This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2013 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact sales@overlookny.com, or write us at the above address.

First published in Great Britain by Granta Books, 2013

Copyright © AspWords, 2013

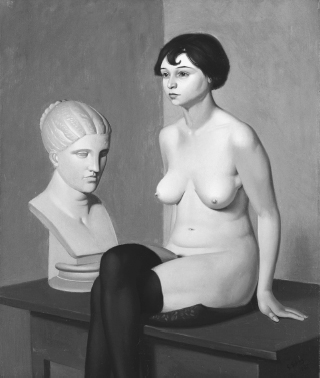

Image on pages 1, 255 and 379: Georg Scholz, Weiblicher Akt mit Gipskopf (Seated Nude with plaster Bust) 1927 © Vereinigung der Freunde der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Karlsruhe e. V. Image on pages 87 and 381: Elizabeth Taylor’s profile on DVD cover of Cleopatra © 20th Century Fox/Everett/Rex Features. Image on page 275: Bust of Lucius Munatius Plancus © The Art Archive / Musée de la Civilisation Gallo-Romaine Lyon / Gianni Dagli Orti. Image on pages 315 and 322: Jan de Bray (c.1627–97), Banquet of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, 1652. Oil on canvas. Supplied by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012.

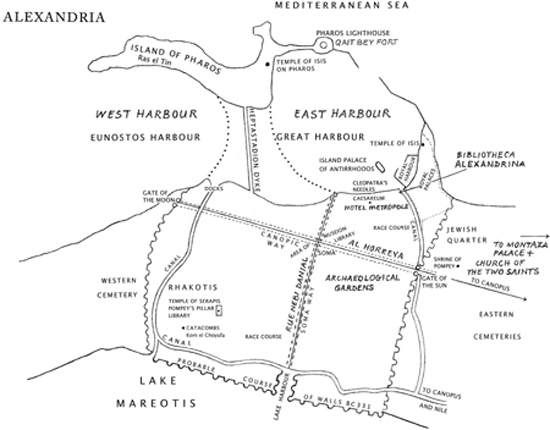

Map on pp. x–xi copyright © Leslie Robinson and Vera Brice, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1039-9

Copyright

Map

31.12.10

Arrival in Alexandria | a yellow room at Le Metropole | Maurice and the Red Tents | how Cleopatra made it happen

1.1.11

Cleopatra the First | Mahmoud and Socratis | New Year bombing | the Dead Fountain cafe | Essex clay | I look myself up

2.1.11

Slightly poisoned | Muslims and Copts | Monty’s bar | Jesus, the missing years

3.1.11

Cleopatra the Second | the rough-book | E.M. Forster and the Ptolemies | boxes of tragedies | death by needles and beaks

4.1.11

Partial eclipse | Sir Anthony Browne’s foundation | Mr G and Mr W | She Who Must Be Obeyed | blood from his nose | an arms salesman

5.1.11

V, the schoolgirl | teenage years | sodomy in Greek | burning books | a boy called Frog | Paul Simon and Jimi Hendricks (sic)

6.1.11

Cleopatra the Third | Miss Taylor | signs of a beard | Pompey’s Pillar | a bomber and a carpet

7.1.11

Cleopatra the Fourth | in Oxford | a kiss from V | Julius Caesar’s little war | a cruise down the Nile

8.1.11

Maurice gets Marowitzed | Lighthouse island | Mahmoud and the church bomb | Ides of March

9.1.11

A lesson from Holladay | Continuators | watch the office men | what classicists do | a night at The Frogs

10.1.11

Cleopatra the Fifth | an actress at St Mark’s | sex with Crissie | Maurice’s Nubian night | Socratis on Caesar | Aulus Hirtius, V and me

11.1.11

The Metropole red-and-green Ball | tied down in the tents | Frog and the Mermaids

12.1.11

Secret seventies | the Latin for hangover | Alexandrian rules | Southern Bug | somewhere on Love’s Island | alphabets in the sky

13.1.11

The middle of the story | Mark Antony waits at Tarsus | perfumed sails | successors to Caesar | a queen cannot choose her pimp

14.1.11

Cleopatra the Sixth | grey days at Big Oil | bureaucracy student | a different Antony Brown

15.1.11

Cleopatra the Seventh | space barons | V in the Red Tents | Calthorpe Arms | the Thatcher who must be obeyed | F for Farouk | Duke’s rout

16.1.11

The purpose of parties | Mark Antony’s wars | generous happenings for a general | the new Caesars

17.1.11

Queens by night and day | dreams of dogs | Romans and Alexandrians in the newsroom | leading articles | the Scargill gaffe

18.1.11

Last nights of an editor | farewell to Calthorpe and other Arms | lost notes | what happened at Actium

19.1.11

Mahmoud and the troops | death of Antony | Socratis’s mother sings | coincident cancers

20.1.11

Maurice and Cleopatra reunited | how to die without pain | E.M. Forster on the North Sea

21.1.11

V comes to Cheltenham | how to read a Latin poem | the afterlife of Romans | drink and move on

22.1.11

Last night, last words | farewell to Le Metropole | noises from the border | the right choice of driver

Epilogue

Elizabeth Taylor and the Arab Spring

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About Alexandria

i.m.

RJMG (1951–2010)

In the new year of 2011, on the eve of the Arab Spring, I was in Alexandria to complete a book about Cleopatra. With me were the remains of seven previous attempts. This time there had to be an end.

Hotel Metropole, Place Saad Zaghloul, Alexandria

This is precisely the eighth time I have begun to write this book. I am certain of that. It sometimes seems the only certainty. Here in Room 114 of the Metropole Hotel there is written evidence of all the other seven attempts, long pages and short scraps, bleached and yellowed, each piece patch-working into the bedcover as though they had always been here. I have unpacked them as carefully as though they were ancient history itself, more carefully than I packed them in London yesterday. There is no order yet. The first are not even my own words. They are Maurice’s. I have not read them for forty years, not since we were at Oxford together and I first followed his florid dictation. I have not yet unpacked anything else.

There was a red tent within a red tent within a red tent. That was what Frog said. The walls behind were grey-green and damp but in front of the canvas slit that led to the sanctuaries were dry roses. Inside the first encircling corridor the floor was warm leather. Through a second slit into a second circle there was a different carpet, silk or satin, light enough to show the outlines of the limbs that lay bodiless beneath.

These limbs were lower legs, both right legs, the soles of their covered feet fixed upwards, the faint shape of the sweating toes visible beneath the cloth. The higher parts of the thighs were out of sight inside the final red tent on the floor of the innermost chamber. There was no opening by which to pass through and see why two women, probably women, were lying face down in the hidden heart of this strange construction; or why one of each of their legs was stretched outside into the corridor as though for some reason surplus to requirements.

The only instruction was on a pink card secured by a jewelled brooch, carrying words in Greek, ‘veiled in the obscurity of a learned language’ as Edward Gibbon once noted on a similar occasion: ‘Menete! Nereidais Kleopatras Palaistra’ (‘Wait Here to Wrestle with Cleopatra’s Mermaids’).

Maurice’s story of the Red Tents was part of my fifth Cleopatra, perhaps one of the less respectable attempts. It was wilfully mysterious, a mingling of geometry, classics and pornography, as though in parody of a school curriculum. It was a shock at the time (I was easier to shock back then) but I recorded it in clear, round lettering, in a college room at Trinity, as accurately as the fumes of sherry and Old Spice allowed. At some point in the coming weeks I will try to remember more.

Maurice is the longest-serving character in this story. He was my oldest friend. We shared little in common, he the smooth one, I the rough, he the pale-faced, I the freckled, he the teller of jokes and tales, I the listener. But without always liking each other, we knew each other from the age of four. We shared primary and secondary schools, children’s parties and sports fields, college rooms and student stages. We also, for a short while, shared a passion for a dead queen of Egypt.

This was not always the same passion. Maurice’s thoughts were mostly theatrical, sensual, sexual. Tarpaulins, tapestries and human tangents were the props of a drama that lasted all his life. My thoughts were more often literary, ‘just a bit too boring’ he used to complain. In 1971 we each thought the other a bit confused. He was a man of the modern. I was the student of classical times. We argued. He is dead now, but we still seem to be arguing. By the end of this journey I want some of those arguments to have ended.

This bed is becoming crowded. The papers do not form easy categories or files. Each lies flat and alone. The earliest words are from fifty years ago, the first efforts of an Essex schoolboy; the latest from the 1980s from a classicist finding some sort of success as a journalist. Between these beginnings and ends, which show uneven patterns of progress, there are pages written in Oxford between 1969 and 1971 and at an oil company desk in London in 1976 and in the Calthorpe Arms, a crepuscular pub beside what once were the offices of The Times.

It is not a clear pattern. But I can already see debts that need to be paid, to V, an Essex schoolgirl when her contribution began, to a troubled boy called Frog, to two types of Oxford mermaid, to a grey mistress of the petroleum industry, to Margaret Thatcher and to Her Majesty the Queen, as museum-keeper as well as monarch.

There will be others to thank, an athletic schoolmaster, a not at all athletic Oxford authority on ancient plagues, a long-distance swimmer, a hero of the Anzio landings, a cancer-stricken newspaper editor and Maurice himself who also died of cancer, just before this journey, and without whose dying memories it would not be happening as it is. Tonight, on the eve of this new decade, the eve of the year in which I will be sixty years old, every remnant of my past Cleopatras is a different patch, in a fraying quilt, on a bed, beside an iron balcony, before a view over the bay where her palaces, ships and libraries used to be.

From the year 1960, when Maurice and I were nine years old, only a book title survives, Professor Rame and the Egyptian Queen. The earliest pages are from around 1963, Sellotaped in yellow stripes, an account which began, with naive confidence, at Cleopatra’s birth, in a room not far from this hotel, and with her father, King Ptolemy XII, known to obedient subjects as Dionysus, the drunkard god, and to the disobedient majority as Old Fluteplayer, the drunkard musician.

Most of my surviving words are handwritten. Only a few of the later parts are typed. Many other pages were lost entirely, left in desk drawers of abandoned jobs and buildings. But that hardly matters. At this New Year in Alexandria, there will be new words each day as though in a diary, the only reliable way that I know I will write at all. This book is not going to be a reconstruction. It is a new start and this time there will be an end.

This time there is also an instruction from the Queen herself, a signed order, the only surviving autograph from any classical figure whose life story has flourished beyond life. This document was unknown in 1985 when the last page was closed on my seventh Cleopatra. It was found at the turn of the new millennium among Roman office papers reused for stuffing mummies, Cleopatra’s single word, her last word as I intend to see it, written in her own first language, in Greek, in neat, small, upward-sloping letters, ginestho, let it be done, do as I command, make it happen.

The ginestho papyrus is of no special kind. The ink is dull. The order is securely dated like any proper product of a well-run office. The date is February, 33 BC, as we now designate our months and years, the prelude to the most dramatic time in even as dramatic a life as Cleopatra’s. The order, dictated to a secretary and presented in a fair copy for signature, is that one of her most loyal protectors should be freed from certain taxes. She takes up her pen at a forty-five-degree angle, routinely, relaxedly, running the last four letters together in a single fluid stroke, and writes the ginestho on the decree that Mark Antony’s general, Publius Canidius Crassus, and his heirs in perpetuity, may export each year from Egypt 300 tonnes of wheat and import 130,000 litres of wine without paying tax to her or to her children.

This is a tax exemption for the far future from the Egyptian head of a great Greek family who has entered Rome’s civil wars, world wars then, with every intention of being on the winner’s side. Her man, Canidius, commands the greatest army of the time. She herself commands the most massive personal treasury. The odds are that her lover, Mark Antony, will soon defeat his rival Octavian for the leadership of the Roman world, the legacy of her earlier lover, the assassinated Julius Caesar. She may even choose to exert that leadership not from Rome but from her own palace here – where tonight the cars honk ceaselessly in the square, the birds and beggars scratch on the beach, and the Nile waters still mingle, more sluggishly now, with the Mediterranean sea.

‘Make it happen,’ she wrote. Her word went out into corridors of bureaucrats and bandits, corrupters and corrupted. Her fellow Alexandrians would never be as admired as much as the ‘classical’ Greeks from Athens who lived four hundred years before. Nor would they be as feared as the Romans who conquered and followed them. But Cleopatra’s people were bureaucratic pioneers, masters of the catalogue and file, inventive manipulators of myth, model office workers as well as models for much else in the ways of life they exported to the future. Although Cleopatra signed orders for music and poetry, wars and executions, medical experiments and monumental theatre, exempting a man from taxes was in no way a smaller matter than these. Revenue made things happen; or stopped things happening.

Of course, this ginestho soon became an unnecessary concession. Within two years Cleopatra was dead. The Romans took all Egypt for themselves. Her promise had become a bribe that she need not have made, a few words on a fragile piece of papyrus, a part of the rubbish used to fill the space between a body and a coffin. For the next two thousand years it would cushion an unidentified cranium against a painted piece of wood, a lesson in recycling from an age resourceful in the arts of reuse. Only in the last ten years has it become a thing of resonance once again, one of those rarest of objects, a direct connection between a great queen and those of us who have so long tried to make her our subject.