COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL

© 2014 copyright by Elizabeth Earley

First ebook edition. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-937543-49-5

Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information please email: questions@jadedibisproductions.com

Published by Jaded Ibis Press, sustainable literature by digital means™ An imprint of Jaded Ibis Productions, LLC, Seattle, WA USA

Cover and interior art by Christa Donner.

This book is available in multiple editions and formats. Visit our website for more information. jadedibisproductions.com

For Katy

There’s a buried town in Italy where a thick layer of volcanic ash and stone fell in the first century, AD. Pompeii was buried so quickly and hotly that, when excavated hundreds of years later, a single moment in time was found perfectly preserved. People with upturned heads, busy hands, embracing arms–even vivid facial expressions–were preserved in situ. And so it is with me.

When a seemingly senseless tragedy descends upon a family in an instant, that point in time becomes the preserving link that binds them together ever after, even in their scatterings. It leads to the establishment of unintended hurdles and blocks, false dead-ends from which it can be impossible to extract oneself. The tragedy thrusts its reference onto every moment to follow, colors everything, shapes everything. Through everything it becomes less a tragedy and more an event, one among many, its precedent allowing the materialization of great gifts. The event is an emblem, one that must be overcome, not through rash force but rather through transformative realization.

The emblem serves as a meditation, a kind of practice for believing it will all be–we will all be–it is, already, all–okay.

Her eyes still bulge. Twenty years later they bulge, as though the pressure from her swollen brain has pressed and pressed ceaselessly like time on a life, never letting up. They used to be blue–a big, watery blue that fixed on me and shimmered. Now they are gray and bulging like the sky pregnant with rain, gloomy and beautiful. I remember them being that bold, young blue, but that doesn’t mean it’s true. I was a child then, too young to see things for what they were.

She was a child too, but an older, more complicated kind: a teenager. We shared a bedroom and talked about everything. More accurately, she talked and I listened. June was always telling stories. She was gifted, exceptionally smart, an honor student, the model of responsibility and goodness. I knew her inner world, though, the one that concealed tall, brightly-lit desires. I knew she thought of going all the way with her boyfriend, Travis. She explained what it felt like to let him kiss her, to let his hands press against her small breasts. She told me that when he pinched her nipples, it gave her a sick feeling in her stomach. When his hands tried to move below her bellybutton, however, she drew the line. The boundary of her waistband was an impassable cliff. At least until she decided she was ready.

Then there was the time she confessed the big thing. We sat on her bed with our limbs folded and heads leaned in toward each other. She lowered her voice to a whisper and said, “I broke into a house last night.” She smiled. Her chrome braces shone. My eyes shot open wide and I chewed on my cuticles.

“It wasn’t my idea,” she said. “We had some beer and some wine coolers my friends snuck from their parents, and we needed a place to drink them. I got drunk for the first time, I think. We ate some of their food like chips and stuff. I feel really bad,” she added, but she didn’t look like she felt bad. She looked pleased, exhilarated even. I just continued to stare at her and tear off bits of skin from around my fingernails with my teeth.

“Stop doing that,” she said and pulled my hand away from my mouth. I held my hand out between us and regarded my raw, bleeding fingertips. She grimaced and sighed. I lowered my hand.

She dropped back onto her elbows. The lazy, easy way she moved suddenly seemed so sensual, sexy even. There was a new sophistication creeping into her familiar face–it came along with the tan she was getting from more frequent trips to the tanning salon. Her hair was cropped at chin level in a wide, puffy cascade of blonde that swept out from the crown of her head like a bell. She looked older without her glasses.

“What happened?” I asked. “Did you get caught?”

“Of course we didn’t get caught, silly. I wouldn’t be sitting here if we did,” she said. She rolled her eyes and looked away.

I couldn’t believe it. My sister, a hardened criminal.

“What did it feel like to get drunk?” I asked, anticipating her answer with bated breath.

“Nothing, really. I guess it didn’t really work. I think I was too scared we’d get caught,” she said and laughed. I laughed too. I had been drunk once when I was eight. I had stolen four beers from the refrigerator, ran out into the woods, and guzzled them all down, one after another. I remembered how the trees came alive then, every branch another hand to high five me. All was bright laughter and cheer. The world softened and turned golden, beckoning me in a new way. It was when I started feeling hungry all the time. Always hungry for more. I didn’t tell June that. I knew that I eventually would. I had all the time in the world.

She flopped back on the bed. I chewed my fingers and considered the implications. More than anything, I was honored to be the keeper of her secrets. Nobody else in the family talked to me, at least not about anything important, so it carried serious weight. That day she talked about other things, but all I could think of was her crime, its seductive naughtiness. I wanted her to talk more about it but she sternly refused. She switched into the lesson-giver then, pointing a finger to my chest and demanding that I not get any crazy ideas. “It’s wrong,” she told me. This only made it more appealing.

At night, June would sometimes sleepwalk. Her eyes would be open and she would appear awake, but she would be different somehow, hollow and absent like a zombie. It was very spooky, and I often had nightmares about it. In the dreams she would pinch me and smile grotesquely, sometimes laugh, as though she were possessed. I would try to scream, “Wake up!” but only a hoarse whisper would come out. Most of the time, we would be knee deep in water or mist almost as thick as water. I must have cried out during those nightmares because when I woke, her face would be looming over me, shushing and soothing me. She had an enormous metal contraption that came from her mouth and wrapped around her head, some kind of industrial retainer that she was supposed to sleep in every night. That, combined with the huge lenses of her glasses, was a terrifying sight to wake up to in the dark, a terrifying sight that was there to comfort me.

A rearranging of bedrooms took place when June and her twin, my brother Jonas, turned sixteen. They received their own rooms while I moved in with my other brother, Mark, just down the hall. June took over our room. I still sat on her bed every night and listened to her stories. She started inserting French-speaking characters into them, as she was becoming fluent in her fourth year of honors French. She started speaking French in my dreams, too, lispy words I didn’t understand but that sounded beautiful. Most of the time, I fell asleep in her bed and would wake from my nightmare of her sleepwalking to her metallic breath and the warm closeness of her body. I would writhe around for a minute in panic, thinking I was still asleep and she was too, certain I felt the dampness of thick, pewter mist licking my ankles.

Four months after her sixteenth birthday, just days before my eleventh, less than a month before she was due to go to Paris with her French class, she took the car out on her own to pick up her paycheck from Horizons Restaurant. It had been raining. The roads might have been slick with oil, she might have been looking somewhere else, reaching for something in the back seat, or just staring out her window at the sky. Nobody knows why she crossed left of center and crashed head-on into another car. She was not wearing her seatbelt. Mom was the only one to see her when they first brought her into the emergency room at Highland Hospital. Mom told me about the red and blue windbreaker, how they were cutting it from June’s body with scissors. The worst was her teeth: They had been ripped, root to tip from her gums, jutting from her mouth in a ragged arc, strung together and held in place by her braces.

We didn’t know if she would live or die, but Mom knew that if she lived, she would want her teeth, so she called June’s orthodontist. He came that day with his assistant. They went into the ICU where she was hooked up to life-giving machines by slender, plastic tubes like veins creeping out of her body. They worked on her teeth, fitting them back in place and twisting the wire from the braces around them in a tight, makeshift bracketing, planting them firmly in the gums where they would take root and heal. The awesome power of living flesh to grow, to patch up, would, combined with time, restore her mouth, whether she would need it again or not. When they left the ICU, the two men were glassy-eyed and silent. I stood back and watched Mom take the hand of the orthodontist and squeeze it. His eyes were watery and red. His mouth opened then clamped shut again. A quick, nearly imperceptible nod was all he managed before walking away.

We all spent the first several days at the hospital–my parents, my brothers, my other sister, and me, all draped over hard chairs and thinly padded couches in the ICU waiting room. Mom didn’t leave once, not even to fetch things from home. People brought everything to her. The farthest she got from June was out on the sidewalk one floor below where she went to smoke cigarettes, a habit she had quit for a while but now shamelessly started again. Her eyes were swollen with nonstop weeping. Her hands shook ceaselessly. There was a darty, panicky edge to all her movements, yet she was simultaneously slow. The slowness was in her eyes those first days and in the slump of her body–half conscious, adrift.

I returned home to go back to school. I entered June’s bedroom on that first night back and held my breath. I closed my eyes and felt her there, just next to me on her bed, smiling and whole. When I opened my eyes, everything was different somehow. It was all fake–a poorly constructed impression of her room like the set of a TV show. I looked at my feet and felt some important part of me fall out through them and stay trapped beneath the floor. I was hollow and cold. My fingertips throbbed. I stared out the window. The sky looked thick with low-hanging ghosts. I had something like a viewable prophesy then, a sense of the future filled with dulling solitude and strange dreams. Its damp certainty was real, I could smell it in the air. That pinching, smiling, phantom of her continued to haunt me, but I was wide awake. I was not sleeping.

It happened like anything tragic happens–around a blind turn, then splat. It’s in the debris of the aftermath where one might puzzle together a complete picture. A tableau of the day: the splintered beginnings of everything being different for everyone, forever.

Jonas – second born

My brother, Jonas (June’s twin), and his girlfriend, Rachel, had spent the entire morning at the hospital. When Rachel miscarried, she didn’t know she was pregnant. Without telling anyone but June, Jonas drove Rachel to the hospital. While she was behind a closed door being checked over, he slouched in the rigid waiting-room chair, blindly flipping through Tiger Beat, YM, Sassy, Bop, picking one up, fanning the pages, tossing it aside and grabbing another. Jonas bit his nails, crossed and uncrossed his ankles, felt a chilly film of sweat tickle the small of his back. His eyes darted around, scanning for anyone who might know him. What would he do? Hide, he thought, hide behind the pages of one of those shit magazines.

There was another guy about his age with black hair and a shimmering nose ring, a woman about the same age as our mom looking back at him with a frown. Jonas looked away, his eyes settling on a bowl of assorted condoms. He was fifteen when he started having sex with Rachel and they always made sure to use a condom, except for one time. Now, here they were.

On the drive home from the clinic, singer Tiffany warbled, “I think we’re alone now…” on the radio. Rachel stared blankly out the window while Jonas drove her powder-blue Buick carefully toward home. He and June had just passed their driver’s exams and it was raining hard. He didn’t have any experience driving in that kind of weather. He tapped his thumbs nervously on the steering wheel and turned off the radio. The drive was much longer on the way back, he thought.

Eventually the rain died down and stopped. Rachel started crying softly. Jonas switched the radio back on, glancing over at her. She was letting the tears streak down her face with no attempt to wipe them away. They converged under her chin and dripped off, disappearing down the front of her shirt. When Jonas’s eyes followed them to the swell of one breast, he looked back at the road and felt guilty for being turned on at a time like this.

He was driving down Lake Avenue, only a mile or two away from home, when he saw a barricade in the road, a crowd of people beyond, a fire truck, a big crane. He squinted and thought he saw a flash of red and black bent metal. He stopped breathing, pulled the car over with a screech, and ran toward the scene.

A pink-haired woman was sitting in the back of one of the police cars, scowling and mumbling about her car, a pink Cadillac, parked off to the left in a driveway, the hood buckled and the front end smashed.

When Jonas saw the Zephyr, he almost passed out. Black spots bled from nowhere and blurred before his eyes. His legs felt spongy. He leaned forward, hands on knees and closed his eyes. Rachel burst into tears and threw her arms around him. His whole body jerked at her touch. He pushed her back and stood up. She looked wounded, but he didn’t care; he couldn’t. On the other side of the busted car, he saw his little brother, Mark, kneeling on the ground, arms outstretched over his head, face against the pavement, as if in a worshipful bow, bawling and shaking. A police officer crouched next to him with one hand on his shoulder.

“I’m so sorry, son, I think she’s gone,” the officer said. Jonas ran, shoved the officer away, and lifted Mark’s skinny, limp body from the concrete, holding him tightly. Both boys shook with sobs while a crowd watched.

Mark – fourth born

Mark ran up High Street to Lake Avenue and headed east. He had been in his room listening to his new Guns N’ Roses cassette when the sirens drowned out the whining high notes of Axl and the screeching guitar solos of Slash. He looked out the window at an entourage of ambulances and fire trucks blurring by. His heart galloped. He had never seen so many at once. There must be a house on fire or a car explosion.

His mind shot to June, who had taken the car a short while before. She had stopped in his room and dangled the keys in front of him, asked if he wanted to come along for the ride, but he had just torn open the clear wrapper from the cassette case. He had to hear every song on Appetite for Destruction before he went anywhere.

Now his chest felt like it was caving in. He threw down the cassette case and took off. It couldn’t be too far. She hadn’t been gone long. He ran hard, driving his long strides forward and pumping his arms.

He had fought with June the night before. She’d found out that he had stolen from the stash of alcohol she was saving for a party and had confronted him. He’d denied it and dismissed her. She’d made fun of his hair, which was frizzy and long, short in the front, feathered on the sides, and long in the back. She’d told him his Adam’s apple was too big and that his ears stuck out. He’d shoved her and she’d fallen back, hitting her spine on the hard edge of the open window. It had knocked the wind out of her and she’d gasped for air. Mark had begged her to forgive him, had admitted to taking some beers, and had promised he would pay her back. So, she had been making peace earlier by having invited him along for a ride.

He put his head down and picked up speed. Squares of concrete slid by, sounding off in beige tones beneath his feet. He could still hear the sirens in the distance. He smelled his own sweat, and it allayed his panicked pace to a steady trot. But when he saw flashing lights in the distance, he broke into a full sprint. Mark shoved through the small crowd that had gathered and leaped over yellow caution tape. He saw the car and stopped, panting. It was crumpled and torn apart, as if a great hand had bore it up, crushed it like a ball of tin foil, and thrown it down. Looming above was a piece of glinting crumpled metal clutched in the fork of a crane-like vehicle that carried the words “Jaws of Life” along its bright yellow body. Someone grabbed Mark’s arm and tried to pull him back behind the line. He thought of Lee; had she gone with June after he’d turned her down? Had she been in that car too? Both Lee and June’s faces flashed before him, smiling, shining. A weak, cracked “no,” escaped him. His strength gone, he was being dragged back, away from the car. A burst of energy came and he viciously ripped himself free, ran to the car, and collapsed on what was left of its ruined hood, his tears pooling in a metal dimple. Birds lined up on the telephone wire above like piano keys. Their chirps resmbled ominous questions buzzing in Mark’s ears: “Lee, Lee, Lee?”

Lee – first born

Lee was changing into old sweats, getting ready to help Mom paint the living room, when the phone rang. She wondered if it was Craig calling again. She wouldn’t take the call. She had visited him last weekend at Rochester Institute of Technology, had driven nearly over an hour to get there and surprise him. Dressed in a red, lacy number under her clothes, a big smile on her face, she knocked on his dorm room door. It swung open, and a cloud of white smoke tumbled out. A bare-chested, red-eyed Craig emerged like a ghost, some topless slut hanging on his back.

“What the fuck?” Lee said, stepping back, waving a hand in front of her face then pulling her shirt over her nose and mouth to screen out the smoke.

“Lee?” Craig said stupidly, stepping toward her, his eyes growing wider with the delayed realization of being caught. Lee looked at his sculpted chest, lean stomach, the familiar trail of dark hair disappearing into the waistband of his blue-checkered boxer shorts. She looked up at the girl, her black eyes squinting.

The slut snaked her tongue in his ear. The dark tip of one white breast brushed against the back of his arm, peeking and bobbing out from behind him. Lee thought she might vomit. She turned and ran. Craig’s voice boomed after her as she pounded open the emergency exit door at the end of the hall and tripped out into the parking lot. An alarm sounded. Lee scrambled to her feet and scurried to her car, choking back tears.

Late the next night, Craig came to our house drunk and when Lee refused to see him, he stood in the front yard and screamed, “I’m sorry!” until my dad called the police. Since then, he’d been calling every day, and every day Lee refused to take the call.

She held still and turned her head toward her bedroom door, anticipating Mom calling her to the phone any second. What she heard instead was a strange kind of moan coming from downstairs, like the low, rumbled mew that our cat Candy made while she was giving birth to a litter. Lee hurried down the stairs two at a time and landed in the living room just as Mom, with a blue splashed red bandana on her head, a blue-soaked paint brush in one hand, and a salt-white face, placed the phone gently in its cradle. Mom wavered and grabbed the plastic-covered chair beside her to stop herself from falling. She dropped the paintbrush on the floor. Lee ran to her side and slipped a steadying arm around her back.

“Mom, who was it? What happened?” Lee tried guiding her to the chair, but she resisted and broke free.

“It was the police. It’s June. She had an accident…” Mom said, stumbling around looking for her car keys. “You should call your father and tell him to come to Highland Hospital. That’s where they’re taking her. Oh god, oh god, shit! Oh god…”

Lee could see Mom’s eyes blur with tears and instinctively they burned in hers, too.

“Keys!” Mom called out, stumbling out of the living room with its plastic-draped furniture pulled away from the walls, its half-blue, half-white trim. “Where are my keys!” she screamed wildly, just as my dad handed them to her.

My dad was silent and fuming. “Damn teenagers,” he said before walking out the door. (Mark and I, the two youngest, have a different father than Lee, June, and Jonas. Their dad left Mom while she was pregnant with June and Jonas, when Lee was just a toddler. Mom met our dad when June and Jonas were infants and she married him eight weeks later.)

Lee watched the maroon minivan pull out of the driveway. She picked up the phone and, with a shaky finger, called her dad. Her press-on nail hooked into the 9-hole and scraped along the circle all the way to the top. It felt like a long, slow-motion journey, the dial turning and clicking back into place after she let go, her mushroom-colored fingernail searching through a mental haze of apprehension for the 3-hole.

“Lee?” I said, appearing from the mouth of the stairs. “What’s going on?” Lee held up a finger to me while she finished dialing.

Anne – fifth born

I sat on the roof outside my bedroom window, smoking a cigarette from Mom’s purse. It was difficult to navigate out the window with the sling on my arm, but I managed. Anyway, it didn’t really hurt, although at times I lied so well, I convinced myself that it did. I had waited for it to stop raining. As soon as it did, the sun burst through different slits in the clouds, proud beams licking the neighborhood to a glistening sheen. I grabbed a towel to sit on and climbed out. I noticed the red and black Zephyr driving up High Street just as I lit up. There goes June again, I thought, the lucky bitch. Everyone got to do everything before I got to do a damn thing. Mark had a mini-bike; he got it when he turned twelve. Now, just four days away from my eleventh birthday, I figured I would be able to get one too the minute I turned twelve, so I marked it on my calendar to start the countdown. Only 370 days to go. When Mom told me that I would have to wait until I was fourteen, that Mark was a boy and that was a different story, I was so mad I could have punched Mark and Mom right in the face. Instead, I clenched my teeth, turned red, mumbled the F-word under my breath, and went to my room.

“What did you say?” Mom had asked.

“Nothing, god!” I snapped and ran up the stairs. Occasionally stealing cigarettes was the only way I could privately assert my independence. That, and the intoxicating, almost erotic feeling of every so often stealing a beer from the refrigerator or from under Jonas’s bed and drinking it in the woods where nobody would see me and where I could bury the evidence.

I was thinking about the day that June and Jonas got that car, how we all took a drive in it. Mark and I were in the huge back seat, June, Lee, and Jonas all up front. Mark had punched my shoulder teasingly, and it took a moment before I remembered that it was supposed to hurt.

“Ow!”

“Leave her alone,” Lee said, turning around, slapping Mark across the top of his head.

“She’s faking!” Mark said and punched me again.

I bared my teeth at him and he made as if to slap my face. I winced away and he laughed. My arm looked so fragile in the sling, so tender. I had always been intrigued with slings and splints and bandages, and took any opportunity to be able to wear one, even if I had to fake an injury. Once after Lee broke her arm, I stared longingly at the full-length cast holding her elevated limb in traction, bent at the elbow.

I lay back on the sloped roof and closed my eyes, hands behind my head. I thought about the dream I had the night before, in which I was a boy making out with an older girl, kissing open-mouthed, the petal soft swell of a bare breast against my palm. Then I heard sirens close by, sat up and looked out at the street, but they had already passed. I didn’t see Mark running up the street moments later in that direction. Then, when I heard Mom screaming for her keys as if she were on fire, I climbed back in my room, secured the screen in place, situated my arm in its sling, and went downstairs.

Mom

Mom was thinking of ice, had it fixed in her mind like a photograph pinned to corkboard, static and crisp. She was standing on a ladder in the living room painting the wood trim a lake shade of blue, watching the lateral motion of her arm, the smooth horizontal strokes of the brush.

“I’m gonna go to Horizons and pick up my paycheck.” June said.

Mom looked out the window at the blurry sheets of rain drenching the crippled mulberry tree and beyond that, sweeping along the pavement. “No, don’t go just now,” she said. “It’s raining too hard.”

June moped out of the room. Our parents had decided to get the twins a car after their driver’s exam. They thought it would be useful to have them run errands, pick up and drop off Mark and me, go to the store, and do any variety of chores perpetually needed in our family of seven. Before long, June appeared again, keys in hand.

“It stopped raining,” she said, nodding toward the window. Mom looked outside at the glistening pavement, sunlit blacktop, slicked tar strips patching the cracks.

“Ok, you can go now,” Mom said. “And don’t forget your seatbelt,” she added, too late. The back door slammed, and she saw the big square Zephyr pull out of the driveway and glide down the street.

June – third born

June pulled her red and blue windbreaker over her T-shirt while coasting down High Street, then switched on the heat. She flipped on her turn signal and made a full stop at the stop sign, even though no cars were coming. Pulling out onto Lake Avenue, she felt a wave of exhilaration. She was driving now, had a car of her own—well, almost her own.

Jonas’s appointment with Rachel was today, she thought, and wondered how that was going. She knew that her twin brother was having sex even before he told her. She sensed the change in him. He never kept anything from her too long, so her suspicion was rapidly confirmed. June had been dating Travis for almost six months, but wasn’t ready for that.

“Maybe when I’m seventeen,” she told herself, picturing Travis’s face, the strong angle of his jaw, his brown eyes boring into hers. She kept her eyes open when they kissed because she liked the view she had of the side of his face, how it curved into his neck, wrapped by the blue and white sky beyond. They usually met at Seneca Park to talk and make out. A few times they had gone pretty far, and June had to grab Travis’s hand as it worked at unbuttoning her jeans.

“Stop that,” she would say. “I’m not ready for that.”

He always apologized sheepishly, mumbling how he’d gotten carried away.

The fact that Jonas was doing it almost made her want to try it too—until he’d gotten himself in trouble. Then she knew that she was right in waiting. Mom had asked her if she ever thought about it, but she turned red and said, “No way!” She laughed out loud at that thought, shaking her head. She had too much to lose: an upcoming trip to Paris with her advanced French class (she had become fluent), a shot at class president, and if she held her ranking for two more years, she would be valedictorian in 1990.

She noticed, now, the sunbeams over the lake to her left, how they exploded the sky and lit up the choppy water like shards of glass. Her head turned from the road to the sky to the road, then back to the sky. The thrashing blue-green of the lake against the autumn sky burst through with fire orange was stunning. When an open area offered an unobstructed view, June indulged in a long look. It was so beautiful that she didn’t realize she was holding her breath. When the car started drifting left of center, she didn’t realize that, either.

The smell of casseroles was nauseating. Also, my arm itched. The longer I scratched, the worse the green-gray pit of sick in my gut. The green bean casserole looked like what I imagined sick would look like, if it were food. Their buttery, creamy smell clashed against their image and made me want to vomit. The brownish tuna casserole and the one that looked like Hamburger Helper smelled bad. Together, they smelled like frogs, the ones that hopped from the creek from which Mark and I used to catch tadpoles and crayfish. That seemed like years before, but had only been weeks. Already, I could barely remember what it felt like to be a kid and do kid things.

Maybe it was a crayfish casserole. Mark used to pull off their pinchers and lay them on the ground where they would open and close, open and close–tiny, disembodied appendages with a mind all their own. Like how a decapitated head’s eyes still look around after it comes off, watching the body from a wrong angle, like beneath the feet, seeing its own thick toes curl and arch. At least that’s what I’d seen in horror movies. I’d never seen an actual dead body with its head cut off, but thinking about it made me think of June, her head slamming into glass.

When I walked into the ICU on that first night, holding Lee’s hand, there was a smell like medicine and plastic and dirty diapers. It was dizzying: the smell, the beeping, and the hushed voices in the dark. Only the nurse’s station was illuminated; most of the curtained-off beds were lightless caves with figures hunched over broken bodies. The room was a dark egg with a white and silver nurse’s station as its yolk. We walked a half moon around the yolk before we found June, watched over by Mom and a stern-looking nurse. I approached June, holding my breath, feeling my guts ball up in my throat. Her face was not her face. The pale, bloated, bulgy-eyed, cut and stitched object floating there against the pillow was monstrous. A tube disappeared into her neck like a power cord with jaws. Suddenly I felt fine, convinced I was playing a part in a horror movie and this thing in the bed would rise up and bare bloody fangs at any moment. Behind it all was the camera crew and the makeup artists and the guy who says, “Scene two, take four,” then clacks his board.

On the other side of the bed, Lee took June’s hand and cried.

“We’re here. June. We’re here. Anne and me, we’re here, we love you,” she said, her voice lower, tamped down with sobs. Inappropriate laughter threatened to erupt from me and before I could stop it, a little wail escaped, which everyone took for a desperate kind of crying. I felt a hand on my shoulder.

Lee rubbed June’s arm with one hand and held her hand with the other. I mimicked her on my side of the bed, mechanically did what she did, said what she said. June’s hand felt cold and chunky. I squeezed it. I rubbed her arm. “We’re here, we’re here, we’re here…” The cold hand turned my hand cold, and the monster face inflated. Her eyeballs were moving behind veils of pale lid. I leaned in closer to watch them. The delicate circuitry of veins in the domed eyelids seemed to slide around in translucent oil like shoals of tadpoles beneath the creek’s slick surface. “We’re here, we’re here, we’re here…”

Her head slamming into glass, her neck breaking. Snap! Frog and crayfish casseroles. I scratched harder, digging my fingernails in deeper until I felt pain and looked down to see a red, raw spot on my arm. I stopped itching.

“Anne, come in here and eat something, honey, you need to eat,” Dee said. She was Mom’s best friend, our godmother and neighbor. She came over after the accident, and cleaned and cried and cooked. People from church brought more food and flowers and cried. “Come eat,” she said.

Shatter! Snap!

“I’m not hungry,” I said.

Sliding veins, slipping, bulging. Crack!

“I know, honey, but you have to eat, now get in here.” She ladled the green gray slop onto a plate and the itch came back. The house had never been cleaner.

“We’re here, we’re here…”

“What did you say, honey? Come eat.”

Snap! Slip!

“We’re here.”

The skin was red and raw like a burn. My fingers were cold. I’d never seen so many casseroles, so much food. Cold, heavy hands. Thick chunks for fingers. Crack!

“What did you do to your arm?” She said, suddenly right in front of me, the bulk of her nearly on top of me. She grabbed my hand and rubbed my arm. I felt my face get wet and tasted vomit in my mouth. I slapped my hand over my mouth to keep from puking, and realized I was crying.

“Oh honey,” she moaned and smashed me against her, a warm, soft mass.

“We’re here.”

Slip!

“I’m here,” she said.

I shook against her, swallowing sour saliva, snot and tears between my cheek and her bosom. On the wall beside us, there was a shelf lined with five silver saucers, our baby cups. June’s was small and coppery and smooth like a shot glass or an egg cup, identical to Jonas’s, distinguished only by the engraved names. It was two down from mine, which had a small handle and a lip around the top. The pewter surface reflected a far away distorted image of my wet red face jammed against Dee’s sand-colored blouse, her glasses warped into one huge lens framing a melting brown eye.

Paris, Day 1

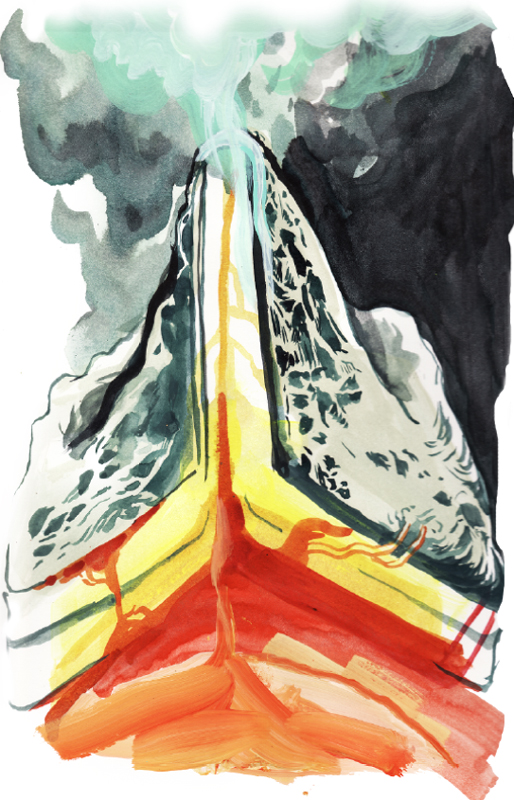

After several hours that felt like several days sitting nearly motionless on the plane, we arrived in Paris–June, Lee, Mom, and me. The European morning was the crest of our midnight, witnessing us bleary-eyed, unloading June’s traveling wheelchair from the back of a taxi then guiding it over cobbled roads, sloshing through small blue pools of foam and rainwater. Mom had secured a hotel for us but it was too early yet to check in. We dropped our luggage off in the lobby and set out to find a café where we could breakfast with the heft and the weight of it all. It all being what got us there, finally, after twenty years. June would finally see the Mona Lisa, and I would be the one to show it to her. I admit, I half expected, albeit half rejected, that she would experience some kind of profound shift upon seeing the long awaited painting. It was apt that a simple, dark-haired woman with the wisp of a smile trailing on her mouth (as though she had just finished smiling and was now resting her face from the effort) would be the thing to blast a new pathway in June’s brain, igniting old synapses, blowing the dust off whole sets of stagnant cut-off data, kindling an electrical storm of activity in those dark, warm chambers so long sleeping like a dormant volcano.

June had a gallon-sized baggie of disposable cameras and took pictures of everything. Perched sanguinely in the wheelchair, she snapped away at the facades of buildings, the street ahead, down alleyways we passed and, most famously, at the two asses of whichever of us was walking ahead. Several times during that walk, I looked at my sister smiling against the backdrop of an old cobbled road and thought it emblematic of something important: Streets in a very old town, how they snake every which way, laying spontaneous passageways for walking–they mirrored the trajectory of our convergent paths over the prior two decades, which had been anything but the neat grids I thought they’d be. And they had led us here.

This was it. The apogee of the aftermath of a brain being damaged, bones being smashed, a neck being snapped–the brain and bones and neck of a sixteen-year-old girl in a family like ours.

We sat down at a café, encountering the first of many problems we’d have: the size of the place. All tables were so close together we could barely wedge two bodies in opposing chairs, much less park a wheelchair. But the waiter scurried to accommodate us, pushing one square chrome table to the side and whisking away a chair from the neighboring table. He then stood back, hands offering us to maneuver her in.

“Merci, merci,” June said several times.

Lee said, “Thank you.”

The waiter took the French menus and replaced them with English ones, which we studied in silence. “What time is it at home?” June asked.

I opened my mouth to tell her, having quickly calculated, but then caught Mom’s warning glance and short shake of the head.

“Let’s rearrange our sense of time to get acclimated,” Mom said, winking at me. “It’s about 6:30 in the morning here, so we’re having breakfast. When we get into our hotel room, we’ll take a nap to catch up then go hit the town. We’ll be nice and tired by evening and by tomorrow, our bodies will be on Paris time,” she said.

She was right. Telling June what time it was at home was likely to panic her and cause her to lay her head down on the table right then and there to fall asleep. She was, post-accident, very much a creature of routine. Eating and sleeping at certain times and intervals were non-negotiables for her.

Most items on the menu involved egg, which was undesirable for everyone. Although Mom ended up ordering an omelet, the rest of us got fruit and croissants. June got some fromage. She kept surprising us by recalling her French, spoke it with everyone we encountered and, for the most part, people understood her.

“She was fluent before the accident,” Mom said proudly. “It’s coming back to her now.”

Despite her exhaustion, June was possessed by joy. She even looked different, her skin suppler, smoother. Her acne appeared less severe and her mouth always had the hint of a smile. When the waiter returned to check on us, I watched June’s mouth slowly sounding out slippery French syllables: “Puis-je avoir un petit jus d’orange s’il vous plaît?”

The waiter nodded and hurried off. We all stared at her, dumbfounded.

“I asked him for orange juice,” she said.

Mom laughed and beamed. I nearly cried.

The wondrous plasticity of the brain–how it forges new pathways to dig up old, buried information. I wondered then, how much of learning is actually a remembering of something long forgotten, yet known.

If the Parisians we encountered had trouble understanding June, it wasn’t for her lack of accuracy with the language but rather the slow and strained sound of her voice. When they spoke it back to her, the rapidity skipped over her head like a flat rock skimming water. She had to ask the person to repeat several times and still lost most of what was said. She got much more than the rest of us did, though. It’s fascinating, really. The same letters, arranged differently, forming new, unfamiliar sounds with corresponding meanings we struggled to puzzle out. What’s even more fascinating was having June as our primary interpreter of that meaning, when, at home, it was often the other way around. Right away, it filled her with a sense of importance and purpose that made her visibly buoyant.

A few days after the accident, I waited at the end of our street for the school bus, holding my book bag like it was a cat, cradling it in my arms with the strap spilling over like a tail. I felt the street stretch back and up behind me. If the bus hadn’t come, I might have tumbled forward into the road and been crushed under it.

The double doors opened and Mrs. Kitter looked down at me from her seat. Her eyes were red-rimmed and she forced a smile. She had been our bus driver forever, all of us. She had started with Lee in kindergarten, had driven June and Jonas all through their primary school years, then Mark and me, and now just me. Next year, I would join Mark at Rogers Middle School, and Mrs. Kitter would be done with us.

I climbed up into the bus, avoiding eye contact. The way anyone outside my family looked at me since the accident was unbearable–a cross between fear and incomprehensible pity. The narrow aisle between the bench seats was black and corrugated. I stared down at it and made my way toward the back without looking at anyone, but the feel of their eyes on me and the sound of my name and June’s name in their whispering turned me red and sweaty. I hadn’t eaten a thing in days and the acid in my stomach burned for something, anything to digest. I swung into a seat, scooted all the way to the window, and plopped my book bag next to me so nobody would try sitting there. The kids in the seat in front of me instantly got up on their knees and turned around. They leaned over the back of the seat with crossed arms and peered at me.

James, a known troublemaker, sat by the window looking at me with blithe eyes. Beside him sat Devon, a curly-haired, chubby girl who lived in a big house on the lake not far from us. She was an only child and her parents were weird: Her dad was old and wore adult diapers, and her mom was too beautiful and had lots of affairs, the details of which she discussed with Devon before she even had pubic hair. I knew because she told me, unbidden. They once invited me to swim at the country club where they were members. In the locker room after we were done, Devon stripped off her wet bathing suit, sat cross-legged on the bench and plucked at some baby black hairs that had started to sprout between her legs. “I’m starting to get pubic hairs on my vagina,” she had said proudly.

That image is what came to mind every time I saw her on the bus in the morning. She had always been jealous of my big family and would try to compensate by showing off her expensive gifts. Once, when I got a bike for my birthday, the basic model from Odd Lots, Devon showed up later that day with a name brand, shiny purple and silver bike with gold tassels on the handlebars.

This particular morning I might have traded my life for Devon’s, if given the choice.

“What happened to your sister?” she asked, a hint of satisfaction in her tone, though her expression was one of genuine concern.

I didn’t answer, just looked away and stared out the window, scowling. James instantly lost interest and turned back around, mumbling something under his breath.

“What’d you say, James?” Devon asked with a little giggle.

“I said her sister’s a slut,” he called out, loud enough for everyone to hear. My whole body instantly turned hot and without thinking, I shot up out of my seat, reached over, grabbed a fistful of his hair, and slammed his head hard against the side of the bus. The sound of his skull against the metal interior of the bus was a clean crack followed by a groan from his throat. I thought he might have started crying then, but I couldn’t be sure because I dropped into my seat just as quickly as I’d leapt up and went back to staring out the window, feeling the heat in my face, shaking a little from the slowly subsiding adrenaline. Slamming his head like that felt good but I easily could have killed him. Everyone gasped when it happened, and Mrs. Kitter pulled the bus over.

“What’s going on back here?” she demanded in her brusque voice, stomping back toward us.

“She pulled my hair and slammed my head into the wall,” James said, whining. I felt Mrs. Kitter look at me but I didn’t budge, just sat with my arms crossed and stared unwaveringly out the window, my eyes fixed on a fire hydrant.

“He called her sister a bad name,” another kid said from somewhere behind me. I looked up then at Mrs. Kitter. Her lips clamped together and she glared at James.

“Don’t you say anything about her sister again,” she said to him, stabbing her index finger in his direction for emphasis. The corners of her mouth trembled. She didn’t look at me again, just turned around and walked back to the front of the bus. There was complete silence and stillness in the aftermath, the great hull of swaying bodies starting again to move down the road. The engine’s wheeze and the hiss of the gears was the only sound.