JOHN G. O’DWYER, author of Tipperary & Waterford – A Walking Guide, is a travel consultant and is a regular contributor to The Irish Times. A keen hillwalker and rock climber, he founded the Mid-Tipp Hillwalkers Club and has almost thirty years’ experience of leading hillwalking and mountain-climbing groups in Ireland, the UK, Europe and Africa.

www.pilgrimpath.ie

Hillwalking and mountaineering are risk sports. The author and the publisher accept no responsibility for any injury, loss or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook.

Advice to Readers

Every effort is made by our authors to ensure the accuracy of our guidebooks. However, changes can occur after a book has been printed. If you notice discrepancies between this guidebook and the facts on the ground, please let us know, either by email to enquiries@collinspress.ie or by post to The Collins Press, West Link Park, Doughcloyne, Wilton, Cork, T12 N5EF, Ireland.

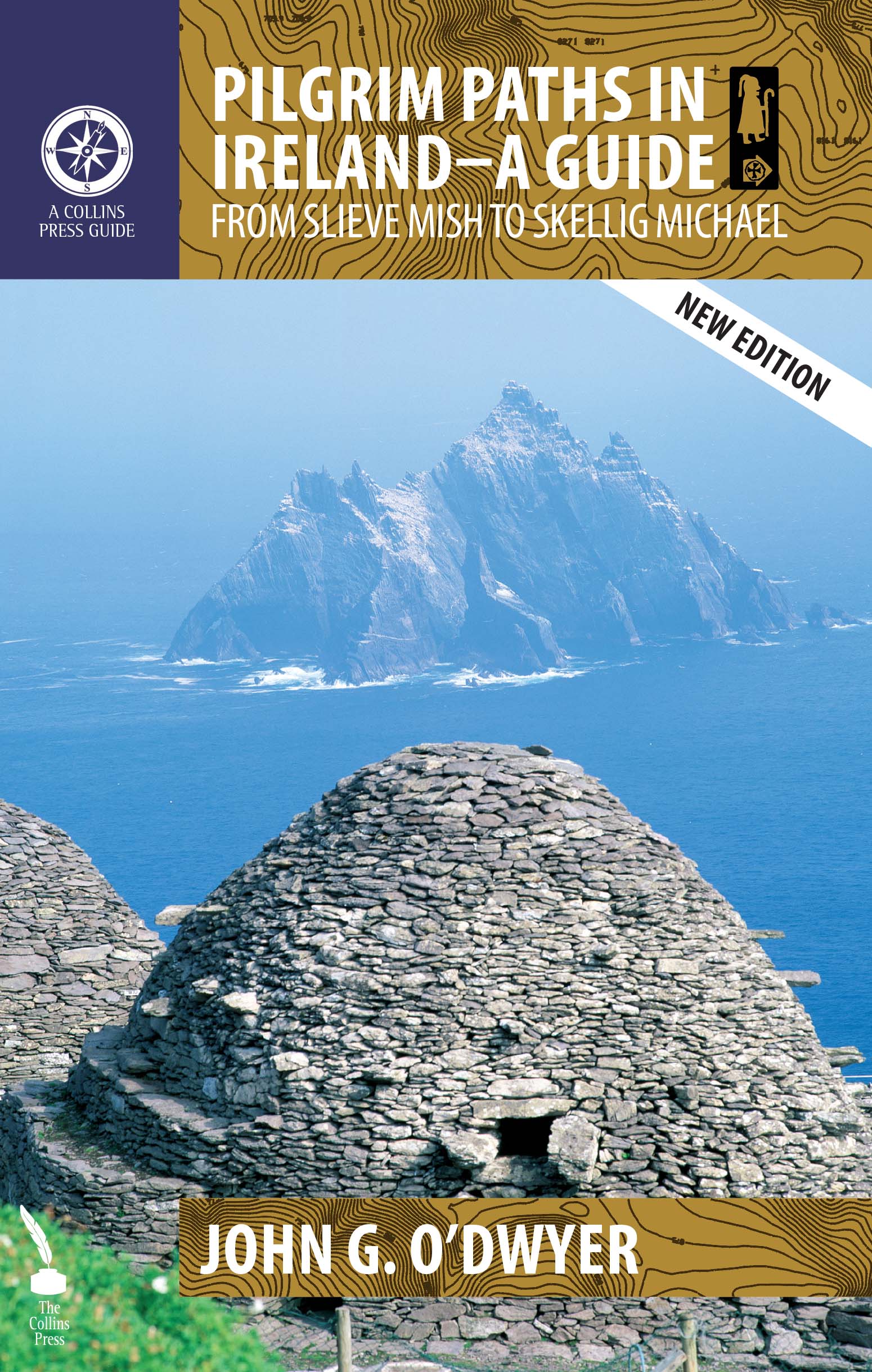

A reflection of Croagh Patrick from Murrisk. (Gareth McCormack)

Overview Map

Irish Pilgrim Passport

The five pilgrim routes that must be completed in order to obtain a Teastas (completion certificate for the Irish Pilgrim Journey) are indicated on the facing page with the symbol:

The routes are the Tóchar Phádraig (route 5 in this book), St Kevin’s Way (routes 9 and 10), Cosán na Naomh (route 15), St Finbarr’s Pilgrim Path (routes 17 and 18) and Cnoc na dTobar (route 19). Fully stamped passports are then forwarded to Ballintubber Abbey, Claremorris, County Mayo to obtain the Teastas.

Information correct at time of writing. See www.pilgrimpath.ie for more details.

Contents

Introduction

1. Slieve Mish (Slemish), County Antrim

2. Lough Derg, County Donegal

3. Slieve League, County Donegal

4. Turas Colmcille, County Donegal

5. Tóchar Phádraig, County Mayo

5. Tóchar Phádraig, County Mayo

6. Croagh Patrick, County Mayo

7. Maumeen, County Galway

8. Clonmacnoise Pilgrim Cycle, County Offaly

9. St Kevin’s Way, County Wicklow: Hollywood to Glendalough

9. St Kevin’s Way, County Wicklow: Hollywood to Glendalough

10. St Kevin’s Way, County Wicklow: Valleymount to Ballinagee Bridge

10. St Kevin’s Way, County Wicklow: Valleymount to Ballinagee Bridge

11. Kilcommon Pilgrim Loop, County Tipperary

12. The Rian Bó Phádraig, Counties Tipperary/Wexford

13. Ardmore Pilgrim Path, County Waterford

14. Mount Brandon Pilgrim Path, County Kerry

15. Cosán na Naomh, County Kerry

15. Cosán na Naomh, County Kerry

16. Mount Brandon Saint’s Road, County Kerry

17. St Finbarr’s Pilgrim Path, County Cork: Drimoleague to Kealkill

17. St Finbarr’s Pilgrim Path, County Cork: Drimoleague to Kealkill

18. St Finbarr’s Pilgrim Path, County Cork: Kealkill to Gougane Barra

19. Cnoc na dTobar, County Kerry

19. Cnoc na dTobar, County Kerry

20. Skellig Michael, County Kerry

Postscript

Waymarking post for Lough Derg Pilgrim Path, County Donegal. (Gareth McCormack)

Introduction

Often I have wondered why it is that rooted within almost every belief system is an ageless tradition of a penitential journey to a place that has been elevated to a higher spiritual plane. Can the reason be that, somewhere deep in our subconscious, pilgrimage serves as a metaphor for life’s bewildering voyage? Certainly, a characteristic of virtually every age is an unshakeable urge to seek deeper meaning and mystical resonance by travelling to some distant place which past generations have vested with enhanced spirituality and redemptive powers.

Medieval pilgrims would have needed this urge in abundance to complete the great penitential paths of their time, for in those far-off days, mechanised transport had yet to effectively kill off the concept of distance. Nevertheless, history informs us that huge numbers of these early wanderers found the motivation to follow the great redemptive trails of the Western World. They journeyed to Rome, Palestine, Canterbury, Lough Derg and the shrine of St James at Compostela in north-western Spain, along with a host of other lesser-known sites.

These arduous excursions into what must then have been a scarily unknown world have long fascinated me since they were undertaken without what have become the unquestioned modern prerequisites of travel insurance, smart phones and GPS systems. Passports were also unknown and so most pilgrims just carried a letter of credentials from a bishop or abbot establishing that they had received the sacraments before leaving and were journeying in a spirit of genuine penitence. A lucky few might possess sufficient wealth to complete their redemptive expedition on horseback or by taking passage on a ship from ports such as Venice or Southampton but mostly pilgrims just walked and walked. Counting calories was not, we can safely assume, the prime concern for these medieval sanctity seekers as they toiled on relentlessly through unmapped and often hostile lands.

Strangers journeying in strange lands, they would have been out of touch with home for up to a year and mostly in areas where people spoke indecipherable foreign tongues. Regularly, they must have felt isolated, lonely and vulnerable to robbery, kidnap and even murder. And yet, whether motivated by escaping damnation or gaining eternal reward, they persisted, driven on each day by the hope of reaching the sanctuary of a monastery or an inn and thus avoiding the dangers of spending a night in the open. And it was not just the common people who went on pilgrimage, for escaping hellfire proved a great medieval leveller. King Henry II of England undertook a redemptive journey to atone for the murder of Thomas à Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, while Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV went barefoot to the Italian town of Canossa to beg Pope Gregory VII to repeal his excommunication.

The Middle Ages were the glory years of mass pilgrimage. Indulgences didn’t come cheap and there was money, power, prestige and, of course, genuine piety bound up with the penitential industry. Small wonder then, that access to pilgrim sites was considered crucially important to the Western Church and that a succession of medieval pontiffs ordered a series of bloody crusades to the Holy Land aimed at wresting back Jerusalem and the holy places from Islamic conquerors.

Historians are now as one in telling us that the coming of the Reformation represented a watershed for Western Europe by breaking forever the power of the monolithic Roman Church. To this day, the enduring impression we have of Martin Luther and his fellow reformers is that they were unswervingly sincere in their beliefs but – shall we say? – not exactly the life and soul of a party. Unsurprisingly then, this rather severe and pragmatic bunch were little given to grand gestures. Believing that salvation could more satisfactorily be accomplished at home and, perhaps, also suspecting that pilgrims might slyly try to incorporate some pleasures of the flesh into their redemptive odysseys, they immediately sent a spanner clattering into the smoothly oiled workings of the redemptive walks industry.

Expressing opposition to the idea that sins could be forgiven by a long excursion of atonement, the reformers did much to lessen the medieval tradition of faith-based redemptive travel. But in the end it was rapidly changing events that overwhelmed the pilgrim ideal. Political instability and a series of long-drawn-out wars eventually led to the virtual elimination from northern Europe of the traditional long-distance spiritual journey.

It seems, however, that the basic human yearning to seek deeper meaning from a transformational journey could not be denied for long and it eventually resurrected itself in a new wave of travel to Marian shrines that was facilitated by relatively stable political conditions in the nineteenth century and the growth of mass transportation. It all began, rather improbably, in the small and then virtually unknown French town of Lourdes in 1858. Here, reports of Marian apparitions to Bernadette Soubirous, an illiterate peasant girl, immediately brought in hordes of devotional tourists and created a welcome spending boom for this once poverty-afflicted area, which continues to the present day.

In the following years Marian apparitions in several underdeveloped areas of Europe transformed local economies: in rural Ireland, Portugal and Bosnia, with appearances at Knock in 1879, Fatima in 1917 and Medjugorje in 1981. The pilgrims that still bring badly needed spending to these locations are for the most part unswervingly devout, Roman Catholic, and solely concerned with the destination itself rather than the redemptive journey. They come in great tidal waves each summer seeking physical, spiritual and emotional healing. Unlike medieval pilgrimage, where the tradition of walking arose from necessity, modern Marian pilgrims rarely – if ever – come on foot. Instead they use trains, automobiles and planes and mostly seek comfortable accommodation in guesthouses and hotels.

The past, of course, never completely dies but sooner or later comes back to catch up with us. So the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have been notable for a movement away from destination-driven penitential travel towards heeding the ageless siren call of the long walk to an evocative place of sanctity. Every second walking enthusiast we meet nowadays seems to be off seeking the allure of the sacred or, perhaps, just chasing some personal goal along an ancient pilgrim path. Footing it may no longer be a necessity, but in recent years huge numbers of otherwise staunchly pragmatic people have suddenly come down with pilgrim-trail fever. In many ways the journey itself has now become the objective; the sought-after personal renewal comes not so much from the destination as from the walk itself. People search for the elusive butterfly of fulfilment and self-awareness by heading for Iona in Scotland, Canterbury in England and along the Via Francigena to Rome. Above all else, however, they are discovering a New Jerusalem on the Camino or Way of St James – a fishing net of paths all leading to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain.

Having never previously completed a pilgrim trail for redemptive reasons, I have, nonetheless, pondered for some time their startlingly increased popularity in modern times. Are pilgrims discovering their two feet once again, as many would have us believe, for deeply spiritual reasons? Or do they merely wish to appreciate the true scale of the landscape and the immense simplification of life that comes with long-distance walking? Then, at the destination, do they feel some profoundly rewarding but non-spiritual right to be there, which they have hard earned in blisters and sweat?

Answering these questions seems in many ways like trying to know the unknowable. Indeed, pilgrims are often unable to rationalise even their own motivation for completing a penitential path. One thing is certain, however: redemption-driven travel to Ireland has – regardless of its often-indecipherable inspiration – a long tradition. Early Christian scholars came to Clonmacnoise, medieval penitents to Lough Derg and Glendalough, while others sought heightened spirituality by visiting Skellig Michael or climbing Croagh Patrick.

But what of today? Are Ireland’s pilgrim paths and sacred mountains still echoing with the footfall of those yearning for some undying truth, or on the other hand, are they merely populated by seekers of gym-slim torsos? Starting at Slieve Mish, where many believe Christianity in Ireland had its first dawning, and finishing where once the known world ended on Skellig Michael, my aim is to ramble the ancient pilgrim paths of Ireland to see if they still resonate with the mysticism of the past for 21st-century pilgrims.

1

Slieve Mish (Slemish) | County Antrim

Overview A short but enthralling route to a summit that offers dreamy views over the mythical north-east of Ireland. Croagh Patrick seems to have cornered the market as St Patrick’s devotional mountain, however, for there is little to represent the reputedly strong links between this striking eminence and Ireland’s national apostle.

Suitability Be warned: the route described is short but quite steep in places and slippery where wet. It requires the skills of easy-grade scrambling to overcome some of the difficulties on ascent and descent, while the path is ill defined in places. Boots should be worn and walking poles could be of some help during the descent.

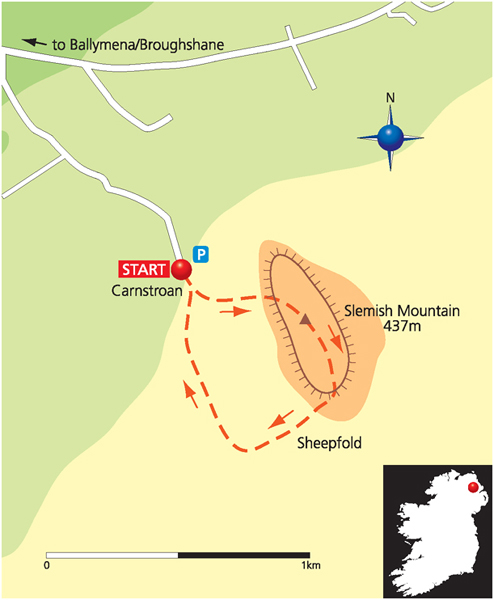

Getting there From the Ballymena bypass take the A42 to Broughshane; Slieve Mish/Slemish is well signposted from Broughshane. The start/finish is at the car park north of Slieve Mish at D217 057.

Time Allow a little over an hour of actual walking time to complete both ascent and descent.

Distance The route is about 2km and involves an ascent of 200m.

Map OSNI Discoverer Series 09 Ballymena/Larne.

Slieve Mish

When I began putting it around that I was off to explore the ancient pilgrim paths of Ireland for my next book, I knew people would find it hard to get their heads around it. Among the choice responses were ‘What, you a pilgrim?’, ‘But that’s a religious book, isn’t it?’, ‘I didn’t think we had any of those,’ and ‘Are you walking to Spain?’

Despite such mystified incomprehension, I soon found myself ready for the off in Belfast. And, indeed, I was glad to start my pilgrim itinerary in this youthful red-brick city compressed between hill and lough. Ever since my first visit, I have always liked this friendly but unfathomable, up-front but enigmatic, metropolis.

On my arrival, there is much hoopla about the recent opening of a huge, £97 million visitor centre aimed at rebooting Northern Irish tourism by commemorating the ill-fated Titanic, which was built in the Belfast shipyards. I check into the Park Inn Hotel, one of the shiny new hostelries that now populate the once-dilapidated city centre.

Bright and early next morning, as I drive north towards Northern Ireland’s bible belt, it immediately strikes me how attractive but underappreciated the Ulster countryside really is. This isn’t, perhaps, surprising in a province that has really only made international headlines for the renown of its writers and the doughty persistence of its urban rioters.

Panoramic view of the basalt plug of Slieve Mish. (Gareth McCormack)

The Antrim hill that will forever be associated with St Patrick lies about 35 miles north of Belfast and is the focal point of an annual Patrician pilgrimage on St Patrick’s Day and so it is first on my list of pilgrim routes. Acutely conscious that I am an unreconstructed sinner now following the saint’s road, I switch on the car radio to distract me from this uncomforting fact. A surprisingly vehement debate is taking place on a local station about the age of the Giant’s Causeway. Northern Ireland’s most renowned visitor attraction and a World Heritage Site is, apparently, about to get a spanking new £18.5 million visitor centre and the discussion is going something like this: the first speaker points out that all mainstream scientific opinion holds that the causeway was formed 60 million years ago by cooling lava. ‘No, it wasn’t, it was created 6,000 years ago,’ is the reply. ‘It can’t be; it’s the result of a volcanic explosion and Ireland had no active volcanoes 6,000 years ago.’ ‘It wasn’t a volcano; it was created by God when he made the world,’ is the response. ‘How can you be sure of that?’ interjects the presenter. ‘It says so in the bible, that’s the infallible word of the Almighty.’ ‘But you can’t take the bible so literally. What about Jonah being swallowed by a whale and Noah building an ark big enough …’ ‘A whale can swallow a man if it’s the will of God.’ ‘I feel an urge to ring the station and point out to the protagonists that they are both completely wrong. In school I remember clearly being told many times that the Giant’s Causeway was built as part of a bridge to Scotland by Ireland’s pre-Christian strongman, Finn McCool.

On the Ballymena bypass, the steep, unmistakeable prominence of Slieve Mish – called Slemish on maps – is obvious to my right. Initially, taking the A42 to Broughshane and then following the directional signs, I note the neatly appointed, prosperous-looking farms, which always appear to contrast strongly with the south, where many farmsteads seem to wallow in a permanent state of benign neglect.

Eventually I fetch up at the trailhead car park. Whether they believe the Giant’s Causeway arose from volcanic action 60 million years ago or was created by the Almighty six millennia ago, Slieve Mish is undoubtedly popular among local people – there are ramblers and family groups already either heading to or returning from the summit. I get little sense, however, that it was from here the spark was ignited that ultimately sent the Christian message sweeping across Ireland. There are no repentant pilgrims in evidence, no stalls selling St Patrick statues, no hazel sticks for rent. Instead, everyone seems focused on exercise or leisure and not at all overawed by the fact that they are following in the footsteps of the world’s most renowned national apostle.

In truth, of course, the early life story of Patrick is almost impenetrably hazy, based mainly on stories and mythologies. According to tradition, Patrick was the son of a wealthy Roman Christian in Britain. In AD 401, at the age of a sixteen, he was captured and sold into slavery to Milchu, a landowner residing in Antrim’s Braid Valley. Perhaps he first came to understand the powerful symbolism of high places when he worked for six years as a herdsman on the slopes of Slieve Mish. In any case, he experienced a profound religious epiphany while tending flocks, which compelled him to alter his destiny. He came to believe God was calling him to convert the Irish people to Christianity. This motivated him to escape from Ireland and in later years return as a bishop and missionary.

One of the best known Patrician mythologies holds that soon after his arrival back in Ireland, Patrick, with heroic indifference to the rituals of royalty, defied Laoghaire, the High King of Ireland, by ascending the Hill of Slane and lighting the first Pascal fire in advance of Laoghaire’s lighting of the Bealtaine fire on the Hill of Tara. Surprising as it may seem, this apparently petty and foolhardy act of defiance had the effect of igniting a bush fire that raced with the speed of a tsunami across Ireland. So impressed was Laoghaire by Patrick’s audacity that he immediately allowed him a free hand to carry the Christian message throughout the length and breadth of Ireland.

View from the summit of Slieve Mish over the main car park and visitor centre.

So Patrick went on his missionary way and soon after was scrambling up the Rock of Cashel to baptise the King of Munster, while also reputedly finding time to establish a monastery atop Ardpatrick hill in County Limerick. Tradition also holds that he blessed a well after spending a night high in the Maumturk Mountains and finally that he fasted for forty days on Croagh Patrick’s summit.

In those days, people walked only out of necessity and Patrick would not have undertaken these ascents lightly or for leisure purposes. He clearly understood the powerful imagery associated with the most elevated locations, and was aware of their unmatched ability to evoke the necessary reverence and awe required to reinforce the impact of his message.

If he lived today it would be easy to imagine modern-day management experts breaking into jargon to describe him as a ‘charismatic change-agent and transformational leader, who succeeded by using reverence for high places to position a user-friendly and well-targeted belief system in a pagan society’.

It is, of course, almost inconceivable that St Patrick was the first Christian missionary to Ireland in the way it is unlikely that Christopher Columbus was the first European to reach America. After all, the Roman Empire had been Christianised for over a century before Patrick, and Ireland had strong trade links with Roman Britain. Nevertheless, a simple narrative is often the most effective: the early Irish Church cannily rescued Patrick from obscurity and, in a series of hagiographies, credited the saint alone with converting Ireland to Christianity. So, while other missionaries have long been forgotten, Ireland’s apostle lives on as one of the world’s best-known, most commemorated and commercially exploited saints.

Initially, the Slieve Mish path leads upwards at a sympathetic angle. Soon, however, the smooth grasslands are behind and I find myself scrambling skywards over disobliging basalt but the advantage of a steep gradient is, however, that height comes rapidly. Unlike a Kerry hill, where an ascent that appears like an hour invariably takes two, Slieve Mish relents with surprising ease. Having mentally estimated an hour to the top, I then take silly pleasure in the fact that I am on the summit plateau in half that time. Swinging right along the broad whaleback eminence, I reach the bare stones of the summit and marvel at the magnificent 360-degree views with the sleeping giant of Cave Hill lying sentinel above Belfast Lough to the south. Northwards is the great sweep of the Antrim plateau and beyond Ireland’s most evocative coastline is the gleam of the ancient Sea of Moyle. This is where the Children of Lir reputedly spent 300 years, having been transformed into swans by – you guessed it – a wicked stepmother, before her spell was broken by the arrival of Christianity, brought by – no need to guess this time – St Patrick. It is a timeless vista bounded by the misty outline of distant Scottish mountains. Here, although you would find it hard to believe, I am standing at the heart of Ireland’s second most populated county. And yet, all I need is a small stretch of the imagination and pre-Christian farmers are once again tending their flocks in the valleys below.

Atop some ageless stones I sit back and allow time to drift by in slow motion – as Patrick may have done on sunny days more than a millennium and a half previously. Perhaps it was in a moment such as this that he experienced his mystical epiphany. But God is apparently otherwise engaged, for there is to be no ‘road to Damascus’ moment for me.

I do conclude, though, that Slieve Mish is not in any sense a pilgrim destination and that Croagh Patrick has clearly established itself as the market leader with regard to Patrician tourism. Apart from a very brief description of St Patrick’s association with Slieve Mish on a storyboard in the car park, the mountain lacks the summit shrine that would offer a necessary focal point for a redemptive journey. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, for many believe St Patrick spent his Irish captivity not in Antrim but in North Mayo. But then, the Camino pilgrim route brings hundreds of thousands of walkers to Spain each year in honour of St James even though there is no evidence whatsoever that the saint ever visited the Iberian Peninsula during his lifetime.

Then it occurs to me that if this iconic hill were located somewhere in the south of Ireland, and not in the deepest heartland of non-conformist Ulster, somebody would surely have lugged up at least a Holy Year cross by now and, perhaps, also a statue of St Patrick, hands raised in magisterial blessing. As it is, however, my only company on the summit is a family group and a few power walkers who sashay past with ‘miles away’ stares while safely cocooned from the world by their iPods.

Eventually, the call back to the twenty-first century becomes too strong to ignore. Rousing myself reluctantly, I continue west with the lordly Sperrin Mountains dominating the skyline. Where the plateau disappears into a steep, rocky descent, I swing right and downhill to follow a precipitous and informal track that again demands some scrambling skills to ensure a safe descent. Once back on the lush, green sward, however, the going becomes straightforward and enjoyable. Now it is just a question of savouring the unseasonably warm early summer sunshine on the short ramble back to the car park.

2

Lough Derg | County Donegal

Overview In the best pilgrim tradition, this route is far removed from roads, houses and other signs of modern life and has many echoes of its pilgrim past along the way. This makes it a great way of escaping the present for a few hours without the inconvenient effort of climbing to a mountaintop.

Suitability Easy route following well-maintained forest tracks with nothing that could really be referred to as a hill along the way. No special hillwalking skills required while following pleasant paths well suited for casual ramblers.

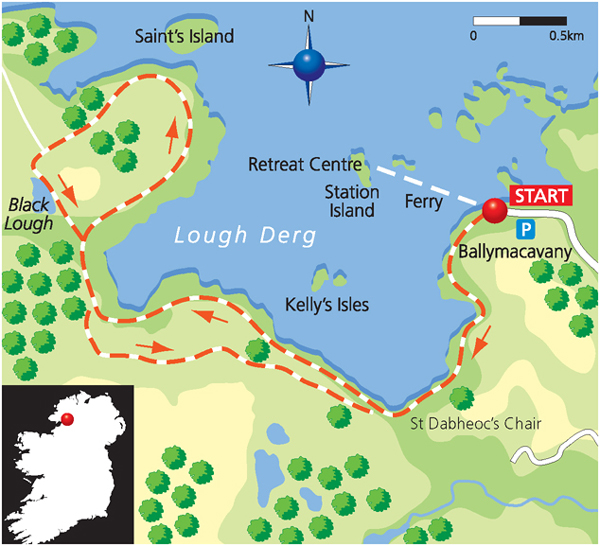

Getting There From Pettigoe, which lies on the Fermanagh/Donegal border, follow the R233. This leads directly to Station Island pier (G091 739) where pilgrims are processed before travelling by boat to Station Island.

Time About 3 hours.

Distance 12km approx.

Map OSi Discovery Series 11 – but you won’t need it as the route is clearly marked.

Lough Derg

It is sometimes said that paradise is likely to prove disappointingly non-exclusive because everyone ultimately wants to go there. The first thing I discover on arrival at the suitably isolated Lough Derg Reception Centre is that purgatory is also a startlingly popular 21st-century destination. People are not only queuing to go, they are also busy using the self-service check-in machines to speed up their arrival at what is generally regarded as the toughest redemptive exercise in Christendom.