Copyright 2014 by Rich King and Lindsay Eanet

Publishing History

Trade paperback edition - September 2014

Published in the Unites States by

Eckhartz Press

Chicago, Illinois

All Rights Reserved

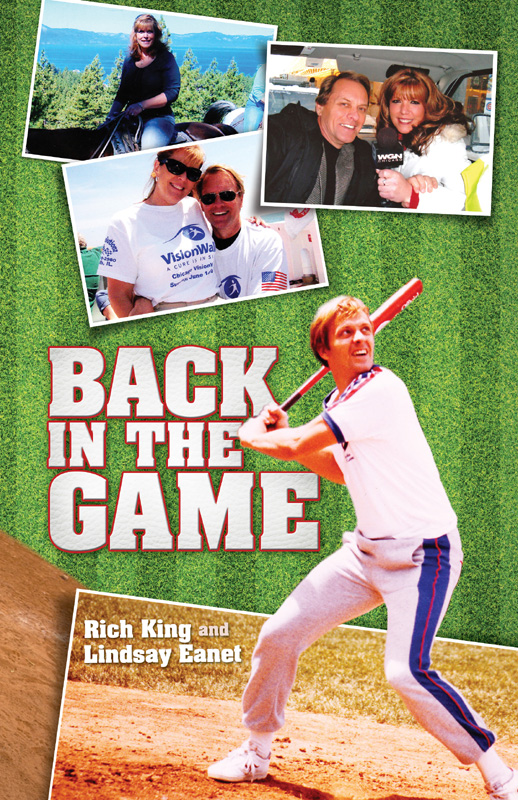

Cover and interior design by Vasil Nazar

All photos from April and Rich King’s personal collection

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

eISBN: 978-0-9904868-4-8

v1.0

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Page

Praise

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Afterword

Acknowledgements

About Authors

Publisher Page

PRAISE FOR BACK IN THE GAME

“I breezed through the pages not only engrossed in the phoenix of Rich’s “second” life with his new bride, but thoroughly enjoyed traversing with him through his memorable career. A truly good man who thankfully for all of us chose to tell another good story about his remarkable life.”

-Mark Suppelsa

WGN-TV News

“If Rich King’s first book, My Maggie, tugged at your heart, Back in the Game will warm your spirit. What an uplifting book! It’s not just a story of renewed hope, Rich also manages to weave in stories about his 40-year Chicago broadcasting career. A must read for Chicagoans.”

-Jerry Reinsdorf

Owner Chicago White Sox, Chicago Bulls

“Kudos to veteran sportscaster Rich King for sharing his experience of love, loss, and learning to love again. Mr. King is admirably open in describing his journey from despair to hope, and he has much to teach about the importance of relationships in living a vigorous and fulfilling life. On top of that, he provides us with an enormously entertaining account of sports journalism that should delight any Chicago sports fan.”

-Neal Spira, MD

Dean

Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis

Dedication

For April who gave me new hope and life

BACK IN THE GAME

Prologue

No one ever expects to sit on a couch talking to a psychotherapist. It’s an almost out-of-body experience. As a guy who was raised by a hard-nosed father who expected you to shoulder responsibility without complaint, I especially didn’t.

But there I sat, at the advice of my internist, in the office of Christine Jacobek. Poor Christine. She had to endure my endless rants about the unfairness of life. I unleashed the repressed anger that boiled inside in torrents in her office, a flurry of balled-up, shaking fists and red-faced frothing at the mouth. It all stemmed, of course, from the loss of my first wife, Maggie. The anger stage in the Kübler-Ross model for grief was, for me, quite extensive.

My relationship with Maggie thrived, evolving from childhood sweethearts to a thirty-two year marriage. I also became her chief caretaker for the final fifteen years of her life, a role I loved. She had battled past major obstacles to live the sweetest of lives. A rare progressive disease that was robbing her of sight and sound, three different cancers and an uphill battle out of a poor inner-city neighborhood did not stop her. She died at the age of fifty-three, and it made me angry, very angry. Christine caught the worst of it.

I detailed all of the feelings I had back then in the book I wrote, My Maggie, which was published in 2007. A brief explanation of that book may be necessary before beginning Back in the Game. I had written to preserve her memory and honor her, to help me grieve, and to help others who had lost a spouse to a devastating illness heal.

The process of writing and promoting that book nearly killed me—literally. Before the final stretch of the book tour, I found myself in the hospital on the verge of a massive heart attack. I let self-pity take over, which fed into a crippling depression. As I was trying to help others heal, I was living my life in direct opposition to what Maggie stood for and what I had outlined with great passion in the book. She would have despised my conduct in Christine’s office. She would have despised my way of life, resigning myself to this burned-out, lonely, self-pitying bachelor lifestyle.

Near the end of My Maggie, I explained what she meant to me:

Maggie and I were crazy in love. It was not just some romantic notion. It was the real thing that transcended the physical world. How else could I describe what happened? She was an awkward tomboy with hearing aid wires tangled in her dress at the play lot in that now distant innocence of our youth in the 1950s. I was there. She was a blossoming beauty in her teens with that gorgeous long flowing blonde hair. I was there. I was there in Wauconda seeing the breathtaking eternal love in her eyes. I was her soul mate for all the happiness that filled our lives as husband and wife. I was with her for all the hard work, the exotic vacations, the zany antics and the great friends. I was there throughout the bad times—the hearing loss, the blindness and the cancers. It was enormous adversity that we did not let break us, but instead used to bind us even tighter. I was there for all of it. Nobody else had as much of her. Yes, there should have been more- but I can hear her telling me softly now:

“But, Richie, there wasn’t.”

Our magical time was cut short, for sure. What Maggie gave me was so powerful, I could no longer feel cheated.

That last line I wrote turned out to be a complete lie. “Look, you don’t understand,” I told Christine. “I am happy in the past. Maggie is there. I can be with her there. She is not here now. In the present, I’m alone.” I scoffed at any meaningful future with another woman, laughed bitterly about the insanity of another marriage.

Some people told me that seeing a therapist was a waste of time. Most of this advice came from men, which I fully understood. But, in retrospect, seeing Christine was a huge help. Besides allowing me to vent, she offered some gentle guidance. When I said I would never get married again, we got involved in a battle of semantics. “You can say never,” I pointed out. “I said I would never leave Maggie and never did. If you get bad food at a restaurant, you never go back.” What I was really saying is that I would never recover from losing Maggie. Christine was trying to guide me out of my malaise. I realize now, I was running away from what I could not deal with. When Maggie was alive I had some degree of control over her well-being. When she died, I was left feeling weak and depleted. Intellectually, I wanted to move on. Emotionally, it was impossible at the time.

On the inside, I was one sorry, sad sack of a guy. On the outside, I was able to fake it, as countless others have done before, maybe even you. Comedians, priests, even psychiatrists can be depressed. Just days before this book went to press, Robin Williams tragically took his own life. Sportscasters can act as if they are enjoying every minute on the air. But when you are alone, the empty feeling returns and stays with you until you begin to fake it all over again.

Maggie died in 2002. My Maggie was written in 2004 and published in 2007. If you encounter this book having read its predecessor, you know she was my reason for living. Caring for her and giving her the best quality of life in those final years became a second-full time job; more than that, it became my livelihood, my purpose. And when she was gone, I had become something of a professional mourner. Grief must be endured, and the time of that pain depends on the individual. In my case, the deep pain lingered for six years and might have gone on but for one long shot date with one special woman that changed my life.

It was our friend and attorney, Anna Morrison-Ricordati, who recommended I write a book about my experiences after Maggie died. “You may be able to help a great number of baby boomers who are experiencing that same loss,” she said. I hated writing about myself but kept going, and thanks to the help of Lindsay Eanet, the book was completed.

When you reach the advanced years of life, you begin to think you have a handle on things. Not so. I was adamant I would never get married again. I did. I have threatened to retire from my job more times than Brett Favre. I am still working. I wrote a book about a courageous woman then acted cowardly. I now know I have a handle on nothing in life. The serious side of this book, the battle against depression, is simply my own story. It is not meant as any lesson or measuring stick on grief or how to fight depression. If anyone benefits from what happened to me, I would be extremely pleased. But if the book results in merely an exercise in empathy for others who have battled depression, that would also be enough for me. It does sometimes help to hear or read about others who are in a similar situation.

There is also a not-so-serious side of the book. After four decades in broadcasting, my career days are numbered. It has been an amazing ride. Wherever I go people seem to love inside stories about sports personalities. Rather than write a memoir, this provided me with a chance to just relate some stories about the great personalities I have met in forty-six years in the radio and television business, icons like Jack Brickhouse, Brent Musburger, Lou Boudreau, Walter Payton, Michael Jordan, Bill Veeck, Jerry Reinsdorf, Harry Caray, Johnny Morris, Mike Ditka, Brian Urlacher Brad Palmer, Doug Buffone, Tom Skilling and Dan Roan, among others. I have had the pleasure of dealing with a lot of sports and broadcast Hall-of-Famers. I could not resist spinning a few yarns.

Coming from a working-class neighborhood on the South Side, Pilsen, the odds against such a career were enormous. I am grateful to all those who listened to me and watched me over the years. I am Chicago’s very own, born at Holy Cross Hospital, schooled at St. Procopius, De La Salle, and UIC. I am one of you.

Chapter One

In the years after my first wife’s passing, I came close to dying twice. The first near-death incident happened one snowy night on a mountain in Pittsburgh.

I was covering a Bears game for WGN-TV. As the Steelers’ pile driver Jerome “The Bus” Bettis began to take over the second half, the sky grew greyer and more ominous. It snowed harder. The sky grew dark. Even a few diehard fans, no strangers to this weather but sensing both a blowout and an icy trip home, began to leave their seats. A trickle of black and gold began to flow through the stadium doors. The PA announcer came on, imploring everyone to drive safe. We were safe from the elements up in the booth, but we still had a long evening ahead of us.

My postgame objective was clear—Dan Leister, the station Operations Manager, had set up a postgame tape feed from a nearby TV station. We had to get the highlight footage and postgame sound bites to the station for the sportscast that evening. “It’s only two miles from the park,” he said. Two miles. No big deal.

What he forgot to mention was that it was two miles straight up a steep mountain.

The directions he gave us were two pages long. Every line represented a turn, the mountain curling and rising like a spiral staircase. Moments into the drive, my cameraman and road partner, Richard “Ike” Isaac, began having trouble behind the wheel. We tried not to think about the potential hazards of this journey. He kept a death stare on the road; I shuffled through the complicated directions. We felt the tires begin to skid and slip ever so slightly, but Ike would find a way to regain control. We would drive a few feet, slip again and then recover. Every time the car would slip, we both held our breath for a second. Ike, a normally funny and upbeat guy, was quiet, gripping the steering wheel, deep in focus. All we could hear was the car’s groaning motor and the splatter of snow on the windshield.

The road was an ice rink. A few of the locals came rushing out of their homes to warn us as we trudged forward. It was like something out of a horror film, the warnings of “Don’t go up there! You’ll never make it!”

We had no choice. The “do or die” feeling took over. We had to feed the tape for our viewers back in Chicago or we would be fired. About halfway up, I turned my head and saw Ike’s face for the first time. He was wide-eyed and white-knuckled, with a twinge of green in his face. This was a look of sheer, sickening panic. Then, I realized why. The car stalled and began to slide backwards down an icy street.

“What the hell are you doing?” I shouted. “I have no control,” he shouted back. The car was skidding straight down, heading for a small barrier. That thin piece of guardrail was the last thing between our car and a mile-long plunge into the icy abyss. If we crashed through it, we were done. The snow was still pounding down. This is it, I thought. We’re done. We are going to die up here. And there’s no chance of us getting the tape fed. I shut my eyes and prepared for the free-fall.

As we were sliding backwards, my life for the past several years began to flash before my eyes. Since losing Maggie in 2002, I had been locked in a perpetual state of self-pity and a sense of let’s-get-it-over-with. I didn’t want to give up on life completely, but my life didn’t feel like anything worth preserving. Maybe if we did go over the abyss, I would at least be reunited with Maggie. I would feel, maybe, somewhat complete again.

Luckily for us, we did not slide to an icy, violent demise. The car veered off to the left and plowed into the fence in front of a house. We breathed a sigh of relief on impact. Nobody was home, so we left a note with our phone numbers and took off again. “This is not going to work,” Ike said.

While shaking off the shock of our near-death experience, I got the idea to call the station at the top of the hill so they could send down a heavier truck to bring us up. They obliged, and down came two young kids in a station van.

The ordeal was far from over. At this point, the sky had long been dark, yet we were in a whiteout. The windshield wipers churned at top speed against the curtain of snow. We could barely see in front of us. As we seemed to drive around in circles, I began to get suspicious.

“Are you guys lost?” I asked.

“Oh no,” they said, “We’ll find the right road.”

After a few more turns, I asked the driver to stop the van so we could get a better look at things. The car had stopped about a hundred feet from another small barrier that protected another mile or more drop into the river. I could see some lights at the bottom of the mountain. My stomach knotted itself even tighter now. We had been heading right off the cliff for the second time in a half hour. We had almost plummeted to our death twice now.

Eventually, the kids got us to the station where we had scant time to prepare our tape package. By then, the acid had pretty much eaten away the lining of my stomach. But, we did it. Mission accomplished.

When we got back to the hotel, we ran into Mark Malone, the former Steelers quarterback who was the chief sports anchor at Channel 2 in Chicago.

“You guys are lucky you’re alive,” he laughed, “The only way to get up to that station on a night like this is in a snow plow.” Ike and I sat at the bar and downed a few cocktails to settle our nerves.

“You know something,” I told him, “If we had gone off that cliff, the last thing I would have told you in our final seconds of life would have been that when we land, we have to figure out a way to get this tape fed.”

Chapter Two

The same dream haunted me nearly every night for two years. I would be sitting in my condo, across the kitchen table, talking to Maggie, or in bed, and I would look over and see her. She would be there, alive and well and talking to me. And I would be talking to her, as if nothing had happened. And then, all of the sudden, I would snap. “Wait a minute,” I’d say suddenly. “This can’t be happening. I can’t be talking to you. You’re dead.” And she wouldn’t reply. I would start grappling for answers, and she would be silent. Then I would wake up.

One time, early on in this series of haunted sleeps, I woke up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom. For the first twenty seconds of being awake, I thought—no, I was convinced—that Maggie was still there. I thought she was lying in bed right next to me, and for those twenty seconds, I was completely relaxed. I was happy. I was totally conscious and happy. But when the empty side of the bed appeared and I realized she was still gone, the gloom engulfed me again. It was all so surreal. I swore she was there, and the absence stung even more.

In the first two years after Maggie’s passing, the pain was a ripping, unrelenting constant. I battled panic attacks on the air. Every time an old song came on the radio that reminded me of her or we passed an old building we had visited together—the site of a date, a friend’s apartment, something of significance in the old neighborhood—I fended off shuddering crying spells. If it happened at a party, I would retreat to the bathroom and try to regain composure. A few deep breaths and a splash of water on the face later, I returned to the party and prayed no one would notice how red my eyes had gotten.

The worst came while listening to Carly Simon’s version of “Danny Boy,” already a song so full of sentimentality, heavy with sadness. Maggie was the epitome of South Side Irish to the core, and that old Irish tearjerker did me in. I was so overcome with emotion that I had to pull over. I sat in my car, on the shoulder of the Kennedy, sobbing into the steering wheel. I felt as though I was coming apart.

I felt like I had to hide this from everyone. I hid these feelings from friends, coworkers and especially the women I dated in the year’s following Maggie’s death. Internalizing this pain was exhausting, but I felt some sort of obligation to keep it to myself, to own it and not force it on others. I have spoken with other people, men especially, who have lost a spouse and have felt this same incessant need to repress the pain. As I learned the hard way, denying yourself permission to feel and work through the extreme emotions can throw a wrench into the healing process. When you try to suppress emotion like that, or hide it from others, it ends up dulling and turning into anxiety or depression.

And that’s precisely what happened to me. Eventually, the extreme, almost tangible pain dulled into a quiet but constant depression. I learned how to repress the depression, too, for the people in my life. I put on a brave front when I was on the air, ever the grinning news personality, bantering with my coworkers for the camera. I am a much happier person now than I was then, but every once in a while, the pain comes back. A song will come on, like it did for my crying fit on the Kennedy, or a thought will pop into my head or I will visit one of our old neighborhood haunts, and I will think of Maggie and the longing will return. This is the thing about the loss of a loved one—even if you go on, it still hurts every now and then. There is no time limit on the grieving process. For some people it takes a few months; for others, it could be half a lifetime.

I don’t want to give the impression that I was on an island in my misery after Maggie died. Even as I internalized the pain, my family and friends stood by me. They gave me unwavering, openhearted support.

My college friends, the old Hinsdale “Rat Pack,” were still a huge part of my life. Jim Benes and his wife, Andrea Wiley, consistently offered their help in every way possible. Lifelong friendships are very special and even though I no longer lived in Hinsdale, we still remained close.

Then there was Ron Gorski, who called me almost every day in Maggie’s final weeks. “What do you need?” he would ask, eager to jump at any request. “What can I do?” At a time when I had lost the person who had not just been my better half, but truly half of my whole being, I was beginning to feel the isolation and loneliness striking through the initial shock and grief. Having a great support network of friends, especially guys like Ron, during those first few months may have been the only thing keeping me going.

At Maggie’s memorial service, I asked Ron to be my backup if I could not make it through my final tribute. I gave him my notes in quaking fingers. I didn’t want to part with it but knew he could be trusted. “Here it is,” I told him. “Can you read it?” I thrust the papers into his hands. He looked at me with the dutifulness of a soldier.

“No problem,” he said. An hour before the service, we had to test the TV circuit for the video history WGN cameraman Steve Scheuer and I had put together. I had selected Maggie’s favorite movie score, the beautifully sad theme to the movie, Somewhere In Time.

Ron was in the back of the church when the music began. As soon as the first few strains lifted, I heard a cracking voice, like a violin strung too tightly. Then, the closing of a door. It was Ron. He had broken down in tears three bars into the song! He had to rush out to the back door before he began crying. My backup was a wreck! As emotionally charged and tragic as that day was, I think back on it and feel a great love for my close friends. Through the years, we all had each other’s backs.

I also had my mother, who had been my sole responsibility since my brother, Don, passed away in 1994. As she advanced beyond ninety years of age, every day I had her became more precious. As I write this, she is now ninety-six and still going relatively strong. Her biggest complaint is all the traveling I do.

“I hate those damn airplanes,” she tells me constantly. “Why don’t you just stay home?” After Maggie died, she called constantly to check in. She brought me boxes of dry snacks—granola bars, cereal—to make sure I was still feeding myself in my state of grief. Even at sixty-one, I still found myself needing my mom to take care of me every now and then. You might, too.

Despite this support, however, the emptiness that engulfed me after Maggie died simply would not go away. It is sobering to look back and remember the horribly depressing things that came out of my mouth in Christine’s office. A minor in history at UIC, a voracious reading habit and a background as a newsman turned me into a current events freak. I felt there was only doom for mankind. I was born in the shadows of World War II, grew up during Korea and Vietnam and witnessed frequent incursions into South America and the Middle East.

“Hell, we have been a country at war on a regular basis.” I told her. “Someday soon it really is all going to blow up.” It almost did during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. In short, I felt the whole world sucked.

“Good people get crushed.” I asked her, “Do you think it’s a coincidence that JFK, Bobby and Martin Luther King were all assassinated?”

I fully believed that all three killings were a conspiracy, despite evidence to the contrary, at least on two of them. “I’m done with it all,” I continued, “I just want to live the rest of my life enjoying golf and they can burn me and toss the ashes in the gutter.”

As for Maggie, I said, “One hundred years from now nobody will be around to know that she did, what she accomplished and how many people she helped. Think about graveyards. Who visits the tombstones of men and women who died two centuries ago? It’s all totally meaningless.” Almost every week was an exercise in sarcasm and bitterness. It seemed nobody had it as bad as I did.

But then, when I walked out the door of her office, the façade returned. What’s weird is that the façade actually saved me in a way. Working, dating and the routine of everyday life forced me to be the person I was before Maggie died. It was the person I wanted to be again but could not inside my heart or inside Christine’s office. The only word I can used to describe this inner feeling is emptiness.

Eventually, I just got tired of being sad all the time. I began dating again. I dated all kinds of women. I dated for six years. Along the way, there were many wonderful experiences. The less-than-stellar moments were mostly my fault. I pretended to not care about commitment while treating the women I dated as though we were already fully committed. I sent many mixed signals. I realize now that this was incredibly unfair.

I acted like this for a number of reasons. One was that marriage was all I knew for decades—I had only really ever been with Maggie, and we married young. I grew into these habits and assumed that this was how I was supposed to treat all women. The other reason was that I was weary of small talk. I could not sit there for another evening at Volare or Gibson’s or some new Streeterville cocktail bar, watching the bubbles rise in my vodka tonic while pretending to be engaged in my date’s story about her years at Indiana University or her interest in botany or her cats. I know this is unfair, and my disinterest made me feel gross. Like I was some sad, lecherous old man who did not care about anyone else’s feelings and just burrowed into my own sadness. I knew it wasn’t fair to my dates. It embarrasses me even to write about it, but I do so hoping that others who seek to date after the loss of a longtime partner learn from my mistakes. Please be gentle to yourself and others. Be honest about what you need and want in that time. It will make things easier for you and your dates.

I wanted to date. Christine also felt that dating would be a big step forward in my bout with depression. I wanted just to be busy, to focus on anything other than my thoughts. But I hated the small talk. I hated the idea of having to start over when everything had been so natural and comfortable for decades. The act of small talk, even, made me miss Maggie more; miss the ease of our pillow talk and the liveliness, the crackling strings of language, that she brought to every conversation, no matter what we were talking about.

When you are emotionally drained, you lose the taste for starting over. The time was closing in on the dating charade for good. I was about to accept the life of a widower, when my friends and loved ones convinced me to give it one more go. For whatever reason, I agreed.

The latest episode of my shambolic dating life was about to take place at my favorite downtown restaurant, Volare. As I walked toward the revolving doors, the expectations were low for a luncheon with April, a long-time friend of my friend, Joel Bierig. If not for his perseverance, I probably would have given up on the date ever happening. I had April’s phone number on my “to-do list” for two full years.

“You’re making a big mistake.” This was Joel’s mantra for two summers. Every drive to the next hole in the golf cart we shared, every new round at the clubhouse, was a new opportunity to talk up his friend. “She is a fantastic girl, great looking, intelligent. You need a younger woman in your life. Give her a call.”