ISBN: 9781619273870

Introduction

Survival

Love

Humor

Addiction

Philosophy

Adventure

Lament

Hope

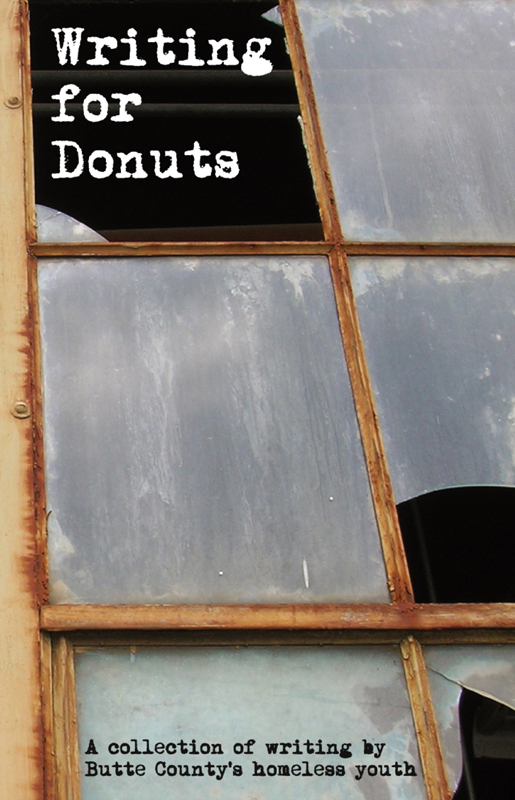

The first time I visited the 6th St. Drop-in Center, I left feeling like a complete failure. I was supposedly there to tutor someone, but who that person was, and what subject they needed help in were mysteries to me. At the time, I was finishing grad school while working part-time with the Butte County Office of Education’s School Ties program, where I still work today. Our program serves the homeless and foster youth population of Butte County, giving out backpacks and school supplies every August, making sure homeless kids have a bus pass so they can get to school, tutoring in every grade and subject, and ensuring that educational rights are upheld. But that day in 2008, I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing.

The staff was nice enough, but they didn’t really know what I was supposed to be doing either. No one had worked out the logistics yet, of who needed help (and who was willing to accept it) and how to make sure they showed up. So I sat around reading a book for most of the hour I was scheduled to be there, feeling guilty about the $10 of taxpayer money I was being paid to do so. The kids who were hanging around ignored me for the most part, like they ignore most newcomers. I remember having the strange and awful sensation that I had become a teenager again, and with that sensation came a rush of confusing and conflicting emotions. I left that afternoon feeling sick and discouraged, plagued by memories of my own misspent youth, memories I’d mostly managed to repress for years.

Unlike a lot of 6th St.’s clients, I never had to sleep under a bridge as a teenager. But I did see some tough times. After my mom and stepdad divorced when I was 12, my mom and I went through a five-year economic shitstorm that saw us moving every couple of months, staying with a series of weird friends and roommates, sleeping in a little boat at the marina, living in a yuppie couple’s basement with the shower in the kitchen and the fridge by the toilet. I didn’t adjust to it very well and my mom had to pick me up at the police station on a more or less regular basis for a while. I got kicked out of eighth grade twice and went through three high schools before I dropped out at 16. The one thing that saved me, besides my mom’s tireless efforts to get us back on our feet, was getting my diploma through the California High School Proficiency Exam. Had I not passed that test, I can’t imagine where I would be today. I don’t want to sound dramatic, but that piece of paper saved my life—the jobs it allowed me to get kept me fed and off the streets, and eventually it got me into community college, where I would start down a long and winding (and as yet incomplete) path to a career as a writer/educator.

I’m stable now, or as stable as any middle class American these days, which is sadly not stable enough. But the rough days of my adolescence left me with heavy emotional baggage. The alienation and shame I felt as a kid on the margins of society never quite went away. I get depressed sometimes. More often, I get paranoid and have to resist a tendency to lash out at people, a survival mechanism I developed to keep people from getting “too close.”

Leaving the Drop-in that afternoon, I realized I couldn’t just sit there every Wednesday and wait for people to ask me for help with their homework. I had to make a connection—with the youth, with the staff—I had to engage them in something meaningful. It had to be casual enough that anyone who walked in could participate, while still having a useful educational component. And to bait the hook, I needed an incentive—some small gesture to show that I valued the time and talents of those who got involved. What I came up with was exactly what I would’ve responded to when I was younger.

The next Wednesday, I walked into 6th St. carrying a big, pink box of donuts and set them on the table along with some paper and pencils. Then I sat down, took out my notebook, and began to write.

I hadn’t finished a paragraph before hearing “Hey, whose donuts?”

“It’s Writing for Donuts day,” I answered—still my stock reply today. “Wanna write for a donut?”

Thus began the Writing for Donuts writing workshop. Since then, I’ve met hundreds of young writers at 6th St., teens and adults of every gender and orientation and background and belief system. They’ve each enriched my life in some unique way, and I’m glad to have shared donuts and stories and jokes with them over these last five years. I’m also proud of the fact that many of the youth I’ve met through the writing workshop become School Ties students and went on to earn diplomas and pass GED tests, giving them a well-deserved sense of accomplishment and hopefully giving them a better chance at a decent living.

Doling out unhealthy snacks in exchange for hasty prose fixed my problem of not having any students, but after a couple of workshops, the writing began to pile up, and I felt like some of it was good enough to publish. So I threw together a one-page zine, made 10 or 15 copies, and brought them to the next workshop. Everyone loved it. As of this writing, WFD zine is on its 93rd issue. It’s become a forum for self-expression, a community newsletter, and a platform for ideas ranging from terrifyingly radical to undeniably sensible. I can’t say exactly what impact WFD zine has had on the constantly changing microculture of the 6th St. Drop-in, but I can report that if I’m a week late in publishing it, everyone there wants to know why.

If you’ve ever had anything you’ve written published, no matter how small the publication, you know what a thrill it is to see a stranger reading it. That feeling fades after a while, but I’ve discovered that I can get a similar thrill from watching a writer read their own work for the first time. It is a big deal to see your thoughts in print, and I consider it a privilege to have made that happen for the young writers of WFD.

I also consider it a privilege to be able to publish some of those stories here. Huge thanks goes out to the City of Chico Arts Commission for funding this project. I know this book won’t solve homelessness in Butte County, and I understand that budgets are tight. But there is real value in providing first-hand documentation of what is always referred to as “The homeless problem” in our community through the lens of those who are actually living it. In the endless debate over what to do with “The Homeless,” we tend to forget that we are not dealing with some special interest group. We are dealing with individual human beings who are caught in a cycle of poverty that is not of their own making. We forget that these are not some invading nomadic outsiders—these are our neighbors, our colleagues, and in the case of a lot of the writers in this book, our kids.

I was reading the other day about an ancient culture in South America who offered to their gods a sacrifice of children each year. They thought it would bring them good fortune to pick a few of the tribe’s favored sons and daughters, hike them up the Andes, give them some maize beer, and let them freeze to death in their sleep. Today we would consider such a culture barbaric, and yet, are we doing any better for the kids in our town who have found themselves abandoned to the streets? I like to think so. But if we are, it’s only because we found the empathy and moral strength to support places like 6th St. Drop-In Center, Torres Shelter, The Jesus Center, Catalyst, the Esplanade House and the many other groups in Chico that help individuals who, for whatever reason, find themselves homeless. This support saves lives, strengthens our community and needs to continue.

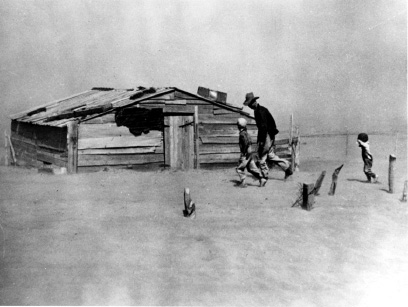

I’m not sure how, but a lot of people seem to have forgotten lately that we are still reeling from the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. The writers of this book have not forgotten. Their reality will not let them forget. It is my hope that those who read these stories won’t be able to forget anymore, either.

–Josh Indar

Remember when you were a kid, around 12 years old? What were you doing? Probably going to school, living with your parents and still being a child. I never got to have any of that. At 12 years of age, I was learning how to survive on my own.

By twelve, I was already a hardcore drinker, bouncing around from house to house, because I didn’t have a home to call my own. It all started when my mom and my oldest brother came home from the bar one night. The whole thing is still kind of a blur. All I really remember is the police hauling my mom off and the ambulance workers trying to take my brother to the hospital. He had blood gushing from his head, but he was too angry to go with them.

From that point on, my life changed, and it was never the same again. By the beginning of 2008, I had just turned 13, and I had already burned all my bridges with the people I was staying with. So I was dumped on the streets. I would have to say 2008 was the worst year of my life. I was new to the streets and scared out of my mind. Within a six-month span, I was almost beaten to death four different times and sexually assaulted once. I wanted to forget so I turned to pills and even more booze than I was already consuming. Because of the heavy drug use, I don’t remember much of the rest of that year. All I know is that I’m still here. So I must have done something right.