The patients named here were identified in the news media at the time, together with their progress. Those who were not identified publicly are referred to only by first names, which have been changed, as have their physical characteristics. Names and physical characteristics have also been changed by others who are identified only by their first names.

To my daughters,

Alexandra and Victoria.

“I warn you to travel in the middle course, Icarus, if too low the waves may weigh down your wings, if you fly too high the fires will scorch your wings. Stay between both.”

—Ovid

Close to the Sun

Copyright © 2019 by Stuart Jamieson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used

or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or

mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information, please contact RosettaBooks at

marketing@rosettabooks.com, or by mail at

125 Park Ave., 25th Floor, New York, NY 10017

First edition published 2019 by RosettaBooks

Interior photographs come from the personal archive of the author.

Cover design by Mimi Bark

Interior design by Alexia Garaventa

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950744

ISBN-13 (print): 978-1-9481-2232-0

www.RosettaBooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Foreword

Part One: Africa

Chapter One: Starting Over

Chapter Two: Bulawayo

Chapter Three: Whitestone

Chapter Four: Serondella

Chapter Five: In This Way You Become Immortal

Chapter Six: An Unspoiled Land

Part Two: The Cutting Edge

Chapter Seven: London

Chapter Eight: Another World

Chapter Nine: In the Bush Beneath the Moon

Chapter Ten: Tiger Country

Chapter Eleven: The Difficulty of Not Self

Chapter Twelve: A Matter of Life and Death

Chapter Thirteen: Mr. Lennox Would Like to Know What the Problem Is

Chapter Fourteen: The Beating Heart

Part Three: America

Chapter Fifteen: Nobody Threw Instruments on the Floor

Chapter Sixteen: Blood and Air

Chapter Seventeen: Winning Hearts and Minds

Chapter Eighteen: On My Own in a Cold Place

Chapter Nineteen: Exile

Chapter Twenty: California Calls

Chapter Twenty-One: The Long View

Postscript

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Foreword

One of the most significant scientific advances of the past century is the ability to perform surgery on the human heart. Cardiac surgery ranks in importance with space travel, computers, antibiotics, control of communicable diseases, and other major breakthroughs made during the twentieth century.

In his memoir, Dr. Stuart Jamieson presents a vivid account of his experiences as a member of the so-called second generation of cardiothoracic surgical pioneers. In a highly engaging and readable manner, he describes the background and formative influences that led him to choose a surgical career. Like many other creative individuals, he had a fascinating early life that did not necessarily prepare him for his later professional accomplishments. Of particular interest are the stories he tells about the adventures he experienced during his developmental years in southern Africa.

Dr. Jamieson’s surgical career was marked by a new, aggressive approach to the treatment of cardiopulmonary disease. Because of his interest in heart and lung transplantation, he helped introduce many technical modifications in these procedures. He also helped pioneer strategies for overcoming tissue rejection, which had previously impeded favorable long-term outcomes. One of the most important breakthroughs to which he contributed was the early use of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporin, which substantially improved the results of transplant procedures. Perhaps the most significant of his many accomplishments, however, is the operative procedure he devised to solve the difficult problem of pulmonary embolism. That operation is among the most challenging and complex of all cardiopulmonary procedures. His results with it are unequaled.

This book includes intimate insights into the lives of pioneers in heart surgery and transplantation, weaving the history of heart and lung surgery into Dr. Jamieson’s own history. With its generous illustrations and human interest stories about both patients and physicians, Close to the Sun should appeal to medical professionals and the general public alike. Complex medical situations have been made easily understandable to laypersons.

On a personal note, I recall being asked many years ago by the British Heart Association to give an invited lecture at the Brompton Hospital. Arriving at Heathrow Airport, I was met by a bright young surgeon who introduced himself as Stuart Jamieson. He was then a registrar at the Brompton Hospital and had been assigned to escort me during my visit. We enjoyed the first of many enjoyable conversations. I was impressed by him at the time, and that excellent impression has continued over the years. I am proud of our friendship.

Denton A. Cooley, MD

Founder and president emeritus

Texas Heart Institute

Houston, Texas

PART ONE

AFRICA

CHAPTER ONE

STARTING OVER

The plane from Cape Town was crowded. Most of the passengers were white and appeared well-off, dressed in crisp khaki and headed home from shopping in South Africa for the essentials they could no longer find in Zimbabwe. I’d heard that in the years since the civil war had toppled white rule in the country formerly known as Rhodesia, it had become nearly impossible to buy anything that wasn’t made there. Now a trip to the store for toothpaste required international travel. We flew over dusty plains and bouldered outcroppings. As the plane traveled into Zimbabwe and made its descent, I saw that the airport at Bulawayo, which I remembered as a grand place, was little more than a crumbling airstrip in the middle of a scrubby field. We landed, pulled up to the terminal, and got off at Gate 5—an amusing conceit, as it was the only gate. Inside I noticed a few game heads on the walls, forlorn reminders of a different time.

The lines in the immigration area were long and slow. The thump of papers and passports being stamped echoed monotonously. When I at last reached the front, I handed my passport to a young black officer in a starched uniform. He looked at it for a long moment and then up at me.

“You were born here, in Bulawayo?” he asked.

“Yes,” I answered.

“Welcome back, sir,” he said, stamping my passport and waving the next in line forward.

I rented a car and drove through town, which took only a few minutes. After thirty years, everything looked familiar but in disrepair. The streets were crowded with people. AIDS had begun its hollowing out of the population, and nearly everyone I saw was either young or old. There was nobody in between, and nobody seemed to have anything to do. A little beyond the edge of town opposite the airport, I came to our old house. It looked more or less as it had, though it was now surrounded by a high wall. A steel gate guarded the entrance to the driveway. A sign of different times. As I looked the place over, two young boys tore around the property on small motorbikes. I remembered how my father often spent his weekends perched on a low stool weeding the lawn, looking smart in his bush hat and listening to the cricket matches on a transistor radio. Presently, a Mercedes swept up to the gate. An impatient-looking white woman honked the horn, and a gardener ran over to let her in before going back to his watering.

I headed for Whitestone, the boarding school I had gone off to as a young boy. The dirt road was now tarred, and houses stood in rows on either side where the bush had once crowded in. There were children in the schoolyard, both black and white. This I’d expected, though the fact that half were girls brought me up short. Whitestone had been a boys’ school in the grim English tradition when I’d attended, run by incompetent instructors whose ignorance and cruelty were thought to be the best sort of influence on the leaders of the future. This had been a torture then reserved for whites only. I’d hated every minute of it. The students no longer wore khaki but were now smartly turned out in crimson jackets with a bird embroidered on the front pocket. The school itself appeared little changed. I ruefully contemplated the motto over the door: Veritas Omnia Vincit. Truth conquers all. It’s a concept that’s easy to believe until you’ve lived long enough to see through it.

Farther out of town, I stopped in at Falcon College, where I attended high school, “college” being an English term for secondary school. Falcon was located on the site of an abandoned gold mine, whose plain stone buildings had been converted to classrooms and dormitories. I remembered the swelter of classes beneath those corrugated iron roofs as the African sun burned its way across the day. Now there was air-conditioning. And just as at Whitestone, the school was fully integrated. Students went about campus in mixed groups, seemingly oblivious to race. They proved a point I would not make out until years later, when a classmate wrote about it in the Falcon newsletter. Falcon had become a color-blind oasis in the heart of Africa, a living model for what some had once hoped all of Rhodesia could become. That was not to be.

My father was a doctor. He had sided with the liberals in Rhodesia. They favored an orderly transition away from white minority rule. The exclusion of blacks from the colonial government was wrong, he believed, and would end either well or badly. White rule did end, though not while my father was alive to see it, and not in the way he hoped it would. Rhodesia became Zimbabwe in a cataclysm of bloodshed and terror. Its black citizens, most of them uneducated and possessing no knowledge of the outside world, were ill prepared for liberal, Western-style democracy. The concept of “one man, one vote” is fair enough. But when the average person cannot read or write, does not know that the oceans and continents exist, has no idea even that there are other countries, other people—then the idea of self-rule falls down, because a vote is going to be for sale. And they were. Zimbabwe is a country now run by a corrupt, authoritarian black government that exploits its citizens more brutally than the white government ever did. That is Zimbabwe’s history and its torment.

I’d come back to Africa to see all this for myself, but also because I’d recently experienced a calamity of my own. I’m a heart surgeon. My career had taken off in the pioneering days of heart transplantation, a life-saving operation that I’d helped make routine. At a young age, I’d been given my own cardiac center at a major university in America and turned it into the world’s busiest heart-transplant hospital. And then, abruptly and unjustly, I was forced out, my reputation in tatters. I’d been a success in every way except at perceiving the envy that gnawed at the people I worked with. I loved what I was doing and assumed that everyone around me did, too. I was wrong.

One of my favorite stories when I was growing up was the Greek myth of Daedalus and his son, Icarus, who escaped their confinement on the island of Crete by flying away on wings Daedalus fashioned from branches of willow bound with wax. Daedalus, fearful of the hazards of the journey and seeing his son’s rapture at the prospect of flight, warned Icarus to fly safely above the sea, but not so near the sun as to melt his wings. Icarus ignored this advice to stay on the middle course, instead soaring high into the sky. And when his wings melted, he fell into the sea and was lost.

The lesson of Icarus is that excessive pride or self-confidence can be fatal, though I never saw it exactly that way. To me Icarus was not foolish, but bold. Wanting to do something great isn’t hubris, to my way of thinking, but neither is it entirely safe. Extraordinary achievement does not lie along the middle course. Heart surgery is not for the timid, and in the beginning every breakthrough carried immense risk. Doctors and their patients flew not just close to the sun but directly at it. For me it was intoxicating. True enough, when I did fall, it was a long way down. I’d lost almost everything. But soon I’d be ready to go up again. My visit to Africa was a prelude to starting over.

I have always enjoyed heights, the thrill of pioneering achievement, despite the risks.

CHAPTER TWO

BULAWAYO

My story begins in a place and in a way of life that no longer exist. In a sense, I am homeless, cut off from the world I knew growing up in the heat and dust and stark beauty of southern Africa. And yet that Africa lives in my memory. Since I have left, I have traveled to all parts of the world and operated on paupers, presidents, and princes. But in the cold still of the dawn, wherever I am, my mind falls quickly back to those early mornings on the Zambezi River. In whatever country in the world I find myself, a part of me is still there.

I reminisce over the early cool dawns on the river. The mist lay still on the water and crept along the riverbank. Cape buffalo browsed in the bush, hulking black shadows that moved noiselessly among the trees, pausing now and then to stare balefully in my direction as they chewed. They breathed clouds of steam in the morning light. There was a peace then that I never since have achieved.

I remember, too, our summer home, a cottage called Serondella, on the Chobe River, a tributary of the Zambezi. I learned to water ski on the Chobe, a perilous enterprise on account of the crocodiles and hippos with which we shared the river. And I remember our home, Raigmore, in the town of Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia, where I was born in 1947. My parents named the house for the place in Scotland where they met during the war. It was a sprawling one-story home, painted white, with many windows and an encircling veranda that looked out over several acres that were ours. The windows had bars on them for security—everyone’s did—though I don’t remember ever feeling this was necessary. The house had no air-conditioning and a fireplace that was unneeded except for a few weeks in the cooler months. There was a guesthouse in the back, and behind that were the servants’ quarters. My father had a large study that was lined with books and maps on which he marked the routes of many of Africa’s pioneering explorers. In the evenings after dinner, he would sit in his study alone with his pipe and read about the history of Southern and Central Africa. He seemed to know everything about the part of Africa that we called home.

My mother delivered me at the Lady Rodwell Hospital, which stands to this day, sun splashed in crisp, colonial whitewash with a red slate roof, though I doubt that it is still strictly a maternity hospital, and certainly it is no longer exclusively for whites. Surrounded by palm trees and a neatly kept lawn, Lady Rodwell was adjacent to Bulawayo General Hospital, one of the hospitals at which my father worked and where he later died. There was no hospital then for blacks.

We moved to Raigmore, in a suburb of Bulawayo called Hillside, when I was still a young child. I had an older brother, Chris, who’d been born in England, and eventually a younger sister named Margy. My earliest memories are of the gardens at Raigmore. The large lawns were lush during the rainy season from November to February, the Rhodesian summer. The rain came in thunderstorms, torrents that lasted a few hours, after which the sun reappeared and the air was clear and fresh. Jacaranda trees lined the flower gardens, which contained flame lilies, orchids, and hibiscus. In the winter months, the rain ceased. Sometimes the grass withered from lack of watering, but it always recovered when the rainy season returned.

My favorite tree was a marula in the lower garden in the front of the house. Although there were no elephants in Bulawayo—the only wild animals routinely encountered there were snakes—everyone in that part of Africa knew that elephants love to eat the fruit of the marula tree. In late summer, when the fruit has fallen to the ground and turned a soft yellow, elephants have been known to eat so much that the fruit ferments in their stomachs and they get drunk. Elephants can be dangerous, and tend to be more so when inebriated, but it is a great sight to see an elephant barely able to stand, or see one careening drunkenly through a grove of trees, shearing off branches as it goes. Many years have gone by since I enjoyed a marula, but the bittersweet taste is still fresh on my tongue.

Like many of the white families in Bulawayo, we had a swimming pool. There was also a tennis court. It was seldom used but was an object of fascination for me, as it required the constant attention of our gardeners. The court had an earthen surface, not clay, but dirt from giant anthills that was saturated with used engine oil and then pressed flat with a huge roller made of steel and concrete. It took two gardeners to pull it, and it was a mystery as to how the unwieldy contraption had come to be kept within the walls and wire netting surrounding the court. The only answer had to be that it was there first. Despite the continuous labor invested in maintaining the court, in truth its greasy, uneven surface was never satisfactory for the tennis. We weren’t much interested in playing, anyway, in the heat and sun, and eventually it was paved over.

I did use the tennis court for another purpose, however. I learned to shoot on it. There was a solid stone wall at one end that was an ideal backstop for target practice with a pellet gun my father bought for us. I must have been six or seven. I discovered that I had a talent for shooting. I could hit anything with that gun, even dragonflies as they flew around the swimming pool. Being a good shot was important in Africa. One day it would save my life.

Bulawayo sits on a plain, in the southwestern quadrant of what was then Southern Rhodesia, between the equator to the north and the Tropic of Capricorn to the south. It is some four thousand feet above sea level, with a moderate climate that is never cold and rarely sweltering. It is a young city, a town, really, that was barely fifty years old when I was born. Its history before then was bloody, and began when it was first colonized not by white Europeans, but by an invading force of black Africans coming north out of South Africa, which was then known as the Cape Colony.

These were Zulu people, led by a great field general named Mzilikazi. Mzilikazi had been a military leader under the legendary king Shaka Zulu. But after a rift with the king in 1823, Mzilikazi led a contingent loyal to him north, across the Limpopo River, into what would later become Southern Rhodesia, and then Rhodesia, and in the current chapter of this history, the country we now call Zimbabwe. Mzilikazi and his band wandered for a number of years, conquering local clans wherever they were encountered, killing freely and burning villages to the ground. Once, when Mzilikazi got separated from his forces and was presumed dead, one of his sons took charge. When Mzilikazi unexpectedly returned, he immediately executed the son and all who had supported him.

Eventually Mzilikazi settled his people in a rugged region called the Matopos Hills, where they became known as the Matabele, and the area under their control Matabeleland. The Matabele remained warlike, measuring their wealth in the livestock they owned and the number of enemies they had killed. The displaced tribe, a group called the AmaShona, fled to the north. The conflict between these two groups continues to this day; Robert Mugabe, the longtime president of Zimbabwe and a member of the Shona tribe, is responsible for many atrocities against the Matabele.

Mzilikazi died in 1869. Kuruman, the son of his senior wife, disappeared mysteriously. Lobengula, another son by a lesser wife—Mzilikazi had two hundred wives—seized control, killing those who opposed him. It was to be a brutal reign, maintained through regular executions of anyone suspected of disloyalty. Sometimes the charge was witchcraft, though no excuse was needed. Lobengula settled himself in a cluster of huts surrounded by a stockade—a kraal—to the north of the Matopos Hills that came to be known as Gu-Bulawayo, “The Place of Slaughter.” This would one day become my home.

Toward the end of the 1800s, white ivory hunters crossed over the Limpopo River and into Lobengula’s land. They included the famous explorer and elephant hunter Frederick Courteney Selous. In 1888, a contingent representing Cecil Rhodes, the soon-to-be prime minister of the Cape Colony and head of the British South Africa Company, arrived at Lobengula’s kraal looking to negotiate a monopoly on gold and other mineral deposits. The talks stalled, as other white adventurers—Dutch Boers and the Portuguese—tried to convince Lobengula he was being swindled. As tensions escalated, it seemed that Lobengula might shortly resolve the impasse by simply killing every white man he could find.

At the eleventh hour, a Scottish physician named Leander Starr Jameson arrived on the scene. Jameson was named after an American tourist, Leander Starr, who had saved Jameson’s father from drowning. Because of poor health, Jameson had gone to South Africa in 1878 and started a medical practice at Kimberley, where he treated many influential people. He also became a close friend and confidant of Cecil Rhodes. Jameson traveled to Gu-Bulawayo at Rhodes’s behest and calmed the situation there by treating Lobengula for gout and an eye condition. Lobengula was so delighted that he made Jameson an inDuna—an adviser and ambassador. Jameson was the only white man to have undergone the initiation ceremonies for this honor.

Jameson concluded a deal with Lobengula granting exclusive mining rights to the British in exchange for money and guns. It was stipulated that Lobengula would remain the ruler of his land, and anyone coming into it to dig would have to acknowledge his authority. The agreement was signed on October 3, 1888—the starting date for British colonization of Matabeleland.

Lobengula soon regretted his concession to the British and threatened war against the white colonists. There was animosity on both sides. Even the elephant hunter Selous, who had been Lobengula’s friend and supporter, was disillusioned by the Matabele. On a visit to England in 1889, Selous was invited to a breakfast by the Anti-Slavery Society in honor of two Matabele envoys. Selous declined, explaining in a letter, “It does strike me as incomprehensible that your Society above all others should have chosen to so honor the envoys of a tribe such as the Matabele…a people who, year after year, send out their armies of pitiless, bloodthirsty savages and slaughter men, women and children indiscriminately—except for those just the ages to be slaves…” Selous was referring to the Matabele’s treatment of the Shona.

On September 12, 1890, a military volunteer force of settlers, organized by Cecil Rhodes and guided by Selous, founded Fort Salisbury, named after Lord Salisbury, the British prime minister at the time. Located about 250 miles northeast of Bulawayo, Fort Salisbury subsequently became known simply as Salisbury, the colonial capital. It is now called Harare.

In 1893, Leander Starr Jameson, by then the administrator for Rhodes’s British South Africa Company, ordered the Matabele’s armed regiments out of the area of Gu-Bulawayo. This was a direct challenge to Lobengula, and war became inevitable. Since the whites were badly outnumbered, Jameson decided he should strike the first blow. Troops were gathered in Salisbury and in neighboring Bechuanaland, now Botswana. A third column was raised at Fort Victoria, under the command of an officer named Allan Wilson.

The three forces met at Gu-Bulawayo, but Lobengula had vanished. Dr. Jameson ordered a pursuit, and on December 3, 1893, colonial soldiers reached the banks of the Shangani River, 120 miles north of Gu-Bulawayo, at sunset. Captain Wilson took twelve men to reconnoiter the far bank, intending to return before dark. But when Wilson discovered Lobengula’s camp, a gathering of seven thousand armed Matabele, he sent back a message saying that he would remain on the far side of the river for the night and attack at first light to capture Lobengula. Twenty men were sent across to reinforce Wilson’s scouting party.

The next morning the thirty-two-man Wilson patrol found itself surrounded by thousands of Matabele. Wilson summoned three men to cross back over the river for help. One was Frederick Burnham, an American from Minnesota, who had come to Africa looking for more adventure after fighting in the Indian wars. He was joined by Pearl Ingram, known as Pete, another American, and William Gooding, an Australian. Burnham, an experienced scout, told Wilson that he thought reaching the other side was impossible, but that he and his two companions would try. Fighting their way through the Matabele, then swimming the flood-swollen Shangani River, they discovered the main force fighting for its life against a Matabele ambush. There would be no more reinforcements coming.

The Wilson patrol ringed their horses around themselves and shot them to provide a protective barricade. A fierce battle was waged until their ammunition ran out. Every man was wounded. Wilson was among the last to die. Later, the Matabele warriors told the story of Wilson’s valor. The badly wounded men had loaded their rifles and passed them to Wilson, who continued to fire. When the ammunition was spent, the men of the patrol who could stand rose and sang “God Save the Queen.” Wounded in both arms, Wilson, staggering and without a weapon, advanced toward the Matabele. Though one of the Matabele stabbed him, Wilson continued his approach. The warrior shouted, “This man is bewitched; he cannot be killed!” and threw away his spear. Wilson then fell forward on his face, dead. The Wilson patrol had been outnumbered by more than two hundred to one.

Allan Wilson’s “last stand” was one of the Rhodesian origin stories that I learned and revered as a boy. Though my parents had come from other places, I never thought of myself as anything but Rhodesian. To me, men like Selous and Jameson, Wilson, and Rhodes were heroes—founding fathers as noble and courageous as the founders of the United States, where I have lived for many years and of which I am now a citizen. Like this country’s founders, Rhodesia’s were men of their time, brave and far-sighted, but also perhaps imperfect and dependent on a class system based on race that was fraught with inequality and was ultimately unsustainable. The bones of Allan Wilson and his men were buried at the Matopos Hills, at a place Rhodes named World’s View. Rhodes was buried there in 1902, and later his friend Leander Starr Jameson was placed in a grave beside him. A monument to Wilson and his men stands there today, unmolested despite the current strife in the country.

Lobengula died two months after the destruction of the Wilson party, knowing that the inexorable advance of the white men could not be resisted forever. Before his death he compared himself and his kingdom to a fly that had been eaten by a chameleon: “The chameleon gets behind the fly, remains motionless for some time, then he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then another. At last, when well within reach, he darts his tongue, and the fly disappears. England is the chameleon, and I am that fly.”

Although Lobengula was gone, the Matabele army had not been defeated. In March 1896, there was open rebellion once more. With first the Matabele, then the Shona three months later, the tribes erupted in violence, slaughtering hundreds of white settlers—a shocking 10 percent of the European population. The Second Matabele War, as it is now known, is celebrated in present-day Zimbabwe as its First War of Independence.

During the Second Matabele War, the Gu-Bulawayo morphed into Bulawayo. It was besieged by the Matabele forces, and a defensive encampment was established there. The situation was grim—each evening nearly a thousand women and children slept on the ground within an inner defensive wall of wagons. Rather than wait for attack, the settlers mounted patrols, called the Bulawayo Field Force. Their leaders included Selous and also Frederick Burnham, one of the Wilson patrol’s three survivors. These quick-strike parties patrolled the countryside, rescuing settlers as they could. Although outnumbered, they soon attacked the Matabele directly. Twenty men of the Bulawayo Field Force were killed and another fifty wounded within the first week of fighting.

Relief forces arrived in late May 1896 to break the siege. An estimated fifty thousand Matabele retreated to their stronghold in the Matopos Hills south of Bulawayo. The turning point came when Burnham and a young scout named Bonar Armstrong made their way through to the Matopos Hills looking for the spiritual leader of the Matabele, Mlimo, who claimed to be invulnerable to the white man’s bullets. Burnham and Armstrong tethered their horses near the mouth of a cave where Mlimo lived, a sacred place to the Matabele. When Mlimo returned, he started his dance of invincibility with the Matabele looking on in awe from outside. Burnham shot Mlimo through the chest. He and Armstrong then fled on horseback just ahead of a thousand stunned Matabele warriors in pursuit. The two men outran their pursuers all the way back to safety at Bulawayo.

That autumn, Cecil Rhodes, accompanied by Burnham, went unarmed into the Matabele camp in the Matopos Hills and persuaded the warriors to lay down their arms, ending the Second Matabele War in October 1896. Within a year white colonists had successfully settled in much of the territory known as Southern Rhodesia. In 1953 Southern Rhodesia joined with Northern Rhodesia, across the Zambezi River to the north, and with Nyasaland, to form the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The Federation lasted ten years, until Nyasaland broke away and became Malawi and Northern Rhodesia became Zambia. Alone again, Southern Rhodesia became just Rhodesia in 1965. That same year, in an attempt to quell a rising call for integration of the government, Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith issued the Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom. This would lead to years of unrest and ultimately civil war.

Frederick Selous had been wounded during the siege of Bulawayo. Afterward, he returned to his ranch not far from Bulawayo and rebuilt his house at Essexvale, which had been burned by the Matabele, who also stole all of his cattle. The house, where Selous watched elephants from his veranda, was situated on a bend in the Lunga River, near where I went to school. My stepfather later owned this ranch. The epic saga of imperialism and conquest that was Rhodesia mingled in me with a deep love of that place and its native people. Friends today say, usually with suspicion, that I am a colonial.

But how could I not be?

And so I was born in wild Africa, in Bulawayo, less than a lifespan after the Second Matabele War. The Matopos was one of my favorite haunts. I loved to visit the cave where Frederick Burnham shot Mlimo, where I lived with ghosts past, and where the history of Rhodesia felt alive to me. The cemetery at Rhodes’s World View stood atop a granite hill. I climbed there often, to sit among the graves and the Wilson memorial, and to look out over the valleys below. We used to pick the small “resurrection plants” from between the rocks. To all appearances the plants were brittle and dead. When taken home and put in water, they turned green again.

This was my heritage, the story of my country. The places from which my family had come were abstractions to me—remote and alien. My English grandfather had emigrated to Australia in 1893, where he taught chemistry at Scotch College in Melbourne and authored several widely used science textbooks. Grandpa, a tall, elegant figure, always wore a three-piece suit with a hat. He carried a walking stick or rolled-up umbrella at all times, regardless of the weather. He smoked, always using a cigarette holder, and carried his cigarettes in a silver case. I only met him once. He came to stay with us for six months during the African winter, from March until August 1952, when I was five. I remember him as mysterious and aloof.

My father, George Arthur Jamieson, was born on Palm Sunday, March 23, 1902, in Gawler, South Australia. I don’t know much about his early life, though it was apparently colorful. He became a doctor, earned enough to invest in racing horses and gold mines, and was on one occasion thrown out of Raffles, the famous Singapore hotel, for being drunk and disorderly. Later in life he was reserved. I don’t think I ever heard him raise his voice. He was thin, just over six feet tall, and had a mustache. He wore a suit and waistcoat most of the time, and smoked Old Navy cigarettes. Strangely, he sounded English. Apparently his father would not permit him to speak in an Australian accent.

My grandfather and grandmother in 1908. My father is on the left.

During the Second World War, by then a middle-aged bachelor, he went to Britain and joined the Royal Air Force, rising to the rank of wing commander. His primary duties were medical, but he also flew missions over France. Posted in Scotland, he became aware of a young woman who worked on the base as a plotter in the fighter operations room, moving small placards around on a map with a long stick to track the locations of planes aloft. Janet Winifred Pascall was eighteen, twenty years younger than my father. She was almost six feet tall, pretty and sure of herself. And she was used to the attentions of the men on the base. One day my father came up to her and announced that he owned a yacht and planned to go sailing later that day. If she cared to join him, he said, she should be at the dock at three in the afternoon. She was.

They married in 1945.

My parents told me little about the war, but my mother once mentioned the distress she experienced at hearing over the radio the screams of pilots shot down in their burning planes. She had been drinking and laughing with many of them the previous night in the pub. After the end of the war, my father’s adventurous nature took over. They moved to Southern Rhodesia, where he set up practice as an ophthalmologist and ear, nose, and throat doctor. My mother and my brother, who was then a small baby, came out in late 1946 on a troop ship under appalling conditions. When she arrived at the docks in Cape Town, all of their luggage had been lost. They were delayed a few days before embarking on the three-day train trip through southern Africa to Bulawayo. My mother received a warm welcome from my father at the train station in Bulawayo. I was born eight months and two weeks later.

My mother’s parents eventually came to live with us at Raigmore. I remember their first visit when I must have been a few years old. They flew out from London in a civilized fashion, before jet aircraft were in commercial use. They came in a flying boat that landed on a series of large rivers as it progressed southward. They would anchor at nightfall and dine and sleep on the plane. I suppose they must have landed on the Nile, and the Congo, and the great lakes of Africa. Their final water landing was on the Zambezi River above the Victoria Falls at Livingstone. They then took another airplane to Bulawayo.

For several weeks my parents had been telling me that I was finally to meet Granny and Grandpa. I was excited, even though I was not sure who Granny and Grandpa were. Since there was no municipal airport at Bulawayo, commercial planes landed at the military airbase, where my father, who had served in the RAF reserve, was always welcome. After I met my grandparents at the airport, I continued to ask, “Yes, but where are Granny and Grandpa?” The concept of extended family was new to me, because we lived so far away. During this trip, my mother’s parents decided to move to Africa to live with us.

I am not sure my father was entirely happy about this, but he built them a house seventy-five yards from ours. My grandfather became my great friend and confidant. When I was confined to bed for three months with brucellosis at about the age of ten, he used to play draughts (checkers) with me. I got to know him well during that time. Grandpa liked to play bowls at the Bulawayo bowling club. Twice a week he would come out of the cottage wearing a green striped blazer and white trousers, with special bowling shoes. He carried his bowls in a little case, inscribed “WWP.” These were his initials, Walter Wilfred Pascall, but he said it stood for “World’s Worst Player.” That couldn’t have been true, because he represented Southern Rhodesia in the Empire Games in Australia.

Life at Raigmore had a comfortable colonial rhythm and formality that I found agreeable. Our parents did not coddle us in any way. On the contrary, they were physically remote from us, loving but not demonstrative about it. The children were to be seen and not heard, and were certainly not allowed to be an inconvenience. We dressed for dinner every evening without exception, my father in black tie and Chris and I in jackets and ties. The meal was attended by our houseboy, Simon, who was of course black and I thought handsome in his starched white uniform and red fez. We had a nanny, Emily, a soft, round Matabele woman, who wore a blue dress with a starched white apron and white cap. I loved the smell of her skin, always scented with the Palmolive soap she used. She had trouble pronouncing Palmolive and called the soap “Plumleaf insopi,” insopi being Zulu for soap, a European invention. When we sat outside on the sunny afternoons, I would trace patterns and do drawings on her skin with a twig. I loved Emily and spent a lot more time with her than my parents. We would sing the English nursery rhyme “Who Killed Cock Robin” in Zulu. I spoke Zulu better than I spoke English until I went off to boarding school. Emily was part of the family and lived in a house at the back of the garden.

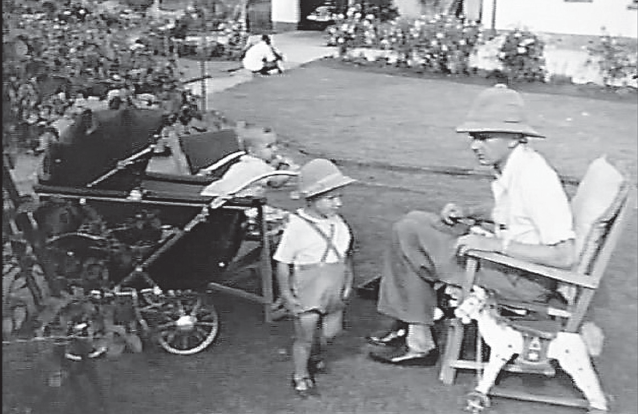

At Raigmore with my father and brother, 1948.

We had other servants at home besides Emily and Simon. We had a cook and several “garden boys,” who looked after the grounds, wearing khaki shirts untucked over their khaki shorts. Barefoot, unlike the house servants, they were usually seen with a wheelbarrow or garden hose. It was a happy household, one that to my young mind comported perfectly with the world and everyone’s station in it.

Raigmore. From left to right: My sister Margy, Simon (in his white uniform and fez), me, Emily, my brother Chris, and my mother.

Bulawayo was still a dusty provincial town with broad streets designed by Cecil Rhodes to allow a wagon behind a full span of sixteen oxen to do a U-turn. The streets were so wide that cars could park nose-in on either side, and then in two rows nose to nose down the middle, still leaving two lanes of traffic going each way. There were only three traffic signals in town. Bulawayo had some industry—a cement factory and a slaughterhouse. The white population was about five thousand, while there were around 250,000 blacks. Most blacks who didn’t work and stay at white homes lived in small cement houses in a part of town known as “the location.” Only whites paid taxes, and so it was a struggle to find the money for the education and infrastructure that would make black advancement possible.

Cecil Rhodes, who died three days after my father was born, was a towering figure in this isolated place. Bulawayo in most ways was still an outpost not unlike the old pioneering towns of the American West. Rhodes had made his fortune in the diamond fields of Kimberley by buying up the small diamond operations. He was financed in this by the Rothschild bank. He died at forty-eight, leaving a provision in his will for the famous Rhodes Scholarships at Oxford University. Rhodesia was named after him, a legacy now gone.

I remember a curious thing, a project my father undertook that continued for several years. We had a long, unpaved driveway that entered the property from a dirt road. There were pillars on either side of the entrance, but no gate. The drive curved up toward the house and circled back on itself. One day, my father decided to pave the driveway with bricks. These were not cobblestone pavers, but actual bricks, the sort you might build a wall with, turned on their sides and laboriously set in place in a zigzag pattern, three at time, first this way and then the other. He started at the house and worked toward the road. The driveway had to be excavated and leveled by hand to bring the bricks flush with the ground, and then meticulously prepared with sand, on top of which the bricks were carefully tapped in place.

My father did all this work by himself. Every Sunday he’d sit on a small canvas stool, setting bricks. Progress was made by the inch, season after season, and after several years we began to wonder if the work would ever be finished. And then my father abruptly halted when the brick surface was still some twenty feet short of the road. It was strange. I don’t think he wanted to finish. It was if he thought his life might be over if he did.

There was a social scene in Bulawayo, and my parents enjoyed it. They liked their friends and they liked their whiskies at the end of the day. A small difficulty was that my father also liked to invite black guests to the garden parties we held at our house from time to time. This was considered improper, and it also caused problems with our servants, who felt they should not be compelled to wait on other blacks, as this was beneath their dignity. My father would patiently explain that they worked for him and that meant taking care of any guests he decided to entertain. Simon and the others complied, but I don’t think they were happy about it.

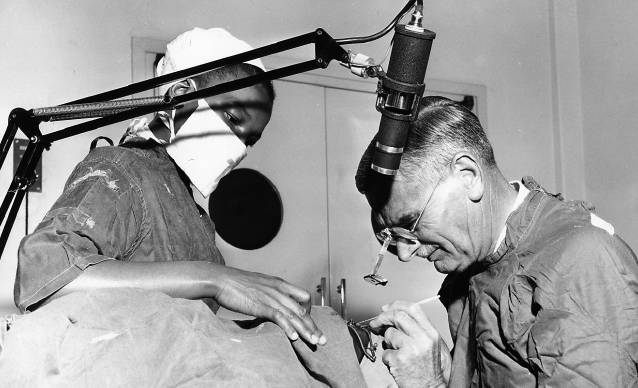

When I was about eight years old, my father was instrumental in the construction of an African hospital in Bulawayo called Mpilo, where blacks could finally receive medical attention. He usually worked there a couple of days a week. He never charged his patients at Mpilo, but I think he found it rewarding in other ways. Blacks in Africa often developed cataracts, and my father changed many lives with the surgery that corrects this problem. Mpilo is an African word for “life.” Today, Mpilo Central is the largest hospital in Bulawayo and the second largest in all of Zimbabwe, and there is a plaque in the corridor to my father’s memory.

My father operating at Mpilo Hospital.

Given the brutal history of apartheid in neighboring South Africa, it’s natural to think that the racial divide in Rhodesia was the same. But this was not the case. To be sure, there was a sharp demarcation between the races. Whites were the ruling class, and blacks were the servants. So the blacks were exploited, no question. And they were also denied self-governance. The government was white. But neither whites or blacks regarded one another with malice. There was not the kind of resentment between the races that existed in South Africa, or even in America, for that matter. Everyone was treated with respect. No one was forced to work, and certainly nobody was owned as they once were in this country. It’s hard to explain, but the racial environment felt nontoxic when I was growing up. And that undoubtedly helped to mask the underlying injustice of the situation, the unspoken but abiding tensions that would one day explode.

From my earliest memories, I knew I wanted to be a doctor. I was inspired by the dedication of my father, and by the thought of making a difference in people’s lives. And I thought that surgeons made the biggest difference. I loved the idea that a surgeon could fix people. At a young age, I would “operate” on grapes, removing the pits and sewing the skin up again with a needle and thread. But medicine was far in my future, and looming ahead was boarding school, a break with childhood from which you never returned. Being sent away to a good school was considered a privilege, an expensive one. I remember how it started.

I was left standing at the end of a long driveway in the hot afternoon sun, with a tin trunk by my side. A black beetle stirred in the sand at my feet as my parents drove away in the dust. I stared up at my new home, Whitestone School. It was only on the outskirts of Bulawayo, but it might as well have been in another country. I had left home for good. I was eight years old.