This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2015 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact sales@overlookny.com,

or write us at the address above.

Copyright © 2015 Mary Louise Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

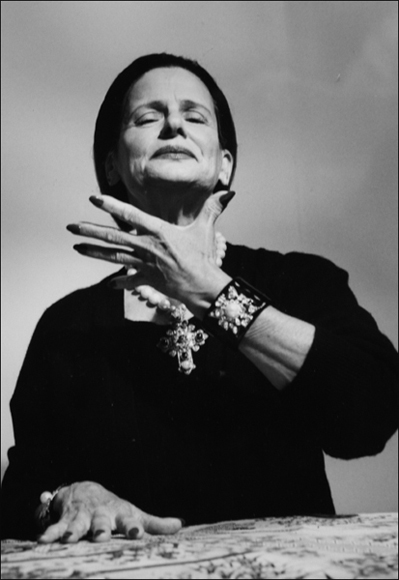

Frontispiece photograph copyright © The New Yorker

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1224-9

Copyright

Dedication

1989

1940s

1950s: New York City

1950s: Nightclubs

1991: First Reading of Full Gallop

The Village

My Last Office Job

1957: My First Theater Job

The Village Club Scene

The Threepenny Opera

George Furth

Full Gallop

More Full Gallop

1959: Julius Monk

Lovelady Powell

1960s: Television Commercials

Julius at the Plaza

1963: Hot Spot

Twice Over Nightly

Full Gallop

Acting Lessons

1964: Sherman, Connecticut

Oklahoma! Tour

1964: Bad Times

1965: Flora the Red Menace

1960s-1970s: Industrial Shows

The Marriage

Auditioning

Singing

Wally Harper

1991: A Reading at Playwrights Horizons

André Bishop

Television Commercials

Unemployment

Unemployment Insurance

The Call

The Cosmopolitan Club

1969: Cincinnati

Full Gallop

1972: Gypsy

Sally Cooke

Going On

On the Road

The Mink

1993: Full Gallop Juilliard Benefit

Ellis Rabb

Doris Dowling

1976: The Royal Family

May 1993: Woodstock

June 1993: Bay Street

Pilot Season

L.A. in the Seventies

McGraw’s

Summer 1994: The Way of the World

1977: One Day at a Time

Earnest

1978: Alice at the Public

More Hugh

1981: Fools

1982: Zelig

1982: Whorehouse

1980s: Mega-Agents

Being Packaged

Green Card

Nonprofit Theaters

Fired

November 1994: Full Gallop with the Allens

Theaters

1984-1985: On the Road Again

Odd Couple Diary

On the Road (Again) ’84–’85

L.A.

1990

Full Gallop

Momentum

The Inevitable Ending

The Chair

Finally

After Full Gallop

1999: Full Gallop in London

2006: Grey Gardens

More George

The Obies

The Tonys

Nowadays

Who’s Who

Thank You

About the Author

30 BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS

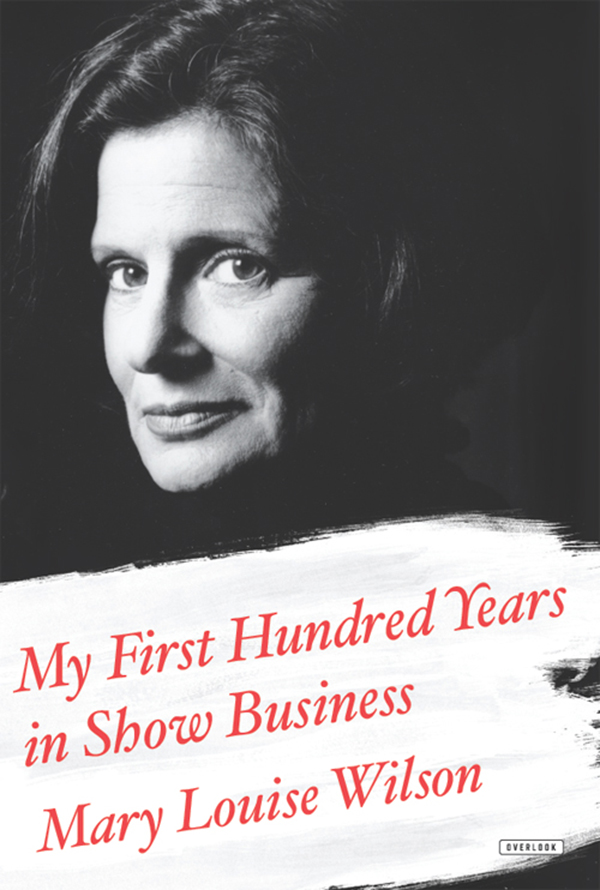

Mary Louise Wilson became a star at age sixty with her smash one-woman play Full Gallop, which she co-authored, portraying legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. But before and since, her life and her career on stage—including the Tony Award for her portrayal of Big Edie in Grey Gardens—as well as film and television, has been enviably celebrated and varied.

Raised in New Orleans with a social climbing, alcoholic mother, Mary Louise moved to New York City in the late 1950s; lived with her gay brother in the Village; immediately entered the nightclub scene in a legendary review; and rubbed shoulders with every famous person of that era and since. My First Hundred Years in Show Business gets it all down, story by tantalizing story. Yet as delicious as the anecdotes are—and they truly are—the heart of this book is in its unblinkingly honest depiction of the life of a working actor. In her inimitable voice—wry, admirably unsentimental, mordantly funny—Mary Louise Wilson has crafted a work that is at once a teeming social history of the New York theater scene of the past fifty years and a thoroughly revealing and superbly entertaining memoir of the extraordinary life of an extraordinary woman and actor.

To my friend and guide,

Dennis

I was swimming around in Edwina’s pool having such a nice, refreshing time, when she said “You know, Diana, your future’s behind you.” “Your future’s behind you!” I nearly DROWNED!

—Diana Vreeland, D.V.

I WAS SITTING AROUND A TABLE WITH THE REST OF THE CAST ON THE first day of rehearsals for Macbeth at the Public Theater when the director rose from his chair, turned to me, and said, “First Witch? I’m giving your chestnut speech to the younger, prettier witch.” Now, I wasn’t crazy about playing this witch; let’s face it, it’s a generic crone role! But I hadn’t worked on the New York stage in a long time.

For the past few years the only parts I was getting called to read for were washroom attendants and bag ladies on television. I was even going up for parts against actual bag ladies. I had gone from featured roles on Broadway to playing parts labeled “Woman” with lines like “Hello.” So now I was telling myself well at least I’m first witch. Then this director took away the one thing that made me first: the chestnut speech.

I was shocked. I thought the best thing about performing a dead playwright’s work was that your lines couldn’t be cut. A director could make me wear a hat that covered my face or a farthingale that wouldn’t fit through doors, but nobody was going to fiddle with my words. Especially not Shakespeare’s. Not that I had a clue what the chestnut speech was about, but it had lovely, tongue-rolling phrases like “aroint thee” and “rump-fed runyon” and “mounched and mounched and mounched.” And now this guy was stripping me of my epaulettes in front of the whole damned company. To make matters worse, the witch he gave it to really was young and pretty, so he was not only rewriting Shakespeare, he was having a cheap laugh on me. This wasn’t a career I was having, it was an exercise in humiliation.

How the hell did I end up here? I felt it was my fault, that I had caused or allowed it to happen. At the same time, I certainly didn’t feel like I belonged down here.

There’s an old refrain about the five stages of an actor’s life:

1. Who is Mary Louise Wilson?

2. Get me Mary Louise Wilson.

3. Get me a Mary Louise Wilson type.

4. Get me a young Mary Louise Wilson.

5. Who is Mary Louise Wilson?

I was somewhere between stages four and five. I was dimly conscious of my own culpability, but at the same time I bristled at being taken for, mistaken for, a modest talent only suitable for maid parts.

You have to have a dream of something, you know, if you’re going out to buy a pair of bedroom slippers, you have a dream of what you want …

FOR A FEW MONTHS NOW, MY FRIEND MARK HAMPTON—NOT THE deceased decorator, but the very funny and very much alive writer Mark Hampton—and I had been fooling around with the idea of writing a play about a woman named Diana Vreeland. She had been a powerful magazine editor and well-known figure in New York social circles for decades. Now Mark had become fascinated by recent newspaper accounts of her being blind and bedridden, her once jet-black hair turned white, and her jewelry and other personal effects being auctioned off at Sotheby’s. We were both touched by her sad fate. I picked up her book, D.V., a collection of her reminiscences and pronouncements as edited by George Plimpton, and reread it. I had read it years earlier, when it was given to me by a pal, Nicky Martin. At that time I simply thought it was wonderfully silly. We took turns reading passages aloud and keeling over laughing. This time, though, I fell in love with her unique use of language.

Just for kicks, I sat in a chair across from Mark and read a couple of her stories aloud. We looked at each other. This was great stuff. We knew it. We talked about the possibilities and the difficulties of writing about somebody still living. Mark had already been to hell and back writing a musical about the Boswell Sisters while one of them was still alive. Besides, I doubted we could get permission. Then one morning we came across her obituary in the Times. August 23, 1989. It hit me then that if we didn’t make a move, somebody else was going to get their hands on that book and I would regret it for the rest of my life. So now, sitting stewing in the rehearsal hall, it occurred to me that I had nothing left to lose. On the first break, I went to the pay phone and called a lawyer I knew about getting the rights to D.V. I was going to write a play based on this book, and I was going to perform it in broom closets, if necessary.

IN THEATRICAL CIRCLES, MENTIONING THE NAME “MACBETH” IS believed to bring on extremely bad luck. If an actor utters it or any line from the play inside a theater, he or she must perform a ritual. There are variations of this ritual, but the one I know is to spit three times as you turn around three times in the dressing room doorway. It is consequently always referred to as “the Scottish play.” Directors of the Scottish play seem to me to get hung up on the witches. The witches are their big, if not only, chance to exercise their directorial style. I’ve seen or heard of the witches appearing as pretty fairies, giant puppets, or male goth rockers. They can be played as real or they can be supernatural. Our director informed us that we were real, and that we lived off the refuse of the battlefield. In other words, we were bag ladies.

Maybe Richard felt bad about taking away my chestnut speech, because the second week he gave me a tumbrel. The idea was that I would lug Banquo around in it. This tumbrel looked like something out of The Flintstones. It had big clunky wheels and on its trial run down the aisle it got stuck. It was built too wide. I saw the set designer slap his hand over his face. After that I just lugged Banquo on and off upstage left. I can’t remember now where I was lugging him to, or why.

A week after my first call to the lawyer, he called back; our quest for D.V. was hopeless. The famous agent Swifty Lazar claimed “planetary rights.” My heart sank. Who would give me the rights anyway? Me, a fiftyish, thoroughly demoralized, demoted first witch? I didn’t have the standing. The awards. Not to mention the shoes.

Something was definitely amiss in the Public Theater’s prop department. We witches were told we would have bloody animal parts and entrails for the “boil and bubble” scene. What we got were little sticks with feathers glued to them, and our entrails were surgical hoses that bounced unconvincingly. Our cauldron was the size of an ashtray with a sliver of dry ice inside that refused to boil or bubble during our incantations. It waited until our backs were turned to burp a trickle of smoke, like a rebuke for being yelled at. The audience giggled.

The lawyer called again; apparently Swifty had been speaking allegorically. The rights to D.V. were in the hands of the Vreeland family. Their lawyer was George Dwight. We called Mr. Dwight and he invited us up to his office. He was very cordial, a gentleman of the old school. He seemed intrigued by the idea of a play about Vreeland, perhaps sensing money to be made, but we would need the approval of her sons, Tim and Frederick. He said he would contact them. Things seemed possible now. Mark and I went down the street to an expensive Italian restaurant and ate an enormous lunch.

IN THE SECOND WEEK OF PREVIEWS, A DESPERATE, SWEATY RICHARD suddenly decided that the witches controlled the weather. Confusion among the witch ranks: we thought we were real people. Nevertheless. He gave us instruments: a little drum for Second Witch, a triangle for Third, and a recorder for me. We reminded me of a kindergarten band. Three little witches from school. We were supposed to summon wind, thunder, and lightning with our instruments, but the sound and light cues consistently came too early or too late, causing more giggles from the preview audience.

… and as I can never find a pair of bedroom slippers I can get into, I’ve only got the dream. Not the slippers. —D.V

GEORGE DWIGHT CALLED. THE SONS WERE INTERESTED, BUT A grandson, Alexander, objected to the idea of his grandmother being portrayed onstage. It was a fact that drag queens were “doing” her everywhere, and he feared, quite rightly, that we would make her an object of camp. So, down, down I went, “like glistering Phaeton, into the base court.”

THE NIGHT BEFORE THE LAST PREVIEW, RICHARD, HAIR ASKEW, wild-eyed, said to me, “You know what I want.” I was very much afraid I did. “You want me to appear in the sleepwalking scene as the witch,” I said. “Right,” he replied.

I had been going along with the tradition of doubling as Lady in Waiting in the sleepwalking scene. Nightly, I traded my rags for a gown and a wimple. But now he wanted the hag standing behind Mrs. M. while she bemoaned her fate. “Give me one good reason!” I snapped. “Well,” he thought for a minute, “the Macbeths are having a servant problem.” I went to Lady M’s dressing room and told her what he wanted me to do. She was a young thing, fresh out of Juilliard, possibly dating Richard. She didn’t see a problem. “But it will steal focus!” I shouted. Shrug, no worries.

My actor buddy and occasional personal analyst John Seidman was staying with me at the time. I consulted him the next morning over coffee as I lay in bed and he sat alongside me in his briefs. I wanted to call Actor’s Equity, but John advised going along with it. “He won’t keep it in,” he said. He was right. When I appeared that night in my foul rags, audience heads swiveling from Lady M back to me created a susurrus that nearly blew her candle out.

Give ’em what they never knew they wanted. —D.V.

BUT I DIDN’T GIVE A DAMN WHAT HAPPENED ONSTAGE NOW, BECAUSE Dwight had just called back again: the sons had decided to ignore the grandson’s objections he said, they were in favor of a play about their mother. Oh joy! And then he said “Frederick Vreeland, ‘Freckie,’ wants to meet Mary Louise.” Oh, God! This had not occurred to me. Of course he would want to see what I looked like! How could I possibly pass muster? How could I ever convince him I could play his mother? This woman dominated the fashion world for three decades. What to wear? What to wear? That persistent cry. This was the eighties and my uniform was hip-hugger jeans and turtlenecks. I no longer had a blueprint for myself in a dress. I ended up buying something in a mall—a noncommittal black linen sack and a pair of excruciating black leather pumps—and when I got it all on, combined with a pair of black stockings, I looked like somebody’s Sicilian mama.

It was a boiling hot June day. The vestibule just outside the apartment door was lacquered red, and on the wall hung a painting of young Diana in a dress with a floating white collar. I stood there in my widow’s weeds, stockinged legs itching, feet aching in my hard leather heels. I was back in dancing school, standing against the wall in a velvet dress that didn’t fit, my precipitate breasts squashed under the bodice, my size-eight Mary Janes looming below me.

I rang the bell. Freckie greeted me wearing tennis whites, shorts, and a polo shirt. He didn’t give my wardrobe a glance. He was gracious and easy. He took me to lunch around the corner. He was funny like his mother, and he chatted freely about her. He said she was not a very good mother—she was not around and had no sense about money—but when I told him that I revered her, he looked surprised and pleased. He told me that even when she was ill and bedridden, she continued having dinner parties. The maid would serve and the guests would talk to her through her closed bedroom door. Freckie’s comment was, “Mom never liked to appear unless she was at full gallop.”

After a few agonizing days, Dwight called to say I had passed inspection. Mark and I went to his office to sign the contracts giving us exclusive rights to D.V. Oh joy, oh rapture! We floated out of the office and down the street to another expensive restaurant and ate another gigantic lunch.

Some eras I’ve known are as dead as mud. But they were so great. —D.V

I MAY HAVE BEEN BITTEN BY THE VREELAND BUG AT A VERY EARLY age. Growing up in New Orleans in the forties, I was fascinated by the women my mother invited to our house to play bridge: elegantly dressed ladies with their little hats, their bright red lips and nails, their husky voices and phlegmy smokers’ coughs. The way the metal clasps on their purses clicked open and closed importantly, their lipsticked cigarettes smashed in the ashtrays. Looking back, I realized that their drawls had the same touch of Brooklynese that Vreeland had. They weren’t necessarily pretty; one or two of them looked like wizened little monkeys, but chic little monkeys, with diamonds in their ears. And they were often funny. I was an untidy child, big for my age with scabby knees and exploding hair, yet I longed to be like these women, to be glamorous and funny.

We moved to New Orleans from Connecticut when I was seven. My mother found and renovated an old house in the Garden District: white columned facade, high ceilings, marble fireplaces, and living room windows that went right to the floor. The rooms were beautifully furnished. My mother had a genuine talent for decorating. She had to have the best and the latest of everything. I think we had the first automatic dishwasher in the city; when turned on, it “walked” across the kitchen floor, scaring the hell out of the cook. But this house was to be my mother’s dream fulfilled, the stage for her career as a New Orleans society hostess. Where the money came from to pay for all of it, none of us would ever know. When I looked at the mountain of bills cascading off her desk, I could feel the anxiety flowing out of it. It may be that some people were never paid. My father had been hired as an associate of the esteemed Ochsner Clinic, but he was a tuberculosis doctor, the “poor man’s disease.” I’m sure his salary was modest.

My father was handsome and charismatic. I was madly in love with him, but he stayed aloof behind his newspaper while our mother tyrannized us. My mother’s mother was an Anglophile who worshipped the King of England and the little princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret Rose, who called the Queen “Mummy.” Consequently, our mother instructed us to call her “Mummy.” My brother used to say, “Mummy is the root of all evil.” To us, she was a regular Hitler giving out endless orders and rules about manners: “Sit up,” “Sit down,” “Curtsy,” “Say ‘Sir’ and ‘Ma’am.’” Even now, in my eighties, I start to stand up when an adult enters the room. My mother taught us when sitting down at the dinner table to unfold our napkins and put them in our laps. I somehow missed the order about what to do with it when dinner was over, and to this day when leaving the table my napkin slides to the floor and I trip over it.

Mummy’s father was a distinguished Presbyterian minister, and she saw herself as descended from royalty. She was obsessed with social rank. She wasn’t ever where she thought she ought to be in the hierarchy, and her unhappiness was a black cloud over the family. Her feelings were forever getting hurt and her tears were a constant oppression. There was nothing we could do to stop the flow. It trickled down on us and divided us, and made us cruel. My father teased my mother until she cried, my older brother and sister teased me until I cried, and I teased the dog until she bit me.

The one thing that kept us all from killing each other was humor. We shared a highly developed sense of the ridiculous. My father was a champion scoffer, and he could not refrain from teasing our mother for her pretensions. We not only had a cook (in those days most Southern middle-class families had cooks), but also a butler. Family dinners got fancier and fancier, with linen napkins, candelabra, salad plates, salad forks, and finger bowls. When he got a load of the finger bowls, my father twitted, “What’s this for, dear? For germs? I washed before I came to the table. What? What?”

Watching our father tease our mother thrilled us children. One night she started to say, “When I was abroad—” when he interrupted “You were a broad, dear?” We became hysterical. She had her moments. One night after some hectoring, the butler entered with dessert and placed it in front of her: molded grape Jell-O on a crystal plate. She rose from her chair, stood for a moment staring dreamily down at the quivering mound and then she slapped it. She slapped it so hard she broke the crystal plate and to our utter delight bits of Jell-O shot all over the table. Some even hit the wallpaper. She wailed, “I always wanted to do that!”

Another time the family was spending a Fourth of July weekend at a fishing camp and while Mummy was visiting the outhouse, my brother threw a lit firecracker onto the tin roof. There was a terrific explosion followed by dead silence and then Mummy stepped out. With great dignity she murmured, “it must’ve been something I et.”

My mother inherited her timing from her minister father, who incidentally was an actor until he realized he would never get leading roles because he was short and his head was too big. He went into the pulpit instead and thrilled his congregation by reading from the Bible in a roaring baritone, tears pouring down his cheeks. He could be very funny at his own dinner table, and his grandchildren inherited his timing—a blessing from the grave. It’s innate; you either got it, or you ain’t, and we got it.

My brother and sister were both very funny people. Hugh was four years older than me, and Taffy was five. I longed to be accepted by them, but they weren’t having any of that. We had a costume trunk in the attic. Didn’t every family? In there were World War I puttees, top hats, ancient evening gowns, tailcoats, and fur pieces. It was family tradition to “dress up” on party occasions. One night, Hugh in an old tailcoat and Taffy in a tea gown danced a wild tango around the living room to a recording of “Jealousy,” and my stern father laughed so hard tears ran down his face. I tried to join in, but was roundly rejected. I was only funny when I didn’t mean to be. The sight of me wearing my dress inside out or my shoes on the wrong feet or coming home from kindergarten inexplicably covered in green paint made my siblings roar.

I don’t recall ever being taken seriously. Tears were “crocodile tears,” and temper tantrums—usually the result of being ignored—meant being sent to my room. To solitary.

When we were little, Hugh was constantly trying to kill me off. We spent summers in Connecticut with a bunch of cousins, and we used to play in an old boathouse down by the lake. It had a big upper room once used for Sunday bible meetings. Down below, there were rowboats rotting in the muck. One day, Hugh made up a game called “Heaven and Hell.” The upper room was Heaven, the muck was Hell, and he was God. If you did what God told you to do, you got to go to Heaven and run relay races, and if you didn’t, you went to Hell in the muck. I was five and Hugh was nine. He was letting all our cousins into Heaven. When it was my turn, he told me the next time a car drove by to pull my pants down. A car drove by, I pulled my pants down, and he sent me to Hell anyway.

In later years, if we were playing Monopoly and I somehow acquired Park Place and Boardwalk, Hugh would put hotels on his Railroads illegally and charge astronomical rents. When I squealed, he said, “Don’t be such a brat,” and I gave in. I somehow knew he had to win.

Like our mother, Hugh had a royalty complex. From the time he was born, he was captivated by kings and princes and popes, and he loved despots and palace intrigues and panoply. When he was fourteen, he retired from the family to an attic room at the top of the house, only leaving it for school and meals. He was a brilliant student, top of his class in English and physics, and he was endlessly creative with things mechanical and structural. His room, which I was once allowed to enter, was filled with gadgets, buzzers, bells, and a miniature theater with tiny spotlights and motorized curtains. He taught himself to play the piano; once in a while he descended from his lair, sat at the living room grand, and banged out “The Great Gate of Kiev” so loud the table lamps jumped. I didn’t understand at the time that he was tortured because he was gay and his father treated him with contempt. He was filled with fury against both our parents.

As a grown-up he was both erudite and very funny, holding forth on such topics as Tristan and Isolde from the point of view of “poor King Mark,” or on how Desdemona caused all the trouble because she lied about the handkerchief. At the same time, he could be physically hilarious, imitating a big-bottomed premiere danseur strutting around the stage or a mentally challenged king bopping his subjects on the head with his scepter. He considered being an actor for a while, but decided it wasn’t a respectable occupation for a man. He became an English professor instead. Thank God. I could not have followed him onto the stage.

My sister Taffy had as little to do with me as possible while we were growing up. “Stay out of my room!” “Don’t touch my things!” She was dainty, fastidious, with small feet and clean fingernails and all the boys fell in love with her—the exact opposite of me. Her funniness didn’t seem to threaten her feminine charm. She could convey her opinion of something pompous or silly-looking with a grunt that made people burst out laughing. And she could move her body around like a soft custard, dancing to Zydeco, pallumping around the stage. She settled in New Orleans, raised three children, and was a much beloved actress in community theater productions. We stayed connected through the years, although she, like Hugh, couldn’t ever quite bring herself to acknowledge my success. For years she sent me news clippings about actresses who had become drunks or thrown themselves out of windows.

Later, when the family came to see me perform, they were invariably at a loss for words. If I asked them how they liked the play or my performance, they looked uncomfortable and muttered something about the set or the music. When I once asked my sister about this, she said, “Well, maybe we’re embarrassed.”

It was inevitable that I should grow up believing the most important thing in the world was to make people laugh. It was the only thing. I had to get laughs. I got them in school by telling stories about myself. When people laughed I felt exonerated, relieved of my shame. At the same time, I was reinforced in my sense of lacking substance.

I often think of something I once read in a Reader’s Digest: A colonel in India had a pet monkey that was pooping all over the house. The colonel proceeded to spank the monkey and throw him off the balcony every time he misbehaved, until finally the monkey learned after pooping to spank himself and throw himself off the balcony.

I constantly informed others of my flaws. It became a lifelong habit, a tic I wasn’t even aware of. When anybody attempted to see something in me, I immediately felt it necessary to disabuse them. I had to keep my light under a bushel. On the other hand, when people took me at my word, I was furious. They were supposed to snuffle out my true worth without my help.

As an adolescent I was always getting lost, taking the streetcar the wrong way or taking detours to school, seeing men with their penises out and being terrified they would follow me.

I was ten when my mother embarked on the first of a succession of illnesses that would continue for the rest of her life. She developed an embolism in her leg and, on doctor’s orders, she lay in bed in a darkened room for six months. Doctors also advised a couple of drinks a day “to keep her veins open.” My siblings were old enough to escape after school to friends’ houses. I came home to an otherwise empty house and my mother’s moans and calls for more ice. I was in the sixth grade at Louise S. McGehee’s School for Girls and I was out of control. I shouted in the halls, I couldn’t stop talking, I was always in hot water because of something I said. One day I was called to Miss McGehee’s office. Mummy was sitting there. She had gotten out of bed. She was wearing a fur piece I had never seen before. It seemed I had bullied a classmate so much that she had some kind of breakdown, and I was being expelled. Driving home, Mummy addressed the cosmos: “Any other mother would have thrown herself off a bridge.”

BUT NOW HERE IS ONE OF THOSE MEMORIES THAT CONFLICTS WITH this view of myself as a totally despised miscreant. I must have been about twelve when I memorized the entire first act of Arsenic and Old Lace, playing all the roles—I practiced the lines in my bedroom closet so my siblings wouldn’t hear—and I performed it, using a different voice for each character, at a parent-teacher meeting. It was a success, I repeated the performance at another adult gathering, and again it went over well. I don’t recall the circumstances, who put me up to it, but it must have been an adult who noticed something good in me.

After this I was invited to enter a speech contest at a tiny college in northern Louisiana. My competition was a buxom girl who performed a dramatic poem called “The Highwayman.” While reciting it, she impersonated the maiden with hands tied to the bedpost behind her so that with each cry of “The highwayman riding comes, riding comes!” she thrust her ample bosoms forcefully this way and that way, and she won first prize. This was my first taste of what I would be up against, so to speak, in future years. I came in second. My diploma read, “Second Prize (Comedy Division).” That last bit annoyed the hell out of me. It still does. Why is comedy not as respected as drama?

AROUND THE AGE OF FIFTEEN I TURNED INTO SOMETHING OF A swan. I caught my family’s sideways glances. They stopped laughing at my looks, at least. High school was more fun because of boys and dances. We were dancing to “Moonglow,” “Mam’selle,” and “Prisoner of Love.”

Everybody read Life magazine in the forties. I loved the series “Life Goes To.” The picture stories of New York City made a huge impression on me. One was a day in the life of a fashion model. The first photo showed a young woman gazing out her window while holding a cup to her lips. The caption read, “5:30 A.M. Betsy takes her last sip of coffee before heading out for her 6 A.M. modeling job.” The next photo showed her standing on the curb with her hatbox in one hand—all the models carried hatboxes instead of purses—and waving with her other hand. “5:45 A.M. Betsy hails a cab” and so on through her day. There was “Life Goes to Broadway,” which showed a young Julie Harris at an audition and a method acting class. I was also avidly listening to recordings of Oklahoma! and South Pacific.

Mr. Fredericks, the dour high school history teacher, had been assigned, I’m sure against his wishes, to put together a girl’s cheerleading team. With some reluctance, he let me join. “You have great energy,” he said, “you just need to channel it!” I didn’t realize how much my insides jarred with my outside. I had a large presence, which was often scary to the gentler sort. Voice, gesture, everything about me was big. We were holding a pep rally for the football team in the auditorium because it was raining. In my new capacity as cheerleader, I got up on the stage and yelled, “Leeeet’s go!!!” To my astonishment, the entire auditorium responded with a tremendous roar. Usually when I yelled, people yelled back “Shut up!” “Pipe down!” Now, for the first time, I experienced a positive power I didn’t know I had.

One day in senior year, Mr. Fredericks stopped me in the hall and asked where I was going to college. I had no plans, my grades were atrocious. I probably would have followed the plan my parents had for me. Along with the other “nice” New Orleans girls, I would have gone to Newcomb College for two years, then made my debut, then probably married some drunk with an old family name, and ended up divorced or dead, if Mr. Fredericks hadn’t said, “You should go to a college with a good theater school. You have talent.” Nobody, no adult, had ever said such a thing to me. I applied to Northwestern University’s School of Speech, and to my complete surprise, I was accepted.

NORTHWESTERN STUDENTS STRUCK ME AS CORNY. HORRIBLY RICH, Midwestern hayseeds. Cashmere sweater sets, Buick convertibles, mandatory sorority serenades, and Frankie Laine’s “Mule Train” and “Cry of the Wild Goose” gave me the pip. Everybody drank Moscow Mules.

Question: Is mimicry the same as acting? Is the ability to become another person, to imitate, less than the ability to create a character from a written script?

By the end of freshman year, competition had knocked all the wind out of me. In New Orleans I had been the unchallenged clown among my classmates. Here, in the acting class you had to push and shove your way past everyone else to get your name up on the board in order to do a scene. And the scenes were from Odets and Lorca and Ibsen. I only wanted to be funny. I wanted to be Ado Annie. I came home on vacation and went to see Mr. Fredericks. I told him I felt like I wasn’t an actress. He shrugged and said, “Well, maybe you’re just a mimic.” I was crushed, to say the least. “Just a mimic” haunted me for years afterwards. I lacked the depth to be an actor. I couldn’t cry on cue.

WHEN THINGS WEREN’T WORKING OUT FOR ME IN THE THEATER department, I switched my focus to English literature. Northwestern had wonderful English professors. I had never read a good book. In high school I passed up Silas Marner on the reading list for my mother’s copy of The Lovers of Lady Bottomley, among other bodice-rippers she got from the library. I pored over This Is My Beloved, a steamy missive she had hidden in her underwear drawer. Now, I was devouring Madame Bovary, The Magic Mountain, Crime and Punishment, and Ulysses. The exams were generally “discussions”: “Discuss Hans Castorp’s declaration of love to Clavdia Chauchat”; “Discuss Emma’s need for luxury”; “Why did she take a lover?” My God, “discuss!” I was the queen of bullshitters. I was getting As with red exclamation points on my papers. I discovered I had a brain. I decided to be an intellectual. I quit the sorority, played Brahms and Beethoven symphonies at top volume in my dorm room, and my roommate and I wore trousers and hung out in bookstores with guys who played chess.

This was when my brother Hugh began to accept me into his world. We were very much alike in looks and wit and rage against our parents. He saw me as his acolyte, I saw him as my lifesaver.

AFTER GRADUATION I CAME STRAIGHT TO NEW YORK AND MOVED into an apartment on West 114th Street with Hugh and his girlfriend Phyllis Starr. The apartment was dubbed “Fuchsia Moon Flat” because one of the Princeton aesthetes Hugh hung out with had said, “People like us meet only once in a fuchsia moon.”

Philip, Wayne, Joel—these were his literate, witty young friends. I was thrilled to be included in their circle. They were my introduction to camp. There was much imitating of homosexual behavior, much wrist-flapping and lisping, “Get you, Ella.” I thought it was so funny. I went around flapping my own wrist and lisping, “Get you, Ella.” It didn’t strike me as odd, much less offensive. I certainly didn’t think that any one of them might be homosexual. I mean, here was Hugh’s girlfriend, and then Philip kept flirting with me. Philip had a plummy voice and a mellifluous laugh; he kept grabbing me and tossing me around, gurgling, “I’ll tame you yet, you gypsy wench!” Of course they were gay, but this was the fifties. You might as well have had smallpox.

We bought the furniture for Fuchsia Moon at the Salvation Army store on 125th Street, a veritable gold mine of mahogany dinner tables, bureaus, elaborately carved throne chairs, Tiffany lamps, and fumigated mattresses, as well as twenties evening gowns, fur coats, beaded dresses, Bakelite bracelets, feather boas, and fedoras that were bought for a song and put into the “drag chest” in our living room. Hugh, naturally, formed a court. He made crowns out of wire and beaten tin and we were given titles. Philip was the Duchess of Larchmont, Wayne the Duchess Biddy de Ripon, and Joel, Princess of Palestine. Phyllis was Princess of Panola because she grew up on Panola Street, and I was the Marchioness of Mauweehoo, which was the name of the lake in Connecticut.

Every morning the three of us put on our little seersucker outfits and trotted out the door to work. Every night we came home, climbed into the “drag,” drank beer, and danced around the living room to Berlioz or Prokofiev or some other bombastic classical piece. There generally were a few straight friends—college acquaintances—hanging out on the sofa enjoying the show. Hugh sashaying around in a strapless evening gown with chest hairs sprouting from the top was a sight to behold. He was too hilarious to be seriously fruity. He was never serious about anything. It was forbidden. He talked about something he called the “emotionless criteria.” I didn’t completely get it, but the message sank in: no talk about your inner life or the state of the world, and no discussion of feelings.

I was terrified of the city. I had to get a job, but I couldn’t imagine who would hire me, much less actually pay me. I was afraid I might starve to death. My roommates, both English majors, had editorial jobs in publishing. I figured the only thing I could be was a secretary but you had to know shorthand to take dictation. I tried pretending to do it on a couple of job interviews with humiliating results so I got my parents to cash in a WWII war bond they had taken out for me and I enrolled in a summer secretarial school on the fifteenth floor of the Radio City Music Hall building. In the classroom I became the same disruptive element I had been in high school, giggling over the corny inspirational sayings posted on the blackboard and being generally obnoxious. We were in a room high above the city taking dictation from the elderly instructor who would mutter “Dear sir,” “Dear sir,” and immediately drift off to sleep. We sat there, vacant summer sky floating outside the open windows and the voice of Mario Lanza singing “Be My Love” wafting up from the Music Hall far below until I couldn’t contain myself any longer and burst out laughing and he woke up glaring at me. Needless to say I didn’t graduate.

magazine, 1954