Irish Business and

Society

Governing, Participating and

Transforming in the 21st Century

GILL & MACMILLAN

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction: Reflections on Issues in Irish Business and Society

John Hogan, Paul F. Donnelly and Brendan K. O’Rourke

Section I The Making and Unmaking of the Celtic Tiger

1. Labour and Employment in Ireland in the Era of the Celtic Tiger

Nicola Timoney

2. Politics and Economic Policy Making in Ireland

Frank Barry

3. Forming Ireland’s Industrial Development Authority

Paul F. Donnelly

4. Enterprise Discourse: Its Origins and its Influence in Ireland

Brendan K. O’Rourke

5. The Politics of Irish Social Security Policy 1986–2006

Mary P. Murphy

6. Need the Irish Economic Experiment Fail?

William Kingston

Section II Governance, Regulation and Justice

7. A Review of Corporate Governance Research: An Irish Perspective

Niamh M. Brennan

8. Corporate Social Responsibility in Ireland: Current Practice and Directions for Future Research

Rebecca Maughan

9. White-Collar Crime: The Business of Crime

Roderick Maguire

10. Political Corruption in Ireland: A Downward Spiral

Gillian Smith

11. Lobbying Regulation: An Irish Solution to a Universal Problem?

Conor McGrath

12. A Social Justice Perspective on the Celtic Tiger

Connie Harris Ostwald

Section III Partnership and Participation

13. Economic Crises and the Changing Influence of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions on Public Policy

John Hogan

14. Partnership at Enterprise Level in Ireland

Kevin O’Leary

15. From Ballymun to Brussels: Forms of Partnership Governance in Irish Social Inclusion Policy

Jesse J. Norris

16. People in Control: The Promise of the Co-operative Business Approach

Olive McCarthy, Robert Briscoe and Michael Ward

17. Emotional Intelligence Components and Conflict Resolution

Helen Chen and Patrick Phillips

18. Regulatory Framework: Irish Employment Law

Mary Faulkner

Section IV Whither Irish Borders? Ireland, Europe and the Wider World

19. Ireland and the European Union: Mapping Domestic Modes of Adaptation and Contestation

John O’Brennan

20. Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: A Changed Relationship

Mary C. Murphy

21. Cultural Tourism Development in Irish Villages and Towns: The Role of Authenticity, Social, Cultural and Tourist Capital

Breda McCarthy

22. Twenty-First-Century International Careers: From Economic to Lifestyle Migration

Marian Crowley-Henry

23. Achieving Growth in a Regional Economy: Lessons from Irish Economic History

John McHale

24. The Europeanisation of Irish Public Policy: Theoretical and Comparative Perspectives

Kate Nicholls

Section V Interests and Concerns in Contemporary Ireland

25. Access and Expectation: Interest Groups in Ireland

Gary Murphy

26. Civil Society in Ireland: Antecedents, Identity and Challenges

Geoff Weller

27. The Practice of Politics: Feminism, Activism and Social Change in Ireland

Jennifer K. DeWan

28. Alcohol Advertising in Ireland: The Challenge of Responsibility and Regulation

Patrick Kenny and Gerard Hastings

29. Children’s Interaction with Television Advertising

Margaret-Anne Lawlor

30. Do Modern Business Communications Technologies Mean a Surveillance Society?

Karlin Lillington

31. Spirituality, Work and Irish Society

John Cullen

Contributors

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Praise for Irish Business & Society

Copyright Page

About Gill & Macmillan

Introduction: Reflections on Issues in Irish Business and Society

INTRODUCTION

In this introductory chapter we will put the book and its aims in context and provide the reader with a guide to the wide-ranging, diverse and thought-provoking contributions contained between its covers. In order to do so, this chapter is structured as follows. The first section looks at the context within which this book finds itself and which makes its appearance particularly apposite. The second section deals with the aims of the book as we editors have come to conceive of them. We then provide the reader with an overview of the book’s themes and structure.

CONTEXT

The first decade of the twenty-first century has witnessed a swing from the apparently triumphant thirty-year march of deregulated business to the seemingly necessary, and very expensive, rescue by a state and society of ‘private’ companies that are now judged to be too big to be allowed to fail. It would seem that the doctrine of free market capitalism is now suffering the same loss of faith that the doctrine of communism suffered during the 1970s, when the price of maintaining stability and the status quo was social and economic stagnation (Rutland 1994:xi). Given the failures of these ideologies of the past to deal satisfactorily with either the narrower economic problems or the wider concerns of society, trying to gain an understanding of business and society appears a daunting prospect beset with numerous difficulties, but a challenge that nevertheless must be risen to.

Over the past half century, relations between Irish business and society, how they are governed, and how participation in business and society is exercised, have been tested, challenged and transformed. Currently, Ireland, along with the wider global political economy, is struggling to deal with the consequences of the worst international economic downturn since the end of the Second World War, while Ireland itself is also trying to come to terms with the implosion of its house price bubble and its wider implications. Although this is a period of unprecedented economic flux, exogenous shocks and, to some extent, internally generated crises, are nothing new to Ireland and its small open economy. We have weathered such events in the past, and, no doubt, will have to do so again in the future. It is what we have learned from our previous experiences, and can bring to bear in our dealings with current events, that is of crucial value.

Although the business and societal structures that enabled Ireland achieve great economic success over the past two decades are still in place, a series of questions now faces the country: Are these structures still fit for the purposes they were initially designed to address?; Can they be adapted to the new reality of the changed world?; Or do they need to be revised, or even discarded, in favour of something radically different? The end of the first decade of the twenty-first century is an ideal time to take stock of the state of business and society in Ireland.

An Increasingly Integrated and Dynamic Society

Given the world in which we live today, Ireland is home not only to Irish businesses but also to foreign businesses and investments. Further, business in Ireland is answerable not only to Irish society, but also to societies beyond the country’s borders, for Ireland has become one of the most open and globally integrated economies in the world following the policy decision, taken in the late 1950s, to embrace free trade.

With this in mind, it is helpful to recall that business has responsibilities to society, as determined by society itself, for business exists at the pleasure of society and its laws: notwithstanding the status of legal personhood granted to businesses over the decades, it is society that grants them a licence to operate and it is society that can withdraw such permission. As noted by Cadbury (1987:70), ‘[b]usiness is part of the social system and we cannot isolate the economic elements of major decisions from their social consequences’. Thus, Cadbury (1987) argues, it is society that sets the framework within which business must operate, with responsibilities running both ways: business has to take account of its responsibilities to society, while society has to accept its responsibilities for setting standards to which business must conform.

Indeed, at the 2010 World Economic Forum, questions were asked not just about the failings of bankers, but about the kind of society we wished to have, with French President Nicolas Sarkozy calling for a ‘deep, profound change’ in the wake of the financial crisis and saying he wished to restore a ‘moral dimension’ to free trade. In asking ‘what kind of capitalism we want’, Sarkozy asserted the need to ‘re-engineer capitalism to restore its moral dimension, its conscience’, for ‘[b]y placing free trade above all else, what we have is a weakening of democracy’ (BBC News 2010).

Looking back in time, we have our understandings of the 1929 crash, and the events it precipitated, culminating in the Great Depression, to help us in reflecting on what we are experiencing today. It is useful to recap the conventional learning from that period. The stock market crash was built on easy credit, exuberance and a light to non-existent regulatory regime. To all intents and purposes, when it came to regulation, ‘the market’ was seen to reign supreme and it was the market that would act as a self-regulating mechanism. However, the market failed, the stock market crashed, banks collapsed and a vicious cycle of business bankruptcies, unemployment and falling demand kicked in and all began their spiral downwards. In the USA, the Republican government of the time stood on the sidelines and did nothing to intervene. It was only after the election in 1932 of Democratic Party candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president that the government started to act, putting in place regulations aimed at preventing the mistakes of the past happening again. Globally, the fallout saw protectionism replace free trade and helped fan the flames of anti-capitalist movements. In some countries, the unemployed masses, in their desperation, turned to nationalist movements and demigods for salvation, the most notorious of these being the Nazi movement in Germany. Thus, the Great Depression contributed to the circumstances that led to the outbreak of the Second World War. It was only in the wake of that conflict that tentative moves towards free trade were initiated with the conclusion of the first General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1948. Or so received wisdom tells us.

Today, it seems that, as in the Great Depression, governments and central banks throughout the world are intervening to contain the impact of the credit crunch. Society is once again bearing the brunt of the resultant fallout through unemployment, increased national debt, increased taxation, decreased public services, etc. And there is the uncalculated, and perhaps incalculable, human cost in terms of the knock-on effects of unemployment: the time lag in regaining employment; the impact on the person of being unemployed and seen as an unproductive and draining member of society; the cost to families in terms of children possibly not being in a position to achieve their potential through decreased levels of access to opportunities for learning; and so on.

If anything, and leaving aside the myriad lessons that are almost daily presented the world over in terms of the actions of business in society, the mistakes that precipitated both the Great Depression and today’s global recession highlight the importance of understanding business and society in context, of perceiving business as part and parcel of society and of not seeing society as subservient to business. Furthermore, business cannot be seen to operate outside society, as if society does not matter; rather, business must be seen as one part of the jigsaw that constitutes society.

What is perhaps most telling of all is that the majority of business and political leaders never saw, indeed failed to see, either the Great Depression or the current global recession coming. On both occasions, the mantra ‘this time it’s different’ rang out as it has many times before (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). Each time, we were told that we were experiencing a new era in finance and capitalism. We can but wonder whether lessons will finally be learned this time around. In the meantime, none of us, including the so-called ‘experts’ on whose words we hang as we look to make our way out of the current debacle, has a crystal ball to foresee the future. Rather, we are now engaged in constructing our future, with the shock of the recession providing us with an opportunity to create the kind of society that, this time, might just see the re-engineering of capitalism with a conscience and a moral dimension.

THE CHALLENGES OF A CHANGING SOCIETY

In all of this, whither Ireland? Where does this leave us and how we see Irish business and society moving forward? Context is important and, while it is crucial not to be constrained by the past, it is just as important to build a sense of where we have come from so that we can be more informed about where we wish to go. As such, with an opportunity to reflect and an eye to the future, the chapters of the book provide us with some of the context necessary to question and inform our perspective of business, society and the intersection of the two.

We are not dealing with a static picture; rather we are confronted with an ever-changing context, one that is complex and multi-faceted. Also, we are not living or operating within a vacuum, either in terms of business in relation to society, or Ireland in relation to the world. Rather, business is an integral part of society and Ireland is an integral constituent of the global political economy. Indeed, given how open we are as an economy, we are very much influenced by events across the wider world, and what we do also has a bearing upon the world, however small that impact might be.

Ireland has very firmly pitched its tent as welcoming inward investment, so much so that it is recognised as one of the easiest countries in which to do business: it is ranked seventh of 183 countries, and third in the European Union (EU) (World Bank 2010). Meanwhile, trust in government and business in Ireland is not just at an all-time low; it is the lowest of all twenty-two countries surveyed in Edelman’s 2010 Trust Barometer (Edelman 2010), with just 31 per cent of those surveyed trusting business and 28 per cent trusting government (compared to a global average of 50 per cent and 49 per cent respectively). Indeed, trust in the institutions of government and business in Ireland has been on a downward trend since the 2007 survey, underlining a potentially deep institutional scepticism. In addition, two-thirds of Irish respondents to the 2010 survey consider all stakeholders (including government, employees, customers, society at large and investors/shareholders) equally important to a chief executive officer’s (CEO) business decisions, compared to half as important in the EU countries surveyed. Overall, Edelman (2010) drew a number of conclusions from the global 2010 barometer that are pertinent to where we are today and going forward. In particular, Edelman found that profit has become the least important criterion in assessing corporate reputation, being superseded by performance on a number of measures, including transparency and role in society, and there has been a swing away from a singularly shareholder view to an encompassing stakeholder view.

Given this, a greater understanding of the linkages between business and society, and how these change and evolve, will enable a better appreciation of contemporary Ireland, and how it has come to be currently constituted. Within less than a generation, Ireland has gone from being one of the countries with the lowest income in Europe to having one of the highest (Haughton 2008). This transformation has brought great prosperity in its wake. However, such prosperity is rarely shared equally across the whole of a society. As a result, problems have arisen in terms of inequality of incomes, opportunities and quality of life. As the Celtic Tiger era fades into history, what kind of society has it left behind? Debates about the problems of equity and fairness in our society, suppressed to some extent by the euphoria of new-found prosperity over the past decade, in particular, have now taken on a renewed relevance as the dole queues have once more lengthened and others leave the country in search of work abroad.

How Irish businesses are governed, and how they participate in society, has changed radically in recent years. The level of responsibility of business to society, and what society expects of its businesses, has also undergone a transformation. The relationships between business and government, in particular, have come under renewed scrutiny in light of the house price bubble collapsing and the banking sector crisis. This led to calls for increased regulation of business, particularly in the financial sector, increased enforcement of such regulations, and increased regulation of business and government relations. A rethinking of the responsibilities of Irish businesses to the wider society will be necessary if the country is to maintain its economic competitiveness, as well as its credibility as an investment option for foreign businesses into the future. The issue of cronyism in the upper echelons of our society is also something that we, as a people, have to confront. We are a small country, so the potential for the existence of cronyism should not come as too much of a surprise, but what we do to combat this, and its negative impact on society as a whole, is critical.

Society has increasingly sought to set the bar higher for businesses in terms of the standards it expects of them, and, as a result, businesses have been forced to take on board considerations that received scant attention in the past, such as protecting the environment and ethically sourcing supplies. Basic economic measures of business performance are no longer sufficient to capture the whole of the role these organisations play in our society, as their responsibilities towards society now encompass achieving more broadly shared goals.

The relationships between business and society must also be understood within the context of the wider political economy. At the start of the twenty-first century, Ireland finds itself located at the edge of an increasingly integrated European continent. Where a century ago Europe was moving inexorably towards war, today the continent seems more peaceful and contented than at any time in its long history. Being one of twenty-seven member states of the expanding EU, Irish business and Irish society are presented with a vast range of opportunities and challenges that earlier generations could not have imagined: opportunities in the form of what increasing integration within the EU represents in terms of markets for Irish businesses, and freedom of movement for citizens and capital; but also challenges in terms of the increased levels of competition confronting those same businesses. As a society, we are also having to face up to what it means to be a sovereign state when some of our autonomy is gradually being yielded to EU institutions, while economic sovereignty, in the form of policies running counter to those of our competitors, or to the expectations of the international financial markets, has also been greatly diminished. This has led to new kinds of thinking about the relationships between citizens and their society, workplace and government. For instance, what does it mean to be an Irish citizen and an EU citizen, when the EU stretches from Galway, in the west of Ireland, all the way to Narva, on the border with Russia? No longer can any one society, or its businesses, seek to exist in splendid isolation.

The Celtic Tiger era, a period of unprecedented growth, has left many questions in its wake. From seeking answers to these questions, we can draw a range of lessons that might enable us to manage our economy and society in a better and more equitable fashion, once the recession ends and economic expansion returns. Thus, the contributors to this volume examine the state of Irish business and society today and, in this light, contemplate how it might develop into the future.

AIMS AND USES OF THIS BOOK

The main aim of this book is to provide readers with a wide-ranging understanding of the debates surrounding the relationships between business and society in twenty-first-century Ireland. The decisions that businesses make all have a social impact, from production decisions to efforts to influence government policies. As such, Irish business constitutes a fundamental element within Irish society, making it a major social actor. But if business occupies such a position in society, what obligations does it have to society? And, how do these obligations square with what many see as its profit-maximising raison d‘être?

Of course, given the contexts we have discussed, it is not surprising that we are not the first to produce a volume on such issues. Internationally, many fine minds, struggling to grapple with the problems the world now faces, have in the last few years presented their solutions in the form of best-selling books addressing global business and societal issues (e.g. Kinsley 2008; Reich 2008; Sen 2009; Stiglitz 2010; Wilkinson and Pickett 2009).

This volume addresses Irish society, with its own unique culture and institutions. Just as on the global stage, there have been a considerable number of Irish books on this topic in recent times, both from individual authors (e.g. Allen 2009; Cooper 2009; O’Toole 2009) and from particular disciplinary perspectives (e.g. O’Hagan and Newman 2008; Share et al. 2007). What this volume adds to the debate on business and society is the presentation of a variety of disciplinary perspectives from leading business researchers, economists, sociologists and political scientists. Within its covers are contained thirty contributions from thirty-five authors based in a wide range of institutions of higher learning from across Ireland and beyond. Thus, this collection represents a significant set of resources from which the reader can draw.

This volume seeks to break down the barriers that separate and isolate disciplines, such as sociology, economics and politics. The intention is to provide the reader with an encompassing understanding of national and international issues and events and to facilitate intellectually challenging and honest dialogue between viewpoints that often remain isolated from each other. As the issues discussed in this volume will be of interest to a broad spectrum of academic disciplines, in addition to professional and general readers, the various contributors have made their works as open and accessible as possible, while still grounding them in the rigour that such studies require. One of the primary intentions in putting together this edited volume is to disabuse readers of the often-voiced misconception that there must surely be one best discipline to provide us with a comprehensive understanding of a business or societal issue. The contributors to this book use an array of approaches from a variety of disciplines to examine and understand problems.

Therefore, readers from a range of disciplinary backgrounds should be able to use this book as a wide-ranging text on Irish business and society, something that has been sorely lacking until now. Additionally, they should find the book helpful in complementing some of their discipline-specific readings and texts on business, economics, sociology and politics in Ireland. Our hope is that readers will see that it is through questioning our society, its structures and institutions, and by holding a mirror up to them, that we can improve matters for all. Problems in society are not only issues that have to be solved and resolved, they also contain lessons – lessons that we can learn from, and in so doing, avoid having to repeat mistakes into the future.

THEMES AND STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

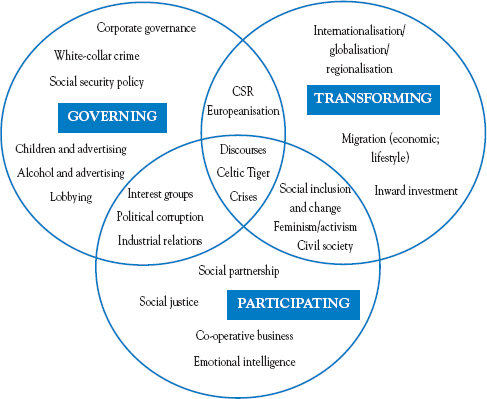

As already noted, this volume presents a series of unique insights into various aspects of Irish business and society. The volume title in itself suggests a number of overarching themes, namely governing, participating and transforming. The use of the gerund here is deliberate, for it underscores that what we are dealing with is not static; rather it is dynamic, with change ever present. The use of the gerund also underscores that these over-arching themes point to and incorporate the past, present and future. Figure 1.1 represents but one way of organising the various themes of the book’s chapters.

Figure 1.1 Overarching themes and allied sub-themes of this book

To make managing these resources somewhat easier, the book has been divided into five main sections, each containing a series of interrelated chapters. The chapters themselves are relatively short, but captured within each is the insight of a specialist’s expertise, and their unique understanding of, and perspective on, a vital aspect of Irish business and society.

Each of the five sections examines an overarching theme, or set of themes, through a variety of disciplinary lenses, thus providing both a macro and a micro perspective on the chosen topic. Each chapter, as a self-contained unit critically examining a topic in Irish business and society, also constitutes an aspect of the greater whole, much as each institution within a society is also part of something bigger and, as such, must be appreciated with this contextual understanding in mind. Altogether, the approach we have adopted provides the reader with an inclusive and rounded understanding of how business and society has evolved and developed into how it is today.

An essential element of all the chapters is that they are intellectually honest. This may mean facing up to certain unpleasant truths about our businesses and our society, and, where the contributors judge it necessary, this is done unflinchingly. Thus, the reader is presented with a book that constitutes a relatively diverse presentation of aspects of Irish business and society.

All the contributors to the volume are writing from their own areas of expertise. But they also recognise that, as this is a multidisciplinary text, the presentation of their arguments must be as accessible as possible to a wide spectrum of readers. The various chapters show how there are multiple ways in which to examine issues in society. This highlights how each discipline has its own take on society, but also how these understandings can intersect.

Turning to the content of the book itself, Section I, spanning Chapters 1 to 6, contains an examination of the making and unmaking of the Celtic Tiger. This is the context in which the relations between business and society have been shaped in recent years. The chapters examine: the changes to the labour market and employment situation in the country in the period between 1988 and 2008; the role played by certain vested interests in policy decisions that have operated against the interest of the wider society; the role played by the Industrial Development Authority (IDA) in opening the Irish economy to outside investors; the specific discourse of enterprise that is particular to Ireland; the politics of Irish social security policy; and, finally, the structural problems in the underlying framework of the Irish political economy. In all, these chapters present a range of views on both the positive and the negative aspects of the Celtic Tiger era.

Section II, comprising Chapters 7 to 12, looks primarily at the issues of governance, regulation and social justice. Companies in Ireland are governed through a complex set of legal and organisational structures. It is these structures that make up the firm’s system of corporate governance. Despite this, a number of large Irish corporations, in particular in the financial services sector, have recently been hit by a series of scandals that raise questions as to their governance structures. These chapters provide a review of: corporate governance in Ireland; the practice of corporate social responsibility in an Irish context; the issue of white-collar crime, and how the legal system has dealt with it; the problem of political corruption; the issue of regulating the growing lobbying industry; and, finally, an examination of the issue of social justice in Ireland. The authors of these chapters argue that much has been done to deal with problems in our business, political and societal institutions, but also that much remains to be done. They also point out that, although Ireland’s recent prosperity brought great benefits to society as a whole, it has also brought other problems in its wake, including issues of corruption, a lack of accountability, and those sections of the community that were left behind during the era of prosperity.

In Section III, Chapters 13 to 18, the overall theme is partnership and participation. Since 1987, a series of tripartite agreements, usually of three years’ duration, have been reached between the government and the social partners – the primary economic interest groups in Irish society. While these agreements were initially seen as a means of correcting the serious fiscal imbalances that had arisen within the economy during the late 1970s and early 1980s, they subsequently took on a broader character, encompassing social policy and addressing issues of equality in society and social justice. These chapters give an overview of: the impact of economic crises on the changing influence of trade unions in Irish society; the workings of the enterprise-level partnership model; the various forms of partnership governance in Irish social inclusion policy; the co-operative approach to business; the role that emotional intelligence plays in resolving workplace conflicts; and, finally, how the law deals with the workplace and industrial relations. The authors of the first three chapters of this section provide a macro, as well as a micro, examination of aspects of the Irish social partnership, how it has evolved, and what the future might hold for it. The latter three chapters examine how society develops its own businesses when public and private interests fail to do so, and how conflicts in the workplace can be resolved by a variety of means.

The book then moves on to considering international issues of relevance to Irish business and society in Section IV, which runs from Chapter 19 to Chapter 24. As Ireland is a small open economy, the international environment has had a huge impact on relations between Irish business and society. In light of the fact that the domestic market is so small, all major Irish companies must export in order to grow, and, in so doing, they must compete with international rivals who are usually from larger economies wherein economies of scale are more easily achieved. The development of the global corporation and the increasing integration of Europe have all impacted upon Irish society. These chapters examine: the position of Ireland in the EU in the wake of two Lisbon referendums, and an EU of twenty-seven member states; the changed relationship with Northern Ireland; the issue of how Ireland presents itself and its culture to the world; the challenges and opportunities presented by the internationalisation of careers, in the context of an increasingly multicultural workforce and society; the economics of migration in Ireland, from both a historical and current perspective; and, finally, rounding out the section, and linking with the section’s opening chapter, is a discussion of the Europeanisation of Irish public policy.

The final section of the book, Section V, which comprises Chapters 25 to 31, looks at interests and concerns in contemporary Ireland. Interest groups, and their input into policy making, constitute a vibrant, vital and integral part of contemporary Irish liberal democracy. In Ireland, in the era of corporatism, interest groups have become part of the policy-making process. They provide another channel by which citizens can present their opinions to government. However, of crucial importance is the strong influence on policy decisions of concern to the whole of society by groups that do not necessarily speak for the broad populace. In particular, these chapters examine the role played by interest groups in Irish society; how civil society operates and its relationship with the state; the changing role and composition of the women’s movement in Irish politics; the issue of alcohol advertising and how it is regulated; the issue of advertising aimed at children; the use of high-technology communication devices in business, and their implications for the development of a surveillance society; and, finally, the place of spirituality in the modern workplace.

In all, we feel that these sections, and their chapters, encompass a great range of issues that are of critical importance to understanding contemporary Irish business and society. That there is overlap between some of the chapters, despite the fact that their authors come from different disciplinary backgrounds, and in some cases are based outside Ireland, highlights how a modern society is a highly complex and integrated entity. Thus, issues of political concern are also of economic and social concern, and vice versa, highlighting the value of an interdisciplinary volume such as this.

CONCLUSION

In compiling this volume, our aim has been to fill a gap that has existed too long in Irish academia, drawing together, as it does, business and social science research to provide a multi-dimensional set of perspectives on our country at the start of a new century filled with opportunities and challenges. Although there are a range of business, economics, sociology and politics texts that look at Ireland, none is as broadly interdisciplinary as this. The absence of a volume such as this has meant that some third-level courses on business and society have been taught using either British or US texts. While those books are fine, and present the reader with a comprehensive understanding of contemporary issues in British or US business and society, they are not ideal for an Irish audience. Although Ireland is a western liberal democracy, like Britain and the US, the fact remains that it is also different from both of those countries for a host of reasons. Such differences can only be fully addressed through a dedicated volume. Thus, we have produced this book to provide the reader with a critical analysis of what is currently taking place at the nexus of a variety of aspects of business and society in Ireland.

The chapters in this book are grouped into related sections, but each contribution is also a self-contained unit. In this way, readers can, by examining just one chapter, gain an insight into a contemporary issue in Irish society. The general reader can dip into the book, while the student or academic is provided with the opportunity to familiarise themselves with a more comprehensive understanding of the broader issues at play.

Of course, none of these chapters are presented totally value-free, devoid of a wider impact. The nature of each chapter – its structure, arguments and point of view – is influenced by the perspective of its author or authors. Thus, certain chapters are written from a left-leaning perspective, while others come from the right of the political spectrum. This will provide for a more balanced appreciation of the issues set out, while also offering insights into how perspective influences understanding of a topic. Our hope is that readers from across a range of backgrounds, political persuasions and interests will find this a useful volume in assisting them to gain a more comprehensive understanding of Irish business and society. In summation, our intention is not to be prescriptive and, while contributors point to the implications and possible solutions to the issues raised in their chapters, there is space to re-imagine our past and present into a qualitatively different, and potentially better, future.

References

Allen, K. (2009) Ireland’s Economic Crash: A Radical Agenda for Change. Dublin: Liffey Press.

BBC News (2010) ‘Davos 2010: Sarkozy Calls for Revamp of Capitalism’, 27 January [online]. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8483896.stm (last accessed 6 February 2010).

Cadbury, A. (1987) ‘Ethical Managers Make Their Own Rules’, Harvard Business Review September–October: 69–73.

Cooper, M. (2009) Who Really Runs Ireland? The Story of the Elite Who Led Ireland from Bust to Boom . . . and Back Again. Dublin: Penguin Ireland.

Edelman (2010) Edelman Trust Barometer 2010 Irish Results [online]. Available: http://www.edelman.ie/index.php/insights/trust-barometer/ (last accessed 6 February 2010).

Haughton, J. (2008) ‘Growth in Output and Living Standards’, in J.W. O’Hagan and C. Newman (eds) The Economy of Ireland: National and Sectoral Policy Issues, 10th edn, pp. 145–73. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Kinsley, M. (ed.) (2008) Creative Capitalism: A Conversation with Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and Other Economic Leaders. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

O’Hagan, J.W. and Newman, C. (eds) (2008) The Economy of Ireland: National and Sectoral Policy Issues, 10th edn. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

O’Toole, F. (2009) Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger. London: Faber and Faber.

Reich, R.B. (2008) Supercapitalism: The Battle for Democracy in an Age of Big Business. Thriplow: Icon Books.

Reinhart, C.M. and Rogoff, K. (2009) This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rutland, P. (1994) The Politics of Economic Stagnation in the Soviet Union: The Role of Local Party Organs in Economic Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. (2009) The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane.

Share, P., Tovey, H. and Corcoran, M.P. (2007) A Sociology of Ireland, 3rd edn. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Stiglitz, J. (2010) Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York, NY: WW Norton.

Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, K. (2009) The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane.

World Bank (2010) Doing Business 2010: Reforming Through Difficult Times, Washington DC [online]. Available: http://www.doingbusiness.org/documents/fullreport/2010/DB10-full-report.pdf (last accessed 6 February 2010).

Section I

![]()

The Making and Unmaking of the Celtic Tiger

The chapters comprising this section look at a number of areas of relevance to the making and unmaking of a period that has become ubiquitously known as the Celtic Tiger: changes in the labour force over the past twenty years; the power of vested interests in Irish politics and the process of economic policy making; the emergence and evolution of the Industrial Development Authority (IDA); the enterprise discourse that has dominated how we talk and think about business and its relationship with society; the politics of welfare in Ireland; and the failures of the Irish economic experiment and some possible remedies to bring about change. Chapter 1, by Nicola Timoney, looks at labour and employment in Ireland in the era of the Celtic Tiger. Seeing the outstanding feature of this era as the expansion of the labour force, the chapter provides an overview of key developments in the Irish labour market over the period 1988 to 2008. It examines the size and composition of the labour force, considers the rewards to labour by way of the minimum wage, the distribution of income, and the issue of internationalisation and competitiveness of labour costs, and explores the experience of social partnership. The chapter closes by discussing some of the major challenges facing the labour market in the near future.

Moving to Chapter 2, which deals with the political economy of policy making in Ireland, Frank Barry argues that the power of vested interests and the particular characteristics of democratic electoral systems frequently lead to policy decisions that operate against the interests of society as a whole. The chapter examines decision making in some of the now widely acknowledged policy errors of the boom period. However, this chapter also considers how ‘political cover’ has enabled a number of beneficial historical policy changes to be achieved. This analysis provides some suggestions as to how decision-making processes might be reformed to secure more advantageous outcomes in the future.

In Chapter 3, Paul F. Donnelly traces the evolution of the IDA through the lens of path dependence theory. The story charts the IDA’s creation within protectionism in 1949 and its subsequent evolution in an environment of free trade. The chapter follows the IDA’s emergence as the state’s pre-eminent industrial development agency, its re-creation as a state-sponsored organisation and the growing political, institutional and monetary resources afforded it in return for delivery on objectives. However, the increasing reliance on foreign investment to meet targets, at the expense of indigenous industry, eventually surfaces as a challenge in the early 1980s and culminates in the IDA being split into separate agencies in 1994.

Another important element of process in policy making is the language a society uses for talking about business, and Chapter 4 examines how this both facilitates and constrains how business is done. Brendan K. O’Rourke describes and analyses a dominant way of talking and thinking about business, called ‘enterprise discourse’. This form of business discourse relies heavily on seeing all organisations as best when following the mythology of how it is imagined that small, but fast-growing, private enterprises are run. An understanding of enterprise discourse, its features and a sense of it as a discourse dependent on the historical circumstance in which it emerged is useful.

Mary P. Murphy, in Chapter 5, looks at the politics of Irish social security policy over the period 1986 to 2006. Offering a case study of the Irish social welfare policy community, and curious about why the Irish social welfare system has developed in a different direction from that of other English-speaking countries, the chapter asks whether a relative absence of Irish social welfare reform can be explained by examining the politics of welfare. ‘Policy architecture’ is offered as a way of framing an examination of how the general Irish political institutional features interact with the institutions and interests of the Irish social welfare policy community.

Finally, pondering whether the Irish economic experiment is doomed to fail, in Chapter 6 Bill Kingston begins by arguing that the global banking disaster has hurt Ireland more severely than other developed countries because, from the foundation of the state, government intervention progressively became the characteristic way of running the country. Seeing the crisis as delivering proof that intervention does not work, allied with the vagaries of an electoral system that results in constrained and weak governments and a civil service that cannot be held accountable for what it does, or fails to do, the chapter makes a case for dismantling much of the state apparatus supporting, and puts forward some interesting alternatives to, intervention.

Chapter 1

Labour and Employment in Ireland in the Era of the Celtic Tiger

INTRODUCTION

This chapter examines the changes and key developments in the labour market in Ireland over the twenty-year period from 1988 to 2008. The Celtic Tiger was first and foremost an era of strong economic growth at national and per capita levels. But the increase to unprecedented levels in the numbers at work in Ireland was probably the greatest achievement of the period. Improvement in the employment situation was the aspect of economic growth that most directly affected the lives of people in the country.

The first section of this chapter provides an outline of what happened in terms of the labour force increasing with the overall population. Participation rates – percentage of those in an age group actually seeking work – increased. Numbers actually at work increased to over two million for the first time in the history of Ireland. The sectoral pattern of this employment is then examined.

In the second section, the ‘rewards’ to labour are examined. First, a specific policy initiative affecting rewards to labour – a minimum wage – was introduced in 2000. The pattern of distribution of earnings is then briefly reviewed, together with available data on income distribution. A trend towards internationalisation of the labour force has been present for some time, since net migration became positive from 1995 onwards. Some evidence on the effects of this internationalisation has become available. Drawing together the developments affecting rewards to labour, the effects on competitiveness of labour for a small open economy such as Ireland are considered. The evidence suggests an initial improvement in wage competitiveness, especially in relation to manufacturing, in the 1990s.

The third section of the chapter investigates the role of social partnership in these developments before considering the current challenges. The great improvement in the labour market, as expressed in the dramatic reduction in unemployment, and the outstanding performance in terms of economic growth, coincided, at the very least, with the experience of social partnership. A new form of social partnership (from 1987) preceded the boom: another renewal in Irish neo-corporatism is required now, as a response to the current crisis.

OUTLINE OF THE LABOUR FORCE

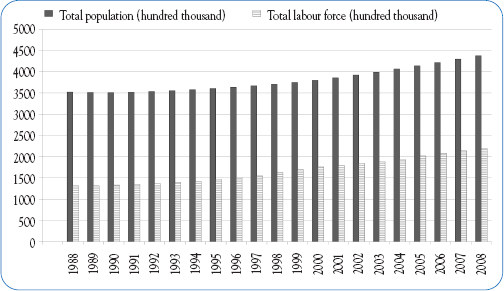

Figure 1.1 shows how, in the twenty years from 1988 to 2008, the overall population of Ireland increased by approximately a quarter, while the labour force increased by two-thirds.

Figure 1.1 Total population and labour force (aged 15 and over), 1988–2008

Source: derived from ILO (2009a) © data.

The labour force – defined here as persons aged 15 and over who are economically active – increased from 1.3 million persons in 1988 to 1.6 million in 1998, and to 2.2 million in 2008. Following Hastings, Sheehan and Yeates (2007:75), we may define the period 1997 to 2007 as the ‘Eye of the Tiger’, although precise timings may differ. We see here that the increase in the size of the labour force – those at work or seeking work – is particularly evident over those years, rising from to almost 1.6 million in 1997 to 2.1 million in 2007. The labour force increased by 38 per cent over those ten years, while the population increase was close to 17 per cent.

Changes in Labour Force Participation in Ireland: Male and Female

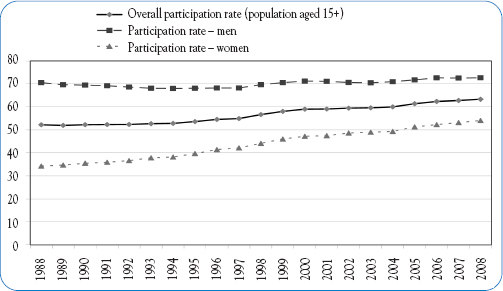

The overall participation rate is the percentage of the population over 15 years that is seeking a job. There had been a steady rise in the Irish participation rate from 1988, when participation of the adult population in the labour force was 52 per cent, as shown in Table 1.1. By 2008, participation had reached 62 per cent. Comparing Ireland internationally, using data from the International Labour Organisation (2009b), we see that Ireland’s overall participation rate is now close to the world average. Distinguishing male participation and female participation, Ireland’s rate of male participation has been, and remains, a little lower than the world average. The trend for male participation is downwards for the world average, but somewhat upwards for Ireland in recent years. For women, the participation rate in Ireland changed from being below the world average in 1998 to equalling it in 2008. There are thus noticeable differences in the pattern of male and female participation for Ireland, within the context of an overall increase in participation.

Table 1.1 Comparative labour force participation rates (age 15+) in percentage

| 1988 | 1998 | 2008 | |

| World – overall participation | 64 | 63 | 63 |

| Ireland – overall participation | 52 | 55 | 62 |

| World – male participation | 79 | 76 | 74 |

| Ireland – male participation | 71 | 68 | 72 |

| World – female participation | 49 | 49 | 52 |

| Ireland – female participation | 34 | 42 | 52 |

Source: derived from ILO (2009b) © data.

Figure 1.2 Participation in the labour force: rates for men and women, 1988–2008

Source: derived from ILO (2009a) © data.

Figure 1.2 gives a fuller picture of the trends in participation in Ireland from 1988 to 2008. There is little variation in the participation rate of men over the twenty years, while changes in the participation of women are more marked.

The numbers at work – persons employed – is a central aspect of the country’s economic progress over the past twenty years. In Ireland, the numbers at work increased more than either the total population or the population aged 15 and over.

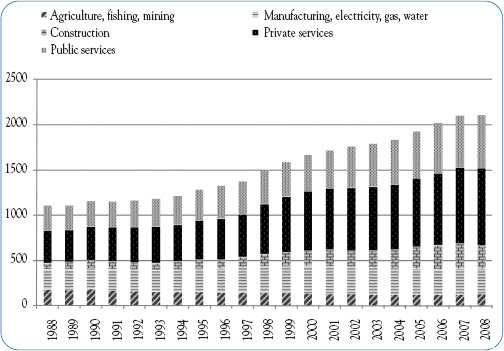

As the height of the bars in Figure 1.3 shows, the total number at work increased from 1.1 million in 1988, to almost 1.5 million in 1998, and reached 2.1 million in 2008. This near doubling of the numbers at work is the most striking feature of the labour market experience in Ireland over the twenty-year spell: again, the increase over the years 1997 to 2007 was particularly strong.

Changes in the Sectoral Composition of the Workforce

In addition to the changes in the numbers of persons at work overall, there have been changes in the sectoral composition of the workforce, that is, in the economic sector or industry in which people work. Changes in occupations are not considered here (see O’Connell and Russell 2008); rather, consideration is given to sectoral changes that have taken place from 1988 to 2008, as illustrated in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Employment by sectoral classification, 1988–2008

Source: derived from ILO (2009c) © data.

Figure 1.31