Rory Hyde

Hyde is currently Curator of Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism, V&A Museum. A graduate from RMIT School of Architecture and Design, Hyde previously worked for international and local architecture practices. In 2012, Hyde authored his first book Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture. Hyde is an adjunct senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne.

Ben Waters

Waters is director and cofounder of Studio Osk, Melbourne. He graduated with a Master of Architecture from RMIT University and studied at Parsons School of Design, New York. Waters is active in design research and currently leads architecture design studios at the University of Melbourne and Monash University.

Mariana Pestana and Suzanne O’Connell

In 2010, Pestana and O’Connell cofounded The Decorators – a design practice incorporating the disciplines of psychology, landscape architecture and interior architecture. Their design process encourages community engagement through establishing connections with local authorities and public institutions. In 2015, The Decorators launched their first book, Ridley’s: Recipes for Food and Architecture.

Simona Falvo

Falvo is a graduate architect from the Melbourne School of Design with a strong interest in cinema, among other things. She is interested in the intersection between architecture, philosophy and meaning and enjoys, whenever possible, the opportunity to travel and experience the world.

Janet McGaw

McGaw is an architect and academic from the University of Melbourne with a PhD by Creative Works. Her research, teaching and creative practice investigate ways to make urban space more equitable, leading her to a collaborative installation in the international exhibition Feminist Practice and work on Indigenous placemaking. McGaw also teaches and publishes in the field of Design Research methods.

John Wood

Wood is a design theorist and Emeritus Professor of Design at Goldsmiths College, London. He is cofounder of the international network, Writing-PAD, and coeditor of its publication, Journal of Writing in Creative Practice. Wood established metadesigners.org in 2005 and, via his company Creative Publics Ltd, is currently applying a much-developed version of his theoretical framework within a commercial context.

Eleni Han

Han graduated as an architectural engineer from the University of Thessaly and holds a Diploma in Architectural Design from the University of Pennsylvania. She is currently working on international design projects in addition to writing research papers regarding the future of architecture and its socio-economic impact.

Markus Jung, Maud Cassaignau, Jon Shinkfield and Matthew Xue

Jung and Cassaignau are researchers from Monash University in the department of Art, Design and Architecture. After working for a number of international architecture practices they cofounded XPACE: architecture + urban design. Their design practice explores the intersection of culture, technology and aesthetics within space production. Jung and Cassaignau partnered with Shinkfield and Xue for the Sponge City project.

Blake Jackson

Jackson is an architect, associate and Sustainability Practice Leader at Tsoi/Kobus & Associates, Cambridge, and an adjunct faculty member at Boston Architectural College. He is also cochair of the American Institute of Architects’ Committee on the Environment (COTE) and a board member for A Better City – a not-for-profit organisation that advocates sustainable development.

Luke Pearson

Pearson is a current PhD candidate at the Royal College of Art, London, and tutor at the Bartlett School of Design. His research focuses on the application of art and architecture into drawing and fabrication. Pearson has previously edited the periodical ELEVEN and in 2005 was awarded the RIBA Bronze Medal.

Alex Holland and Stanislav Roudavski

Holland is a graduate architect from the Melbourne School of Design with a research interest in games as tools for participatory design. Roudavski is a researcher and senior lecturer from the University of Melbourne whose work explores how participation, processes and design outcomes are likely to change under the influence of technology. Together, they work on projects that seek to support design as a form of activism.

Lateral Office

Founded in 2003 by Mason White and Lola Sheppard, Lateral Office is an experimental design practice based in Toronto, Canada, that operates at the intersection of architecture, landscape and urbanism. The firm’s recent work has focused on design relationships between the public realm, infrastructure and the environment that engage with social, ecological and political contexts.

Tristan Da Roza

Da Roza graduated from the Melbourne School of Design in 2016 with a Master of Architecture, and was a finalist in the AIA Graduate Award for his thesis project Start-Up Sovereignty. He is focused on working across the disciplines of architecture, urbanism and property development, to address the social and financial forces that contribute to equity in the built environment.

Giuseppe Resta

Resta is a current PhD candidate at Roma Tre University and an assistant for the design studio course at Politecnico di Bari, Italy. Regularly participating in international conferences, Resta is the architecture editor of Artwort. In 2016 he curated Evoked – Architectural Diptychs at FAB Gallery in Tirana. His research interests surround contemporary mixed-use buildings and their iconic value.

Joseph DeBenny

DeBenny studied architecture at the University of Arizona CAPLA, graduating in 2015. With a particular interest in writing, his research focuses on critical theory, performance-oriented architecture and continental philosophy. An avid blogger, DeBenny believes students can offer a unique perspective on the tenets of architecture, unrestricted by the dogmas of traditional theories of practice.

Jeremy McLeod

McLeod is an architect and founding director of Breathe Architecture, Melbourne. He is cofounder of The Nightingale Model – an architect-led multi-residential development model that offers a triple-bottom-line alternative in the housing market. McLeod and his team completed the award-winning Nightingale prototype, The Commons, in 2013 and are currently administering the construction of Nightingale 1.0.

Fabian Prideaux

Prideaux is a humanitarian shelter architect and a program advisor at Humanitarian Benchmark Consulting, a social enterprise based in Jogjakarta. A graduate of the Melbourne School of Design, his choice of vocation was inspired by his participation in the School’s 2010 Bower Studio, which has students working with remote indigenous groups to provide essential buildings and infrastructure. Prideaux has since worked on major humanitarian and development projects in Nepal, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Christina Varvia

Varvia is an architect, researcher and the project coordinator at Forensic Architecture. A graduate of the AA School of Architecture and the Unknown Fields Division, Varvia worked for architecture and construction practices before joining the Forensic Architecture team in 2014. She is currently developing methodologies and undertakes analysis through architecture and time-based media. Her work with Forensic Architecture has been exhibited in the UK, France, Belgium, Italy, Canada and China.

Lucas Koleits

Koleits is a graduate architect from the Melbourne School of Design and holds a Master of Antarctic Science from the University of Tasmania. He is interested in the social, economic and technological ecologies that shape and influence contemporary architecture, and seeks opportunities to creatively manipulate these conditions.

Editorial

Rory Hyde:

Future Practice Now

Ben Waters - Studio Osk:

Stadtumbau

Mariana Pestana + Suzanne O’Connell:

The Decorators

Simona Falvo:

Toward a Cinematic Architecture

Janet McGaw:

Design Research

John Wood:

Metadesign

Eleni Han:

Hybridisation - Synergy of Architecture + Biology

Maud Cassaignau, Markus Jung, Jon Shinkfield + Matthew Xue:

Sponge City*

Blake Jackson:

Transdisciplinarianism - Innovation through Sustainable Practice

Luke Pearson:

Architectures of Ironic Computation*

Alex Holland + Stanislav Roudavski:

PocketPedal

Lateral Office:

Making Camp

Tristan Da Roza:

The Age of Start-Up Sovereignty

Giuseppe Resta:

Scptipmflippes

Joseph DeBenny:

Architecture Needs an Enema

Jeremy McLeod - Breathe Architecture:

Nightingale

Fabian Prideaux:

Humanitarian Shelter

Christina Varvia - Forensic Architecture:

Architecture Screams Before It Dies

Lucas Koleits:

An Embassy for the Fourth World

* denotes articles that have been formally peer-reviewed

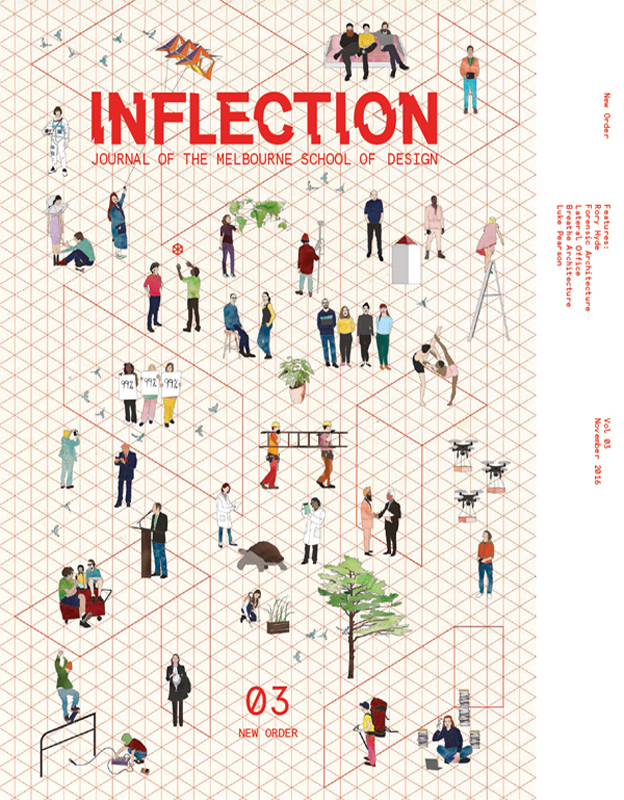

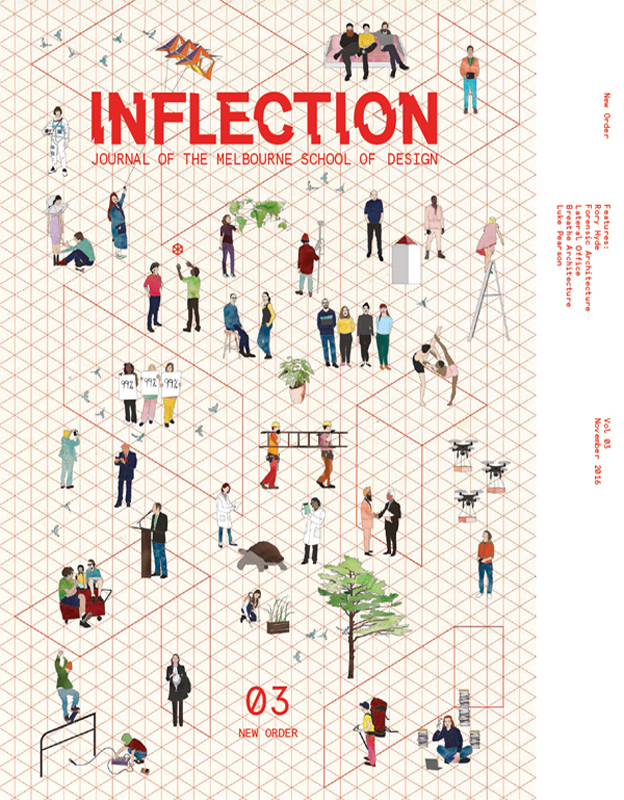

EDITORIAL BY COURTNEY FOOTE, JOHN GATIP + JIL RALEIGH

In the context of recent global political and economic disruption, architecture seems no longer equipped to address the demands of contemporary society as an isolated discipline. The old order of segregated industries and disciplinary elitism is collapsing, threatening to destabilise the foundations of architecture. A new, indeterminate paradigm is emerging, allowing architects to reconsider the nature of their practice – one currently at risk of cultural and political redundancy. One solution offered in this crisis of relevance is the notion of transdisciplinarity. Characterised by the hybridisation of distinct disciplines, this concept has risen to become a celebrated mode within contemporary architectural practice. Transdisciplinarity is the New Order.

This moment of adjacencies resembles art historian Rosalind Krauss’ critique of synthesised art practice. Her 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” sought to identify the intrinsic qualities of sculpture, architecture and land art at the point at which the three disciplines were being hybridised. 1 In defining the limits of each discipline, the concept of an ‘expanded field’ provided a space to properly establish what each discipline was, and what it might become if strategically combined with adjacent disciplines.

Architecture theorist Anthony Vidler translated Krauss’ thinking to an architectural context in 2004. His adaptation, “Architecture’s expanded field,” similarly assessed the limits of disciplinary borders against categories as far-reaching as biology, politics and technology.2 For Vidler, the expanded field was concerned with what occurs at the edge of conventional architecture as a means of innovation.

Both these historic perspectives describe an impasse between disciplinary essentialism and shifting practices. Yet the spatial character of expanded field terminology itself also hinted at movement across or beyond, encouraging the transgression of established borders.

Subsequent developments in architectural discourse revealed the solidifying identity of this movement. In 2009, RMIT’s Mark Burry and Terry Cutler curated Designing Solutions to Wicked Problems: A Manifesto for Transdisciplinary Research and Design, a symposium premised upon the idea that while transdisciplinary research is the natural habitat of the polymath, any broadening of professional remit is reliant on deeply specialised knowledge.3 Far from diluting the integrity of the core discipline, transdisciplinarity has the capacity to enrich conventional modes of research or practice.

This porous disciplinary boundary has been embraced within a contemporary conception of architecture and is now recognised by the wider architectural community. This is most recently demonstrated by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena’s curatorial ambition for the 2016 Architecture Biennale, Reporting from the Front. Aravena sought to expand the scope of architecture by engaging social, political and economic fields.4 This intention is symptomatic of the trend towards architecture as a transdiscipline.

Transdisciplinary practice extends conventional notions of architecture, displacing the production of built form as the prevailing mode of practice. Projects once considered to be on the ‘fringe’ of architectural practice are now routine; the expanded field is now embraced and authenticated by the architectural establishment and public expectation. Through a series of built projects, conversations and provocations, this issue of Inflection offers a survey of this expanded mode of architectural practice and presents a network of transdisciplinary interactions through which architecture can now contribute.

New Order begins with a reflection by V&A curator Rory Hyde on the developments in the field since the publication of Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture.5 The journal then turns to an inspection of the interaction between art, curatorial practice and architecture through projects by local practice Studio Osk and London-based The Decorators, and an essay on the relationship between cinema and architecture by Simona Falvo. Design theorist John Wood discusses the potential for creative synergies through collaborative relationships, then Janet McGaw discusses transdisciplinarity in architectural design research. This leads the narrative toward bio-design research and Eleni Han’s consideration of hybrid architectures, in which nature and the built environment are synthesised. A transdisciplinary team of experts, headed by Maud Cassaignau and Markus Jung, describes the potential of architecture when coupled with hydrology. Boston architect Blake Jackson then provides an account of the practical experience of transdisciplinarity in the context of sustainable practice.

New Order shifts briefly from the physical to the virtual through Luke Pearson’s proposition that the practice of videogame creation operates as a legitimate architectural design tool. Continuing this alignment with computational expertise, Alex Holland and Stanislav Roudavski present a smartphone game designed to enhance conventional participatory design processes. A return to the material world is signalled by Toronto-based Lateral Office’s account of the temporary inhabitation of wild landscapes through the lens of sociology and geography. This enquiry into modes of ‘occupation’ is broadened to the global arena, as Tristan Da Roza explores the geopolitical consequences of transnationalism. Inflection then takes an anti-geographic and anti-technological detour via Giuseppe Resta’s device that reframes the maritime landscape.

This investigation of transdisciplinarity and architectural practice encounters a warning from Joseph DeBenny, who postulates that the mere accumulation of disciplines will not result in a transdisciplinary utopia. He offers a method for mitigating the risks of mediocrity inherent in disciplinary interactions. But DeBenny’s caution is answered by the last portion of the journal, which offers irrefutable evidence that transdisciplinary interactions are effecting consequential change on a local and global scale. In engaging with the fields of finance, humanitarian aid, politics and international law, the works of architects Jeremy McLeod (Breathe Architecture), Fabian Prideaux, and Christina Varvia (Forensic Architecture) demonstrate the potential of this new mode of practice.

New Order ends with Lucas Koleits’ speculative embassy for micronations; a timely probing of the relationship between architecture and ideology as the global community finds itself in a moment of political, environmental and philosophical uncertainty.

Together these contributors demonstrate a critical response to the discipline of architecture in the 21st century. No longer bound by form-focused rules, architects are now able to find a new way of engaging with the natural and built environment through transdisciplinary practice. Amidst political, cultural, social, economic and environmental uncertainty, architecture must embrace its permeability, as architects engage with and synergise knowledge from multiple disciplines. Through this critical investigation of this contemporary mode of practice, Inflection Volume 3 explores the achievements, limitations and future implications of this transdisciplinary age, weaving together a fragment of the tapestry that is expanded architectural practice. In tracing the trajectory of this New Order, this issue uncovers the matter that binds architecture together in this fragmented, yet hyperconnected epoch.

01 Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October Vol. 8 (1979): 31-44.

02 Anthony Vidler, “Architecture’s Expanded Field: finding inspiration in jellyfish and geopolitics, architects today are working within radically new frames of reference,” Artforum International Vol. 42, No. 8 (2004): 142-148.

03 Mark Burry & Terry Cutler, Designing Solutions to Wicked Problems: A Manifesto for Transdisciplinary Research and Design, Melbourne, 2009 (Melbourne: RMIT Design Research Institute), http://www.designresearch.rmit.edu.au.

04 Alejandro Aravena, “Reporting from the Front, Venice, 2016,” Biennale Architettura 2016, accessed August 10, 2016, http://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/exhibition/aravena/.

05 Rory Hyde, Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture (Routledge: New York, 2012).

WITH COURTNEY FOOTE, JOHN GATIP + JIL RALEIGH

muf architecture/art, “More than one (fragile) thing at a time,” installation, All of This Belongs to You exhibition, V&A, London, 2014. Photograph by Max Creasy.

As Curator of Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism at the V&A Museum, Rory Hyde’s vision for the future of the discipline looks beyond the convention of building design. A champion for fringe practice, his curatorial oeuvre celebrates design that develops new forms of spatial engagement with our increasingly dynamic cities.

The origin of these ideas were present in his work as an ‘unsolicited architect’ where, somewhat covertly, he distributed paste-ups around the streets of Rotterdam with alternative design schemes for the city. Later refining these strategies in 2012, cocurating the exhibition New Order with Katja Novitskova for Mediamatic in Amsterdam, Hyde gathered an array of creative disciplines including artists, graphic designers and architects to consider energy and creative production in a post-carbon world.

By fostering these disciplinary interactions, Hyde continues the premise of his book – Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture – and opens the discourse surrounding spatial production to practitioners in and around the discipline of architecture. Working across the fields of exhibition design, curatorial practice, events, writing and architecture, Hyde himself embodies the transdisciplinary methodology. His most recent exhibition All of This Belongs to You at the V&A considers the role of the museum in representing contemporary experience.

During his visit to the Melbourne School of Design, Inflection talked with Hyde about how the ‘edge’ could be introduced within the context of the design museum:

I: To start, could you comment on when you first identified shifts in the role of the architect?

RH: I was studying at RMIT in the Spatial Information Architecture Laboratory (SIAL), looking at how new forms of technology were affecting design practice. That was the subject of my PhD, which was a fairly academic affair, but the conclusion took a bit of a leap to speculate on where these tendencies and technologies might take us. That thinking eventually became the book Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture, which was a more journalistic approach to the same topic, told through a series of interviews with the people and practices actually working in these new ways.

I: In our work on this theme, we’ve found it can be tricky to describe exactly what a transdisciplinary approach or ‘expanded practice’ is. How did you determine who was at the edge?

RH: I’m interested in people and practices who somehow subvert or challenge their assumed mode of working, or who pluck strategies from other disciplines. Of course it’s a fluid edge. At one end of the spectrum there’s the more conventional architects – practices like ARM [Ashton Raggatt McDougall], Studio Gang or OMA/AMO. And at the other end you have practices that have very little to do with architecture, such as BERG, who are technologists and product designers, or Natalie Jeremijenko, who works as an artist-designer-ecologist, or Marcus Westbury, who has a background running arts festivals. I would argue that all of these people can point us toward a different way of doing architecture, whether they know it or not.

Hyde pictured with Bin Dome.

Rory Hyde, “Bin Dome,” pavilion, Melbourne Now exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013. Photograph by Amy Silver.

So when ARM write secret messages in braille on the National Museum of Australia, such as “sorry” or “forgive us our genocide,” they point to a critical way of working where the architect is not a mere subservient service provider, but has an independent critical voice that may not be shared by the client. In this case, they said something through the architecture of a national institution that the government of the time wasn’t prepared to say. In a different way, BERG’s research into the invisible worlds of magnetic swipe cards and RFID readers – like your Myki card – can point to a new understanding of digital-real space.

What links all these people together is a sense that they have developed new tools that we can learn from, and even add them to our own design toolkits.

I: Your own practice, taking in curating, research and even designing pavilions, could also be described as transdisciplinary. How do see your projects such as the Bucky Bar or Bin Dome as expanding the field of architecture?

RH: On the one hand they’re just a chance to do something fast, a chance to do something really performative, to bring that immediacy back into architecture. But really it’s a way to confirm this belief in the power of architecture as a catalyst for social effects. Both these projects were driven by creating playful scenarios for people, a kind of minimum architecture of event.

But I don’t see a strict line of distinction between these more flimsy and temporary works and something more permanent and ‘real’ like this building we’re sitting in. It’s just that the stakes are higher for something made in concrete, you need to ensure that the social effects your building is imparting – over months, years, decades, centuries even – are positive ones, rather than negative ones.

And that perhaps links back to the idea of misguided modernity, which I think is in the background of all my work. The idea of questioning or challenging the authority of the architect, the over-confident form-maker, which gets replaced by something that’s a bit more provisional, a bit more about asking questions, rather than delivering a manifesto. To work with the public rather than dictating to them. I think those pavilions were a bit about that.

I: Many of your projects and provocations engage with architecture as a public good, a kind of democratisation perhaps.

RH: As architects we have this very generous civic training, we are taught to serve the public good. I don’t think anybody comes out of architecture school feeling cynical, like they just to want to – I don’t know – build the tallest tower for the most miserable developer. No, you want to build a library, you want to build a town hall, you want build a civic space, you want to design a public square or a train station.

But then something happens when you take your first job and you realise that serving the public good is about 1% of what you do. Instead the things driving your designs are not the generosity for the public space, but the carpark grid and the square metre cost. And that’s fine, that’s what architecture is a lot of the time, but perhaps it’s not what I’m interested in anymore. So I guess the big project has been to try to reframe the architect as a ‘custodian of the built environment.’ Or, to put it in less grandiose terms, it’s simply about seeing what happens if you zoom out one layer. To position the work in a larger context, and to take seriously our obligation to the big public, as well as to the client.

I: You’ve described the conventional practice of architecture as being like a ‘fortress’ – closed on itself, protecting the status quo, not letting anything new inside.

RH: That’s right, and the kind of practices I was interested in were always somehow illegitimate, marginalised, sideshows. That somehow in order to be a ‘real’ architect you had to be building private or commercial work in an urban centre.

But I think what happened with the economic crisis, is that these marginal practices, the people who weren’t getting published or getting loads of work, but who were working in a particular way that was local and responsive, were suddenly looked at as the new leaders. They’d developed tactics that were resilient and engaged, which then really started to resonate, and shift the centre. So I don’t find these binaries so useful anymore, it feels much more unstable now. Alejandro Aravena wins the Pritzker Prize, Assemble win the Turner Prize, and these simplistic distinctions of conventional or traditional practice versus the fringe or edge no longer make much sense.

I: You’ve now moved into the institutional sphere of a big museum. How are you able to maintain this position in this context?

RH: Yeah that’s a really good question, because I’m in the centre now! The V&A is the status quo in many ways. It’s a giant cultural monolith, one hundred and fifty years old, with seven hundred people working there. It has so much baggage historically, but also public expectation of what ought to be in the future. Through our exhibition All of This Belongs to You, we’re asking questions like, “How can you break these assumptions? How can you turn it inside out? How can you make it a radical place?” Our answer is to point backwards and say, “There is a radical history in this place too.”

The V&A was founded on the very idealistic, utopian and perhaps patronising idea that design has the power to improve society, that exposure to beautiful things can make you a better person. And I think we certainly feel this still somewhat holds true today, that objects and ideas can have a profound effect, and can be vehicles to tackle the big questions of society.

I: What happens next? Can the centre push back out to shape the edges?

RH: My problem is when you become interested in the edges, there’s no end, it just keeps going. It’s a limitless field, only bounded by your curiosity. So I feel like I’m leaving architecture behind more and more, and that’s probably okay for now. The next project I’m working on at the V&A goes way beyond architecture into science, design, technology, medicine and even space. Which comes back to your theme of transdisciplinarity.

I: What happens when this expansion goes so far it leaves architecture behind?

RH: The questions I get a lot are: “Are you anti-architecture? Are you anti-buildings?” And you have to remind them that borrowing tactics from adjacent disciplines, or collaborating with improbable professionals is all about making better buildings. It’s about questioning the authority of the architect’s knowledge, and supporting it with other forms of knowing and making in order to be more relevant. But sometimes I do worry we might also be trading away our core strength. That somehow this curiosity can take you to places that have very little to do with architecture. Which of course comes back to the question “What is architecture, anyway?” On the surface it’s simple: it’s the design of buildings and places, right? But to me that sounds too specific. It doesn’t accommodate situations where the best thing might be to demolish a building, or do nothing at all. It’s the Cedric Price world of strategies: “You don’t need an architect, you need a divorce!”

Our job can’t just be building, because then you only have the same answer to every problem. Like a surgeon who always elects to amputate, regardless of the patient. That’s why I like the phrase ‘custodian of the built environment’ – because somehow it can incorporate a more diverse form of practice. If that’s how you imagine what you do, then perhaps it leads you to explore ‘other ways of doing architecture,’ as Jeremy Till puts it.