First Published by Landon Books, New York 2011

First Electronic Edition by Landon Books, 2011

Second Electronic Edition by Landon Books, 2012

http://www.landonbooks.com

Copyright Joan Hawkins, 2012

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by

way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out,

forwarded, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s

prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published

and without a similar condition including this condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner

Without written permission, except in the case of

brief quotations for review purposes.

Editing, book and cover design by http://Cyberscribe.ie

ISBN 978-0-9837348-1-9

About the Author

Joan Hawkins was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She went to Bennington College and New York University School of Social Work. Her first novel, Underwater, was a cutting edge cult novel that explored female sexual boundaries. It was published by G. P. Putnam in 1974 under the name of Joan Winthrop, and will soon be available as an e-book. She now lives in New York City where she practices psychotherapy.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

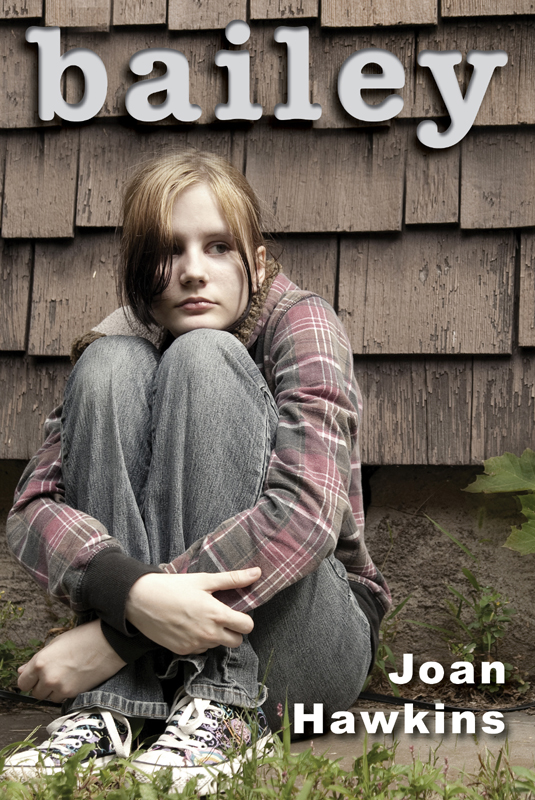

Title Page

Copyright page

About the Author

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 1

She said that Bailey was her name, her only name. Never had the medical staff at Stockbridge known a patient to dry out so uncomplainingly.

Although at fourteen years old she was the youngest alcoholic ever admitted to the exclusive sanitarium, Bailey looked like a matron with a rough-skinned, red fleshy face and a portly body. From the morning she arrived, she appeared to accept Stockbridge as an unloved child does camp. Often melancholy, but always stoical, she made herself at home as quickly as she could. She remarked at once that the buildings and the grounds reminded her of a country club, which was considered astute, because between the two world wars, Stockbridge had been a luxurious resort for golfers at the edge of the State’s western hills.

Bailey loved the food at Stockbridge. She chatted with the waitresses and walked into the kitchen to compliment the cook on the spaghetti. She loved her corner room with two windows on the third floor; and the carpentry shop, where she set about making a model of her childhood home. She walked about with a shy smile and a quick, light step. She greeted the other patients with a slide of her hand, palm out; moving between them as though to erase their general irritation. At this, the hostility of Jim Peabody, the sanitarium’s youngest male patient disappeared as though her sliding palm were a magic wand.

“Suck shit, man.” Bailey’s cheerful tone challenged the twenty-two-year-old’s frigid composure. On the spot they became the sanitarium’s famous young couple. Snobbish, reclusive, Jim Peabody accepted the girl’s foul-mouthed adoration as though it were his fate. That they were drawn together by the symmetry of their delusions became the staff’s favorite witticism. The girl thought she’d castrated her father while the boy was convinced that his father had castrated him.

Jim Peabody’s pretensions to grandeur angered the Stockbridge medical staff. Ignoring the psychiatrist in his mandatory therapy sessions, he read books on military history. His father had been the youngest captain in the American Army before becoming a famous doctor, and it was his mission at Stockbridge to prepare himself for the day his father died. As the future head of a distinguished family and the custodian of his father’s fame, he had no time for the soft knowledge of introspection and memory.

His decade of alcoholism, the cause of his Stockbridge stay, he repudiated with lordly aplomb. Drinking was a hazard of the socially powerful – not a disgrace. Always it had been the cover for impossible crimes that could not be exposed. It was obvious, wasn’t it, what the facts on his admission chart must be?

Bailey, however, with her shy courtesy and democratic respect, her graceful heft and fine eyes, was immediately the sympathetic focus of opinion and anecdote. Her devotion to Jim Peabody, and her submission to his schedule of self-improvement, combined with her explosive prurience in his presence, were thought to point to a reality that reversed the current of aggression, making her its victim. The child of alcoholic parents, neglected by her mother, by her father abused, Bailey endured her load of unconscious agony with the same strong grace with which she bore her fat.

If an intern were idealistic and vigorous, Stockbridge Sanatorium was the most depressing residency one could pull. Since the owners had no intention of coping with the acutely disturbed, only the alcoholics and the senile paid the enormous bills. In this swamp of decadence the friendship of the oddly aged youngsters provided relief to the underused staff, who named their process “The Volcano.” Under the pressure of Bailey’s pornography, it was at first thought that the terrible weight of their repression would blow sky-high, leaving them supple, hopeful and bound for the world.

Then it was circulated that the meeting of the two strangers was only apparent: the young man’s famous father was paying the shocking bill for them both. A sinister contrivance was felt to be at work.

At table, walking in martial unison through the halls, and especially when they stepped out of the thick woods at the edge of the golf course, at the end of their afternoon walk, they looked to be escaping some great fright, as Hansel and Gretel had fled the witch. But the powerful figure that controlled them both could only be killed by the truth and not by the phantoms of a grandiose egotism that only the wealthy and the insane could sustain.

Not one of the idealistic interns leaving Stockbridge at the end of their term kept the young people in mind. It was too depressing.

Bailey lost the last point with a casual lunge of her racket and jogged smiling to the net. “Suck my ten-incher, girl – you pussy player.”

Returning the yellow tennis balls to the can, Jim looked at his unique friend with imperturbable eyes. “Sore loser, kid. I just played your backhand.”

“You played shit, sister.”

As Jim turned his back to her, Bailey raced around the net and stood at his side, timid and afraid. As always, her nervous contrition induced in Jim the sensations of a person he’d never before felt himself to be. Intellectually brilliant, of compelling moral influence, he apparently inspired in Bailey an almost helpless worship. To costume this person in proper attire, three weeks previously he’d written his mother, asking her to send up his father’s riding boots and the short khaki captain’s jacket that he’d worn in the previous war. The feeling of the jacket and boots, their image in reflecting surfaces, confirmed the girl’s admiration in glorious reality.

“My mouth just opens, Jim. I never know what I’m going to say. I never feel mad at you.”

Bailey’s keen, constant and uncritical appreciation was the furthest from hostility that Jim could imagine. An eruption of her unfortunate social background was the only way he could explain these profane geysers. No soap in her mouth as a youngster, he supposed; never been whipped as he had, or locked in a room. While it was probably too late to introduce physical punishment as a curb to her hysteria, he was determined to eradicate her vulgar accent.

Flat and blunt, the harsh tone of Bailey’s speech would alone encourage mental depravity, but Jim understood the brain. Accommodating different sounds, Bailey’s brain would develop different pathways. The old ones, tormented to near epilepsy by ugliness, would dissolve, and with them the filth of her helpless tongue.

“I never see any anger, Bailey,” Jim smiled at her. “I never feel any, but what I hear has got to stop. It will be stopped! We’re working on the problem. In fact,” he glanced at his watch, “we have an hour and a half before dinner. I’ll shower, dress and bring the tape recorder to your room in twenty minutes. What’s this? Do I see mutiny in your eyes?”

Jim laughed at his extravagance – could a kitten be a lion? Then pushed Bailey forward. Accustomed to the girl’s alacrity, he stopped at her grudging weight. Bailey looked down at her sneakers.

“It makes me sick talking different.”

“Talking correctly.”

“Talking like mother, talking like you – it makes me sick.”

“I know it’s a strain at the moment. But you know our way, Bailey. An hour a day and very soon no one at Stockbridge will believe you ever sounded like a guttersnipe.” “Fuck you!” Bailey shouted and for the first time her straight-on eyes were grim.

“I beg your pardon.”

“I like doing math and reading and learning about history, but it makes me feel awful.” Bailey peered up at the sky as though to drain the ache in her throat. It made her miserable that Jim hated the way she’d spoken since birth. She pitied her father, whose accent had offended squadrons of aristocratic ears.

“How do you think I feel when you talk filth? Do you think I can live with that indefinitely? Do you think you’re tolerable if you’re not working to rectify the situation?”

“Fuck me! It’s not my accent that swears.”

“Your mindless obscenity is a habit, Bailey. When you learn to speak the King’s English, you’ll be relieved as well as me.”

“My ass!”

“Your future.” Jim marked his humor with a stiff smile. “I want you out of the shower, dressed for dinner and seated at your desk in twenty minutes. You will learn to speak like a lady, Bailey.” Walking off, Jim waved his hand over his shoulder, “twenty minutes.”

“Don’t leave me! Help me!”

Chapter 2

Out of Jim’s presence Bailey was frightened at Stockbridge, especially in the halls and dining room of the sanitarium where the patients looked like dead fish as she passed their erasing eyes.

Back home Bailey had had her vodka to dull the pain of her family’s dislike – and a day-long slide of television shows to pass the time. But at Stockbridge the same programs pushed her out of her corner room to the winter woods where she first saw Jim Peabody, a wintry tree himself with his numb, serious tolerance.

“Your father sucks shit,” she’d been quick to inform him.

Looking up from his fly, Jim observed the blush of her ferocious shame with bleak, quiet eyes. “Worse than that.”

Jim acknowledged her anxiety and terrible tongue with total indifference to their cause.

“All the Stockbridge patients are dead fish,” he allowed with a frosty smile. But he and Bailey would not drown in the past, as other patients had, but work every minute of every day to survive in the future.

As Jim’s schedule and sarcastic patience blocked off the past – she’d learned tons in a year – Bailey was just as happy as she’d been at home when locked in her bedroom and enthralled by the truth and beauty of the television dramas. But this year she wasn’t drinking. Fear stepped back while Jim worked with her. She was horribly obscene. Out of nowhere, waves of filth smashed against Jim’s rocky composure. Oh, the deep lines in this boy’s face, as though age had made a mistake and drawn itself too soon. His patience and glancing humor, like ice shining in the sun, had saved her from a fear that had kept her on her feet in aimless wandering, that had made her eat too much and turned sleep into the goal of her days.

Jim was a god with his feet in her life. Like a dog, she’d allow herself to be trained, but she was deeply ashamed when she heard her “acceptable” voice on the tape recorder. A dog putting on the dog.

Brick building turning black. “Twenty minutes,” Jim commanded, still in sight as he walked through the evening shadows. There were snakes in the ivy patch and doves cooing as if to give voice to the loneliness that Bailey could no longer endure. Groaning, she plunged in a tip-toe rush towards a lesser dread.

Chapter 3

An hour before supper Jim Peabody knocked on Bailey’s door. Admiring the fresh shine of his riding boots, he relished the emphatic clicks of his heels as he trod the linoleum halls to Bailey’s room. His boots, captain’s jacket and powerful tape recorder were his silent insistence that the reform of her speech must continue.

Bailey lifted the model house from her work table to make way for the tape recorder. “Hold it, Captain, the glider plane fell down.” She put glue on the end of a thread and stuck her hand through the open back of the well-made house. Crouching, she looked through a window.

“Fuck me! It’s turning on its string.” She lifted her thrilled eyes to Jim. “It’s got a shadow.”

Jim looked at his watch, his boots creaking with impatience.

Putting the model house on her dresser, Bailey came back to the table. “I like the way I sound. I talk like my father.”

“We’ll both survive our fathers, Bailey – with work.”

“You sure survived my sister, Cary.”

Setting up the tape recorder, Jim did not hear Bailey’s flash of bitter resentment. When he pulled the chair from under the desk and sat, Bailey had taken her favorite perch on the end of her bed. Accustomed to the folded legs and straight spine of painful effort, Jim disliked the sag of her shoulders and head as she leaned back against the wall, her legs stretched slackly in front of her.

At the soft hush of the turning tape, Bailey glared at the severe young man so proudly wearing his powerful father’s war jacket and dismally listened to her mother’s elegant accent erupting from her chest.

“Captain Peabody! You must educate yourself. You think Cary Bailey is meat in the supermarket, the chicken and the steak, don’t you know. All wrapped up tight in that glossy stuff. You made a hole in her wrapper. Her juices made a mess.”

“You’ve got it, pal.” Jim’s eyes brightened in icy pleasure.

“Cary adores housework, can you believe that? In bed, watching the cartoons I’m astonished by her drudgery. The speed of achievement is essentially the appeal of cartoons. Real life demands such laborious effort.”

Bailey’s revolted eyes dropped to Jim’s trousers. “In a cartoon I’d be fucked blind in an instant, but you – clip clop, clip clop, over hill, over dale – such a bore.”

“All our work is to such good purpose, Bailey. I’d almost swear to our common heritage. By God, I’m proud of you.”

Bailey sickened in the stream of his pride. Panting, her arms and legs spread wide on the bed as though her weight had become a crushing stone. Her face and neck were red and wet. “I’m too full to go to supper. Full of SHIT!” Bailey shouted in her native speech.

Jim bristled at her ugly voice. “You’re full of your past,” he sneered.

“The unspeakable past, the past of the entire human race – so what? The unconscious lust of fish and bugs and reeking mammals is violent poison in our guts. Be glad of the eruption. You’ll be clean all the sooner for the violence – but don’t brood.”

“It’s your past too.” Regarding him in sallow despair, Bailey seemed to threaten the grip of her clothes with her pasty expansion. Jim could almost see her buttons flying. “Whenever you make me sound like a broken jaw, Jim, your past comes out of my mouth.”

“I don’t pay attention to your fantasies, kiddo. Shall I explain to you again the impossibility of any social connection between our families?”

Bailey crawled to the top of her bed and curled round her pillow. “You don’t like me.”

“No! No! No! Not the old voice,” Jim clapped his hands like an irate schoolmaster. “Your old voice is gone forever. I never want to hear it again.”

Bailey got to her knees to pull the yellow curtain across the window then crashed down around her pillow.

“Get up, damn you!” Jim snapped back the curtain, and opened the door.

Answered by the girl’s woeful silence, Jim slammed her bedroom door. His clicking heels sounded hollow in his ears as he went into the large dining room to eat his supper alone.

Chapter 4

In front of the clubhouse Bailey swung up on the stone lion that guarded the granite steps. Its twin lay vigilant a few yards away. In the long, imaginary rides she used to take with her brother Tom, that was always his mount. Now, he’d “matured” as he mockingly called it and played golf as often as he could manage. Bailey spotted him this very minute, hopefully beyond the range of the ball that Peabody was about to smack off the first tee. The long, green fairway probed the distance, narrow as a tree trunk, when Bailey lost the view. The red flag at the second hole caused the child to straighten her back as she rode and clenched the stone lion with severe pride.

It was after supper, five days before her tenth birthday, and the serious excitement could begin. Like a stoker at a fire, Bailey watched over it. She fueled it gently, the bellows of anticipation barely used, then, on the last night, extravagantly pumped.

Mrs. Peabody teed off and waved to Bailey on her perch. Bailey admired the sharp creases of Dr. Peabody’s trousers, their intense whiteness. Tennis players had to wear white while the golfers were allowed to wear what they liked. Bailey wouldn’t dream of being a golfer. Wearing whites was a rule she vehemently approved of. Men had to wear jackets and ties in the dining room and no woman in slacks could eat anywhere in the club. Her father would not lower the standards for anyone. Not even the President of the United States could sit in the bar or dining room in his shirt sleeves, although he might be allowed to drink his cocktail on the terrace.

It was the oldest country club in the entire nation and, Bailey had no doubt, the richest and most beautiful. The other part of the club was at the bay, a mile down the road. There was a city of cabanas set around an enormous swimming pool, which Bailey helped to clean in the spring and fall. Beyond the pool, there was the beach. There were sailboat races in the bay. At the mooring, the masts pitching as the water moved, the sound of bells was continuous, bells tied high on the rigging and gaily sounding as the tide and wind moved the heavy hulls.

Bailey slipped down from the lion. The afternoon was so warm she cut across the golf course on her way to the bay. She might take a boat and row out into the sound of bells. She might even swim. At the bottom of the great front lawn, a line of huge trees had turned gold in the frost that hit last night and Bailey wondered, running towards them, why she was thinking thoughts for a second time and why she knew just where she would stop, excitement a pain in her chest, as she felt the magic aura wear away. “This has all happened before,” she thought, as if there could be no plainer answer.

Tom and the Peabodys were playing the short fairway of the first hole, with Tom advancing quickly to the green. The fairway was a puny joke. Lots of players got a hole-in-one and even Tom made it in three shots. As she stepped off the green a ball landed with a gentle bounce and stopped a few inches from the cup. Bailey reached up from the sand trap and gave the ball a shove. In a second, she was flat on her stomach again and hoping that Mrs. Peabody, and not her snooty husband, would get the benefit of her little boost.

“Congratulations, Polly. You’ve got yourself a hole-in-one.”

“The hell I have! I’m going to give Georgie holy hell tonight! Her children are running wild.”

“She’s without a husband, my dear. Jack Bailey’s been gone for almost a year.”

“All the more reason she should manage her dreadful children.”

“The little blondie is sort of cute.”

“I can’t separate her face from her accent, I’m sorry to say. Our poor Jimmy.”

“I’m not following you, my dear.”

“A cheap little trick like Cary Bailey is an attractive menace.”

Dr. Peabody’s piercing laugh sounded fagged as though it were an overused weapon.

“You know quite well,” said his wife, “that boys like Jim don’t go after that kind of girl – they fall into her trap. She’s a slut!” Bailey had never heard such confident hatred. “Don’t tell me you want Jimmy to marry her.”

“Naturally, I don’t. But for good old-fashioned reasons, Polly. I don’t deny, as you do, that they’re in love.” Tom’s sarcasm was sentimental compared to Dr. Peabody’s scorn.

“I don’t know why Cary loves our pathetic excuse for a son, but love him, she certainly does.”

Bailey’s ears, as the sound of their voices retreated, were a whirlpool of icy grief. Poor Cary!

The light of the sun lit up the moon’s dead surface. Bailey ran like mad down the fairway, then rested and walked backwards. The roof of the clubhouse with its tall chimneys was a cruel city twirled by the indifferent earth through sun and shade. Her stone house was bullied by the pine trees. The highest branches hung over the roof and brushed the window screens as the wind blew. The sound was dreadful as she dashed up the walk to the kitchen door.

Cary was alone in the yellow kitchen, drying her rolled up hair in the oven. Bailey climbed up on the counter behind her and picked up a drumstick from the platter. There was no taste or smell as she chewed and swallowed, and no sound as the bone missed the garbage pail and fell by Cary’s sneaker.

“Hey,” her sister mildly protested as she closed the oven door. Her head was huge with pink hair-rollers because it was Saturday night and she was going out with Jim Peabody. Because she was always behind in her chores and her thick hair took so long to dry, Cary always had to bake her head. She looked so good in her jeans and soccer shirt. Thin and dark, she looked as good as Tom.

Bailey hated the hair-rollers and the tight ring of hair that Cary unlatched and felt to see if it was dry. She hated the dress and high heels she would change into.

“Why do you put up your hair when it’s already curly?”