This title is also available as an e-book.

For more details, please see

www.wiley.com/buy/9781118815175

Edited by

This edition first published 2018

© 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permision to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Jacqui Finch and Helen Dutton to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Offices:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester,

West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office:

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting scientific method, diagnosis, or treatment by physicians for any particular patient. The publisher and the authors make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. Readers should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organisation or website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organisation or website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this works was written and when it is read. No warranty may be created or extended by any promotional statements for this work. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any damages arising herefrom.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Finch, Jacqui, 1961- editor. | Dutton, Helen, editor.

Title: Acute and critical care nursing at a glance / edited by Jacqui Finch, Helen Dutton.

Description: Hoboken, NJ : Wiley, 2017. | Series: At a glance series |

Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017012986 (print) | LCCN 2017014342 (ebook) | ISBN

9781118815151 (pdf) | ISBN 9781118815168 (epub) | ISBN 9781118815175 (pbk.)

Subjects: | MESH: Emergency Nursing—methods | Critical Care Nursing—methods

| Handbooks

Classification: LCC RC86.8 (ebook) | LCC RC86.8 (print) | NLM WY 49 | DDC

616.02/5–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017012986

John Wiley & Sons Limited is a private limited company registered in England with registered number 641132. Registered office address: The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom. PO19 8SQ.

Cover image: © simonkr/Gettyimages

Cover design by Wiley

Sharon Elliot Chapters 8, 9, 37

Head of Pre-registration

University of West London, London, UK

Adrian Jugdoyal Chapter 55

Hepatology Advanced Nurse Practitioner

Northwick Park and St Mark’s Hospital;

Associate Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Catherine Lynch Chapter 54

Senior Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Carl Margereson Chapters 11, 12, 53

Senior Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Caroline Smales Chapters 4, 32

Senior Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Sharon Smith Chapters 14, 26

Senior Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Renata Szczecinska Chapters 21, 30, 31, 38

Cardiac Practice Development Nurse

King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Associate Lecturer

University of West London, London, UK

Dean Whiting Chapter 44

Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Trauma and Orthopaedics

Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust;

Honorary Senior Lecturer in Trauma Science

Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London, London, UK

Suzanne Whiting Chapter 43

Burn Care Advisor for the London and South East Burns Network

Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, UK

With grateful thanks to our academic and clinical colleagues who willingly shared their ideas, knowledge and experience to help in shaping many of the chapters in Acute and Critical Care Nursing at a Glance

Victoria Allen Chapter 35

Senior Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

Kate Bradley Chapters 10, 20

Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

Barry Hill Chapters 46, 47, 48

Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

John Mears Chapters 5, 51

Senior Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

Lyndsey Mears Chapter 56

Senior Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

Trisha Mukherjee Chapters 28, 35

Modern Matron: Intensive Care

The London Northwest Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

Madhini Sivasubramanian Chapter 37

Lecturer, University of West London, London, UK

Liz Staveacre Chapters 1, 18

Senior Sister: Critical Care Outreach

The London Northwest Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

In 2000, the UK Department of Health’s publication the Comprehensive Critical Care – A Review of Adult Critical Care Services classified patients according to the severity of their illness. This led to the concept of ‘critical care without walls’, identifying the presence of acutely unwell patients outside the Intensive Care Unit and acknowledging that specialist nurse education and training in recognition and preliminary management of acute deterioration, was now required in all areas of clinical practice. Since that time, society’s growing, diverse and ageing population has augmented this need and an ever increasing use of technology in care settings has meant that practitioners are frequently required to plan, implement and evaluate care for patients with complex, multiple problems in a variety of clinical settings. Certainly, the expansion of community services has meant that many patients are successfully managed outside the hospital. However, the centralisation of acute services in healthcare, especially for emergency medicine, has seen a huge demand for in-hospital bed capacity in some areas. This has led to the increasing development of a wide range of assessment units designed to manage large numbers of patients presenting to hospital with acute problems. Over recent years the development of critical care outreach teams and the birth of track and trigger systems all assist with this, but there still remains a great need for nurses to further develop their assessment skills and their ability to promptly and appropriately respond to worsening clinical scenarios and life-threatening events. The 2015 Nursing and Midwifery Council Code of Conduct clearly states that registered nurses and midwives must, at all times, ‘preserve safety’. Whilst acknowledging the limits of their competence, they have to be able to assess accurately the patients in their care, taking account of current evidence and knowledge and demonstrate the ability to make timely referral. Failure to achieve this standard is failure to act in the patients’ best interests.

It has been suggested that nurses may possess differing perspectives on what clinical deterioration actually is. This may be irrespective of the scoring systems that exist to assist them and, of course, the tools themselves are sometimes subject to misinterpretation and misuse. One way to address this is to revisit the basic principles of normality and abnormality when considering how a patient might present, systematically collecting subjective and objective data in order to recognise when problems are occurring. Development of sound clinical reasoning like this, strongly founded in evidence-based knowledge, will vastly contribute to the provision of quality care, ensuring patient safety both now and in the future.

The chapters in the book are structured according to the systematic ABCDE framework.1 This emphasises the priorities of care when faced with an acutely unwell patient and use of the ‘at a glance’ approach greatly facilitates this with its focus on immediacy. To complement this, in each chapter the text and accompanying diagrams present key information in a concise format, using current evidence gathered from local, national and international policies, protocols and guidelines. In addition, the inclusion of patient case studies and multiple choice questions covering a range of specialist content also serve to highlight significant issues in practice, enabling consolidation of learning by way of self-assessment. In summary, we hope this book will be a good reference source for our readers (be they registered or student practitioners), fostering their critical thinking. We also hope, in the interests of evidence-based quality care, that it creates a desire in our readers to learn more about critical care and that this knowledge is used to teach and support others who are providing care to the acutely ill.

Helen Dutton

Jacqui Finch

Aorta

Airway, breathing, circulation, disability circulation

Arterial blood gas

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

Advance care plan

Acute coronary syndrome

Adrenocorticotrophic hormone

Antidiuretic hormone

Acute exacerbations of COPD

Atrial fibrillation

Acute kidney injury

Adult advanced life support

Acute myocardial infarction

Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last ate and drank, Events leading (to injury)

Abbreviated Mental Test Score

Aseptic non-touch technique

Autonomic nervous system

Angiotensin receptor blockers

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Airway, tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, massive haemothorax, flail chest, cardiac tamponade

Adenosine triphosphate

Atrioventricular

Atrioventricular node

Alert, voice, pain, unresponsive

Blood–brain barrier

Bi-level positive airways pressure

Body mass index

Basal metabolic rate

B-type natriuretic peptide

Blood pressure

Cardiac arrest

Calcium ion

Coronary artery bypass grafting

Confusion assessment method: Intensive care unit

Community-acquired pneumonia

Congestive cardiac failure

Critical care outreach team

Chronic heart failure

Cardiac output

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Continuous positive airways pressure

Cardiopulmonary bypass

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Care Quality Commission

Catheter-related blood stream infection

Chronic respiratory failure

C-reactive protein

Capillary refill time

Cerebrospinal fluid

Computed tomography

Computerised tomographic pulmonary angiography

Confusion, urea, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure (age ≥65)

Cerebrovascular accident

Central venous catheter/cardiovascular centre

Central venous pressure

Chest X-ray

1- deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin

Diabetes insipidus

Direct non-invasive automated mean arterial blood pressure measurement

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Do not attempt to resuscitate

Deep vein thrombosis

Electrocardiogram

End positive airways pressure

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatogram

Expiratory reserve volume

Endotracheal tube

Early warning systems

Foreign body airway obstruction

Forced expiratory volume in one second

Functional residual capacity

Forced vital capacity

Gabba amino butyric acid

Generalised anxiety disorder assessment

Glasgow Coma Scale

Glomerular filtration rate

Gastrointestinal

Glyceryl trinitrate

Hydrogen ions

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Bicarbonate ion

Healthcare-associated infection

High dependency unit

Heart failure

High flow nasal cannula

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar syndrome

Heat and moisture exchanger

Heart rate

The ratio of inspiration to expiration

Implantable cardioverter

Intracranial pressure

Intensive care unit

Inspiratory positive airways pressure

Intravenous

Jugular venous distension

Jugular venous pressure

Potassium ion

Laryngeal mask airway

Low molecular weight heparin

Level of consciousness

Lasting power of attorney

Left ventricle

Left ventricular failure

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction

Muscarinic receptors

Mean arterial pressure

Magnesium ion

Magnesium sulphate

Myocardial infarction

Manual in-line stabilisation

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

Magnetic resonance imaging

Malnutrition universal screening tool

Sodium ion

Name, age, time of injury, mechanism of injury, injuries sustained, signs and symptoms, treatments given

Nasal cannula

National Early Warning Score

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction

Nasopharyngeal airway

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Oropharyngeal airway

Pulmonary artery

The partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia

The partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood

Patient-controlled analgesia

Percutaneous coronary intervention

Proximal convoluted tubule

Pulmonary embolism

Positive end expired pressure

Peak expiratory flow

Peak expiratory flow rate

Parasympathetic nervous system

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Personal protective equipment

Pressure support

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax

Quick Sequential (Sepsis Related) Organ Failure Assessment

Right atrium

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

Rapid eye movement

Return of spontaneous circulation

Respiratory rate

Residual volume/Right ventricle

Sinoatrial node

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

Situation, background, assessment, recommendation

Systolic blood pressure

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH

Sympathetic nervous system

Site, onset, character, radiation, associated symptoms, time course, exacerbating and relieving factors, severity

Secondary pneumothorax

Oxygen saturation of peripheral capillary blood

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

Selective Serotonin re-uptake inhibitor

ST elevation myocardial infarction

Superior vena cava

Stroke volume

Systemic vascular resistance

Supraventricular tachycardia

Total body surface area

Transient ischaemic attack

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

Trans intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

Ventilation/perfusion

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

Venous blood gas

Minute ventilation

Ventricular fibrillation

Visual infusion phlebitis

Tidal volume

Ventricular tachycardia

Venous thromboembolism

White blood cells

White cell count

World Health Organization

Work of breathing

The last decade has seen a change in the environment in which care of the acutely unwell patient is delivered. Nurses working in acute care areas are increasingly exposed to patients who require more detailed assessment and monitoring. Nurses need to be competent in the skills required to care effectively for critically ill patients.

The general population is ageing, with those requiring hospital admission older, sicker and generally more dependent. In 2010 the over-65 age group accounted for 10 million of the population in the UK, and by 2030 the number will be closer to 15.5 million. Emergency admissions for patients who have increasingly complex comorbidities requiring multidisciplinary and cross-speciality input are increasing. Meanwhile, greater emphasis has been placed on managing patients in their home environment for longer periods, meaning those who are admitted to hospital are sicker and require greater use of resources. Technological developments in healthcare means that treatments once thought too high a risk are now commonplace in hospitals.

With the increase in patient acuity it became evident that wards were not always able to cope effectively with the extra demands placed on them. Studies in the late 1990s identified that the deteriorating patient was not always recognised, and/or sufficient action was not taken prior to admission into the intensive care unit (ICU), adversely affecting patient outcome.

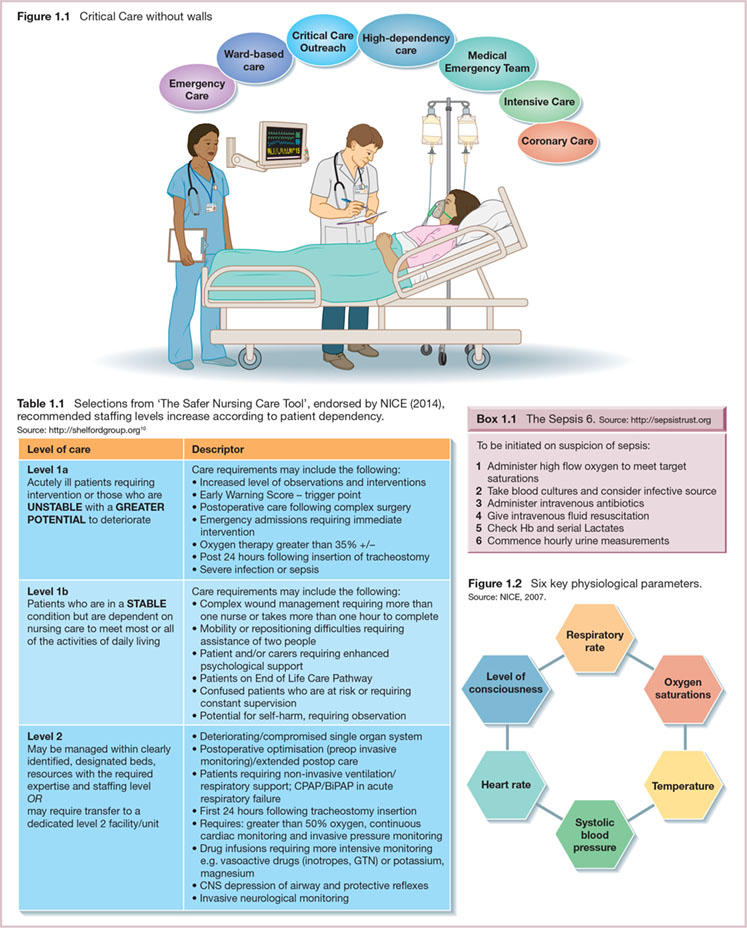

In 2000 the Department of Health1 published its report, Comprehensive Critical Care, recommending a systems approach was taken to deliver care for patients during acute and critical illness, and in the recovery period. Critical care emerged as a new speciality, addressing the severity of patient illness, regardless of their physical location within the hospital. The Department of Health introduced the concept of ‘critical care without walls’, to ensure acutely unwell patients nursed in a variety of environments, from ward-based care through to intensive care, come under the ‘critical care umbrella’ (Figure 1.1). A spectrum of dependency levels from levels 0 to 3, were outlined to encompass all those requiring critical care:1

Workforce development, to ensure that staff caring for potentially critically ill patients receive education and training, is essential.2 Key clinical competencies to be achieved have been identified.3 Registered nurses are accountable for all aspects of care, even those tasks often delegated to others, such as the taking and recording of observations.4

The Intensive Care Society (2013) and others published core standards for organisation of intensive care units (levels 2 and 3) and recommended safe staffing levels.5 As acutely unwell patients are nursed across a range of environments, there are challenges for the provision of safe staffing levels on acute wards, which have been highlighted by the Francis Report (2013).6 NICE (2014) issued guidance for safe staffing for nurses in acute hospitals supporting ‘The Safer Nursing Care Tool’ (Table 1.1).2 This tool is based on the Department of Health classification, but adds an additional level, 1b, acknowledging the differing demands on nursing care activities, such as supporting the patient at risk of self-harm. It is designed to inform nursing establishments to be planned, linked to patient acuity both in ward-based care and critical care units.

Cardiac arrests are predictable and preventable. Survival to discharge post cardiac arrest is as low as 15%.7 Early recognition of deterioration is the first step in the chain of survival. Almost half of patients who die without a ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) order have serious, potentially reversible abnormalities in their vital signs in the 24 h preceding death. In fact, slow, progressive physiological deterioration with unrecognised and inadequately treated hypoxaemia and hypotension, can often be seen prior to admission to ICU and leads to poor survival. Delays in time to treatment have a profound effect on patient outcome. Specific intervention and timely instigation of organ support, via a medical emergency team or critical care outreach team (CCOT), is more important than getting the patient to the ICU.

Critical care outreach teams have evolved to provide expert input outside the environment of intensive and high dependency units. They aim to avert or ensure timely admissions to critical/intensive care and share critical care skills across the multidisciplinary team. Implementation of early therapies, for example, high flow oxygen, fluid resuscitation, or care bundles such as the ‘Sepsis Six’ (Box 1.1) can improve mortality and reduce rates of cardiac arrest. The CCOT’s role in sharing critical care skills, improving early recognition of deterioration, has empowered nurses to escalate care appropriately and is now a widely adopted approach to maintaining patient safety.

Recommendations to improve the recording of six key physiological observations (Figure 1.2), include the use of multiparameter Early Warning Scores to help identify patients at risk and escalate care appropriately.8 The National Early Warning Score (NEWS)9 (see Chapter 3) is a well-validated tool in the recognition and prevention of deterioration, and is now used widely in acute care trusts throughout the UK. Acutely unwell patients require competent and confident nurses to interpret clinical signs, recognise risk of deterioration and escalate care to the appropriate healthcare professional, ensuring senior medical input occurs in a timely manner to optimise patient outcome.

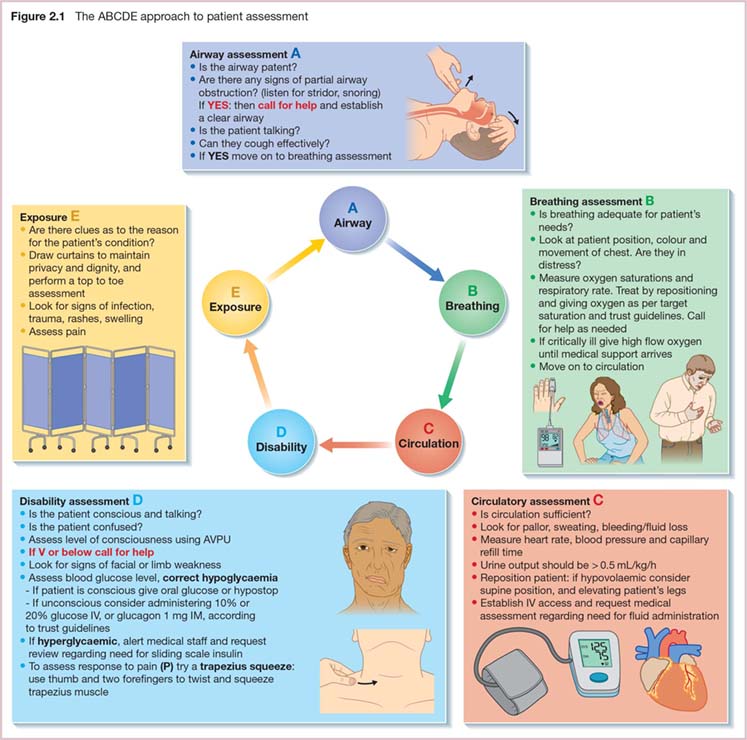

Most people in hospital are unlikely to become seriously unwell. If they should deteriorate, early detection through a detailed clinical assessment is essential so that nurses are able to identify the problem and ensure that appropriate care and treatments are given in a timely manner. When caring for an acutely unwell patient, the use of the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach helps keep the focus on those aspects of deterioration that are most likely to be life threatening, thereby improving patient outcome. This chapter gives an overview of each area, but these are also considered in more detail in later chapters.

The ABCDE approach (Figure 2.1) is an excellent clinical tool for the assessment and treatment of patients who are acutely unwell.1 This approach dictates that each element is assessed, then treated as necessary, before moving on to the next element. Early recognition and treatment of abnormal physiology in this progressive fashion initiates effective treatment, preventing further deterioration, whilst help can be sought from clinicians with specialist expertise. The process is used to reassess progress as treatments are instigated. Whilst nurses are familiar with taking and recording vital signs, assessment of the acutely unwell patient requires more detail, taking note and interpreting a range of clinical signs that assist in clinical decision making.

A general impression when first approaching the patient is often the trigger for a more detailed assessment. The patient who does not respond to questions, has collapsed, or is perhaps severely distressed and sweating profusely, has clear markers of serious illness.

The airway is assessed for patency as a priority as airway obstruction is a medical emergency. If untreated it will rapidly lead to cardiac arrest, and so help is required immediately. An alert and chatty patient has a patent airway. A reduced level of consciousness is a common cause of both partial and complete airway obstruction, requiring the healthcare professional to perform the ‘head tilt chin lift’ manoeuvre, to keep the airway open. Partial airway obstruction is noisy, and requires immediate management (see also Chapters 8 and 9). Once the nurse is confident that the patient’s airway is patent, they can move on to assessment of breathing.

Adequate oxygenation is essential. SpO2 monitoring, available in all acute care environments, is measured promptly if deterioration is suspected. SpO2 values outside the patient’s target range (94–98% or 88–92% as prescribed) requires oxygen therapy to restore it to normal or near normal levels (also Chapter 15).2

Indicators of respiratory distress included:

Respiratory rate has been shown to be a significant predictor of risk of deterioration.3 This important observation should be counted for 1 min to ensure accuracy and will normally be between 12 and 20 breaths/min. The chest should be inspected for bilateral equal expansion. Failure of both sides of the chest to move equally on inspiration could suggest a collection of pleural fluid, or a chest infection. If the trachea is displaced from the midline, with unilateral chest expansion and respiratory distress, a medical emergency such as tension pneumothorax, may be present. Urgent medical help is required. A patient who has breathing difficulties should be repositioned in the upright position, given appropriate prescribed therapy promptly (such as oxygen or bronchodilators), and help should be summoned if necessary, before moving on to circulatory assessment.

The circulatory system transports oxygenated blood to the tissues. Patient pallor as a result of vasoconstriction also causes hands and feet to cool if circulation is inadequate. Profuse sweating and changes in level of consciousness are also associated with decreased perfusion. A peripheral pulse should be palpated manually and assessed for rate, rhythm and strength. Any abnormalities should prompt an ECG recording. A fall in systolic blood pressure is a late sign and can be due to problems such as: hypovolaemia, cardiac failure, pulmonary embolism, sepsis or anaphylaxis. Most patients who are hypotensive require fluid therapy (after excluding cardiac causes), so intravenous access should be obtained as necessary. Blood and fluid losses should be noted, considering urine output (which should be greater than 0.5 mL/k/h) and overall fluid balance (see also Chapter 25).

Level of consciousness can be quickly assessed using an AVPU assessment to assesses neurological status (also Chapter 46):

If changes in AVPU are noted then a more detailed assessment using tools such as the Glasgow Coma Score is required. Changes in level of consciousness caused by either hypo- or hyperglycaemia should be treated promptly. Changes in face symmetry, unequal arm movement or speech alterations could indicate brain injury due to a stroke. Patients with deteriorating consciousness need their airway protected by appropriately skilled healthcare personnel.

It is important to maintain patient dignity whilst performing a full body check. Looking ‘under the sheets’ ensures no essential clues are missed. Temperature is an important indicator for infection and may be assessed here, or under circulation. If the patient is pyrexial, look for the source of infection, checking all invasive lines/devices and inspecting wounds and lesions for signs of bleeding, oozing, inflammation or tenderness.

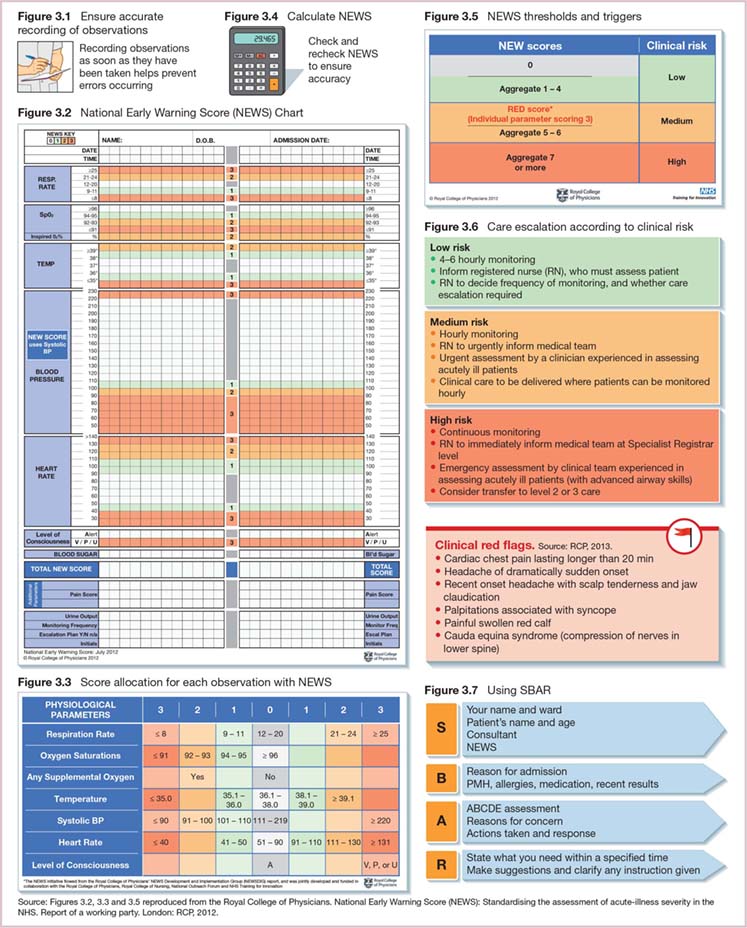

Patients who are admitted into hospital with acute care needs have a right to receive reliable harm-free care. The recognition of clinical deterioration relies largely on nurses taking and recording vital signs, identifying where these are abnormal, communicating findings to skilled clinical personnel and ensuring appropriate interventions are given in a timely manner. Lack of recognition of physiological changes may lead to a delay in care, an extended hospital stay, ICU admission or even a premature death. Failure to rescue occurs when a patient’s deterioration is not recognised and they suffer harm from a potentially treatable condition. Nurses are accountable for ensuring accurate clinical observations are recorded and acted upon (Figure 3.1), even if delegated to a non-registered healthcare professional.1 Training, education and support for the healthcare team is essential in the delivery of harm-free care.

In 2007 NICE recommended the use of ‘aggregated weighted track and trigger systems’.2 These are early warning systems (EWS) that consider a number of different clinical observations, generating an overall score to help evaluate risk of deterioration. The score gained is used to identify low, medium and high scoring groups, thereby determining frequency of observations and the need for review by the medical team and/or outreach. A number of EWS have been used across the UK, leading to a significant variation in trigger levels, and therefore a potential lack of understanding by clinical staff moving across the country to work in different clinical environments. A standardised National Early Warning Score (NEWS) developed by The Royal College of Physicians,3 has been embraced by acute care trusts across the UK. A unified approach helps all clinical staff to understand the level of the risk of deterioration of patients. Using NEWS consists of a number of straightforward steps:

The NEWS chart requires the recording and scoring of the six physiological parameters identified by NICE (2007) namely:2

Trust protocols vary as to whether numbers or dots are used to record observations, but it is recommended that respiratory rate and oxygen saturations are recorded as a number.5 This enables changes in respiratory rate to be more clearly documented, especially when in the red zone at >25 breaths/min. The percentage of oxygen is recorded as either air, oxygen percentage, or in L/min (nasal specs), so response to oxygen therapy can be recorded.

Figure 3.3 identifies scores for each physiological parameter, so there is no confusion between borderline values. For example, a heart rate of 110 beats/min scores 1; using the observation chart alone may not make this clear. The NEWS chart and the threshold and trigger chart have been made into pocket cards by some trusts, aiding accurate and consistent scoring.

An automatic addition of 2 is made to the NEWS if the patient is receiving oxygen therapy, correctly highlighting that the hypoxaemic patient receiving supplemental oxygen is unwell, and is at increased risk of deterioration and death. An alternative trigger range of oxygen saturations for patients who have adapted to chronic disordered physiology such as COPD and are at risk of hypercapnia (target range SpO2 of 88–92%), can be appropriate, but must be clearly marked and signed for by the doctor on the observation chart.

Trigger thresholds will define action to be taken at trust level. NEWS >7 requires urgent action (within 15 min) at senior medical level, support from outreach, continuous observations, with the possibility of transfer to a higher level of care. This is an opportunity to ask the medical team to consider the ‘ceiling of care’ as not all patients benefit from receiving advanced levels of support, such as intubation and mechanical ventilation in an ICU environment.3

Doctors and outreach nurses looking after a large number of patients have competing priorities for their time. Clear, precise and accurate information is needed to enable them to focus on those who are most unwell. NEWS conveys severity of illness. A communication tool such as SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) (Figure 3.7) supports structured communication and good clinical decision making to improve patient outcomes:

The accurate, consistent use of an early warning tool and escalation strategy such as NEWS, and a communication tool such as SBAR, contributes to ensuring care is focused on those patients who are at the greatest risk of deterioration.