First published in 2014 by

Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd

1 Spencer Court

140 – 142 Wandsworth High Street

London SW18 4JJ

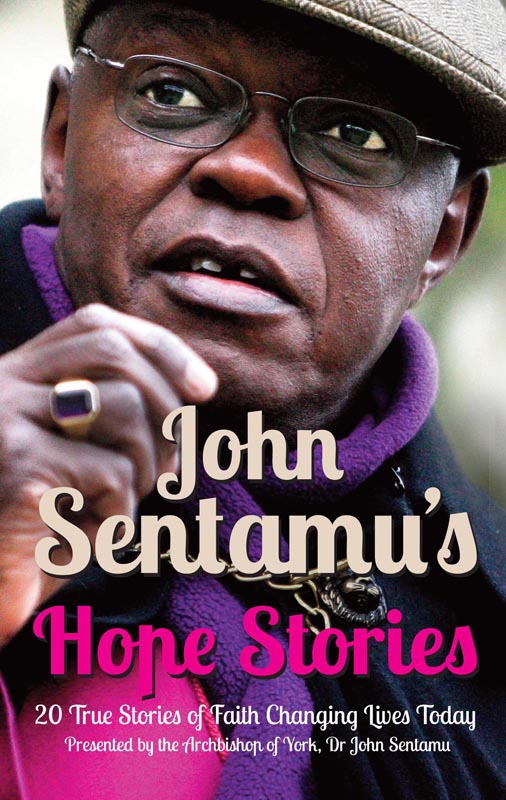

Presentation and Introductions © 2014 John Sentamu

Stories written by Carmel Thomason

The right of John Sentamu to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-0-232-53109-1

Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard

Version Bible copyright (c) 1989 the Division of Christian Education of

the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of

America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Phototypeset by Kerrypress Ltd, Luton, Beds

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

1. ‘Power in saying how you feel’ – Jasvinder Sanghera

2. ‘The Lord has forgiven me’ – Jim Race

3. ‘Taking my heartache away’ – Kelly Varley

4. ‘A full life’ –Nick Barr-Hamilton

5. ‘Everything in perspective’ – Jenna Gill

6. ‘We’ve all got a direct line’ – Elizabeth Pepper

7. ‘Lives can be transformed’ – Stefan Heathcote

8. ‘Learning to like ourselves’ – Ann Sunderland

9. ‘Our hope in his hands’ – Dianne Skerritt

10. ‘All I had to do was ask’ – Joanne Gibbs

11. ‘Families are made in heaven and on earth’ – Rachel Poulton

12. ‘A second chance’ – Andrew Hall

13.‘ Knowing I’m not alone’ – Patricia McCaffry

14. ‘A father to the fatherless’ – Ian Williamson

15. ‘Spiritual spinach’ – Andy Roberts

16. ‘God as my anchor’ – Luke Smith

17. ‘My life mattered’ – Shaun Turner

18. ‘God had other plans’ – Tracey Ingram

19. ‘I’m 59, and my life’s just starting!’ – Paul Myers

20. ‘Supported by other people’s prayers’ – Marilyn Marshall

1 ‘Power in saying how you feel’

‘So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them’ (Genesis 1:27).

‘For this reason a man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, so that they become one flesh’ (Genesis 2:24).

‘Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ’ (Ephesians 5:21).

John Sentamu writes:

God created man and woman for partnership, mutual comfort and joy. And, for Christians, marriage is exemplified by Jesus Christ’s loving and nurturing relationship with his Church.

Jasvinder’s disturbing story reveals a picture of marriage that is far removed from this ideal. She endures shame and disgrace, and painful alienation from her family before being lifted up and restored to a life in which she can rediscover the honour and dignity given to human beings by God in his creation.

Through years of perseverance and hope, God gave her strength, not only to forgive those who had rejected her, but to reach out with help to others who were suffering in the same way.

Jasvinder Sanghera’s story:

I first learned I was promised to be married when I came home from school and my mother showed me a photograph of a man I didn’t know and told me he was to be my husband. I was fourteen years old and my parents had agreed this marriage six years earlier.

I hadn’t been expecting it, but I understood something of what my mother was telling me because I’d watched the same thing happen to my older sisters. At age fifteen my sisters went to India and came back as someone’s wife. That was how it was in our community, but on returning my sisters didn’t seem happy, and I didn’t want that life for myself. I wanted to do my exams and go to college. I didn’t want to marry a stranger and I told my parents so.

A year later the wedding preparations began. A wedding dress was purchased and people started to come to our house to visit the bride-to-be, who was me. That was when I really protested. ‘I’m not marrying a stranger,’ I insisted, ‘I want to finish school.’

I didn’t go back to school after that. My parents shut me in a room with a padlock on the outside of the door and told me that I couldn’t leave until I agreed to the marriage. I was kept prisoner by my parents for what seemed like weeks, but it was probably in reality about ten days. Even when I attempted suicide it didn’t make any difference to my situation. No one sought medical attention for me, my parents just walked me up and down, giving me lots of coffee to drink. In addition to the physical abuse, my mother used a lot of emotional blackmail to try to sway me to her way of thinking. She told me that if I didn’t marry this man, then the shame would cause my father to have a heart attack and it would be my fault. In the end I agreed to the marriage, but it was purely as a plan to escape. Whatever happened, I was determined that I wouldn’t marry this stranger.

My mother didn’t view the man as a stranger. Her and my father’s union had been a similar arrangement when she was a teenager. My father came to the UK in the late 1950s from a very rural village in the Punjab of India, and my mother joined him much later. Our household operated on a system of honour, and one way of bringing dishonour onto the family was to question a marriage. Speaking outside of the family was also a cause of shame, so we never spoke about what was happening and the abuse remained hidden for years.

I don’t know why I was the daughter to question what was happening. Perhaps it was because since I was small I was always told that I was different. I was the only one of my parents’ eight children to be born in a hospital, I was born upside down, and I have a mole on my right cheek that my family constantly tried to rub off. Now, in planning to escape, I was doing something more different than any of my community could imagine.

Once I’d agreed to the marriage, I was allowed to move around the house, and while I couldn’t go back to school I was allowed to visit a friend from an Asian family who lived nearby. I begged her brother to help me, and one day I left my parents a note and we ran away together to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, sleeping in parks and washing in public conveniences. My parents reported me missing to the police, but thankfully when an officer caught up with me he believed my story. I explained that I was being forced to marry against my will and the policeman agreed that he wouldn’t tell my parents where I was, so long as I made a call to let them know I was safe.

My mother answered the phone. At the time I thought that by running away, my parents would understand just how upset I was at the idea of this marriage and would begin to see my side. I explained how much I was missing everyone and how I wanted to come home, but I didn’t want to marry this stranger.

My mother said: ‘You either come home and marry who we say or from this day forward you are dead in our eyes.’ It took a long time for those words to sink in. I thought that she was just angry, but she reinforced it by adding, ‘You have shamed and dishonoured the family.’ As if that wasn’t enough, my mother told me that I’d never amount to anything, that I’d be rolling around the streets forever, I’d become a prostitute and I’d give birth to a daughter who would do the same to me as I’d done to her – then I’d know how it feels.

I heard her words, but part of me still believed that in time my family would come round to my way of thinking. Regardless of the abuse that was happening, this was still my family, the people I had grown up with, who I loved dearly, and I kept on hoping that one day they would accept me back into their lives. I made phone calls home for three years, but the abuse and rejection was always the same. My only solace came when two of my sisters began to talk to me in secret.

When I was 18 years old I visited Whitley Bay and saw the sea for the first time. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, if this is on the planet, what else is there?’ Standing on the beach gave me a great sense of hope that there was so much more I could do with my life. I’d made my choice and I had to get on with it. So, I set myself up as a market trader, married the boy who had helped me to run away and gave birth to our daughter the following year. Having a child of my own made me realise what it meant to love someone unconditionally. I wished I could have shared that joy with my family, but even knowing they had another grandchild didn’t change my parents’ view.

I started to visit my sister, Rabina who was a mother now too. I would meet her in secret and she would tell me how unhappy she was in her marriage. I tried to persuade her to leave. ‘That’s easy for you to say because you don’t have to think about honour,’ she told me. She was right. I’d already been cast out, so those things weren’t at the forefront of my mind anymore. Then, one day a woman came to my market stall and told me I should ring home because something had happened.

My mother answered the phone. ‘It’s Rabina, she died. She committed suicide. She set herself on fire and she’s dead.’ I wanted to go to the house, but I was reminded of my position of shame and dishonour. After persistence I was allowed to visit after dark when no one would see me.

After the funeral we were not allowed to speak of Rabina again. I was so angry that the concept of honour was being put before a human life – that it was better for Rabina to take her life than to leave her husband and bring dishonour on the family. All these years I’d carried around this label of being a horrible, mean person who had done terrible things to my family. I began to realise that there was nothing unworthy about me – I was a victim. My anger over-rode the fear I once had, and I decided that I wasn’t going to let them treat me like this anymore. I’d done nothing wrong, there was no reason for me to hide, so I moved back to my hometown of Derby.

My mother’s health deteriorated rapidly after Rabina’s death, although she never spoke of her. When she became terminally ill we had a secret relationship, always on my mother’s terms. I wasn’t allowed to visit her at the hospice when the rest of the family was there, and would have to visit in the middle of the night. When the nurses told me that her death was imminent, my mother asked me to leave. I refused and the family arrived to see me by her bed. They were all shocked – our dirty little secret was out. ‘Just leave it now,’ my mother said, and her last words were, ‘Rabina, I’m coming to you.’

My mother’s death wasn’t the end of my family differences. I was still shamed. My marriage broke down; having no family to turn to for support, I was vulnerable to unhealthy relationships and married again in haste. The marriage was unhappy but I stayed because I had nowhere else to go. In my heart I kept telling myself, this is not my life, this can’t be my life. I knew that I needed to get a job to enable me to protect my children and bring them up to have a better life, but with no qualifications what could I do? I decided to get back into education and nervously signed up with the local college.

I was 27-years-old before I read a book, but once I started the classes I realised that I could learn, that I did have intelligence, and that I wasn’t worthless. In that same year I set up Karma Nirvana, to help other women speak about their experiences of forced marriage. The name means peace and enlightenment, because if you have choices then you can achieve a sense of peace. I didn’t think about it as a charity at this time, I just believed that the silence had to be broken. I was teaching keep fit classes and when women would talk to me afterwards about their personal lives I’d tell them about this organisation that could help. When I say organisation, it was just a phone in my front room, but it was something.

I’d always carried a sense that I wasn’t clever, but once I passed my A levels I began to gain confidence and went on to study social and cultural studies at university. In my final year my marriage broke down irretrievably while I was pregnant with my son. It wasn’t easy, but with the support of two women who became great friends I managed to finish my studies and graduated with a first class honours degree. I was the only one of my family to graduate and I sent my father an invitation to the ceremony, at which I was asked to give the student vote of thanks. He never came. I remember looking out from the stage and seeing my three children. It was the first time I’d spoken in front of an audience and as I started talking the script I’d written didn’t seem the right thing to say anymore. Instead, I thanked my father and mother, because if it wasn’t for them then I wouldn’t be standing in Britain being able to be educated. For the first time, I felt no anger towards them. Regardless of what had happened, I felt immensely grateful to my parents for taking the decision to travel all that way and make the UK their home. I started to speak about my personal experience and the words kept coming. When I finished the audience all rose to their feet clapping, and I realised that there is power in simply saying what you think and feel.

I had been angry for so long, but it was time to let all the hurt go. At the same time I decided to let God in too, to learn more about forgiveness and to embrace the good things in my life, like my children, my health and my gift for being able to speak about my experiences and having people who would listen. For a long time doors would close in my face and people didn’t want to hear what I had to say because I was clouded by resentment and rejection. I realised that my anger had been holding me back. I stopped grieving the loss of my family and began to put my energy into Karma Nirvana. I believed in it completely. Volunteers would ask me, ‘Do victims ever call the helpline?’ and I’d reply, ‘They will one day, trust me.’ It took four years to get our first call, but to date we have assisted 30,000 victims on our helpline, more victims are speaking out, and this year forced marriage became a criminal offence in the UK.

When my father died, unbeknown to me, he made me an executor of his will. I was the only one in the family who had been disowned. I was the only one made to feel unworthy, and yet here was my father entrusting me with his will. After his death I went into his house for the first time. In the corner of his bedroom, my graduation photograph was hanging on the wall. I remember sending it to him, but never knowing if he’d received it because I didn’t get a reply. Seeing that photograph framed, in a place where my father would have looked on it every day, gave me a sense that, although he could never tell me when he was alive, my father thought I was a good person.

2 ‘The Lord has forgiven me’

‘God did not send his Son into the world to judge the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him’ (John 3:17).

John Sentamu writes:

God sent his only Son Jesus into this world, not to judge or condemn us, but so that we might be saved. We are given the chance to draw closer to God, in the midst of whatever troubles we face. God is always ready to forgive but it can take real courage to trust in that forgiveness and start again with God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and with others.

Sometimes we can all fail to miss the point of an exercise. We don’t listen properly to the instructions or feel that we know best. We can start off on the wrong foot which sets us back or we set out in entirely the wrong direction and follow the wrong path. Trying to put things right can seem an impossible task, and finding where to start becomes a real challenge.

Working out what is expected of us or what God’s plan is for each of us is a lifetime’s passion and taking the first step is always the hardest.

Jim’s story is about taking his first steps, gaining confidence and trust. In following Jesus Christ, he found love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. What are you waiting for?

Jim Race’s story:

There are many different routes I could take into York. I don’t know why this particular Monday morning I chose to walk along High Petergate, because it was slightly out of my way, or why I chose to go back to talk to two men I’d decided were nutcases, but I’m pleased I did.

At the time I was lost in every sense. In the past when everything was going wrong I had always managed to pick myself up and build up what I’d lost, but this time for whatever reason I realised that I didn’t have that same verve any more.

Walking along I noticed a cage outside St Michael le Belfrey Church. Well, you couldn’t miss it really because inside it were two men dressed in bright orange coveralls. ‘Lunatics!’ I thought, crossing the road to avoid them. ‘York is full of lunatics.’

I carried on walking, telling myself how awful it was that there were so many nutcases on the streets these days, but something inside me was inquisitive. I had to go back and ask what they were doing.

The young men told me their names were Luke and Gav, and they were living in this small cage for a week without any provisions, knowing that the Lord would provide.

‘People find themselves trapped in all sorts of situations,’ said Luke, ‘sometimes through no fault of their own, but we believe that Jesus can bring freedom in any situation.’

This explanation didn’t leave me thinking that they were any less strange. ‘What happens if nobody brings you any food?’ I asked.

‘Oh, we know people will,’ said Gav.

I couldn’t get my head around what they were saying. Someone from the church asked if I’d like a chair and brought me a cup of tea. So, there I was sitting comfortably, drinking my tea and talking to these two chaps who had nothing. When I stood up to leave I thought I’d been there for about 20 minutes. It turned out that I’d been talking to them for twoand-a-half hours. I can’t remember what we talked about, I just remember finding it so refreshing that they weren’t asking for anything from me.

I didn’t have much to give at the time. In the past I’d been a professional sportsman, a successful publican and hotelier, running a chain of six pubs. I didn’t recognise that man in myself anymore. I felt old. I’d had a series of heart attacks which had forced me to retire on health grounds. I’d lost my relationship, I’d lost my home, and I was living in a hostel for the homeless. The situation was entirely my fault. I’d been married three times and divorced three times. I’d built businesses and I’d lost businesses. I seemed to have a self-destruct button that I had a habit of pressing when things were going well. It was always when I got to the pinnacle of anything that I’d go into a deep depression, which felt as if someone had thrown a wet blanket on me and I couldn’t see anything. I wouldn’t wash, I wouldn’t take phone calls, I didn’t even want to get out of bed. I never wanted to kill myself, but at times like that I wanted to go to sleep and not wake up.

The old saying that you always hurt the ones you love was very true in my case. I’d lash out at my nearest and dearest, anyone who was trying to lift me out of the depression. In the end that kind of behaviour drives people away and it did. Usually something would happen, like the real threat of losing my business, to jolt me out of the depression. It would take me months, maybe a year to build the business back up again. This time, however, I felt I’d pressed the destruct button one time too many, because I couldn’t get my life back.

The next day I walked back into York along the same route to see if Gav and Luke were still there. Seeing that they were, I bought them each a pasty and a hot coffee. I couldn’t get over the fact that they would just know someone would bring them food and drink, yet every day I took something for them, so I guess they were right. Whether they really needed anything from me didn’t matter, because I wanted to give them something. After a couple of days I started to get my own chair out of the church and would sit outside the cage chatting for I don’t know how long.

I did that every day for a week, whatever the weather. Indeed the final day was a washout, but I walked into town in the wind and rain nonetheless to be there to see Gav and Luke finally freed. Again we chatted and they invited me to go on an Alpha course at the church. ‘Oh, yes, that would be marvellous,’ I said, but typical of me at that time, I didn’t show up.

A few weeks later I bumped into Gav on the street. ‘What happened? You didn’t come,’ he said.

‘No, I was busy,’ I replied and went on my way. Within a few minutes I’d bumped into Luke.

‘Hey, you never came and we were really looking forward to seeing you,’ he said.

Again I made my excuses, ‘I couldn’t. I’ve just moved into a new flat and I had to get it sorted because I’ve got nothing for it.’

It was true that I had just moved into a new flat, because the following week I’d been offered a housing association property. The flat was unfurnished, but I didn’t let anyone know that I had nothing to furnish it with. I just wanted a home so I accepted the flat straight away without question. I told myself that because I was moving house I was too busy to go on the Alpha course. It was a convenient excuse. The truth was, I wasn’t sure that the course was for me. I thought it would be full of people reading the Bible and praying – that wasn’t for me. I didn’t understand what it was all about. I had been to church before, but it was such a long time ago. My grandfather was a verger and I always went to Sunday School as a young child. Then between the ages of 11 and 13 I joined the church cricket team. I enjoyed that, but it was a summer sport so once the season had finished, my season at church ended too. When I became too old for the youth cricket team I stopped going to church. There had been no place for Christ in the last 40 years of my life. I didn’t pray then and I didn’t know how to pray now. If I went along to the Alpha course I was sure that I would make a fool of myself. So, I didn’t go and I stayed in the flat, on my own.

‘What’s your address?’ Luke asked. ‘We can help you with some furniture. We’ll pick you up on Sunday morning and take you to church if you like?’

I didn’t know why these lads would be bothered with someone like me but I gave Luke my address and on Sunday morning, just as he said, he arrived. He saw I had nothing in the flat, but he didn’t say anything. We drove to church and to my surprise I found that I enjoyed it.

The following week I went back, and then the next, and the next. People at church helped me find furniture for my flat. I started getting involved in church life and became one of the welcoming team on the door. I found the fellowship wonderful. I loved the people, I loved the chance to worship and the chance to ask for forgiveness for everything I’d done. I wanted forgiveness, but I couldn’t believe it was possible, not for me, not after everything I’d done in my life and the way I’d treated people. I couldn’t believe that the Lord would want me after that.

I told the vicar how I was feeling. ‘Just keep faith,’ he said. ‘The Lord wants you. The Lord forgives everything.’

One Sunday evening, part of the service was about God meeting us where we are and using us as we are. A rush like an electric current ran through my body as I realised, for the first time, that I could be forgiven and that I was forgiven. I felt completely cleansed and it was the most wonderful feeling. I held my arms in the air, singing the hymns at the top of my lungs. This is it, I thought. This is the start of a new life. The Lord has forgiven me and I’ve forgiven anyone who has ever done anything to me. Everything I’ve done in the past is written off and I don’t need to worry about it. I don’t even need to think about it. I can just concentrate on helping as many people as I can.

That Christmas I invited a couple of lads from the hostel to my flat for dinner and asked if one of the chaps on the church welcoming team would like to join us.

‘If you’re cooking for two, I’d rather us cook for all the homeless if we can,’ he said.

‘Ok,’ I said. ‘If you can get the premises, I’ll do the cooking.’ We were given permission to use the church hall, but apart from ourselves we had no other resources and we certainly didn’t have any money to buy the food we’d need. So, we prayed about it and to our surprise people started donating money.