Copyright © 2016 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Brand

One Montgomery Street, Suite 1200, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594— www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Permission is given for individual classroom teachers to reproduce the pages and illustrations for classroom use. Reproduction of these materials for an entire school system is strictly forbidden.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Readers should be aware that Internet websites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available at:

978-1-118-70198-0 (Paperback)

978-1-118-70196-6 (ePub)

978-1-118-70200-0 (ePDF)

Cover image: © ayzek/iStockphoto

Cover design: Wiley

Numerous experts on classroom observations provided invaluable insights for this book. We greatly appreciate the contributions of: Colleen Callahan (Rhode Island Federation of Teachers); Sheila Cashman (Chicago Public Schools); Melissa Denton, Sandra Forand, and Lauren Matlach (Rhode Island Department of Education); Dennis Dotterer (South Carolina Teacher Advancement Program); Paul Hegre (Minneapolis Public Schools); Sara Heyburn (Tennessee State Board of Education); Dawn Krusemark (American Federation of Teachers); Tyler Livingston and Renee Ringold (Minnesota Department of Education); Catherine McClellan (Clowder Consulting LLC); Stephanie Aberger Shultz (District of Columbia Public Schools); David Steele (retired from Hillsborough County Public Schools, Florida); and Jonathan Stewart (Partnerships to Uplift Communities [PUC] Schools). Consultant Mark Toner provided significant editorial support. Additional design and editorial guidance came from KSA-Plus Communications. Many thanks also to Pamela Oakes (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) for her highly valued coordination and project management assistance. Finally, we are grateful to the staff at the New York office of the Brunswick Group for so graciously hosting our many work sessions as we wrestled this book's content into shape.

Left to Right: Steven L. Holtzman, Steve Cantrell, Cynthia M. Tocci, Jess Wood, Jilliam N. Joe, and Jeff Archer

Jeff Archer is president of Knowledge Design Partners, a communications and knowledge management consulting business with a focus on school change issues. A former writer and editor at Education Week, he has worked extensively with the MET project to translate the implications of its research for practitioners.

Steve Cantrell, a former middle school teacher, is a senior program officer in the K-12 Education division at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He has played a leading role in guiding the foundation's investments in innovative research and development focused on improving teaching and learning. He codirected the MET project's groundbreaking study of teacher evaluation methods.

Steven L. Holtzman is a senior research data analyst in the Data Analysis and Research Technologies group at ETS. He served as research lead on the MET project's video-scoring project and several other MET studies.

Jilliam N. Joe runs a research and assessment consulting business, Measure by Design. She is a former research scientist in the Teaching, Learning, and Cognitive Sciences group at ETS. At ETS, she provided psychometric and design support for the MET video-scoring project, and research and implementation direction for the Teachscape Focus observer training and certification system.

Cynthia M. Tocci, a former middle school teacher, spent more than 20 years at ETS, where she worked as an executive director in research. She was the senior content lead for Danielson's Framework for Teaching during the MET video-scoring project, and for the Teachscape Focus observer training and certification system. Now retired from ETS, she runs a consulting business, Educational Observations.

Jess Wood, a former middle school teacher and instructional coach, led development of an observer training system while at the District of Columbia Public Schools. Now a senior policy advisor at EducationCounsel, a mission-driven policy and strategy organization, she works with states and districts to improve the way we attract, prepare, support, and evaluate educators.

Guided by the belief that every life has equal value, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives. In developing countries, it focuses on improving people's health and giving them the chance to lift themselves out of hunger and extreme poverty. In the United States, it seeks to ensure that all people—especially those with the fewest resources—have access to the opportunities they need to succeed in school and life. Based in Seattle, Washington, the foundation is led by CEO Susan Desmond-Hellmann and Cochair William H. Gates Sr., under the direction of Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett.

The MET project was launched in 2009 as a research partnership of academics, teachers, and education organizations committed to investigating better ways to identify and develop effective teaching. Culminating findings from the project's three-year study were released in 2012. Funding came from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. For more, see www.metproject.org.

Imagine two teachers—Mr. Smith and Ms. Lopez—who work in different districts, and who have very different views on classroom observation. Mr. Smith is skeptical of observations, and for good reason. From his conversations with colleagues about being observed by different evaluators, he suspects the ratings they get have more to do with who does the observing than with the quality of the teaching. Moreover, Mr. Smith has never left a post-observation conference with a clear understanding of the reasons for the ratings that he received. Nor does he have any clear ideas of how to improve his ratings. Not surprisingly, he sees little value in observations and has little faith in evaluation.

Ms. Lopez's experience is different. At first, she too was skeptical of classroom observations. She thought they were primarily a mechanism for accountability and was unsure of the criteria. After experiencing several observations by different evaluators, however, her views have changed. The feedback she received clearly explains how what happened in the lesson aligns with the performance levels that are spelled out in the district's observation instrument, which embodies the district's expectations for teaching. Most important, when she sits down for a post-observation conference, she now expects to leave with a concrete plan for improving her teaching practice.

Both scenarios are playing out across the country. In some schools and districts, teachers report getting meaningful feedback from observations. But not in others. Across some districts, observation results appear to be consistent and accurate. But across other districts, the results suggest that teaching is being judged based on different standards, or that evaluation remains a perfunctory exercise in which virtually all teaching is deemed proficient. On the whole, classroom observation today may be better than in the past, when it was based on simple checklists (e.g., “was the lesson objective posted?”), but the quality of implementation clearly remains uneven.

What will it take for all the Mr. Smiths to have the same experience as Ms. Lopez? A big part of the answer is ensuring that observers have the full set of knowledge and skills that quality observation requires. Observation is a highly challenging task. Observers must filter a dynamic and unpredictable scene in the classroom to find the most important indicators of performance, make an accurate record of them, and then apply a set of criteria as intended. Observation is complicated by the fact that, as educators, we've all formulated our own views of what effective teaching looks like, which can lead us to interpret and apply the same criteria differently. We're not used to seeing things through a common lens. Providing observers with instruments and procedures is not enough; they need the opportunity to learn how to use them effectively.

Figure I.1 To Improve Teaching and Learning, Professional Growth Matters Most

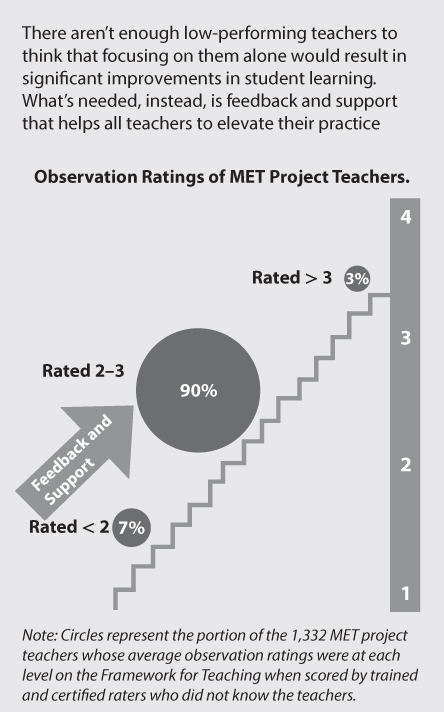

Ensuring that observers can provide accurate and meaningful feedback, in rich conversations with teachers, is essential for improving teaching and learning. Research indicates there aren't enough clearly low-performing teachers to think that focusing on them alone will result in meaningful gains in student achievement. The overall quality of teaching in the vast majority of classrooms—perhaps 90 percent—is near the middle in terms of performance (see Figure I.1). Significant progress in achievement will require that every teacher gets the individualized feedback and support he or she needs to change practice in ways that better promote student learning. Quality observation provides not only that, but also the data that state and district leaders need to evaluate and improve their systemwide supports for better teaching.

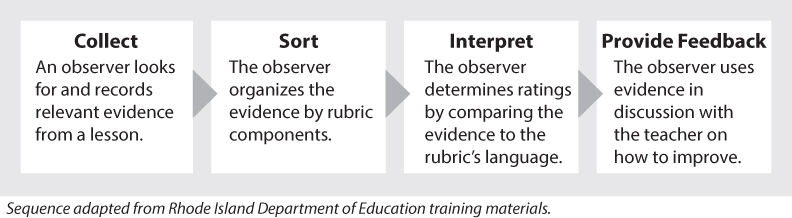

In our field, we've learned a great deal in recent years about what happens in quality observation. Researchers and innovative practitioners have broken down this challenging task into discrete steps, which generally follow the process in Figure I.2. The key ingredient is evidence. Observers collect evidence in the classroom, then use it to rate teaching performance, and refer to it when giving the teacher feedback. The key tool is the observation rubric. How an instrument defines each aspect of teaching and each performance level tells an observer what to look for and how to judge it. By applying clear criteria to objective evidence, different observers can reach the same conclusions about the same lessons.

Figure I.2 The Observation Process

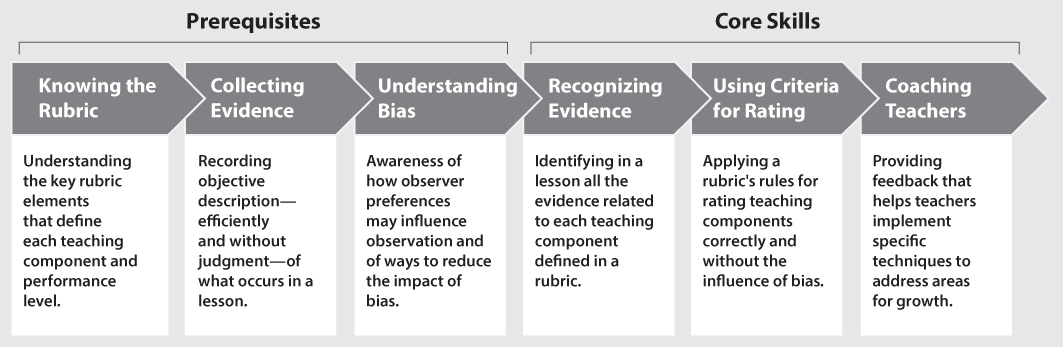

Figure I.3 Observation Knowledge and Skills

But quality observation takes a special set of knowledge and skills (see Figure I.3). To collect evidence, you need to know what evidence is, and what kinds of evidence are relevant. To rate performance, you need to understand the conditions under which each rating is merited. To provide feedback effectively, you need to know how to coach. These competencies build on each other. If you fail to ensure that observers have each of these competencies, or if you try to develop a core skill before developing a prerequisite, you'll frustrate not only your observers but also your overall attempts to provide teachers with accurate and meaningful feedback.

You develop these competencies through repeated modeling and practice. To master a skill, you need to see how it's done effectively, then you need to try it yourself, and then you need feedback that tells you how you did. Much of this modeling and practice will include pre-scored video: videos of teaching that have been reviewed and rated by experts before the examples are used in observer training. Pre-scored video makes visible the thinking behind quality observation and lets trainees compare their own work to examples of good practice in using the observation process. But while pre-scored video is indispensable, an observer-in-training needs a certain amount of foundational knowledge before attempting what experts can do.

In this book we explain how to build, and over time improve, the elements of an observation system that equips all observers to identify and develop effective teaching. It's based on the collective knowledge of key partners in the Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project—which carried out one of the largest-ever studies of classroom observations—and of a community of practitioners at the leading edge of implementing high-quality observations in the field. From this experience, we've unpacked how to build the necessary skills, how to build the capacity to provide quality training, and how to collect and use data to ensure that observations are trustworthy.

The pages that follow speak most directly to those who develop, implement, and improve observation systems, as well as those who prepare, manage, and support individuals who observe and provide feedback to teachers. But observers themselves can deepen their understanding of quality observation and feedback by reviewing the sections in Part III, “Building the Knowledge and Skills for Observation.”

Although we sometimes refer to “evaluators” as the objects of the practices we describe, we use the term broadly to mean anyone whose work entails analyzing and evaluating classroom practice. The knowledge and skills we explain are too important to be limited to administrators and others involved in formal evaluation; peer observers, instructional coaches, and classroom teachers need to know and be able to do what quality observation requires. In addition, while we refer to “states and districts” when describing what to do, and what to avoid, many other actors play a role in developing, managing, and improving an observation system. Our guidance is for anyone whose work affects the quality of observation and feedback.

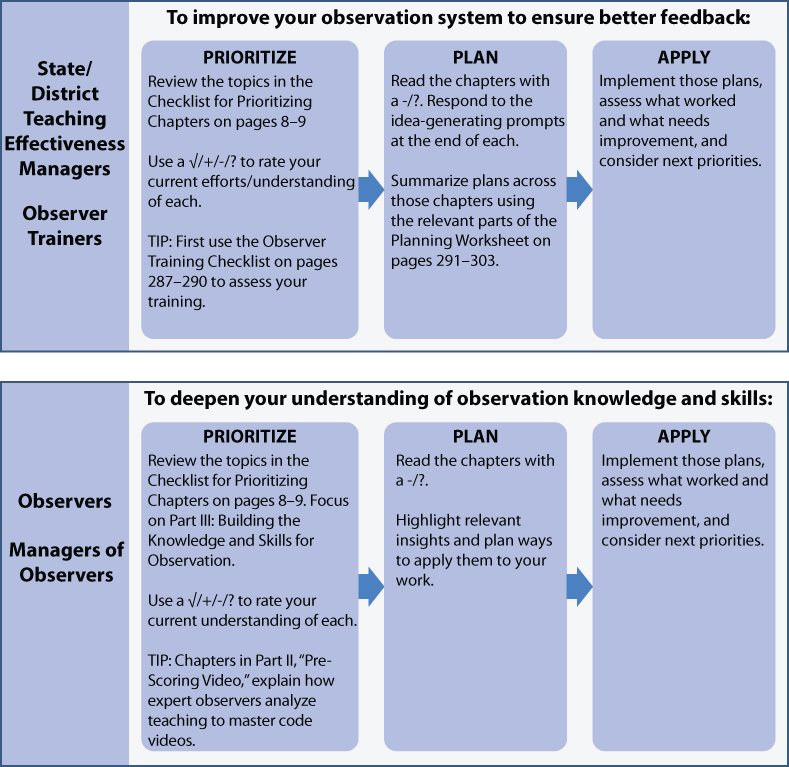

This book is not meant to be used only once or in only one way. Nor must it be read in its entirety. We recognize that observation systems are in different stages of development and exist in widely different contexts. Hence we've organized the content into 19 stand-alone chapters that each address one issue. These may be reviewed in the order that best serves readers' current needs. Figure I.4 presents approaches tailored to different readers and objectives. Each of the 19 chapters includes ideas for getting started, and for improving on existing work. As needs change over time, readers can look back at the material for ways to strengthen what they've put in place, and for ways to address new priorities.

Figure I.4 Ways to Individualize Your Use of This Book

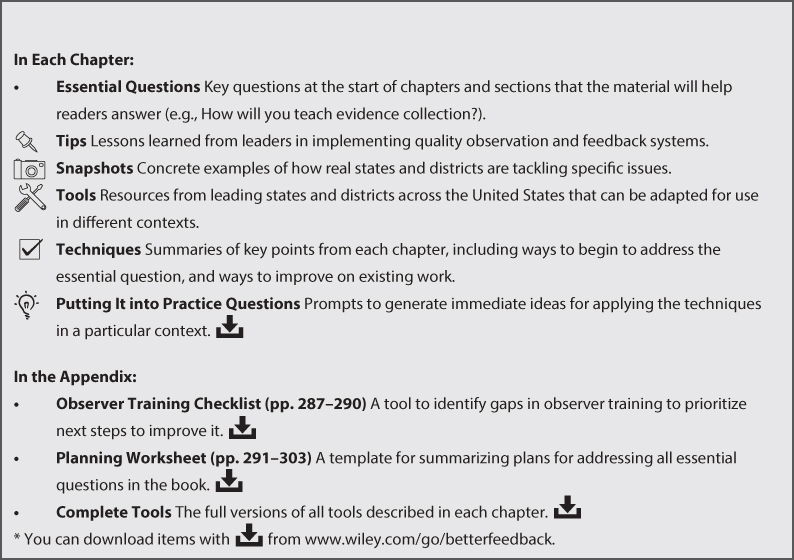

Each chapter includes several features to support readers in turning ideas into action (see Figure I.5). These are to help practitioners answer for themselves how they can build and improve the elements of a quality observation system, by considering what such a system needs to accomplish and how others have developed a set of practices that does so. There's no one right way to do this work in every situation. But there is a body of knowledge that includes proven strategies, tools, and techniques to borrow and adapt for different contexts. Informed by best practice, and their own data, school systems will find their own path to continuous improvement.

Although the material in this book will be of benefit to individuals, observation and feedback are, by their nature, collaborative endeavors. Essentially, they're about people working together to forge a common understanding of goals and how to meet them. In the same spirit, this guide will best support improvement when it grounds discussion, planning, and implementation among colleagues, diverse stakeholders, and critical friends who are willing to share expertise and resources while learning together. Professional learning is most powerful when it happens in a focused professional community.

Ensuring that observers have the necessary knowledge and skills cannot, by itself, guarantee that observations produce better teaching. The practice of observation changes the very notion of what it means to work in the service of student learning. It opens classrooms to peers and instructional leaders, aligns the purpose of evaluation and professional development, and acknowledges that different educators have different strengths and needs. This challenges deep-seated beliefs, mindsets, and cultural norms. Other efforts will be needed to change those beliefs, mindsets, and cultural norms. But working to make sure teachers and observers experience observation as something positive can go a long way toward moving them in the right direction.

Figure I.5 Guide Features for Turning Ideas into Action

Prioritize how you read this book by putting a “✓/+/−/?” next to each chapter based on your current efforts or understanding of each topic.

| Part I: Making the Big Decisions | |

1: 1: |

Building Support for Better Observer Training Creating awareness among stakeholders of how robust training supports accurate and meaningful feedback. |

2: 2: |

Finding Enough Observers Determining how many observers you need, and expanding the pool as needed. |

3: 3: |

Deciding on Training Delivery Methods Determining who should develop and deliver training, and the best modes (online or in person) for your context. |

4: 4: |

Setting Priorities for Observer Training Determining a focus for improving your training in the coming year. |

| Part II: Pre-Scoring Video | |

5: 5: |

Understanding Pre-Scoring Video Understanding the process, products, and value of pre-scoring video. |

6: 6: |

Planning a Pre-Scoring Process Determining a focus for pre-scoring for the coming year. |

7: 7: |

Getting the Right Video to Pre-Score Finding videos of teaching with sufficient quality and content to pre-score. |

8: 8: |

Recruiting and Training Master Coders Identifying expert observers, and preparing them to pre-score video. |

9: 9: |

Ensuring Quality of Pre-Scoring Using quality control checks and data for continual improvement of your pre-scoring process. |

| Part III: Building the Knowledge and Skills for Observation | |

10: 10: |

Knowing the Rubric Understanding the key rubric elements that define each teaching component and performance level. |

11: 11: |

Collecting Evidence Recording objective description—efficiently and without judgment—of what occurs in a lesson. |

12: 12: |

Understanding Bias Understanding how observer preferences may influence observation, and of ways to reduce their impact. |

13: 13: |

Recognizing Evidence Identifying in a lesson all the evidence related to each teaching component defined in a rubric. |

14: 14: |

Using Criteria for Rating Applying a rubric's rules for rating teaching components correctly and without the influence of bias. |

15: 15: |

Coaching Teachers Providing feedback that helps teachers implement specific techniques to address areas for growth. |

16: 16: |

Organizing a Training Program Scheduling and sequencing training into a series of manageable chunks that supports observer success. |

| Part IV: Using Data to Improve Training and Support of Observers | |

17: 17: |

Collecting and Using Data from Training Analyzing information from training to identify areas for improvement. |

18: 18: |

Assessing Observers to Ensure and Improve Quality Determining if observers have sufficient proficiency, and providing additional supports for those who don't. |

19: 19: |

Monitoring Your Observation System Checking if procedures are followed, if observers maintain proficiency, and if teachers get useful feedback. |

![]() This item can be downloaded from www.wiley.com/go/betterfeedback

This item can be downloaded from www.wiley.com/go/betterfeedback

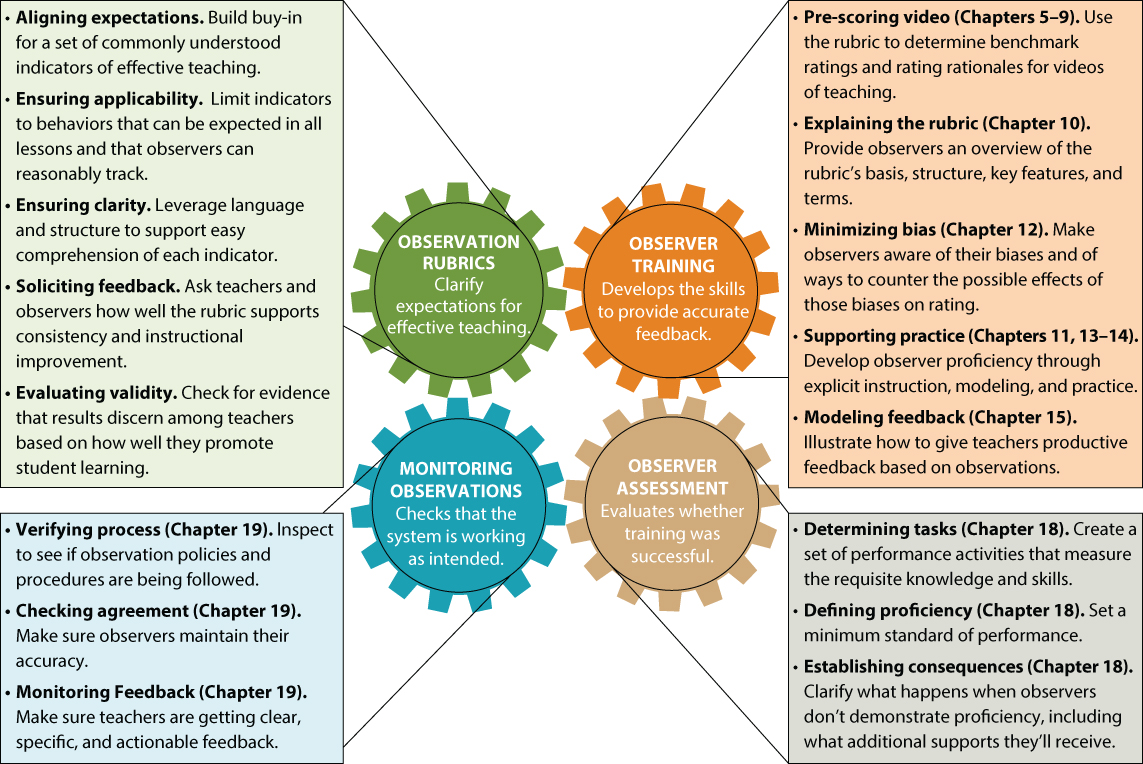

While most of this guide deals with observer training, it's important to understand how all the components of an observation system work together. Often when people talk about observations they refer only to the tools and procedures used in the classroom. But what makes observations trustworthy and effective are a set of components that support and reinforce each other, detailed as follows:

These components reinforce each other and allow for continual improvement. A rubric is the basis for training, but while training observers you may discover parts of the tool that need clarification. Observer assessment builds confidence that observers have mastered the requisite skills, but it also exposes the need for enhancements in training. Monitoring what observers do and produce over time helps in maintaining and improving the quality of all parts of the system.

Figure I.6 Components and Activities in a Trustworthy Observation System (with relevant chapters)

A set of key activities drives each of the four components. For example, a rubric won't work as intended without efforts to ensure that it's clear and manageable for observers. Training won't be successful without pre-scoring video for use in modeling and practicing observation. These activities are shown in Figure I.6.1 Review them and ask yourself to what extent your observation system currently addresses each (for a more detailed assessment of your system's observer training, see the Observer Training Checklist in this book's appendix). This may lead you to zero in on some chapters in this guide before others. Chances are most states and districts are doing some, but not all of these activities.

Looking at this book's contents, you'll see we devote a lot more ink to some components than others. Training—including pre-scoring video—accounts for about 70 percent of this book. Training requires the most resources and the most know-how. It's what equips observers to do what they need to do to provide accurate and meaningful feedback. The other components are essential in large measure because they support the quality of training. Assessment and monitoring provide credible evidence that training is successful—and that the whole system works—as well as the data to continually improve it.

So where are the chapters on rubrics? There aren't any. Because a research-based rubric is the cornerstone of an observation system, most states and districts have already adopted one. The more pressing need is to support observers in using them well. Moreover, rubrics will, and should, evolve as more is known about the best ways to identify and develop effective teaching, and as the expectations for student learning continue to evolve. What isn't going to change is the need to forge a shared understanding of current best practice.

While there are no chapters on rubrics in this guide, you'll see excerpts of rubrics throughout. These come from states, districts, and organizations we know well. These include the Teaching and Learning Framework of the District of Columbia Public Schools; the Framework for Teaching, developed by Charlotte Danielson; and the Standards of Effective Instruction (SOEI), used by Minneapolis Public Schools. Another more recent rubric, developed with a streamlined design, is TNTP Core, created by The New Teacher Project.2

You can find complete versions of these rubrics with a quick web search.

We don't advocate these instruments over others. Indeed, many of the rubrics in use are quite similar, since they're based on similar findings about evaluating effective teaching. At the same time, some of the rubrics we refer to are in the process of being updated based on new research and new student learning objectives. Our goal in referring to specific rubrics is to illustrate the techniques that support a shared understanding of how to use such a tool. Those techniques apply no matter what tool is used.

We need feedback, too. If you've got tools, techniques, or insights for quality observations to share—or comments on the ones in this book—email them to: info@betterfeedback.net.