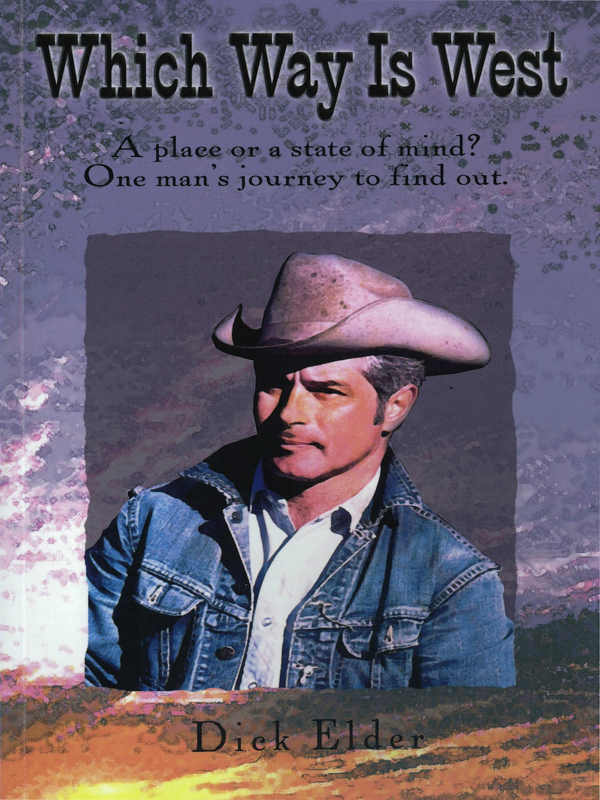

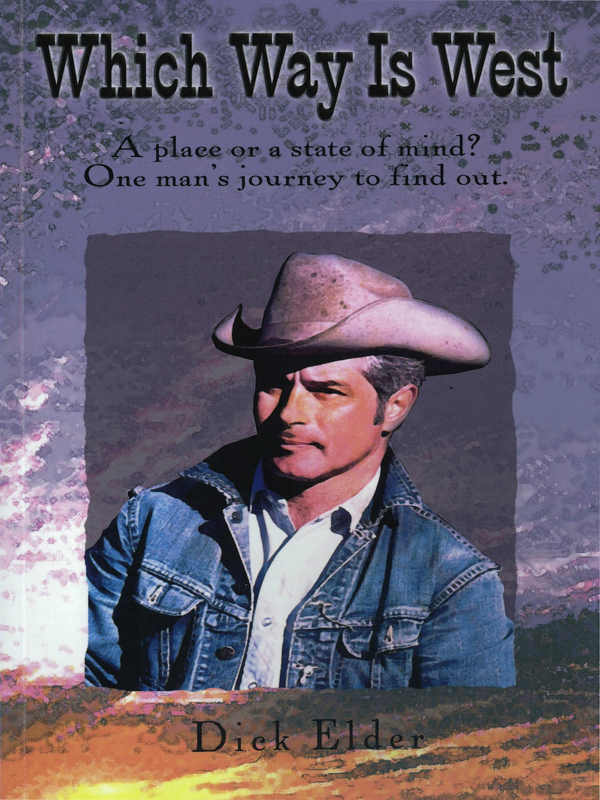

A place or a state of mind?

One man’s journey to find out

For my partners

Jim and Twila Dodson

George and Donna Horton

Without you, I wouldn’t have had the guts to do it.

And

George and Geneva Begley

Mel and Janette Schaefer

Without you, there would have been no pot of gold.

During the two and a half years spent writing this book, I bounced between elation and depression. The first draft contained over 400 pages which I thought were great.

I gave that draft to Gerry Shepherd, a good friend and author whose judgment in matters literary I respected. She read the book and told me exactly what I needed to know. I hated her for that! All that work for nothing or so I thought. But Gerry encouraged me to try again, shorten it up, stay focused, remove the trivia and keep the story moving. So I rewrote and rewrote a total of twelve times.

I gave subsequent drafts to other readers as well and asked for comments and I sure got them and they were not always complimentary. Rona Barrett was one of the first to see an early draft and while I’m sure she wasn’t that impressed with it, she insisted I stay with it and encouraged me to “rewrite ‘til I got it right.” Carol Ann and Tim Elwell had some fine ideas to share with me as did Mel and Jeanette Schaefer. Liz Hafer read draft number eight and filled the margins of the manuscript with copious notes and comments. These were extremely helpful in the subsequent rewrite.

By the time I had finished rewrite number ten, I thought it good enough to present the book to a professional editor. Dina Wolff and her parents had been guests at our ranch some years ago and a chance meeting in 2001 resulted in our collaboration. I sent Dina what I thought was the final version of the book for editing. Much to my chagrin, the manuscript came back with so many notes and comments, that after reading them, I chucked the damn thing in the waste basket. Then we had a heart to heart talk after which, I retrieved the red-penciled pile of trash and sat down to redo it once again. Thanks Dina, you done the right thing, by golly.

I have to acknowledge the patience my wife displayed during the past few years as I sat in my office hour after hour during the day and many a night punching computer keys.

My thanks go to my friends who encouraged me throughout this process and my former partners, Jim and Twila Dodson and George and Donnie Horton who shared those early years with me and helped me fill in some of the fuzzy details I couldn’t remember.

Finally and with no apologies, I thank the computer. No way in hell, would or could I have done this work on a typewriter.

My intention was to write a history of Colorado Trails Ranch from its inception to the time I sold it, but I soon realized that the more compelling narrative would be my personal story which would encompass more than just the building of the Ranch. What follows is an autobiography of a single decade, the decade in which I made the giant leap from security and a comfortable lifestyle to, well, what you'll read about on the following pages.

It doesn't particularly matter to me how this narrative is labeled. Call it an autobiography, a memoir, or whatever. I have elected to write in a style and tell the story as if I were chatting with you, face to face. But, in order to breathe life into the characters you will meet, I have deviated from true autobiographical style by recreating events through scenes with dialog. Though these moments took place some forty years ago, I do have, and please excuse me if I appear to be bragging, a remarkable memory with regard to how people talked in terms of manner, idiosyncrasies of speech, arcane phrases and their dialects. I can recall these conversations with virtual clarity and thus can, with a high degree of accuracy, recreate them for you.

Finally, while I shamelessly admit to flaws in my character, particularly my propensity to fool around (being unfaithful, to be precise), I do offer a rationalization which you may consider lame; nonetheless, I trust you will find that I do have some redeeming characteristics that may allow you to judge me in a more favorable light. By changing the names of some of the characters, especially those who might be embarrassed and displeased to see their names appear on these pages, I have exercised a partial redemption.

When the 1960s are recalled, most people think about the Viet Nam war, hippies, the counterculture revolution, long hair, free love, drugs, tie-dyed clothes, beads, and rock and roll. For me and my partners struggling to stay alive in Colorado, it was none of that.

Traveling through that decade was a marvelous adventure. I hope you too, will enjoy the trip.

The last echoes of Bob’s song had drifted to the far corners of the room. The candle-lit eyes now turned toward me as I mounted the stool next to the antique candelabra.

It was Saturday night and the chuck-wagon dinner and camp fire sing-a-long had ended after the staff and I had sung “Now is the hour when we must say goodbye.” Later, the guests had gathered in clusters and said their good-byes with handshakes, hugs and tears. I had invited the guests to attend a final get-together in the parlor and, despite the late hour, most of the adults and a few teenagers showed up to listen to Bob Bellmaine and me tell ranch stories and sing our songs.

I raised my guitar and ran my thumb lightly across the strings. “This song is about a twelve year old kid whose momma had died and shortly thereafter, his pa married a lady who beat the kid constantly. After one of the whippings, the lad decided to run away so early one morning, he quietly shoved some clothes and a couple blankets in a cotton sack and slipped out to the horse corral where he saddled a stout gelding. Tying a canteen to the saddle horn and strapping his bedroll behind, the boy headed west to find adventure.”

I played a G seventh chord, took a breath and began, “Well, he’s little Joe the Wrangler, but he’ll never wrangle more, his days with the ramuda they are o’er.”

The song frequently elicits a tearful response from the audience because little Joe is killed during a stampede. Bob claims the folks tear up because I’m a lousy singer, but my wife says it’s because I sing the old cowboy classic so well. I‘m not sure which one of them has it right.

I peered into the darkness and briefly left the moment, suddenly aware of the look of the room we now called “The Parlor.” Furnished with antiques, the décor was distinctly late 1800s. I instantly recalled a time when the room had a dirt floor and the walls were ugly gray cement block. During hunting season, we had cut up elk and deer here. Later, when we had a little money, we put in a concrete floor and used the room for a store and game room. Ten years had flown by since Jim, George and I began building the lodge. Ten years! So much had happened. So much had changed.

“Little Joe” was the last song of the Pow-Wow program. I thanked the folks for choosing Colorado Trails Ranch and was just about to say, have a safe trip home, when someone piped up with, “How’d you happen to get into dude ranching?”

I laughed. “Well, that’s a long story and it’s getting late.”

A chorus of voices from the darkened room shouted words of encouragement.

Bob laughed and I couldn’t help but chuckle. Every week our guests asked the same questions. How did you start? How did you happen to choose Durango? What did you do before you started the dude ranch and so on? Off handedly, I usually answered that it was just something I had always wanted to do, which was true. Facetiously, I might say I was a ham actor and half-ass musician and this job provided a captive audience. I guess that’s true too. Or I might say horses had been my hobby for many years and I just decided to turn my hobby into a business. That was definitely true. Most often, however, I’d just let it go with a quip, “It sure beats working!”

A lady sitting on the floor in front of me pleaded, “C’mon Dick, tell us about it.”

“Okay.” I sighed, sliding an old rocking chair next to the candelabra. Sitting down, I put the rocker and my story into motion.

Go confidently in the direction of your dreams.

Live the life you have imagined.

-Thoreau

Go west young man.

-Horace Greeley

I grew up a-dreamin’ of bein’ a cowboy.

The “Depression” was in full bloom in 1934 and I was seven years old when we moved to University Township, near Cleveland, Ohio. Warrensville Center Road, paved with bricks laid by the Works Project Administration, (created by President Roosevelt to put people to work), was a mile east of our rented home. East of Warrensville Center Road was the country. Folks who lived in Cleveland said we lived in the “boondocks,” or “out in the sticks.”

My father’s company manufactured artificial grass used to cover open graves and for decoration in store windows. Although times were hard, we had plenty to eat, lived in a nice house and, by contemporary standards, lived comfortably. We owned two cars, a 1933 LaSalle and a 1928 Huppmobile.

One of seven children, my dad grew up on a farm near the little central Ohio town of Shelby, so living out in the sticks was nothing new to him. He was forever taking our family out on weekend excursions looking for a farm to buy. Although we looked at a lot of farms, and they were dirt cheap during the 30s, he never did buy one. That was a disappointment for my two brothers and me because we were certain that once we had a farm, we would each have our own horse…naturally.

My mother, born in 1900, was three years younger than my father. She was a loving, caring and very gracious person who, as a stay at home mom, exercised a great deal of influence on her three sons giving us lessons, by example, on how one should conduct oneself in polite society.

My dad gave my mother, who knew how to play, a Fisher baby grand piano as a tenth wedding anniversary present and the day it arrived, I started banging on it. I guess it is from her that my musical talents spring. Within a few weeks, I began composing little tunes and several years later, when my folks thought I was old enough to take lessons, I wasn’t interested. Playing the silly simple stuff in the John Thompson Beginners Piano Book was boring, as by then, I was making up some quasi complex music. After a half a dozen lessons, I quit. That was one of the dumbest things I ever did because although I can play, I don’t play very well and to this day, I cannot read music with any degree of proficiency.

My brother Bob is five years older and Howard is about two years younger than me. On Saturday afternoons we would go to the movies at the Cedar Lee Theater in neighboring Cleveland Heights. It was a good bet that the double feature would include at least one and sometimes two “westerns.” We grew up with the great cowboy stars of the thirties: Hop-a-long Cassidy, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, John Wayne and Tim Holt. For just a dime, we saw two full length movies, a newsreel, a travelogue, and a fifteen minute segment of a serial that ended with the hero about to be killed. Large candy bars sold for a nickel, two for seven or three for ten cents. Twelve ounce bottles of soda pop cost five cents. We would spend an entire Saturday afternoon watching movies, eating candy and drinking soda pop for about twenty cents each.

After the movies, we’d come home, strap on our six shooters and chaps, put on our cowboy hats and vests with the little shiny conches and head for one of the many wooded areas near our house. Armed with boxes of caps for our pistols, we’d replay the movie, running through the woods on our imaginary horses, shooting Indians and generally having one hell of a good time. (It should be noted that shooting Indians in the 1930s was politically and ethically correct in as much as the Indians in the movies were always played by white guys.) At that point in my life, I had never seen a real Indian on or off the screen.

Willie Nelson must have had me in mind when he sang; I grew up a-dreamin’ of bein’ a cowboy, lovin’ the cowboy ways. Yep, that was me all right. My boyhood dreams were much like the movie serials we watched on Saturdays, a continuing saga in which I was the cowboy hero. The venue would always be the same. In fact, I can picture to this day what the cabin of my dreams looked like, what kind of pistols and rifle I used, the name of my flashy paint horse, the clothes I wore and so on. Night after night the story would continue like the weekly serials we watched on Saturdays.

I don’t know why, but horses have fascinated me since I was a very small child. Prior to 1934, we rented a house in a suburb known as Cleveland Heights where milk, ice, farm produce and bakery products were delivered by horse-drawn wagons. When I heard the sound of a horse’s hooves clip-clopping on the paved road, I’d run out to see the horse and visit with the salesman/driver. If the delivery wagon arrived around noon, the driver would feed his horse oats in a nose bag while he ate the lunch his wife had prepared for him. While they were eating, I’d chat with the driver, keenly aware of the grinding sound the horse made as he chewed the grain. The bakery wagon was my favorite because the driver gave me a cream-filled pastry horn or a soft sugar cookie that he took unwrapped from the white wooden drawers around which flies gathered. Although I looked forward to the baked treats, I enjoyed spending time with the horse even more. I think I understood, even at that early age, that these deliverymen had a special relationship with their horses.

One morning our milkman arrived in a shiny new Divco step van. “What happened to your horse?” I asked.

“No more horses,” the man sadly replied. “We gotta drive these new-fangled trucks now. You can whistle to one of these dad blame step vans ‘til you’re blue in the face, but it won’t do no good. They won’t come trotting up to ya like my ole horse did. By golly, I sure miss him.” So did I.

My brother Bob had a pair of baseball shoes fitted with metal cleats and I would put these on pretending to be a horse and go clomping around sounding very much like a shod horse on a paved street. Horses were a part of everyday life. When I saw a mounted policeman, (there were no female police) I would give his horse a pat. The affection those cops had for their mounts with their groomed coats and polished tack was apparent. There were hungry people everywhere but no police horse went hungry.

The many public parks near Cleveland were patrolled by mounted rangers (there were no female rangers) and each could tell me why his horse was so special. The affection and concern those men had for their horses was not lost on me, even as a young boy.

Seeing a tractor back then was something of a novelty and we would stop and watch, somewhat fascinated. But most farmers were working a hundred acres or less and still relied on horse drawn machinery. A farmer could buy or raise a work horse for very little money and since they had pasture and raised hay (hay sold for ten cents a bale) and grain, feeding horses cost practically nothing.

As kids living in University Township, our parents didn’t worry about our going someplace after dark or taking a streetcar or bus all the way to Cleveland to see a movie. About the only time we’d be indoors was to listen to the adventure serials on our Philco radio. We’d tune in Little Orphan Annie, Jack Armstrong, The All-American Boy, Tom Mix and others. The books we read as kids were mostly tales of high adventure with identifiable heroes like The Radio Boys (the radio being something of a novelty). There were no Radio Girls as the intricacies of the radio were, I assume, beyond the ken of females. Stories about Tom Swift, the Great War (WW I) and books involving airplanes, cars, ships, cowboys and life in the West, attracted our attention.

Children did not require, nor did they get, a detailed explanation from parents as to the ‘whys and wherefores’ of the many behavior edicts imposed upon them. Frequently the answer to a child’s question of why was, “Because I said so.” Spankings both at home and in school, were more the rule than the exception. Applied sensibly, this kind of discipline resulted in children who were basically well-behaved and respectful. We did as we were told and parents were not the least bit reluctant to tell us how we were to behave. This seemingly dictatorial method of raising children cut across all economic lines from poor and uneducated immigrants to the wealthy. I don’t think that any parent ever asked a child, “How do you feel about this?” Of course, Dr. Spock hadn’t written any books at that time either.

There were, however, inconsistencies that will seem at odds with what you have just read. I feel the need to tell you about them so that you may find it easier to accept my somewhat less than sterling behavior later in life. It has been suggested by some individuals that as a child, I suffered “sexual abuse.” I don’t believe it for a minute! I enjoyed the hell out of it. Besides, there was no such thing as sexual abuse back then, that is to say, no one ever put a name to it.

As with many families of modest wealth, we had full-time, live-in help whom we called maids. The customary weekly wage for five and a half days was six to eight dollars plus room and board. These maids were the teen-aged daughters of Eastern European immigrants. They knew little of the ways of the world and even less about sex. But, they were inquisitive and easily compromised, as was I. As a result of this unbridled curiosity, the girls and I (my brothers, as well) became involved in exploring one another. We never had intercourse but, we did a lot of touching and feeling and kissing. I knew all about the “French kiss” by age thirteen which doesn’t sound like such a big deal by contemporary standards, but trust me, back then it was huge. As a result, my view of the so-called sanctity of marriage and the sexual experience was diminished considerably. For me, it was just something to have fun with and I didn’t mind having fun. Was it sexual abuse? I don’t think so. Did all of that “fooling around” at that early age foster a pattern of sexual promiscuity? Perhaps. You can judge for yourself as this story unfolds. I relate these fundamentals of my upbringing and the environment of my childhood so that you will have an understanding of my social perspectives and how my childhood experiences colored many of my adult decisions. As they say nowadays, so you will know where I am coming from.

I was twelve years old in 1939 when we bought a home in Shaker Heights, an up-scale residential little town. Our large home on the corner of South Woodland and Montgomery was again within a few miles of the country side. My fun with maids abruptly ended when I was fourteen when my mother hired a married couple. Shaker Heights had excellent schools that provided a very good education. By my senior year, I could quote from memory all of Hamlet’s soliloquies plus the speeches of Mark Anthony and Richard III. I could read, write, solve mathematical problems using nothing more sophisticated than a pencil and paper, and recognize most of the great works of serious composers including Wagner, Brahms, Mozart, Beethoven, Billy Strayhorn, Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington. With my peers, I engaged in spirited conversation using English, a language betrayed by too many Americans these days. My friends and I frequented such venues as, The Crossroads Cafe, Louis’, The Ce-Fair Tavern and The Richmond Country Club. By the time we were seventeen, my friends Tom Fribley, Jack Bailey, Bluey Parino and a gaggle of other guys, had become serious users of beer and casual imbibers of hard liquor and I was no less of an imbiber than the rest.

Ah, ha! Now you are going to trip me up by asking, “What about doing what I was told?” I did say there were exceptions. For what it’s worth, here’s my excuse; World War II was going full blast when this unsanctioned behavior blossomed. We high school boys were convinced that we would be gobbled up by the draft, sent to Europe or the Pacific where, after fighting heroically, we would be killed. It really didn’t matter if we got drunk or didn’t do our best in school. In a year or two, we’d be DEAD! The logic of our less than perfect behavior should now be clear. It certainly was clear to us!

My best friend, Tom Fribley and I ran a little business in high school providing music for dances. We had an amplifier, a couple of twelve-inch speakers, a microphone and a turntable on which we played records. For those readers not familiar with the word “record,” substitute compact disk.

While we Shaker boys dated and tried to make out with Shaker girls, we never got very far, in fact, I never had intercourse with a girl nor did any of my high school friends. That was something we just didn’t do! We might get very close, but intercourse, never! (The phrase, having sex did not exist.) I’m not saying this phenomenon was universally true, but it was certainly true amongst the gentlemen and ladies of Shaker Heights High. Any girl, and there were very few, who went “all the way,” was unmercifully ridiculed and quickly found herself excluded from polite society.

Because my mother enrolled me in school when I was only four and a half years old, I graduated in January rather than June, 1945. I went straight into the Navy, having enlisted prior to graduation, in the Navy’s Combat Aircrew training program and subsequently got my Combat Aircrew wings as an aviation radioman/gunner. This, however, is not a “war story” so the only thing you need to know about that time of my life is that I wasn’t killed and I was no longer a virgin. You can’t beat that Navy training!

Honorably discharged from the Navy in September 1946, I immediately drove down to the Ohio State University in Columbus and enrolled in the College of Commerce and Administration just days before the fall trimester was to begin. You may find it enlightening to learn that my tuition for a full academic year was fifty-five dollars. No, that is not a typo, $55.00 is correct.

During my sophomore year, I met Marye Francis Jeffery, an eighteen year old from Cleveland Heights. Marye was very intelligent, very sweet, very innocent and very virgin when we started dating. I enjoyed being with Marye and after several months of steady dating, an irrevocable event took place. Pregnancy was, in our view, an irrevocable event. There were no options. No gentleman (and I was one) would walk away from a girl who was “in a family way” and no decent girl got an abortion. There were no exceptions. It was a rule set in concrete. You did the right thing. You got married and that was that. Many a postwar marriage took place under similar circumstances, so our situation was by no means unique.

My first encounter with Marye’s dad, Richard Werner Jeffery III, was in a café near the Ohio State Campus. He was at the University taking courses for his Doctorate and Marye seized the opportunity during dinner to tell him that she was going to get married. I was prepared for a big blowup with outrage becoming disbelief, then recriminations with a proper lecture apropos to the situation. To my surprise, he accepted the news without emotion.

The conversation went on to something else. Richard Werner Jeffery was not an emotional man nor did he seem that interested in what was going on around him. At least that is my take on it. On the other hand, Marye’s mother, Gretchen, was very aware of everything. She served in Europe as a nurse during World War I then earned a master’s degree in public health nursing and worked in that capacity for the city of Cleveland. She was a wonderful woman whom I admired greatly. She accepted the advent of our marriage with good grace.

Marye and I married in a little Kentucky town across the Ohio border. It was just us and a Justice of the Peace. It wasn’t very fancy and in retrospect I would have to admit that it was not a particularly joyous occasion. Had that set of circumstances taken place now, there is no doubt in my mind that Marye would have had an abortion and there would have been no marriage.

In January, 1948 our daughter, Nancy Gretchen, was born. When the new school quarter began, Marye attended classes in the morning while I fed, bathed and took care of Nancy. Just hand me a Curity diaper and a couple of large safety pins and I’ll show you how it’s done. When Marye returned from class in our 1934 Studebaker convertible, I’d drive the short distance to the campus and after my last class of the day, drive some twenty miles to my evening job at a Sohio gas station way out in the country. Since I took a full load of classes every summer, when most sensible students went on summer vacation, I was able to get my Bachelor of Science in Business Administration degree in just a little over three years. I couldn’t wait to get out of college. I wasn’t a particularly good student although I got A’s and B’s in the subjects in which I was interested and C’s and the occasional D in others.

Going to school from the time I got out of the Navy until I graduated in December, 1949 without the respite of summer vacations, being in a less than ideal marriage and having a child to worry about was hard and frequently frustrating. I was too damn young and irresponsible to be married and the consequent lack of freedom and the need to provide for my family while still attending college was just a bit more than my personality would allow me to deal with. I was either taking care of Nancy or going to school or working, and that regimen created a physiological overload. Maybe that’s too dramatic. Regardless, something was happening that didn’t bode well for the marriage. My first extra-marital encounter took place during my senior year.

“There is nothing so good for the insides of a man as the outsides of a horse.”

Armed with what was then considered a prestigious degree, I joined my father’s manufacturing company, receiving a generous weekly salary of one hundred dollars. (The minimum wage was thirty-five cents an hour). Dad had just retooled the plant and the new equipment had so many problems that production was seriously hampered. Being confronted with constant glitches and breakdowns was very beneficial for advancing my mechanical proficiency although it had little to do with advancing my college degree in marketing. I wasn’t particularly enamored with the job but I sure did learn a lot about using tools, fixing things, and understanding the underlying principles of how things work. Over time, I learned the production side of the business and when my uncle, the shop foreman, left to start his own business, I took charge of the factory.

My dad came to work every day about ten in the morning, looked at his mail, worked on his many charitable responsibilities, then left to have lunch and play cards at his downtown Club returning in time to leave for home by 4:30. He had the final say on major decisions, it was his company after all, but Bob and I ran the outfit. Ironically, my degree in marketing was of little value since brother Bob, who had not been to college, was the sales manager. Go figure.

In 1950, Marye and I were able to buy a new three bedroom colonial home for $19,000 by taking advantage of a 5% G. I. Loan available to veterans. Marye was pregnant when we moved in but went right to work planting a garden and getting everything ship shape. My folks helped us with money to buy new furniture and the other household necessities. Although we were within the city limits of University Heights, no longer a township, the area was sparsely inhabited. In fact, there was an operating farm directly behind our home, so we considered ourselves to be country folk. There were dozens of vacant lots on our street when we first moved there, but in a year or so, there were houses on most of the lots and the farm gave way to civilization.

On November 3, 1950 our son Mark was born and in July of 1951, my younger brother went off to the army and later was shipped to Korea as an artillery officer. I was fearful I would be called back, as I was still in the Navy Reserve as a combat air crewman and flying personal seemed to be in demand. Being married with two children probably saved me from participating in that unfortunate war. Excuse me, it was not a war; Korea was referred to as a “Police Action.” If you ask my brother who was in the middle of it, he’ll tell you it was, in fact, an honest to God war!

One evening in early 1953, I was sitting in my favorite chair waiting for Marye to announce that dinner was ready. She prepared a full course meal every single evening and had it ready by six and no part of it was made from anything instant or frozen. I should point out that this was not an unusual event. That scene was being played in millions of homes all across the country. I was watching the news on our Admiral TV with its nine-inch screen and drinking my favorite Old Forester bourbon, when Marye came in from the kitchen and said, “I’ve a grand idea for a vacation.” Grand is a word she would use.

I pulled an Old Gold cigarette from the pack and lit it with the Ronson table lighter (a wedding present). “Okay. I’m all ears.”

“A dude ranch.”

“A what?”

“A dude ranch called the Jack and Jill Ranch. It caters to singles, but I was told that some married couples go there as well. I think it would be a lovely change, something entirely different. You can forget about the factory, you can ride horses and-”

“A dude ranch? Why in the hell would I want to go to a dude ranch for God’s sake?”

~ ~ ~

At the Jack and Jill Ranch we met Peter McAllenan who was called Rocky. I have no idea why “Rocky” except that the management wanted all the wranglers to have cool nicknames. Rocky was the single most important influence for my becoming totally involved with horses. In my view, he defined the term Horseman. When Rocky sat on a horse, you couldn’t tell where the horse ended and the rider began because it was all one beautiful picture with horse and rider in perfect harmony. This oneness of horse and rider is something that every serious student of equitation strives to achieve but few ever attain. It was a thrill to watch that man ride and see the horses respond to his skill. After my first session with Rocky, I knew that this was the way it should be done. To emulate the man became my goal. Peter McAllenan was the most incredible horseman I had ever seen, and fifty years later after having been around hundreds, perhaps thousands of riders, I can still say he ranks in my top ten.

Our week-long vacation at the ranch opened my eyes to many new and wonderful experiences. It was a revelation! No, more than that, it was an epiphany. While horses and riding were the center-piece of their program, there were so many activities available that kept the guests busy and happy from breakfast until bedtime. I loved the trail rides, especially those guided by Rocky who allowed me to ride a neat little Mustang called, Popcorn. Hanging out with the “cowboys,” albeit very few were real cowboys, was a kick. They, like Little Joe the Wrangler in the song, didn’t know straight up about a cow but they wore the western outfits and rode horses.

The lively program at Jack and Jill suited that young, mostly single crowd. Ranch guests enjoyed singing around the campfire, late night entertainment called Pow-Wows, singing after lunch and dinner in the dining room that may seem square now, but at the time, was thoroughly enjoyed. The ranch held horse shows, awarded riding trophies, presented stage shows with staff as cast, provided many sports opportunities and offered a variety of entertainment. It was magic and I was hooked! When we returned the following year, I was absolutely convinced that I had found the perfect lifestyle if I wanted to lead a meaningful life. Many of my “original” ideas that I employed later on in life, originated at Jack and Jill Ranch.

I had been having stomach problems since my senior year at Ohio State University and the pain was getting worse. Finally, Marye insisted that I see Donavan Baumgartner, her family doctor. After a complete physical, he sat me down in his office and explained the strict diet he wanted me to follow which included a lot of rice but excluded coffee and liquor. I hated that! Then he leaned forward in his chair and in a solemn voice said, “In addition to changing your diet and cutting out the drinking, I want you to do something that I think will be the most important part of this regimen. Do you have any hobbies right now, something that you enjoy and do frequently?”

I shook my head. “No, not really. Well, I do like riding horses and I try to ride several times a week, but that’s not a hobby is it?”

“Well, it certainly could be. Doesn’t horseback riding require your complete attention? Seems to me that if you’re paying attention to your horse and thinking about what you’re doing, you won’t be thinking about things that tend to upset you and may be the root cause of your stomach problems.”

I couldn’t argue with that logic. Peter McAllenan had told me how important it was for a rider to always stay alert to what the horse was doing. The more I thought about it, the more I convinced myself that getting involved with horses could be my salvation.

Veterinarian Dan Stearns and I met one day at Andy Durek’s stables where I frequently rented horses. I asked him and Andy to be on the lookout for a horse that would suit me. Several weeks later, Dr. Stearns told me that Calumet Farms had a two year old mare at Thistle Downs race track that was having some knee problems and they wanted to “put her down.” Dr. Stearns thought this filly would make a nice riding horse and if I would agree never to race her, Calumet would sell her to me for a token price. I bought the Thoroughbred mare, Flying Mite, a granddaughter of the great Triple Crown Winner, Equipoise.

Flying Mite and the Jack and Jill Ranch changed my life completely and irrevocably.

The rider’s grave is always open.

I needed a place to keep my new horse and the problem was solved for me right next door. My neighbor introduced me to her brother, Sonny Breman, a slim young man who always wore Levi’s, cowboy boots with spurs and a cowboy hat. Curious, I asked him about his choice of garb. He told me that he trained and showed Quarter horses. That got my attention. He said he rented a nice six-stall barn on Johnny Cake Ridge Road in Willoughby Hills and would rent one to me.

I figured that Sonny was someone I needed to get close to and in a little while we became riding buddies. Sonny’s primary show ring event was cattle cutting, which basically is sorting cattle on horseback. I sold Flying Mite the following year and purchased a young Quarter mare named, Moab Cole a daughter of Babe Mac C, the first AQHA Champion. By this time I was totally committed to learning all I could about horses and riding. I intently watched others ride and took note of their methods then pestered them with questions that usually began with, why? I read every available horse-related book I could lay my hands on, including some written hundreds of years ago. I asked Sonny to help me train the mare for working cattle so that I could compete in cutting horse classes. We built a cutting pen, kept six to eight head of steers on the place to work the horses and we frequently hauled our horses together to horse shows. Sonny also introduced me to reining classes and other western show events. It wasn’t very long before Moab Cole and I were bringing home ribbons and trophies every week. When the doctor told me to get involved in a hobby, believe me, I got involved to the point where my regular job was interfering with my hobby. That presented some problems, because showing horses meant I would sometimes miss a few days at work, and that didn’t sit too well with my brother and dad.

In November, 1953 my daughter Lauren was born. She was a beautiful baby with a sweet personality. I knew that I should spend time with her, Nancy and Mark, but between riding horses, going to horse shows and working five days a week at the factory, the time I spent at home with my growing family was minimal. When I came home from riding I would either pour out a generous portion of Old Forester or drink half a bottle of my other favorite beverage, Harvey’s Hunting Port. I was, to be honest about it, a lousy father and a piss-poor husband. I was self-indulgent to the point that the only two things that were important were my relationships with and my intermittent extramarital romantic interludes brought about, I suppose, by some need, whether imagined or real, for intimate female companionship that I concluded was not available at home. Or, perhaps it was available at home, but I refused to recognize it. I reckon you could say that I had a bad case of the greener pastures syndrome.

The forty-five minute drive out to Willoughby Hills to ride my horse every evening was getting tedious. I was keen to get out of University Heights and buy some acreage out in the country where I could keep horses. In 1957 we purchased a property in scantily populated Chester Township in Geauga County. The four bedroom home, the four-stall barn with tack room and hay storage, the large riding arena and the five acres of lawns and fenced pasture, made the place just about perfect. With the horses there, I was able to ride every day, go to horse shows on the weekends and participate in all sorts of horse related activities. I and two of my children, Nancy and Mark, got involved with the Geauga County Sheriff’s Posse and within a year, I headed up the Geauga County kids riding program and wrote their horse owners hand book.

Living out in the country, potluck dinners with friendly neighbors, endless riding on sparsely traveled dirt roads, made our Sperry Road home perfect. Sonny and I were participating in horse shows almost every weekend and I was riding and training virtually every day after work. I met Kent Vasco, a young vet who was looking for a place to board his polo pony and I agreed to let him keep his horse in my barn. Kent and I hit it off from the start and we began to pal around. Kent loved horses and horse owners, especially rich horse owners with social standing. He had a tendency to be somewhat of a snob in that regard. We had interesting conversations about equine anatomy and physiology, diseases, lameness, and training problems. I would frequently go with him on farm calls to assist him as he treated his equine patients.

On July 1, 1958, a big bay gelding I was training fell over sideways landing on top of me. I should have checked with a doctor and had x-rays taken immediately, however I put it off, as I had a commitment to judge the big July Fourth Horse Show at the fairgrounds in Chesterland. I was on crutches and it was mighty painful, but I judged the show. The next day I checked into a hospital where they informed that I had a fractured hip and femur.

After a month in traction at St. Luke’s Hospital in Cleveland, I was released wearing a leather and steel appliance that was supposed to hold everything in place until the bones mended completely. I couldn’t go to work for over a month after leaving the hospital, but I did manage to go with Dr. Vasko on many of his calls.

During one of our trips to see a sick horse, Kent suggested that we start an equine hospital. He had located a large barn that he thought would be perfect. I’ll refrain from boring you with the details and simply say that we both put up some money and established the non-profit Northeast Ohio Equine Institute in a large barn not very far from my Sperry Road home.

We were accomplishing some noteworthy outcomes, even with difficult cases that other vets might have refused. Kent was the head of surgery and I was the administrator. In practice however, I did all kinds of things. I held cassettes for x rays (which was stupid even with the lead apron and gloves), and assisted in the O.R. as a scrub nurse, assistant surgeon, or anesthetist. I prepped, sutured, retracted and got both hands in and held organs while Kent did his thing. Over time, I learned many veterinary skills, and I loved it!

One afternoon, Kent took me along to see a horse that had been stung by a swarm of bees. Immediately upon our arrival, a young girl came running up sobbing that we had to do something without delay because her horse was down and wouldn’t get up and she was afraid he might die. Had she called the same day the horse was attacked, there may have been an opportunity to save him, however several days had passed and now it was too late. Knowing that the horse was terminal but understanding the need for the young owner to feel as though she had done everything she could to save her beloved friend, Kent made it appear as though he was doing something beneficial. In spite of the seemingly heroic regimen, the horse died. The young girl was devastated and Kent, being a soft hearted sucker, empathized. Sally’s vet bill came to several hundred dollars so she asked Kent if there was some thing she could do to work it off. Feeling sorry for the grieving girl, Kent invited her to dinner.

I guess my humor was not at its best after spending a month in the hospital and although I don’t recall the precise circumstances, my guess is that I was feeling sorry for myself and acting like a jerk and taking it out on Marye and the kids. In any case, we decided that it would be best for Marye and the children to get away from me. I recall that we talked about divorce but decided not to act on it, hence the hiatus to cool off. My wife and children went on an extended stay with my in-laws in California.

Kent, Sally and her girlfriend were to pick me up, but we decided to barbecue some steaks and spend the evening at home. After our meal, Kent went off with Sally, to console her I suppose, while I and the other girl, whom I judged to be in her early twenties, went downstairs to the recreation room. I built a fire, and then sat next to her on the sofa. She told me about her family immigrating to America after the U. S. government granted special visas to those Hungarian “freedom fighters” who had escaped during the revolt against the Soviet Union. The warmth of the fire, the flush of the bourbon I was sipping and the charming personality of this girl, inspired romance, not that I ever needed much inspiration in that regard. Before long, we were kissing and feeling but Sonja was not about to go further.

No doubt about it, Sonja was a peach with light blond hair, lovely blue eyes and a very attractive figure. During the next few months, I saw a lot of Sonja and I think I fell in love with her but I was still married with three kids and that was a fact of life that I could not ignore in spite of my penchant for self-indulgence. In the end, I knew I had to bring my family back home. In spite of tearful remonstrations from Sonja, I went to California where Marye and I came to some sort of understanding. There still remained the underlying problem exacerbated by the lack of a loving relationship. Given the circumstances of our marriage, I doubt that there ever existed the bond necessary for our marriage to prosper. There was no appropriate resolution other than a truce that allowed the marriage to continue for the benefit of our children. That course of action, really non-action, turned out to be no resolution at all.

After Marye and the children returned, I continued to see Sonja. I just could not give her up. Was that a good idea? Probably not.

Late night may not be the best time to make life-changing decisions.

On April 26, 1960 our son, Richard Bradley was born. I think he was conceived while I was in California collecting the family for the return to Ohio proving yet again my lack of maturity in matters sexual. Our other children had arrived at intervals of three years which suggests that there was some thought given to family planning. Now, this baby showed up six years after Laurie was born.

A month or so after Brad arrived, I was working a horse in the arena when my daughter Nancy ran out of the house yelling, “Doctor Vasko is on the phone.”

“Okay. Tell him I’ll call him as soon as I get this horse cooled down.”

I was taking off the saddle when Nancy came back out and said, “Doctor Vasko called back and said he was coming over to get you. It’s an emergency. Some horse has a broken leg.”

Kent arrived and we hitched up my Circle M trailer in case we needed to haul the horse back to the hospital.

At our destination, we found the animal, a large gray Thoroughbred ex-jumper. He was standing quietly in a pasture behind the stables. It didn’t take long to figure out the problem; a fracture of the left hind leg between the hip and the stifle joint. This was exactly the sort of injury that usually ended with a shot to the head or a lethal injection, but it was the type of injury our hospital was dedicated to repairing.

We informed the owner that this was going to be a pretty touchy situation, that we could not guarantee a good outcome and further, that the horse may still have to be “put down.” (A euphemism for killed) In spite of the risks, the owner wanted us to do all that we could for the animal.

The problem was getting the horse into the trailer. It didn’t have a ramp which meant that the horse had to step up about six inches, put his two front feet inside, and then walk up, which he was unable to do.

Leaving Kent with the horse, I drove back to the hospital, dropped off the horse trailer and hooked onto our mobile operating table. It was dusk when I arrived back at the farm and positioned the table close to the horse. Sedating the old gray, we placed his three good legs on the foot board, put the body bands around him and finally the thick cotton leg ropes. The table had a hydraulic tilt mechanism so that as we began to lay the table down from its vertical position, we simultaneously tightened the body bands and leg ropes to keep our patient in position on the table.

When the horse was secure with a tarp covering everything except his head, we took off down the highway. Picture this: A twelve hundred pound horse lying on his side going down the road on a table with wheels. Although he was sedated, every now and then he would raise his head and neck and have a look around. People in passing cars gawked, unbelievingly.

It was a long night in the operating room. When the fracture had been reduced, and a walking cast applied, I washed the plaster off my hands and called two friends, George Horton and Jim Dodson. I told them what was going on and asked if they could come over and give us a hand. A short time later they arrived, and around eleven we had the old gray in a sling in the recovery stall. Kent went home, but George, Jim and I drove over to George’s house where his wife, Donnie, having been awakened by our arrival, got out of bed and made coffee and steel cut oatmeal.

We sat in the living room enjoying the late night snack while watching Johnny Carson chatting with Jonathan Winters on the TV. Suddenly, I blurted out, “I wish to hell I had gone to vet school instead of business school because I really do enjoy that cutting and slashing stuff.” The guys just looked at me but made no comment. I continued, “Doing surgery on horses is exciting! I love it! Vasko is letting me get more involved. Tonight, on that fracture, I was clamping and tying off bleeders and having a hell of a good time.”

George looked at me and nodded, but Jim spoke up. “You ought t’do it full time then if you enjoy it so much.”

“Hell, I’d love to if we had enough business but Kent and I still have to subsidize it.” I laid my spoon down and looked around the room. “I’ll tell you one thing and I ain’t shitin’ you, sorry Donnie. One of these days I’m gonna get the hell out of that damn factory and get into something that has to do with horses.”

George swallowed a mouthful of oatmeal. “Like what?”

“Oh, I don’t know—maybe a dude ranch. Something like that Jack and Jill Ranch Marye and I went to. I’ll tell ya, that was fun and the people working there were havin’ as much fun as the guests.”

Jim’s face lit up. “Now, there you have something. A dude ranch! By gosh that’d be all right ya know it. The three of us could quit our jobs, buy us some land out west some place and go to ranching. Besides the dudes, we could have cattle and horses and that sure would beat the heck out of sellin’ X-ray machines.” Jim was sitting on the edge of his chair waving his arms around, his blue eyes shining. Getting to his feet and walking toward the TV, he said, “Can’t you just see it George, it’s the answer to the whole thing.” Jim reached out and switched off the TV.

“Hey, what the hell you doing? Turn that back on. I’m watching that.” George rose from his chair but Jim laid a hand on his shoulder and pressed him back.

“Listen,” Jim said holding George with one hand and turning toward me, “this is more important than Johnny Carson.”