiously-charged city of Tehran, Iran. The night before, the teams squared off in front of an audience comprised mainly of peasants. In attendance on this night was none other than His Imperial Royal Majesty himself, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shahanshah or, “king of kings:” The Shah of Iran.

There were no basketball facilities in Iran, as was the case in most parts of the world in 1955. The Trotters and Generals carried their own equipment along for such occasions. Along with the traveling party went the world’s first custom-built portable basketball court – a seven-ton wooden floor – as well as heavy steel poles anchored by sandbags to support the backboards and goals. If they couldn’t bring Mohammad to the mountain, the Harlem Globetrotters could bring a basketball court to the Shah of Iran.

Just as they had done previously in the British Isles and throughout Western Europe, Africa, the Far East, and Australia, the ballplayers were introducing the American sport to a whole new audience. Not with intense competition, although that did occur, but through comedy, music, and what would come to be known as sports entertainment. This time, their appearance was the result of a request by their government. They had endured difficulties and had made their way to the Middle East. The newfound fans of the game were eating it up.

Red scanned his surroundings for the bag of basketballs and he couldn’t help but be impressed by the scene. For a guy who had faced the Globetrotters in bull rings, ancient Greek amphitheatres, and soccer fields, this was something altogether different.

At this relatively early stage of his career, Red Klotz had coached and played in well over 1,000 games on the way to his career total in excess of 14,000. He was accustomed to dealing with the unexpected, but this was a new one. “We were outdoors in a field surrounded by grandstands, and they were packed,” he remembered. “There was a low fence around the area. Low enough that hundreds of people could easily climb over it…and they did. The only boundary that meant anything was a line of armed Iranian military troops.”

Red looked on in astonishment as dozens of anxious spectators jumped the fence at one end of the field until the guards came over. No sooner had they controlled the area than dozens more would jump the fence at the other end. “This kept going on, with the guards running back and forth,” Klotz said. “They used long wooden sticks to lash at the crowd and move people back. They weren’t asking anyone to move. They were telling them with solid wood.”

At center court, something else caught Red’s eye. The Shah was looking on from a specially built royal viewing platform. The stands were divided, with the Shah’s perch in the middle. It contained Pahlavi, family members, and an additional compliment of armed guards. “The Shah was isolated and was not mingling among his people,” Red recalled. “He couldn’t be among the people, because of attempts that had been made on his life.”

Just a few years prior, Pahlavi’s regime had taken over British refining interests in the oil-rich kingdom and nationalized the industry. The royal family had accumulated spectacular wealth while millions suffered in poverty. The anti-Shah sentiment was growing steadily and would explode in 1979 when Pahlavi left the country for cancer treatment in the U.S. His government would be overthrown while fundamentalists seized the U.S. Embassy and took U.S. citizen hostages.

The Shah’s popularity had started to wane decades earlier. At a 1949 public ceremony in Tehran, an assailant somehow breeched security and fired five shots. One of the bullets grazed Pahlavi, and the would-be assassin was shot and killed on the spot by the guards.

Such history resulted in the show of force at the game, and despite the dangers, Pahlavi looked on in the very public setting to observe the American athletes. By his side was the second of his three wives, Malakey (Arabic for Queen) Soraya. More of the rifletoting military officers guarded the area in front of the box, so positioned to serve as human shields, if need be.

A plush, bright red carpet ran from the edge of the basketball court to the steps of the platform. “Better to hide any blood that might be spilled,” Red said, only half-kidding. “Things over there were a little jumpy.”

Nevertheless, Red was at an age when dangers and hassles just didn’t seem to matter. Why would they? Klotz was being well-paid to play a game he loved against a great team. Together, they were introducing basketball to millions of people.

The Generals were second fiddle to the Globetrotters and always would be, but Red’s team was selected from the best talent available in order to push the Trotters to play their best. Through the years, this would mean signing more than two dozen players talented enough to switch locker rooms and sign with the Trotters. Some, like Greg Kohls and Bill Campion, were big name players in the college ranks, and a select few, like Charlie Criss, Med Parks, Sam Pellom, and Ron Sobie, made it to the NBA. One, Nancy Lieberman, became the first woman pro to play with men, and would be enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Red’s efforts with the team would stretch over 14,000 games in 100 countries and more than six decades. However, on this night in 1955, Red’s and the Generals’ impact on the game was not at top of mind. The main objective was to get through the game successfully and without incident.

At the time of the State Department’s requested Middle East appearance, the Globetrotters’ brilliant entrepreneurial founder and owner-coach, Abe Saperstein, was on the verge of wrapping up his fifth triumphant international tour. Crowds were receptive and enthusiastic in places where Cold War propaganda had painted an ugly picture of America.

The all-black Trotters and integrated Generals dispelled many preconceived notions. Two teams shared the same court, laughs, and good sportsmanship in competition. The laughter and fellowship that was apparent deflated many ideas about racial prejudice and inequality. Some of the Communist nations were holding that African Americans had not advanced much at all since the abolition of slavery. It was true that race relations still needed to come a long way in the U.S., but one never would know that from what was happening on the court in Iran that night.

The tour’s appeal also could be traced to Saperstein’s intuitive sense of promotion and star power. The London-born, Chicagoraised Abe was the first person truly to understand and exploit the fact that professional sports were entertainment. In contrast, the NBA, spawned a decade earlier by large arena owners, had not yet gotten the hint. The NBA had plenty of basketball talent, but the games were slow and plodding, especially next to the freewheeling style and speed of play displayed by the Trotters and Generals. In an effort to boost attendance, Abe’s team also was hired to play in doubleheaders with the NBA squads,

In an interview for a Globetrotters’ documentary, Boston Celtics’ Hall of Famer Bob Cousy talked about the folly of having the Globies open such twin bills. The owners would sell a lot of tickets, and when the Trotters-Generals’ “preliminary game” was through, “half the house would get up and leave,” Cousy said. That only happened a few times before the owners wised up and switched the NBA games to the preliminary billing.

At least 30 years before “Showtime” was coined to describe the 1980s’ Los Angeles Lakers, Saperstein was dimming the house lights and having his players burst through a giant paper basketball-shaped Globetrotters logo and run onto the court to the strains of “Sweet Georgia Brown.” Brother Bones’ toe-tapping version of the song was blared over the public address system while the crowd clapped along and the Trotters formed their “magic circle” at midcourt. They performed all kinds of ball tricks and fancy dribbling, spun the balls on their fingers, and rolled them across their backs and down their arms.

Once the game began, the Trotters’ usual method was to roll up a big lead and then perform comedy routines, or “reams,” during the action. They always had a dribbling specialist and a dead-eye shooter who could convert long hook shots from a distance seldom seen in conventional competition. As if that weren’t enough, Abe kept things interesting at halftime and pregame by adding jugglers, acrobats, table tennis champions, singers and dancers, and star athletes from other sports. The Globies weren’t just a basketball team. They were a traveling variety show.

The fans responded at the turnstiles, and the Trotters became international sensations. The Generals’ talents also were recognized with appreciative applause both at home in the U.S. and on the world stage. The little five-foot-seven flame-haired guard from South Philly proved to be a big crowd favorite. Red Klotz had the uncanny ability to nail his two-handed set shot and his nearly-as-deadly hook from long distances. Klotz also participated in many of the reams. His specialty was to chase the Globetrottters’ dribbler in a well-choreographed routine, or he would improvise something on the spot. In between the tricks and comedy, the teams slugged it out in serious hard-nosed basketball played at the highest skill level. It was a winning formula.

“We made people like Americans wherever we went,” Klotz said. “Language barriers and social customs did not matter in the slightest. We went into places that hated America, and by the time we left, they were bowing down to us. That’s no exaggeration. Laughter has no language.”

Said ex-Trotter and NBA star Connie Hawkins: “We were…the Pied Piper. Everywhere we went, people would be walking around, following us.”

Basketball-wise, the product Saperstein rolled out was jaw-dropping. Though known as a flamboyant showman and promoter, Abe was a basketball guy first, and the Trotters certainly could play. By 1955, Abe was already in his twenty-eighth season. He had grown the franchise from a ragtag band of barnstormers who sometimes slept in Abe’s car to the most recognized name in the game. They were champs of the pre-NBA World Professional Tournament, and consistently beat a traveling troupe of former college All-Americans in what was dubbed the World Series of Basketball.

Another watershed moment occurred in 1948, shortly after Jackie Robinson had broken through baseball’s color line. The Trotters challenged and defeated the mighty Minneapolis Lakers and their six-foot-10 superstar center, one George Mikan. Fans wondered if the showboating Trotters belonged on the same court; they did. More than 17,800 witnessed a tense and thrilling 61-59 Trotter win at Chicago Stadium. Ermer Robinson’s winning shot burned the net an instant before the buzzer sounded.

Dispelling any idea that the outcome was a fluke, the Trotters beat the Lakers again the next year, 49-45. This time, it was in front of more than 20,000, and they had a comfortable enough lead at the end to perform a few of their reams. Not only did they humble the Lakers on the court, they “put on the show” against them. Millions more saw it the following week on Movietone newsreel footage in theatres across the United States. The Harlem Globetrotters had arrived. They had made it not merely as entertainers, but perhaps as the best team in all of basketball.

The Generals had been the Globetrotters’ regular opponent in the U.S. and world tours since the 1952-53 season. Previously, Abe’s squad played against whatever opponent was available. As a result, the Trotters often thrashed a squad of overmatched locals. This did not make for great community relations or for ticket sales on a return visit.

Abe knew Red Klotz was the right man with whom to forge a good working relationship. He became acquainted with Red as a man who shared his deep passion for the game, strong sense of responsibility, and the understanding of what made a good Globetrotter show. Initially, he had seen Klotz perform for the Philadelphia Sphas in back-to-back wins over his team in 1942, and an overtime battle when Red was coaching the Cumberland (Maryland) Dukes of the All-American League. Over the years, he also faced Saperstein with the Sphas’ touring team and the U.S. All-Stars squad. He knew Klotz always came to play and to press the Trotters to be at their best. At the same time, Red knew why people were buying the tickets, and he never got in the way of a ream. However, that didn’t mean the Generals would roll over. “We were going to make them earn every field goal and make them respect us.”

The Generals’ formation was the start of a very strong professional marriage. “Abe and I understood one another. He knew I would never miss a date and that we would be excellent representatives of the United States overseas. We didn’t have guys who got into trouble. If one of my guys did, I sent them home.”

The State Department took notice and saw the chance for the group to serve as informal ambassadors. They were asked to play behind the Iron Curtain in Berlin, Germany, and across North Africa. It happened again in 1955 in the political and religious tinderbox of the Middle East.

Abe, always up to the challenge, was a patriot who answered his government’s call. He was also an inveterate traveler who loved seeing new places, and experiencing new cultures. The more exotic the locale, the more eager Saperstein was to take his Globetrotters and Red’s Generals. For his part, Klotz was excited to grow his organization and to see the world himself.

As he came off the Generals’ first trip to Israel that summer, Red wrote to his wife Gloria in Atlantic City: “State Department met us here after the Iranian Air Force picked us up in Bagdad, Iraq in old C-47 paratroop planes,” he penned on the stationery of Tehran’s Darband Hotel. Six days earlier in Libya, he wrote: “Feel fine although the heat is terrible. The government of the USA asked us to play in Iran and Iraq. It’s only 125 degrees there and going up.”

The action was hot on the court, also. Among other stars on the ‘55 squad, the Globetrotters featured Reece “Goose” Tatum. A six-foot-four forward and the original “Clown Prince of Basketball,” Tatum was one of the most famous names in the sport, having played a pivotal role in the defeats of Lakers and entertained tens of thousands with his comedy antics. The Trotters also had seven-foot future NBA star Walter Dukes, dribbling ace Leon Hillard, and Robinson, whose long shot proved to be the game winner in the first meeting with the Lakers.

Klotz had a star-packed roster as well. The Generals were an attraction in their own right, with former University of Kentucky All-American Bill Spivey, a seven-foot center who could launch ferocious drives to the basket and shoot with either hand. He led his team to the national title and seemingly was headed to the NBA until his name surfaced in a point-shaving scandal. Despite being cleared of all wrongdoing in a jury trial, Spivey was banned for life from the NBA by Commissioner Maurice Podoloff.

The NBA’s loss was the Generals’ gain. In Klotz and Spivey, Washington had the best high-low combination in pro basketball at the time. They also had Fred Iehle the six-foot-three forward from LaSalle College, the 1953 MVP of the National Invitation Tournament, and Curt Cuncle, and, a six-foot-three forward from the University of Florida via San Antonio, Texas. Cuncle had been named to the first team Associated Press All American team. Two hard-nosed six-foot-three brothers from Jackson, Tennessee named Tom and Bill Scott rounded out Klotz’ formidable top six players.

On the 1955 pro basketball scene, there was the nine-team NBA, and there were the Harlem Globetrotters. There were also the Washington Generals. Despite losing every night and sometimes twice a day, the Generals were one of the 11 best teams on the planet. “People don’t think of it that way because we lost, but that was definitely the case,” Klotz said. “We could play with pretty much anybody.”

Bragging rights and a loaded roster did Klotz no good without the basketballs needed to play. Where were the balls? Klotz thought again and realized the bag was most likely where he last saw it, on the team bus. With a shrug, he headed back toward the vehicle. Knowing time was short, he broke into a jog.

The bright red carpet leading from the court to the Shah of Iran’s viewing booth lay in Klotz’ path. Red didn’t know it, but the carpet represented some kind of demarcation line for the no-man’s-land in the eyes of the Shah’s elite armed guard.

Red: “I got to the carpet, and the crowd became hushed. It was dead silent. And then there was this ear-piercing scream from someone in the crowd. It was like something out of a horror picture. It was a scream that could’ve made your blood run cold. The next thing I knew, I found myself staring down the barrels of the guards’ rifles. You could say people were a little on edge.”

Klotz stopped running, inches short of the guns. “Somebody points a gun like that at you, it gets your attention,” he said. “One more step, and they might have turned me into a big piece of Swiss cheese.”

If Red was terrified, he may have been the only one among the American delegation. “I looked back at the benches, and the Trotters and all my players were doubled over, laughing! They were hysterical. It was quite an amusing moment, at least for them.”

Klotz convinced the guards he was not an assassin and that the balls were necessary if the Shah was going to get the show he came to see. From that point on, everything worked out well for the second game in Iran. “We lost the game, the Trotters were great, the crowd loved it, and the Shah was not harmed. Oh yes… and nobody got killed.”

Red (top row, third from left) poses on camelback with members of the Washington Generals and Harlem Globetrotters in Egypt, 1955. Abe Saperstein is in the white captain’s hat front and center.

Louis Herman Klotz with basketball, age 2

Chapter 2

Philly Ball

The basketball journey of Red Klotz begins in South Philadelphia, some 6,208 miles from the site of his “almost” international incident in Iran. Asked about his initial encounter with the game, he pokes fun at his longevity: “My first shot was at a peach basket nailed to a wall by Dr. James Naismith.”

Though sometimes given to hyperbole to make a point, Red’s stock answer isn’t that far off. Naismith, the game’s inventor, published his Rules of Basketball in 1892, less than 30 years before Klotz was born. As a child, peach baskets were still a common sight on makeshift courts all over his neighborhood and many other urban areas of the Northeast. By the time Klotz became a star player at South Philadelphia High School in the late 1930s, Naismith still was active in the sport, helping to found the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball.

Klotz’ actual first shot may not have been aimed at a Naismith-installed goal; however, it was memorable in its own right and would serve as a metaphor for his seemingly charmed life in the game.

Growing up in South Philly during the Great Depression, neighborhood kids played every kind of game imaginable, and some imagined on the spot. If there was a ball, there was a game: step ball, wire ball, wall ball (also known as “chink”), one-bounce, and half ball. Most were variations of baseball modified for the narrow confines of Philly’s row-house-lined streets. Kids also played sandlot football and baseball wherever they could find room.

One day, young “Reds” Klotz – the nickname would be shortened to Red some years later – was chasing an errant football that had bounced onto the basketball court at George J. Thomas Jr. High School at Ninth and Oregon Avenues. A since-forgotten playmate flipped the basketball to Red and invited him to give it a try. Never shy to join in a game of any kind, young Red heaved the round ball toward the hoop. It came down cleanly through the cords, making that distinctive sound he would hear countless times in the future. “This game is easy,” thought the then eight-year-old. He soon would learn quite differently. To excel at the game would require countless hours of practice and many scrimmages. Still, basketball intrigued him from the very start.

“I just fell in love with it…the physical nature of the game, but also the mental side,” he said. “I liked the fact that you could have a game with your friends, and also that you could work out by yourself and improve. All you needed was a goal and a ball. You know that story about the kid who wanted to play so badly he shoveled snow off the court? That kid was me! There was more than one time I cleared snow from a court. I’d play all day, and when it got dark, I’d go to the end closest to the streetlight until I got used to it. I think that helped me develop an actual feel for the game. Later, when I became very nearsighted, so nearsighted I couldn’t read the scoreboard clock, I could always find the basket. I had practiced and played so much under so many crazy conditions that I could feel comfortable around any court, the basket, and of course, the ball.”

Basketballs of that era had laces on one of the seams, similar to footballs. “If I was open for a shot, I got to be pretty good at spinning the ball quickly to where the laces would be at my fingertips. It gave me more control when I shot it.”

Virtually all players of that era used a two-hand set shot. Klotz shot that way his entire career and as a recreational player into his 90s. He could dominate games with that shot against players 65 years his junior. “The game has changed so much,” he says. “It was much more of a passing game as opposed to all the dribbling today. A few things haven’t changed, though. The best teams and the best players are masters of the fundamentals.”

Though still relatively new, basketball was a solidly established “city game” when Klotz was growing up. Its birthplace is claimed by Springfield, Massachusetts, and the Canadian-born Naismith earned his coaching chops in the Great Plains at Kansas University, but it was the cities, particularly New York City and Philadelphia, which were ground zero for the explosion of the game’s popularity. The game was well-suited for the confines of the streets, small clubs and gyms, settlement houses, YMCAs and YMHAs, and the schools of the urban areas. The Jewish sons of immigrants were among the best players, while the Irish, Germans, Polish and Italians also were well-represented on the playgrounds. “In our neighborhood, there were many Jews, and just about every other group, too. There weren’t many blacks in that area at the time. They were concentrated in other areas of the city. Still, it was a pretty good example of the ‘melting pot,’ right within a few blocks of our house.”

Professional ball was already in existence and gaining a following in those cities. Many of the best players were Jewish, coming out of pickup games, school teams, and community leagues in predominantly Jewish areas. African Americans had discovered the game as well and became quite proficient, though not in the same numbers as the Jewish players. The New York Renaissance, or “Rens,” was the first well-known and accomplished all-black pro squad. Philadelphia’s Sphas (an acronym for the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association) were all Jewish and won championships in several pro leagues.

Red Klotz was all of six years old when in Chicago, a Jewish immigrant named Abe Saperstein founded another all-black team he called the New York Harlem Globe Trotters, despite the fact they hadn’t set foot very far East of the Windy City, much less Harlem. The Trotters had great players, such as “Runt” Pullins and Inman Jackson. Ultimately, with their name shortened to Harlem Globetrotters, they would achieve great success through Saper-stein’s sports and entertainment innovations.

However, the team’s foundation for that success began with skillful play on the court. They beat almost all of the local teams before Saperstein began barnstorming the far West in his beatup Model T Ford. When the nation’s banks began to fail in 1929, Abe made the decision, “to take the team where there were no banks.” It began a lifetime penchant for exploring new and exotic locales.

Pro basketball, though firmly established, was not yet considered a major sport, and the teams’ exploits earned little space in the daily newspapers of the day. Baseball was tops (Philadelphia had two major league teams, the Athletics and Phillies). Boxing and horse racing were the other top spectator sports, followed by college football. “Pro” basketball players of that time earned a few extra grocery dollars but not a living. Everyone had a day job, and games were played mostly on weekends. However, to a star-struck boy growing up playing in the shadow of some of the sport’s early pioneers, there was no better place to be. Klotz’ Jewish parents had emigrated from Russia to an area with a strong Jewish presence, along with many other ethnic groups.

“Harry Litwak was my idol,” Klotz said of the Sphas’ star player, Philadelphia Warriors assistant coach, and longtime head coach at Temple University. Litwak was a South Philly native like Klotz and is enshrined in the Hall of Fame. “We thought of the Sphas the way kids today think of the Lakers or the Celtics. They represented the best. We wanted to be just like them.”

Though Klotz didn’t realize it at the time, he was learning the game in a true cradle of the sport. Not only was South Philly home to Litwak, the schoolyard at Thomas Jr. High where Red sank that first basket was the workplace just a few years earlier of a Russian immigrant gym teacher born Isadore Gottlieb. He would become much better known as “Eddie,” cofounder of the Sphas, organizer, coach, and owner of the Philadelphia Warriors, and one of the original executives of the Basketball Association of America, which became today’s NBA. He was also an owner of the Philadelphia Stars baseball team of the Negro Leagues, and a promoter of boxing and wrestling matches, semi-pro football games, and even women’s baseball. A born promoter, Eddie was associated most closely with basketball and would become known as one of the sport’s premier judges of talent. Red had absolutely no clue that one day in the not-too-distant future, Gottlieb would sign him to his first pro contract.

Time only has enhanced Philly’s reputation as a basketball Mecca. The foundation laid by the Sphas was built upon by Gottlieb’s efforts to found the NBA. He was instrumental in starting up Philly’s first NBA franchise and the league’s first champions, the Philadelphia Warriors.

Philadelphia was also the birthplace and home of arguably the greatest player ever, Wilton Norman Chamberlain. The “Big Dipper” would bring international attention to the city beginning in his days at Overbrook High School in the mid-50s. At just under seven feet, two inches, with the physical dexterity of a much smaller athlete, Chamberlain not only would revolutionize how the game was played, he would usher in the era of the “big money” athlete and the concept of basketball superstars as major national celebrities.

Philly is also home to six thriving Division One college basketball programs, more than any city in America. In addition to Drexel, which competed in a variety of Middle Atlantic Region leagues over the years, the city series league called the Big Five consisted of LaSalle, Pennsylvania, Temple, St. Joseph’s, and Villanova. It would be in this nurturing basketball environment, perhaps the strongest in the world, that Red Klotz would develop his game, learn its many nuances, and ultimately carve out his own niche and contribute to the growth of basketball as much as anyone.

Louis Herman Klotz was thought to have come into the world on October 21, 1921. The birth certificate, located by his son Glenn more than eight decades later, would list a birth date of October 23. The certificate doesn’t say exactly where, but the best guess is that the birth took place in the family’s row home on Darien Street. A delay in the issuance of paperwork may have been responsible for the disagreement on the precise date.

Robert and Lena Klotz were the parents of two older sons, Joseph and Samuel. A sister had fallen victim to a flu epidemic that swept through the city in 1918. The so-called Spanish flu killed more than 12,000 people in Philadelphia alone, according to The New York Times. Officials speculated that large public gatherings such as a World War I loan drive rally may have caused the “bug” to spread so quickly.

In his earliest known baby picture, two-year-old Red is seen clutching a ball. “I was crying until the photographer handed me the ball…I stopped immediately. He kept trying to take it away from me, because he didn’t want the ball to be in the picture. Each time he tried that, I began to cry again, until he finally gave up and let me hold onto it. As if on cue, I stopped crying, and he was able to take the picture.”

When he wasn’t in school, running errands, or doing the occasional odd job, Red’s parents knew they either could find him out in the street, playing one of the aforementioned games, or at the Thomas Jr. High playground. Robert was too busy earning a living and serving his community as a volunteer firefighter to scrutinize the play habits of his three boys. Mom was a different story. The tragic loss of her baby girl had made Lena highly protective of Red, the youngest and smallest of the brood.

“My mother was a wonderful woman, kind and caring and thoughtful of all her children and my dad before herself,” Klotz recalled. “When it came to me and the idea of playing sports, she didn’t like it. She thought I was going to get hurt. She was always trying to put a sweater on me or fussing over the state of my health. She never embraced the idea of me as a ballplayer. She didn’t even know I was a real player until my name began showing up in the papers and people would tell her about it.”

In 1929, around the time Red sank that first shot, the bank failures that sent Abe Saperstein Westward in his Model T eventually led to an historic stock market crash and a scarcity of jobs. While Red was making his own fun with a variety of ball games, it wasn’t much fun to be an adult during the Depression that lasted until World War II. Robert Klotz, a master carpenter and cabinetmaker, was much more fortunate than most. His skills were in demand, even during the lean times. “My dad was always able to keep food on the table,” Red recalls. “We were not rich by any means, but my brothers and I never went hungry. We had decent, clean clothes, though mine were mostly handed down.”

Like most immigrants who never looked back after taking the bold step of leaving family and friends to forge a new and better life in America, Robert Klotz embraced his new country and impressed his offspring with the importance of patriotism. His willingness to put his life on the line as a firefighter and to help out wherever possible at neighborhood functions backed up his words. Robert and Lena fled the pogroms, a ruthless campaign of violence led by the Czar’s organized forces against innocent Jews. “My Dad never really spoke about the dangers he faced or all of the horrible things he saw,” Red Klotz said. “He did make it very clear it had been a life and death decision. He was a very happy and considerate man with a great sense of humor. He didn’t concentrate on a bad situation he left behind. It was about raising his family in a wonderful country that embraced all the groups, and to have settled into a better, peaceful life. He believed in the ideal that America was known as the land of opportunity.”

The better life certainly included the very American concept of leisure time and the good old American road trip. “We had a Model T, and Dad always scraped enough together to spend a week or two every summer in Atlantic City. The car would break down, flat tires and the like, and we still always made it there and back (about 130 miles round trip).”

“Dad would stop the car along the way at one of the many roadside farm stands and markets in South Jersey. He would give us delicious fresh fruit to eat. Then we would finally arrive in Atlantic City and there would be the ocean. I thought it was wonderful, and I still do. The ocean gives you a different view every day. To walk along the beach…it clears your mind. When it was time to leave and go back to the city, I wasn’t too happy about that. I always liked the seashore a lot better.”

Seeing the beach, ocean, and bright lights of the boardwalk and its many entertainment piers, smelling the salt-scented air and feeling the fine white sand between his toes proved exciting. Red’s world previously consisted of concrete, tall buildings, row houses, and the smells of Philly’s industrial heyday. No disrespect to his biological hometown, Red always insists. It was just that this was the start of a lifelong love of the Jersey Shore. Atlantic City and environs would be where he would meet Gloria, his future wife, where his six children would be born and raised, and the place he considered to be his adopted hometown. For the present, though, Atlantic City was merely a respite. Robert would return and resume practicing his tremendous work ethic. Lena would tend to the kids and Red would return to school, errands, and lots of street games, especially basketball.

His newfound passion translated to more playing and more improvement to his game. Before long, he outgrew the games at Thomas Jr. High. The neighborhood kids were great friends, but not at the same level basketball-wise. This being South Philadelphia, Red didn’t need to travel very far to find the challenge of stronger competition. One such facility was an indoor “cage” court at Fifth and Bainbridge. Many such wire mesh courts were still in use at the time, a throwback to when “cagers” were the norm among basketball players. The cage itself was in bounds during games, and bloody injuries were common as players dove after loose balls or were shoved into the sometimes jagged and rusty metal.