“I have a pretty short attention span, but I couldn’t put this book down. The Rabbi and the CEO is carefully researched and fun to read, and it’s one of those extremely rare books that give mere mortals real access to great management. If you lead anything, do yourself a favor: Get this book. It offers a kind of leadership power that is all too often missing in boardrooms and that you simply won’t find elsewhere.”

—ALI VELSHI

CNN Senior Business Correspondent and host of Your $$$$$

“The Rabbi and the CEO provides an insightful “lighthouse” to navigate the dynamic world of leadership and management in the 21st century. More than ever in today’s challenging environment, authentic leadership and a strong moral compass are paramount, and this book provides strong insight and tools into these critical areas for success.”

—DR. MARTIN CROSS

CEO, Novartis-Australia

“As the CEO of UJA-Federation, I find myself speaking to audiences all over the Jewish community about leadership, values and the “vision deficit” in our organizations and communities. All our institutions can benefit from better management and leadership. The Rabbi and the CEO is engaging, packed with insights, rich in perspectives, and yes, wisdom. The writing keeps the reader (or at least this reader) absorbed. I recommend this volume to all those, both in the Jewish community and far beyond, who must lead today. Kol ha’kavod.”

—DR. JOHN RUSKAY

Executive Vice President and CEO, UJA

“In an age where anything goes, and unfortunately almost anything does, it’s refreshing to rediscover a familiar anchor. The leadership wisdom contained here is timeless, powerful and actionable—just what you’d expect when you combine a Rabbi and a CEO!”

—SCOTT A. SNOOK

Professor of Organizational Behavior, Harvard Business School

“In my 30 years as the leader of The Hunger Project, I have faced all the challenges any 21st-century leader will ever face, from mobilizing a truly global movement to fostering alignment on a nearly impossible vision, from empowering leaders at all levels of society to keeping the organization true to its mission under intensely adverse circumstances. I am pleased that today’s and tomorrow’s leaders will have The Rabbi and the CEO as a guide at their side. This compelling work of scholarship and humanity helps leaders tackle seemingly insurmountable challenges. Above all, it is a manual for that most elusive of leadership skills: unleashing the human spirit.”

—JOAN HOLMES

Founding President, The Hunger Project;

Member, UN Millenium Project Hunger Task Force

“It has been said that you can tell the worth of a person’s religion not by how he acts in synagogue on Saturday or in church on Sunday, but by what he does in business Monday through Friday. In The Rabbi and the CEO, a highly creative application of the Ten Commandments, Dr. Zweifel and Rabbi Raskin have a great deal to teach us and each other about living both a godly life and, in every way, a successful one.”

—RABBI JOSEPH TELUSHKIN

Author of Jewish Literacy and A Code of Jewish Ethics

“As leaders in business and in life, we need breakthroughs in how we think and act for the uncharted territory of our future. This book provokes and inspires us to build this leadership capacity in ourselves and others. Act now.”

—ANNE GRISWOLD

Director Organizational Effectiveness,

LifeScan, a Johnson & Johnson company

“An invaluable moral compass for today’s turbulent times. Buy this book; sell your kidneys if you have to.”

—RABBI SIMCHA WEINSTEIN

Author of Up, Up and Oy Vey and Shtick Shift

“This is powerful stuff. In turbulent times, more and more managers, in Japan and elsewhere, draw inspiration from the Bible. I have built my company on these principles and tools, from checking my own blind spots and letting go of control, to effective communication with my people and global citizenship, to turning breakdowns into breakthroughs. The Rabbi and the CEO makes the difference between a good company and a great company.”

—MIKIO UEKUSA

Chairman, Akebono Corporation, Japan

“Do we have any true leaders today, or are we all followers? In response to our current crisis of leadership, Dr. Thomas D. Zweifel and Rabbi Aaron L. Raskin, in a fascinating collaboration, have created an important and uplifting book—a profound and practical guide for both active and aspiring leaders. Based on the timeless Ten Commandments, The Rabbi and the CEO offers a timely model for leaders of the 21st Century.”

—SIMON JACOBSON

Author of Toward a Meaningful Life

“This book has the merits of relevance and reverence. It offers relevant, pragmatic and sound business guidelines inspired and informed by profound reverence for the primary spiritual sources of the Jewish faith. I recommend it to all who care about the ethical values of our ‘globalized’ business world.”

—RABBI DR. TZVI HERSH WEINREB

Executive Vice President, Union of Orthodox Jewish

Congregations of America

“The CEO and the Rabbi advise simple changes that have traction and generate results. It is an awesome project, it hits home, and I can apply it. Imperative reading for every CEO.”

—LAWRENCE OBSTFELD

CEO, Image Navigation Ltd.

“Authors Raskin and Zweifel have provided us with a sorely needed exposition of the new leadership model based on the template of creation, the Torah—the Jewish wisdom teachings. Its core principles and central pillars provide a powerful light at the end of the darkened tunnel of the twenty-first century. The authors’ prowess as social commentators is matched by scholarly underpinnings allowing their words to ring true.

Leadership holds the key to the ‘new world.’ But leadership is no longer the domain of those in positions of power. Today, in a world where view and opinion has been democratized through the Internet, leadership devolves on each and every one of us. Each one of us holds the key to the global future. The authors have done us a great service in putting that key into our hands. Dare we unlock the door that Torah provides to create a much better way? If we continue on the current path of egoism and insecurity, ‘that way madness lies.’”

—RABBI LAIBL WOLF

Australia; Author of Practical Kabbalah

“The Rabbi and the CEO couldn’t be more timely. As the financial industry is being rocked by a tsunami, this book provides an anchor in the rough seas of volatile global markets and corruption scandals. More personally, the financial and career successes I have enjoyed have all come from living the lessons in this book. Just read it. It’s the highest-leverage investment you could make in your future.”

—MICHAEL S. BROMBERG

Senior Vice President, Global Wealth Management

“Judaism’s ideal is to join wisdom and wealth. A dynamic CEO and a dynamite Rabbi join to teach timeless principles to advance your career, cultivate your soul, and succeed spiritually and materially.”

—MAGGID YITZHAK BUXBAUM

Author of The Light and Fire of the Baal Shem Tov

“Zweifel and Raskin take the Ten Commandments off the synagogue wall and put them where they belong—in the marketplace. There are valuable lessons here for today’s leaders and decision makers.”

—PROFESSOR ARI L. GOLDMAN

Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism;

Author of The Search for God at Harvard

“Dr. Zweifel and Rabbi Raskin have provided a workable roadmap to understanding one of our greatest needs and mysteries—what is the meaning and impact of true leadership and how is it achieved? In my field of venture capital, they provide great vision and direction. ‘Venture,5’ in its broadest sense, is a new, freer way—the innovative changes that free all of us to enjoy new ways of living. ‘Capital,’ in its truest sense, is our inner resources. The Rabbi and the CEO demonstrates that the greatest source of capital comes not from our bank accounts, stock portfolios or corner offices, but from within each of us. After reading and rereading the book, I’ve learned so much, and I can’t wait to impart it to venturers of every type.”

—GEORGE WEISS

Founder and CEO, Beechtree Capital

“The inherited wisdom of Jewish tradition offers us guidance that is at once spiritual and practical. The Rabbi and the CEO offers the gift of this direction to 21st century leaders of all stripes. The book speaks to managers who want access to the principles and practices that have served leaders ever since Moses. It also provides state-of-the-art executive management tools for contemporary American religious leaders. Read it and you will gain the influence that comes from profound insight.”

—RABBI TSVI BLANCHARD, PH.D.

Director of Organizational Development, CLAL

“Moral values are the basis for the human race to prevail, and ethics are the fundamentals for leadership in business or any other activity. It’s only natural to find a common denominator that links leaders in history and in business life. The Rabbi and the CEO is a very interesting effort to reflect the meaning of the Ten Commandments in the economic content of today. Exciting reading.”

—DOV TADMOR

Chairman, Aviv Venture Capital

“Seamlessly bringing together ancient wisdom and 21st-century case studies, The Rabbi and the CEO’s impressive scope of inquiry and fresh ideas offers valuable insights for anyone interested in leadership. In the face of the leadership crisis in almost every walk of modern life, the book charts a road map to leadership at once effective and ethical, through a process looking both inward and outward. This book makes you stop and think, and then offers you tools to move forward.”

—OREN GROSS

Irving Younger Professor of Law and Director, Institute for

International Legal & Security Studies, University of Minnesota

“In Jewish prayer, the Torah is referred to as ‘instructions for living.’ For every dimension of life, the Torah contains timeless—and priceless— wisdom. This book brings the light of Jewish wisdom to people who carry particularly great responsibility in life: leaders.”

—SHIMON APISDORF

Author of Beyond Survival, Rosh Hashanah Yom Kippur Survival Kit and Kosher for the Clueless but Curious

“As a senior executive who works at the intersection of Judaism and management, I found The Rabbi and the CEO an inspiring and indis-pensible guide and reference. It offers a perfect mix of ancient Jewish philosophy and state-of-the-art leadership tools—a mix that will give leaders an edge in today’s complex ethical and global environment. Every nonprofit manager, indeed all leaders who are committed to something bigger than themselves, should read this book.”

—SCOTT RICHMAN

Executive Director, Dor Chadash

A confronting (while highly entertaining) read, The Rabbi and the CEO summarizes the costs we pay when leadership is insufficient. The authors invite us to explore the possibility of our own leadership and, at the same time, bring contemporary meaning to the Ten Commandments for those who choose to lead.

—MEL TOOMEY

Scholar in Residence, Master of Arts in Organizational Leadership

at The Graduate Institute

The CEO and the Rabbi bring their unique and original insights into the Bible, and its leadership principles, to bear on today’s leadership responsibilities. Readers will be inspired to apply the new dimensions of self-knowledge gained from the authors.

—MALCOLM ELVEY

Chairman of the Audit Committee, The Children’s Place Retail Stores Ltd.

“The Rabbi and the CEO: the 10 Commandments for 21st Century Leaders is a transparent title for a book that preaches transparency in everyday and corporate life. Rabbi Raskin and Dr. Zweifel make you look at the Ten Commandments in a new light. The Commandments are the foundation of Judeo-Christian religions and ethics, and religious in nature. The authors manage to approach each Commandment in a new light without denigrating its source and nature. Through a review of each Commandment and its core principles the book is a practical guide to personal growth, finding an ethical base, and developing one’s ability to lead others in the private and public sectors regardless of one’s personal religious beliefs.”

—STEVEN Z. MOSTOFSKY

President, Young Israel

“It’s about time someone did what these authors are doing: remind people that the distance from Mt. Sinai to Wall Street can be far or it can be very near. Reminding humans of what their limitations ought to be requires courage. Hoping that people will heed the words on these pages is an act of faith.”

—HANK SHEINKOPF

Political strategist and CNN contributor

“Dr. Zweifel and Rabbi Raskin offer the reader a true convergence of worlds. Their work is revelatory in the best sense—a union of the ancient and the modern, the sum of heaven and earth, a compilation of style and substance. Here in brief is a latter-day decalogue of usable wisdom, a Mount Sinai for the 21st century.”

—MICHAEL SKAKUN

Author of On Burning Ground: A Son’s Memoir

and former consultant, Holocaust Memorial Council

“In my work with chief executives around the world I have found that the principles and practices in The Rabbi and the CEO have timeless applicability both for those clients and inside my own company. The insights presented by Zweifel and Raskin been very helpful to me in building a viable global business that operates ethically and from clear principles. Regardless of your religious beliefs, the lessons they present are universal and continue to be timely. This is a book executives should read and share with their co-workers.”

—JAY GREENSPAN

Founder, JMJ Associates

Copyright © 2008 by Thomas D. Zweifel and Rabbi Aaron L. Raskin

This edition published by SelectBooks, Inc.

For information address SelectBooks, Inc., New York, N.Y. 10003.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-59079-150-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zweifel, Thomas D., 1962-

The rabbi and the CEO : the 10 commandments for 21st-century leaders / Thomas D. Zweifel & Aaron L. Raskin (Rabbi) ; foreword by Ali Velshi. – 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59079-150-9 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. Leadership. 2. Leadership--Religious aspects--Judaism. I. Raskin, Aaron L., 1967- II. Title.

HD57.7.Z94 2008

658.4'092--dc22

2007052083

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The great and wise

Rabbi Simcha Bunam of Przysucha

once said to his students:

“I wanted to write a book, it should be called Adam,

and in it should be the whole human being.

But then I thought of not writing this book.”

We were not so wise.

–the Authors

Contents

Foreword

Why the 10 Commandments for 21st Century Leaders?

Acknowledgments

Prologue: Leadership Self-Assessment

Commandment I

Out of Egypt: Beyond the Limits

Tool 1.1 The Five Fallacies of Fuzzy Thinking

Tool 1.2 The Five Types of Power

Commandment II

No Idols: Authentic Vision

Tool 2.1 Unfinished Business

Tool 2.2 Co-Creating Vision

Tool 2.3 Restoring Vision in Five Steps

Commandment III

Don’t Speak in Vain: Leading Through Language

Tool 3.1 Effective Feedback in Six Steps

Tool 3.2 From Kvetching to Commitment

Tool 3.3 Text and Subtexts

Commandment IV

Keep the Sabbath: The Power of No

Tool 4.1 Managing from Priorities

Tool 4.2 Weeding Out

Commandment V

Respect Father and Mother: Appreciation is Power

Tool 5.1 Drain vs. Leading/Learning

Commandment VI

Don’t Kill: Anger Management

Tool 6.1 Cool It With Your Boss

Tool 6.2 Back to the Source of Anger

Tool 6.3 Institutionalizing Anger Management

Commandment VII

No Adultery: Walk the Talk

Tool 7.1 The Four Ethical Dilemmas

Commandment VIII

Don’t Steal: The Business of Giving Back

Tool 8.1 The Raul Julia Model—Investing from the Future

Commandment IX

No False Witness: Breakdown to Breakthrough

Tool 9.1 From Lemons to Lemonade in Three Steps

Commandment X

Don’t Covet: In Their Shoes

Tool 10.1 Theater—Acting Out the Other Side

Tool 10.2 Decoding Another Mindset: The Onion Model

Endnotes

Appendix

The Ten Commandments

The Seven Universal Laws of Noah

The Thirteen Principles of Faith

Further Reading

Index

The Authors

Other Books by the Authors

Resources for Leaders

Foreword

Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.

—G.K. Chesterton

During my years at CNN, I’ve spoken to and worked with countless business leaders. Interviewing them always made me wonder: What makes a truly great leader? Is it something you’re born with? Or can leadership be taught? Can someone be coached into leadership, like so many books I see at airport bookshops proclaim? Is leadership a function of the situation (Would Churchill have risen to greatness without facing the menace of Hitler? Remember, Churchill wasn’t reelected after winning World War II)? Or is leadership a function of culture, with certain cultures breeding leaders better than others?

The authors of The Rabbi and the CEO have arrived at an innovative and powerful answer. Blending time-honored traditions with cutting-edge management methods, this book produces an amalgam that offers leaders (and leaders-in-waiting) a kind of power that’s often missing in boardrooms. Steeped in the rich, ancient tradition of Jewish thought, this book makes the timeless wisdom of the ages directly relevant to today’s business leaders.

The unique synergy comes from an unusual partnership: the prominent Rabbi Aaron Raskin, eloquent spokesman for Judaism, and author of Letters of Light; and Dr. Thomas D. Zweifel, a CEO and leadership professor and consultant in his own right, and the author of four previous books on leadership and people power, including Communicate or Die and Culture Clash.

Why Judaism? Don’t other traditions offer equally profound and rich principles and insightful stories? Yes, all roads lead to Rome, and there are countless ways to reveal essential truth. On the anniversary of a death, for example, Catholics offer a memorial mass; Muslims might read the 36th chapter of the Qur’an; Protestants might gather to sing hymns like the early twentieth-century song “Tell Mother I’ll Be There”; Hindus might cook the favorite meal of the deceased, bring it to the temple and serve it to the priest; Buddhists might burn special counterfeit money known as ghost money to repay the dead for their kindness; the Haida Indians of the American Northwest might set out a meal and burn the whole table; and Jews say the kadish prayer on the yahrzeit of their dead every year. Most everyone, it seems, lights a candle.

But Jews are not universally called the People of the Book by accident. Their book, the Torah—the five books of Moses, also called the Pentateuch from the Greek word for “five”; or, by gentiles, the Old Testament—is a sheer boundless fount of stories about leaders and their moral dilemmas, from Abraham to Noah, from Eve to Sarah, from Moses to David. The Hebrew Bible is chock-full of leaders’ trials, tribulations, and triumphs. And if leadership is about freeing yourself from the shackles of the past and achieving a desired future, the Jews undertook one of the boldest collective emancipations of all time when they left Egypt. The Hebrew word for Egypt is mitzrayim, which means “the narrows.” A core objective of the Torah is to remove us from our own Egypt: to help us transcend our limitations, unleash our indomitable human spirit, and be all we can be. That is what true leadership is all about: enabling people to be themselves, take charge, and fulfill their highest aspirations.

But the Rabbi and the CEO did not stop there. They found that when they married teachings from Torah and Talmud with modern leadership models, the combination yielded powerful insights into today’s leadership challenges—trials that would have given even great leaders like Churchill or Kennedy a headache—and useful instruments for tackling any issue that might confront a twenty-first-century manager. How do you keep your moral compass when you face an ethical dilemma? How do you restore the big picture in the clutter of the day-to-day? How do you communicate effectively to mobilize highly mobile knowledge workers for results? How do you manage outsourcing, off-shoring, or virtual teams through remote empowerment across borders? How do you minimize wasteful chatter in meetings, and turn complaints into commitments? How do you keep your eye on the ball, not merely on what’s urgent, but on what’s important? How do you deal with adversaries who sabotage your efforts? And the skill that distinguishes leaders from non-leaders: How do you turn a bitter lemon into sweet lemonade?

To answer these questions, The Rabbi and the CEO takes you into the lives of leaders across history, Jewish and non-Jewish, to distill principles and practices based on the Ten Commandments and Jewish teachings. You will go into the wilderness to meet the Jewish leader mentioned most often in both the Bible and the Qur’an: Moses. You will see how Moses became a leader despite his stammer (much like Gandhi in our time), parted the waters of the Red Sea for his people, pioneered a system of delegation (thanks to his father-in-law Jethro, the world’s first “management consultant”), and helped his followers keep their vision until they reached the Promised Land.

The result: The Rabbi and the CEO arms you with the tools you need to be an ethical and effective leader—now and in the future. And since these tools have stood the test of time, they are built to last, for managers of all stripes. Just as the ad once said, “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s rye bread,” leaders don’t have to be Jewish to appreciate, and apply, Jewish teachings. These principles work: They make for the leadership DNA that has led a tiny group (some 0.2 percent of the world population and 2 percent of Americans) to provide 17 percent of all Nobel laureates in physiology and medicine, 11 percent of physics Nobelists, and 10 percent of U.S. senators.

It’s simple: When leaders veer from these teachings, they fail. Great leaders, on the other hand, whether they are Moses or Mandela, transcend themselves. They reach beyond their own narrow interests and embrace the well-being of the many around them. Moses Maimonides, the great twelfth-century scholar in Egypt, wrote that the world is like a scale: one side is 50 percent good, the other 50 percent bad. Any action can tip the scale either to one side or the other. One selfless executive decision can bring salvation, peace, and harmony to the whole world. Churchill put it this way: “You make a living by what you get; but you make a life by what you give.” If you truly dare, you can change the world for good. So I hope that people everywhere will enjoy this carefully researched and fun-to-read book as thoroughly as I did, and turn its powerful lessons into practice as they build a better world.

ALI VELSHI

Anchor & Senior Business Correspondent, CNN

New York City, August 2008

Why the Ten Commandments for 21st Century Leaders?

Again and again Someone in the crowd wakes up.

He has no ground in the crowd And he emerges according to much broader laws.

He carries strange customs with him and demands room for bold gestures.

The future speaks ruthlessly through him.

—Rainer Maria Rilke (Über Kunst, 1899)

This book would probably not have come into being were it not for a perfectly clear day in September 2001, an Indian-summer morning when the sky was deep blue. I (the CEO) was sitting on the Brooklyn Promenade—alone except for a few runners and dog walkers—and reading Michel Houellebecq’s Les Particules Élémentaires when I looked up at 8:46 a.m. and saw something I had never seen before: A plane hit the World Trade Center. Smoke and millions of tiny metallic glitters were in the air; a light wind swept them toward me. The glitters turned out to be countless papers, documents flying across the East River. One of them was a page from a civil law book, blackened on all four sides. Another was a FedEx envelope with a contract that someone had just signed a few minutes earlier.

About a half-hour later another plane flew in from Staten Island, right over the Statue of Liberty. It flew low and accelerated head-on toward those of us now gathered at the Promenade. It banked like a fighter plane, its dark underbelly visible—a terrifying sight that you usually see only in war zones or in movies. Suddenly the plane ducked behind a skyscraper, and a moment later disappeared into the South Tower. By this time there were about a dozen people watching, speechless and transfixed. I called as many people as I could on my mobile phone, but got through only to my parents’ answering machine in Sydney before my phone went dead. Then I saw one tower collapse, then the other. My knees gave in; I staggered to a bench, sat down, and wept. It was hard to breathe.

Like so many others, the only productive thing I could think of doing was to donate blood. It seemed a drop in the bucket. That day of calamity, and the days and years following it, exposed the most pressing issue of our time: Leadership is in a crisis. The Pentagon, FBI, and CIA were all ill-equipped for terrorist attacks or even for reading the writing on the wall. But the crisis affects organizations in all sectors: government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and international organizations whose leaders struggle with mega-issues like economic volatility, climate change, poverty, or AIDS that transcend national and organizational boundaries. And not least, the crisis is shaking the private sector. When Enron and Andersen, Worldcom and Swissair all collapsed within a year of 9/11, they were just harbingers of things to come. Today, despite an abundance of leadership books (a search at a popular online retailer yielded 191,530 hits), the leadership crisis continues unabated. Look at the big challenges facing companies today: Turbulent change such as a U.S. sub-prime mortgage crisis that threatened to plunge the economy into a recession and led Bear Stearns to fall from a record high of $171 a share in January 2007 to near bankruptcy (in 2008, JP Morgan Chase, with heavy lifting by the Federal Reserve, agreed to buy the venerable investment bank for $10 a share); unrelenting pressure for results and corruption born of greed; post-merger pains and a deteriorating labor market ever since the 2000 dot-com crash; culture clashes and threats from India and China; lack of strategy alignment, loss of morale, and brain drain. What do all these issues have in common? Our (the Rabbi’s and the CEO’s) answer is, they all need leadership. Call us biased, but we see the lack of twenty-first century leadership—leadership that can rise to meet the unprecedented challenges of our time—as the lynchpin issue that underlies all the others. It was of times like these that the economist and philosopher Kenneth Boulding said: “The greatest need for leadership is in the dark. ... It is when the system is changing so rapidly... that old prescriptions and old wisdoms can only lead to catastrophe and leadership is necessary to call people to the very strangeness of the new world being born.”

Why do we say crisis (and we take the word, much like the Chinese character for crisis, as meaning “danger” combined with “opportunity”)? Two reasons: for one, ethical decision-making seems to have taken a long vacation. For too many executives, the game has become about looking good: fudging the numbers in the relentless pursuit of elusive and fickle shareholders. Ken Lay, Jeff Skilling and Andrew Fastow of Enron were only the most visible cases. Witness Maurice Greenberg, the imperial ex-chief of AIG who was subpoenaed and ousted by his own board after a forty-year tenure; Gary Winnick of Global Crossing and Bernie Ebbers of WorldCom; Lloyd Silverstein and other senior managers who lied in a federal inquiry into Computer Associates’ accounting; Adelphia and Tyco; Boeing and Putnam; HealthSouth and Prudential; Parmalat and the Bank of Japan; Martha Stewart and Samuel Israel, and—surprise—Greenberg’s own son Jeffrey at Marsh McLennan.

Leaders like Steve Case of AOL or Bob Nardelli of Home Depot, once unassailable, have lost much of their luster. And business is not alone; the pandemic of deceit has infected the public and nonprofit sectors. The disgraced former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer was one of the more egregious examples of a state official who failed to walk his talk, gaining national attention as “sheriff of New York” who prosecuted businesses and prostitution rings while being a client of one high-priced sex ring himself. Corruption scandals have tainted more elected officials than we could list here, not to speak of autocratic leaders in the Middle East, or those who were not above poisoning Viktor Yushchenko to derail his campaign for the Ukrainian presidency. A U.S. federal judge presiding over a price-fixing case involving Monsanto conveniently failed to disclose to the parties in the case that in 1997-98 he himself had been a Monsanto lawyer in another case about some of the same issues—a clear conflict of interest.

Senior officials in the Catholic Church and the military have covered up sexual misconduct by priests and soldiers with conspiracies of silence, sometimes for decades. EU and UN bureaucrats have been charged with embezzling millions of euros or dollars. The son of Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary-general who supposedly embodied the moral conscience of the world community, stood accused of colluding with former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein to steal billions from the UN’s oil-for-food program.1

And if you think senior officials are the only ones who cheat, think again. Corruption is wherever the money is. Remember how after Hurricane Katrina tore through the Gulf region, FEMA needed days to mobilize? Another group was on the scene much faster: profiteers. In Mississippi, a couple from Indiana rolled into Jackson and began selling generators out of a horse trailer for as much as $2,600 (they usually cost $700). In Texas, some budget motels charged refugees from Louisiana up to $300 a night—six times the normal rate.2

Even the world of sports is riddled with corruption; world records and gold medals have become tainted with suspicions of doping. In the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the U.S. athlete Jerome Young was a gold medalist in the 4x400 meter relays; in 2003 he became the 400-meter world champion; in 2004 he was suspended because of repeated use of illicit substances. And while baseball pitcher Roger Clemens, a seven-time Cy Young Award winner with 354 wins under his belt, issued indignant—and unconvincing—denials during his congressional testimony and in a 60 Minutes interview in early 2008 (“never happened,” he kept snapping at interviewer Mike Wallace), he was widely believed to have been injected with steroids and growth hormones by his former personal trainer, who admitted as much. Far from acting alone, athletes like Young and Clemens conspire with accomplices. “Now we recognize that not only the athlete but veritable teams are involved in the cheating: scientists, doctors, pharma marketers,” explained Richard Pound, head of the World Anti-Doping Agency. “One can speak of organized crime...It taught me that people lie. When they’re caught, they lie.”3

Governments have sought to punish and deter ethical lapses. In the United States, after the corporate and accounting scandals of Enron, Tyco International, Adelphia, Peregrine Systems and Worldcom when the collapse of these companies’ share prices cost investors billions of dollars and shook public confidence in the securities markets, the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (in short SarbOx or SOx, after its sponsors, Sen. Paul Sarbanes, Democrat of Maryland, and Rep. Michael G. Oxley, Republican of Ohio); the 2002 federal law established stricter standards for all U.S. public company boards, management, and public accounting firms and set up an oversight agency. In 2007, China went further when it executed the corrupt head of its State Food and Drug Administration. But the real solution is not legal. Yes, better rules or policing might enhance accountability and transparency, but “There won’t be quick fixes,” admitted Robert Reynolds, chief operating officer of Fidelity Investments, with $906 billion under management at the world’s largest fund manager. (He should know: In late 2003, the state of Massachusetts subpoenaed a salesperson from his own company for improper dealings.) Without morality, without leaders at all levels who can tackle ethical dilemmas, more regulation will not work. Since countless managers have lost their moral compass in the rough seas of globalization and deregulated markets, corporate America and organizations the world over must begin an internal process of renewal.

This book aims to help leaders at all levels find that compass again. The Rabbi and the CEO is about a fundamental change that’s needed: change from within. It’s a type of change that is hardly fashionable; boasting of outward successes is still much more popular. Loud and bossy leaders grab the headlines and thrust themselves into the limelight; think Donald Trump and The Apprentice. Quiet leaders are crowded out, lost in the background. The egomaniacs and their scandals are much more fun to watch and read about. Many of these so-called leaders lack the essentials, the fundamentals on which sound leadership is based, and which breed lasting success.

But ethics is only one aspect of the twin crisis of leadership. The other stems from an entirely different quarter: The old leadership model is bankrupt. Why? Because throughout history, leadership was scarce. The vast majority of people never asked themselves what to do. People were subjects; they were told what to do, and their work was dictated either by the nature of their work—for a peasant or a crafts-man—or by the lord of the manor. Although Descartes and other later thinkers made a dent with the idea that humans could use their own powers of reason, even the Enlightenment did not fully transform the deeply ingrained culture: people did pretty much what they were told by their parents, superiors, or rulers. The Industrial Revolution that followed in the next century only compounded this mechanistic view; Frederick Taylor’s efficiency “improvements” were the culmination of human beings as cogs in a wheel. Even in the 1950s and 1960s, the new knowledge workers (referred to as organization men at the time) looked to their company’s personnel department to plan their careers for them. But starting with the late 1960s, the game changed. Young men and women asked, What do I want to do?4 Several waves of democratization gave more and more people the idea that they had rights, they had a voice.

Then, in the 1990s, came the Internet. Google and Wikipedia put knowledge at people’s fingertips with the click of a mouse. Now Skype and LinkedIn connect people across the world for free or next to nothing. Blogs have leveled the field of journalism. In the last century, consumers chose among a few TV channels and magazines; by 2007 there were were hundreds of cable channels on TV and 70 million blogs on the World Wide Web. MySpace and YouTube, where 65,000 videos are posted daily, have democratized entertainment and give anyone a shot at being a musician or movie director. Thanks to Macs and Web 2.0, you too can be an industrial designer in the new design democracy.5 End-users know exactly what they want from the products they buy—more so than manufacturers—and so-called lead users are often on the forefront of innovation and product development, from software to high-performance windsurfing equipment.6 It is no different in healthcare, where patients have stopped blindly trusting their doctors and instead demand answers and choice—something unthinkable a generation ago, when doctors were thought to be omniscient demigods whose judgment they never dared question.

Churchill was famous for saying that the higher you rise, the more clearly you see the big picture of vision and strategy. (He also said, somewhat presciently, that the higher the ape climbs, the more you can see of his bottom.) But is that still true today, when the receptionist or the front-line salesperson talks to customers every day and may have as much insight into the market as top managers and board members? Even the military has recognized that soldiers on the ground in Sadr City or Seoul have often more access to local strategic intelligence than the commanders at headquarters and need to take part in strategic decision-making. In complex environments, top-down strategy or leadership is obsolete. The good news is that leadership is no longer confined to the realm of the select few; it has become a public good. More people than ever before in history can now aspire to the mantle of leadership.

That is not to say that they do, or that the leadership craft has become any easier; quite the opposite. In fact people’s desire to be in charge has diminished. Take chief executives. Leslie Gaines Ross, chief knowledge officer at Burson-Marsteller, surveyed executives at Fortune 1000 companies and asked how many of them craved being the head honcho. In 2001, 27 percent responded that they had no interest in being CEO; by 2005 that number had jumped to 64 percent in North America and 60 percent in Europe. Ross’ explanation: “You take a lot of risk today in choosing the top job.”7 Indeed, in 2005, a record 1,322 chief executives left the corner office, both voluntarily and not; in 2006, departures (or firings, as the case may be) included the bosses of some of America’s best-known companies: Ford Motor, Home Depot, Kraft Foods, Nike, Pfizer, RadioShack, UnitedHealth, et al. Sure, many CEOs have their own reasons for leaving. But according to the study, intense global competition, an impatient Wall Street pushing for instant results, and regulators on the war-path all contribute to corner office angst. Many CEOs feel under siege.

Why? Because this new leadership landscape—globalization and democratization, flattening organizational hierarchies and virtual teams, outsourcing and offshoring, the Internet and ubiquitous media—turns leadership into a more complex challenge than perhaps ever before. Even the twentieth century’s greatest leaders might have had a hard time leading in the twenty-first. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s debilitating polio would be all over the Internet, had he ever become chief executive. John F. Kennedy’s chronic affairs would haunt him while he faced not one but multiple enemies. And Winston Churchill would constantly be shown on YouTube for his battle with the bottle. Not to speak of business leaders like Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Watson, or Alfred Nobel: They would come under near-constant attack from shareholders bemoaning short-term losses or from the media criticizing their products. More than ever, leadership is in the hot seat, forcing leaders to stay centered in ways that past leaders never had to.

What are the critical competencies leaders must master now? Take a cue from Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and one of the great business leaders and strategists of our time. When Buffett announced to shareholders in 2007 that he planned to hire a younger person (or several) to understudy him in managing Berkshire’s investments, he did not mention financial savvy or technical skills or even strategic thinking. Qualified candidates, Buffett noted, must possess “independent thinking, emotional stability, and a keen understanding of both human and institutional behavior.”8

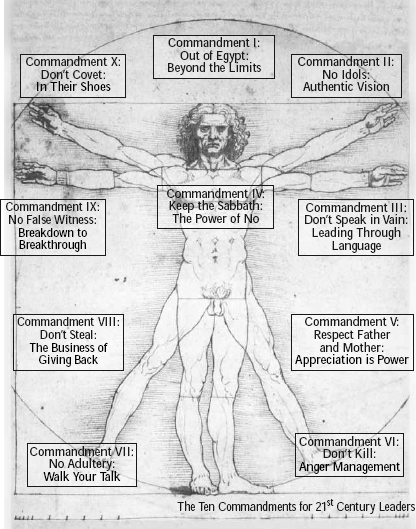

No question: Leaders of a new kind are called for. But how can such a transformation be brought about? More than two hundred years ago, Michael Faraday took two different fields—physics and chemistry— and married them to create a new phenomenon: electricity. To transcend today’s leadership crisis, we (the CEO and the Rabbi) propose to do the same with the two fields of Judaism and leadership. We found that marrying the two makes something new possible: a new type of leadership. Just like the ten vessels (sefirot, literally, enumerations) through which God created the world according to the ancient Kabbalah, the study of the mystical meanings of the Torah, each of the ten leadership commandments is interconnected with all others; each is a holographic expression, building on all of the other commandments and leading back to them all. Here is a quick overview:

In Commandment One, Out of Egypt, great leaders start by going beyond their comfort zone; they free themselves and unleash the potential of others. In Commandment Two, No Idols, leaders must build an authentic vision that is not based on idols or external expectations, but is truly their own. Commandment Three, Don’t Speak In Vain, shows how to lead through language, how leaders inspire others to act on their vision through a specific type of speaking and listening.

Commandment Four, Keep the Sabbath, is about how transcendent leaders from Moses to Mandela had the courage to prioritize, say no to demands and circumstances, and take time out to reflect and contem-plate. Commandment Five, Respect Father and Mother, shows how leaders use appreciation as a key management tool; they see the importance of each person and each detail to the overall strategy. In Commandment Six, Don’t Kill, powerful leaders regulate their anger and channel their emotions into productive energy.

Commandment Seven, No Adultery, is about the source of power for leaders: not their corner office, not their title, not even their authority, but their integrity. They walk their talk and tackle ethical dilemmas. Commandment Eight, Don’t Steal, is about how leaders catalyze— embody, even—the future by the way they invest themselves. In Commandment Nine, No False Witness, the greatest leaders are not afraid to give bad news; instead of being stopped by adversity, they harness breakdowns into breakthroughs. Finally, in Commandment Ten, Don’t Covet, global leaders, especially in the twenty-first century, must put themselves in the shoes of their clients, competitors, and even enemies.

These commandments’ principles and practices are so fundamental that many managers might overlook them in the rush to show the external, seemingly important characteristics of leaders. But they are the stuff twenty-first century leaders are made of. (In fact we hope readers come to use The Rabbi and the CEO as a reference they will keep dipping into for continuous guidance.)

And potent stuff they are indeed. Like fire, leadership can be used to destroy or to build. We assume that you will use the tools in this book for good. Tremendous damage has been done in the world because some have been compelled to put their leadership skills to dishonest or even evil ends. Fueled by greed, intolerance, and revenge, these so-called leaders have perpetrated wars, famine, and commercial or environmental ruin, and have wrought havoc on their companies or whole nations. Under the best leaders, however, people have triumphed over impossible circumstances; fought and won against tyranny and oppression; overcome poverty, hunger, ignorance, and disease; and distinguished within the collective consciousness such notions as equality, freedom, and dignity. In business, they have innovated, made the impossible possible and doable, and mobilized to achieve breakthrough results. (As Herb Kelleher, the former leader of Southwest Airlines, put it recently, “a humanistic approach to business can pay dividends—and believe me, I’m not off my meds!”9) The choice is yours. Use your power wisely.

T.D.Z. AND A.R.

New York City, June 2008

Acknowledgments

Without 9/11 the CEO and the Rabbi might have never met or crafted this book. (From now on, throughout the book, whenever we mention “the CEO” and don’t specify further, we mean co-author Thomas D. Zweifel; whenever we say “the Rabbi” without adding a name, we mean co-author Aaron L. Raskin. Maybe our roles will be reversed in another lifetime or two; but that is the way it is for now.)

The day after, both of us went back to mourn the thousands of victims and the loss of the world’s innocence (including our own). The CEO sat there with countless others, holding a candle and staring into the smoking, dusty void where the twin towers had stood only the day before, when the Rabbi walked up to him with his full regalia, black hat and beard and tefillin10—and, because the Jewish New Year was fast approaching, a shofar in one hand and a tiny bottle of honey in the other. He asked, “Are you Jewish?” The CEO looked up; he had never met the Rabbi before, and usually would have ignored a stranger or waived him away. But on that somber day, something made him say, “Yes, I am.” The Rabbi asked, “Okay, would you like to put on tefillin?” The CEO answered, “I’ve never done this before, but today of all days seems like a perfect day to start.” So the two of us, with hundreds of people watching, tied the tefillin on the CEO’s left arm and his head, and said the prayer, the Rabbi slowly pronouncing a few holy words at a time, the CEO repeating them haltingly. On that day, a great friendship was forged. Soon the two became collaborators and fellow leaders who coach each other: the Rabbi helps the CEO step back from business and life challenges and make sense of them; the CEO assists the Rabbi in setting strategic direction and tackling leadership challenges.

We thank the readers of our previous books who believed in our ideas. We are grateful to the members of Congregation B’nai Avraham in Brooklyn Heights, led by Stephen Rosen, founder and president, for their generosity and human spirit; Rabbi Simcha Weinstein for his dynamism and ideas; Rabbi Samuel Weintraub and the Kane Street Synagogue in Brooklyn’s Cobble Hill and Rabbi Harold Swiss of the Little Synagogue for first opening the door; Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh and Rabbi Dov Ber Pinson for paving the road less traveled; Michael and Sarah Behrman, Jay Greenspan, Elyakeem Kinstlinger, Samuel Mann, Allan Scherr, Motti Seligson, Sam Shnider, Tom Steinberg, and Michael Weinberger for useful insights and inspiring conversations.

We thank Julie Schwartzman and Alexander Reisz for their unvarnished feedback; we thank Lynne Glasner and Nancy Sugihara for their meticulous editing; Kenichi Sugihara for his creative marketing ideas; and Kenzi Sugihara for his unflappable wisdom in the stormy seas of publishing.

We thank the CEO’s clients—top managers, entrepreneurs, government and UN officials, and military officers—who have turned the Ten Commandments into results for a quarter-century. We are indebted to the CEO’s friends and Swiss Consulting advisers Lawrence Flynn, Florian Goldberg, Peter Spang, and Nick Wolfson for generously sharing concepts and best practices; and to Richard Klass and Lark Bryner for their stories and jokes.

We thank Mina Kim and Yariv Nornberg for research on Perrier; Abril Alcala-Padilla, Jamie Ho, Mihyun Park, Ned Peterson, and Chunyu Yu for research on General Electric; Robin J. Böhringer and Simon Koch for research on Ford; and the CEO’s more than five hundred leadership students so far at Columbia University, St. Gallen Business School and Haute Ecole de Gestion Fribourg (both Switzerland), Sydney University, and the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (Israel), who researched case studies and helped bring out ideas in this book through challenging dialogue.

We thank our parents and our early teachers and role models Benzion and Bassie Raskin, and Dr. Eva and Dr. Heinz Wicki-Schönberg, who cut the tall grass and showed us what works. We thank Shternie Raskin, a natural leader and manager, for her strategy and intuition from which the Rabbi learned so much, and Yankel, Eliyahu, Mendy, Chaya, and Yehoshua Raskin for encouraging the Rabbi to be a better leader every day. We thank Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe and the Rabbi’s mentor, for setting the highest standards of leadership, and Rabbi Jacob J. Hecht, the Rabbi’s grandfather, for his inspiration and example. We thank the city of Basel, the CEO’s hometown, not only for bringing forth tennis champion Roger Federer, a master of anger management (see Commandment 6 “Don’t Kill”), but also for hosting the First Zionist World Congress in 1897 that was attended by the CEO’s great-grandfather, Rabbi David Strauss of Zurich. After the Congress, Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, was to write, “To summarize the Basel Congress in one sentence—which I shall be careful not to pronounce publicly—it is this: At Basel I founded the Jewish state.”11