First published in hardcover in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2016

by Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact sales@overlookny.com,

or write us at the above address.

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

E: info@duckworth-publishers.co.uk

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact sales@duckworth-publishers.co.uk,

or write to us at the above address.

Copyright © 2016 Yael Neeman

First published in Hebrew in 2011 as Hayinu He‘atid

by Ahuzat Bait Publishing House, Tel Aviv

English language translation copyright © 2014, 2016 Sondra Silverston

Poems and songs translation copyright © 2016 Jessica Cohen

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-1386-4

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Thanks to Avri Sela

References

About the Author

WE WERE

THE FUTURE

A MEMOIR OF THE KIBBUTZ

YAEL NEEMAN

TRANSLATED FROM THE HEBREW BY SONDRA SILVERSTON

With 33 B&W Images

THE KIBBUTZ MOVEMENT is one of the most fascinating phenomena of modern history and one of Zionism’s greatest stories. Several hundred communities attempted to live the ideas of equality, freedom, and social justice by giving up private property, individualism, and the “bourgeois” family unit to create an Israeli utopia following the Holocaust—the only example in world history of entire communities voluntarily attempting to live in total equality. However, for the children raised in these communities, the kibbutz was an institution collapsing under the weight of an ideology that marginalized its offspring to make a political statement.

In this spare and lucid memoir, Yael Neeman, born in 1960 at the height of the kibbutz movement, skillfully captures the defining memories of her childhood and adolescence, which were shared by hundreds of thousands of Israeli children in the kibbutz. Using the collective narrator “we,” Neeman recounts the experiences of the children of the kibbutz movement, as well as the sociopolitical circumstances within which the communities functioned. We Were the Future is more than a compelling personal account of growing up in the kibbutz movement; it is an unstintingly honest examination of the price of equality and a new lens through which to see the history of Israel.

We were always telling ourselves our story.

Compulsively. Out loud. All the time. Sometimes we got tired even before we began, but we still told it for hours. We listened to each other intently. Because every time we told the story we learned new details. Even years later, when we were no longer there.

For example, we hadn’t known that some of the kids from the Pine group, who were five years older than we were, worked with the cowboys. And that they lived in an enclave of Hungarian rural life within our kibbutz. We hadn’t known that instead of saying good morning and goodnight, they said lofes (a horse’s prick). We hadn’t known that Itai, one of the Pine group, freely rode a horse around our hills when he was only six years old.

The stories were told only orally, contrary to all written rules. They rose from the lawn sprinklers that surrounded the dining room, from the scorched remains of our Crusader fortress, from the cracks of the beautiful, narrow stone sidewalks. We told our stories with shining eyes. We said, “It’s unbelievable that they used to slaughter the cows on the ramp, right in front of us, that they used to decapitate the chickens like it was nothing at all,” but we spoke as if those were the best years of our lives.

And they really were the best years of our lives, dipped in gold, precisely because we lived in below-zero temperatures in the blazing heat of an eternal sun. We greeted each new day with eagerness and curiosity. We were wide awake in the morning and wide awake at night. We skipped and ran from place to place, our hands sticky with pine tree resin and fig milk. We were so close to each other, all day and all night. Yet we knew nothing about ourselves.

We always told our story, even then, in the children’s house on nights when the full moon glowed orange in the sky. Even then, day and night, so we could sleep, so we wouldn’t sleep, we’d sit in the corridor at the doors to our rooms or on our beds and exaggerate to death the stories of our city vacations with our biological families. (We traveled with our mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. For a week, we were a city family, dressed in the fancy travel clothes that were handed down from one child to another for traveling to the city.) When we came back, each one separately, from the kibbutz apartment on Sheinkin Street in Tel Aviv, we told each other about the same Medrano Circus we all went to. Except that the night we were at the circus with our biological family was different from the other nights—that night, the lions escaped from their cage, the tightrope walker fell off the rope—that’s what we said. We told each other stories that were totally unrelated to reality.

Sometimes, after we’d left the kibbutz, we tried to tell our story to city people. We weren’t able to get it across, neither the plot nor the tone. Our voices grated like the off-key recorder playing of our childhood, too high or too low. We gave up in the middle. The words fell, hollow, between us and the city people the way the stitches fell from our mothers’ knitting needles as they sat silently beside their talking husbands during the Saturday night kibbutz meetings.

We spoke in the plural. That’s how we were born, that’s how we grew up, forever. Our horizons were strange, bent.

From the moment we were released from the hospital, they never tried to separate us. On the contrary, they joined us, glued us, welded us together.

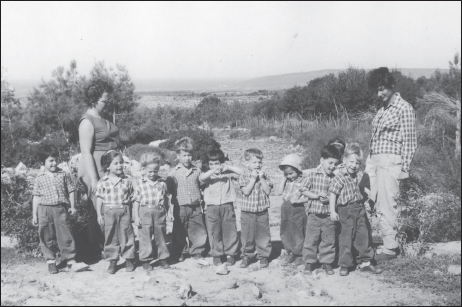

The Narcissus children in the nursery; Yael is pictured first from the left.

But that being welded together wasn’t the main thing, even if people who talk about their childhood on the kibbutz sometimes think it is. It was merely a byproduct of the experiment with socialism. (The decision regarding communal sleeping arrangements was taken in 1918 and applied to all the kibbutzim, except for some of the older ones—Degania Aleph, Degania Bet and Ein Harod—who opposed it. They were exempt. Degania was there first, even before the system and the regulations.)

Their intention wasn’t to weld, but just the opposite, to separate; to separate the children from the oppressive weight of their parents, who would pamper them and impose their wills on them with mother’s milk and father’s ambitions. To separate and protect the children from the bourgeois nature of the family. “We will change henceforth the old tradition,” as the Internationale proclaimed, and a different, more just and egalitarian world would rise, like a phoenix, from its ashes. That was their declared intention and hope—that the new child would grow into a new kind of person. The longing of some of the kibbutz children for the family they never had was the longing for an idea we had no inkling of, like, for instance, the longing of the Jews in the Diaspora for Jerusalem.

I was in the second grade when I saw an adult wearing pajamas for the first time. It was my father, who had fallen asleep during the afternoon shift. We went to our parents’ rooms every day from 5:30 to 7:20 in the evening, a total of one hour and fifty minutes (until the seventh grade, when they sent us away to an educational institution in Evron). At 5:30 that day I went into their room without knocking (we didn’t knock on any doors, and ours were always open twenty-four hours a day—after all, there was nothing to hide; the houses belonged to all of us, they weren’t a bourgeois possession to be guarded and fortified), and he was asleep in bed wearing pajamas. I ran outside, my pulse racing, and yelled that my father was dead. He’s dead. Someone saw me on the sidewalk and, concerned, went inside to check. Zvi N. is not dead, Zvi is sleeping. That’s how grown-ups look when they’re sleeping: they lie quietly on their beds, their faces to the wall, their backs to us, wearing enormous pajamas and covered with a piqué blanket.

Our story appeared to be only a plot, a plot that was the system, which suited neither children nor adults. Our parents lived alongside it and we lived under it. No one actually lived inside it because it was not meant to house people, only their ambitions and dreams. But we and our parents tried with all our hearts to live inside it; that was the experiment. Our system couldn’t be satisfied. We were in awe of it, and we knew that we would never totally succeed. We worshipped it day and night, the older generation (our parents) in the hundreds of vacation days they accumulated, the fruit of their endless labors. And we in the fields, in the dining room, in the children’s house. Everywhere.

We knew nothing about the grown-ups’ lives, neither about their waking hours nor about their sleep. They inhabited a different planet from ours.

We moved in front of each other like two rows of dancers who grew closer and farther apart from each other in the measured steps of the Friday night dances held in the dining room. We with our flowery group names: Narcissus, Anemone, Squill. They with their group names, which represented the fulfillment of their ideals: The First of May, Stalin, Meadow, Workers. We with our first names, fresh with dew and raindrops: Yael, Michal, Tamar, Ronen. They with their names recently Hebraicized from the Hungarian: from Freddie to Zvi, Aggie to Naomi, Latsi to Itzhak.

We existed in parallel universes—we lived with the Children’s Society, our parents with the grown-ups.

We moved in large masses, like a flock of birds, like a herd of zebras, always in two large groups. All the children went together to their daily 5:30 visits, walking each other to their biological parents’ houses, and one hour and fifty minutes later, at 7:20, we walked back along the same paths with our parents, who returned us to the children’s houses.

We ate our supper in the children’s house. They ate theirs in the dining room.

Even before then, right after we were born, we were sent straight from the hospital to the babies’ house, to the metapelet1 who was waiting there for the mothers. They used to come to nurse together, sitting one next to the other, always at the same time. The synchronization was meant to guarantee that no child got more. Not less and not more. The parents arrived in flocks at bedtime too, for the quarter of an hour they were allowed. Not all of them came, because bedtime was the same in all the children’s houses, and apart from that, many of them were busy building the kibbutz, sitting on committees. We moved before them with wheat sheaves in our hands on Rosh Hashanah, we acted out the Hadgadya song on Passover, threading our way among the long tables to the stage in our festive clothes. We came together in the well-orchestrated choreography, unknowingly following the instructions in the loose-leaf binders of detailed plans for celebrating the holidays that were sent to all Hashomer Hatzair2 kibbutzim and then adapted by the Holiday Committee to suit its particular kibbutz. We made fleeting incursions into their nightlives on holidays and left “with timbres and with dances […] the horse and his rider hath He thrown into the sea,” in the unique steps created for us by Nira. (All kibbutz children were doing the same thing at exactly the same time, celebrating the Hashomer Hatzair Pessach Haggadah.) We danced before them on the lawn, at end-of-year school shows, and on the kibbutz holiday we sang, “We’re building a kibbutz of beauty, the likes of which you never did see, the likes of which you never did see.”

The Narcissus children at the beach; Yael is pictured second from the left.

They, the adults, sang too. They sang in harmony in a choir, danced the Chassidic dances that were danced at weddings on all Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim, without a rabbi. (The couples went to the Rabbinate in Nahariya, got formally married and came back for the parties so that the rabbi wouldn’t set foot on the kibbutz, so that their religion wouldn’t touch our religion.)

Four couples get married. The grown-ups dance and we stand there with wreaths on our heads, large branches forming a gate for the pairs of chosen children, and we sing Kadya Molodovski, the city woman whose words accompanied our lives, like a melody: “Open the gate, open it wide, like a golden chain, we’ll go inside: father and mother, sister and brother, groom and bride, in a chariot we all will ride.”

We sang, we danced, we played the recorder, the mandolin and the cymbals, and when the artistic program was over, we all went back to our places. The lawn emptied out, the door to the dining room closed behind us, and we returned to our little world in the Narcissus house with its little bathrooms, its little beds, its little tables, surrounded by the Children’s Society—Anemone under us and Terebinth above us. We were happy.

At night we dreamt about the heroes of Eric Kästner’s stories that our metapelet read to us from nine until nine twenty every evening, sitting in the corridor, only her voice audible, we in our beds. Noriko-san, the little girl from Japan, was exactly our age.

Sometimes our dreams were chaotic. Scary stories we were told remained hanging above us like a black cloud. The metapelet said goodnight and left, closing the door behind her, and we were awake. Frightened. As if the Red Everlasting flower pin that we loved with every ounce of our being had penetrated the white shirts we wore on holidays, piercing our skin. And we waited for the light to come so we could run outside. We were always allowed to escape from classes, as in enlightened countries where prisoners who escape are not tried because it is the nature of man to try to escape from prison, to be free. In the middle of our lessons, we sailed on boards in our reservoir pond. Sometimes we got up at night, sat at the doors to our rooms and spoke or played. We couldn’t fall asleep. Once, we lit a bonfire in our dining room and went back to our beds. There were no grownups in our world at night.

Actually, the story of our creation, the creation of the new world, never happened. Maybe that was why we told it to ourselves over and over again. We didn’t have a written language or one that we could use to translate our lives for the city people.

We thought that multitudes would join us. Groups from Hashomer Hatzair, volunteers from overseas, workers of the world. We didn’t know that, in 1960, we were born to a star whose light had long since died and it was now on its way to the sea. We didn’t know that the kibbutz movement had been at the height of its prestige during the Wall-and-Tower period in the 1930s, and that before the establishment of the state in 1947, the kibbutz population was the highest it would ever be—7% of the entire Jewish population. In ’48, we were already decreasing, and in the ’70s, we were only 3.3% of the entire population.

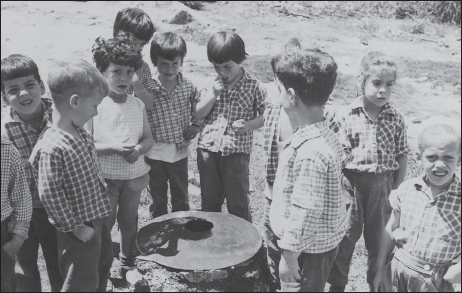

The Narcissus group on an excursion;

Yael pictured fifth from right, the smallest child wearing the hat.

We didn’t know that our star illuminated only itself. We thought that we were growing and building.

We were born in 1960 on Kibbutz Yehiam, the most beautiful kibbutz in the world—green with pines, purple with Judas trees, yellow with broom plants—founded in 1946 on a hill below a Crusader fortress. We were born to the Narcissus Group. We were sixteen children in Narcissus, eight boys and eight girls. We were a gentle group, most of us born to older parents, the Hungarian founders of the kibbutz who built it together with an Israeli group of Hashomer Hatzair.

We said the names of the children in our group quickly, all strung together, in order of age. There was also the alphabetical order of surnames, the bourgeois order that could only be used by strangers who didn’t know anything, or by doctors, when, for instance, we were waiting our turn to see the dentist who came from Nahariya or the Krayot near Haifa. In an indifferent tone, he used to dictate to Miriam Ron, who was in charge of the clinic, the bad news that was repeated every year: seven cavities, or nine, or twelve. We had so many cavities and so few sweets. And we all wore braces made for us by the orthodontist. We also waited on line for him until Miriam called us in the alphabetical order of our surnames, and he too came from Nahariya or the Krayot.

We hadn’t exactly chosen the name Narcissus, even though we did ultimately vote for it, unanimously, in the first grade. The group’s name went with us everywhere—it hung on the bulletin board and was written on the name tag sewed onto our clothes in the communa, the clothing supply room. Every group had its own color and its own Roman numeral. We were brown and our number was X.

When we chose the name, we still weren’t familiar with the rules. We didn’t understand that we had to have the names of flowers or something else in nature. When we were born, there were already about 120 children on the kibbutz, divided into groups by age. And although the groups before us were called Rock, Grove, Cyclamen, Pomegranate, Pine, Oak and Terebinth, we still didn’t understand. We never noticed.

We suggested a variety of names, most of them ending with “Gang.” “The Explosion Gang,” “The Forest Gang,” and all the other adventurous sounding names. The metapelet directed us, at first gently, then more firmly to the world of flowers until we fell into line and chose Narcissus. I don’t remember the name of the other flower we were considering; I think we already realized that it didn’t matter if we were Narcissus, Anemone or Chrysanthemum—the names given to the groups that came after us. We understood that it was like choosing white or carrot-orange sandals that had the same shape.

Other kibbutzim like ours throughout the country, from the Galilee to the Negev, chose the same names. And we all dreamed about Noriko-san, the little girl from Japan.

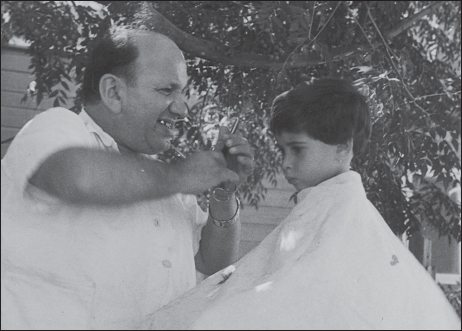

Fishel from Nahariya was the kibbutz barber.

Every once in a while, at intervals that we could not understand, he would come to us, the Narcissus Group. Amongst ourselves, we called him Dr. Fishel, maybe because of Dr. Zuriel, the kibbutz doctor, who also came from Nahariya, and Dr. Pollack, his replacement who also came from Nahariya, and Dr. Lieber, the dentist. We thought that maybe everyone in Nahariya was a doctor. But Fishel wasn’t a doctor; nor was he one of the Naharyia Yekkim, the Jews of German descent who lived in that city. He was Fishel the Barber, and he lived in the transit camp next to the Nahariya hospital.

Fishel, the kibbutz barber, at work.

We hated having our hair cut, but we suffered mainly from Fishel’s lies. It never occurred to us that you could lie without blinking an eye and even repeat the same lies over and over again. We sat in regular chairs for our haircuts. There were no adults around and we really didn’t understand the order in which we were called. Whenever it was another child’s turn, the sheet was flapped around his shoulders like a bib, quickly, and there wasn’t a lot of time to be afraid. It was clear that after he left us, Fishel moved on with his equipment to cut other children’s hair. Only much later did we learn, almost by chance, that all the professionals—the barbers, doctors, dentists—worked not only with the children, but with all the kibbutz members. They came, worked for a flat rate, and left.

As he worked, Fishel asked each child what he wanted: Balloons? Candy? Then he memorized each answer (or so we thought) and promised to bring balloons or candy on his next visit. That’s how it was every time. And he never brought anything. But we believed him each time and cried with disappointment when no gifts arrived the next time either. Fishel, after all, came from Nahariya, a city that was all candy and chocolate-coated bananas in the stores and rolls and butter in Hans and Gila’s café. Enchanting coaches drawn by horses rolled along Haga’aton Boulevard, whisking passengers from one place to another. All the best things in the world were there, and he probably never gave us a thought as he walked past all the display windows.

But Fishel must have hated us much more than we hated him, and he certainly didn’t have the money to buy us presents. We didn’t even know whether he had children of his own. We didn’t know a thing about the homes of our dentists in Haifa and the Krayot; we thought that all the city people were rich. We didn’t know that they worked at a flat rate and lived in transit camps.

We drowned in a sea of our own sweat. The sounds of the recorders, mandolins and cymbals deafened us. We were burned by the banner of letters that were doused in kerosene and set aflame: “For Zionism, Socialism and the Brotherhood Amongst Nations,” like the slogan of the newspaper Al Hamishmar that was put in our parents’ mailboxes everyday. But we never connected that to our neighbors in Yanuh, the Druze village visible at the edge of the horizon on the eastern side of the fortress. We used to go hiking there with our teacher, crossing our wadi, the Yehiam stream, hearing about the arbutus and Judas trees, and, in a demonstration of the brotherhood amongst nations, walked up to Yanuh’s enormous school for a visit. There, they always gave us brightly-colored candy and invited us to see their classes. We reciprocated by inviting them to visit us. When they came, we gave them wafers. We played soccer. We beat them by so much, 13:1 or 12:0, that we were dizzy with victory for days.

We didn’t know that thousands of people lived in Yanuh, that the town had no infrastructure, that they had to study Bialik, the Hebrew poet. They told us, but we didn’t study Bialik, so we didn’t understand what that meant. We knew nothing. Neither Hebrew nor Arabic. Yanuh was two kilometers away, but light-years separated us.

And we knew nothing about our neighbors in the development town of Ma’alot, except that, starting in the seventh grade, we had to help them with their homework once a week for two hours. We knew nothing about Lebanon on the other side of the border.

We knew nothing about Kabri either, the kibbutz we had to pass on the way to see the doctors in the Kupat Holim clinic in Nahariya. Because Kabri wasn’t in Hashomer Hatzair.

We walked around like fakirs,3 both children and adults, on the surface of a moon nobody wanted to discover. We believed that we would pluck stars and the stars, like fireworks, would light up the skies over all the countries in the world. And workers would march by their light as if they were torches, and equality and justice would descend upon the world. Our legs hurt so much from the effort that we could focus only on the march itself. We forgot who we were bringing equality to, who we were forging peace with and who deserved justice. We drank our sweat and helped no one.

Volunteers used to come to us from all over the world. They came on their school vacations, filled with enthusiasm about what was called “lending a hand,” helping us with our work. We played volleyball with them, spoke our broken English, played guitars, tried lying on a waterbed. Look, the world is coming to us, so blond, fair and polite. They worked, took an interest in our lives and then went back overseas. We went on with our lives.

The old-timers and adults that we, the children, considered important were, in certain cases, totally different from the ones immortalized in the kibbutz’s official history, in The Jubilee Book or various other commemorative projects. We already knew when we were children that on our kibbutz, Yehiam, and on all the kibbutzim from the Sea of Galilee to the Negev, there was always a rotation in the higher, desirable positions, such as secretary, work coordinator, and the like.

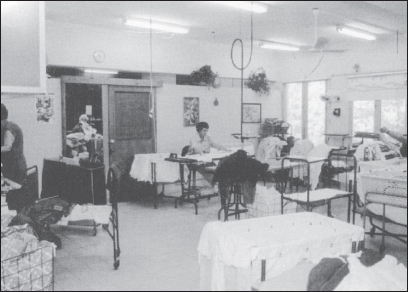

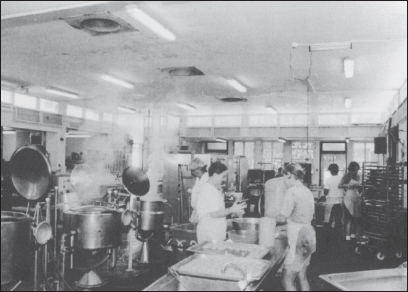

We didn’t notice, neither then nor later on, that there was no rotation in other occupations. No one ever asked to switch jobs with the women who did the laundry; no one ever coveted the Sisyphean work of the potato peelers, who spent decades sitting on low stools beside huge pots in the kitchen. There was never any rotation for the woman who cleaned the public showers and toilets for years. On the kibbutzim, those jobs were designated the “service branch” (to differentiate them from the profitable and productive jobs in the fields or factories), like an HQ battalion whose soldiers remain in camp to outfit tanks and prepare food for the hungry officers and troops returning from maneuvers or the battlefield.

Women working in the communa, the clothing storeroom.

Women working in the kitchen.

Rotation, one of the marvels of our system, protected the prominent members who moved from one major function to another, and turned its back on the members of the lower castes, keeping them trapped in place.

Most of the service providers were from the Workers group. The name hadn’t been chosen deliberately to be such a dazzlingly ironic contrast to the First of May group, whose members were among the founders of the kibbutz and members of the movement even before the war, in Hungary.

The members of the Workers group were Zionist refugees of the war who joined Hashomer Hatzair in Hungary after the war, and immigrated to Israel under the movement’s sponsorship. They said later: “To this day, it is not clear what had more of an effect on us: the ideological arguments or the good chocolates and cigarettes.” They arrived in Yehiam two years after it had been established, several months after the War of Independence battles that had been fought there. They were full partners in the building and development of the kibbutz.

Even after we, members of the kibbutz, left, and even after the volunteers and many members of all the other groups were gone, members of the Workers group remained. The largest percentage of those who remained in Kibbutz Yehiam at any time was from the Hungarian Workers group.

Our contact with the grown-ups was dictated by the logic of our everyday lives and included only those who played a part in them: teachers, metaplot,4 workers in the communa (the clothing storeroom), the shoe repair workshop and the dining hall—people from the service branch.

The heroes of our mythology were almost all members of the Workers group because they were the ones who worked on the kibbutz land, in the communa, in the kitchen. They were the ones who sometimes stopped beside us on the sidewalk and gave us an affectionate pat. And they were also the only ones who allowed their children to stay in their biological homes for a while after they ran away from the children’s house, and gave them candy. We didn’t know then that they were from the Workers group, and neither my brothers nor I knew that our mother was from the First of May group and that our father had come to the country earlier, in 1939, after a family council convened in Vienna and decided that all the young people would leave without delay.

After all, the past is irrelevant on kibbutzim. Everyone—whether born in a village in Hungary or in Budapest, in Vienna or Haifa—is equal in the eyes of the system.

The head of the Hungarian old-timers in the Workers group, the leader of all the old-timers, the person in first place, miles ahead of everyone else, was Pirosh. Though he did not take part in the battles with the Arabs in the War of Independence (members of the Workers group arrived in Yehiam after that war), or establish an agricultural branch, and was never appointed kibbutz secretary or work coordinator, we knew that without him, the kibbutz would collapse.

Twice a year, a line of our children, like a huge centipede, would go to the shoemaking workshop and try on the new shoes that Pirosh made for us.

Pirosh means “red” or “redhead” in Hungarian, but when we were born, he was already more bald than redheaded. Pirosh cursed whenever he wanted, gave our thighs a hard, painful slap whenever he wanted, and chose his helpers in the colbo, where we got supplies, from among the girls in the seventh grade or higher, based on the size of their breasts. He said it as if he were talking about awarding medals to the girls he described as having “large balconies.” No one on the kibbutz ever spoke like that, only Pirosh. He was the shoemaker, he chose the movies we saw and screened them, and he was in charge of the weapons storeroom and the colbo. Each of those was almost a full-time job.

The shoemaking workshop was a small shed on the edge of the kibbutz, whose walls, and especially its high, slanted ceiling, were covered with pictures of starlets—that’s what Pirosh called them—that he clipped from various magazines. All of them were glamorous women with plunging necklines, huge breasts and broad smiles. Pirosh taught us their names. We didn’t know whether that shed was really so different from other kibbutz buildings, or whether it seemed so different to us because of the starlets, the smell of leather and the shoe-stretching machines. The workshop consisted of two rooms, and Pirosh sat in the first room with his constant assistant, Meir S., an excellent professional shoemaker, who people said had also been one in Hungary. Meir S. would stop working only to smile his bashful smile and ask how we were, and he was never irritable. They sat on either side of a huge worktable that was littered with tools and shoe parts.

They worked with their entire bodies, and their mouths were always full of nails, as were all their pockets.

The other room contained the stretching machines, many boxes of shoes, and two small stools on which we would sit in front of Pirosh to try on the new line he made for us twice every year—high shoes in winter and sandals in summer. We came to choose a color: sandals in white or carrot-orange for girls, and brown for boys; shoes in red or brown for all of us. The shape was the same for all the children of the Kibbutz Artzi movement.

No one knew exactly what Pirosh’s story was. He was such a presence that questions seemed unnecessary. But we asked anyway. Pirosh was single. Sometimes our centipede, shod in red or brown, would stop near a group of old-timers and ask why Pirosh was single, why he didn’t have any children. They didn’t answer us. It was as if our question passed, like a paper plane, over the heads of those busy people rushing from place to place, without ever landing. He was single, and that was that. Once, someone told us that it was a case of unrequited love. We considered every aspect of that answer, but couldn’t remember who said it and whether he really meant it. Maybe he just wanted to get rid of us. Non-practical matters were never discussed. Nor were Pirosh’s hard, painful slaps of our thighs when he measured our new shoes and explained: “I’m measuring you thoroughly.” We laughed at his jokes, collected them and repeated them over and over again.

The Narcissus group preparing bread in the backyard.

Pirosh pronounced all the names of Hollywood actors and actresses with a Hungarian accent, and we thought that not only did he know their names, but he actually knew them. The pictures that lined the walls of the shoemaking workshop revealed to us the cleavage of Raquel Welch and company, and in that décolletage, we saw an escape, a hint that a different kind of life was possible. The idea of hanging pictures of women with their cleavage exposed was so out of the ordinary that Hashomer Hatzair did not have a clause in its rules of conduct prohibiting it. And that’s another reason we were so proud of Pirosh. In our heart of hearts, we knew that he worked an additional job for us that was much more important than all the other services he provided: For us, he symbolized the existence of other worlds—L’Hiton (an entertainment magazine), Tel Aviv, Hollywood and New York. As if he were actually a subversive one-man international commune, a clever one never seen as dangerous because it never had to declare itself. That’s why no one noticed how much Pirosh’s existence and his pictures seeped into our minds.

Pirosh’s various occupations allowed him to travel a great deal, though never at the expense of work, as he always pointed out. He merely took advantage of the hundreds of vacation days the old-timers had accumulated, the fruit of their endless labors. He went to Tel Aviv, where he saw dozens of movies. Then he brought them to us from the Movie Department.

Until the end of the sixth grade, we saw the movies with the Children’s Society. Apart from his job of choosing and screening the movies, Pirosh was also in charge of censoring them. There were no parents, metaplot or teachers at the screenings. Only we and Pirosh were there, like in the shoemaking workshop.

Every other week, he brought a movie from Tel Aviv: Annie Get Your Gun, Lassie Come Home, Winnetou, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. He didn’t censor vulgarities, only frightening scenes. When a scene he considered frightening was about to appear on the screen, Pirosh would simply order all the children in the third grade and below to leave. That’s why we never saw the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz. Suddenly he turned on the lights and sent us out.

When we were in the seventh grade, we joined the adults on movie night, which the entire kibbutz eagerly awaited. Once a week we’d sit in rows in the large dining hall. The screening would be delayed, the way daily lectures and Friday night dinners in the dining hall were delayed, until everyone agreed on whether to open or close the windows. Those arguments were like a silent movie being shown over and over again before the main feature. First the window-closers would get up, and without a word, close them and sit down. Then the window-openers would get up, open them and sit down. The two groups operated in a sequence known only to them.

No one ever intervened, neither the children nor the adults. We all knew that this had also come from there. (Most of the Hungarians, from both The First of May and the Workers groups, came from there. And there—my mother told me once when I was sick—the Danube froze over in winter. And there—another member once told us—the Danube was red with blood because so many Jews had been shot and thrown into it all at once.) Somehow, we all accepted the explanation of the getting-up-and-opening and the getting-up-and-closing offered by one kid in our centipede to another: Anyone who was in the camps or holed up in a cramped hiding place needed to open. Anyone who was in an open area or who was set upon by dogs had to close. We would wait. For those who closed and those who opened.

After the windows issue was resolved, Pirosh would begin the screening, the first reel threaded and ready to go. Carmi, one of his constant apprentices, son of Meir S. from the shoemaking workshop and the only person Pirosh trusted, would help him. Pirosh had begun training him for the job when he was seven.