COLLECTED WORKS VOLUME 6

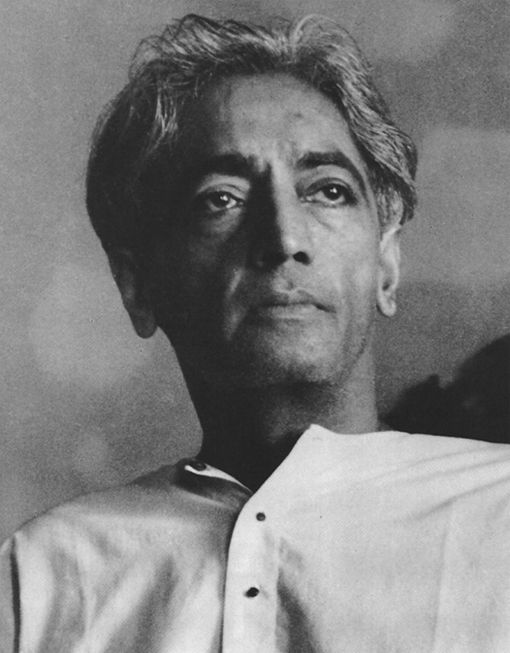

Photo: J. Krishnamurti ca 1948 by D. R. D. Wadia

Copyright © 2012 by Krishnamurti Foundation America

P.O Box 1560, Ojai, CA 93024

Website: www.kfa.org

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 13: 9781934989395

ISBN: 1934989398

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62112-688-1

Contents

Preface

Talks in Rajahmundry, India

First Talk, November 20, 1949

Second Talk, November 27, 1949

Third Talk, December 4, 1949

Talks in Madras, India

First Talk, December 18, 1949

Second Talk, January 29, 1950

Third Talk, February 5, 1950

Talks in Colombo, Ceylon

First Talk, December 25, 1949

Action, Radio Talk, December 28, 1949

Second Talk, January 1, 1950

Third Talk, January 8, 1950

Fourth Talk, January 15, 1950

Fifth Talk, January 22, 1950

Relationship, Radio Talk, January 22, 1950

Talks in Bombay, India

First Talk, February 12, 1950

Second Talk, February 19, 1950

Third Talk, February 26, 1950

Fourth Talk, March 5, 1950

Fifth Talk, March 12, 1950

Sixth Talk, March 14, 1950

Talks in Paris, France

First Talk, April 9, 1950

Second Talk, April 16, 1950

Third Talk, April 23, 1950

Fourth Talk, April 30, 1950

Fifth Talk, May 7, 1950

Talks in New York City, New York

First Talk, June 4, 1950

Second Talk, June 11, 1950

Third Talk, June 18, 1950

Fourth Talk, June 25, 1950

Fifth Talk, July 2, 1950

Talks in Seattle, Washington

First Talk, July 16, 1950

Second Talk, July 23, 1950

Third Talk, July 30, 1950

Fourth Talk, August 6, 1950

Fifth Talk, August 13, 1950

Talks in Madras, India

First Talk, January 5, 1952

Second Talk, January 6, 1952

Third Talk, January 12, 1952

Fourth Talk, January 13, 1952

Fifth Talk, January 19, 1952

Sixth Talk, January 20, 1952

Seventh Talk, January 26, 1952

Eighth Talk, January 27, 1952

Ninth Talk, February 2, 1952

Tenth Talk, February 3, 1952

Eleventh Talk, February 9, 1952

Twelfth Talk, February 10, 1952

Talks in London, England

First Talk, April 7, 1952

Second Talk, April 8, 1952

Third Talk, April 15, 1952

Fourth Talk, April 16, 1952

Fifth Talk, April 23, 1952

Sixth Talk, April 24, 1952

Questions

Preface

Jiddu Krishnamurti was born in 1895 of Brahmin parents in south India. At the age of fourteen he was proclaimed the coming World Teacher by Annie Besant, then president of the Theosophical Society, an international organization that emphasized the unity of world religions. Mrs. Besant adopted the boy and took him to England, where he was educated and prepared for his coming role. In 1911 a new worldwide organization was formed with Krishnamurti as its head, solely to prepare its members for his advent as World Teacher. In 1929, after many years of questioning himself and the destiny imposed upon him, Krishnamurti disbanded this organization, saying:

Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path. My only concern is to set men absolutely, unconditionally free.

Until the end of his life at the age of ninety, Krishnamurti traveled the world speaking as a private person. The rejection of all spiritual and psychological authority, including his own, is a fundamental theme. A major concern is the social structure and how it conditions the individual. The emphasis in his talks and writings is on the psychological barriers that prevent clarity of perception. In the mirror of relationship, each of us can come to understand the content of his own consciousness, which is common to all humanity. We can do this, not analytically, but directly in a manner Krishnamurti describes at length. In observing this content we discover within ourselves the division of the observer and what is observed. He points out that this division, which prevents direct perception, is the root of human conflict.

His central vision did not waver after 1929, but Krishnamurti strove for the rest of his life to make his language even more simple and clear. There is a development in his exposition. From year to year he used new terms and new approaches to his subject, with different nuances.

Because his subject is all-embracing, the Collected Works are of compelling interest. Within his talks in any one year, Krishnamurti was not able to cover the whole range of his vision, but broad amplifications of particular themes are found throughout these volumes. In them he lays the foundations of many of the concepts he used in later years.

The Collected Works contain Krishnamurti’s previously published talks, discussions, answers to specific questions, and writings for the years 1933 through 1967. They are an authentic record of his teachings, taken from transcripts of verbatim shorthand reports and tape recordings.

The Krishnamurti Foundation of America, a California charitable trust, has among its purposes the publication and distribution of Krishnamurti books, videocassettes, films and tape recordings. The production of the Collected Works is one of these activities.

Rajahmundry, India, 1949

First Talk in Rajahmundry

There is an art in listening. Listen to find out if what is said is of significance, and after listening, judge, accept, or throw out—but first of all listen. The difficulty with most of us is that we do not listen. We come prepared to be antagonistic or friendly, and not to listen neutrally. If you listen neutrally, surely then only do you begin to discover what lies behind the words. Words are a means of communication. You have to learn my vocabulary, the meaning behind my words, and then you will find the significance of the subject. The thing of first importance is to learn to listen rightly. If you read a poem and are biased, how can you understand it? To appreciate what the poet wants you to understand, you must come with freedom to do so.

The problem that confronts most of us at this juncture is whether the individual is merely the instrument of society or the end of society. Are you and I as individuals to be used, directed, educated, controlled, shaped to a certain pattern by society, government; or does society, the state, exist for the individual? Is the individual the end of society, or is he merely a puppet to be taught, exploited, butchered as an instrument of war? That is the problem that is confronting most of us. That is the problem of the world: whether the individual is a mere instrument of society, a plaything of influences to be molded, or whether society exists for the individual.

How are you going to find this out? It is a serious problem, isn’t it? If the individual is merely an instrument of society, then society is much more important than the individual. If that is true, then we must give up individuality and work for society; then our whole educational system must be entirely revolutionized and the individual turned into an instrument to be used and destroyed, liquidated, got rid of. But if society exists for the individual, then the function of society is not to make him conform to any pattern, but to give him the feel, the urge of freedom. So we have to find out which is false.

How would you inquire into this problem? It is a vital problem, isn’t it? It is not dependent on any ideology, either of the left or of the right; and if it is dependent on an ideology, then it is merely a matter of opinion. Ideas always breed enmity, confusion, conflict. If you depend on books of the left or of the right, or on sacred books, then you depend on mere opinion, whether of Buddha, of Christ, of capitalism, communism, or what you will. They are ideas, not truth. A fact can never be denied. Opinion about fact can be denied. If we can discover what the truth of the matter is, we shall be able to act independently of opinion. Is it not, therefore, necessary to discard what others have said? The opinion of the leftist or other leaders is the outcome of their conditioning. So if you depend for your discovery on what is found in books, you are merely bound by opinion. It is not a matter of knowledge.

How is one to discover the truth of this? On that we will act. To find the truth of this, there must be freedom from all propaganda, which means you are capable of looking at the problem independently of opinion. The whole task of education is to awaken the individual. To see the truth of this, you will have to be very clear, which means you cannot depend on a leader. When you choose a leader you do so out of confusion, and so your leaders are also confused, and that is what is happening in the world. Therefore you cannot look to your leader for guidance or help.

The problem, then, is how to find the truth of this matter: whether the individual is the instrument of society or whether society exists for the individual. How are you going to find this out—not intellectually, but factually? What do you mean by the individual? What is the ‘you’? What are we, physically and psychologically, outwardly and inwardly? Are we not the result of environmental influences? Are we not the result of our culture, nationality, religion, and so on? So the individual is the result of education, technical or classical. You are the result of environment. There are those who say that you are not only physical but something more—in you is reality, God. This, after all, is but an opinion, the result of the influence of society. It is a conditioned response, nothing more. Here in India, you believe you are more than the outcome of material influences. Others believe they are nothing more than that. Both beliefs are conditioned. Both are the result of social, economic, and other influences—which is fairly obvious. Therefore we have first to recognize that we are the result of the social influences about us. Whether you believe in Hinduism, Christianity, the leftist ideology, or in nothing at all, you are the result of that conditioning.

Now, to find out if you are something more, there must be freedom from conditioning. To be free, you must question the whole social response, and only then can you find out whether the individual is merely the result of society or something more. That is, you can find out the truth of this only through questioning the social, economic, environmental influence, the ideologies, and so on. Only those who question are capable of creating social revolution. Such individuals, being free of patterns, beliefs, ideologies, are able to help to create a new society which is not based on any conditioning.

So, seeing that the world at the present time is in conflict, with imperialism, wars, starvation, increase in population, unemployment, antagonism—seeing all this, the person who is really serious has to find out whether the individual is the end of society, that is, whether society exists for the individual. If it does, then the relationship between the individual and society is entirely different. Then the individual is a free being in relation to society, which is also free. This requires an enormous understanding of oneself. Without self-knowledge, there is no basis for thinking; you are merely shaped by the winds of circumstance. Without knowing the total self, there can be no right thinking. The understanding of oneself is not to be found in withdrawal from life, in running away from society to the woods; on the contrary, it is to be found in relationship with one’s wife, with one’s son, with society. Relationship is a mirror in which you see yourself, but you cannot see yourself as you are if you condemn what you see. After all, if you want to understand someone, you do not condemn him, but study, observe him under all conditions. You are a silent watcher observing, not condemning—and then only do you understand. Out of that understanding comes clarity, which is the basis of right thinking. But by the mere repetition of ideas, however wonderful they may be, we become gramophones playing according to various influences, but still gramophones. It is only when we cease to be gramophones that the individual acquires significance. We are then true revolutionaries because we discover the real. Freedom from ideas, from conditioning, can alone bring revolution—which must begin with you, not with a blueprint. Any clever person can draw up a blueprint, but it is useless. To discover what one is brings about a radical revolution, and that discovery does not depend on a blueprint. Such a discovery is essential to bring about a new state.

I have been handed several questions. Before I answer them, it is important to find out why you ask questions. Is it to strengthen your opinions or to create a controversy or to deny what is said? Because, if you cling to your views, you will listen with your arguments; you will not listen to find out what is being said. I hope you will listen, not in the spirit of antagonism, but to find out what the truth is. If you meet what is being said with your opinions, of what value is it to listen?

Question: In your talks, you say that man is the measure of the world and that when he transforms himself, the world will be at peace. Has your own transformation shown this to be true?

KRISHNAMURTI: What is implied in this question? That though I say I recognize that I am the world, and the world is not separate from me, though I talk against wars and so on, exploitation still goes on, so what I say is futile. Let us examine this. You and the world are not two different entities. You are the world, not as an ideal, but factually. You are the result of climate, of nationality, of various forms of conditioning, and what you think, what you feel, that you project—and you create a world of division. You want to be Telugus against Tamils, God knows why. What you project is the world; you create the world. If you are greedy, that you project—so the world is yourself. As the world is yourself, to transform the world you must know yourself. In the transformation of yourself, you produce a transformation in society. The questioner implies that since there is no cessation of exploitation, what I am saying is futile. Is that true? I am going around the world trying to point out truth, not doing propaganda. Propaganda is a lie. You can propagate an idea, but you cannot propagate truth. I go around pointing out truth, and it is for you to recognize it or not. One man cannot change the world, but you and I can change the world together. This is not a political lecture. You and I have to find out what is truth, for it is truth that dissolves the sorrows, the miseries of the world. The world is not far away in Russia or America or England. The world is where you are, however small it may seem; it is you, your environment, your family, your neighbor, and if that is transformed, you bring transformation in the world. But most of us are lazy, sluggish. What I say is real in itself, but it is futile if you are unwilling to understand it. Transformation can be brought about only by the individual. Great things are performed by individuals, and you can bring about a phenomenal, radical revolution when you understand yourselves. Have you not noticed in history that it is individuals who transform, not the mass? The mass may be influenced, used, but the radical revolutions in life take place with individuals only. Wherever you live, at whatever level of society you may be placed, if you understand yourselves you will bring about transformation in your relationship with others. What is important is to put an end to sorrow, for the ending of sorrow is the beginning of revolution, and that revolution brings about transformation in the world.

Question: You say that gurus are unnecessary, but how can I find truth without the wise help and guidance which only a guru can give?

KRISHNAMURTI: The question is whether a guru is necessary or not. Can truth be found through another? Some say it can, and some say it cannot. As this is a question of importance, I hope you will pay sufficient attention. We want to know the truth of this, not my opinion as against the opinion of another. I have no opinion in this matter. Either it is so, or it is not. Whether it is essential that you should or should not have a guru is not a question of opinion. The truth of the matter is not dependent on opinion, however profound, erudite, popular, universal. The truth of the matter is to be found out in fact.

First of all, why do we want a guru? We say we need a guru because we are confused and the guru is helpful—he will point out what truth is, he will help us to understand, he knows much more about life than we do, he will act as a father, as a teacher to instruct us in life, he has vast experience and we have but little, he will help us through his greater experience, and so on and on. That is, basically, you go to a teacher because you are confused. If you were clear, you would not go near a guru. Obviously, if you were profoundly happy, if there were no problems, if you understood life completely, you would not go to any guru. I hope you see the significance of this. Because you are confused, you seek out a teacher. You go to him to give you a way of life, to clarify your own confusion, to find truth. You choose your guru because you are confused, and you hope he will give you what you ask. That is, you choose a guru who will satisfy your demand; you choose according to the gratification he will give you, and your choice is dependent on your gratification. You do not choose a guru who says, “Depend on yourself”; you choose him according to your prejudices. So, since you choose your guru according to the gratification he gives you, you are not seeking truth but a way out of confusion, and the way out of confusion is mistakenly called truth.

Let us examine first this idea that a guru can clear up our confusion. Can anyone clear up our confusion?—confusion being the product of our responses. We have created it. Do you think someone else has created it—this misery, this battle at all levels of existence, within and without? It is the result of our own lack of knowledge of ourselves. It is because we do not understand ourselves, our conflicts, our responses, our miseries, that we go to a guru who we think will help us to be free of that confusion. We can understand ourselves only in relationship to the present, and that relationship itself is the guru, not someone outside. If I do not understand that relationship, whatever a guru may say is useless because if I do not understand relationship, my relationship to property, to people, to ideas, who can resolve the conflict within me? To resolve that conflict, I must understand it myself, which means I must be aware of myself in relationship. To be aware, no guru is necessary. If I do not know myself, of what use is a guru? As a political leader is chosen by those who are in confusion and whose choice therefore is also confused, so I choose a guru. I can choose him only according to my confusion; hence he, like the political leader, is confused.

So, what is important is not who is right—whether I am right or whether those are right who say a guru is necessary—but to find out why you need a guru is important. Gurus exist for exploitation of various kinds, but that is irrelevant. It gives you satisfaction if someone tells you how you are progressing. But to find out why you need a guru—there lies the key. Another can point out the way, but you have to do all the work, even if you have a guru. Because you do not want to face that, you shift the responsibility to the guru. The guru becomes useless when there is a particle of self-knowledge. No guru, no book or scripture can give you self-knowledge. It comes when you are aware of yourself in relationship. To be is to be related; not to understand relationship is misery, strife. Not to be aware of your relationship to property is one of the causes of confusion. If you do not know your right relationship to property, there is bound to be conflict, which increases the conflict in society. If you do not understand the relationship between you and your wife, between you and your child, how can another resolve the conflict arising out of that relationship? Similarly with ideas, beliefs, and so on. Being confused in your relationship with people, with property, with ideas, you seek a guru. If he is a real guru, he will tell you to understand yourself. You are the source of all misunderstanding and confusion, and you can resolve that conflict only when you understand yourself in relationship.

You cannot find truth through anybody else. How can you? Surely, truth is not something static; it has no fixed abode; it is not an end, a goal. On the contrary, it is living, dynamic, alert, alive. How can it be an end? If truth is a fixed point, it is no longer truth; it is then a mere opinion. Sir, truth is the unknown, and a mind that is seeking truth will never find it. For mind is made up of the known; it is the result of the past, the outcome of time—which you can observe for yourself. Mind is the instrument of the known; hence it cannot find the unknown; it can only move from the known to the known. When the mind seeks truth, the truth it has read about in books, that “truth” is self-projected, for then the mind is merely in pursuit of the known, a more satisfactory known than the previous one. When the mind seeks truth, it is seeking its own self-projection, not truth. After all, an ideal is self-projected; it is fictitious, unreal. What is real is what is, not the opposite. But a mind that is seeking reality, seeking God, is seeking the known. When you think of God, your God is the projection of your own thought, the result of social influences. You can think only of the known; you cannot think of the unknown, you cannot concentrate on truth. The moment you think of the unknown, it is merely the self-projected known. So, God or truth cannot be thought about. If you think about it, it is not truth. Truth cannot be sought—it comes to you. You can go only after what is known. When the mind is not tortured by the known, by the effects of the known, then only can truth reveal itself. Truth is in every leaf, in every tear; it is to be known from moment to moment. No one can lead you to truth, and if anyone leads you, it can only be to the known.

Truth can only come to the mind that is empty of the known. It comes in a state in which the known is absent, not functioning. The mind is the warehouse of the known, the residue of the known; and for the mind to be in that state in which the unknown comes into being, it must be aware of itself, of its previous experiences, the conscious as well as the unconscious, of its responses, reactions, and structure. When there is complete self-knowledge, then there is the ending of the known, then mind is completely empty of the known. It is only then that truth can come to you uninvited. Truth does not belong to you or to me. You cannot worship it. The moment it is known, it is unreal. The symbol is not real, the image is not real, but when there is the understanding of self, the cessation of self, then eternity comes into being.

Question: In order to have peace of mind, must I not learn to control my thoughts?

KRISHNAMURTI: To understand this question properly, we must go into it deeply, and that requires close attention. I hope you are not too tired to follow it.

My mind wanders. Why? I want to think about a picture, a phrase, an idea, an image, and in thinking about it, I see that my mind has gone off to the railway or to something that happened yesterday. The first thought has gone, and another has taken its place. Therefore I examine every thought that arises. That is intelligent, isn’t it? But you make an effort to fix your thought on something. Why should you fix it? If you are interested in the thought that comes, then it gives you its significance. The wandering is not distraction—do not give it a name. Follow the wandering, the distraction; find out why the mind has wandered; pursue it, go into it fully. When the distraction is completely understood, then that particular distraction is gone. When another comes, pursue it also. Mind is made up of innumerable demands and longings, and when it understands them, it is capable of an awareness which is not exclusive. Concentration is exclusiveness; it is resistance against something. Such concentration is like putting on blinkers—it is obviously useless, it does not lead to reality. When a child is interested in a toy, there is no distraction.

Comment from the audience: But that is momentary.

KRISHNAMURTI: What do you mean? Do you want a sustained wall to hold you in? Are you a human being or a machine, to be limited, circumscribed? All concentration is exclusive. In that concentrated exclusion, nothing can penetrate your desire to be something. So concentration, which so many practice, is the denial of real meditation. Meditation is the beginning of self-knowledge, and without self-knowledge, you cannot meditate. Without self-knowledge, your meditation is valueless; it is merely a romantic escape. So, concentration, which is a process of exclusion, of resistance, cannot open the door to that state of mind in which there is no resistance. If you resist your child, you do not understand him. You must be open to all his vagaries, every one of his moods. Likewise, to understand yourself, you must be alive to every movement of the mind, every thought that arises. Every thought that comes implies some interest—do not call it distraction and condemn it; pursue it completely, fully. You want to concentrate on what is being said, and your mind wanders off to what a friend said last evening. This conflict you call distraction. So you say, “Help me to learn concentration, to fix my mind on one thing.” But if you understand what causes distraction, then there is no necessity to try to concentrate—whatever you do is concentration. So the problem is not the wandering away but why the mind wanders. When the mind is wandering away from what is being said, then you are not interested in what is being said. If you are interested, you are not distracted. You think you ought to be interested in a picture, an idea, a lecture, but your interest is not in it, so the mind goes off all over the place. Why should you not acknowledge that you are not interested and let the mind wander? When you are not interested, it is a waste of effort to fix the mind, which merely creates a conflict between what you think you should be and the actual. It is like a motor car moving with the brakes applied. Such concentration is futile. It is exclusion, a pushing away. Why not acknowledge the distraction first? That is a fact. When the mind becomes quiet, when all the problems are resolved, it is like a pool with still waters in which you can see clearly. It is not quiet when it is caught up in the net of problems, for then you resort to suppression. When the mind follows and understands every thought, there is no distraction, and then it is quiet. Only in freedom can the mind be silent. When the mind is silent, not only the upper part, but fully, when it is free from all values, from the pursuit of its own projections, then there is no distraction—and only then reality comes into being.

November 20, 1949

Second Talk in Rajahmundry

It is very obvious that all problems require, not an answer, a conclusion, but the understanding of the problem itself. For the answer, the solution to the problem, is in the problem, and to understand the problem, whatever it is—personal or social, intimate or general—a certain quietness, a certain quality of unidentification with the problem is essential. That is, we see in the world at the present time great conflicts going on—ideological conflicts, the confusion and struggle of conflicting ideas, ultimately leading to war—and through it all, we want peace. Because, obviously, without peace one cannot create individually, which requires a certain quietness, a sense of undisturbed existence. To live quietly, peacefully, is essential in order to create, to think anew about any problem.

Now, what is the major factor that brings about this lack of peace within and without? That is our problem. We have innumerable problems of various types, and to resolve them, there must be a field of quietness, a sense of patient observation, a silent approach; and that is essential to the resolution of any problem. What is the thing which prevents that peace, that silent observation of what is? It seems to me that before we begin to talk of peace, we ought to understand the state of contradiction because that is the disturbing factor which hinders peace. We see contradiction in us and about us, and as I have tried to explain, what we are, the world is. Whatever our ambitions, our pursuits, our aims, it is upon them that we base the structure of society. So, because we are in contradiction, there is lack of peace in us and, therefore, outside of us. There is in us a constant state of denial and assertion—what we want to be and what we are. The state of contradiction creates conflict, and this conflict does not bring about peace—which is a simple, obvious fact. This inward contradiction should not be translated into some kind of philosophical dualism because that is a very easy escape. That is, by saying that contradiction is a state of dualism, we think we have solved it—which is obviously a mere convention, a contributory escape from actuality.

Now, what do we mean by conflict, by contradiction? Why is there a contradiction in us? You understand what I mean by contradiction—this constant struggle to be something apart from what I am. I am this, and I want to be that. This contradiction in us is a fact, not a metaphysical dualism, which we need not discuss. Metaphysics has no significance in understanding what is. We may discuss, say, dualism—what it is, if it exists, and so on—but of what value is it if we don’t know that there is contradiction in us, opposing desires, opposing interests, opposing pursuits? That is, I want to be good, and I am not able to be. This contradiction, this opposition in us must be understood because it creates conflict, and in conflict, in struggle, we cannot create individually. Let us be clear on the state we are in. There is contradiction, so there must be struggle, and struggle is destruction, waste. In that state, we can produce nothing but antagonism, strife, more bitterness and sorrow. If we can understand this fully and hence be free of contradiction, then there can be inward peace, which will bring understanding of each other.

So, the problem is this. Seeing that conflict is destructive, wasteful, why is it that in each of us there is contradiction? To understand that, we must go a little further. Why is there the sense of opposing desires? I do not know if we are aware of it in ourselves—this contradiction, this sense of wanting and not wanting, remembering something and trying to forget it and face something new. Just watch it. It is very simple and very normal. It is not something extraordinary. The actual fact is: there is contradiction. Then why does this contradiction arise? Is it not important to understand this? Because, if there were no contradiction, there would be no conflict, there would be no struggle; then what is could be understood without bringing into it an opposing element which creates conflict. So, our question is, is it not, why is there this contradiction and hence this struggle which is waste and destruction? What do we mean by contradiction? Does it not imply an impermanent state which is being opposed by another impermanent state? That is, I think I have a permanent desire. I posit in myself a permanent desire, and another desire arises which contradicts it, and this contradiction brings about conflict, which is waste. That is, there is a constant denial of one desire by another desire, one pursuit overcoming another pursuit. Now, is there such a thing as a permanent desire? Surely, all desire is impermanent—not metaphysically, but actually. Don’t translate this into something metaphysical and think you have understood it. Actually, all desire is impermanent. I want a job. That is, I look to a certain job as a means of happiness, and when I get it, I am dissatisfied. I want to become the manager, then the owner, and so on and on, not only in this world, but in the so-called spiritual world—the teacher becoming the principal, the priest becoming the bishop, the pupil becoming the Master.

So, this constant becoming, arriving at one state after another, brings about contradiction, does it not? Therefore, why not look at life, not as one permanent desire, but as a series of fleeting desires always in opposition to each other? Hence the mind need not be in a state of contradiction. If I regard life, not as a permanent desire, but as a series of temporary desires that are constantly changing, then there is no contradiction. I do not know if I am explaining myself clearly, because it is important to realize that wherever there is contradiction there is conflict, and conflict is unproductive, wasteful, whether it is a quarrel between two people or a struggle within; like war, it is utterly destructive.

So, contradiction arises only when the mind has a fixed point of desire, that is, when the mind does not regard all desire as moving, transient, but seizes upon one desire and makes that into a permanency—only then, when other desires arise, is there contradiction. But all desires are in constant movement; there is no fixation of desire. There is no fixed point in desire, but the mind establishes a fixed point because it treats everything as a means to arrive, to gain; and there must be contradiction, conflict, as long as one is arriving. I do not know if you see that point.

It is important to see, first of all, that conflict is essentially destructive, whether it is the communal conflict, the conflict between nations, between ideas, or the conflict within the individual. It is unproductive, and that struggle is utilized, exploited by the priests, by the politicians. If we realize this, actually see that struggle is destructive, then we have to find out how to bring about the cessation of struggle and must therefore inquire into contradiction; and contradiction always implies the desire to become, to gain, the desire to arrive—which after all is what we mean by the so-called search for truth. That is, you want to arrive, you want to succeed, you want to find an ultimate God or truth which will be your permanent satisfaction. Therefore, you are not seeking truth, you are not seeking God. You are seeking lasting gratification, and that gratification you clothe with an idea, a respectable-sounding words such as God, truth; but actually you are each one seeking gratification, and you place that gratification, that satisfaction, at the highest point, calling it God, and the lowest point, drink. As long as the mind is seeking gratification, there is not much difference between God and drink. Socially, drink may be bad, but the inward desire for gratification, for gain, is even more harmful, is it not? If you really want to find truth, you must be extremely honest, not merely at the verbal level, but altogether; you must be extraordinarily clear, and you cannot be clear if you are unwilling to face facts. That is what we are attempting to do at these meetings—to see clearly for ourselves what is. If you do not want to see, you can walk away, but if you want to find truth, you must be extraordinarily and scrupulously clear. Therefore, a man who wants to understand reality must obviously understand this whole process of gratification—gratification not only in the literal sense, but in the more psychological sense. As long as the mind is fixed as a “permanent” center, identified with an idea, with a belief, there must be contradiction in life, and that contradiction breeds antagonism, confusion, struggle, which means there can be no peace. So, merely to force the mind to be peaceful is utterly useless because a mind that is disciplined, forced, compelled to be peaceful is not at peace. That which is made peaceful is not peaceful. You can impose your will, your authority on a child to make him peaceful, but that child is not peaceful. To be peaceful is quite a different thing.

So, to understand this whole process of existence in which there is constant struggle, pain, constant disagreement, constant frustration, we must understand the process of the mind, and this understanding of the process of the mind is self-knowledge. After all, if I do not know how to think, what basis have I to think rightly? I must know myself. In knowing myself, there comes quietness, there comes freedom, and in that freedom there is discovery of what is truth—not truth at an abstract level, but in every incident of life, in my words, in my gestures, in the way I talk to my servant. Truth is to be found in the fears, in the sorrows, in the frustrations of daily living because that is the world we live in, the world of turmoil, the world of misery. If we do not understand that, merely to understand some abstract reality is an escape, which leads to further misery. So, what is important is to understand oneself, and understanding oneself is not apart from the world because the world is where you are—it is not miles away; the world is the community in which you live, your environmental influences, the society which you have created—all that is the world; and in that world, unless you understand yourself, there can be no radical transformation, no revolution, and hence no individual creativeness. Don’t be frightened of that word revolution. It is really a marvelous word with tremendous significance if you know what it means. But most of us do not want change; most of us resist change; we would like a modified continuity of what is, which is called revolution—but that is not revolution. Revolution can come into being—and it is essential for such a revolution to take place—only when you as an individual understand yourself in relation to society and therefore transform yourself; and such a revolution is not momentary, but constant.

So, life is a series of contradictions, and without understanding those contradictions, there can be no peace. It is essential to have peace, to have physical security, in order to live, to create. But everything we do contradicts. We want peace, and all our actions produce war. We want no communal strife, and yet that hope is denied. So, until we understand this process of contradiction in ourselves, there can be no peace, and therefore no new culture, no new state; and to understand that contradiction, we must face ourselves, not theoretically, but as we are, not with previous conclusions, with quotations from the Bhagavad-Gita, from Shankara, and so on. We must take ourselves as we really are, the pleasant as well as the unpleasant, which requires the capability of looking at exactly what is; and we cannot understand what is if we condemn, if we identify, if we justify. We must look at ourselves as we would look at that man walking on the road, and that requires constant awareness—awareness, not at some extraordinary level, but awareness of what we are, of our speech, our responses, our relationship to property, to poor people, to the beggar, to the scholar, and so on. Awareness must begin at that level, because to go far, one must begin near, but most of us are unwilling to begin near. It is much easier—at least we think it is much easier—to begin far away, which is an escape from the near. We all have ideals. We are experts at escape, and that is the curse of these escapist religions. To go far, one must begin near. This does not require some extraordinary renunciation but a state of high sensitivity because that which is highly sensitive is receptive, and only in that state of sensitivity can there be a reception of truth—which is not for the dull, the sluggard, the unaware. He can never find truth. But the man who begins near, who is aware of his gesture, of his talk, the manner of his eating, the manner of his speech, the ways of his behavior—for him there is a possibility of going very extensively, very widely into the causes of conflict. You cannot climb high if you do not begin low, but you do not want to begin low, you do not want to be simple, you do not want to be humble. Humility is humor, and without humor you cannot go far. But humor is not a thing which you can cultivate. So, a man who would really seek, who would know what truth is, or who would be open to truth must begin very near; he must sensitize himself through awareness so that his mind is polished, clear, and simple. Such a mind is not pursuing its own desires; it does not worship a homemade ideal. Only then can there be peace, for such a mind discovers that which is immeasurable.

Question: Why don’t you feed the poor instead of talking?

KRISHNAMURTI: It is essential to be critically aware, but not to pass judgment, because the moment you pass judgment, you have already concluded. You are not critically aware. The moment you come to a conclusion, your critical capacity is dead. Now, the questioner implies that he is feeding the poor, and I am not. I wonder if the questioner is feeding the poor! So, put to yourself this question, “Are you feeding the poor?” I am trying to inquire into the mentality of the questioner. Either he is criticizing to find out and therefore is at perfect liberty to criticize, to inquire, or he is criticizing with a conclusion and therefore is no longer critical, is merely imposing his conclusion; or, if the questioner is feeding the poor, then his question is justified. But, are you feeding the poor? Are you at all aware of the poor? On the average, people in India die at 27; in America and New Zealand it is 64 to 67. If you were aware of the poor, this state of things would not go on in India.

Now, the questioner wants to know why I am talking. I will tell you. To feed the poor, you must have complete revolution—not a superficial revolution of the left or of the right, but a radical revolution, and you can have radical revolution only when ideas have ceased. A revolution based on an idea is not a revolution because an idea is merely the reaction to a particular conditioning, and action based on a conditioning is not productive of fundamental change. So, I am talking to produce not mere superficial change but fundamental change. This is not a matter of inventing new ideas. It is only when you and I are free of ideas, whether of the left or of the right, that we can produce a radical revolution, inwardly and so outwardly. Then there is no question of rich and poor. Then there is human dignity, the right to work, opportunity and happiness for each one. Then there is no man with too much who must feed those with too little. There is no class difference. This is not a mere idea; it is not a utopia. It is an actuality when this radical revolution is inwardly taking place, when in each one of us there is fundamental change. Then there will be no class, no nationalities, no wars, no destructive separatism, and that can come about only when there is love in your heart. Real revolution can come only when there is love, not otherwise. Love is the only flame without smoke; but unfortunately we have filled our hearts with the things of the mind, and therefore our hearts are empty and our minds are full. When you fill the heart with thoughts, then love is merely an idea. Love is not an idea, but if you think about love, it is not love—it is merely a projection of thought. To cleanse the mind, there must be fullness of heart, but the heart must be emptied of the mind before it can be full, and that is a tremendous revolution. All other revolutions are merely the continuation of a modified state.

Sir, when you love somebody—not the way we love people, which is only thinking about them—when you love people completely, wholly, then there is neither rich nor poor. Then you are not conscious of yourselves. Then there is that flame in which there is no smoke of jealousy, envy, greed, sensation. It is only such a revolution that can feed the world—and it is up to you, not to me. But most of us have grown accustomed to listening to talks because we live in words. Words have become important because we are newspaper readers; we listen habitually to political talks which are full of words without much meaning. So we are fed on words, we survive on words; and most of you are listening to these talks merely on the verbal level, and therefore there is no real revolution in you. But it is up to you to bring about that revolution, not the revolution of blood, which is a modified continuity which we miscall revolution, but that revolution which comes into being when the mind is no longer filling the heart, when thought is no longer taking the place of affection, compassion. But you cannot have love when the mind is predominant. Most of you are not cultured but merely well-read, and you live by what you have learned. Such knowledge does not bring about revolution, does not bring about transformation. What brings about transformation is understanding everyday conflicts, everyday relationships. When the heart is empty of the things of the mind, then only does that flame of reality come. But one must be capable of receiving it, and to receive it, one cannot have a conclusion based on knowledge and determination. Such a mind, being peaceful, not bound by ideas, is capable of receiving that which is infinite, and therefore it creates revolution—not merely to feed the poor or to give them employment or to give power to those who have no power, but it will be a different world of different value, not based on monetary satisfaction.

So, words don’t feed hungry men. Words to me are not important; I am using words merely as a means of communication. We can use any word as long as we understand each other; and I am not giving you ideas, I am not feeding you words. I am talking so that you can see clearly for yourselves that which you are, and from that perception you can act clearly and definitely and purposefully. Only then is there a possibility of cooperative action. Talking merely to amuse ourselves is of no value, but talking to understand ourselves and thus bring about transformation is essential.

Question: In your talks in 1944, the following question was put to you: “You are in a happy position. All your needs are met. We have to earn money for ourselves, our wives and families. We have to attend to the world. How can you understand us and help us?” That is the question.

KRISHNAMURTI: I tried to answer the question; I did not evade it, but perhaps I may have put it in a way that appears to the questioner as evasion. Life is not a thing to be settled with yes or no; life is complicated; it has no such permanent conclusion. It is like your wanting to know if there is or is not reincarnation. We must go into it. In discussing it, you think I am evading because your mind is fixed on one thing, either “there is” or “there is not.” So, from your point of view, it is obviously an evasion, but if you look into it a little more clearly, you will see that it is not evasion.

Now, the questioner wants to know—since my needs are provided by others, how can I understand those who are struggling with life to provide for their families and themselves? What is the implication of this question? That you are privileged and we are not, and how can the privileged class understand the unprivileged? So, the question is: Can the privileged person understand the unprivileged?

First of all, am I privileged? I am privileged only when I accept position, authority, power, the prestige of asserting myself to be somebody—which I have never done because to be somebody is highly immoral, unethical, and unspiritual. To be somebody denies reality, and it is only the one who is somebody that is privileged. He exploits and denies, but I am not in that position. I go about speaking, and for that I am paid as you are paid for your job, and I am treated exactly on that level. My needs are not very great because I do not believe in great needs. A man who is burdened with many possessions is thoughtless, but the man who avoids possessions and the man who is identified with a few possessions are equally thoughtless. So, I earn my living as you earn yours. I speak, and I am asked to go to different parts of the world. Those who ask me to go, pay for it. If they do not ask, if I do not talk, it is all right. For me, talking is not a means of self-expression or exploitation. I do not find gratification in it; it is not a means of exploiting you or getting your money because I do not want you to do any charity, to believe this or not to believe that. I am talking merely to help you see that which you are, to be clear in yourself. For in clarity there is happiness; in understanding there is enlightenment. There is happiness in discussing together, for in that discussion we can see ourselves as we are. This relationship may act as a mirror, for all relationship is a mirror in which you and I discover ourselves.