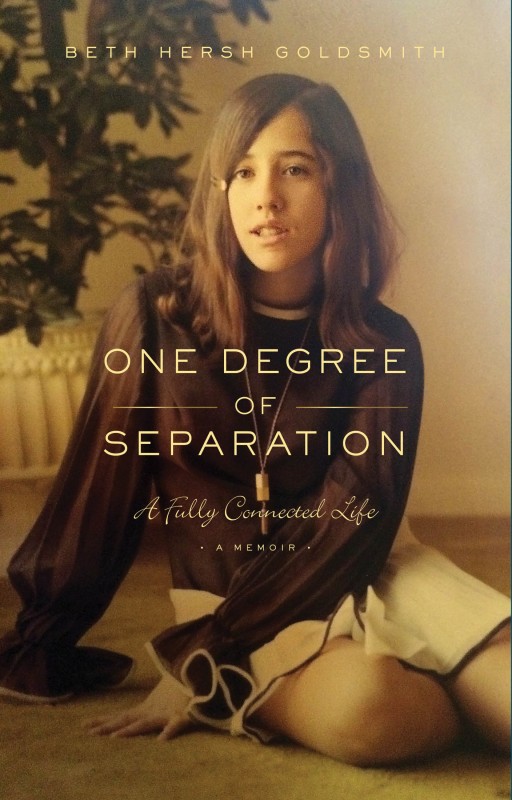

ONE DEGREE OF SEPARATION

ONE DEGREE OF SEPARATION

A Fully Connected Life

• A M E M O I R •

Beth Hersh Goldsmith

WITH TOM FIELDS-MEYER

Copyright © 2015 by Beth Hersh Goldsmith

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be copied, transmitted,

or reproduced without permission.

Designed by Lisa Vega

ISBN 978-1-937650-73-5

Print Edition ISBN: 978-1-937650-72-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016936359

493 SOUTH PLEASANT STREET

AMHERST, MASSACHUSETTS 01002

413.230.3943

SMALLBATCHBOOKS.COM

IN MEMORIAM

Beth Hersh Goldsmith

1957 – 2015

Contents

Contents

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Chapter One: In the Beginning

Chapter Two: The New Girl (with the Broken Arm)

Chapter Three: Berkeley and Jerusalem

Chapter Four: Ms. Hersh Goes to Washington

Chapter Five: L.A. Story

Chapter Six: The Soviet Diet

Chapter Seven: Executive Director

Chapter Eight: The Block Party

Chapter Nine: Lessons from Craig

Chapter Ten: It Takes a Village

Chapter Eleven: It’s Who You Know

Chapter Twelve: It’s a Small World After All

Chapter Thirteen: Family Ties

Chapter Fourteen: We Plan, God Laughs

Epilogue: Saving the World

Afterword

Glossary

Appendix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I HAD A TERRIFIC CHILDHOOD, but there was one missing piece: I did not get to meet any of my grandparents. Both of my parents were orphans by the age of twenty. Not only was this a great loss for my parents, but it also left a serious void in my life. I remember wanting to know at least one of my grandparents, but, alas, it was not to be. The closest I got was adopting other people’s grandparents and establishing special relationships with them.

Not only did I miss out on knowing these special people in my life, I also missed the opportunity to hear stories about their lives—what it was like to grow up in a poor village in Eastern Europe (as my dad’s parents did), or to raise a child in New York City during the Depression (as my mom’s parents did). I knew only that my mom’s mom was an identical twin and that she and her sister were born on the boat that brought them over from Europe. Childbirth is challenging under any circumstances, and I always wondered how the twins survived in steerage. I had many unanswered questions.

I was determined to make sure that my family didn’t experience the same emptiness that I did. I want to share the stories that shaped my upbringing and prepared me for my life and career. I decided there was no better way to do this than to write a memoir.

I had a terrific partner for this project, Tom Fields-Meyer. I met Tom through our close mutual friend, Susan Jacoby Stern. While I am a few years older than Tom, we share many friends in common. Tom has had a career as both a writer and reporter. The reporter in him “fact-checked” many of my stories and he always found the article to substantiate what I said. Many journalists today need Tom fact-checking their stories!

My other fantastic partner on this project is Gordy, my lifelong partner. Gordy told me that he married me for my memory, and I married him because he had better health insurance than I had when we were dating. Gordy questioned my memory on some of my stories, but a quick reminder of the circumstances usually led him to say, “You’re right,” or his most frequently used response: “Yes, dear!” Gordy is one of the best writers I know, and I am forever grateful for his editing and reviewing of the many things I have written over the years.

Noah and Aliza, our wonderful children, provided excellent material for the book because of who they are. They are kind, caring individuals who love to help others and they have been immeasurably helpful to me. Just as my mom worked while we were growing up, I followed in her footsteps and had a career that kept me away from home when our kids got home from school. While at times I felt bad that I did not attend every school or sports program, I also knew that I was able to help people every day with my career, and this was very important to me.

I wanted to lead by example. From the time they were young, our children spent time working in my offices and at my events. I always appreciated their willingness to help me and others. Marlene Sanders, a pioneering television reporter and the mother of CNN commentator Jeffrey Toobin, passed away in July 2015. She beautifully summed up the balance mothers strike between work and family: “You love what you do,” she said, “and loving what you do is a great gift to give your child.”

I am also grateful to my brother, Andrew (whom I have always called Andy), for his suggestions for the book and the stories he remembered—along with the fun adventures we experienced as brother and sister. It takes a village for many endeavors and writing a memoir is one of them.

I have been blessed in so many ways. I had a great childhood, I had an exciting career, which led to extraordinary opportunities, and I have a family that has made me proud beyond my wildest dreams. While it may sound strange to say so, even my cancer has in some ways been a blessing. My rare, asymptomatic cancer has allowed me to continue living my life largely pain-free and to enjoy each and every day that I have been able to fight it. And my early retirement has given me the time to write this book and share my stories.

Winston Churchill famously said: “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.” I feel blessed that in the process of giving, I have been able to create such a rich and full life.

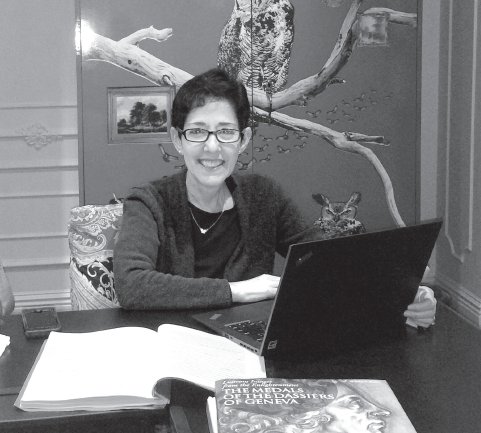

Working on my memoir in Pittsburgh, the week before my March 2015 surgery.

Prologue

“ARE YOU GOING TO GET ME A PLAQUE?”

I THOUGHT I MIGHT DIE on my honeymoon.

There were troubling omens from the beginning. My new husband, Gordy, had planned the entire trip. We had both worked in our jobs for so long and put in such long hours that each of us collected plenty of vacation time, and we wanted to use it to travel to places neither of us had visited. We chose New Zealand, Australia, and Fiji. We would get to spend a month together exploring some of the world’s most beautiful places. What could go wrong?

As it turned out, plenty.

The first sign this would be an eventful trip came early. After a few days exploring Auckland and the country’s North Island we set out in a small propeller plane for the city of Christchurch on the South Island, where we would see Mount Cook, the country’s tallest peak, and enjoy some beautiful countryside. Twenty minutes after takeoff, I noticed the plane was making a sudden turn, reversing its direction. Then the pilot’s voice came over the speakers.

“You may have noticed that we’re turning around,” he said. “One of our passengers missed the flight, so we’re going to swing back to pick him up.”

I thought seriously? Not quite like flying business class to Chicago. Twenty minutes later, we were back on the ground, and I was incredulous. I stopped a flight attendant to inquire. “You fly back and pick up people who miss the plane?” I asked. “They don’t do that in the States.”

“Yeah,” she said, nodding, “things are a little different here.”

That became more apparent the longer we stayed in New Zealand. We were driving our rental car from Christchurch to Dunedin, when Gordy decided to pull off the road to catch a beautiful view of Mount Cook. The shoulder turned out to be a ditch, landing the car at a forty-five-degree angle, with the two left wheels down and the two right wheels in the air. (In Gordy’s defense, overgrown weeds were hiding the ditch from view.) This was long before cell phones, so all we could do was clamber out of the car and wait by the roadside for help.

Fifteen minutes passed before another car came along. It immediately stopped. The driver and passenger were unable to offer any help, but they insisted on staying with us. There, in the middle of nowhere, the four of us chatted while we waited for another passerby. After a while, another car pulled over. Again, the driver couldn’t give us any assistance, but he too waited with us. Two more cars followed, and each driver stopped to express concern and then linger to make sure we weren’t alone. There we stood, on this isolated mountain road, schmoozing with strangers who wouldn’t leave us foreigners by ourselves. For Gordy and me, this was a first.

Finally the fifth vehicle came, a tour bus. The driver used the winch on his front bumper to pull our car out of the ditch, as we watched—alongside our four carloads of new friends. Finally we got back in the car, said farewell to these friendly strangers, and continued on our way.

What Gordy had arranged next was for us to undertake a very strenuous hike. There were several options in the region, but by the time he had made the reservations, his choices were limited. He had scheduled us for a challenging three-day, twenty-mile trek, starting on Christmas Eve, through New Zealand’s Southern Alps on a route known as the Routeburn Track. Normally the guides there led groups of fifteen or twenty hikers. But Christmas week wasn’t a very popular time for trekking, so our party consisted of only the two of us, a young British woman of eighteen, and our guide, a confident Amazonian of a woman who had the body of a Russian Olympic weightlifter.

Gordy and I had trained for the hike, but it turned out to be more rigorous than we anticipated: about seven miles a day of extremely strenuous hills. Since our group was so small, we had just the one guide, and no extra helpers to carry our food or supplies. So we pitched in, which added to the weight of our packs. The first day passed without much difficulty. The second day, we hiked until we got to the cabin where we were to spend the night. Groups would typically share rooms in the cabin (men in one, women in the other), but because there were only four of us, Gordy and I had a room to ourselves.

The guides from other groups joined us for a wonderful Christmas dinner. These incredible athletes easily ran twenty miles to deliver supplies for the feast. So there we were, two Jews enjoying Christmas dinner in our isolated honeymoon hut—complete with bunk beds.

By the third day we were both exhausted and looking forward to a relaxing rest day around the cabin with some short hikes in the area. But then it started to rain. And rain. It turns out the Routeburn is in one of the rainiest spots on earth. We learned that firsthand. We were stuck in a driving rain for twenty-four hours straight: sheets of rain, falling down, nonstop.

On the fourth day, it was time to leave—rain or no rain. By the time we headed out, so much rain had fallen that it had washed away parts of the trail. The path simply disappeared. Later we learned that on nearby trails that day, rescue workers had airlifted hikers by helicopter. But no choppers came to fetch us. We were on our own. And we had little trail to follow, only our guide leading the way. The rain was easing slightly, but still pouring down. I’m only slightly over five feet tall, and there were times when the torrents of water were rushing down so heavily that I simply couldn’t traverse the path our guide was using. There was no way.

Gordy was struggling, too, as the deluge surrounded us. We were still carrying our packs, of course, and at one point he took a step and—whoosh!—he was gone. He had been walking on the side of the hillside path when the ground, saturated with rain, suddenly gave way. Luckily, a strap on his pack got caught on a tree root, so instead of sliding down the hill, he was stuck, staring at my toes. The only things preventing my new husband from falling down the treacherous mountainside were a strip of nylon and the tree root.

The three of us joined forces to lift Gordy to his feet, then continued to make our way, doing our best to escape this disaster area. At one point the water had so inundated the trail that I simply could not cross it, so I turned to Gordy for help. “I can’t lift you on my own,” he told me. “I’m afraid I would lose my grip and you’d be swept away.”

That was when our muscular guide stepped in. In one continuous motion, she lifted me off my feet, hoisted me in the air over the rushing waters, and placed me on solid ground on the other side of a newly formed stream.

As we hiked, I started to notice something: there were plaques affixed to some of the trees and rocks we were passing. Pausing to examine some of them, I realized what they were: memorials to people who had perished on the trail. I turned to Gordy. “If I don’t make it out of here,” I said, smiling, “I just want to know: Are you going to get a plaque for me?”

“Would you stop it?” he said, not appreciating my humor.

“No, I’m serious,” I said, teasing. “Are you going to get me a plaque?”

“I’m not going to discuss that right now, okay?”

“Well, this whole thing was your idea.”

Why start this account of my life with that story? Because it tells so much. About my life with Gordy, which has been a wonderful adventure from Day One. About resilience, and how we both try new things, come what may. About how it is always worth slowing down to help out other people, whether that means returning to the airport to pick up stragglers, waiting at the roadside with stranded travelers, or listening to a coworker or a waiter or a friend. And about finding the strength to get through even the toughest circumstances we encounter.

Thank God, we made it out of the mud of the Routeburn, and Gordy never had to get me a plaque. Instead, I hope that this book, this collection of stories, will serve as my plaque, so that someday my children and their children—and anyone else who cares to—can remember and learn from my adventures (and misadventures), the work I have been privileged to do, the people I have had the honor to know, and the family Gordy and I have been blessed to build. I’ll never have my plaque, so this will have to do.

One more thing about my remarkable husband. Gordy felt so bad about our disastrous adventure on the Routeburn that the next day, when we were back in civilization, he made a few phone calls. “I’m not going to get you a plaque,” he told me, but I’ll do something better.” He phoned ahead and arranged for upgrades for the rest of our trip. So when we went on to Sydney and Melbourne we stayed in five-star hotels. And in Fiji, we enjoyed a wonderful Blue Lagoon cruise through the Fijian islands.

All in all, it was a nice step up from the hut with bunk beds.

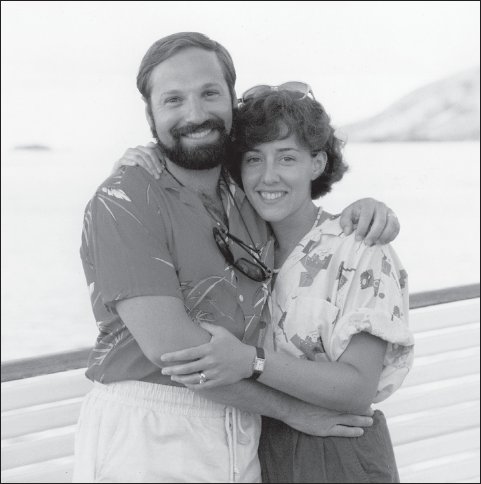

Honeymooning with Gordy in Fiji, January 1986.

Near our home in Oxnard, California, summer 2014.