This title is also available as an e-book.

For more details, please see

www.wiley.com/buy/9781119043867

This edition first published 2018

© 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Josie Tetley, Nigel Cox, Kirsten Jack, Gary Witham to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

| Registered Offices: | John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK |

| Editorial Office: | 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK |

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting scientific method, diagnosis, or treatment by physicians for any particular patient. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organisation, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organisation, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available

ISBN: 9781119043867

Cover image: © FangXiaNuo/Shutterstock

Cover design by Wiley

Razia Aubdool, Chapters 16 and 17

Canan Birimoğlu, Chapter 15

Louise Bowden, Chapters 16 and 17

Jacqueline M. Cash, Chapter 10

Michelle Croston, Chapter 3

Nigel Cox, Chapters 24 and 38

Donna Davenport, Chapter 25

Jan Dewing, Chapter 26

Garry Diack, Chapter 36

Fiona Duncan, Chapter 8

Chris Ellis, Chapter 9

Marilyn Fitzpatrick, Chapter 41

David Garbutt, Chapter 29

Linda Garbutt, Chapter 2

Robin Hadley, Chapter 34

Carol Haigh, Chapter 8

Caroline Holland, Chapter 43

Maxine Holt, Chapter 14

Lindesay Irvine, Chapters 18, 20 and 39

Kirsten Jack, Chapters 4, 21, 38 and 45

Emma-Reetta Koivunen, Chapters 42 and 44

Janet Marsden, Chapter 7

Jamie McPhee, Chapter 22

Julie Messenger, Chapter 6

Eula Miller, Chapters 27 and 31

Duncan Mitchell, Chapter 36

Gayatri Nambiar-Greenwood, Chapters 1 and 32

Stewart Rickels, Chapters 19 and 40

Caroline Ridley, Chapter 30

Stuart Roberts, Chapter 35

Carol Rushton, Chapter 25

Clare Street, Chapter 5

Stuart Taylor, Introduction

Josie Tetley, Chapters 21, 24, 42 and 45

Lucy Webb, Chapter 37

Danita Wilmott, Chapter 12

Gary Witham, Chapters 11, 13, 23, 28 and 33

This book is primarily aimed at undergraduate and post-qualification nurses who care for older people in a range of care settings including hospital, community, residential and other health or social care settings. The editors and contributing authors believe that this book will also be of value to a wide range of practitioners working in a nursing or a nurse-related capacity, for instance pre-registration nurses, healthcare assistants, associate practitioners, registered nurses working in both the NHS and independent care home sectors, and those returning to a career in nursing.

Nurses are under increasing pressure to demonstrate that the care they deliver is supported by best evidence, compassionate and person-centred. For nurses working with older people this can be challenging, as people’s needs in later life are often complex and diverse. This book therefore provides an accessible overview of key concepts that can help nurses understand how care in practice can be more person-centred, while also promoting dignity, health and well-being.

The book is divided into six parts. Part 1 introduces concepts central to dignified and compassionate person-centred care. Part 2 explores health and well-being, including essential aspects of living such as sleep, the senses and nutrition. Part 3 focuses upon health promotion, and incorporates a diverse range of topics including physical activity and the arts. Parts 4 and 5 address complexity and diversity in older people’s care, including topics such as mental well-being, diverse communities and learning disability. Part 6 concludes the book, and illustrates how environments of care impact on practice. Autonomy and independence are central principles, and the role of assistive technologies and the challenges of working with older people in a diverse range of contexts are considered.

Dignity in care work focuses on the value of every person as an individual. It means respecting others’ views, choices and decisions, not making assumptions about how people want to be treated and working with care and compassion

Skills for Care, 2017

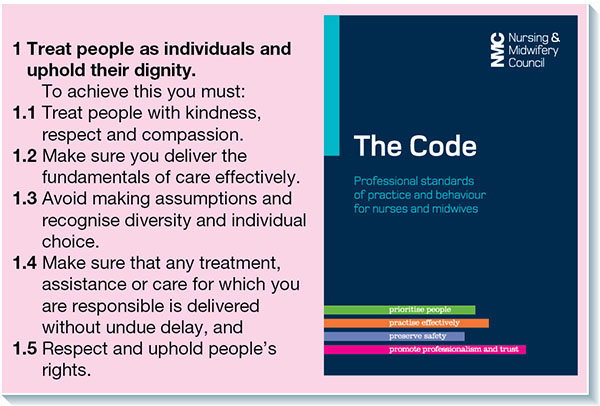

The concept of dignity shapes all of the chapters in this book. However, making dignity in care a reality also means that nurses and other healthcare professionals need to be able to understand what this means in the context of people, places and processes in multiple and complex ways (Figure 0.1). The importance of dignity in care is also underpinned by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) code of conduct (Figure 0.2) which, at the time of writing, states that nurses must:

Figure 0.2 The Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC) code of conduct.

Source: Nursing & Midwifery Council (2015).

When considering dignity-related matters for patients we tend to think of some of the more personal situations such as receiving assistance with bathing, dressing or toileting, but recommendations from Age UK (2013) serve to remind nurses of the need to think widely and creatively about older people’s care. From admission to hospital or any point of care, it is important to develop a professional but caring relationship that takes account of the wider and more holistic needs of older people and their carers. This book provides some practical guidance about how these needs can be met in ways that uphold dignity in care. However, it is also important to remember that understanding and appreciating individual values, beliefs and practices is not easy, and key areas related to dignity need to be considered from the outset of the patient journey (Royal College of Nursing, 2008, 2017); again, key chapters in this book provide guidance about good practice in nursing on this.

The editors and authors who have contributed to the development of this book recognise that there are no easy solutions to providing individualised and dignified care for older people. By providing a range of short, but succinct evidence-based chapters, this book presents guidance about key concepts that can support dignity in care in the context of the key difficulties and challenges that nurses encounter in practice.

Josie Tetley

Nigel Cox

Kirsten Jack

Gary Witham

Stuart Taylor

To provide person-centred care (PCC) for any patient or client means that they are included in decision making about their care. PCC in the older person cannot be successful unless the ethos of the wider MDT is one of a shared partnership with each other and the patient.

In order for PCC to be effective for all concerned, nurses involved in caring for the older person need to be aware of a number of factors. This involves not only looking at the needs of the patient and considering their definition of satisfaction, but also, fundamentally, staff considering their understanding of older people and PCC itself.

It is important that nurses have an awareness of their own attitudes regarding older people. The media often portrays older people as being dependant on others and it is inevitable that this will have an unconscious effect on our attitude (Koskinen et al., 2014) and affect our interpersonal skills that are fundamental to effective PCC. In not acknowledging the diversity of the older population, in terms of their ability and capacity, we are reducing them to a homogeneous group incapable of being asked about or making decisions of their own, for themselves (Phelan, 2011). By becoming aware of culturally influenced attitudes about the older person and how these outlooks are mirrored in the ways older people are observed, treated and cared for in society, the nurse and the MDT can better understand the premise from which to provide high-quality PCC.

McCormack and McCance (2010) developed a ‘Person-Centred Nursing Framework’ and this framework has four constructs that are fundamental to delivering PCC in the older person effectively. They are:

These constructs are presented in Figure 1.1 with examples of the questions the nurse might consider when delivering PCC in the older person.

Having taken into consideration the constructs above as fundamental to delivering effective PCC, the nurse, due to cultural differences, also needs to appreciate those intrinsic factors that will affect what can be called the ‘intergenerational conversation’ that occurs between the patient and nurse.

Bochner (2013) asserted that intersubjective values such as power, hierarchy, status, subordination and perceptions of equality affect intergenerational conversation more than previously imagined. Bochner emphasises that any contact between professional and patient can affect the communication and behaviour of both parties due to the interaction being a heavily differing value-oriented encounter. Intergenerational communication does not just include the entire range of communication skills across boundaries of age groups but also takes into account gender and cultural factors.

An awareness of these factors is important if the patient is going to be comfortable to express their needs and for the nurse–patient relationship to be mutually beneficial. It is important for the nurse to be aware of the intergenerational implications of both verbal and non-verbal aspects of conversing with those who are of a different age group, and perhaps, feeling vulnerable in a care setting. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, it is essential that the nurse be aware of his or her own socialised prejudices or prejudgements that may affect their interpersonal behaviour. Both these traits affect the tone and values of conversation that follows, in which the patient comes to recognise the identity that the nurse is now giving them, be it positively or negatively (Samovar et al., 2013).

The notion of PCC is complex and multi-dimensional. For it to be successful, the MDT needs to work at sustaining a reflective and honest planned culture change, which is necessary to embed the values of PCC of older people in daily practices. Good nurse leadership and the care environment are key influencing factors on the way that person-centredness is experienced by patients, their families and the MDT. For PCC to be experienced in a consistent and continuous way by these patients, the culture of practice has to support a compassionate, humanistic and creative way of practising, that enables care teams to flourish or achieve patient satisfaction. In adopting this change in culture, ultimately, the nurse is working towards promoting those notions around self-determination and purposeful living, often taken for granted when we are young.

Consent is one of the cornerstones of good healthcare practice. It enables patients to exercise their autonomy, their choices, their free will and self-determination. Patients should no longer feel passive recipients of care, rather consumers of a health service where equity, respect and mutuality are recognised (Department of Health, 2012). The promotion of consent allows practitioners to develop therapeutic relationships with patients and service users, promoting reciprocity, equality and trust, all of which are fundamental to the core values within the National Health Service Constitution (Department of Health, 2015). Thus, all individuals receiving care, where possible, must give their permission for that care to be delivered.

Conceptually, consent can be divided into two distinct categories: informed and implied consent (Figure 2.1).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2015) and the General Medical Council (2008) clearly articulate that any decision made by patients surrounding any aspect of their care, should be informed in nature. This requires that patients are fully aware of the reasons for their treatment, any side effects that may occur and the risk of any potential harm that may be suffered as a result of this care. Having considered all of this information, the benefits, risks and burdens, patients have the right to agree to or refuse treatment. Sometimes the refusal of treatment may be seen as an unwise decision, which is detrimental to the patient’s health and against the advice of the healthcare professionals; this refusal must still be respected in the competent patient (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015).

Informed consent needs to be integrated into all aspects of nursing care delivery, not just major surgery or medical procedures. This means that everything from assisting a patient with personal hygiene needs, to the administration of medication or the delivery of nursing procedures must be fully explained to the patient, who then agrees to the provision of that care. However, studies have suggested that informed consent prior to the delivery of nursing care is ‘under-developed’, with many nurses relying on implied consent and failing to respect refusal of treatment prior to the delivery of nursing procedures (Cole, 2012).

Within the context of healthcare the Professional Regulatory Bodies (General Medical Council, 2008; Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015), statute (Mental Capacity Act 2005, Human Rights Act 1998, Criminal Justice Act 1988) and ethical practice (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015) drive the need for informed consent. Failure to obtain informed consent has multiple consequences; for patients their human rights are violated and the acceptable standard of care expected is compromised. For the practitioners involved, lack of adherence may lead to professional misconduct hearings, employment tribunal or liability in negligence (General Medical Council, 2008; Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015). Furthermore, if treatment or care is provided without the patient’s informed consent, civil or criminal proceedings may be instigated due to charges of battery (trespass to the person) or assault (where malicious criminal intent is proven).

There are many factors that may impact upon the ability to gain informed consent from a patient, particularly if they are older. There is a need to recognise and acknowledge the diversity of the older patient population in relation to information giving and consent, thus tailoring information based around patients’ individualised needs. Language, sensory impairment, literacy and cognition are all features that could influence comprehension. Nurses must take all practicable actions to facilitate understanding where possible. Therefore, providing adequate time, a quiet environment, written information in a suitable font size and the involvement of family and friends (with consent) so more people can retain the information are practical ways to facilitate this.

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA) provides clear legal parameters for practitioners to promote autonomy, with the assumption that everyone (over the age of 16) has the capacity to make decisions surrounding their care unless evidence suggests otherwise (Box 2.1).

The principles given in Box 2.1 reduce the potential for paternalism and prejudice, clearly highlighting that assumptions regarding capacity should not be made purely on the basis of age, medical condition or diagnosis. Based upon this framework, it is important to note that some patients may be able to provide informed consent and refusal regarding certain aspects of their care, such as whether they wish to receive personal care; however, they may not be deemed competent to make more complex healthcare decisions.

If an individual is assessed as lacking capacity to make a decision about their care autonomously, those making a decision on their behalf must adopt the principle of ‘best interest’, according to the Mental Capacity Act (2005). Healthcare staff should therefore make every effort to understand what the patient would have wanted were they able to autonomously make the decision themselves. This requires the holistic assessment and understanding of the unique nature of that patient, and may require discussions with family members to establish, if not documented within an advanced decision, the wants and wishes of the patient when they had capacity.

A key issue, which must be addressed, is that family members are not able to consent on behalf of their loved one, unless they have been nominated by a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). Under the Mental Capacity Act, the attorney is an individual that the patient nominates to make choices about their health, welfare and the management of property, when capacity is lost. There is an official process to be followed in adopting this role and the LPA must be registered with the Office of Public Guardian.

Safeguarding the rights of those who have lost capacity is inherent within the Mental Capacity Act. Major decisions surrounding the deprivation of liberties, the instigation or withdrawal of serious medical treatment, long-term continuing care and rehousing will often require liaison with local authorities, Independent Mental Capacity Advocates (IMCAs) or court-appointed Deputies. The Court of Protection will hear cases surrounding serious medical treatment decisions and will try to resolve disputes surrounding differences of opinion between the patient’s carer and healthcare workers.

In order for consent to be valid, it must be made voluntarily, without coercion, and must be provided by a mentally competent patient (see Figure 2.2).

Lack of capacity may be transient or due to a long-term health breakdown such as brain injury, mental illness, levels of consciousness, phobias, confusion, delirium, intoxication and intellectual disability.

In order to facilitate truly informed consent for the competent patient, nurses must understand the dynamics of decision-making and capacity. In reviewing the concept of competence, the transient nature of lack of capacity must be acknowledged and the notion of best interest fully understood. With this comes the need to develop and enhance effective communication, individualised holistic care and the discouragement of discrimination, deceit and coercion, enabling patients to be true partners in their care.