“In The ELL Teacher's Toolbox, readers will find powerful, research‐based instructional methods and practical classroom ideas that are tried and true. This is a must‐have resource for all teachers!”

—Valentina Gonzalez, Professional Development Specialist for ELLs, Katy Independent School District, Texas

“This collection of immediately usable strategies is a godsend for teachers of English Language Learners, which should be no surprise to fans of Ferlazzo and Sypnieski. This is a book you'll want to put on the desk of all the ELL teachers you know.”

—Shanna Peeples, 2015 National Teacher of the Year

“A grab‐and‐go book of strategies for teachers of English learners. With this book, all educators can be both teachers of content and language at the same time. The ELL Teacher's Toolbox turns principles into practices.”

—Tan Huynh, teacher, consultant, blogger at EmpoweringELLs.com

“This book combines clear strategies by teachers for teachers in real classrooms. It includes a research base, points out connections to standards, and has tips on what to watch out for. A genuine all‐in‐one approach that's a winning formula for the classroom!”

—Giselle Lundy‐Ponce, American Federation of Teachers

The ELL Teacher's Toolbox is just that. A box full of tools that you will want to have at your fingertips all year long. If you teach any English learners, you'll be grateful to have this practical guide and all the reproducible resources packed into it!

—Carol Salva, Seidlitz Education, author, Boosting Achievement: Reaching Students with Interrupted Or Minimal Education

Copyright © 2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Brand

One Montgomery Street, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94104‐4594—www.josseybass.com

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 646‐8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e‐books or in print‐on‐demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data:

Names: Ferlazzo, Larry, author. | HullSypnieski, Katie, 1974- author.

Title: The ELL teacher's toolbox : hundreds of practical ideas to support your students / by Larry Ferlazzo, Katie Hull Sypnieski.

Description: Hoboken, New Jersey : John Wiley & Sons, 2018. | Includes index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017057348 (print) | LCCN 2017061783 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119364986 (pdf) | ISBN 9781119364955 (epub) | ISBN 9781119364962 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: English language—Study and teaching—Foreign speakers—Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Classification: LCC PE1128.A2 (ebook) | LCC PE1128.A2 F44 2018 (print) | DDC 428.0071—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017057348

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: ©ThomasVogel/iStockphoto

FIRST EDITION

Larry Ferlazzo has taught English, social studies, and International Baccalaureate Theory of Knowledge classes to English language learners and mainstream students at Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, California, for 14 years. He has written eight previous books, Navigating the Common Core with English Language Learners (with coauthor Katie Hull Sypnieski); The ESL/ELL Teacher's Survival Guide (with coauthor Katie Hull Sypnieski); Building a Community of Self‐Motivated Learners: Strategies to Help Students Thrive in School and Beyond; Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching; Self‐Driven Learning: Teaching Strategies for Student Motivation; Helping Students Motivate Themselves: Practical Answers to Classroom Challenges; English Language Learners: Teaching Strategies That Work; and Building Parent Engagement in Schools (with coauthor Lorie Hammond).

He has won numerous awards, including the Leadership for a Changing World Award from the Ford Foundation, and he was the grand prize winner of the International Reading Association Award for Technology and Reading.

He writes a popular education blog at http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org/, a weekly teacher advice column for Education Week Teacher, and regular posts for the New York Times and the British Council on teaching English language learners. His articles on education also regularly appear in the Washington Post and ASCD Educational Leadership.

Larry was a community organizer for 19 years prior to becoming a public school teacher. He is married and has three children and two grandchildren.

Katie Hull Sypnieski has worked with English language learners at the secondary level for 21 years in the Sacramento City Unified School District. She currently teaches middle school English language arts and English language development at Rosa Parks K–8 School.

She is a teaching consultant with the Area 3 Writing Project at the University of California, Davis, and leads professional development for teachers of ELLs.

She is the coauthor (with Larry Ferlazzo) of The ESL/ELL Teacher's Survival Guide and Navigating the Common Core with English Language Learners. She has written articles for the Washington Post, ASCD Educational Leadership, and Edutopia.

Katie lives in Sacramento with her husband and their three children.

Larry Ferlazzo: I'd like to thank my family—Stacia, Rich, Shea, Ava, Nik, Karli, and especially, my wife, Jan—for their support. In addition, I need to express appreciation to my coauthor, Katie Hull Sypnieski, who has been a friend and colleague for 14 years. I would also like to thank the staff and faculty members at Luther Burbank High School, including former principal Ted Appel, present principal Jim Peterson, and teacher‐leader Pam Buric, for their assistance over the years. And, probably most important, I'd like to thank the many students who have made me a better teacher—and a better person. Thank you, also, to David Powell, who has done an extraordinary job making manuscripts presentable for all of my books, including this one.

Finally, I must offer a big thank you to Kate Gagnon at Jossey‐Bass for her patience and guidance in preparing this book.

Katie Hull Sypnieski: I would like to thank all of my family members—especially David, Drew, Ryan, and Rachel—for their love and support. Thank you to my coauthor, Larry Ferlazzo, whom I'm proud to call my colleague and my friend. Thank you to my teaching partner, Dana Dusbiber, for her constant support and inspiration. I would also like to thank the amazing staff members and administrative team at Rosa Parks K–8 School. Thank you to the many educators at The California Writing Project who have taught me so much over the years. I must also thank Kate Gagnon at Jossey‐Bass for all of the help she has provided to us. Finally, to the many students who I've had the honor of teaching—thank you for all the love, laughter, and learning you've brought into my life.

Both of us would like to thank the many educators who have let us borrow their ideas to use in our classrooms and in this book.

If you have an important point to make, don't try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time.

Winston Churchill

We are, indeed, again hitting the important point that we must look at English language learners through the lens of assets and not deficits in this, our third book.

The ESL/ELL Teacher's Survival Guide (2012), our first book, looked through this positive lens and was categorized by themes and genres. In our second book, Navigating the Common Core with English Language Learners (2016), we applied this same lens to approaching the ELL classroom and used standards to organize our recommendations.

We're now ready to hit it a third time and share instructional strategies that again build on the assets of ELLs.

What is our definition of an instructional strategy? We define it loosely as a teaching tactic, technique, or method that can be used in a class as part of multiple lessons and across content areas. We are not saying that every strategy we discuss can be used in all lessons or in all content areas. However, we are saying that each strategy can be used in a number of different classroom lessons.

The names of each of the 45 strategies we discuss, though, don't always reflect this loose definition, but the one‐ to five‐word titles are less important than the practical classroom ideas included under each one.

We can say with confidence, however, that everything in this book does fit the definition of the root word of strategy—ag, which means to “draw out or forth, move” (Strategy, n.d.). We apply these ideas to assist students to draw out the gifts and tools they already possess and to provide them with new ones so that they can move forward in their academic, social‐emotional, and professional‐economic lives.

There are hundreds of specific ideas contained within these 45 broader strategies, including scores of reproducible student handouts. They all reflect our commitment to supporting language acquisition (being able to actually use the target language in a practical way) and not just language learning (being able to complete a worksheet on a grammar concept but not being able to apply it in a conversation). In addition, these strategies recognize and build on the gifts our ELL students (and, in fact, all our students) bring to the classroom. Finally, they all promote a classroom culture of active learning and not passivity.

These are truly teacher‐tested strategies that we have used day‐in and day‐out during our combined 35 years of teaching experience. The majority of the lesson ideas we discuss have not appeared in our previous books. Others were present in them, but they are updated with improvements or revised student handouts. One percent of the book is lifted verbatim from our first two books because we felt it was just too good to leave out.

Each strategy follows a similar outline. First, we explain what it is, followed by a short analysis about why we like it. Next, we provide research supporting its use with English language learners and list the Common Core Anchor Standards that the strategy can help meet (we've also reprinted those standards as an Appendix at the end of this book). The Application section contains the meat of the strategy, where we describe different ways to apply it in class. We then talk about what could go wrong in these lessons—and, believe us, we speak from much direct experience in this part! Next, we share various ways to integrate technology. Then, we recognize the contribution of other educators to the ideas we have discussed. Last, we share the related figures (these reproducibles and a complete list of links to technology resources discussed in the book can be accessed online at our book's website, www.wiley.com/go/ellteachertools). The 45 strategies are divided into three sections. The first section's focus relates to reading and writing; the second to speaking and listening; and the third, for lack of a better term, we're calling additional key strategies that don't quite fit under either of the first two labels. We also recognize that even the first two categories are somewhat artificial labels because most classroom lessons involve all four domains.

Though this book's focus is on English language learners, we also want to make clear that we use all these strategies, or variations of them, with our English‐proficient students. Good ELL teaching is good teaching for everyone, and we hope you will read our book and implement its suggestions in that spirit!

Independent reading, also called free voluntary reading, extensive reading, leisure or pleasure reading, and silent sustained reading, is the instructional strategy of providing students with time in class on a regular basis to read books of their choice. Students are also encouraged to do the same at home. In addition, no formal responses or academic exercises are tied to this reading.

We believe the best way for our ELL students to become more motivated to read and to increase their literacy skills is to give them time to read and to let them read what they like! That being said, we don't just stand back and watch them read. We do teach reading strategies, conduct read alouds to generate interest, take our classes to the school library, organize and maintain our classroom library, conference with students during reading time, and encourage our students to read outside the classroom, among other things. All of these activities contribute to a learning community in which literacy is valued and reading interest is high.

Research shows there are many benefits of having students read self‐selected books during the school day (Ferlazzo, 2011, February 26; Miller, 2015). These benefits include enhancing students' comprehension, vocabulary, general knowledge, and empathy, as well as increasing their self‐confidence and motivation as readers. These benefits apply to English language learners who read in English and in their native languages (International Reading Association, 2014).

Encouraging students to read in their home language, as well as in English, can facilitate English language acquisition and build literacy skills in both languages (Ferlazzo, 2017, April 10). Extensive research has found that students increasing their first language (L1) abilities are able to transfer phonological and comprehension skills as well as background knowledge to second language (L2) acquisition (Genessee, n.d.).

According to the Common Core ELA Standards, “students must read widely and deeply from among a broad range of high‐quality, increasingly challenging literary and informational texts” in order to progress toward career and college readiness (Common Core State Standards Initiative, n.d.b). The lead authors of the Common Core advocate for daily student independent reading of self‐selected texts and specifically state that students should have access to materials that “aim to increase regular independent reading of texts that appeal to students' interests while developing their knowledge base and joy in reading” (Coleman & Pimentel, 2012, p. 4).

Our students are allowed to choose whatever reading material they are currently interested in and are given time to read every day (depending on the day's schedule they spend anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes per day). Our students' use of digital reading materials in the classroom has dramatically increased in the past few years, and we discuss this in the Technology Connections section.

In order for this time to be effective—for our ELL students to experience the various benefits of independent reading discussed in the research section—we scaffold the independent reading process in several ways.

At the beginning of the year, we familiarize our students with the way our classroom libraries are organized—ours are leveled (beginner, intermediate, advanced) and categorized (fiction, nonfiction, bilingual). We organize our books in this way so that students don't have to waste time looking through many books that are obviously not accessible to them. For example, a newcomer having to thumb through 10 intermediate or advanced books before he or she finds a readable one can easily lead to a feeling of frustration, not anticipation. Students, however, are free to choose a book from any section of the library, even if that means selecting a book at a higher reading level than we would select for them. That being said, we do our best to help students find books they are interested in that are also accessible to them.

We also teach our students how to identify whether a book is too hard, too easy, or just right by reading the first couple of pages and noticing if most of the words seem unfamiliar (too hard right now), if they know the majority of the words (too easy), or if some of the words are familiar and some are new (just right). We also emphasize to students the importance of challenging themselves to improve (using a sports analogy works well—if you want to get better at basketball, you don't just work on the same shot every day) by sometimes practicing a little out of their comfort zones. We do allow students to use their phones or classroom dictionaries to look up words, but we also explain that having to look up every word usually indicates a book is too hard for now.

If you are facing a situation‐like we have at times‐when your new ELL student knows no English, doesn't have a cell phone, you don't have a peer tutor to help him or her read, there's no computer available in the classroom, and no bilingual book using that student's home language, then we make sure to get a bilingual dictionary (ideally, with pictures) that students can read. These can easily be found online for most languages, though they can be expensive. It's not ideal, but it's something.

We use independent reading time to check in with individual students about their engagement, comprehension, and future reading interests. These are not formal assessments but are brief, natural conversations about reading (“Why did you choose this book? What is your favorite part so far? Which part is most confusing? How are you feeling about reading in English?”). We may also use the time to help students find new books, listen to students practice reading aloud, talk about new words they are learning, discuss which reading strategies they are using (see Strategy 10: Reading Comprehension), and glean information about their reading interests, strengths, and challenges.

Sometimes we may ask students to respond to their daily reading in a quickwrite, a drawing, or talking with a partner. Other times we ask students to respond to their reading in their writer's notebooks (see Strategy 18: Writer's Notebook for a more detailed explanation of how we use them for reader response). We may also have students participate in one of the activities described in Strategy 2: Literary Conversations, such as creating a book trailer, conducting a book interview, or identifying and writing about a golden line.

We have our students keep track of the books they have read in English and in their home language, not as an accountability measure but as a celebration of their growth as readers. When they finish a book of any length, we give them a colored sticky note and they write their name, the title of the book, the number of pages, and a four‐ to five‐word rating, or blurb (e.g., “sad, but good ending” or “best graphic novel I've read!”). Students then stick their notes on the finished books wall (made of a large piece of colored paper).

We also have students keep a list of finished books in their writer's notebooks (see Strategy 18). We remind our students that it's not a race for who can finish the most books, but that the most important goal is that each student is making his or her own progress.

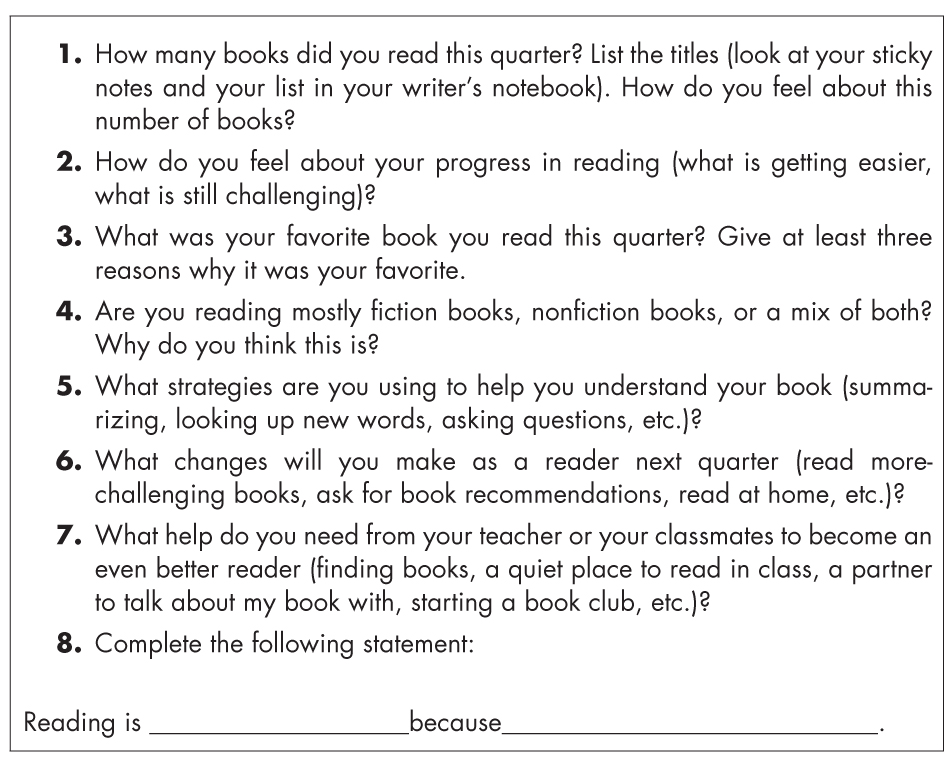

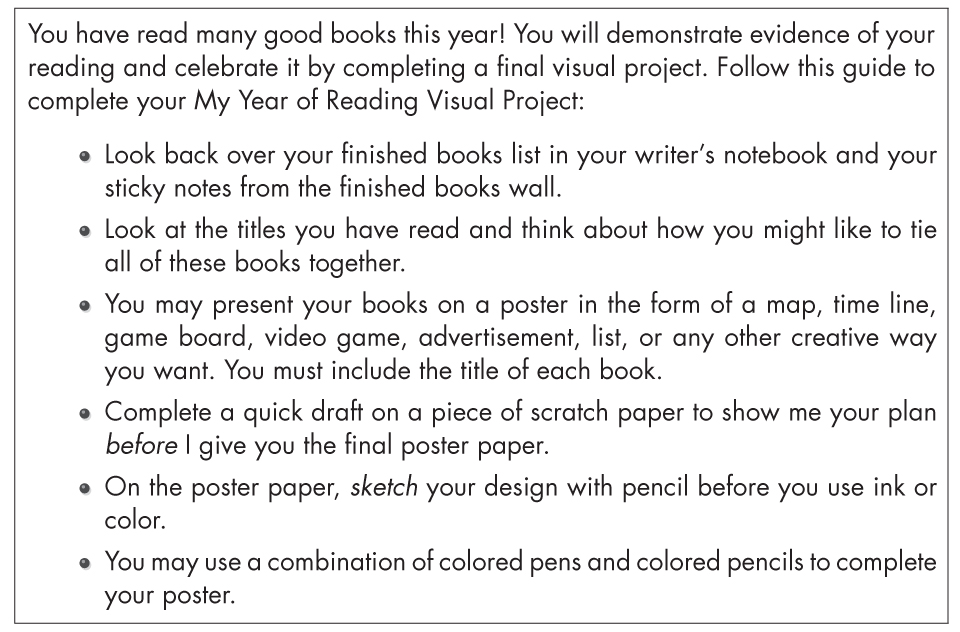

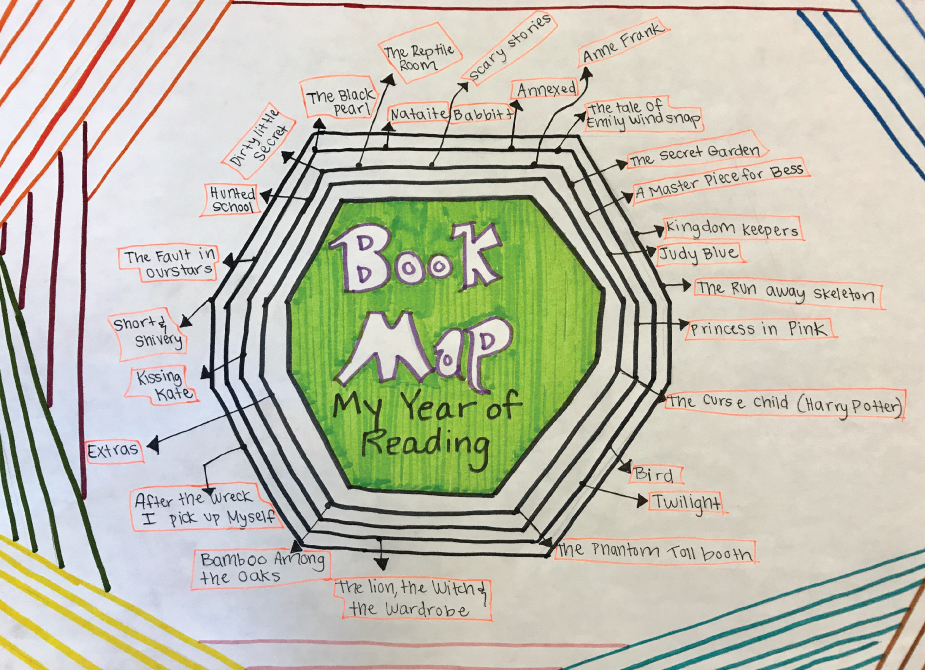

At the end of each quarter, we ask students to reflect on their independent reading (see Figure 1.1: End‐of‐Quarter Reading Reflection). At the end of the year, we celebrate all the reading our students have done with a visual project called My Year of Reading. Students use their sticky notes and lists of finished books in their notebooks to create a list of all the books they've read. Then they design a visual representation of their reading journey (a chart, a time line, a map, a bookshelf, etc.). See Figure 1.2: My Year of Reading Visual Project for the directions and Figure 1.3: My Year of Reading Student Example.

Figure 1.1 End‐of‐Quarter Reading Reflection

Figure 1.2 My Year of Reading Visual Project

Figure 1.3 My Year of Reading Student Example

Independent reading can be especially challenging with English language learners who are preliterate, not literate, or who have low literacy skills in their home language. However, new research (which we share with our students and their families) shows that learning to read creates deeper, stronger, and faster connections in the brain, even for those who are late to reading (Sparks, 2017). We frequently do lessons with all our students about how learning new things changes and strengthens the brain (Ferlazzo, 2011, November 26).

In our experience, one of the best ways to engage students facing these challenges and to build their literacy skills is through online reading activities. The online sites we have found most useful are interactive and contain leveled texts, bilingual stories, visualizations, and audio support in which words are pronounced aloud in English and in the student's home language. Many of our students especially enjoy sites that incorporate music lyrics and videos. For teachers who have limited technology in the classroom, another option is to access printable books online at sites such as Learning A‐Z or edHelper. See the Technology Connections for a list of the sites we have found most useful. In addition, explore Strategy 35: Supporting ELL Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE) for other ideas.

Providing ELL students with access to high‐interest books at their English proficiency levels can be challenging. Children's books, although often well written and available in multiple languages, are not always of high interest to adolescent learners. We've found that purchasing popular young adult fiction in English and in various home languages works especially well for our intermediate students. They can read the English version and use their home language copy as a reference—to check their understanding or to identify similarities and differences. As we stated previously, digital texts are another engaging option for adolescent ELLs and provide many features that support literacy development—glossaries, animations, audio tools, and so on (see Technology Connections for resources on digital reading).

Independent reading is a very important component of English language instruction; however, it is not a substitute for explicit reading instruction (see Strategy 10: Reading Comprehension). Ideally, it is a time when students can apply the reading skills and strategies they are learning in class to the texts they are reading independently. The teacher plays a big role in helping students reach this goal by consistently providing guidance and encouragement. It can quickly become an ineffective practice if students are not supported as they select books, read them, and interact with them. Teachers can fall into the trap of using student independent reading time to plan or catch up on paperwork. We certainly have done this and still do it now at times, but we try to resist the urge and we hope you do, too.

There are numerous online sites that provide free, high‐interest reading materials for all levels of ELLs. Links to these sites can be found here:

Portions of this section are adapted from our books, The ESL/ELL Teacher's Survival Guide (Ferlazzo & Sypnieski, 2012, p. 125–127) and Navigating the Common Core with English Language Learners (Ferlazzo & Sypnieski, 2016, p. 95–97).